Introduction

The coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic that spread from the city of Wuhan, China in 2020 upset peoples' lifestyle. In most countries, the lockdown imposed by national governments to contain the spread of the virus forced people to stay at home for a prolonged period. In the long run, this situation resulted in dissatisfaction with the measures that had been adopted.

In conjunction with the disruption brought on by the virus, conspiracy theories proliferated on many aspects of the pandemic (Lovari, Reference Lovari2020). In September 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 to be an infodemic, namely, ‘an overabundance of information, including false or misleading information in digital and physical environments during a disease outbreak’ (WHO, 2020).

In the literature on political attitudes, the association between belief in conspiracy theories and populist attitudes is gaining relevance (Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Vegetti and Littvay2017; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Rovira Kaltwasser and Andreadis2020; Erisen et al., Reference Erisen, Guidi, Martini, Toprakkiran, Isernia and Littvay2021). Based on the premise that populist parties (PPs) must resonate with sentiments which are already present in the population (Zaller, Reference Zaller1992), the next step is to investigate whether ‘subjective conspiracist predispositions are exploited by populist leaders to mobilize latent anti-establishment biases and boost their own support’ (Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Vassallo and Vezzoni2017: 329). Therefore, under what conditions do individuals' beliefs in conspiracy theories affect their intention to vote for a PP?

While most studies have focused on explaining the propensity in believing in conspiracy theories (see Uscinki et al., Reference Uscinki, Klofstad and Atkinson2016), ‘little research has focused on assessing whether conspirational attitudes are able to predict certain political behaviors’ (Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Ladini and Vassallo2021: 70). Furthermore, the few studies that have addressed this issue have provided mixed evidence, or they have not directly addressed the association between belief in conspiracy theories and an intention to vote for a PP (Cantarella et al., Reference Cantarella, Fraccaroli and Volpe2019; Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Ladini and Vassallo2021). All in all, the association between belief in conspiracy theories and intention to vote for a PP is still an understudied topic; therefore, the main contribution of this paper will consist in shedding light on the relationship between these two variables during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Amidst COVID-19, PPs had to cope with the management of the emergency. However, depending on their position in the Italian party system (within the government or in the opposition), the strategies adopted to address the pandemic crisis differed substantially (Katsambekis and Stavrakakis, Reference Katsampekis and Stavrakakis2020; Bobba and Hubè, Reference Bobba and Hubé2021). While PPs in the opposition spread fake news for their electoral purposes (Katsambekis and Stavrakakis, Reference Katsampekis and Stavrakakis2020), PPs within the government stressed the necessity of lockdown measures (Bertero and Seddone, Reference Bertero, Seddone, Bobba and Hubé2021).

This paper investigates the impact of belief in conspiracy theories on an intention to vote for PPs in the Italian context. The Italian case study is appropriate for the purposes of this study due to several reasons. First, Italy was ‘hit by the health emergency earlier than any other Western country, thus in a time with greater uncertainty about the virus’ (Vezzoni et al., Reference Vezzoni, Dotti Sani, Chiesi, Ladini, Biolciati, Guglielmi, Maggini, Maraffi, Molteni, Pedrazzani and Segatti2021: 3). Second, the country experienced a worryingly high circulation of conspiracy theories across digital media (Lovari, Reference Lovari2020). Finally, Italy is one of the few countries where relevant PPs are both in power, and in the oppositionFootnote 1. Therefore, it would be extremely interesting to distinguish between PPs in power and in the opposition as well as to test to what extent these differences have played a role in the relationship between belief in conspiracy theories and voting preference.

For the purposes of this study, a cross-sectional analysis has been conducted with the thirdFootnote 2 wave of the original three-wave panel data carried out in December 2020. The results of a multinomial model show that individuals who have uncertainty or unwillingness to receive vaccinations and who are also more likely to believe in conspiracy theories related to the COVID-19 situation are more likely to vote for PPs. Furthermore, the results from two different logistic regression models show that belief in conspiracy theories and distrust in the reliability of the vaccines are associated with a preference for PPs in the opposition; whereas the likelihood to get a vaccination is associated with a higher likelihood to vote for PPs in power. However, the impact of conspiracy theories and anti-vaccine attitudes on intention to vote for PPs in power is less accentuated when compared with the likelihood of voting for the two PPs in the opposition. In this sense, the role played by the Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S) during the vaccination campaign may have contributed to mitigate the impact of these variables on the intention to vote for PPs (Valeriani et al., Reference Valeriani, Iannelli, Pavan and Serani2021; see also Goldstein and Wiedemann, Reference Goldstein and Wiedemann2021).

Theoretical arguments

Defining populism

In this paper, reference is made to scholars who study populism from an ideational approach and consider populism as a coherent set of ideas that can be either used instrumentally or result from a sincere conviction. This branch of the literature has identified three core characteristics of populism: people centrism (the ‘people’ is the paramount subject of populists' political project), anti-elitism (the elite are the enemy of the people), and a Manichaean vision of politics. By reducing the complexity of political and social phenomena to antagonism between an in-group and an elite out-group, the latter implies that the logic is based on a good vs. evil understanding of politics (Mény and Surel, Reference Mény and Surel2002). In this sense, populism can be defined as ‘a thin-centred ideology that considers society to be separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ vs. ‘the corrupt elite,’ and which argues that politics should be an expression of the general will of the people’ (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007: 543).

Populism tries to answer basic questions, namely, ‘what went wrong; who is to blame; and what is to be done to reverse the situation?’ (Betz and Johnson, Reference Betz and Johnson2004: 323). In line with the preceding arguments, the answers to these questions are ‘the government and democracy, which should reflect the will of the whole constituency, have been distorted by corrupt elites; the traditional political elites are to blame for the current undesirable situation in which citizens find themselves; the people must be given back their voice and power through a deep change in the political system’ (Albertazzi and McDonnell, Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2008: 5). These messages are highly appealing in society (Hameleers et al., Reference Hameleers, Bos and de Vreese2017), and their persuasiveness is activated by two mechanisms. First, these messages respond to ordinary people's fears while formulating easy solutions to relevant societal problems and providing clear answers to complex questions (Betz and Johnson, Reference Betz and Johnson2004). Second, by directly referring to all voters and proclaiming to speak on their behalf, PPs transmit a sense of closeness to citizens' needs, in addition to the assurance that once in power, they will solve their problems (Mény and Surel, Reference Mény and Surel2002).

