Introduction

When the five presidentsFootnote 1 of the European Union (EU) institutions convened in 2015 to agree upon a roadmap for the next steps towards the completion of European economic and monetary union (EMU), they proposed the creation of an advisory European Fiscal Board (EFB). Why did the five presidents concur to create yet another highly specialized expert body? The euro area crisis had led to a surge in new intergovernmental institutions like the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), whose purpose was to increase the EU's crisis resilience. Yet, policymakers felt that the design flaws of the fiscal governance framework had not been sufficiently addressed despite the six- and two-pack reforms. The compliance rate with the European fiscal rules remained chronically low and the European Commission's alleged forbearance towards fiscal profligacy was not well received in some member states. As a result, these developments warranted the creation of a ‘watchdog for another watchdog’ (Asatryan et al., Reference Asatryan, Debrun, Heinemann, Horvath, Ódor and Yeter2017).

Since 2013, EU member states were legally obliged to create a ‘functionally autonomous’ fiscal council at the national level (Fromage, Reference Fromage, de Witte, Kilpatrick and Beukers2017; Jankovics and Sherwood, Reference Jankovics and Sherwood2017; Jankovics, Reference Jankovics, Piroska and Rosta2020). A fiscal council is ‘a permanent agency with a statutory or executive mandate to assess publicly and independently from partisan influence government's fiscal policies, plans and performance’ (Debrun et al., Reference Debrun, Kinda, Curristine, Eyraud, Harris, Seiwald and Cottarelli2013: 8). In the euro area, national fiscal councils are tasked with the monitoring of the national fiscal rule framework and the assessment of macroeconomic and/or budgetary forecasts of the government to reduce incentives to publish overoptimistic forecasts. As national fiscal councils started to exchange best practices, the incentives to create a similar European watchdog to coordinate them grew for the Commission. To avoid the ‘cacophony of voices problem’, that is, that each fiscal council interprets the fiscal rules in its own way, a minimum degree of coordination was required (Debrun, Reference Debrun2019). From the Commission's perspective, it was beneficial to have national allies when confronting individual non-compliant member states.

The advisory EFB was created by Commission decision 2015/1937 in October 2015.Footnote 2 It became fully operational in October 2016 when the EFB chair – the renowned Danish economist and former member of the Delors committee Niels Thygesen – and four other board members were formally appointed. The Commission took the lead in drafting the EFB's mandate largely bypassing the member states. As a result, the final mandate differed substantially from the guiding principles of the five presidents. This attracted criticism from Germany and the Netherlands that had clear preferences for the design of the EFB (Steinhauser, Reference Steinhauser2015). The EFB produces an annual report published in autumn and an assessment of the prospective euro area fiscal stance each summer feeding into the annual budgetary cycle of the European Semester. According to its mandate, the EFB also provides ad-hoc advice to the Commission President upon request. In 2019, Commission President Juncker requested the EFB for the first time to produce an ad-hoc assessment of the six- and two-pack reforms (European Fiscal Board, 2019b). From an EU integration theory perspective, the EFB challenges common assumptions in the literature about the types of institutions that are created and who stand to benefit from them. Thus, this paper contributes to our understanding of the theoretical underpinnings of the institutional design features of the EFB.

The following section describes the creation of the EFB from an EU integration theory perspective. It asks whether the EFB conforms to the theoretical expectations of the new intergovernmentalism or orchestration theory (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal, Zangl, Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2015a, Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2019; Bickerton et al., Reference Bickerton, Hodson, Puetter, Bickerton, Hodson and Puetter2015a, Reference Bickerton, Hodson and Puetter2015b). It empirically assesses the level of independence of the EFB. The second section gives an overview of the EFB's mandate and compares it to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development's (OECD) design principles for fiscal councils. The paper concurs with Scipioni (Reference Scipioni2018) that de novo bodies do not necessarily have to erode the Commission's authority. In sum, the paper concludes that the EFB is neither a fully-fledged EU agency nor an intergovernmental body, but rather a semi-autonomous advisory body enlisting independent experts to promote the Commission's agenda.

Theory: new intergovernmentalism and orchestration

For scholars of European integration, the creation of the EFB provides a test case for one of the central hypotheses of the new intergovernmentalism theory. The new intergovernmentalists' claim that competences that traditionally would have been delegated to the European Commission are instead transferred to de novo bodies like the ESM ‘that often enjoy considerable autonomy by way of executive or legislative power and have a degree of control over their own resources’ (Bickerton et al., Reference Bickerton, Hodson, Puetter, Bickerton, Hodson and Puetter2015a: 705). According to Hodson (Reference Hodson2019: 15), the EFB constitutes an example of a de novo body. Schimmelfennig (Reference Schimmelfennig2015: 724) pointed out that ‘“de novo bodies” display a wide variation of intergovernmental and supranational features’. He argued that the delegation of new competences to highly autonomous supranational institutions like the European Central Bank (ECB) contradicts the claims of the new intergovernmentalists. Although Schimmelfennig's critique cannot be easily dismissed, it is important to highlight that in the case of the EFB some member states also preferred a stand-alone supranational de novo fiscal watchdog to the Commission out of distrust. Yet, the Commission managed to counter these forces through an institutional design that leaves the EFB financially dependent on the Commission's resources. In fact, it is the changed trend in the motivation for delegation on which Schimmelfennig (Reference Schimmelfennig2015: 724) concurs with the new intergovernmentalists, namely, that ‘governments have been reluctant to empower the Commission in the policy areas integrated since Maastricht’.

