Introduction

In the last 30 years, Local Governments (LGs) all over Europe experienced an intense season of institutional change of unprecedented width and intensity. This change caused increasing academic interest (Kersting and Vetter, Reference Kersting and Vetter2003; Baldersheim and Rose, Reference Baldersheim and Rose2010). It indeed occurred not only through Constitutional or territorial reforms but also through other provisions that, albeit indirectly and incrementally, strongly impacted LGs. These indirect provisions – here labeled as oblique – are all but secondary in affecting the overall institutional change and in altering the level of autonomy of local authorities. This paper focuses on this other type of change and shows the remarkable extent to which oblique-change and oblique-provisions (OPs) do indeed impact the overall LG institutional change, and how the debate on local autonomy could be fruitfully nurtured by adopting this uncommon perspective. Moreover, it argues that bradyseismic adjustments provoked by oblique-change may turn out in an equally profound change of the LG asset, as that induced by a major reform's earthquake.

Mining from different strands of literature, this article explores Local Government change through the lens of the oblique-change and shows its relevance by looking at its frequency, magnitude, and direction trying to systematically account for it around the years of the global crisis (Silva and Bucek, Reference Silva and Bucek2014; Lippi and Tsekos, Reference Lippi and Tsekos2019).

Italy has been chosen as a pilot case starting from the empirical observation that numerous changes occurred in its LG, and that those changes have been discussed in the literature as fragmented (Dente, Reference Dente and Hesse1991, Reference Dente1997), scattered and complex (Baldini and Baldi, Reference Baldini and Baldi2014). The Italian case provides an extraordinary richness of evidence, which allows an accurate analysis. However, oblique-change as an essential driver of institutional change is not peculiar to this country-case, so that the Italian findings may serve as a benchmark in a broader comparative perspective.

A Before/After assessment will be performed, where the turning point is represented by the global crisis years and by 2012 as its climax. In order to put the Italian LG case in context and to account for its variations, we rely on the (adapted) main scopes of the Local Authority Index (LAI) (Ladner et al., Reference Ladner, Keuffer, Baldersheim, Hlepas, Swianiewicz, Steyvers and Navarro2019) to cross them with the four traditional dimensions in the LG studies, namely the legal, organizational, functional and political dimensions (Page and Goldsmith, Reference Page and Goldsmith1987; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks, Schakel, Osterkatz, Niedzwiecki and Shair-Rosenfield2016). The Before/After analysis will allow detecting the primary shifts for each of the dimensions, to thus argue on the frequency, magnitude, intensity, and direction of these shifts, and to finally assess LG change in Italy.

Section ‘Adopting oblique-change to approach institutional change in LG’ presents the different strands of literature that inspired our reasoning, while section ‘Definition, analytical strategy, and measurements’ proposes the label of oblique-change and explains the methodological approach employed. Sections ‘Evidence before-2012’ and ‘Evidence after-2012’ picture the before- and after-2012 period and relevant evidence, respectively. Section ‘Discussion’ presents the overall assessment of LG changes and discusses the findings. Section ‘Conclusion’ proposes some final remarks.

Adopting oblique-change to approach institutional change in LG

Scholarly literature on institutional change is rich and multifaceted. True, institutional studies mostly focus on the State level and Constitutional changes and/or radical institutional policy changes (Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010), but the idea of a change due to ‘minor’ events has also been scrutinized (Thoenig, Reference Thoenig, Peters and Pierre2003). Starting from this idea, this paper relies on several different strands of literature that account for an evolutionary, incremental, and indirect approach to institutional change and that, directly or indirectly, refer to the broad category of what we label here oblique-change. In particular, those studies on evolutionary change in institutional reforms, as well as the institutionalist literature on incremental change, provide some exciting insights in this regard.

As for the first strand, Behnke and Benz (Reference Behnke and Benz2009) distinguished between reforms and evolutions: while reforms are explicit and defined as an alteration of the written text of the Constitution, evolution is often implicit and formally residual, rooted in minor acts. Evolution affects the change that does not pertain to the written text, altering meaning and practices without changing the wording (Reference Behnke and Benz2009, 217) of the official legal frame. This kind of change can re-stabilize the previous arrangement by micro-alterations such as limited legislation, intergovernmental agreements, or judicial sentencing. Analogously, Kropp and Behnke (Reference Kropp and Behnke2016) introduced the concept of zigzagging change concerning the German federalism. This change concerns the institutional incongruity intrinsically triggered by the game power between federal and subnational entities, thus enhancing provisions that may alter in a different (and sometimes simultaneous) way the autonomy of the local government. The incongruent nature of intergovernmental relations, also described by Agranoff (Reference Agranoff1990), sheds light on the continuous oscillating movements induced by long-lasting adjustments between central and local government. Although it has been recognized as a typical feature of the federalist countries, this zigzagging change has been also observed in unitary and regionalized states. Moreover, Malsch and Gendron (Reference Malsch and Gendron2013), following Bourdieu's approach, emphasized the construction of power relations based on intertwined macro- and micro-dynamics, while other scholars introduced the idea of micro-foundations of change, to be detected in the interaction between micro- and macro-institutions (Harrington, Reference Harrington2015).