Conspiracy theories and intention to vote for PPs

Conspiracy theories may be defined as ‘explanations of social facts by means of secret arrangement[s] between a small group of actors to usurp political or economic power, violate established rights, hide vital secrets or illicitly cause widespread harm’ (Uscinki et al., Reference Uscinki, Klofstad and Atkinson2016: 58).

By questioning basic processes of democratic accountability, conspiracy mentality leads to a biased perception of some of the most relevant political facts (Martini et al., Reference Martini, Guidi, Olmastroni, Basile, Borri and Isernia2021). Furthermore, like populism, conspiracy theories attempt to reduce the complexity of reality to simplistic arguments. In a similar manner, a conspiracy theory relies on an unresolved conflict between the ‘corrupt elite’ and the ‘pure people’. As Mancosu et al. (Reference Mancosu, Ladini and Vassallo2021: 72) claim, ‘people believing in conspiracy theories are expected to adopt a Manichean perspective where few conspirators are identified with the Evil and millions of individuals with the Good’.

Most of the time, conspiracy theories contradict each other (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Douglas and Sutton2012), but because these theories are not falsifiable (Keeley, Reference Keeley1999), ‘conspiracy believers do not seem to evaluate specific stories in their own merit, but they rather tend to accept the whole package’ (Brothertorn et al., Reference Brothertorn, French and Pickering2013: 1). In the case of conspirational beliefs, the common factor behind the acceptance of individual theories is ‘the idea that authorities are engaged in motivated deception of the public’ (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Douglas and Sutton2012: 768). Under such conditions, conspiracies proliferate in an environment where there is ‘extreme scepticism of the political sphere by a sector of the population that feels excluded, which in turn implies that believing in conspiracies requires the conviction that the only thing politicians can do is being deceptive and plotting secret plans for a global takeover’ (Fenster, Reference Fenster1999: 71). In this sense, belief in conspiracy theories matches the dissatisfied view of politics that is often presented by PPs.

In summary, ‘the worldviews of conspiracy theories and populism are similar. They present simple narratives with two well-defined sides, separated on moral grounds. They view conspirators controlling society, with more resources and willpower, and ordinary people as their victims. Moreover, they both seem to be rooted in general animosity towards anything official’ (Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Vegetti and Littvay2017: 427). Furthermore, populism and conspiracy theories share two characteristics: the tendency to dichotomize discussions (Panizza, Reference Panizza and Panizza2005), and the use of empty signifiers (Laclau, Reference Laclau2005). The combination of these factors eases the activation of latent populist attitudes among the general population, which must resonate within the public to appear and to be influential (Spruyt et al., Reference Spruyt, Keppens and Van Droogenbroeck2016; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Rovira Kaltwasser and Andreadis2020; Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert, Reference Rovira Kaltwasser and Van Hauwaert2020). Under these conditions, people who believe in conspiracy theories are more likely to adopt populist attitudes (Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Vegetti and Littvay2017; Erisen et al., Reference Erisen, Guidi, Martini, Toprakkiran, Isernia and Littvay2021).

Although the work of Castanho Silva et al., has made an important contribution in linking belief in conspiracy theories and populist attitudes, they have focused on the relationship between the two attitudes, which is not the same as analysing the association between a political attitude and the intention to vote for a PP. Therefore, it is worthwhile to highlight that ‘the relationship between conspiracism and vote choice remains obscure’ (Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Ladini and Vassallo2021: 70). In the US, Gunther et al. (Reference Gunther, Beck and Nisbet2019) found that, among those who voted for Obama in the 2012 elections, those who believed in fake news were more likely to vote for Trump in 2016. In Italy, Mancosu et al. (Reference Mancosu, Ladini and Vassallo2021) found a negative and significant association between conspiracy belief and a ‘yes’ vote in the Italian constitutional referendum which took place in 2016. Although the issue was highly politicized (Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Ladini and Vassallo2021), analysing the patterns of voting behaviour in a referendum is not the same as directly analysing an intention to vote for a PP in a national election. By treating voting intention as a predictor for the likelihood of believing conspiracy theories, Mancosu et al. (Reference Mancosu, Vassallo and Vezzoni2017) found that, compared with those who intended to vote for the Partito Democratico (PD), those who were more likely to vote for Forza Italia (FI), Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S), Lega and (to a lesser extent) Fratelli d'Italia (FdI) had a higher likelihood in believing in conspiracy theories. However, Cantarella et al. (Reference Cantarella, Fraccaroli and Volpe2019: 33) claimed that ‘misinformation had a negligible and non-significant effect on the populist vote in Trentino and South Tyrol during the Italian 2018 general elections’. Therefore, more studies are needed in order to understand the association between populist voting and belief in conspiracy theories. In this paper, the following hypothesis will be tested:

H1: Belief in conspiracy theories is positively associated with the intention to vote for a PP.

Anti-vax attitudes and intention to vote for PPs

Among the various conspiracy theories, the one related to vaccines is one of the most widespread and well-documented in the literature (Kata, Reference Kata2012; Lovari, Reference Lovari2020). More specifically, the vaccination issue has been used as an indicator to construct generic conspiracy belief scales (Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Vassallo and Vezzoni2017, Reference Mancosu, Ladini and Vassallo2021). According to Mancosu et al., ‘the conspirational theory applied to vaccination has been promoted by the politicization of the topic, which meshed with the spread of populist anti-elitism movements and the diffusion of conspiracy theories’ (Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Vassallo and Vezzoni2017: 330). Even before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the argument which stated that vaccines are the result of a massive conspiration led by the big pharmaceutical firms for their own economic interests was part of the conspirational thinking (Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Vassallo and Vezzoni2017). In other words, according to the anti-vaccination community, ‘vaccines cause illness; they are ineffective; they are part of a medical/pharmaceutical/government conspiracy; and mainstream medicine is incorrect or corrupt’ (Kata, Reference Kata2012: 3779). Therefore, it follows that:

H2: Anti-vaccine attitudes are positively related to the intention to vote for a PP.

The potentially different impact of conspiracy theories and anti-vax attitudes on an intention to vote for a PP in power or in the opposition

Nevertheless, we should consider the position taken by a PP within the national party system. In fact, depending on their role as a governing or as an opposition party, both the communication strategy and the posture adopted by the party are very different (Albertazzi and McDonnel, Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015; van Spanje, Reference van Spanje2011). When ruling the country (especially in coalition with a mainstream party), a PP must cope with an irresolute contradiction between its new condition as an ‘establishment’ party, and its populist anti-establishment appeal. Under these conditions, a PP loses the purity of its message as the only alternative to mainstream politics, and it ‘can no longer credibly make the claim that it aims to kick the establishment out’ (van Spanje, Reference van Spanje2011: 613). Once in government, PPs also tend to moderate their public discourse in order to appear to be a reliable government partner (Albertazzi and McDonnel, Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015).

