In its attempt at reviving relations with sub-Saharan Africa, Italy adopted a number of initiatives and tools similar to those introduced by several other countries that recently stepped up their engagement with the region, except that all was done with a time delay of a few years. Italy's remarkable, sudden and unforeseen transformation of its policy towards a previously neglected area (Africa), as well as the comparatively late timing of the policy shift (2013–2020), raises key questions as to the rationale, autonomy and interests behind the country's foreign policy-making. As a relative latecomer, was Rome stimulated by the will to learn from and emulate other European countries, to catch up and compete with them? Were Italy's choices, in other words, the result of policy diffusion? Examining whether, how and to what extent the country ‘drew lessons’ from outside is both a test of diffusion theory in foreign policy-making and a step to fully understand the rationale and design of Italy's Africa policy and explain its outcomes.

This paper traces the process of policy-making by building on multiple sources of evidence, including semi-structured interviews with policy-makers, content and discourse analysis, web analytics, public opinion surveys, statistical data series and primary documentation such as parliamentary records, party manifestoes and official ministerial or government texts. It investigates the timing, actors, strategy, tools and motivations behind Italy's Africa policy and relates it to equivalent policies that have been introduced elsewhere. It ultimately shows how Italy's new course was only partially influenced from the outside – implying that the diffusion hypothesis is only marginally helpful – since it primarily emerged as a self-driven reaction to motives that were largely unique to the country. The paper thus sheds light on how the marked resemblance of policies almost contemporaneously adopted by distinct EU member states (EUMS) can hide motives and processes that are highly specific to an individual country.

Policy diffusion and the proliferation of African strategies in Europe

Europe's historical and geographical connections with Africa run deep. That a steadily growing number of EUMS introduced new Africa policies in recent years is rather surprising, however, particularly when compared to a preceding period during which the region had been essentially deserted by the West. When, between 2020 and 2021, little Malta and Estonia introduced their own Africa plans, they were only the latest in a string of European states that adopted analogous schemes, including Spain (in 2006, 2009 and 2019), Germany (2011, 2014 and 2019), Denmark (2013), Poland (2013), Slovenia (2017), Hungary (2019), Ireland (2019), Malta (2020), Italy (2020), Finland (2021) and, as mentioned, Estonia (2021) (Carbone, Reference Carbone2020; cf. Faleg and Palleschi, Reference Faleg and Palleschi2020). France and Portugal had never relinquished their privileged connections with former colonies – so deep-rooted and intense, particularly for Paris – albeit without single policy documents spelling out the latter's underpinnings. On the face of it, the staggering proliferation of Africa plans in such a tight succession and in a highly interconnected environment suggests that they might have been somehow linked to each other.

The notion that policies ‘diffuse’ is commonly used to investigate how the policies of a given country (or a political unit of a different type, such as an autonomous region or city) are influenced by those of other countries or units. Policy diffusion thus refers to ‘a process of interdependent policy making’ that analysts of public policies, comparative politics and international political economy examine with a primary focus on the role of external determinants (Gilardi and Wasserfallen, Reference Gilardi and Wasserfallen2019: 1246). It has a significant overlap with the concepts of ‘lesson drawing’ (Rose, Reference Rose1991) and ‘policy transfer’, in which ‘knowledge about policies, administrative arrangements, institutions and ideas in one political system … is used in the development of policies, administrative arrangements, institutions and ideas in another political system’ (Dolowitz and Marsh, Reference Dolowitz and Marsh2000: 5). The notion of policy diffusion typically emphasizes structural factors and non-intentional processes, and is more frequently used in quantitative research, whereas the idea of policy transfer is more commonly employed for case studies and often privileges a focus on the role of knowledge and intentional processes (Obinger et al., Reference Obinger, Schmitt and Starke2013: 113; cf. Wasserfallen, Reference Wasserfallen, Ongaro and van Thiel2018: 624).

The underlying elements of policy diffusion are temporal waves, spatial concentration and policy commonalities in diverse national settings (Weyland, Reference Weyland2005: 265). While interdependencies in policy-making had already long been noted – with regard, for example, to post-World War II welfare states building – since the 1980s the spread of globalization and the process of European integration gave additional impetus to the role of external influences in domestic policy-making (Obinger et al., Reference Obinger, Schmitt and Starke2013: 112–113). The latter also led to the expansion of studies of Europeanization and EU conditionality, which are close to, if distinct from, analyses of policy diffusion: while similarly aimed at shedding light on interdependencies in policy-making, they retain a primary focus on vertical linkages with Brussels (e.g. Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier, Reference Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier2004; Börzel, Reference Börzel, Bulmer and Lequesne2005), rather than on influences between EUMS (Wasserfallen, Reference Wasserfallen, Ongaro and van Thiel2018: 623).

The presence of ‘highly clustered policy making’ thus does not necessarily amount to a diffusion process (Simmons and Elkins, Reference Simmons and Elkins2004: 172). Other, alternative, non-diffusion explanations – including ‘policy convergence’ – are also arguably more appropriate in framing situations where governments respond similarly, but independently, when facing the same kind of shocks or macro-conditions, such as a pandemic, an economic crisis or climate change. Policy independence is therefore the opposite of the interdependency that, by definition, underlies policy diffusion.

The policy diffusion literature identifies four core mechanisms through which the process may take place (cf. Simmons et al., Reference Simmons, Dobbin and Garrett2006; Obinger et al., Reference Obinger, Schmitt and Starke2013; Gilardi and Wasserfallen, Reference Gilardi and Wasserfallen2019: 1247ff.). The first is learning, whereby decision-makers choose on the basis of a rational (or quasi-rational) appraisal of what particular policies have actually produced elsewhere, and are primarily influenced by policy success stories in addressing the same kind of problems they face. What are perceived as ‘best practices’ based on the experience of other countries guide policy-makers in shaping their own interventions, that is, in adopting or adapting specific sets of measures. Learning can be both positive (when success makes policies attractive) as well as negative (when policy failures abroad invite to avoid certain strategies or instruments). In practice, though, information shortcuts – such as assessments based on outcomes only, or reliance on existing knowledge and networks – are often employed to avoid incurring the full costs of more complete and detailed analyses.

A second mechanism is competition, which is based on a strategic dimension of the interactions among different countries. Here, the policies decision-makers adopt are typically meant to entice investments and resources – for instance, via business or trade regulations and taxation – and they are thus influenced by the policies of countries with which they compete for these same material rewards. While not widely covered in the literature, diffusion in the foreign policy sphere may just as well be a response to international geopolitics and rivalries, where returns are not necessarily material but may have to do with power, political influence, status or symbolic goals. When economic or political competition drives the diffusion or transfer of a given policy, what matters is the comparative advantage a country aims at, or the disadvantage it wants to avoid. The underlying assumption is that the relations that count are horizontal, as it is the ‘policies of one's economic [or political] equals’ that matter the most – those of the main trade competitors or same-level powers, for example – leading, in principle, to policy clustering ‘among countries located within the same competitive networks’ (Simmons et al., Reference Simmons, Dobbin and Garrett2006: 793).

Thirdly, the perception that a given policy is appropriate may lead a country to emulate other states for reasons that have little to do with the actual outcomes such policy is expected to produce. In this case, there is no specific ‘problem’ to solve. Thus, rather than a rational assessment of which means and actions will best enable the achievement of a certain set of goals, it is the normative meaning of a policy – for example, education for all, gender equality, green transition or the abolition of capital punishment – that is prioritized so to have the country conform to the legitimizing values and symbolic standards that predominate in the external environment.