As for the second strand, oscillating and gradual adjustments have been explored since the seminal studies of Charles Lindblom. In recent decades, scholars have indeed extensively focused on the relevance of these incremental adjustments (DiMaggio and Powell, Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983; Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010). Groundbreaking patterns of change like Neo-liberalism or New Public Management worked as ruptures, but after their initial introduction, they opened up the path for ‘incremental change with transformative results’ (Streeck and Thelen, Reference Streeck and Thelen2005: 9). This assumption implies that institutional change occurs ‘as a result of the normal, everyday implementation, and enactment of an institution’ (ibidem: 11). Indeed, if excluding some punctual and rare turning points, change usually occurs by reproduction and adaptation (Jepperson, Reference Jepperson, DiMaggio and Powell1991: 150). As claimed by Mahoney and Thelen (Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010: 8) ‘where institutions represent compromises or relatively durable though still contested settlements based on specific coalitional dynamics, they are always vulnerable to shifts’. Recently, Hoppe (Reference Hoppe2017: 228–230) interestingly combined the above-recalled concept of evolution and Lindblom's concept of disjointed incrementalism by capturing the relevance of stepwise sequences of disentanglement and re-entanglement of institutional arrangements – conceived as a series of incoherent and piecemeal muddling-throughs, made of extension and retrenchment. He stressed the relevance of incrementalism as a type of institutional change showing the limits and potentialities of Lindblom's micro-adjustments theory. Hoppe argues that non-incremental change does not exclude neither the existence nor the relevance of incremental change; as well macro-change does not hinder the relevance of micro-change. Both micro and macro thus co-exist and must be held together when aiming at grasping the complexity of interactions between actors and institutions. This is particularly true when looking at territorial institutions and the relationships between different levels of government or different territorial spaces or units.

The theoretical relevance of evolutionary and incremental change can also be found in the recent literature on LG as well as in that strand exploring the influence of the global crisis on its arrangements.

LG studies have in fact tackled the issue of the evolution of institutional arrangements paying attention to trajectories and indirect modifications. The modifying trajectories do not automatically imply a change of the pattern, but instead a change in the pattern (Bolgherini et al., Reference Bolgherini, Di Giulio and Lippi2018b). In the last three decades, the variability and the complexity of Local Government in the European context have been scrutinized by mostly looking at regularities and patterns across national differences (Mouritzen and Svara, Reference Mouritzen and Svara2002; Kersting and Vetter, Reference Kersting and Vetter2003; Kuhlmann and Bouckaert, Reference Kuhlmann and Bouckaert2016), and a number of taxonomies have been proposed (Steyvers, Reference Steyvers2019). If it is true that LGs are a relatively stable phenomenon that can be scrutinized through dimensions and models conceived as permanent, at the same time, they are also subject to continuous extensions or retrenchments of their autonomy.

Recently, trajectories and indirect change, incrementalism and evolutionary change, as well as indirect transformations, returned under the spotlight (Kuhlmann, Reference Kuhlmann2010; Kuhlmann and Bouckaert, Reference Kuhlmann and Bouckaert2016). During and after the global crisis in fact, LG studies focused on reforms (Schwab et al., Reference Schwab, Bouckaert and Kuhlmann2017; Kuhlmann and Wollmann, Reference Kuhlmann and Wollmann2019), devoting increased attention to the transformation induced by (often external) pressures: scholars examined the change of the consolidated patterns rather than the features of these patterns, as it was in the past. Nonetheless, the focus remained that of the direct and more visible change through significant LG reforms. A critical turn occurred with the global crisis' years. The effects of the austerity policies and the fiscal measures on local government have been explored (Hlepas and Getimis, Reference Hlepas and Getimis2010; Silva and Bucek, Reference Silva and Bucek2014; Di Mascio and Natalini, Reference Di Mascio and Natalini2015; Kuhlmann and Bouckaert, Reference Kuhlmann and Bouckaert2016; Lippi and Tsekos, Reference Lippi and Tsekos2019) revealing the changing nature of LG when undergoing severe retrenchments due to fiscal constraints (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Pierre and Randma-Liiv2011) and downsizing of their autonomy due to recentralization attempts by the part of the central States after decades of decentralization and empowerment of the local authorities (Bolgherini, Reference Bolgherini2016; Heinelt et al., Reference Heinelt, Hlepas, Kuhlmann, Swianiewicz and Heinelt2018). If it holds true that austerity measures have been particularly harsh in Southern Europe and had an unprecedented impact on LGs, the literature on this topic has also clearly shown that change happened more through indirect and collateral provisions (e.g., through across-the-board measures, or fiscal austerity instruments like salary- or hiring-freezing, limits to borrowing, etc.) (Overmans and Noordegraaf, Reference Overmans and Noordegraaf2014; Kickert and Randma-Liiv, Reference Kickert and Randma-Liiv2015) rather than through direct and explicit reforms addressing the local level.

The years of the global crisis thus unprecedently brought to surface how this different type of change may be impacting and radical, and therefore how addressing it – both as such and across those particular years – might be a particularly fruitful path.

Definition, analytical strategy, and measurements

To this purpose, we propose the label of oblique-change, approached here as a significantly broad category summing up the above-recalled institutional change characterized by incrementalism, evolutionary modifications, and indirectness. Oblique-change has its opposite in straight-change, meaning directly, actively, and explicitly LG-focused reforms intentioned to alter the LG arrangement.

These labels recall Charles Lindblom's perspective of obliqueness as a form of interdependent coordination between the State and the market (Reference Lindblom1995: 686). This inter-dependency does not imply straightness and linearity, being State's coordination often indirect and non-linear. Instead authority, influence, and provisions for altering subordinated units (in the market world, as well as in the State) in democratic regimes, are usually, and mostly, performed by oblique means (Lindblom, Reference Lindblom1977: 26).