Conversely, PPs in the opposition are free from any constraints, which implies that they can adopt a truly populist anti-establishment rhetoric to attack mainstream parties. Moreover, PPs in the opposition radicalize their positions and strengthen their populist messages as a strategy to attract a large number of people who are not happy with the government (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007). These differences were also evident in the context of the COVID −19 crisis (Katsambekis and Stavrakakis, Reference Katsampekis and Stavrakakis2020; Bobba and Hubè, Reference Bobba and Hubé2021). The PPs in the opposition adopted a very aggressive strategy against mainstream and government parties by politicizing the issue, criticizing the lockdown measures and even the conspiracy theories in order to blame the government (Katsambekis and Stavrakakis, Reference Katsampekis and Stavrakakis2020). Conversely, the PPs in government tried to de-politicize the issue and to stress the necessity of the lockdown measures (Bertero and Seddone, Reference Bertero, Seddone, Bobba and Hubé2021).

By gauging the ideological dimension of the government-vs-opposition fracture among PPs in Italy during the Covid-19 pandemic, Valeriani et al. (Reference Valeriani, Iannelli, Pavan and Serani2021) addressed the relevant question as to whether such a distinction in the roles played by the different PPs was reflected in a more critical or an optimistic view about the vaccines. As they showed, right-wing individuals, and those who refrain from identifying with any point on the ideological scale, are significantly more distrustful of anti-covid vaccines when compared with left-wing individuals. But, even more importantly, they also demonstrated that right-wing individuals, (that is, those who are ideologically closer to the two PPs in the opposition), are significantly more distrustful of anti-covid vaccines compared to the unidentified individuals. Keeping in mind that the unidentified are most likely to vote for M5S (Bordignon and Ceccarini, Reference Bordignon and Ceccarini2013), this may be explained by the fact that the role played in the government by the populist party M5S (by leading and carrying out the entire vaccination campaign) contributed to mitigating scepticism towards the vaccines (Valeriani et al., Reference Valeriani, Iannelli, Pavan and Serani2021). This evidence is in line with Goldstein and Wiedemann (Reference Goldstein and Wiedemann2021) who stated that the positioning of political actors in national party systems (either within government or in the opposition) has had a significant impact on people's attitudes towards the COVID-19 pandemic and the related vaccination issue. In this paper, these findings will be taken a step further in order to investigate under what conditions the government-vs-opposition differences between PPs regarding vaccines were reflected in Italians' intention to vote. Therefore, it is proposed that:

H3: The impact of belief in conspiracy theories and anti-vax attitudes is more accentuated in the case of PPs in the opposition.

Context of the study

In Italy, the COVID-19 crisis crushed the second Cabinet formed under the leadership of Giuseppe Conte (Conte II), which comprised an alliance between M5S, the centre-left PD, Italia Viva – IV (the new party that Renzi formed after the division within the PD), and the left-wing Liberi e Uguali (LeU). Three weeks after the detection of the first case of COVID-19 in Italy, the government declared a national lockdown, making Italy the first western democracy to adopt such a decision. ‘Phase 1’ of Italy's pandemic management, which corresponded to the national lockdown that lasted from 9 March to 31 May 2020, created the perfect breeding ground for the proliferation of conspiracy theories among the general population (Lovari, Reference Lovari2020). AGCOM (2020) found that as a proportion of disinformation published online, coronavirus content increased from 5% in early January 2020 to 46% in late March 2020. Regarding social media, coronavirus posts increased to 36% of all messages produced by disinformation sources. Part of this disinformation was linked to conspiracy theories (EEAS 2020).

Unlike other countries – where PPs spread misinformation to attack mainstream parties (Bobba and Hubè, Reference Bobba and Hubé2021) – in Italy the situation developed in a different way since PPs were in both the government and the opposition. In fact, FdI, Lega, and M5S adopted a different strategy regarding the management of the pandemic crisis. In the opposition, Lega and FdI polarized the management of the pandemic and claimed that the lockdown should be abolished as soon as possible (Bertero and Seddone, Reference Bertero, Seddone, Bobba and Hubé2021). On the other hand, ‘the M5S, as a government party, emphasized its responsiveness by appealing for national unity and claiming the ownership for those governmental actions providing direct support to citizens’ (Bertero and Seddone, Reference Bertero, Seddone, Bobba and Hubé2021: 46).