Finally, a fourth way the same or similar policies may spread among different countries is via coercion, that is, when policy changes are imposed by the pressure that powerful countries or international organizations bring to bear on policy-makers. Most notoriously, economic and political conditionalities have been a commonly used tool to have developing countries accept policies promoted by the World Bank, the IMF or other external actors. Embargoes, economic sanctions or trade practices are another way pressures can be exerted from the outside for policy makers to adjust their course of action.

None of the above processes evidently occurs in a vacuum, or a ‘neutral’ setting, but rather takes place in the highly specific context of the recipient country. Crucially, the nature of the latter's existing external relationships – most notably in terms of scope, strength, depth, distance, dependence, and of political, economic and cultural similarities – is bound to affect the likeliness and nature of any process of policy diffusion, including the extent of adoption and adaptation. Europe – and the EU in particular – represents a tightly connected external environment in that ‘decision-makers on the local, national and supranational level cooperate, exchange information, learn from the successes (and failures) of others, compete for power, and scapegoat one another’ (Wasserfallen, Reference Wasserfallen, Ongaro and van Thiel2018: 621). Policy diffusion has been documented to have occurred in different policy sectors.

Africa policies or strategies are hereafter used to refer to plans adopted by non-African governments that include the identification of a country's own goals in its relations with the continent (or with the sub-Saharan region) alongside the guidelines and tools that are meant to be employed in order to achieve them. European states have not been the only ones turning to Africa over the past 20 years. Several other foreign players invested political and economic capital in the area, reversing the widespread neglect that had prevailed during the latter decade of the past century.

While the temporal clustering indicates that many such countries were also likely subject to some kind of external influence on policy-making, the striking proliferation of Africa strategies across the closely interrelated spatial and political environment European states belong to makes the possibility that choices in one country were affected by those of others all the more plausible. As a matter of fact, one would be hard pressed to find alternative explanations for states such as Slovenia, Estonia or Malta, which were arguably ‘least likely cases’ in the adoption of relatively far-reaching and demanding foreign policies.

Research design, methods, sources

While the propagation of Africa strategies among European states strongly suggests a policy diffusion process, a closer empirical investigation is ultimately required to disclose and prove whether this is actually what happened. This paper focuses on the Italian case. Examining whether, how and to what extent Italy learned, emulated or competed when assembling its Africa policy serves both as a test of the diffusion hypothesis and as a way to examine what Rome wanted to achieve and how it set out to attain it, with a view to explaining the policy's actual outcomes and prospects.

The paper thus offers a study of the making of a policy – specifically, a policy for Africa – as a process delimited both in space (Italy) and time (2013–2020). Policy diffusion theory, as pointed out, is employed as the starting theoretical framework, a possible explanation rendered most plausible by the previous or almost simultaneous adoption of similar policies across the EU. The analysis would contribute to better understanding how and to what extent the foreign policies of EUMS are shaped by cross-border influences horizontally (i.e. through the initiatives of other member states, a form of ‘Europeanization’ of policies in a broad sense) as well as vertically (i.e. through EU initiatives, the so-called ‘Europeanization’ of policies strictly speaking). Moreover, the diffusion account would be particularly relevant and revealing for grasping the role of external influences on the making of Italy's foreign policy per se.

The paper argues, however, that diffusion was not central to Italy's policy-making: empirical evidence in support of the starting hypothesis is quite limited and far from compelling. The case study shows that the striking simultaneity of EUMS's Africa policies cannot be accounted for through the intuitive idea that diffusion somehow took place. This result is itself a relevant contribution, against the practice of not reporting negative or inconclusive results, which generate a loss of information and thus biased knowledge (cf. Scargle, Reference Scargle2000; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Green and Nickerson2001; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Malhotra, Dowling and Doherty2010).

The paper, however, does not leave the question of explaining the making of Italy's Africa policy unanswered. On the contrary, out of the research conducted to test the diffusion hypothesis, a rival and stronger explanation is elaborated that identifies and builds on two country-specific domestic drivers of the policy-making process. Thus, the second part of the paper develops as an ‘a-theoretical’ (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1971) or ‘configurative-ideographic’ (Eckstein, Reference Eckstein, Greenstein and Polsby1975) case study, a strategy recently described by Bennett (Reference Bennett2015: 209) as taking ‘the form of a detailed narrative or ‘story’ presented in the form of a chronicle that purports to illuminate how an event came about. Such a narrative is highly specific and makes no explicit use of theory or theory-related variables’. The aim is to complete the analysis the paper set out to do by tracing comprehensively the policy-making process and providing an evidence-based explanation for it.

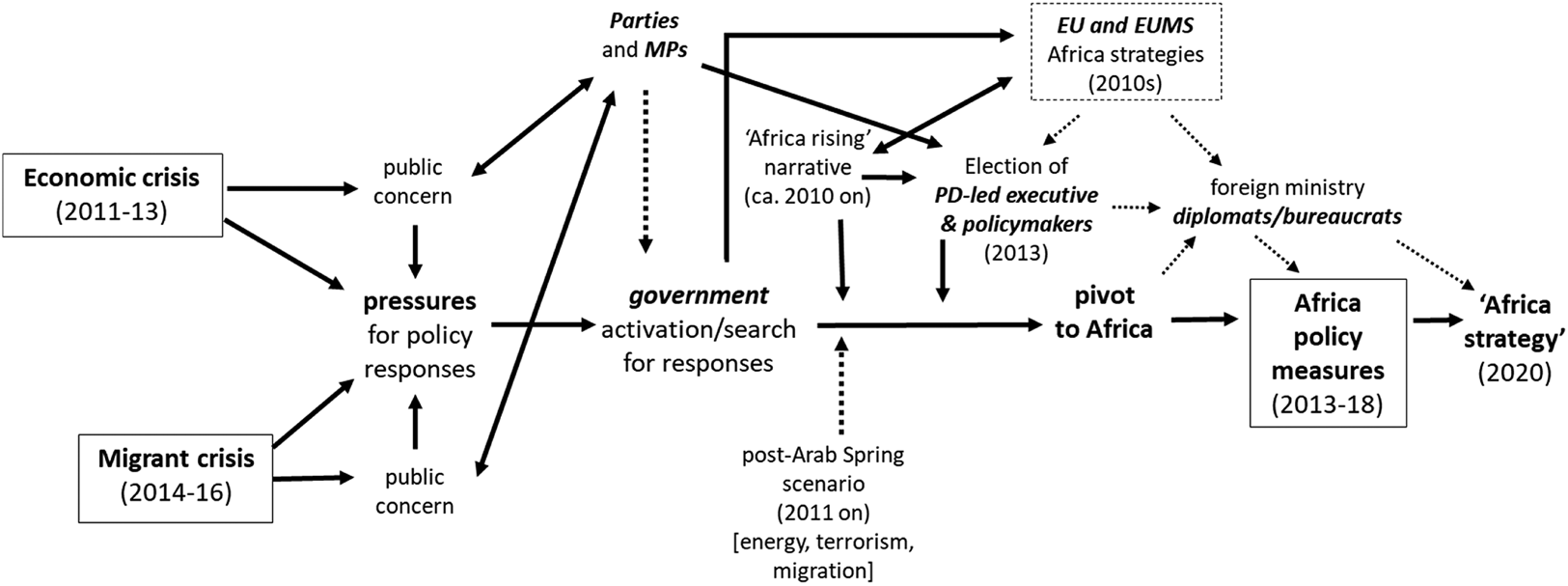

The main roots of the process are found in two sources of pressures the country had to face, in tight sequence, which were primarily domestic, if not lacking an external origin: the economic crisis of 2011–13 and the migrant crisis of 2014–16. Following Gerring's (Reference Gerring2007: 181–182) methodological guidelines for process tracing, in Figure 1 a graphic representation structures and anticipates the steps in the causal chain leading from these primary drivers to the policy outcome – a process whose components are traced and unpacked in the next sections – while also accounting for how specific variables, dynamics and players interacted (cf. Vennesson, Reference Vennesson, Donatella and Michael2008: 236). The starting point is that, in a quick succession, the two crises produced significant if distinct pressures for the government to respond, including indirectly by generating widespread public concern and by raising increased attention among political parties and MPs. As part of the responses to such pressures, from 2013 a newly elected government led by the centre-left Partito Democratico (PD) built on the spread of an international narrative about the growing relevance and potential of African countries, and on the rapid unfolding of a post-Arab Spring scenario that invited Italy to look beyond north Africa, to initiate the country's pivot to Africa. In the space of a few years several decisive measures were undertaken, mostly articulated via the foreign ministry, which fundamentally re-shaped Italy's engagement with the sub-Saharan region. The 2020 Africa strategy was essentially an ex post effort to outline what by then had already been done or at least started. Over the entire process, the EU and its member states (EUMS) – that is, the potential key sources of policy diffusion for Italy – were not entirely out of the picture, but their roles and their external influence on policy-making were largely secondary.