As well, they recall the classical Theodore Lowi's distinction between remote (here oblique) and immediate (here straight) coercion, where remoteness (obliqueness) occurs ‘if sanctions are absent, or if they are indirect’ (Reference Lowi1972: 299).

Straight-change is immediate and direct and, in our perspective, explicitly focused on LG, with expressed and claimed will of altering or reshaping some of its aspects. Straight-change can be thus enacted through all those provisions – here labeled as straight-provisions (SPs) – that explicitly address (and are aimed at) an LG change. SPs are usually, although not exclusively, Constitutional changes, statutory modifications of the institutional framework or the legal entitlements, significant and structural reforms – all those that in the institutional theory have been labeled as macro-change (Mahoney and Thelen, Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010: 7–11), for their expected ample magnitude.

Oblique-change has instead remote and indirect effects on LGs. It is, in fact, more mediated – being often intertwined with other provisions, reforms or decisions originating in other policy areas than LG; and it is often triggered by a policy window on a more general issue, which then turns out to be also linked with LG (such as the norms for ICTs in public administration, for hiring in public employment or for public bodies' fiscal rules). Oblique-change can indeed result from all those oblique-provisions – here labeled as OPs – not expressly oriented to rearrange LG, but that can nonetheless reshape some of its crucial aspects or affect its operative side and daily functioning. OPs may appear as evolutionary legislation, for example, provisions that can cumulatively reshape power, resources, and structure of the LG; as incremental provisions (e.g., all-in-one laws), which can be episodically revised, abolished, readjusted and restored through specific directives, technicalities guidelines (e.g., cap to expenditures), organizational regulation, instructions or prescriptions, judgments or acts by Courts, Ministries, Agencies and central authorities; or as indirect provisions, namely acts, decrees, reforms or amendments expressly oriented to modify other policy areas or aspects of the public administration (e.g., finance controlling or turn-over stop in hiring, or modification of public service management or delivery requisites).

From a legal point of view, OPs are often, although not exclusively, secondary legislation but, in our perspective, all but minor, since they may produce equally radical change and substantially alter LG's autonomy as a major straight reform issued by primary legislation. Moreover, it is important to stress that what distinguishes SP from OP in our perspective is not the legal status or hierarchy of a provision, but rather the salience and type of induced change. That means that the same type of provision (i.e., a legislative decree) may be an OP in one case, and an SP in another: what differs is the nature of the change and the ways it affects LG autonomy.

To assess the degree of oblique-change in local government, an in-depth exploration of a case-study seems to be the most appropriate strategy: a careful use of the case-study design (Jensen and Rodgers, Reference Jensen and Rodgers2001; Pennings et al., Reference Pennings, Keman and Kleinnijenhuis2006; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Reynolds and Mycoff2019) would serve to make the single-country more relevant, and provide a bridge for comparative insights (Lees, Reference Lees2006).

Italy is a particularly fitting case to provide this assessment for a series of reasons. Among the European countries, Italy has been traditionally analyzed as a peculiar case marked by institutional fragmentation and specific center-periphery relations (Dente, Reference Dente and Hesse1991, Reference Dente1997). An unequaled density of reforms with ambiguous results have in time depicted a fragmented and continuous institutional change that led to a permanent state of vagueness and incompleteness (Bobbio, Reference Bobbio, Denters and Rose2005; Piattoni and Brunazzo, Reference Piattoni, Brunazzo, Frank Hendriks and Loughlin2010; Lippi, Reference Lippi2011). These considerations allow envisaging this country as a significant case of variegated institutional change. Second, having been permanently under reform since three decades, Italy is undoubtedly a ‘thick’ case as far as reforms, evolutions, and change are concerned, both in quantity (number of reforms and reform attempts) and in quality (being some of them of particularly high impact), let alone the variety (Baldini and Baldi, Reference Baldini and Baldi2014). Third, along the years, this country often displayed incomplete and scattered implementation of the reforms, flanked by a plethora of incremental, indirect, and piecemeal legislation, thus displaying a vast variety of trajectories, movements, and paths (Bolgherini et al., Reference Bolgherini, Di Giulio and Lippi2018b). Finally, while for federal countries, frequent incremental changes are embedded in the institutional asset (Benz and Broschek, Reference Benz and Broschek2013; Behnke and Kropp, Reference Behnke and Kropp2016; Benz, Reference Benz2016), for unitary States, it is less so. Italy, being a unitary regionalized state, is institutionally located between these two categories, thus providing an exciting intersection case. For all these reasons (time span, quantity, quality of reforms, variety of reform types and changes, as well as variety of sources for assessing that change), Italy is a suitable exploratory pilot case-study for investigating institutional change through oblique-change and OPs and for allowing to draw some conclusion on this phenomenon for future comparative perspectives.

The investigated time-span runs across 2012, which is considered a critical juncture in Italy as far as the austerity rhetoric (Citroni et al., Reference Citroni, Lippi, Profeti, Lippi and Tsekos2019) and the consequent reorganization measures (Bolgherini et al., Reference Bolgherini, Dallara and Profeti2019). The analysis will proceed through a Before/After comparison: the Before-2012 period will cover the 1990–2012 years, that is from the significant administrative and political reforms in the early 1990s until the global crisis juncture; the After-2012 period will instead cover the last years until today.

The Before/After analysis will be pursued by relying on the theoretical basis of two consolidated contributions in the LG studies.

