The 2018 Italian general election, held under a new electoral system, inspired a lively academic debate about the electoral campaign, the electoral outcomes, and the process of government formation. In this article, I offer a review of six volumes published in the aftermath of the election. These are edited books sharing a similar structure, that is a division into thematic chapters dealing with the pre-electoral phase, the electoral campaign, the impact of the new electoral rules, and the variables considered relevant to explain the electoral outcomes. The volumes under review – listed in Table 1 – are based on extremely rich datasets including pre-electoral and post-electoral surveys; content analysis of party manifestos and media; and secondary analyses on electoral and parliamentary data.

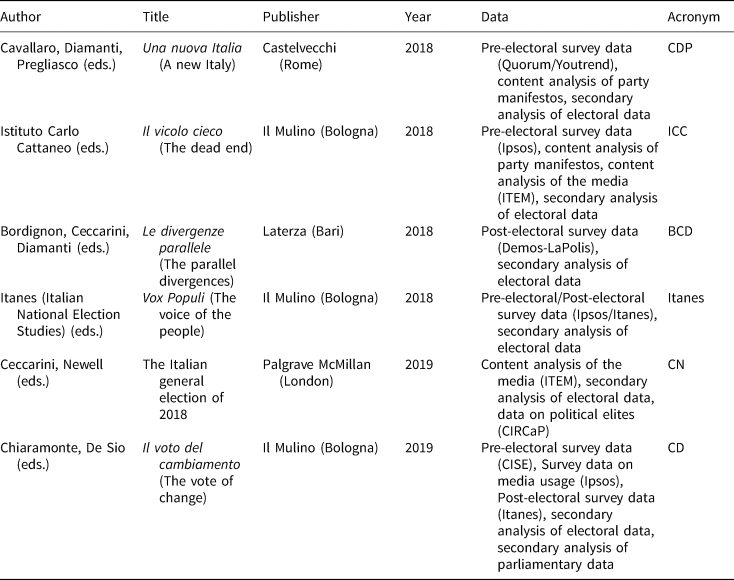

Table 1. List of books on the 2018 Italian general election

Note: The books are reported in chronological order of publication. Author's translation of Italian titles.

This article does not claim to be a complete and detailed review, but it aims at highlighting some of the insights offered by the contributions included in those volumes. To this purpose, I will rely on the conceptual framework on critical elections provided by Key (Reference Key1955). The author (p. 4) defined critical elections as those ‘in which more or less profound readjustments occur in the relations of power within the community, and in which new and durable electoral groupings are formed’. These exceptional contexts should produce sudden and enduring realignments in the partisan loyalties of voters, in the social basis of party support and in the ideological basis of party competition (Evan and Norris, Reference Evans and Norris1999). Critical elections should be capable to move the party system to a new equilibrium, with relevant consequences for party system institutionalization. To what extent can the 2018 Italian general election be considered as critical? I will examine how the contributors of those volumes answer to this question by focusing on three major dimensions of change in comparison with the 2013 election: changes in the patterns of party competition; changing patterns of voting behaviour in terms of socio-economic characteristics of the electorate; and changes in the salience of issue cleavages and in the way new issues affected the electoral outcomes.

New patterns of party competition?

The Italian general election of March 2018 shows important changes in comparison with the 2013 election. Undoubtedly, the most impressive one was the defeat of the two mainstream parties, the Partito democratico (Democratic Party, PD) and Forza Italia (Go Italy, FI), which lost more than five million of votes. Such a defeat was largely compensated by the victory of two challenger parties: the Movimento cinque stelle (Five Star Movement, M5S) and the Lega (League). As the time-series reported by Valbruzzi (ICC) show, for the first time in the republican history challenger parties won more votes than mainstream parties. Compared to 2013, the M5S further expanded its constituency, winning almost one third of the votes – a striking result for a party that had contested its first election only five years earlier and – contrary to empirical regularities observed for new parties – was able to improve its performance after its extraordinary initial success. The League, the oldest party in the Italian party system, that had been part of several governments between 2001 and 2011, increased its vote share by four times. Although for this reason it does not perfectly fit the definition of a challenger party, all the studies under review agree on underlining the discontinuity marked by the new leadership of Matteo Salvini such that the party may be considered as a challenger. However, as discussed in De Sio (CD), some ambiguities remain, as the League contested the election as an ally of the mainstream FI party within a pre-electoral coalition. The League's unprecedented success contributed to the overall performance of the centre-right electoral alliance.