The analysis departs from the assumption that the Commission perceives the new intergovernmental dynamics as a challenge to its own authority. Member states increasingly promote de novo bodies that are beyond the Commission's immediate control. To counter this trend, the Commission can set up supranational de novo bodies that are dependent on its material resources. In addition, these bodies depend on their supranational principal for operational support and access to information. The Commission tries to compensate the lack of independence by enlisting external reputable policy experts. The EFB, for example, consists of board members with diverse professional backgrounds and impeccable fiscal policy credentials.Footnote 3 By enlisting independent experts, the Commission can bolster its authority in the realm of fiscal matters. The central rationale behind this pre-emptive strategy is to deflect member states' desire to delegate competences away from the Commission towards other bodies outside its control. In the case of the EFB, the logic of setting up a supranational de novo body differs from its intergovernmental counterparts insofar as the Commission was largely able to determine its design features rather than the member states.

Tesche (Reference Tesche2020) argued that the EFB should be conceptualized as an orchestrator because it lacks hard executive or legislative powers and depends on the Commission for its own resources. Orchestrators compensate for their capability deficits by enlisting the existing authority of intermediaries (the national fiscal councils) to govern policy choices indirectly (see Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2015b). Orchestrators and intermediaries share certain governance goals (for instance, stronger compliance with fiscal rules) and therefore the intermediary might be willing to cooperate with the orchestrator on a voluntary non-hierarchical basis (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2019). However, this leaves the orchestrator with little means to control the intermediary's actions. Consequently, the orchestrator can only offer soft incentives such as ideational support and persuasion to convince the intermediary (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Genschel, Snidal and Zangl2015b: 722). The hard ex ante and ex post controls inherent to conventional principal–agent relationships are not available to the orchestrator. This is a major shortcoming of this type of cooperation and makes it vulnerable to defection of the intermediary. As the subsequent sections will show, national fiscal councils have expressed reservations about their cooperation with the EFB because they were concerned about undermining their own independence. Given that some national fiscal councils possess superior material and ideational resources compared to the EFB, the prospects for the EFB to orchestrate national fiscal councils remain slim. However, it cannot be excluded that the picture will reverse in the future. It is possible that national fiscal councils could face increasing budget cuts from their governments and might have to rely instead on material and ideational resources from the Commission.

To assess what the defining features of the EFB as a supranational de novo body are, the analysis focuses on the EFB's independence as the key variable. Drawing on the experience of intergovernmental de novo bodies like the ESM, we would expect the EFB to be highly independent in terms of material resources but dependent on member states in terms of decision-making. However, this is not the case and warrants further scholarly scrutiny. The next section will introduce the EFB's mandate and provide an assessment of its functioning as a supranational fiscal council using the OECD's principles.

The European Fiscal Board: mandate and functioning of a supranational fiscal council

The creation of the EFB responded to the criticism of fiscally-hawkish creditor countries like Germany and the Netherlands that lamented the Commission's reluctance to enforce the fiscal rules (Steinhauser, Reference Steinhauser2015). The underlying idea was that an independent fiscal council at the European level would re-establish the lost credibility of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) by closely monitoring how the Commission performed its job as assessor of member states' fiscal policies. The part of the mandate that tasked the EFB with monitoring the growth-friendly composition of the individual national fiscal stances at the aggregate euro area level was aimed at ‘countering concerns from fiscal doves such as Italy that it was yet another instrument to impose austerity’ (Steinhauser, Reference Steinhauser2015). In this regard, the EFB mandate reflected a carefully crafted compromise that enabled both creditor and debtor countries to support its creation.

Against this backdrop, the five presidents outlined three objectives that the new European advisory body should achieve: (i) ‘lead to better compliance with the common fiscal rules’, (ii) ‘a more informed public debate’, and (iii) ‘stronger coordination of national fiscal policies’ (Juncker et al., Reference Juncker, Tusk, Dijsselbloem, Draghi and Schulz2015: 14). For this purpose, the five presidents' report laid out a number of guiding principles for the mandate of the EFB. The first principle was that the advisory EFB ‘should coordinate the network of national fiscal councils and conform to the same standards of independence’ (Juncker et al., Reference Juncker, Tusk, Dijsselbloem, Draghi and Schulz2015, annex 3). Although the Commission would remain in the driving seat when it comes to the enforcement of the fiscal rules, it should explain its reasons if it were to deviate from the advice given by the EFB (‘comply-or-explain’ rule). Another key part of the EFB's mandate was to apply economic judgement about the appropriate fiscal stance for the euro area as a whole in full respect of the EU fiscal governance framework. According to the five presidents' report, the EFB should intervene by issuing opinions on the assessment of the stability programmes and the presentation of the annual draft budgetary plans and the execution of the national budgets. Finally, it should also provide ex post evaluations regarding the implementation of the EU governance framework.