The first is that originating from Page and Goldsmith (Reference Page and Goldsmith1987) and Page (Reference Page1991), who introduced three main features to categorize LG variability (functional, territorial, political), each capturing the variance of local government in Europe according to a different aspect. In the same line, more recently, other scholars looked at the degree of local authorities' autonomy (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks, Schakel, Osterkatz, Niedzwiecki and Shair-Rosenfield2016; Keuffer, Reference Keuffer2016; Ladner et al., Reference Ladner, Keuffer, Baldersheim, Hlepas, Swianiewicz, Steyvers and Navarro2019) through four analytical dimensions: the functional dimension, including tasks and financial resources; the legal dimension, that pertains to the constitutionally-granted rights, the political dimension, concerning intergovernmental relations (access, influence, supervision, and control) and the organizational dimension, focused on management and human resources.

The second is that of Ladner et al. (Reference Ladner, Keuffer, Baldersheim, Hlepas, Swianiewicz, Steyvers and Navarro2019). These authors, drawing from Hooghe et al. (Reference Hooghe, Marks, Schakel, Osterkatz, Niedzwiecki and Shair-Rosenfield2016), proposed a Local Autonomy Index, computed on two main principles (or scopes): Self-rule (i.e., to what extent an LG is independent of its relevant central authorities) and Shared-rule (i.e., to what extent LG may have a say in national policy-making), which currently represent an important instrument for assessing LG statics and dynamics.

We will proceed then by combining the four traditional dimensions (political, legal, administrative, organizational) with the two LAI scopes (self- and shared-rule). The two scopes will be explored in each of the four dimensions through their specific variables and will serve as a tool to capture the impact of OPs, and therefore of oblique-change in the two phases.

Operationally, for each scope, the LAI variables will be grouped into three main sub-dimensions. The original LAI index is formed by 11 variables. Self-rule comprises Institutional depth (ID), Policy scope (PS), Effective political discretion (EPD) (here grouped under the label Policy autonomy); Fiscal autonomy (FA), Financial transfer system (FTS), Financial self-reliance (FSR), Borrowing autonomy (BA) (summed up here under Fiscality); and Organizational autonomy (OA). Shared-rule comprises instead Legal protection (LP); Administrative supervision (AS); and Central or regional access (CRA).

In order to explore institutional change through oblique-change, a two-step analytical strategy has been pursued. In the first step, an overview of the main SP and OP for each dimension and scope will be sketched, as well as the first assessment on their impact on LG autonomy in terms of extension or retrenchment. Selected evidence – described in the following sections and relevant tables, and listed in detail in the Appendix – has been retrieved from State legislation, from official fiscal reports of the Ministry of Finance, and other official sources. In the second step, an assessment of the frequency, magnitude, intensity, and direction of oblique-change will be performed, in order to finally draw a picture on the impact of this under-explored form of change on the overall institutional change in local government.

Evidence before-2012

Until the 1990s, Italian LG had remained substantially unchanged or had been only partially modified (Bolgherini and Lippi, Reference Bolgherini, Lippi, Sadioglu and Dede2016: 267). Since 1990 however, it has been subject to significant modifications that added stepwise innovative elements (Brunazzo, Reference Brunazzo, Baldersheim and Rose2010; Bolgherini and Lippi, Reference Bolgherini, Lippi, Sadioglu and Dede2016) in a sort of never-ending wave of significant reforms and small provisions, each characterized by limited and negotiated changes (Bull and Rhodes, Reference Bull and Rhodes2007). This process started at the beginning of the 1990s, but it continued all along a quarter of a century. Some innovations have been abandoned and then restored, others continued to be steadily relevant in the public agenda.

Table 1 resumes the main evidence of this period along the four dimensions, and the LAI scopes and classifies the provisions as oblique (OP) or straight (SP). Moreover, it assesses their extensive (E) or retrenching (R) nature in terms of LG autonomy. Simply put, a provision is considered an extension if it does enlarge, on the relevant dimension and scope, the possibilities for local government to act, decide and work; or a retrenchment if instead, it shrinks them.

Table 1. Before-2012 period

Provisions classified per scope and dimension as: oblique (OP) or straight (S), implying an extension (E) or a retrenchment (R) of local autonomy.

Source: Authors' compilation.

The before-2012 period is marked at the legal level by several SPs: seven SPs out of the 10 of this period are on this dimension, including some relevant reforms aimed at empowering Local Authorities and Regions, through both Constitutional changes and many significant reform laws. Change mainly concerned Regions in terms of territorial governance and concurrent law-making power (nn.1, 8, and 12), and LG's fiscal autonomy (nn.3–6). The direct elections of mayors and province's president (1993), as well as that of the Regions' governors (1999), were also introduced (n.7), empowering local levels' executive bodies. OPs on the legal dimensions concerned new (EU-compliant) norms for local public services (LPSs) (n.9), a reform on the management of local health care system (n.2), and the role of prefectures (n.10–11) that became a supervision body for local autonomies.

On the other three dimensions, OPs were instead overwhelming (28 out of 33), mainly at the organizational (10) and functional (15) level.

On the first, several small and sectoral provisions affected LG mostly in its self-rule (organizational and policy autonomy): from the recruitment of managers, civil servants and clerks by the majors (nn.18–19, but also later in the opposite direction, nn.21–22), to general rules for public employment (n.21) and the establishment of performance assessment (n.13 and later n.25). The creation of a permanent conference between the State and the Regions (n.23) enhanced intergovernmental relations instead. On the functional dimension, very numerous OPs witness the development of policy autonomy (nn.26–29) or the reshaping of LPSs (nn.34–36) spanning the late 90s–early 2000s. Some stress the beginning of the global crisis instead, especially in terms of added financial and supervision controls and constraints in several self- and shared-rule aspects (nn.30–33, 40) or restrained organizational autonomy (nn.37–39). Following this, an increasing up- and trans-scaling trend occurred through OPs in many policy areas (Bobbio, Reference Bobbio, Denters and Rose2005; Lippi, Reference Lippi2011; Bolgherini and Dallara, Reference Bolgherini and Dallara2016).