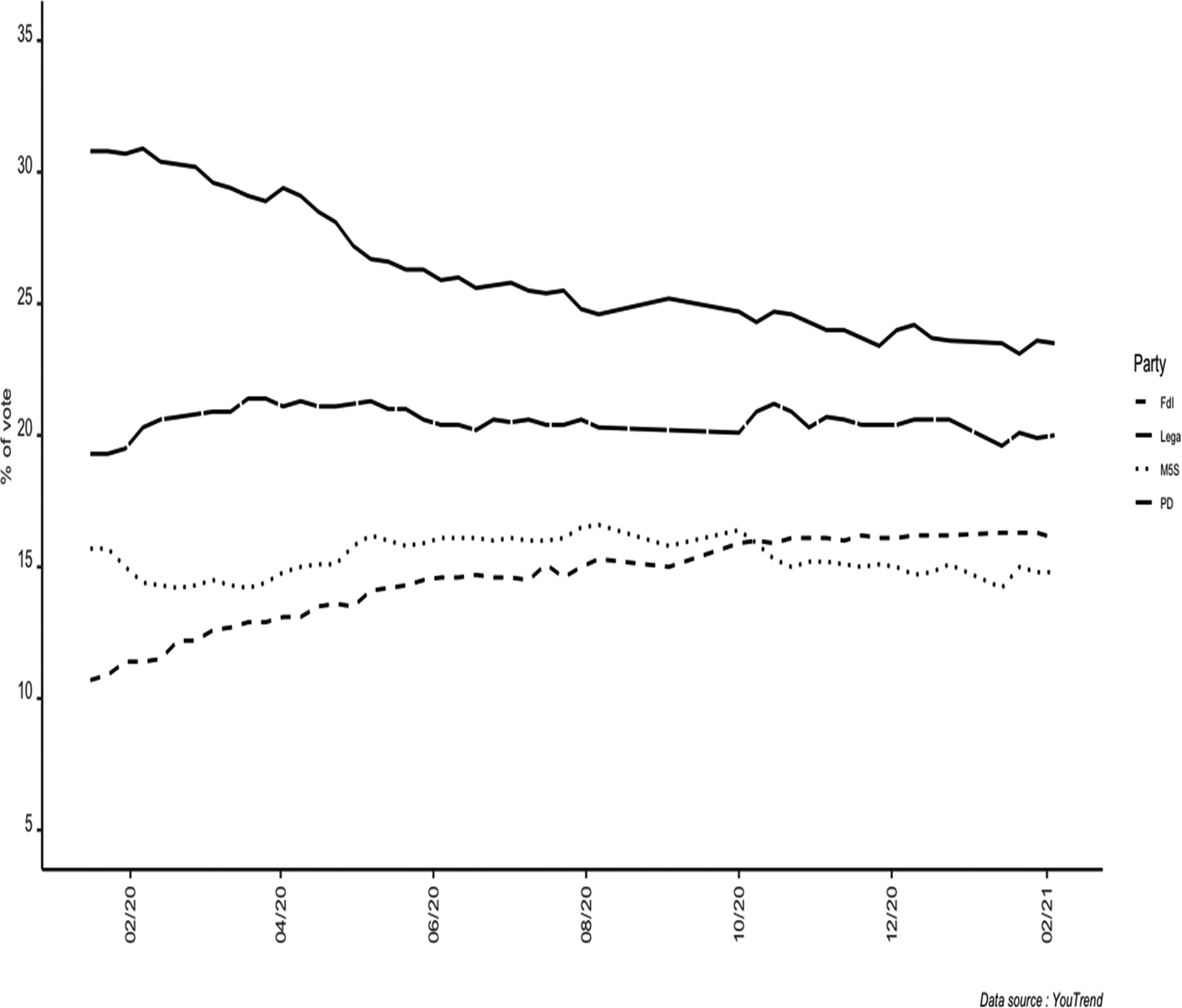

After the conclusion of the national lockdown, many of the restrictions on citizens' freedom were gradually lifted, and Italy entered ‘Phase 2’ of pandemic management during which political tensions over restrictions were exacerbated. From September 2020, Italy experienced another increase in the number of deaths, bringing the country into ‘Phase 3’ (from 26 October 2020 to March 2021), in which ‘lighter’ and ‘harder’ lockdowns were alternated. According to the government, the stricter measures were adopted to avoid another hard lockdown. Nevertheless, the new restrictive measures were not approved by the population. According to a survey administrated by SWG on 26 October 2020, 25% of the interviewees declared that the new measures were excessive, and 61% disapproved of the ‘light’ lockdown (SWG 2020). As Figure 1 shows, (which reports the average intention to vote as collected by the main Italian polling agencies and aggregated by YouTrend 2021), the management of the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy had a different impact on the evolution of the intention to vote for the main political parties.

Figure 1. Intention to vote for the main Italian parties (01/20–02/21).

The Lega (the solid line on the top of the graph) was strongly affected by the COVID-19 crisis. The party lost 8 percentage points in terms of intention to vote. FdI was the party that benefitted the most from the decline of its counterpart. As can be observed in Figure 1, the party showed an increase from 10% in intention to vote on January 2020 to 16% 1 year later. Conversely, the two main government parties (PD and M5S) maintained quite a stable level of intention to vote. Under these conditions, the coalition faced a second government crisis in less than 2 years, which resulted in the resignation of Giuseppe Conte in January 2021 and the consequent government reshuffle 1 month later. The process culminated with the designation of Mario Draghi as the new Prime Minister of a coalition which left the FdI as the only PP in opposition.

Data and methods

Data

To test the hypotheses formulated in the previous section, the third wave of an original three-wave CAWI survey was applied to a sample that is representative of the adult Italian population with internet access. The survey was administrated by a commercial research institute (Swg Spa) and the sample was derived from an opt-in online community from the same research institute, with quotas for gender, age, education, working condition and area of residence.

Survey participants were rewarded with non-monetary incentives to join the study. Wave 1 was fielded from 18 to 28 May 2020; Wave 2 was administrated between 31 August and 13 September 2020; the third wave of the panel study was fielded from 2 to 20 December 2020. After the conclusion of the longitudinal study, a strict data-cleaning protocol was implemented to improve the quality of the datasetFootnote 3. As a result of this process, the final sample was as follows: 1563 valid interviews in Wave 1, 1353 in Wave 2; 1299 in Wave 3; 1204 panellists completed the entire study. In the definitive dataset, the completion rate in Wave 1 was 34%, the retention rate between Wave 1 and 2 was 86.6%, with 77% for the entire study. Thus, the data suffered from attrition, and as this is not a random phenomenon it may possibly bias the empirical results (Frankel and Hillygus, Reference Frankel and Hillygus2014). Following the strategy of Vezzoni et al. (Reference Vezzoni, Dotti Sani, Chiesi, Ladini, Biolciati, Guglielmi, Maggini, Maraffi, Molteni, Pedrazzani and Segatti2021), the effects of attrition have been partially accounted for by weighting the data by socio-demographic characteristics when computing the summary statistics (see Appendix C), while the models control for gender, age, education, working condition and area of residence.

Measuring intention to vote for populist and mainstream parties

The dependent variable is the self-reported intention to vote if a national election were held tomorrow. This categorical variable contains the main political parties (PD, FI, Lega, FdI, IV, M5S and LeU), plus a residual category formed by all the other small parties. Undecided, blank/null votes, those who preferred to not respond, and abstainers have been excluded from the analysis.Footnote 4