However, the former Dutch and German finance ministers had misgivings about the way in which the five presidents' guiding principles were implemented by the Commission. Jeroen Dijsselbloem – former Dutch finance minister and president of the Eurogroup – wanted the EFB to become a stand-alone institution detached from the Commission (in line with the intergovernmental de novo body). Such an institutional set-up would have enabled the EFB to assess member states' draft budgetary plans as an independent referee. Former German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble wanted to go beyond Dijsselbloem's proposal. He was adamant that all tasks requiring the Commission to use impartial judgement should be delegated to an independent stand-alone institution (Steinhauser, Reference Steinhauser2015). In a departure from the traditional community method, the Commission ultimately enshrined the EFB's mandate in a Commission decision that member states could not veto. It was able to take the lead and bypass member states because the EFB only functions as an advisory body of the Commission that does not have any legislative powers and can only issue non-binding recommendations. Even if it can exert ideational influence on the fiscal policy discourse at the expert level with the publication of its annual report, a Commission decision was chosen as the appropriate legal instrument for the EFB's creation. This implied that member states would only be involved to a limited extent. Yet, the Commission took the member states' stated preferences into account. Another distinguishing feature of the EFB is that the Commission has a say on the appointment of the chair and the board members. This stands in contrast to stand-alone de novo bodies like the ESM and the ECB in which the appointment of the executive members is determined by the member states.

The final mandate reflects a lowest common denominator compromise between the preferences of the northern fiscally hawkish member states to enforce the fiscal rules more strictly and the southern member states' preference to receive more fiscal stimulus from member states with fiscal space. The latter objective is to be achieved through the EFB's task to assess the adequacy of the euro area fiscal stance, whereas the former objective is to be achieved through the EFB's task to monitor the implementation of the EU fiscal framework. This compromise between debtors and creditors is also mirrored in the geographical composition of the board members' nationalities (Denmark, Poland, Netherlands, France,Footnote 4 and Italy). The EFB's institutional set-up ran counter to the revealed preferences of some member states, but it enabled the Commission to exert control over the EFB. Thus, the Commission was able to counter the new intergovernmental dynamics by creating its own supranational de novo body.

The mandate of the EFB combines backward- and forward-looking analyses, that is, an ex post review of how the fiscal framework has performed in the previous year and an assessment of the prospective euro area fiscal stance for the next year. The assessment of the prospective euro area fiscal stance is usually published in June/July each year. It provides general guidance as part of the European Semester and offers a forward-looking perspective on the appropriate fiscal policy stance for the following year for the euro area and the national level. The optimal composition of the individual national fiscal stances might require a differentiation that could potentially conflict with the requirements of the SGP. The EFB annual report evaluates the overall functioning and implementation of the EU fiscal framework from an ex post perspective. This means that the annual report 2020 looks at the 2019 EU fiscal surveillance cycle. This limits its capacity to intervene in real-time to influence the course of events but prevents the creation of too much noise surrounding the fiscal surveillance process. Regular real-time interventions would increase the risk of conflicting assessments with the Commission and could put member states to ‘pick and choose’ the more favourable fiscal assessment (Debrun, Reference Debrun2019). However, it also curbs the EFB's ability to exercise its watchdog function over the European Commission. Any criticism that is made with the benefit of hindsight can be easily dismissed because real-time data at the time might have warranted a different approach. Wyplosz (Reference Wyplosz2019: 12) recalls how the EFB showed in its 2018 annual report that the Commission's recommended euro area fiscal policy stance in autumn 2016 turned out to be inappropriate after later data had shown that the economic recovery was stronger than expected. He concludes that fiscal policy coordination is desirable but might not be feasible due to the specific attributes of fiscal policy.

In addition, the EFB's mandate entails the cooperation with national fiscal councils. National fiscal councils are expected to foster compliance with national fiscal rules by communicating openly with national audiences. This can foster local ownership of the fiscal rules and enable voters to better judge the fiscal competence of their government (Beetsma and Debrun, Reference Beetsma, Debrun and Ódor2017). In some countries like the Netherlands, the national fiscal council is firmly anchored in the national fiscal framework and enjoys a high degree of legitimacy (Bos and Teulings, Reference Bos, Teulings and Kopits2013). To strengthen the position of the fiscal council vis-à-vis the government, a so-called ‘comply-or-explain’ rule is supposed to facilitate a dialogue in case of non-compliance. If the fiscal council observed a severe deviation from the planned fiscal path of the government, it should trigger a correction mechanism making fiscal profligacy more costly (Fromage, Reference Fromage, de Witte, Kilpatrick and Beukers2017: 113). However, most fiscal councils do not have the mandate to trigger a correction mechanism and where a ‘comply-or-explain’ rule has been institutionalized governments find ways to evade a meaningful explanation of their behaviour. These half-hearted provisions reflect member states' wavering commitment towards fiscal councils and their preference to remain unconstrained in their fiscal choices.

Overall, the tasks of the EFB differ from those that a national fiscal council traditionally undertakes (Asatryan and Heinemann, Reference Asatryan, Heinemann, Beetsma and Debrun2018). The EFB does neither enforce fiscal rules with regard to the SGP nor does it assess the Commission's macroeconomic forecasts. Instead, it acts as an advisor to the Commission. Yet, the EFB is vulnerable to the same threats faced by its national counterparts. First, the Commission could decide to limit access to information.Footnote 5 This would make it considerably harder for the EFB to monitor the Commission's role in the interpretation of EU fiscal rules and to assess the euro area fiscal stance. Second, the Commission could cut back the available resources that guarantee the EFB's operational support and decrease the size of the EFB secretariat. Such measures would further undermine the de facto independence of the EFB.