A strongly legitimated (local) politics – due to the direct election of local executives (nn.42–43) and to the consolidation of political representation as partially independent from the national party system (n.41) (Baccetti, Reference Baccetti2008) – is conceivable as an oblique-effect on the political dimension.

Evidence after-2012

Two main sets of provisions mark the second period. The first, issued in the 2012–2014 biennium, comprises a territorial reform that straight impacted LGs, and several related austerity measures that obliquely hit them. The second set, issued around the 2015–2017 biennium, comprehends OPs that invested organizational aspects of local governments (e.g., with norms for hiring, public employment and administration, rules for personnel) on the one hand, and arrangements of LPSs (e.g., procurement rules, norms for corporatization, etc.) on the other hand.

The territorial institutional reform triggered in 2010 – and culminated with the Delrio Law in 2014 – introduced a major reshaping in the Italian LG. This law systematized and re-launched previous reforms (or attempts to) concerning territorial arrangement, which had started a decade before (Di Giulio and Profeti, Reference Di Giulio and Profeti2016) to consolidate two principles: the reduction of the costs of the political class, and the budget containment. The Delrio Law explicitly provided a framework for local government and regional decision-making: it delegated the regions to reshape their own multilevel sub-regional governance (Bolgherini et al., Reference Bolgherini, Lippi and Maset2016). In 2015, the Renzi government proposed a Constitutional reform that should integrate the Delrio Law with, along with other issues, a significant recentralization of legal powers in the hands of the State (Citroni et al., Reference Citroni, Di Giulio, Galanti, Lippi, Profeti, Kopric, Marcou and Wollmann2017). The Constitutional reform eventually failed through a rejection by a popular referendum in 2016, thus leaving the territorial issue to a stalemate and the differently – oriented and scattered-implemented choices of the single regions.

The political climate in that early post-2012 years was overall particularly intense and produced a series of significant consequences for LG. For instance, fiscality played a significant role, through three main approaches that brought to several obliquely-impacting provisions. A first strategy implied cheese-slicing-cutbacks that affected the public sector as a whole (Di Mascio and Natalini, Reference Di Mascio and Natalini2015). The second approach employed selected cutbacks explicitly focused on local public spending and specifically on social services. A third strategy pushed LGs to self-contain their spending through overall cuts to local policies and increasingly stiff budgets, thus inducing most municipalities either to look for alternative sources of funding or to self-reduce their public service delivery.