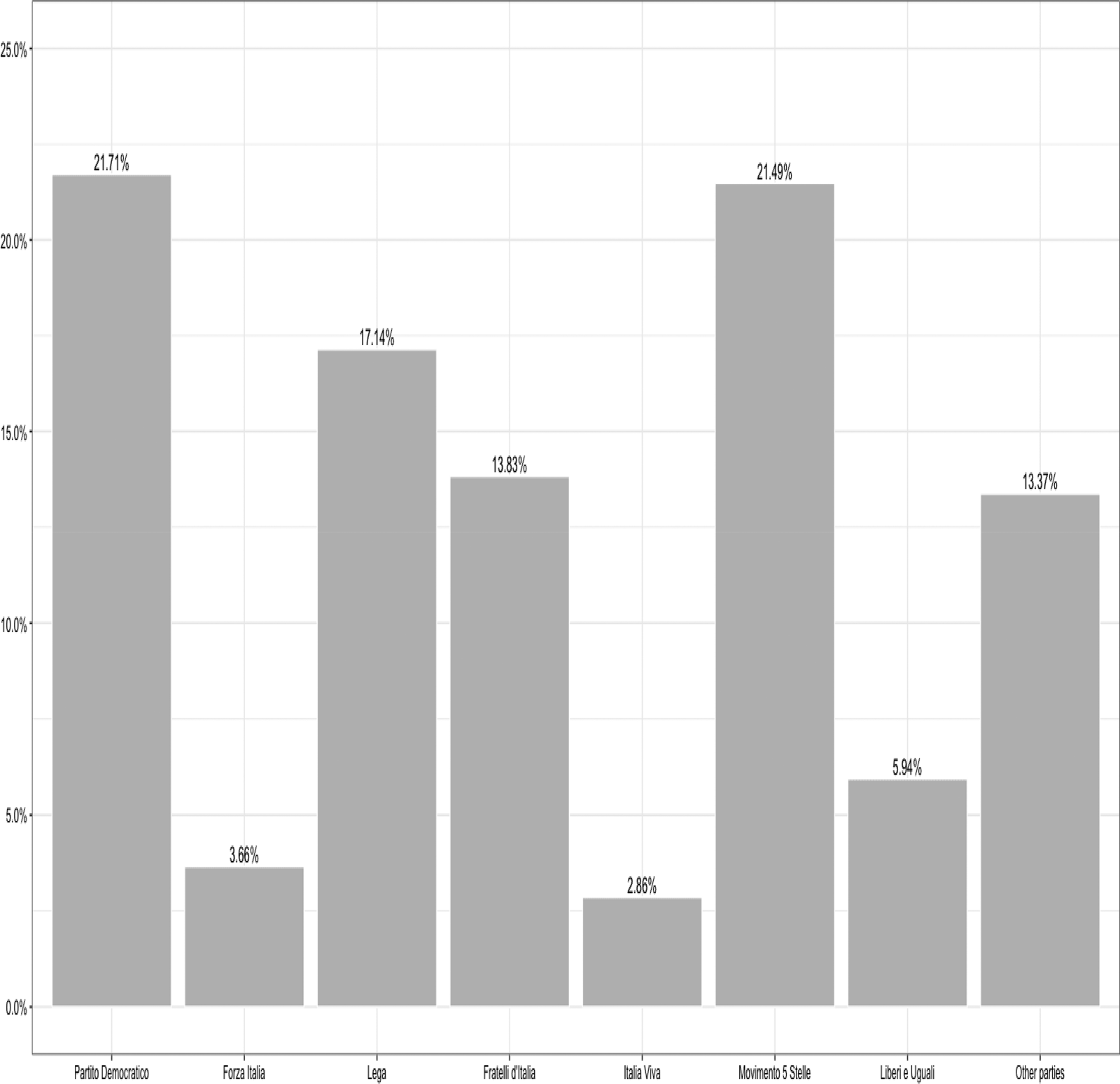

Figure 2 shows that the distribution of the dependent variable is sufficiently spread. Despite the crisis of consensus during Phase 3 of the pandemic management, PD and M5S remained as the most attractive parties, and the main opposition party by that time (Lega) took third place. In fourth place was FdI.

Figure 2. Percentage distribution of intention to vote.

In this study, the approach that Serani (Reference Serani2020) used to distinguish between mainstream and PPs was followed: the anti-elite and people-vs-elite dimensions in the 2019 Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2020) were used. The survey was administered in winter 2020 and it asked 421 political scientists to rate 277 parties on the most relevant issues (e.g. political ideology). However, more importantly, for the first time, the dataset provides information on the positioning of political parties on two different but interconnected variables, which gauge the core populist characteristics: the anti-elite salience and the people-vs-elite dimensions. Both variables are measured on a zero to ten-point scale. The inclusion of these variables in the expert survey is particularly relevant because, according to a review of the literature, ‘there are no existing party-level measures of anti-establishment rhetoric salience’ (Polk et al., Reference Polk, Rovny, Bakker, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Koedam, Kostelka, Marks, Schumacher, Steenbergen, Vachudova and Zilovic2017: 3). For the purposes of this research, the parties above the mean value of both variables have been classified as a PP. Conversely, all the parties below the threshold are considered ‘mainstream parties’. As illustrated in Figure 3, FdI, M5S and Lega are in the ‘populist party’ categoryFootnote 5. Having said that, we should recall that the parties are different regarding their role in the Italian party system. While FdI and Lega were in the opposition, the M5S was the main coalition partner of the mainstream PD. As Albertazzi and McDonnell (Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2015) stated, this aspect may matter when explaining the impact of the covariates on the intention to vote. Therefore, two different dummy values have also been computed: populist opposition parties (coded as 1) vs. mainstream parties (coded as 0); PP in power (1) vs. mainstream parties (0).

Figure 3. Placement of the main Italian on the anti-elite and the people vs. elite dimensions.

Measuring belief in conspiracy theories and anti-vax attitudes

The hypotheses formulated in the theoretical section will be tested by using three different variables and indicators. The first is an index measuring the levels of respondents' knowledge about the COVID-19 pandemic. Panellists were asked to respond to eight true or false statements and were also offered the option: ‘I don't know’. Five statements were related to medical aspects of the pandemic which had been created from notes published on the official website of the Italian Health MinistryFootnote 6 in a section aimed at debunking fake news that had been circulating during the first months of the COVID-19 emergency. One statement (only in the second and third wave of the study) dealt with the rumour concerning the possibility that immigrants had contributed to the diffusion of the virus the last fall (Pagella Politica, 2020), while the remaining two statements were related to the relationship between Italy and the European Union, or with other countries, in the management of the pandemic (EEAS 2021). While correct evaluations (true when the news was true and false when the news was false) were coded as 1, the incorrect and ‘I don't know’ responses were coded as 0. Among these items, the ones which better gauge the conspiracy dimension related with the COVID-19 pandemic were selected, as follows:

The Coronavirus that generated the COVID-19 pandemic was created in a Chinese laboratory. (False, correctly evaluated by 47.8% of respondents.)

The spread of the COVID-19 pandemic was facilitated by the installation of 5 G antennas. (False, correctly evaluated by 86% of respondents.)