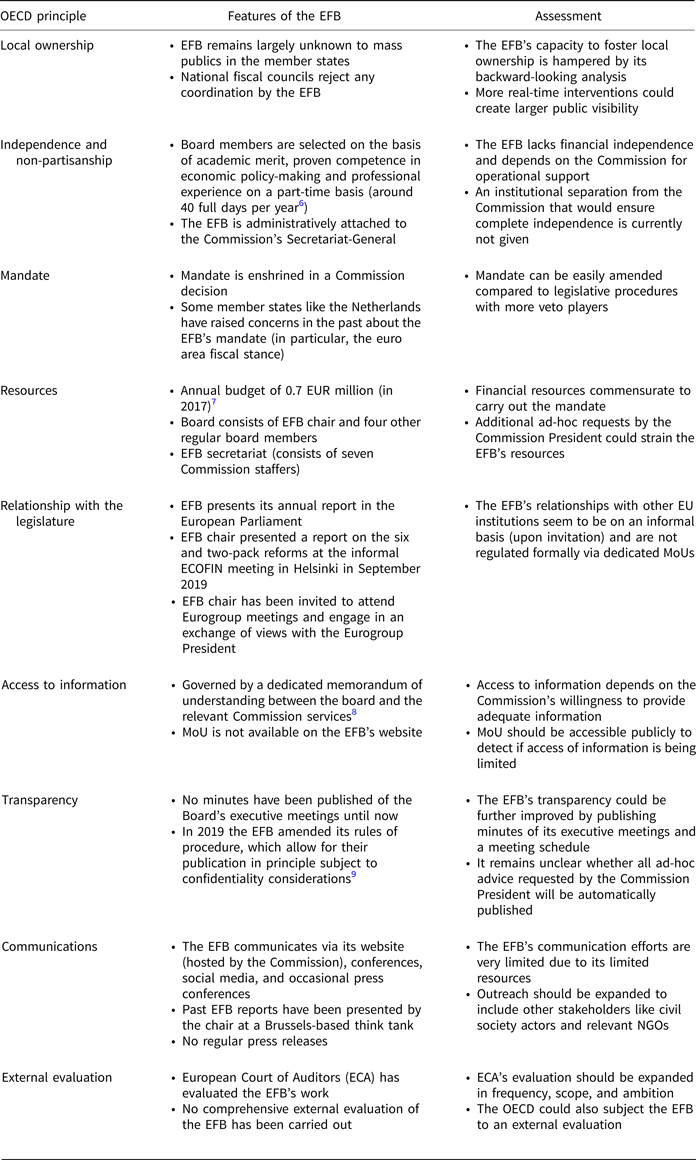

Various indices have been developed by different institutions (e.g. the Commission and the International Monetary Fund (IMF)) to measure and compare the independence and effectiveness of fiscal councils (Tesche, Reference Tesche2019; Closa Montero et al., Reference Closa Montero, De León and Losada Fraga2020: 29–36). However, these indices were often designed to promote a particular fiscal council model. A fiscal council index that is largely agnostic about the respective institutional set-up has been developed by the OECD. The OECD has been a vanguard when it comes to developing best practice regarding the design principles to make independent fiscal councils effective (OECD, 2014). Based on these principles, the OECD has carried out a number of external assessments of different national fiscal councils. The applicability of these principles to the case of the EFB is shown in Table 1, and the table suggests how the EFB's design features could be further improved. This helps us to better understand to what extent the theoretical classification of the EFB overlaps with the empirical evidence.

Table 1. OECD principles for independent fiscal institutions and the EFB

Source: OECD (2014) and own assessment.

The independence of the European Fiscal Board

From the very beginning there were concerns raised by the ECB and Germany that the EFB would not be sufficiently removed from the institutional structures to act truly independent of the Commission. The ECB and the IMF have both proposed that the institutional set-up of the EFB could be revised over time so that it would turn into a stand-alone institution (European Central Bank, 2015; IMF, 2016). Asatryan et al. (Reference Asatryan, Debrun, Heinemann, Horvath, Ódor and Yeter2017) considered the lack of operational independence a ‘major flaw’, which undermined the credibility of the new institution. The EFB's mandate is enshrined in a Commission decision, which can be amended as the Commission sees fit (Asatryan et al., Reference Asatryan, Debrun, Heinemann, Horvath, Ódor and Yeter2017; Tesche, Reference Tesche2020). This weak statutory independence and its scarce resources prevent the EFB from acting in a truly independent manner. A survey of the national fiscal councils conducted by the European Court of Auditors (2019: 29) found that a majority of 53% considered the EFB to have only ‘limited independence’, whereas 47% considered it to be ‘fully independent’.