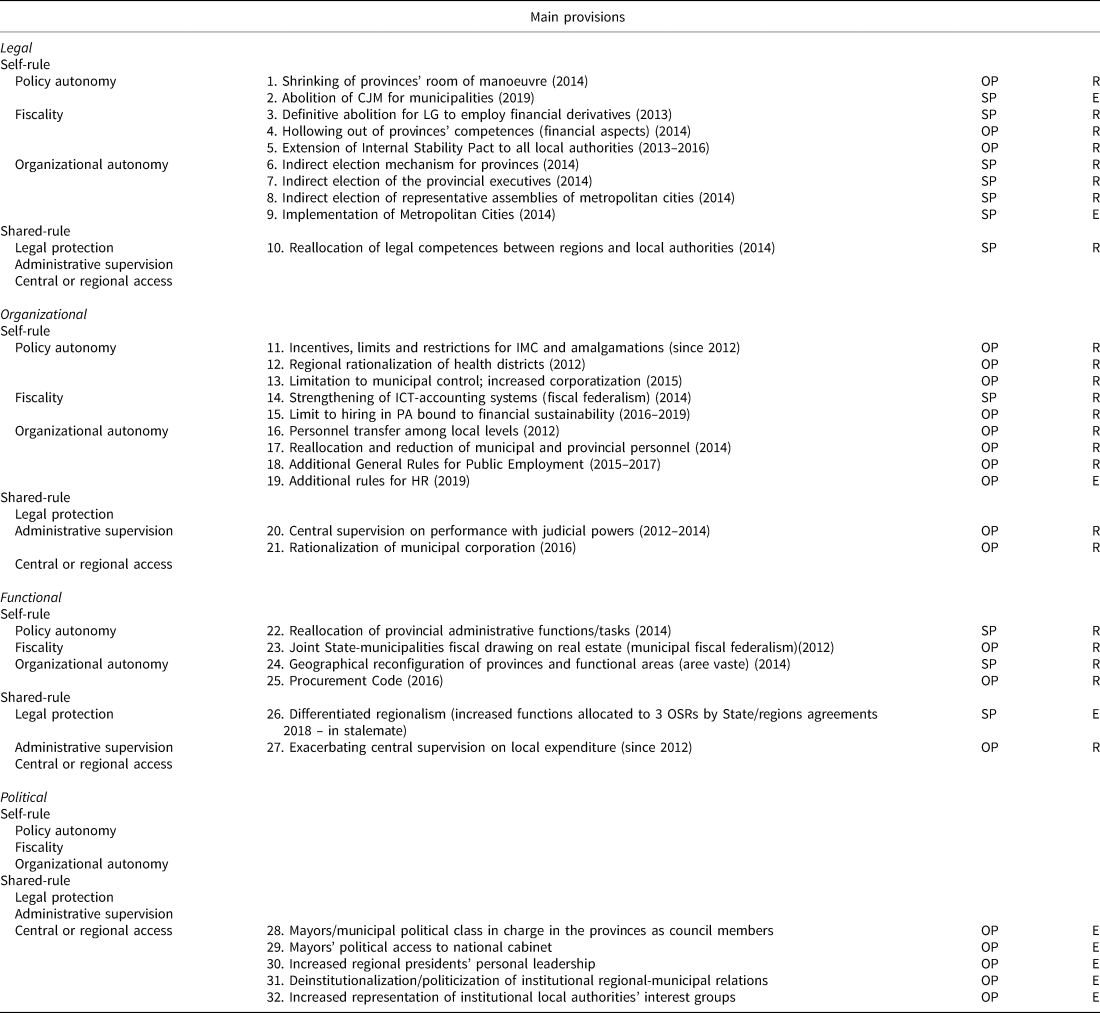

Table 2 displays in detail the provisions that materialize the features and approaches of the second period, as well as their extensive or retrenching nature in terms of local autonomy.

Table 2. After-2012 period

Provisions classified per scope and dimension as: oblique provisions (OP) or straight provisions (S), as extension (E) or retrenchment (R) of local autonomy.

Source: Authors' compilation.

Legal

In the legal dimension, the main provisions are linked to the above-mentioned territorial reform, finalized in the 2014 Delrio Law. Although the complementary Constitutional change that pointed toward a recentralization of competences in favor of the central State failed, the overall effects of this reform season highly and straight impacted LG. In 2012–2013, provinces' competences started to be questioned and then hollowed out through oblique austerity measures (nn.1, 4). In 2014, the Delrio Law (SP) transformed the provinces into indirectly-elected second-tiers of government (n.7) – thus also reducing the number of elected representatives and administrative personnel (n.6); implemented nine Metropolitan Cities in the biggest Italian cities (replacing their relevant provinces)(nn.8–9); and entitled the city of Rome with a special legal status. This law reshaped the framework of intergovernmental relations and outlined a different multilevel governance between the Regions and the Local Authorities. A gradual process of reallocation of legal power among State, Regions, Provinces, Metropolitan cities, and municipalities followed. However, this was enacted in each region with different timings, strategies, and designs (OP – n.10). The Compulsory joint management (CJM) for municipalities – introduced in 2010 as OP, then reinforced by the Delrio Law and then definitely canceled in 2019 by the Constitutional Court (Bolgherini et al., Reference Bolgherini, Casula and Marotta2018a) as SP (n.2) – is an example of the uncertainty that followed.

Overall, in the legal dimension, the prevalence of SPs (seven out of 11) is higher than that of the oblique ones (only three).

Organizational

Fragmented OPs are prevalent in this dimension (10 out of 11), ranging from policy autonomy aspects to organizational, administrative, and fiscal ones. Most of these provisions were introduced in a scattered and incremental way, and they were often pushed by austerity: reduction of personnel, freezing of retirements, strong constraints to hiring and turn-over (nn.15–19), rationalization of LPSs (nn.12–13, but also nn.20–22).

Concerning specifically LPSs, a stream of provisions incrementally tried to disentangle the ambiguous and overlapping legislation on provider–purchaser regulatory governance. Many of these regulatory provisions (OPs), aimed at rationalizing the blurred and redundant arrangements, were introduced to limit the municipal legal power and to establish financial constraints for them (Citroni et al., Reference Citroni, Lippi, Profeti, Wollmann, Marcou and Kopric2016). Increased supervision on the local performance and customer satisfaction was also introduced and assigned to a central agency equipped with judicial power (ANAC) (n.21, OP).

Finally, uncertain rules – deriving once again from the Delrio reform – invested municipalities and more or less openly pushed them to cooperate or to merge (n.11).

Functional

The Delrio Law in 2014 deeply impacted the previous territorial arrangement also in the functional dimension: it reallocated the administrative functions and tasks of the second-tier authorities (provinces) to other bodies (mainly to regions but also to Metropolitan cities and partly to municipal unions) (Di Giulio and Profeti, Reference Di Giulio and Profeti2016) (n.23, SP). Provinces should, however, have been replaced by functional areas (area vasta) (n.25, SP) – whose definition remains nonetheless blurred – thus leaving room to different strategies enacted by the Italian regions, according to their different attitudes, legacies, and approaches to innovation (Bolgherini et al., Reference Bolgherini, Lippi and Maset2016). A follow-up of the reform could have been the differentiated regionalism, another SP directed to LG that however has currently stuck in the agenda (n.27). Should the bilateral State/Regions agreements signed in 2018–2019 be concluded, some Italian ordinary status regions could be entitled with enlarged powers in some specific policy areas, thus further unbalancing the current assessment of the country.

New rules for funding local policies (e.g., the fiscal drawing on municipal real estate – n.24, OP), coupled with increased rigidity and central supervision on public expenditure (n.28), were established in rationalization and recentralization attempts: this further hindered and delayed the spending capacity of Italian LGs. The central government, in fact, reinforced its (already strong) supervision: municipal procedures and deadlines for approving the municipal budgets should align the State timeline, and local expenditure must be accounted for on a cash-flow basis instead of on the principle of State transfers. Moreover, also other OPs like the tight procurement code (n.26) limited LG's autonomy.

