Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 February 2016

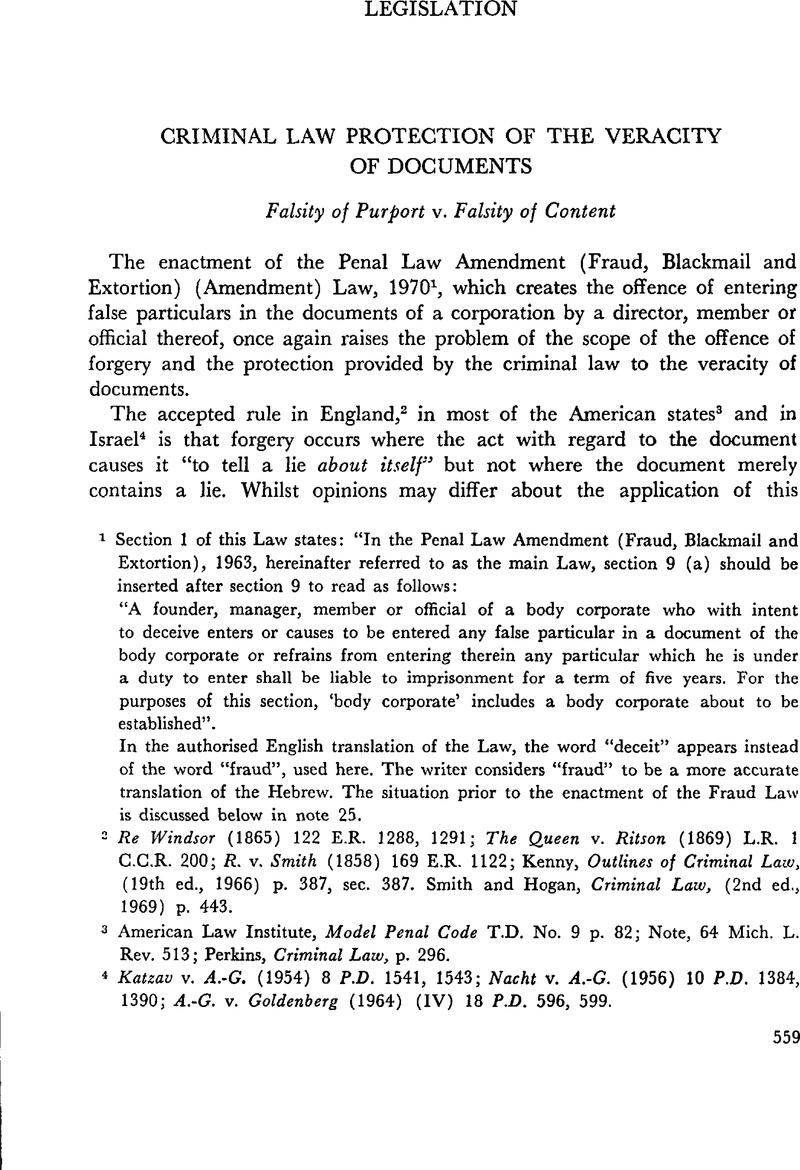

1 Section 1 of this Law states: “In the Penal Law Amendment (Fraud, Blackmail and Extortion), 1963, hereinafter referred to as the main Law, section 9 (a) should be inserted after section 9 to read as follows:

“A founder, manager, member or official of a body corporate who with intent to deceive enters or causes to be entered any false particular in a document of the body corporate or refrains from entering therein any particular which he is under a duty to enter shall be liable to imprisonment for a term of five years. For the purposes of this section, ‘body corporate’ includes a body corporate about to be established”.

In the authorised English translation of the Law, the word “deceit” appears instead of the word “fraud”, used here. The writer considers “fraud” to be a more accurate translation of the Hebrew. The situation prior to the enactment of the Fraud Law is discussed below in note 25.

2 Re Windsor (1865) 122 E.R. 1288, 1291; The Queen v. Ritson (1869) L.R. 1 C.C.R. 200; R. v. Smith (1858) 169 E.R. 1122; Kenny, , Outlines of Criminal Law, (19th ed., 1966) p. 387Google Scholar, sec. 387. Smith, and Hogan, , Criminal Law, (2nd ed., 1969) p. 443.Google Scholar

3 American Law Institute, Model Penal Code T.D. No. 9 p. 82; Note, 64 Mich. L. Rev. 513; Perkins, Criminal Law, p. 296.

4 Katzav v. A.-G. (1954) 8 P.D. 1541, 1543; Nacht v. A.-G. (1956) 10 P.D. 1384, 1390; A.-G. v. Goldenberg (1964) (IV) 18 P.D. 596, 599.