The EFB relies predominantly on Commission staff to run its secretariat (Mijs, Reference Mijs2016; Asatryan and Heinemann, Reference Asatryan, Heinemann, Beetsma and Debrun2018: 169). The Board members are appointed by the Commission and are only employed on a part-time basis (European Court of Auditors, 2019: 27). Their mandate is relatively short (3 years) and can be renewed once. In April 2019, the Commission decided to renew the terms of the chair and the four board members for a second 3-year term, which started on 19 October 2019 (European Commission, 2019). This decision followed a consultation process involving the national fiscal councils, the ECB and the Eurogroup Working Group.Footnote 10 The EFB also lacks financial independence because its budget of 0.7 EUR million (2017) stems from the Commission, which is responsible for handling its human resources. ‘Its budget falls under the “Euro and Social Dialogue” budget of the cabinet of the Vice-President of the Commission and covers the salaries of the members (who have the status of special advisors) and the costs of their business trips. The Secretariat of the EFB is a unit of the Commission's Secretariat-General. As such, its expenses (business trips, invitation of experts, organisation of workshops, etc.) are covered by the operational budget of the Secretariat-General’ (European Court of Auditors, 2019: 28). If the Commission would decide to cut the EFB's budget, there would be no institutional safeguards in place to protect it. Although being nested inside the Commission services has the benefit of some limited access to information, a major drawback is the missing remoteness of the watchdog to its subject of oversight (Asatryan and Heinemann, Reference Asatryan, Heinemann, Beetsma and Debrun2018: 169). The chair of the EFB acknowledged that the EFB has to rely on the Commission's Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN) empirical work (Valero, Reference Valero2016). He stressed that many fiscal councils were facing a similar situation making them dependent on their finance ministries for some detailed calculations. However, this did not prevent them from forming independent views.

Yet, the fact that the EFB is hosted inside the Secretariat-General exposes it to potential conflicts of interests to the extent that the staff's future career paths depend on the Commission. For instance, the EFB has been a strong advocate of a centralized fiscal capacity in line with the Commission's long-standing preference (European Fiscal Board, 2017: 64–67). In its 2018 annual report it made a detailed reform proposal for the EU's fiscal framework (European Fiscal Board, 2018: 70–83). The EFB advocated for a medium-term debt ceiling of 60% of GDP, an operational debt reduction rule for member states with debt levels above 60% of GDP, a strengthened system of sanctions, one escape clause for exceptional circumstances and a streamlined fiscal surveillance cycle. According to the EFB, such a simplification of the fiscal framework would increase its effectiveness. Thus, its EMU governance reform proposals have followed an agenda that does not contradict the Commission's preferences for deepening EMU. The EFB has expanded its mandate by going beyond acting as a simple watchdog over the existing fiscal rules and their implementation. It has turned into an engine of institutional reform that actively pushes for a comprehensive reform of the fiscal framework.

Moreover, the EFB's mandate enables the Commission President to request ad-hoc advice from the EFB. The first ad-hoc request came in 2019 from the Commission President Juncker. He asked the EFB to review the six- and two-pack reforms just before the Commission's Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs was due to publish its own review, which was released in February 2020 and drew on the EFB's recommendations. The EFB's review of the EU fiscal framework was published in September 2019 (European Fiscal Board, 2019b). Its release put the Commission in the position to steer the debate about a potential reform of the EU fiscal framework because it elicited first responses from the member states. The EFB's review of the EU fiscal framework was presented to finance ministers during the informal ECOFIN meeting in Helsinki on 14–15 September 2019. A simplification of the complex fiscal rule framework was broadly supported by ministers but ‘there was a clear desire not to reopen a discussion on existing legislation’ (Codogno, Reference Codogno, Altomonte and Villafranca2019: 104). The French Finance Minister Le Maire cautioned against rewriting the SGP for fear of a ‘difficult, long and uncertain debate’ (Fleming and Khan, Reference Fleming and Khan2019). In sum, the debate helped the Commission to test the waters and to better understand the preferences of the different member states before launching its own consultation process on a potential reform of the EU fiscal framework. The episode shows how the Commission can coopt the EFB for its own agenda-setting by requesting ad-hoc advice on particularly salient topics. This is in line with the experience of national fiscal councils, which often bolster the negotiation position of their ministry of finance (von Hagen, Reference von Hagen, Beetsma and Debrun2018; Raudla et al., Reference Raudla, Bur and Keel2020; Raudla and Douglas, Reference Raudla and Douglas2021). Given the limited resources of the EFB any ad-hoc request by the Commission President will inevitably drain resources from its other main tasks to assess the euro area fiscal stance and the annual ex post review of the overall functioning of the fiscal framework. This could further undermine the limited independence of the EFB. Contrary to the guiding principles for the EFB's mandate laid down in the five presidents' report, there is no ‘comply-or-explain’ rule in place that would require the Commission to respond to any of the EFB's policy recommendations. The fact that the Commission can simply ignore the EFB's advice does not bolster its effectiveness. The institutional set-up of the EFB hampers its capacity to act as the ‘big European sister of the national fiscal councils’ as former Eurogroup President Dijsselbloem envisioned its role (Foy, Reference Foy2015). First, if the EFB does not conform to the best practice of how a fiscal council should be designed, it will be difficult to act as an enforcer of minimum standards for national fiscal councils. Second, as long as the EFB is perceived as an extended arm of the Commission, national fiscal councils will not trust any of the EFB's initiatives because it will always be suspected of attempted coordination. In sum, only a more independent institutional set-up will ensure that the EFB can take the lead in creating a European system of fiscal councils.