Political

Traditional studies (Page and Goldsmith, Reference Page and Goldsmith1987; Page, Reference Page1991; Goldsmith and Page, Reference Goldsmith and Page2010) consider Italy as an example of political localism, where local actors may have direct and powerful access to political resources and the national level. Between the territorial law in 2014 and the failed Constitutional reform in 2016, these traditional features seem to have even reinforced, thus displaying a particularly strong influence of the local-level politicians in the national arena as an oblique effect on LG.

Data gathered with the aim of testing if, in this phase, a different trend in the career paths of politicians could be detected, confirm the general trend of mixed career paths,Footnote 1 with no significant difference between the 1990–2010 period and the 2010–today. Notwithstanding these data, it is undeniable that, at least from a mass media point of view, local politicians in this last phase became prominent at the national level, thus reinforcing the political access' element (nn.29–31, OP). Former Prime Minister Matteo Renzi and former Minister Graziano Delrio, both former mayors in medium-large cities, stand out as the most emblematic examples (n.30).

Moreover, Local Authorities' interest groups like the Association of the municipalities (ANCI) or that of the metropolitan cities have increased their consultant influence and negotiating power in law-making (nn.32–33, OP), while multilevel inter-institutional relations increased their bargaining and political features (Baldini and Baldi, Reference Baldini and Baldi2014; Bolgherini et al., Reference Bolgherini, Di Giulio and Lippi2018b).

Discussion

The sets of evidence Before/After-2012 (Tables 1 and 2) displayed according to the analytical dimension (legal, organizational, functional, and political) and crossed with the LAI scopes (self-rule and shared-rule) are now discussed together. Tables 3 and 4 provide synthetic overviews of all evidence of straight- and oblique-change, and account for their incidence (per dimension and scope) by employing some simple descriptive indicators.

Table 3. Assessment of the impact of straight- (SPs) and oblique-change provisions (OPs) on the overall LG institutional change in terms of frequency and magnitude/intensity, per dimension and scope

Source: Authors' compilation.

Note: Magnitude values have been assigned according to the percentage of OPs out of the total provisions: 1 when the percentage corresponds to below 33% of the total; 2 if between 33 and 49%; 3 if between 50 and 74%; 4 if between 75 and 89%; 5 if between 90 and 100%. Intensity labels are assigned accordingly: low if 1; medium if 2; high if 3; very-high if 4; extreme if 5.

Table 4. Assessment of the impact of oblique-change and provisions (OPs) on the overall LG institutional change in terms of direction and prevailing trend of change, per dimension and period

Source: Authors' compilation.

The first indicator (Table 3) is the frequency, that is the total number of SP and OP occurred in a dimension of local government in both first (before-2012) and second (after-2012) period, and on both self-rule (SeR) and shared-rule (ShR). To assess the impact of oblique-change, figures on the total OPs out of the overall provisions per period and dimensions are displayed.

The Magnitude refers to the degree of OP-driven change according to an ordinal scale ranging from 1 to 5, while Intensity points accordingly, meaning to what extent (low to extreme) OPs impacted Italian LG's change.

Table 3 displays the evidence that OPs do account for largely more than half of the total change in LG in both periods. Before-2012, more than three-quarters of the enacted measures (33 out of 43, namely over 76%) were OPs; after-2012, this figure remained over 65% (21 provisions out of 32). In both cases, along with the political dimension – where an oblique more than a direct impact is to be expected in a form of a spillover – the organizational and the functional dimensions are the most numerically affected by this type of institutional change.

More analytically, on the legal dimension, we can observe how oblique changes had a medium (before-2012) and low (after-2012) impact on the overall institutional change. In contrast, on the other three dimensions, it ranged from high (on the functional dimension in the after-period) to extreme (on the same dimension before-2012, on the organizational one after-2012, and on the political dimension in both periods). Finally, on the political dimension, a change is to be detected on the self-rule since the role of political parties at the local level did remain unaltered and quite independent from the decreasing grasp of the central party apparatus on its territorial articulation.

Table 4 displays the fourth descriptive indicator, that is, the Direction, which indicates, for each of the two periods, if the institutional change points globally toward an extension (E) or a retrenchment (R) of the Italian LG autonomy. The total number of retrenchments in the first period is 20 against the 23 provisions implying an extension, while after-2012, the retrenchments neatly overcome the extensive provisions (23 against nine, respectively).

The overall picture is thus one of a moderate extension of LG autonomy before the global crisis and one of a more definite retrenchment in the post-2012 period. However, no clear trend toward a specific direction can be easily or assertively detected: both extensions and retrenchments co-exist and overlap, both within the single dimensions and within groups of provisions dealing with the same topic.

Getting a glance at the single dimensions, we observe that, passing from the first to the second period, an overall retrenchment overcomes extension on two dimensions (organizational and functional). In the latter, from a slight extension, the trend changes to a remarkable retrenchment, while on the organizational dimension, the already present retrenching trend does even increase. The opposite occurs on the political dimension where the extension prevails – and even increases in the number of provisions – in both periods, while on the legal dimension, the extensive moderate trend in the before-2012 years swings to a somewhat stronger retrenchment in the second period.

On the legal dimension, the final retrenchment is mainly due to the return to an indirect election for the second-tier authorities (provinces) and to the implications of the 2014 Delrio law, which was the reform that mostly impacted Italian LG after those of the early 90s. On the organizational dimension, the even increasing retrenchment from the first to the second period is attributable to all those provisions questioning or shrinking the local authorities' autonomy, that is, all the constraining rules for hiring, for accounting, for reporting, for keeping local authorities updated, etc., enacted after the global crisis, that exacerbated the pressure on the already tightening organizational margins for LG.