The study of electoral fluxes between 2013 and 2018 – based on both survey data and ecological analyses – casts further light on the aggregated results described above. Even though data about vote shifts were collected at different time points and derived from distinct samples, they all agree that the two most successful parties – the M5S and the League – were capable to retain most of their voters from one election to the next. This result emerges in particular from the contributions of De Sio and Schadee (Itanes), De Sio (CD), and Bordignon (BCD), who use survey data to compute electoral fluxes, but also from the ecological analyses reported by Vignati (ICC).On the other hand, both the M5S and the League managed to channel flows from other parties: the M5S from parties positioning themselves along the entire political spectrum – primarily from the PD, but also from the League and the FI, especially in the South; the League mainly from its allies in the centre-right coalition, but also from vote abstention and the M5S – particularly in the North and in the Red belt. As argued by Chiaramonte and Paparo (CN), these geographical variations help to explain the different performance of the M5S in the South and in the rest of the country. The vote shifts discussed above highlight that only a few voters switched from the centre-left to the centre-right suggesting, as De Sio (CD) and Chiaramonte and Paparo (CN) noted, that dissatisfied voters belonging either to the centre-left or to the centre-right chose the M5S as a kind of exit strategy from the two main ideological blocks.

Overall, the analysis of electoral fluxes indicates that the number of switchers corresponds to about one third of the electorate, a figure that is lower than that registered in 2013. A similar trend is observed by measuring vote switching through the Pedersen volatility index, used by Chiaramonte and Emanuele (CD) and Chiaramonte and Paparo (CN) in their chapters. Although it declined by about ten points compared to 2013, the electoral volatility registered in 2018 is the third highest value in the republican history. However, in comparison with the 2013 election, in the 2018 election the volatility is almost entirely the product of switching among existing parties and it does not depend from party system innovation, that is new parties, such the M5S in 2013, entering for the first time in the competition. The high level of volatility observed once again in 2018 reflects therefore a substantial change in the balance of power between parties and ideological blocks, an indicator the De Sio (CD) uses to study the electoral change in his chapter. The 2006 election represents the exemplar case of the bipolar structure of party competition in the Italian Second Republic as the centre-left and centre-right coalitions collected 99.5% of the votes. In 2018, the defeat of the centre-left and the significant growth of the M5S and the centre-right created the condition for what Valbruzzi (ICC) defined an ‘imperfect tripolarism’. This outcome represents a further change in comparison with 2013, in which the consensus for the M5S and the two main cartels was more balanced.

New patterns of voting behaviour?

Given the major shifts in party loyalties described above, we should expect to see also variations in the social bases of party support in comparison with the 2013 election. Although some inconsistencies emerge across the figures reported by using different survey data, all the analyses presented in the books under review confirm that significant changes occurred in comparison with the past. As all the contributions on this topic underline, the incredible success of the M5S and the League, together with the defeat of the mainstream parties, mixed up previous party bonds, redefining the social bases of different parties. Having won the support of a third of the electorate, it is inevitable that the basis of the M5S is rather heterogeneous, approaching the model of a ‘catch-all’ party. However, this does not mean that the M5S is equally attractive for all social groups. In particular, we observe a higher propensity to choose the M5S among young-adults (30–44 years old), blue-collar workers, unemployed, and voters living in the South.

