Article contents

Abstract

- Type

- Legislation

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press and The Faculty of Law, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem 1972

References

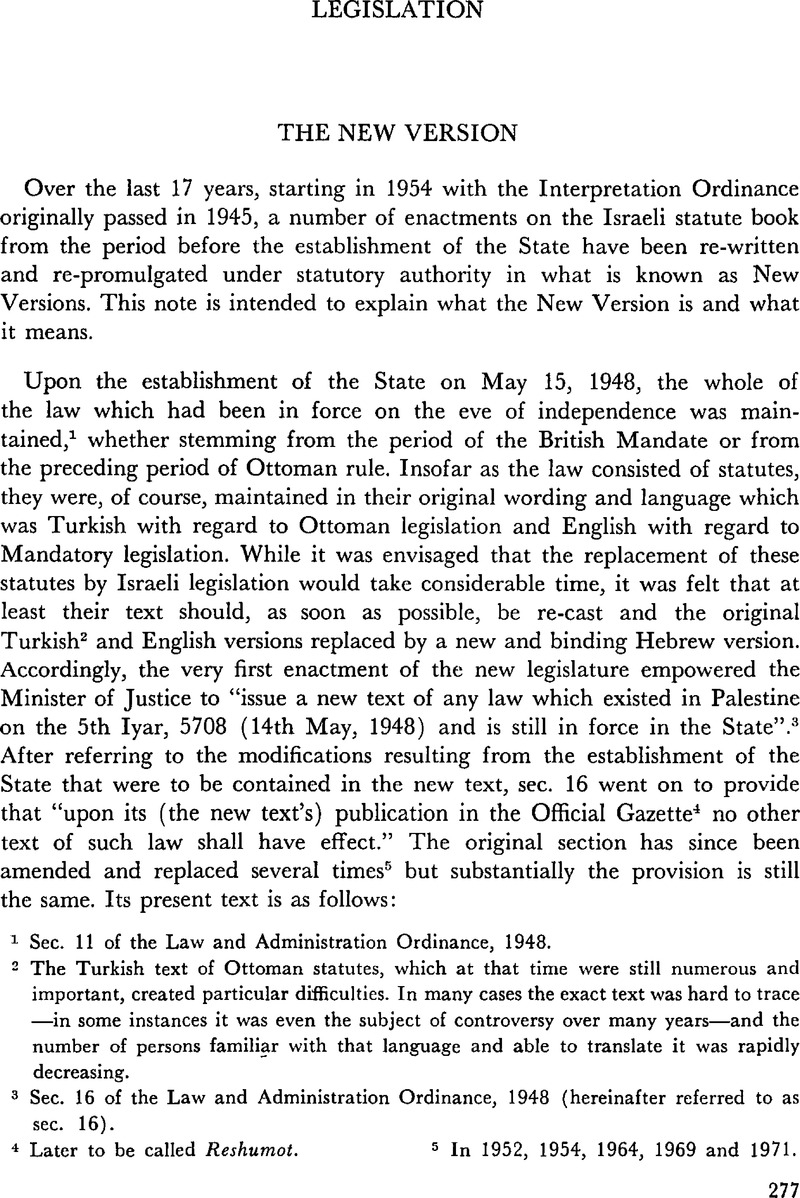

1 Sec. 11 of the Law and Administration Ordinance, 1948.

2 The Turkish text of Ottoman statutes, which at that time were still numerous and important, created particular difficulties. In many cases the exact text was hard to trace—in some instances it was even the subject of controversy over many years—and the number of persons familiar with that language and able to translate it was rapidly decreasing.

3 Sec. 16 of the Law and Administration Ordinance, 1948 (hereinafter referred to as sec. 16).

4 Later to be called Reshumot.

5 In 1952, 1954, 1964, 1969 and 1971.

6 This was the title of locally enacted primary legislation. At first it was used also for the enactments of the new Israeli legislature. Since the establishment of the Knesset, in 1949, its statutes bear the title of “Law.”

7 In distinction to certain Acts of the English Parliament and Orders-in-Council which applied in Palestine but were enacted in England.