On the functional dimension, the post-2012 retrenchment in favor of the central State emerges, particularly as far as the fiscality variables are concerned. The austerity measures introduced with the global crisis entailed decreasing options for self-taxation, increasing fiscal constraints, and tighter administrative supervision on expenditure: no surprise that this fiscal curbing strongly marked LG autonomy.

Finally, on the political dimension, even more substantial influence of local politicians at the central level is to be detected, or, as Page and Goldsmith (Reference Page and Goldsmith1987) Goldsmith and Page (Reference Goldsmith and Page2010) put it, the access of local politics to the national level has increased. The prominent role of local politicians (primarily mayors) in the even more politicized intergovernmental arena of the after-2012 period, as well as the enhanced lobbying activity from the part of the territorial associations (in particular that of the municipalities – ANCI) has in fact sensibly grown in the after-2012 phase, here even amplified by the overall fragility of the national party system.

To sum up, institutional change in Italy in both phases (Before- and After-2012) was mainly steered by OPs, both in terms of frequency and in terms of magnitude and direction of change. Change happened along all four dimensions and variables of the two self- and shared-rule scope of local autonomy, with provisions ranging from austerity measures (expenditure caps, hiring freezing, etc.), to small organizational and functional norms (rules for personnel, public–private relations, etc.), to different power allocations. Our evidence thus shows that oblique-change neatly dominates on straight-change when assessing the overall institutional change over the two periods.

Conclusion

This article shed light on oblique-change as a heuristic category to understand institutional change in local government. The underlying assumption derived by several strands of literature is that along with direct and explicit reforms, LG is regularly and commonly affected also by indirect re-adjustments that incrementally contribute to its evolution. Following this heuristic aim, we singled out two types of provisions – OPs and SPs – leading to two types of institutional change: oblique-change and straight-change, respectively. While straight-change is visible and deliberated, and officially explicit – pursued, for example, through Constitutional change and major LG-reforms – oblique-change is induced by indirect provisions, often stemming from other policy fields, for example, by cross-sectoral legislation, organizational or budgetary regulations.

Our Before/After-2012 analysis and our assessment of the impact of oblique-change on the overall institutional change and LG autonomy let some main findings emerge.

The first is that the pre-eminence of oblique-change is time-invariant. In terms of numerosity and frequency, our evidence shows that since the 1990s, oblique-change has neatly prevailed on straight-change, and that in both periods it accounted for well over a half of the collected provisions. OPs concerned both the self- and the shared-rule of local autonomy, and highly impacted the legal, the functional, and the organizational dimensions, while less the political one. This evidence is not at all surprising: LG is intrinsically subordinate to decisions imposed by the State, be it the central government, the Constitutional Court, or other central authorities, agencies, and bureaucracy. As a consequence, LG is invested in its everyday life by a plethora of many different provisions of various nature that – when not directly addressing legal features – usually impact first functional and organizational aspects, and only later, they may rebound on political aspects. This has been particularly evident during the austerity years, when LG was affected by different types of OPs that put it under unprecedented pressure. Nevertheless, the evidence in the first period does support the same picture. Moreover, the magnitude and the intensity of oblique-change out of the total change oscillated in the two periods between high to very high, thus confirming the notable impact of this type of change on the overall trend.

The second finding is that LG's autonomy in Italy has not faced a radical transformation in the years of the global crisis. On the contrary, local autonomy experienced a significant re-arrangement caused by many SPs and many more OPs that affected it, sometimes in terms of an extension, sometimes of a retrenchment. Indeed the direction (extension and retrenchment) of change turned out to be highly variable. The collected evidence showed that extension and retrenchment are co-existing and overlapping both before- and after-2012, all along self- and shared-rule and all four dimensions. True, there are pre-eminent temporary trends (such as toward retrenchment during the austerity wave), but they usually proved to be neither definitive nor static. This holds true both as a general trend, and as evidence in the single policy areas: the continuous swinging between extension and retrenchment of local autonomy in the LPSs domain, or in the personnel management, are emblematic examples in this respect.

Third, this article showed to what remarkable extent oblique-change matters, and how it is much more frequent and highly impacting than expected. Our evidence indicated that institutional change affects all four dimensions (legal, organizational, functional, political) and both self- and shared-rule of local autonomy, and that its final output is determined by both straight- and oblique-change. It also revealed that the latter indeed proves to matter to an unexpected significant extent: oblique-change induces as permanent and profound institutional change as the one produced by LG-focused reforms (straight-change) and equally alters the overall local autonomy. However – and this is the most noteworthy point – this change could pass undetected if analyzing SPs only. Oblique-change works in fact in a way that is more similar to a ‘bradyseism’ than to an ‘earthquake’, which is instead what a straight-change may provoke. Like in geology, bradyseismic adjustments are indirect, slower, and more localized than violent earthquakes, although not at all irrelevant. Just the opposite: while at first glance they seem to have changed nothing, a more in-depth analysis, or the passing of time, show how deeply and permanently the bradyseismic adjustments have affected the previous situation. Trailing this metaphor, our analysis demonstrated that Italian LG precisely experienced, since the 90s and throughout the global crisis, a bradyseismic institutional change.

Funding

The research received no grants from public, commercial or non-profit funding agency.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Maria Chiara Cattaneo for her help in the systematic gathering of the legal sources. We also want to thank the anonymous reviewers and the Editors for their valuable suggestions for improving the previous version of this paper.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2020.29.