• Immigrants landing in Italy are mainly responsible for the increase in the number of COVID-19 infections. (False, correctly evaluated by 74% of respondents.)

The resulting dummy values are summed in a 0–3 index (Crombach's α: 0.7) in which the lower the index, the higher the individuals' propensity to believe in conspiracy theories. Conversely, the higher values of the scale entail a more informed knowledge of the COVID-19 pandemic or, at least, adhesion to the ‘official truth’ shared by official authorities.

To test the second hypothesis, two covariates were used that are related to the panellists' attitudes towards the vaccination campaign that began during the end of December 2020. In the dataset, two variables measure these attitudes. The first is the propensity to get the vaccination against COVID-19 once it is available. The question is measured on a 3-point scale in which 0 represents the intention to not get the vaccination, and 3 represents the clear intention to get the vaccination. The other variable is related to confidence about the reliability of the vaccines, which is measured on a 3-point scale, where 0 indicates that ‘the vaccines will not be reliable at all’, and 3 indicates that ‘they will be reliable for sure’. Although both indicators gauge an individual's anti-vaccine attitude, the two variables are slightly different. While trust in the reliability of the vaccines gauge an individual's trust in science and in the government's vaccination campaign to some extent (Valeriani et al., Reference Valeriani, Iannelli, Pavan and Serani2021), an individual's likelihood of actually getting vaccinated may be associated to more personal or specific reasons. With that in mind, both the decision of not getting vaccinated and people's distrust in the reliability of the anti-covid vaccines involve an adhesion to (or the acceptance of) anti-scientific or conspiracy theories regarding the vaccination issue.

In search of potential confounding factors

Added to the model are also those variables that may have an impact on both the dependent variable and the main covariates of interest. The first variable is the self-reported placement on the left–right scale. Ideology is one of the strongest predictors of voting behaviour in Italy (see Biorcio Reference Biorcio, Bellucci and Segatti2010), but it is also associated with the propensity to believe in conspiracy theories (Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Vassallo and Vezzoni2017, Reference Mancosu, Ladini and Vassallo2021) or to adopt a sceptical attitude towards the vaccines (Valeriani et al., Reference Valeriani, Iannelli, Pavan and Serani2021), justifying the necessity to include such a variable in the empirical model. Given the high number of people who did not identify with any point on the scale (22% of the total), the variable was recoded into a categorical variable: far-left (0–1), centre-left (2–3), centre (4–6), centre-right (7–8), far-right (9–10) and unidentified. In the model, centrists were treated as the reference category.

Likewise, there is also a need to consider political trust since it is strongly associated with both populist preferences (Alvarez et al., Reference Alvarez, Kiewiet and Núñez2018) and belief in conspiration theories (Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Vegetti and Littvay2017; Vezzoni et al., Reference Vezzoni, Dotti Sani, Chiesi, Ladini, Biolciati, Guglielmi, Maggini, Maraffi, Molteni, Pedrazzani and Segatti2021). As for ideology, it is necessary to test whether any impact on the association between intention to vote for a PP and belief in conspiracy theories remains once political trust is taken into consideration. For this purpose, trust in the national parliament has been included in the model, which is measured on a 3-point scale, where 0 means ‘no trust at all’ and 3 means ‘complete trust’.

Further, it is relevant to consider the impact of an individual's media diet and attitudes towards the traditional sources of information regarding the belief in conspiracy theories and an intention to vote for PPs. In this regard, it has been shown that information from social media is related to both a belief in conspiracy theories (Kata, Reference Kata2012; Lovari, Reference Lovari2020) and an affinity for PPs (Gerbaudo, Reference Gerbaudo2018). In a similar way, people who get informed through traditional media sources, (namely radio and TV), are more likely to adopt a positive attitude towards the vaccines (Valeriani et al., Reference Valeriani, Iannelli, Pavan and Serani2021). Likewise, the attitude that favours anti-mainstream news media indicates a likelihood to vote for PPs (Gerbaudo, Reference Gerbaudo2018). Therefore, the frequency of information from social media and trust in the main national newspapers have been included in the model. The former is measured on a 4-point scale, in which 0 indicates that s/he never uses social media to get informed, and 4 indicates that s/he gets informed from social media several times per day. Trust in the main national newspapers is measured on a 4-point scale, where higher values entail higher confidence in the news that is reported by mainstream media outlets.

In a similar way, it is also necessary to take into consideration the impact of the economy on voting behaviour. In this sense, a distinction has been made between sociotropic and egotropic evaluations of the economy (Duch and Stevenson, Reference Duch and Stevenson2008). Although the former is operationalized by satisfaction with the government's management of the economic situation in the last 2 months, the latter has been measured by using the economic uncertainty index. The index (Crombach's α: 0.85) is on a 3-point scale and is created by using three items measuring respondents' concerns with paying bills, reducing their life-quality level and paying the rent. Finally, the statistical model includes controls for the main sociodemographic variables, namely, gender, age, working status, area of residence and educational level.

Testing the association between belief in conspiracy theories, anti-vax attitudes and intention to vote for PPs

The dependent variable and the covariates have been measured simultaneously. Further details on the operationalization of the variables are presented in Appendix B. Given the nature of the dependent variable and the characteristics of the dataset, a cross-sectional multinomial model has been estimated (using as reference category voting for the PD, the main mainstream party). To test the validity of the third hypothesis more correctly, two different logistic regression models have also been estimated, which replicate the multinomial model, but they distinguish between voting for a PP in opposition (first model) and in opposition (second model), vs. the intention to vote for mainstream parties.

Results

Table 1Footnote 7 contains the parameters of the multinomial model. Notably, it is important to check the self-reported placement on the left–right scale. All the signs of the coefficients displayed in Table 1 are in line with the original expectations. Although those intending to vote for FI, Lega and FdI tend to have a right-wing ideology, those who are more likely to vote for the left-wing Liberi e Uguali locate themselves at the extreme-left side of the ideological spectrum. As expected by the ambiguous posture adopted by M5S in its relationship with the traditional left–right cleavage (Bordignon and Ceccarini, Reference Bordignon and Ceccarini2013), the unidentified have a much higher likelihood to vote for this party. Also, mistrust in traditional media sources seems to play a role when explaining an intention to vote for PPs. More precisely, the more accentuated mistrust is in the main national newspapers, the higher the likelihood of voting for Lega and M5S. However, this variable does not play any role in explaining a vote for FdI.