The EFB and national fiscal councils: between cooperation and coordination

This section assesses the prospects of the EFB coordinating the national fiscal councils. This evolving relationship is crucial to assess whether the EFB could turn into a supranational principal that controls the national fiscal councils in a hierarchical manner. Initially, the coordination of national fiscal councils was seen as one of the main activities of the EFB. The first-guiding principle in the annex of the five presidents' report clearly mentions that the EFB ‘should coordinate the network of national fiscal councils and conform to the same standard of independence’ (Juncker et al., Reference Juncker, Tusk, Dijsselbloem, Draghi and Schulz2015: 23). If the EFB together with the network of national fiscal councils would form a European system of fiscal councils, the EFB could function as the principal and the national fiscal councils as the agents similar to the European system of central banks (Asatryan et al., Reference Asatryan, Debrun, Heinemann, Horvath, Ódor and Yeter2017). However, the five presidents underestimated that many national fiscal councils had only recently been created and their institutional balance was not yet settled (Horvath, Reference Horvath2018). They were concerned that any coordination from the EFB would undermine their fragile independence and could be an obstacle towards the objective to foster national ownership of the fiscal rules (European Court of Auditors, 2019: 27). In addition, they were not convinced that the EFB would have been sufficiently independent of the Commission given that its secretariat is staffed with Commission officials (European Central Bank, 2015; Bundesbank, 2019: 79).

National fiscal councils gain their legitimacy in part from being impartial expert bodies that monitor the implementation of the national fiscal rules and/or European fiscal rules (Beetsma and Debrun, Reference Beetsma, Debrun and Ódor2017). Their concern was that if they were perceived by the public as another Brussels-based technocratic body, they would lose their credibility. The episode pointed to the difficulties that supranational actors can encounter when they try to harness national capacities. Cognizant of their limited capabilities the national fiscal councils have intensified the coordination efforts among themselves even though cooperation with the EFB could be mutually beneficial (Asatryan and Heinemann, Reference Asatryan, Heinemann, Beetsma and Debrun2018: 167). Instead of relying on guidance from Brussels they have started to exchange best practice in the Network of EU Independent Fiscal Institutions (EUIFIs) and to issue their own position papers on a wide range of topics pertaining to the role of fiscal councils in the EU fiscal framework. For example, the network of EUIFIs cautioned early on that ‘it is important to ensure that the EFB […] does not jeopardize the enforcement of the prevailing EU and national fiscal rules and the role of national IFIs in this regard’ (Network of EU Independent Fiscal Institutions, 2015). This strong rejection by the EUIFIs network of any coordination attempts was driven by their desire to establish their independent credentials.

However, as the initial insecurities were overcome the EUIFIs have mellowed their position on cooperation with the European level. First, national fiscal councils understood that if they wanted to maintain their independence in the long run, they needed to seek support from the supranational level. Examples of fiscal councils that openly criticized their government's non-compliance with national fiscal rules and subsequently became subject to budget cuts or received limited access to information were commonplace (Kopits, Reference Kopits2011; Kopits and Romhanyi, Reference Kopits, Romhanyi and Kopits2013). Second, the legal basis in the two-pack legislation for the creation of fiscal councils did not clearly define the minimum standards necessary for full institutional independence but only speaks of ‘functional autonomy’ (Fromage, Reference Fromage, de Witte, Kilpatrick and Beukers2017: 112). Such a weak legal basis cannot provide enough protection if a government actively tries to demolish its fiscal council. For this reason, the network of EUIFIs issued its own position paper on ‘defining and enforcing minimum standards for independent fiscal institutions’ (Network of EU Independent Fiscal Institutions, 2016). The EUIFIs network reiterated its opinion that it sees the EU provisions as too ambiguous and that fiscal councils remain highly vulnerable to budgets cuts. The network interpreted that fiscal councils would require an adequate level of resources, good and timely access to information, an effective ‘comply-or-explain’ principle anchored in national legislation and safeguards against domestic political pressures. Thus, it proposed a monitoring system, which could encompass periodic monitoring via country-specific recommendations in the European Semester and additional ad-hoc reporting by the Commission.

These developments point to a likely deepening of cooperation between the network of EUIFIs and the EFB. In 2019, the network announced that it would move its secretariat to Brussels where it would be hosted by the think tank Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS). At the same time, the EFB organized a dedicated workshop on ‘Independent Fiscal Institutions in the EU fiscal framework’ in February 2019 and answered the call of the EUIFI network by including a dedicated section on minimum standards for fiscal councils in its 2019 annual report (European Fiscal Board, 2019a). Debrun (Reference Debrun2019) has argued that coordination is necessary because it mitigates the ‘cacophony of voices’ problem that arises when national and supranational bodies monitor the same rules or assess the quality of macroeconomic and budgetary forecasts. In order to agree on a consistent interpretation of the fiscal rules and forecasting methodology more coordination is essential. Furthermore, he points out that coordination is required to achieve a degree of harmonization that ensures the effective functioning of fiscal councils in the euro area. A Commission draft directive from December 2017 that would have strengthened national fiscal councils has not been followed up on.

However, there are other obstacles that are likely to preclude deeper coordination. Currently, the Commission's DG ECFIN administers a frequently updated database on fiscal institutions based on a dedicated questionnaire. The EFB has also gathered data from IFIs through a dedicated questionnaire (European Fiscal Board, 2018: 42–51). However, the EFB's questionnaire falls behind the Commission's questionnaire in terms of scope and ambition. The Commission has also created a Scope Index of Fiscal Institutions, which measures the breadth of the tasks of fiscal councils. Furthermore, DG ECFIN has established a bi-annual meeting with the network of EUIFIs (Mijs, Reference Mijs2016; Jankovics and Sherwood, Reference Jankovics and Sherwood2017: 18). In sum, the Commission has arguably more developed ties to the national fiscal councils compared to the EFB. If the EFB should function as the main coordinator of the national fiscal councils, then it would not only need more resources, but also more timely access to information about how the Commission implements the fiscal rules. In view of the strong silo mentality within the Commission that pits different directorates against each other, it is unlikely that the EFB will deepen the relationship with the network of EUIFIs.