5 In section 1 of the Penal Law Amendment (Fraud, Blackmail and Extortion) Law, 5723–1963 (hereinafter the Fraud Law), the formulation appears generally in section 1 (1) and details are subsequently given of the major situations included within this formulation.

6 Smith and Hogan, op. cit., p. 448; Kenny, op. cit., p. 389, sec. 389; Perkins, op. cit., p. 297; sec. 1 (3) of the Fraud Law.

7 The Queen v. Ritson (ubi supra); R. v. Riley [1896] 1 Q.B. 309.

8 Kenny, op. cit., p. 390 sec. 392.

9 Perkins, op. cit., p. 297; Kenny, op. cit., p. 390, sec. 391; sec. 1 (2) of the Fraud Law, (definition of forgery).

10 The local law is apparently wider and also includes the situation in which the changes are made by the person authorised to make them if the act was done with intent to defraud. See sec. 1 (2) of the Fraud Law.

11 There is, however, the view that when a person enters a false particular in a document, he acts in excess of his authority. See notes 26 and 28 below.

12 Burdick, , Law of Crime, Vol. 2, p. 516Google Scholar, sec. 651; p. 517, sec. 653; Kenny, op. cit., p. 379, sec. 372.

13 Kenny, op. cit., p. 379. There is an interesting resemblance to the development of the offence in Germany where in the early stages the emphasis was also laid on the form of the document: Maurach, , Deutsches Strafrecht (4th ed. 1964) Vol. 2 Besonderer Teil p. 449Google Scholar.

14 Burdick, op. cit., Vol. 2, p. 515 sec. 651.

15 Ibid., p. 516, sec. 651; Concise Oxford Dictionary (forgery). In Hebrew as well, forgery has a similar meaning; according to the new Evan-Shoshan dictionary, the meaning of forgery is, “imitation with the intent to defraud”.

16 See sec. 1 of the Fraud Law.

17 In Israel there is a tendency on the part of the courts to widen the application of attempt. This appears from the Supreme Court case of Weidenfeld v. A.-G. (1966) (I) 20 P.D. 7, 23. The preparation of a document including a false declaration which was intended to be used for purposes of fraud was held to be attempted fraud. The Model Penal Code, Proposed Official Draft also recommends, in sec. 5.01, a formula which expands the boundaries of attempt to include the very making of a document containing false particulars for the purposes of fraud.

18 Cf. Maurach, op. cit., p. 451.

19 See the present author in (1969) 26 HaPraklit 85.

20 See the Comments in the Model Penal Code Tentative Draft No. 11 p. 79.

21 See, for example, secs. 383–4 of the Ethiopian Code of 1957, secs. 288–9 of the Roumanian Code of 1969, and Maurach, op. cit., pp. 449, 450, 458, and particularly 467. See also the laws of the countries mentioned in note 30 below.

22 (1957) 41 Cr. App. Rep. 231.

23 The case has been criticised on the grounds that it is inconsistent with the wording of the Forgery Act, 1913 (as amended by the Criminal Justice Act, 1925). See, for example, Note in (1957) Crim. L. R. 809 and also Kenny, op. cit., p. 388. It is not relevant for present purposes to determine to what extent this criticism is justified. All that needs to be observed here is that the facts of life apparently led the court to give an expansive interpretation to forgery. Further, if less extreme, examples of such interpretation may be found in rulings which held that the offence includes the making of a document which purports to be a copy of an original which did not exist: Gurevitch v. A.-G. (1959) 13 P.D. 377 (Olshan P. and Goitein J. with Silberg J. dissenting); the signature of a correct name on a cheque drawn on a bank which did not exist, in re Clemons 151 NE (2d) 553 (1958). In the latter case, the law dealt not only with forgery but also with “false making” in which the court saw indications of the desire of the legislature to expand the limits of the offence.