Table 1. Multinomial models predicting the intention to vote for the main Italian parties (ref. PD)

* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

Regarding the impact of sociotropic evaluations of the economy on the intention to vote, Table 1 shows that negative evaluations of the government's management of the economy are associated with a higher likelihood to vote for Lega and FdI. Conversely, a positive evaluation of the management of the economy is related to a higher propensity to vote for M5S. The latter finding may be explained by the fact that by that time M5S was the coalition party with PD, the former premier (Conte) was very close to M5S. This finding shows the necessity of distinguishing between PPs in power and in opposition. On the other hand, trust in the national parliament and the frequency of information from social media do not play any role when explaining an intention to vote for such parties.

Next, the paper focuses on a discussion of the key covariates of the previously stated theoretical argument. First, the index of knowledge regarding COVID-19 is discussed. Table 1 shows that, concerning ideology, political trust and media consumption, the less valid knowledge there is about the COVID-19, (and therefore, the more individuals consider conspiracy theories to be ‘true’ news), the higher the intention is to vote for the two PPs in the opposition (and, to a much lower extent, for the FI party, although the P-value is very close to 0.05), with FdI displaying a stronger impact. Conversely, this variable does not play any role when explaining the likelihood of voting for M5S. These findings are partially in line with Mancosu et al. (Reference Mancosu, Vassallo and Vezzoni2017) analysis, in which they have concluded that those who intend to vote for FI, Lega, FdI and M5S are more likely to believe in conspiracy theories. Therefore, we can partially confirm H1 regarding the association between belief in conspiracy theories and intention to vote for PPs.

With regards to the second hypothesis, Table 1 shows that the variables related to anti-vax attitudes play a significant role in voting intentions. Notably, individuals' propensity to get the vaccination is significantly related to only the intention to vote for M5S. The direction of the relationship is as expected, thus, the lower the likelihood is to get the vaccination, the higher is the likelihood to vote for the populist M5S party. However, trust in the reliability of the vaccines is significantly associated with FdI and Lega. These findings provide sufficiently solid evidence in favour of the second hypothesis.

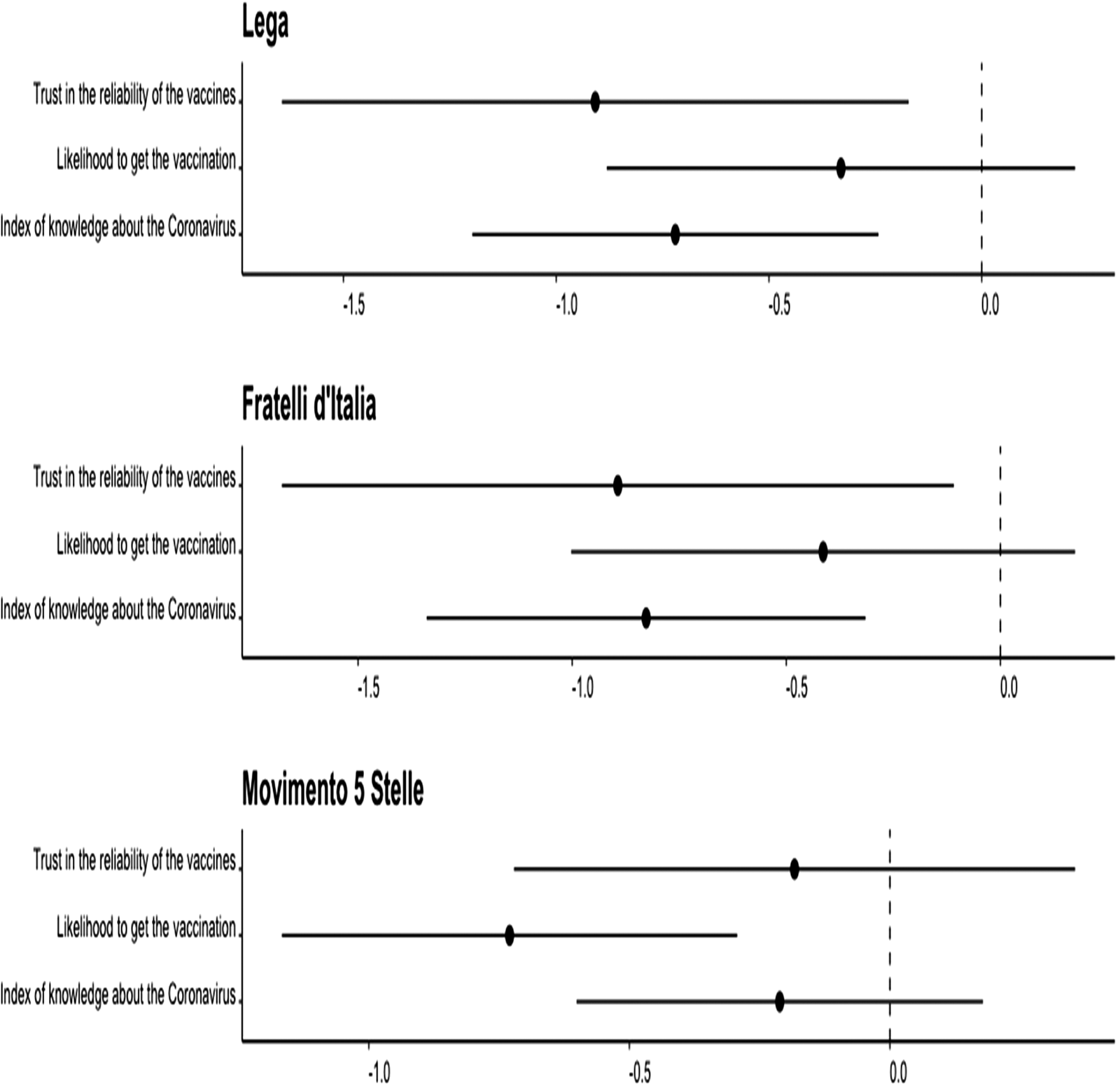

To improve the understanding of the impact of the main covariates of interest on the Italians' voting intention, Figure 4 plots parameter estimates of the multinomial model (solid lines represent 95% confidence intervals). For clarity, only the coefficients of the main covariates for the three PPs are reported.

Figure 4. Coefficient and standard errors plot of the main covariates of interest.

In the following graph, (mis)trust in the reliability of the vaccines and the conspiracy index are the strongest determinants of the voting intention for Lega. Distrust in the reliability of vaccines and the conspiracy index are the factors that better explain the intention to vote for FdI over PD. Finally, the propensity to get the vaccination leads individuals towards M5S.