Figure 1. Tracing policy-making in Italy's shifting approach to Africa.

Note: Key actors in italics.

Strictly speaking, from a methodological point of view this study goes beyond the focus on a single ‘case study’. The analysis builds on an implicit within-case diachronic, or longitudinal, comparison to the extent that it is based on observing changes (or lack thereof) both in policy-making and in its explanatory factors during the 2013–20 period as opposed to the pre-2013 period. The latter thus somehow acts as a control, implying a logic of the research design that is similar to a quasi-experiment: examining policies at different points in time in the same country – with the latter's structural characteristics essentially remaining the same – helps meet the ceteris paribus condition required by any meaningful comparison (Eckstein, Reference Eckstein, Greenstein and Polsby1975: 85; Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1975: 160; cf. Gerring, Reference Gerring2007: 21, 30–31). The counterfactual hypothesis is thus continuity, that is, the possibility of ‘no change’ in policy over time: Italy had long disregarded sub-Saharan Africa and, in the absence of two new drivers (i.e. the economic crisis and the migration crisis) and of favourable contextual conditions (most notably, the post-Arab spring scenario, the international ‘Africa rising’ narrative and a pivotal centre-left political force), there would have been no strong reason nor push for reshaping Italy's course of action south of the Sahara, particularly so since the region was previously not only overlooked, but somewhat avoided as a perceived ‘high risks/low benefits’ area. Yet, rather than policy continuity, we observe substantial change in the direction and scale of Italy's Africa policy from 2013 on, first at the level of the political discourse and then in terms of the practical foreign policy actions that were commenced. To fully appreciate the recent changes in Rome's approach to Africa, the next section starts by contextualizing it within the long-term evolution of Italy–Africa relations.

Evidence for the argument developed in the paper was gathered through a variety of techniques and sources. Besides an analysis of numerous key government policy documents, the author conducted a number of semi-structured interviews with policy-makers, including interviews with a former Minister for Foreign Affairs, a former Minister for Defense, a former Vice-Minister for Foreign Affairs, a former Vice-Minister and Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, the Central Director and Deputy Central Director for sub-Saharan Africa at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and key MPs/former MPs. Data from Factiva and Nexis Uni news databases were used to trace news coverage of Africa on Italy's six main national newspapers, selected with an effort to balance different positions (Corriere della Sera, La Repubblica, La Stampa, Il Sole 24 Ore, Il Giornale, Libero). Data from different public opinion surveys were used to trace relevant trends in Italian public opinion on migration and on the economy. A content analysis of parliamentary speeches (2000–2020) in the Italian parliament was conducted to again search for trends in the use of key terms related to the topics of the paper (the database I used is not yet publicly availableFootnote 1). A similar content analysis was performed for seven Prime Ministers' investiture vote speeches in 2011–2021 and for the manifestos of the main political parties in Italian elections during the 2010s. Finally, a more informal source of information was direct participant observation through my consultancy work for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, activities that implied repeated exchanges, discussions and involvement in some policy projects.

Italy and post-independence Africa

After losing its Libyan and Horn of Africa colonies during World War II – and following the 1960 end of the trusteeship on Italian Somaliland granted by the United Nations – Italy had gradually reduced its attention towards the sub-Saharan region, particularly after the 1980s. The country tended to look north, towards Europe, rather than south. And when it did look south, its attention mostly stopped at the opposite shore of the Mediterranean or else was directed towards the Middle East. In the Horn itself, post-colonial relations with Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia were only fostered to a limited degree. While Rome did consider the area as something akin to France's pré carré in West Africa, a relatively superficial colonial occupation had not left any enduring neo-colonial networks (Calchi Novati, Reference Calchi Novati2008: 54). Nor did Italy host substantial diasporas from these countries that would nurture a continued relationship.

Development aid to sub-Saharan Africa had increased substantially during the 1980s – with Italian Official Development Assistance (ODA) second only to France's in the latter half of the decade – but it then collapsed and stabilized at comparatively very low levels. Hardly ever the subject of public debate and awareness, development policy lingered at the margins, poorly understood, unclearly framed and dealt with as a residual policy (Carbone and Quartapelle, Reference Carbone and Quartapelle2016: 45). The major political parties themselves had only scantily linked with the likes of Somalia, Ethiopia and Mozambique. With the exception of ENI's activism in Africa's oil and gas sector, commerce and investments also remained fairly limited, with the country running a historical trade deficit largely due to energy imports.

A perception of Africa as a source of multifaceted and essentially intractable problems, with barely any opportunities, overshadowed most other concerns and led to contain any engagement. Responsibilities, if any, were left to the goodwill and activities of Italy's numerous NGOs and Catholic missions – from Jesuits in Chad and Salesians in Angola to Combonians in Uganda or Kenya – which, in many places, still maintain a deeply rooted presence today. What is at times referred to a traditional focus on ‘people-to-people’ relations (Mistretta, Reference Mistretta2021: 109). It was not by chance that Italy's only ‘official’ success over the entire period resulted from a peace deal mediated by the Sant'Egidio Community and signed by Mozambique's two warring sides in Rome, in 1992. The other way the country remained somewhat active in the region was by adhering to multilateral initiatives, including peacekeeping operations. Direct participation in some 30 international missions Italy contributed to, however, was typically quite limited. A key exception was the large number of troops committed to the UN mission to Somalia, also in the early 1990s. But the failed operation seemed to further prove the wisdom of staying away from the region.

Italy's overall neglect of Africa for the better part of three decades was best illustrated by the lack of a single prime ministerial bilateral visit south of the Sahara between 1985 and 2014. Well into the new millennium, the extent of the country's diplomatic and cultural network compared poorly with the likes of Germany, the UK or France, with only 19 embassies and three cultural centres across sub-Saharan Africa's 49 states. West Africa alone counted a mere four embassies (in Senegal, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana and Nigeria), and the whole of the Sahel just one (in Sudan). Africa struggled to gain more room in Italy's diplomacy, development cooperation and economic relations.

Rome's turn to Africa

Italy was a latecomer in turning to Africa. Some early if rather isolated initiatives had been devised between 2007 and 2009. Most notably, an Italian Africa Peace Facility was created with the aim of supporting African Union's actions related to peace and security. None of the early attempts at introducing change, however, was part of a broader strategy, nor did they have any lasting impact.