The ability of the M5S to convince voters in situations of economic distress and those belonging to the most marginal sectors of the labour market has led to interpret its success, as for other similar challenger parties in Europe, as an effect of globalization and the economic crisis in post-industrial societies (Inglehart e Norris, Reference Inglehart and Norris2016). However, evidence from the data reported in particular by Vezzoni (Itanes) reveals that this interpretation is far from being appropriate. Data indicate that unemployment and the economy are still top priorities among public opinion, but their salience decreased between 2013 and 2018. Moreover, positive judgment about the Italian economy in general has increased from 2013. Voters' perceptions are in line with the macroeconomic data analysed by Capriati (CN), which show a slight recovery of the Italian economy between 2013 and 2018. Perceptions of personal economic distress indicate instead a more pessimistic picture of the Italian economy. However, voters who were perceiving a difficult economic situation – the so-called ‘losers from globalisation’ – were attracted not only by the M5S, but also by the League and FI, which according to this variable present a distribution similar to that of the M5S. In other words, perceptions of economic distress are not able to discriminate between voters of the M5S and centre-right parties. Still, they can be useful to distinguish the PD – the only party capable of attracting the support of the ‘winners from globalisation’ – from the other parties. This view clearly emerges not only from the contribution of Vezzoni (Itanes), but also from that of Ceccarini (BCD).

Bordignon (BCD) reports further evidence that speaks against the ‘economic interpretation’ of the success registered by the M5S. Tabulating the perceptions of economic distress by geo-political areas, the League is overrepresented in the North among voters that complain about their economic condition. In contrast, in the South – which reports on average a higher level of dissatisfaction in comparison with the rest of Italy – the M5S voters show a level of economic distress lower than the area average. A similar picture emerges from an analysis conducted by Cavallaro et al. (CDP), who study the distribution of votes across labour market geographical areas codified by ISTAT: the League was able to increase its votes particularly in the non-specialized labour market areas – which represent the less advanced areas in Italy. This analysis also highlights that the PD performed well mainly in those urban areas characterized by a high level of labour specialization. These data suggest the existence of a further social cleavage – in addition to the North-South one – opposing large cities and the rest of the country. Such territorial cleavages appear as something new in comparison with the 2013 election, and for this reason all the books under review stress their importance as a key element to interpret the 2018 election.

New issue cleavages?

An alternative account of the success of challenger parties in Europe suggests that it could be explained as a voters' reaction against progressive cultural and value change in the society, manifesting itself in an opposition to multiculturalism and immigration (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006). All survey data show a strong association between anti-immigration attitudes and the vote for the League and to a lesser extent for the M5S. This result appears particularly clear in the logistic models reported in the appendix of BCD. However, the success of the two challenger parties does not depend on a massive change in anti-immigrant sentiments among public opinion. Anti-immigration attitudes have been stable in the past five years: in 2018, as in 2013, most voters considered immigration as a major threat to the Italian culture, national economy and security. What changed in comparison with the past is the salience of the immigration issue, which in 2018 was perceived among the top priority problems, after unemployment. These variations in issue salience are well illustrated by Vezzoni (Itanes) and Emanuele et al. (CD). The salience of immigration, together with the fact that the League was identified as the most credible party on this issue, can therefore explain why so many voters cast their ballots for Salvini's party. It could be added that the success of the Lega is the product of a ‘herestetic’ manoeuvre successfully conducted by the leader of the League Salvini, aimed at strategically expanding the dimensionality of the space of competition by introducing new dimensions of conflict.

The rise of immigration and cultural issues is usually associated with the gradual decline in the importance of the classical left-right divide. New challenger parties share a post-ideological nature and the capacity to mobilize the electorate on new conflictual issues such as immigration. However, in 2018 Italian voters still paid attention to the left-right divide as most of them used these labels to place themselves on the political space. This holds also for M5S voters, despite the fact that the party stressed its post-ideological status more than its competitors. This paradoxical situation is discussed in the contribution of Baldassarri and Segatti (Itanes). Voters also used these labels to place parties on the left-right divide: only few voters declared that they were unable to classify parties according the left-right dimension and their number decreased in comparison with the 2013 election. Voters did not find difficult to place the M5S on the left right scale and they agreed in locating it in a neutral position at the centre of the political space. The positioning of the M5S – which, as outlined above, was able to attract votes from all the political spectrum – is probably the product of contrasting opinions of its voters on many issues. This might indicate that the left-right can be interpreted as a sort of ‘super-issue’ to which specific issues of the campaign are ideologically related. Being on the left and right, however, does not always lead to consistent opinions on these issues and this is especially true for voters on the left, especially in relation to immigration: on this matter, left wing voters had more heterogeneous opinions than right wing ones. This topic is prominent both in the contributions of Baldassarri and Segatti (Itanes) and Emanuele et al. (CD).