With this in mind, we should take a closer look at the distinction between PPs in power and in opposition. For this purpose, Table 2 reports the coefficients of two separate logistic regression models (the full models are available in Appendix E). As we can observe, the results are in line with the model displayed in Table 1. A belief in conspiracy theories and distrust in the anti-covid vaccines are associated with a likelihood to vote for PPs in the opposition, while likelihood to get the vaccination is associated with a higher propensity to vote for M5S. However, we can observe that the impact of conspiracy theories and anti-vax attitudes is more accentuated in the case of Lega and FdI, in comparison to those who are likely to vote for M5S. In this sense, the role played by M5S during the vaccination campaign may have contributed to mitigate the impact of these variables on the intention to vote (Valeriani et al., Reference Valeriani, Iannelli, Pavan and Serani2021). Therefore, the third hypothesis can be accepted: the impact of conspiracy theories and anti-vax attitudes is more accentuated in the case of PPs in the opposition.

Table 2. Logistic regression models predicting the intention to vote for the populist government and opposition parties (as opposed to mainstream parties)

* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

Conclusions

This paper provides insights into the association between belief in conspiracy theories, anti-vax attitudes and voting intention during the COVID-19 pandemic, which is an association that has been neglected. For the purposes of this study, three different variables were chosen: an index of knowledge about the Coronavirus, a likelihood to get the vaccination and trust in the reliability of the vaccines. The data employed in the analysis are from the third wave of an original panel survey, fielded in Italy in December 2020.

As discussed in the prior section, these variables have a different impact on the voting intention of the three PPs, depending on their role as opposition (Lega and FdI) or government (M5S) parties. The index of knowledge about COVID-19 is a good predictor for voting for Lega and FdI. This finding is partially in line with Mancosu et al. (Reference Mancosu, Vassallo and Vezzoni2017), which demonstrates how voting intention affects the likelihood to believe in conspiracy theories. Furthermore, distrust in the reliability of the vaccines predicts an intention to vote for right-wing PPs. Finally, a propensity to get vaccinated is significantly associated with an intention to vote for M5S, however, the impact of conspiracy theories and anti-vax attitudes on the intention to vote for the PP in power is less accentuated when compared with an intention to vote for Lega and FdI, the two PPs in opposition. This finding complements Valeriani et al. (Reference Valeriani, Iannelli, Pavan and Serani2021) results. By analysing the opposite relationship, (which factors may explain an individual's trust in anti-covid vaccines), they have demonstrated that right-wing individuals are significantly more distrustful than those who are unidentified. In this sense, the role played by M5S during the vaccination campaign contributed to greatly mitigate M5S supporters' scepticism. However, by analysing the impact of ideology on an individual's trust in the vaccines is not the same as analysing the impact of anti-vax attitudes on the intention to vote. Therefore, this paper also takes the evidence shown by Valeriani et al. (Reference Valeriani, Iannelli, Pavan and Serani2021) a step further.

Considering the above, FdI and Lega voters are much more similar, while those who vote in favour of M5S seem to follow a different pattern. In summary, these findings confirm the validity of the three hypotheses. As Goldstein and Wiedemann (Reference Goldstein and Wiedemann2021) demonstrated in the U.S., and Valeriani et al. (Reference Valeriani, Iannelli, Pavan and Serani2021) in Italy, it is important to take into consideration the different roles played by the three PPs in Italy regarding the vaccination campaign. In particular, the empirical evidence seems to suggest that the impact of (mis)trust in the anti-covid vaccines on the intention to vote can be explained by the different roles played by the three PPs in the Italian party system.

This paper may contribute to the consolidation of the literature on the association between belief in conspiracy theory and intention to vote for PPs during the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, this study attempts to extend the findings on the foundations for and the consequences of belief in conspiracy theories (see Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Vegetti and Littvay2017; Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Vassallo and Vezzoni2017, Reference Mancosu, Ladini and Vassallo2021). This topic is especially relevant in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, which, because of the increasing role played by social media, triggered the spread of conspiracy theories (Lovari, Reference Lovari2020). Additionally, belief in the conspiracy has a significant impact when explaining the electoral attractiveness of PPs, although it is important to consider the role of a particular party in the national party system. Consequently, this paper complements previous studies addressing a similar topic (see Castanho Silva et al., Reference Castanho Silva, Vegetti and Littvay2017; Erisen et al., Reference Erisen, Guidi, Martini, Toprakkiran, Isernia and Littvay2021; Valeriani et al., Reference Valeriani, Iannelli, Pavan and Serani2021).

This study is not exempt from limitations. First, this research represents a case study; thus, the findings are limited to the situation of a specific country. In particular, the fieldwork was conducted during a period of uncertainty about the new anti-covid vaccines, namely, when the vaccines had not yet been released for administration to the public, and the European Medicines Agency had just approved their usage. Therefore, we should take into consideration the timing of the survey when analysing the impact of anti-vax attitudes on the intention to vote for PPs. Second, although the data are from an online panel survey, the empirical analysis relies on only the third wave of the study. Therefore, the cross-sectional nature of the analysis requires a much more cautious approach regarding the direction of the causality of the associations observed in the previous sections. In fact, in the literature, there is sufficiently solid empirical evidence in favour of the impact of the intention to vote (as well as ideology) on an individual's belief in conspiracy theories or trust in the reliability of the vaccines (Mancosu et al., Reference Mancosu, Vassallo and Vezzoni2017; Valeriani et al., Reference Valeriani, Iannelli, Pavan and Serani2021; Vezzoni et al., Reference Vezzoni, Dotti Sani, Chiesi, Ladini, Biolciati, Guglielmi, Maggini, Maraffi, Molteni, Pedrazzani and Segatti2021). In this regard, further research is necessary in order to uncover the relationship between conspiracy theories, anti-vax attitudes and voting behaviour. More specifically, future studies should pay more attention to comparative longitudinal surveys which cover a longer timespan or include more countries. In this way, we can more directly address the causality issues, while at the same time we can extend the temporal and geographic range of the findings by improving the generalizability of the findings.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2021.56.

Funding

The author acknowledges support from the project ‘I-Polhys – Investigating Polarization in Hybrid Media Systems’ funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research within the PRIN 2017 framework (Research Projects of Relevant National Interest for the year 2017); project code: 20175HFEB3

Data

The replication syntax is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp. The replication dataset is currently available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers and Professor Augusto Valeriani for their insightful comments.

Conflict of interest

None.