It was in the early 2010s that the domestic and international scenarios simultaneously evolved in ways that favoured a much more substantial transformation in Italy's course of action. On the external front, the Arab Spring implied Rome no longer had privileged links to Libya, leading to look beyond the Mediterranean shores in order to safeguard energy security, manage migration and find new markets. On the domestic side, a new legislature emerged with a centre-left coalition as its main force, if lacking majority control, which allowed the formation of governments that were arguably more sensitive to African issues. This opened a significant window of opportunity. Ultimately, the governments that were in office during 2013–2018 would embark in a period of considerable, sustained and strategic attention towards Africa – and away from areas such as Iraq and Afghanistan.

The starting point was the Italy–Africa Initiative launched by the foreign ministry in late 2013. The aim was to stimulate public awareness of the continent by emphasising the ‘virtuous dynamics’ taking place on the continent and the opportunities that ‘positive economic prospects’ offered for Italy and its small and medium enterprises (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2013). Opening new markets to Italian businesses, many of which had for years faced persistently weak domestic demand, was deemed strategically crucial for the country's economic recovery (a point that is examined below).

A substantial diplomatic drive quickly gained traction. The shift was unmistakable in the impressive string of seven bilateral state visits to a total of 12 sub-Saharan countries, during 2014–2019, by three successive Prime Ministers. The President of the Republic added another two nations by twice travelling to the area too. Diplomatic initiatives also took a more stable form with the inauguration of five new embassies between 2014 and 2020, bringing the total in the region to 24, up from 19, or a hefty +26% increase. A permanent representative to the African Union was also appointed in 2018.

At home, on the other hand, Rome organized and hosted two Italy–Africa ministerial Conferences, in 2016 and 2018, to encourage closer ties with African countries and the AU. This was, once again, entirely new. In his concluding remarks for the first conference, Prime Minister Matteo Renzi stressed an economic rationale as the first reason for Italy and Europe to look south and open to Africa, setting this motive explicitly apart from migration. The latter only came second in the agendaFootnote 2. All the same, it was on this occasion that the Italian proposal for an EU Migration Compact was unveiled. Priorities were in fact shifting, something we will come back to.

Italy's new impetus towards Africa also helped force through the overhaul of development assistance that actors from the third sector had long asked forFootnote 3. A 2014 reform led to the creation of an autonomous Italian Agency for Development Cooperation (AICS), aligning Rome with prevailing practices across Europe. The ministry itself was symbolically renamed Ministry for Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation (MAECI). This was accompanied, between 2012 and 2017, by an overdue upward trend in the country's limited ODA, with Rome climbing from 10th (2015) to 6th (2017) position among international donors in terms of absolute volumes. Reflecting foreign policy purposes, however, the AICS's priorities would place centre stage not just agriculture and food security, but migration too. A new Fund for Africa set up in 2017 further revealed the intermixing of development and security goals, again essentially meaning migration.

Geographically, the focus of Rome's concerns gradually turned to the Sahel, whose ‘extreme importance’ to Italy (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2020a, 2020b: 23) – a true and key novelty when compared to the country's traditional areas of interest – came from it being perceived as a ‘southern border of Europe’. While France's engagement in the Sahel was primarily sparked as a response to the jihadist threat and a defence of its sphere of influence, however, Italy's concern with security in the area was dominated by the control of migration routes. Building on the recently increased bilateral diplomatic presence, with new embassies in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso and a fourth one in Chad unofficially announced, as well as on the launch of a military training mission in Niamey (see below), the government committed to multilateral cooperation too, participating in a number of EU, UN and, from 2020, even French-led operations in the area.

Besides the pursuit of national interests, involvement in the Sahel offered an opportunity to raise Italy's profile and assertiveness within the EU and its Africa policy. By 2021, the appointment of a former vice-minister of foreign affairs, Emanuela Del Re, as EU Special Representative for the Sahel, proved an external recognition of Italy's growing role in the area.

The second privileged geographical area was the Horn of Africa and Red Sea (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2020b: 46), a quadrant that, based on a recently emerged international notion, expands eastward beyond Africa's shores. Here, it was Italy's historically rooted relations with the Horn that called for a substantial role, with security and stability issues topping Rome's agenda. Besides taking part to EU missions for state-reconstruction in Somalia and anti-piracy operations, an armed presence in the Horn was established with an Italian military base in Djibouti, in 2013, and agreements for training security forces were signed with both Somalia and Djibouti.

Italy's southbound shift towards a much-increased engagement with sub-Saharan Africa culminated in a comprehensive strategic document – the first ever devoted to the region – issued in December 2020. With the aim of promoting both the country's national interests and a balanced growth in the region, a partnership with Africa was meant to guide action in the medium-to-long term via ‘an all-out engagement that is continuous, not sporadic, and above all committed’ (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2020b: 54). The true nature of the ‘new’ plan, however, was ultimately that of an ex post policy. That is, an effort to bring together what Rome had being doing over the previous years in its relations with the continent, and to foster attention towards the latter so to retain a degree of continuity following the policy innovations of 2013–18. What had been started already, the underlying message was, should not be dissipatedFootnote 4.

Diffusion mechanisms at work?

Italy's own take on Africa was revived building on the backdrop of the ‘emerging Africa’ narrative that had gained worldwide currency since around 2000 and led many countries to launch new initiatives targeting the continentFootnote 5. Coverage of Africa's economic performances on Italy's six main national newspapers began rising gradually since around 2005–2006, having started from a level close to total neglect, until it reached its highest peak in 2011 – when coverage was 20-to-40 times stronger than it had been in 2000 – and remained sustained until the pandemic struckFootnote 6. The new storyline first made a minor appearance in official documents around 2009, went on to become the rhetorical argument behind the Italy–Africa Initiative of 2013, and was then more systematically embraced by the coalition government that held office during the subsequent three years. By now, it was squarely aimed at promoting the image of ‘a future in which Africa is not considered … the biggest threat, but it is objectively the greatest opportunity for Europe’Footnote 7. Party manifestos were also making room for Africa, if with some delay. While none of the 2013 electoral programmes of the three main political coalitions or forces (i.e. centre-right, centre-left, Five Star Movement) mentioned the continent, five years later the latter had made it in two out of three. All this represented a crucial adjustment in the terms of the debate, and was instrumental to adopting a new approach. It turned out a main lynchpin linking the beliefs and behaviour of key policymakers.

Drawing from international ideas thus allowed Rome to frame Africa under a new light, conveying an image of the continent that was both more appealing and more in line with global trends. Rome's swift shift therefore included an element of inspiration and learning from the outside. Back in 2013, for example, an explicit awareness of foreign examples had encouraged the idea of holding biennial Italy–Africa conferences along the lines of those organized by the likes of China, France, Japan, Brazil and TurkeyFootnote 8. The Partenariato itself would eventually acknowledge external influences when stating that, ‘similarly to what has been done by other EU partners (France, UK and Germany), it is … necessary to develop a comprehensive action’ (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2020b). The path followed by major European economies supported the notion of opening to Africa.

A conscious effort was made, however, to differentiate Italy from its competitors by adding two distinct twists to the emerging international storyline on Africa. First, Rome routinely tried to portray its actions as being ‘disinterested’, ‘respectful’ and ‘value-oriented’Footnote 9. Historically, it was claimed, Italy's relations with the region had been benevolent as much as beneficial; ethical and devoid of any hidden geopolitical agendas (Lobasso, Reference Lobasso2021: 2; Mistretta, Reference Mistretta2021: 106). While the likes of the French, the Americans, the Russians or the Chinese often stirred suspicion and resentment, Italians were supposedly ‘trusted’ and ‘welcome’ by Africans across the continent, a direct implication of the self-portrayed image of italiani brava gente (Italians are good people).