Thus far, the EFB's annual report included a dedicated chapter on the national councils. The chapter usually entails portraits of two selected European fiscal councils and a discussion of a horizontal topic such as an overview of different access to information regimes (European Fiscal Board, 2018). These portraits have focused on vanguard fiscal councils that tend to be regarded as relatively effective. As a result, the fiscal council portraits have remained factual and did not offer recommendations on how to reform them. Moreover, the EFB reviews the role of certain national fiscal councils in the EU fiscal framework by sending out a dedicated questionnaire to selected fiscal councils. In addition, fiscal councils that are mandated to monitor compliance exclusively with national fiscal rules can work diligently but its government might nevertheless be at risk of non-compliance because EU and national fiscal rules can differ substantially. Compliance with EU fiscal rules does not necessarily entail compliance with national fiscal rules. In member states like Italy, Spain, or Portugal, there are particularly strong fiscal councils in place (Horvath, Reference Horvath2018). Thus, to lower the administrative burden on national fiscal councils, the EFB should intensify its cooperation with DG ECFIN to jointly administer the database on fiscal councils or to draw more heavily on its data.

Member states pushing back against the EFB

The EFB's creation has been described as an ‘experiment at the supranational level’ (Asatryan and Heinemann, Reference Asatryan, Heinemann, Beetsma and Debrun2018). Its experimental character derives in part from its multi-faceted mandate that makes the EFB's work relevant for a wide range of stakeholders (such as finance ministries, national fiscal councils and their umbrella network, court of auditors, the Commission, the IMF, the OECD, and the Eurogroup). First, the EFB is tasked with advising the Commission on the appropriate prospective euro area fiscal stance. This forward-looking part of the mandate is aimed at improving the composition of the individual national fiscal stances within the European Semester. However, the euro area fiscal stance currently amounts to little more than an aggregation of the various national fiscal stances and is fraught with measurement uncertainties (Bańkowski and Ferdinandusse, Reference Bańkowski and Ferdinandusse2017; Kamps et al., Reference Kamps, Cimadomo, Hauptmeier and Leiner-Killinger2017). Appropriate euro area fiscal policy coordination ultimately requires the differentiation of the national fiscal stances, which brings the EFB's recommendations in direct conflict with sovereignty considerations of euro area member states.

Germany and the Netherlands oppose the concept of the euro area fiscal stance because they fear that it is being used as a ‘top-down fiscal coordination tool’ (Freitag and Stosberg, Reference Freitag and Stosberg2018). Those member states that have sufficient space to stimulate the economy to achieve an appropriate growth-friendly euro area fiscal stance might not be willing to use it because it would violate the SGP requirements or because it could lead to an overheating of their economy (Ademmer et al., Reference Ademmer, Boeing-Reicher, Boysen-Hogrefe, Gern and Stolzenburg2016). They also reject that a fiscal stimulus would create significant fiscal spill-over effects in the euro area. Buti (Reference Buti2020: 8) has pointed out that ‘achieving a euro area fiscal stance only via horizontal coordination of national policies is exceedingly difficult. In particular, it has not proven politically viable to aim at an adequate fiscal stance for the euro area as a whole solely via bottom-up coordination. When a broadly acceptable overall stance was achieved, that took place via the wrong distribution between countries in violation of their respective fiscal space’. This shows that the supranational coordination of national capacities is very difficult to achieve in practice even if it originates from a semi-autonomous expert body like the EFB. Member states are not naïve about the Commission's indirect ways of governing their fiscal policy choices and are very reluctant to cede any further budgetary sovereignty to Brussels.

The previous section has described the reasons for the uneasy relationship between the EFB and the national fiscal councils. The lack of the EFB's independence from the Commission has made national fiscal councils sceptical about the benefits of deepened coordination. First, national fiscal councils as the ‘new kids on the block’ (Jankovics, Reference Jankovics, Piroska and Rosta2020) have been focused on establishing their independence and on enhancing their legitimacy. They have been keen to reassert their independence because they did not want to be perceived as technocratic trojan horses by their national publics. This perception would have been highly detrimental to their goal to foster national ownership of the fiscal rules. Second, the EFB's close institutional ties with the Commission make it difficult for national fiscal councils to influence the EFB's decision-making process or to exert decisive influence on the nomination process of new board members. Thus, a completely independent EFB is a necessary but not sufficient condition to intensify the relationship with national fiscal councils. Only if the EFB was to follow a network approach that builds on the capacities of national fiscal councils and gives them a say in the decision-making would national fiscal councils be willing to deepen their ties. However, given that the national fiscal councils have already created their own network of national fiscal councils (EUIFIs), it is unlikely that these parallel structures will be unified.

In some member states, national fiscal councils have developed into reputable fiscal watchdogs that do not shy away from criticizing their national governments in case of non-compliance with the national fiscal rules (Horvath, Reference Horvath2018). Yet, conflict with their respective government can put national fiscal watchdogs in a vulnerable position. Although the institutional set-up can provide some protection from political interference (von Trapp and Nicol, Reference von Trapp, Nicol, Beetsma and Debrun2018), a government that is eager to weaken or dismantle its fiscal council will ultimately succeed. The Hungarian example is instructive in this regard (Kopits and Romhanyi, Reference Kopits, Romhanyi and Kopits2013; Jankovics, Reference Jankovics, Piroska and Rosta2020). If threatened with budget cuts or limited access to information, national fiscal councils might find that seeking protection from the European level offers a welcome re-insurance against a loss of independence.