24 See text of sec. 1 of the Law, n. 1 above.

25 Prior to the enactment of the Fraud Law, equivalent provisions existed in secs. 313(b)(ii) and (iii) and sec. 314 of the Criminal Code Ordinance, 1936. See also the repealed sec. 315 of the Ordinance which dealt with the liability of officials (not necessarily of companies) who made a false entry or omitted a material particular from a record book or account. Sec. 316 of the Ordinance, also repealed, dealt with the liability of government officials furnishing false statements, and sec. 347, also repealed, with the liability of a person having custody of any register or record who knowingly permits any false entries to be made. It is not clear why the Israeli legislature saw fit to repeal these provisions without providing at the same time a suitable substitute. It took seven years for the legislature to realize the void created by the repeal of the above sections. In England as well, there is specific legislation on the point. See, for example, the Falsification of Accounts Act, 1875, the provisions of which were absorbed with certain changes in secs. 17–20 of the Theft Act, 1968.

For examples of American legislation, see the New York Statute discussed in the English case, R. v. Windsor (1865) 122 E.R. 1288. See also sec. 889 of the California Criminal Code and sec. 943.39 of the Wisconsin Criminal Code. For the various approaches to forgery in the cases and legislation of the various American States, see Note (19), 64 Mich. L. Rev. 513, 514.

26 (1963) 17 P.D. 199, 205.

27 Following is the text of sec. 344(a) of the Criminal Code Ordinance which has since been repealed by the Fraud Law:

“344. Any person who, with intent to defraud:

(a) without lawful authority or excuse, makes, signs, or executes for or in the name or on account of another person, whether by procuration or otherwise, any document or writing… is guilty of a felony and is liable to imprisonment for seven years.”

28 See the similar approach of the Illinois court in the case of People v. Mau 36 N.E. (2d) 235.

29 Sec. 1, Fraud Law. Inexplicably this definition does not appear in the authorised English translation of the Law.

30 In the Argentine Criminal Code, “intellectual” forgery relates only to official documents (sec. 293) or medical certificates (sec. 295). Likewise in the Turkish Code “intellectual” forgery relates only to official documents (secs. 340; 342) or the making of a false declaration to a public official (sec. 343), while with private documents forgery is applied in its narrow meaning (sec. 345). The same is also the case with the Norwegian Code, where “intellectual” forgery relates only to official documents (sec. 189). The foregoing is based upon the texts of the codes translated into English and published by the America Series of Foreign Penal Codes (New York University). In the Austrian Criminal Law the application of “intellectual” forgery is much narrower than that of “material” forgery. Rittler Lehrbuch des Oestrreichisches Strafrecht, Vol. II, 450. The same is true of German Law. Maurach, op. cit., p. 458.

31 See the definition in the case of Katzav v. A.-G. (1954) 8 P.D. 1541, 1543–4. Cf. also Rittler, op. cit., p. 439.

32 See Baron Parke's dicta in Irish Society v. Derry, quoted in Cross, Evidence (3rd ed.) p. 428. The concept of “official document” for the present purposes is not altogether identical with the law of evidence concept of “public document”, which is narrower and relates only to documents open to the public. The distinction, however, will not be gone into in this note.

33 Sec. 106 of the Companies Ordinance. See also the provisions of the Law cited in n. 1 above.

34 Sec. 25, Pharmacists Ordinance. A general provision prohibiting the inclusion of false particulars in documents required to be kept by law for the purpose of control is to be found in sec. 484 of the Italian Code of 1930. Sec. 353 of the Turkish Code also creates the offence of registering false particulars in books required to be kept by law in connection with a business or profession. Cf. sec. 154 of the French Code and sec. 397 of the Korean Code 1953.

35 Sec. 23(1), Pharmacists Ordinance|

36 Cf. the American case of People v. Klein, 258 N.Y. (2d) 783. For Israel, see A.-G. v. Sternberg (1956) 25 P.E. 201 (the accused was not charged with forgery).

37 Sec. 14B of the Evidence Ordinance provides that a copy of an entry in a banker's book shall be prima facie evidence “of the matters, transactions, or accounts therein recorded”. Sec. 390 of the Ethiopian Code creates the offence of giving false information in a bank certificate, such as a deposit of shares certificate, etc.

38 In Israel, criminal liability is imposed for the delivery of a false medical certificate under sec. 113 of the Criminal Code Ordinance. This refers generally to the delivery of a false certificate by a person entitled or required to give a certificate dealing with a matter which may affect the rights of any person. (See Kelly v. A.-G. (1958) 34 P.E. 197). In many countries there are special provisions dealing with false medical certificates. See, for example, sec. 395, Ethiopian Code; sec. 295, Argentinian Code; sec. 318, Swiss Code; sec. 180, Norwegian Code; secs. 159–160, French Code; sec. 233, Korean Code.