Secondly, Rome repeatedly bet on the ‘Made in Italy’ brand, that is, on the idea that, in sectors from agribusiness to design, from renewables and industrial machinery to big infrastructures, the country can supposedly showcase and rely on its renowned quality and world-famous ‘excellence’. Moreover, the very structure of the Italian economy, whose backbone primarily consists of a vast number of small and medium enterprises, as opposed to large firms or conglomerates, was claimed to best fit Africa's needs to move its mainly informal economic activities towards small formal businessesFootnote 10.

With Africa increasingly a place crowded with foreign players, international economic and political competition also advised that Italy scrutinize their moves. Following into the steps of others would help catch up before it proved too late. Italy's aspirations in Africa were made all the more legitimate by the very fact that, as a diplomat put it, ‘our competitors make no mystery … that they have their own national strategies and agendas’ (Mistretta, Reference Mistretta2021: 111). A logical consequence was the adoption of comparable actions, such as the expansion of embassies or Prime Ministerial visits, the Africa conferences or military deployments.

The effort to gain a foothold in the Sahel, a zone of long established French influence, was a prominent example of how the country's more open pursuit of national interests intertwined with diplomatic competition. Developments in post-2011 Libya – where the US was reluctant to take the lead, tensions with France were growing and Rome was experiencing an evident decline of influenceFootnote 11 – convinced Italy of the need to enter the Sahel, traditionally part of a French sphere of influence, in a more autonomous way. Niger thus emerged as a key ‘arena of strategic positioning’ as, following the opening of an embassy and the channelling of substantial amounts of aid, a bilateral defence agreement and the deployment of Italian troops were deemed ‘not only a tool to control migratory flows but also to gain a military footprint in the Sahel’ (Tiekstra and Schmauder, Reference Tiekstra and Schmauder2018; cf. Strazzari and Grandi, Reference Strazzari and Grandi2019: 344; Casola and Baldaro, Reference Casola and Baldaro2021: 4). Paris allegedly used its influence in Niamey to make sure Italians would not deploy in the far north, a strategic area near the Libyan border where French troops were already stationed, but would ultimately be confined to the capital city. The tensions with France over the Sahel – following previous strains over Libya – criss-crossed with anti-jihadism cooperation between the two European countries.

On the economic front, competing for energy security was a potential driver too. Italy is the fourth most energy-dependent country in the EU, only surpassed by tiny Malta, Luxemburg and Cyprus in the extent to which it relies on imports to meet its energy needsFootnote 12. Renzi had emphatically pointed out that global geopolitical tensions and uncertainties required diversifying energy sources away from the East-West axis. Better developing South–North supplies via new economic and energy investments implied a vision of Africa that would move beyond development cooperationFootnote 13. In the process, ENI was openly singled out as a key component of Italy's policyFootnote 14. In practice, however, this had little impact on a company that has traditionally acted in an autonomous way – neither on the impulse of, nor as an impulse for, government strategyFootnote 15 – as testified by the fact that the expansion of the number of sub-Saharan countries the oil and gas giant operates in – from three to nine – had already taken place by 2012, that is, prior to the phase during which the Italian government focused its attention on the region.

Finally, a desire to improve Rome's international standing also seemed to make Italy more willing to emulate other countries or at least parts of their approaches to Africa. Renzi's yearning for recognition, for example, contributed to opening the way to the reform for the modernization of development cooperation, driven by its normative meaning as a response to long-standing international criticisms – at times a veritable ‘name and shame’ campaign – and pressures to meet existing standards. An expanded aid budget, in particular, was also meant to help advance Italy's image as a more reliable and effective foreign policy actor. Even the eventual decision to condense and formalize the national approach to Africa in a single identifiable policy document – the Partenariato – was possibly driven not only as a means to an end, but by the aim of gaining legitimacy by aligning to recently emerged practices too.

Italy's Africa policy was thus affected by policy elements and initiatives that had been earlier introduced in other countries. Yet diffusion dynamics appeared to be relatively limited and only weakly connected to policy developments. Rather, the numerous measures targeting Africa that Italy introduced – as reconstructed in the previous sections of this paper – strongly suggest that something different and much more relevant was at play which accounts for the country's unexpected activism.