Nevertheless, the prospects for the creation of a European system of fiscal councils remain slim. Moreover, the OECD's network of parliamentary budget offices and independent fiscal institutions has carried out surveillance missions in the euro area aimed at reviewing national fiscal councils' experience in line with best practice (see e.g. OECD, Reference Von Trapp, Nicol, Fontaine, Lago-Penas and Suyker2017). If the EFB and the national fiscal councils could agree upon legally-enshrined common minimum standards for independent fiscal councils in the euro area, a viable business model for the EFB would be to carry out such surveillance missions against the agreed minimum standards as a form of ‘independent quality control’ (Mijs, Reference Mijs2016; Schwieter and Schout, Reference Schwieter and Schout2018: 39). However, this reform proposal would again presume that the EFB becomes more independent and less reliant on the Commission services for its budgetary and human resources. Claeys et al. (Reference Claeys, Darvas and Leandro2016) have proposed to create a ‘European Fiscal Council’ with far-reaching discretionary powers and accountable to the European parliament. Such a body would be made up of an executive board and the presidents of the national fiscal councils in the EU. Alternatively, the Brussels-based network of independent fiscal institutions in the EU (EUIFIs) could build on their existing work and further refine their minimum standards. If they would take over this role, it would give more power to national fiscal councils.

The rationale for the creation of a ‘watchdog for another watchdog’ (Asatryan et al., Reference Asatryan, Debrun, Heinemann, Horvath, Ódor and Yeter2017) was to increase the compliance rate of member states with the SGP's fiscal rules. This would indirectly help the Commission to re-establish its credibility as an enforcer of the EU fiscal rules. However, if the EFB pursued its role with the necessary rigour, it would inevitably bring it into conflict with the Commission. In 2018, the EFB criticized the Commission for its discretionary interpretation of the rules and for the ineffectiveness of its recommendations to member states (Valero, Reference Valero2018). The criticism might appear in contradiction to the claim that the EFB lacks independence; however, it was likely strategically motivated to dispel any distrust stemming from national fiscal councils that it was too close to the Commission. Most nascent fiscal councils rely on criticizing their political principals to establish their credibility during their early years (Horvath, Reference Horvath2018: 512). Since 2018, the EFB's criticism of the Commission has remained subdued. An alternative explanation might be that the intra-institutional constraints that the EFB is exposed to vary over time enabling it to voice more or less public criticism. For example, the EFB is currently attached to the Commission's Secretariat-General for ‘administrative purposes’,Footnote 11 but in the past the EFB's secretariat had been nested inside the Commission's ‘Deepening EMU’ unit, which might have created a conflict of interest. Given the lack of transparency, one can only speculate how much the EFB criticizes the Commission in its private interactions. Thus far, there is no evidence that this criticism has harmed the EFB even though limited access to information is often hard to detect because a memorandum of understanding can easily be violated. The EFB's criticism can be disregarded because no ‘comply-or-explain’ rule bounds the Commission to issue a formal response to the EFB's annual report. Thus far, the EFB has rarely intervened in real time. It has issued an opinion when it saw the independence of the Danish fiscal council being threatened and supported the Commission's decision to activate the general escape clause during the COVID-19 pandemic. There are signs that the EFB could move towards real-time interventions. Its annual report 2019, for example, contained a factual box that traced the recent evolution of the conflict between the Commission and the Italian authorities over its draft budgetary plan.

Conclusion

This paper has demonstrated that the Commission tries to counter the trend that member states delegate more competences to competing institutions. In the case of the EFB, the Commission created their own supranational de novo body by enlisting independent experts. This type of supranational de novo body lacks financial and operational independence. Member states have limited means of influencing a supranational de novo body's mandate. In principle, the institutional design of the EFB enables it to act as an orchestrator of national fiscal councils. However, the experience of the EFB shows that relying on national fiscal councils as intermediaries is difficult to implement. The national fiscal councils' task to foster local ownership of the fiscal rules would become more difficult if they were perceived as ‘steered by Brussels’. In addition, national fiscal councils have no means to influence the decision-making process within the EFB as long as it remains closely tied to the Commission. Even though the EFB has been critical of the Commission in its 2018 annual report, one cannot draw any inferences about the EFB's degree of independence from this. In the 5 years that have passed since the publication of the five presidents' report, the EFB has been broadly aligned with the Commission's deepening EMU agenda and turned into a prominent advocate for a euro area fiscal capacity. Four potential scenarios for the EFB's future can be envisioned: (i) fully-fledged stand-alone de novo body; (ii) orchestrator with centralized coordination of national fiscal councils; (iii) institutional stasis; or (iv) dissolution of the EFB by the Commission. At the current juncture, one can only speculate which path the EFB will take in the future.

Funding

This research received no grant from any public, commercial, or non-profit funding agency.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Diane Fromage (Sciences Po Paris) for her very helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper. I would also like to thank the participants of the General Virtual ECPR Conference on 27th August 2020 for their insightful feedback. I would also like to express my gratitude to the editor and the two anonymous reviewers for their feedback. The information and views set out in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of any institution that the author is affiliated with or has been affiliated with in the past.