Another crucial topic related to the 2018 election is the issue of ‘populism’. Until now, I referred to the M5S and the League as challenger parties rather than populist parties, as populism is a vague concept easy to confuse to other related concepts (Rooduijn, Reference Rooduijn2019). Some of the contributors in the volumes under review adopted the same stance, while other authors explicitly referred to populism as a key feature to interpret the 2018 electoral outcomes. For those, the leading narrative is that the success of the M5S and the League was the product of two different populisms, one triggered by economic distress and the other by cultural attitudes. Cavazza et al. (Itanes) – using a series of indicators aimed at measuring populism – found that populist attitudes in the electorate were associated with the vote for the M5S and the League. However, regarding the League this association ceased to be significant once controlling for anti-immigration attitudes, meaning that the drivers behind the League populism were mainly cultural. About the M5S, as noted above, populism is associated neither with immigration nor economic distress. To explain the success of the M5S, a further element is crucial: the anti-political sentiment among public opinion that had grown stronger over the years. As it emerges from Itanes survey data and those analysed in BCD, the degree of voters' distrust towards democratic institutions and the processes of representative democracy indicates that another important cleavage emerged in the run-up to the 2018 election: the one separating the ‘mainstream’ from the ‘anti-establishment’ parties, among which the M5S was considered the most credible by voters due to its history. This interpretation clearly emerges in the introduction and the conclusion of the edited book by Ceccarini and Newell (CN), but also in the foreword of Diamanti (BCD).

Conclusion

In this review article, I offered an account of the most salient features characterizing the 2018 Italian election as they were highlighted by the contributors of the volumes examined here. I grouped those features using the conceptual framework based on the notion of critical elections. The picture originating from the volumes under review is not so sharp as that emerging from the literature that flourished after the 2013 election, whereas several contributions stressed the revolutionary traits of that electoral contest. Despite the several important changes observed in comparison with 2013, defining the 2018 general election as critical is adequate only to a certain extent. When examining the patterns of party competition, the 2018 outcome shows relevant but less revolutionary changes than those observed in 2013, when a new party – the M5S – all of the sudden succeeded in becoming the most voted party. In 2018, the League reported the most striking results, but its success can somewhat be read as an outcome of the internal dynamic within the centre-right pole. About the changing social bases of parties, the only indisputable result is the progressive detachment of the social classes traditionally belonging to the left from the PD. Whether or not those voters found a stable home in the M5S or the League is an open question. The authentic element of novelty in the 2018 election has to do with the issue space of political competition, as new policy and non-policy dimensions of conflicts were clearly detectable. Even though some of these new dimensions can be traced back to the classic left-right division, the new configuration of the issue space made feasible a government entirely formed by challenger parties such as the Conte government. In other words, as more or less explicitly stated in the volumes under review, the 2018 general election produced political consequences that can be interpreted as the end point of a process of electoral changes triggered by the 2013 election.

Two subsequent elections – such as that of 2013 and 2018 – characterized by high levels of volatility giving rise to an extremely rare dyad of volatile elections in Europe suggest a phase characterized by fluidity and uncertainty. Therefore, the open question is whether or not in 2018 we observed a further step towards a process of realignment, that could lead to stable patterns of party competition in the future, or we entered a new phase of deinstitutionalization of the party system. Still, the dissolution of the Conte government, the coalition agreement between the M5S and the PD, and the boom of the League in the polls seem to suggest that instability is likely to remain a characterizing trait of the Italian political system.