Driving Italy

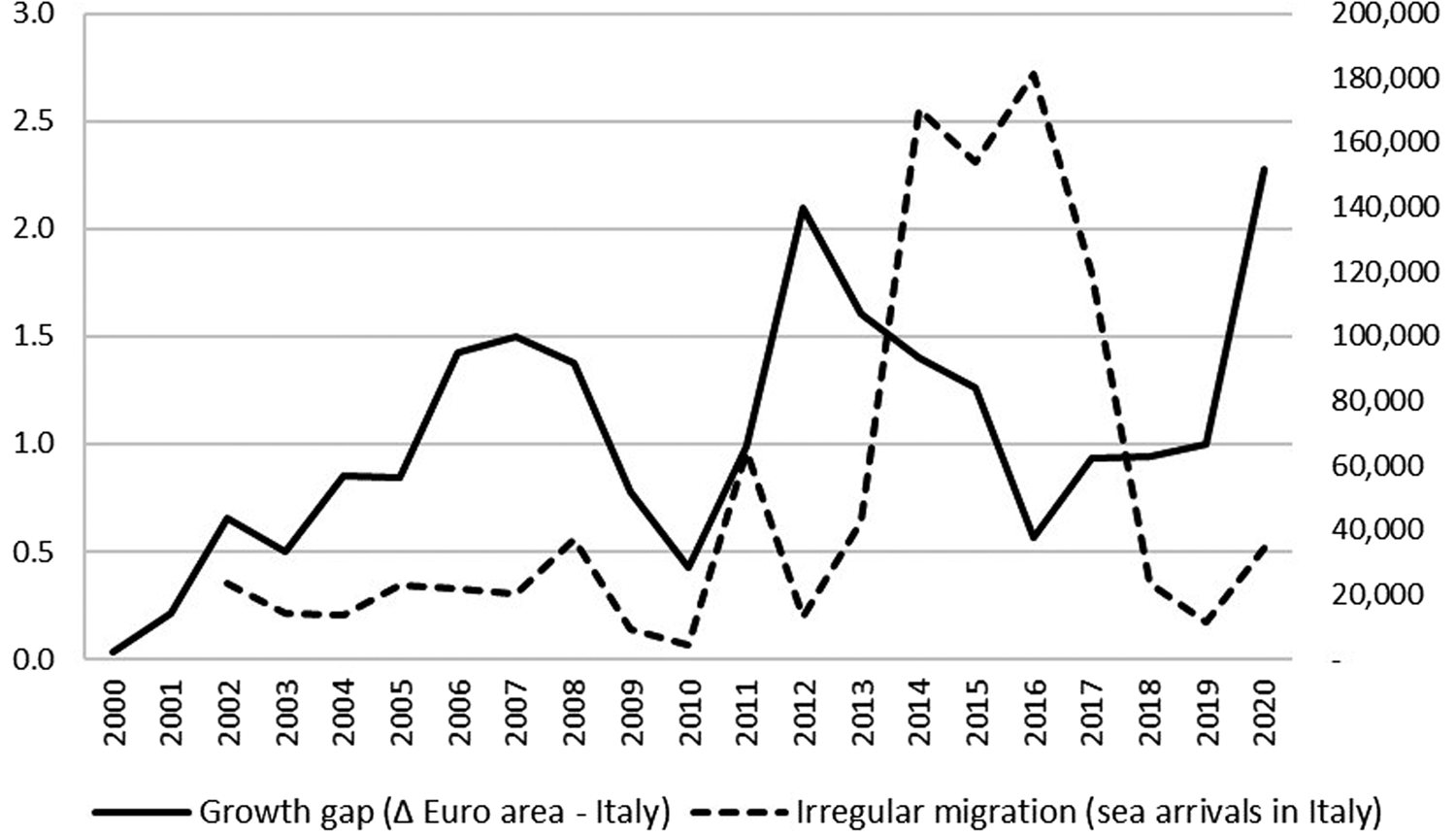

The late rediscovery of Africa by Italian decision-makers was reactive rather than anticipatory or proactive. As mentioned, two great stimuli came from successive emergencies the country had to face. First, Italy was the hardest hit in Europe by the economic recession induced by the global financial crisis and, almost immediately after that, prolonged by the European debt crisis (−1.0% average annual growth in 2008–2014, the second lowest in the Euro areaFootnote 16). Then, on a different front, Rome was most directly affected by the so-called ‘migrant crisis’ (with the largest number of irregular arrivals in Europe after Greece in 2014–2017, the largest by sea and the largest for a single year in 2014, 2016 and 2017). Data in Figure 2 show that the gap between economic growth performances in Italy and in the Euro area peaked in 2012–2013, whereas a massive increase in irregular migration took place over the subsequent 2014–2016 period. The exact timing of these events helps explain their sequential impact on policy-making. As recovering the economy and managing migration became ever more pressing domestic issues, two solutions were elaborated – summed up, respectively, by the ‘diplomacy of growth’ and the ‘help them in their home countries’ refrains – which both led to stepping up Italy's Africa projection.

Figure 2. Economic growth and irregular migration in Italy.

Note: ‘Growth gap’ (left-hand axis) shows the difference between GDP growth (annual percentage change) in the Euro area and in Italy. Data for irregular migrants refer to the right-hand axis.

Sources: IMF World Economic Outlook database and Italian Ministry of Internal Affairs.

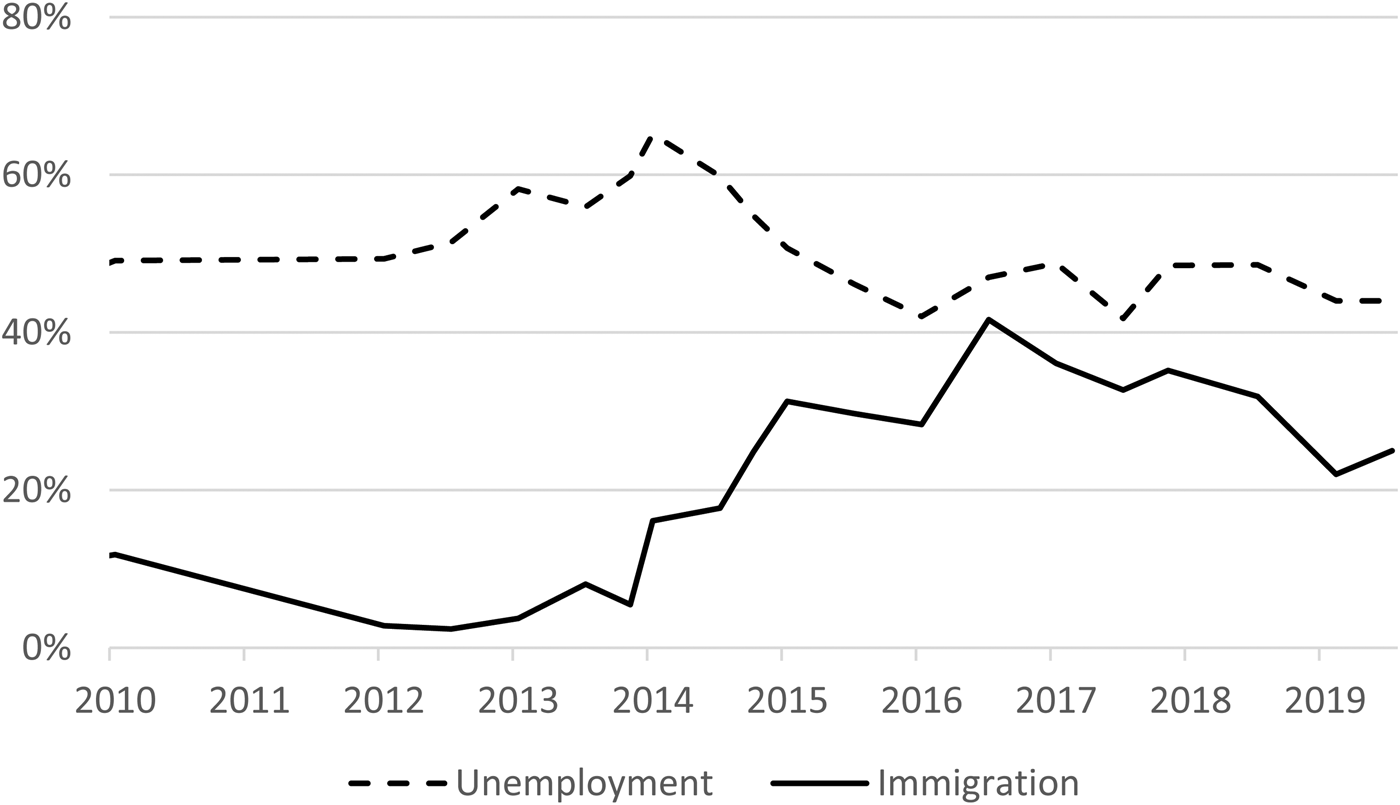

The trends in public opinion with regard to the issues of ‘economic security’ and ‘fear of immigration’ (Figure 3) reveal the extent to which Italians were concerned with the former peaked in 2013 and then stabilized at lower levels (at least until the pandemic struck), seemingly leaving room for anxieties about immigration to rise until they themselves climaxed in 2018. Similarly, the share of those who included unemployment when asked ‘What do you think are the two most important issues facing Italy at the moment?’ doubled between 2008 and 2013 (up from 29 to 56%) and peaked in mid-2014 at 65% (Figure 4). The share of those pointing at immigration went through a sixfold increase from 7% in 2008 to a peak of 40% in 2016. Italians thus appeared to be anxious about both issues, and demanded political action.

Figure 3. Public opinion and security in Italy: the economy and immigration.

Notes: Economic insecurity: % who say they are ‘frequently’ worried by at least one of four issues: money for living expenses, pension, unemployment, savings.

Fear of immigration: % who say they ‘agree’/‘agree a lot’ with the statement ‘Immigrants are a threat to public order and to the security of people’.

The data points for 2013 are actually based on a December 2012 survey; the 2018 data for economic insecurity are missing.

Sources: Osservatorio Europeo sulla Sicurezza, Demos & Pi survey for Fondazione Unipolis, May 2020, April 2021 and September 2021.

Figure 4. Public opinion and key political issues in Italy: unemployment and immigration.

Notes: % who chose unemployment/immigration when asked ‘What do you think are the two most important issues facing Italy at the moment?’.

Sources: Eurobarometer.

Elected representatives were receptive of the ups and downs in public opinion's concerns with regard to these matters (with some politicians typically fuelling them too). In a content analysis of parliamentary debates, the combined frequency of the terms ‘economic crisis’, ‘economic recovery’ and ‘economic growth’, for example, jumped from 84 in 2007 to an annual average of 261 in 2009–2014, that is, it more than tripled, before dropping regularly over subsequent years. The recurrence of the words ‘immigration’ and ‘immigrants’, on the other hand, remained subdued during 2012–2013 – the lowest and second-lowest years in two decades – but a spike followed in 2014, at the outset of the migrant crisisFootnote 17.