8 Contrary to the arrangement, e.g., in Switzerland where the texts in the three official languages are of equal validity.

9 Sec. 34 of the Interpretation Ordinance, 1945 and since 1954 sec. 32 of the New Version of the Interpretation Ordinance.

10 Which constitutes the Israeli law of torts.

11 For the composition of this Board see text of sec. 16.

12 The government approves all Bills submitted on its behalf to the Knesset.

13 A Law of 1971 amending the Road Transport Ordinance, for instance, bears the name “Road Transport Ordinance (Amendment) Law, 1971,” but its provisions refer to and amend sections of the Ordinance as contained in the New Version.

14 There are at present law schools at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and at the Universities of Tel-Aviv and Bar-Ilan.

15 Some of them are verbatim copies of English Acts; others are statutory re-statements of English common law; others again are heavily influenced by English legal concepts.

16 Bills of Exchange Ordinance, Civil Wrongs Ordinance, and among those not yet “transformed” into New Versions, the Criminal Code Ordinance, the Bankruptcy Ordinance and the Companies Ordinance.

17 The formula here quoted is that of the Companies Ordinance, 1929. In other Ordinances of this group the formula employed is more detailed; but they are all to the same effect.

18 For details of the conflicting arguments, see Klinghoff er (the chairman of the subcommittee mentioned above) “Compulsory Reference to English Terminology in the New Version of Mandatory Statutes” (1969) 1 Mishpatim 440.

19 There is now under consideration a Bill for the amendment of the Civil Wrongs Ordinance, and others, with a view to “liberating” them from the “compulsory reference” to English law. The Bill refers both to Ordinances now applying in New Versions and those still applying in the original one.

20 For the implications of art. 46, see, among others, Ginossar, S., “Israel Law: Com ponents and Trends” (1966) 1 Is.L.R. 380.Google Scholar

21 This new legislation has so far covered—in chronological order—capacity and guardianship, succession, agency, guarantee, pledges, bailment, sales, gifts, transfer of debts, the law of immovables, remedies for breach of contract, the law of movables and hire.

22 Such clauses are contained in the Succession Law of 1965, the Law on Immovables, 1969 and the Law on Remedies for Breach of Contract, 1970; but it is believed that the same measure of independence from English law has also been achieved in the enactments of this series which do not proclaim it expressly. On this point see Yadin, , “How is the Law of Bailment to be Interpreted?” (1968) 24 HaPraklit 493.Google Scholar

23 In 1971, a special amendment of sec. 16 was enacted to make it clear that a “new text” may be issued not only with regard to a whole statute but also with regard to part of it. The General Part of the Criminal Code Ordinance is at present before an advisory committee with a view to replacing it by a new law.

24 The dilemma caused by the interpretation clauses may also be solved by simply repealing them. See supra n. 19.

25 On this point see Yadin, , “On the Interpretation of Laws of the Knesset” (1957) 13 HaPraklit 305, 314–5Google Scholar, and “Once more on the Interpretation of Laws of the Knesset” (1970) 26 HaPraklit 190, 358, 371–374.

26 Some writers have expressed contrary views.

27 State of Israel v. Haas (1961) 15 P.D. 2193, 2206; Isramah v. State of Israel (1968) (I) 22 P.D. 343, 361; Neuman v. Cohen (1971) (II) 24 P.D. 229, 240.

28 Assessing Officer of Tel Aviv v. Mazal (1966) (II) 20 P.D. 695, 698. See also Tedeschi, , “Taking Part in Another's Tort and Pitfalls of the ‘New Version’” (1968) 25 HaPraklit, 59.Google Scholar

29 The New Version of the Criminal Code Ordinance—Special Part may belong to this combined category.

30 They are published in the Sefer HaHukim.

31 The way of replacement was adopted in some cases, such as the Courts Law, 1957, which took the place of the Courts Ordinance, 1940.

32 Introduction of a Bill, three readings, signature by the President of the State, etc.

33 In certain matters, if and so far as a law empowers them to do so, Ministers may make new laws by means of secondary legislation. Thus, the rules of civil procedure are established by Rules of the Minister of Justice.

- 3

- Cited by