In the search for ways out of the 2011–2013 economic downturn, which heavily dampened domestic demand and consumption, and of the related concerns, finding new markets for Italy's exports and investments became ever more of a priority. Moreover, widespread cuts to public spending raised pressures on the foreign service to justify its raison d’être by demonstrating its usefulness and contribution at a critical time for the country's recovery. The ‘diplomacy of growth’ thus became a new mantra emanating from the Farnesina palace, home to the foreign ministry, and targeting Italy's myriad small and medium enterprises and their internationalizationFootnote 18. Both official and unofficial documents show that the ministry of foreign affairs itself – traditionally only partly involved in this area – gradually made support for Italian trade and investments one of its main tasksFootnote 19. The Farnesina aimed ‘to play an increasingly dynamic role to favour growth processes of the national economy … to seek and seize new opportunities in global markets … and to promote the interests of our companies to favour their internationalization’Footnote 20.

When seeking where to orient economic diplomacy efforts, the ‘Africa rising’ narrative, alongside its proximity and historical links, helped the region enter the radar as an attractive option: since around 2000 sub-Saharan Africa had experienced a period of unprecedented economic growth, reversing the disappointing trends that had prevailed in the 1980s and early 1990s. With expanding business opportunities in the continent's fast-growing frontier markets, benefits were now balancing risks and Italy sought to position itself as an economic ‘gateway to Africa’Footnote 21. Ultimately, the ‘diplomacy for growth’ was thus explicitly cited both as a ‘political priority’ and a reason to ‘expand Italy's attention towards Africa’, itself deemed a ‘strategic goal’ of Rome's foreign policyFootnote 22.

The flurry of initiatives adopted during 2013–2018 – and their partial continuation in 2019–2020 – however, gradually went through a crucial change of emphasis and focus: from growth diplomacy, high on the agenda during a first phase under the governments led by Enrico Letta and then by Matteo Renzi, to a much-increased relevance given to the management and containment of migration flows originating south of the Sahara. An analysis of Prime ministers' investiture vote speeches shows that the terms migration and immigrants were not specifically mentioned in the programmes outlined by Prime ministers Mario Monti (2011), Enrico Letta (2013) and Matteo Renzi (February 2014), but after 2014 these terms gained the attention of Paolo Gentiloni (2016), Giuseppe Conte I (2018) – backed by populists and sovereignists, the incoming Prime minister used them twice as many times as in any of the other speeches considered – Conte II (2019), and, if only slightly less, Mario Draghi (2021)Footnote 23.

With migration taking over as the key priority, the perception of mounting risks coming from the continent partly overshadowed the opportunities that had been at the core of the ‘Africa rising’ optimism. But political stakes and pressures had grown too, and the focus on the region had to be retained. The migration wave of the mid-2010s was more ‘African’ (and more, precisely, more sub-Saharan) than had been the case with previous waves: the stock of sub-Saharan immigrants in Italy surged from 270,000 in 2012 to 454,000 in 2019, that is, a 68% increase, as against a much more limited 20% upturn for the country's non-sub-Saharan immigrant populationFootnote 24.

Thus, while the narrative swung towards the perceived threats emerging from Africa, it led not only to the idea of erecting barriers but also to the notion of ‘helping them in their home countries’ – so to address the ‘root causes’ of migration – that is, a perspective that still implied the continent could not be neglected. A motion adopted by parliament in mid-2015 illustrates how the migration issue was used to commit the government to ‘a strategy specifically aimed at the development and co-development of African countries, starting with the countries of origin of the main migratory flows to Italy’Footnote 25.

Pressed to act, Rome had initially begun rethinking its approach to the Horn of Africa, traditionally a privileged area, due to the large numbers of immigrants hailing from Eritrea (the vice-minister for foreign affairs had made a rare visit in 2014), Somalia (the minister for foreign affairs had co-chaired the IGAD Partners Forum for Somalia in 2013) and Ethiopia. But the Sahel, as pointed out, was increasingly stealing the scene as a major and turbulent transit zone for migration that raised growing concerns. It quickly came to ‘represent the central priority of [Italy] in sub-Saharan Africa’ (Mistretta, Reference Mistretta2021: 125), with new embassies opened across the area and a string of bilateral defence agreements signed with Chad, Niger, Burkina Faso and Mali between 2017 and 2021. The region was now deemed part of a so-called ‘Enlarged Mediterranean’, a sloppy and unfortunate expression referring to an area spanning from the Great Middle East, through the Horn of Africa, to the Sahel. This geopolitical notion implied adjusting the third of the three pillars of Italy's post-WWII foreign policy (namely, Atlanticism, Europeanism and the Mediterranean) to allow sub-Saharan Africa, which had hitherto remained marginal, enter the frame. A historic change for Italy's foreign policy.

The focus on migration, a topic which had already been high on Italy's agenda over the years, peaked during the short spell in which the populist right joined a new coalition government, following the 2018 national election. Rome's strong prioritization of the subject was visible in Prime Minister Conte's two sequential visits south of the Sahara – first to the Horn and then to the Sahel – in the space of just four months. During his second trip, a bilateral military training initiative called MISIN (Missione bilaterale di supporto nella Repubblica del Niger) was launched for the training of Nigerien security forces and other personnel working to combat illegal trafficking in the Agadez region.

On the face of it, the need to ensure security by responding to the threats posed by violent extremism in a relatively nearby region was also part of the picture. Addressing terrorism and irregular migration were officially presented as joint motives for a strategic shift in Italy's foreign and defence policy posture, with the acknowledgement of Africa's new centrality – and, notably, the Sahel – a reduced emphasis on Middle Eastern theatres, and a relocation of troops from the latter to the former area. The two were deemed reasons for investing in building up African actors' capacity to better control their territories. The mandate of the bilateral military mission in Niger referred to the fight against illegal trafficking and security threats in a very broad, generic mannerFootnote 26. Yet for the Niger operation, terrorism hardly actually entered the political and parliamentary debate and, when it did, it was largely as a secondary concern related to irregular immigration itself, as data in Ceccorulli and Coticchia (Reference Ceccorulli and Coticchia2020) reveal. By the time the mission was actually deployed, in late 2018, the defence minister simply referred to ‘the mission in Niger for the control of migration flows’Footnote 27, both an ‘unprecedented’ objective for a military mission (Strazzari and Grandi, Reference Strazzari and Grandi2019: 348) and a clear illustration of the primacy of domestic factors in driving Italy's Africa policy. Ultimately, responding to terrorist threats can be ruled out as a motive for Italian engagement in the region (Ceccorulli and Coticchia, Reference Ceccorulli and Coticchia2020: 192).

The migration priority came to shape other government actions too. It increasingly had a bearing on development policy, for example (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2020a). An integrated approach was adopted that, in addressing ‘the structural causes of forced migration’, framed development and security as strictly interrelated dimensions. Geographically, Sahelian countries became a key focus of attention. Even relations with Brussels were deeply affected, as successive Italian executives insisted on an EU-wide approach to migration management. Due to a geographic location making the peninsula ‘the first port-of-call for many refugees reaching Europe by sea’Footnote 28, Italy is the frontier country most exposed to the Mediterranean routes. In 2016, the government thus advanced a proposal for a ‘migration compact’ targeting origin and transit countries in Africa that fed directly into a new Migration Partnership Framework launched by the EU that same year.

A narrow set of key policymakers

Africa thus climbed Italy's foreign policy agenda at a time when, during the 2013–2018 legislature, successive coalition governments with a predominant centre-left component led some energetic decision-makers grasp the opportunity offered by a favourable external environment and by the pressures national executives faced.

The notions of ‘diplomacy of growth’ and ‘let's help them in their home countries’ were a manifestation of how popular sentiments entered the discourse of key political actors and contributed to setting political and government prioritiesFootnote 29. The two mantras sum up the connection between popular demands and the search for political responses. An array of specific new policy measures were thus presented by Italian governments as direct and necessary responses to the abovementioned two drivers: top level diplomatic trips, the opening of new embassies, the expansion of aid volumes and the organization of Italy–Africa conferences, for example, were all explicitly aimed at opening new market opportunities for Italian businesses as well as at cooperating with countries of origin and transit in order to gain leverage in the management of migration flows.

The recovery of economic growth had featured prominently in the Democratic Party-led coalition programme for the 2013 election – as measured by the occurrence of the terms ‘growth’, ‘crisis’ and ‘recovery’ – both when compared to those of other political forces as when compared to the PD programme of 2008. Moreover, a content analysis of parliamentary speeches reveals a marked and stable increase over the years in the frequency Africa was mentioned by MPs in the lower house of parliament (Camera dei Deputati), which more than doubled from a 52 times annual average in the 2001–2006 legislature to over 104 in the 2013–2018 one. The surge started in 2009, reached a high point in 2011 due to the Arab Spring (but also at a time of growing economic interest) and then a major peak in 2014–2015, during the migration crisisFootnote 30. While a few parliamentarians were directly involved in re-making the Africa policy, however, parliament as such was largely by-passed by a policy process that was primarily driven by the executive (the main, partial exception being the reform of the development aid system).

Beginning with the first, short-lived grand-coalition government of 2013, led by Enrico Letta and inclusive of Silvio Berlusconi's centre-right People of Freedom party, it was a comparatively small network of very active second-tier politicians hailing from to the centre-left PD that paved the way. They held crucial positions at the Ministry of foreign affairs (vice minister for foreign affairs Lapo Pistelli, undersecretary of state for foreign affairs Mario Giro) and in the parliamentary committee on foreign affairs of the Camera dei Deputati (committee secretary Lia Quartapelle), and gained substantial backing from Renzi, a brisk leader and forceful prime minister that at the time enjoyed strong political supportFootnote 31.

These elected politicians, sustained by their leader and their party, were initially acting somewhat autonomously, rather than reacting to specific external demands, but the latter increased as finding ways of addressing migration became a paramount popular concern. The same political figures subsequently sped up the process and expanded it. In a highly telling and symbolic move, they even tabled a bill dubbed ‘the Africa Act’ in the lower houseFootnote 32. It was these individuals that ultimately proved decisive in reshaping Italy's Africa policy.

While the five foreign ministers that alternated at the head of the Farnesina in 2013–2020 (namely, Emma Bonino, Gentiloni and Luigi Di Maio, less so Angelino Alfano and Enzo Moavero Milanesi) played a supportive role at most, it was thus other actors within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that, all along, took the lead. Direct pressure was brought to bear on bureaucrats at the Ministry – notably, the top diplomats in charge of the General Directorate for Globalization and World Affairs – who were largely won over due to their need to legitimize the diplomatic service as a valuable resource at a time of wide-ranging budget cuts and, in the case of the reform of the aid sector, to the fear they might lose control over development policy (and related resources) had they not jumped on boardFootnote 33. At subsequent stages, the Director for sub-Saharan Africa was credited with feeding most contents into the Partenariato. Beyond the MFA, vice-minister and later minister for economic development Carlo Calenda also chipped in with regard to the implementation of the diplomacy of growth approach.

Party politics and interest groups were thus essentially circumvented, particularly in the early phases of the new course, when the economic rationale for turning to Africa played a major role. Inter-party competition gradually acquired more salience as addressing migration more squarely was deemed necessary to contain the ability of centre-right political actors to capitalize on the issue. Italy's formal proposal that the EU adopted a Migration Compact went in this direction.

Overall, however, the number of decision-makers that had a role in redesigning Italy's approach to the sub-Saharan region remained relatively narrow, with limited public debate and, with few exceptions, marginal contributions only for political parties, MPs, NGOs and the business community. The ideological stances of a few decision-makers helped frame and select the issues, including the external policy lessons they would use.

End of a season?

With the election of a new parliament, in 2018, a page was turned. As mentioned, however, migration continued to overshadow topics such as business opportunities or additional security issues and partly also swallowed up development cooperation into Italy's foreign policy agenda for Africa. Migration topped the agenda of the League party and somewhat of the Five Star Movement too, and the government they installed under Conte's leadership went on to implement some of the measures targeting Africa that had been introduced previously, including important actions in the Sahel. At the MFA, in particular, vice-minister Del Re of the Five Star Movement offered some continuity in terms of engagement in the latter region. Despite the ‘helping them in their home countries’ mantra might have offered reasons and room for strengthening bilateral cooperation with key African countries, however, the League party in practice dragged its feet. Aid to Africa went down, with minor development projects only initiated with Ethiopia and Burkina FasoFootnote 34. No new bilateral agreements with African countries of origin and transit were signed, not even for the readmission of migrantsFootnote 35; rather, undue pressures over repatriations led to critical reactions by some African partners (Strazzari and Grandi, Reference Strazzari and Grandi2019: 342).

The partial slowdown of the continent's economic dynamism that had started with the fall of key commodity prices, a few years earlier, and had sucked oxygen away from the ‘emerging Africa’ storylineFootnote 36 as well as from the ‘diplomacy of growth’ rhetoric, was compounded by the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020–2021. The latter constrained Italy's public planning and action as much as sub-Saharan migration flows, and contributed to freezing attention towards the region – at least until the war in Ukraine sparked a rush to ensure an expanded provision of gas from African producers.

The extent to which Italy's government – rather than just the foreign ministry with the occasional backing of a Prime Minister – is and will stay committed to Africa and to the recent plan for the continent remains an open question. Even more so given Italy's unresolved and highly consequential problem of chronic government instability. The historically frequent stops-and-goes in government and ministerial composition typically raise the chances that new policies, acts or courses of action are rapidly abandoned, reversed or simply forgotten, hardly a favourable element for building a more consistent and lasting approach towards a region – that is, sub-Saharan Africa – that increasingly requires one.

Conclusions

A southern European country with a peculiar geographical exposure, in recent years Italy moved out of a long period of substantial neglect of the sub-Saharan region by looking at the area with new eyes, interests and needs. This in turn prompted Rome to both devise its own new tools and strategies to approach the region, while also increasing its involvement in EU initiatives.

This paper examined the plausibility of the policy diffusion hypothesis in accounting for Italy's change of approach. The explicatory potential of this explanation, however, is ultimately downplayed by showing how the core mechanisms it is based upon were only marginally at work. Rather, an alternative causal pathway is proposed that originated from essentially domestic drivers and, via a complex chain of intermediate stages and supplementary influences, as outlined in Figure 1, produced the innovation of Italy's Africa policy as an outcome. The two crucial factors that led to a substantial change of approach and pace in Rome's attitude towards Africa were the tough impact of the European debt crisis of 2011–13 and later the migrant crisis of 2014–2016. Ultimately, Italy followed a direction similar to that of other countries, and yet its actions were primarily sparked and motivated by two clear-cut reactive, autonomous, domestic drivers. The kind of international interdependence that underlies diffusion processes proved to have very limited traction when empirically assessed and contrasted with country-specific, (quasi-)independent motives.

The explanation offered in the paper is corroborated by empirical substantiation from multiple types of sources – from semi-structured interviews, official documentation and parliamentary records, to public opinion surveys, economic and migration statistics, and web analytics – all relevant to the main argument while also providing more specific support to each of its different components. The very convergence of manifold and diverse evidence backing the argument constitutes good ground for being reasonably confident in it.

The diffusion hypothesis remains a plausible explanation for other European cases. Yet the present analysis expands the range of potential factors accounting for the recent proliferation of Africa policies adopted by EU countries. While no broad generalizations are possible, this investigation provides conceptual and empirical insights that may prove helpful for future research in a larger and diverse population of cases.

Funding

The research received no grants from public, commercial or non-profit funding agency.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp.