Introduction

Assyriology’s main objective is, as it was once put, “the recovery and reconstruction of a lost heritage” (George Reference George1997: 73a). Because of their profound impact on ancient literature and individuals, recovering the classics of ancient Babylonia – the texts that the literate population read, memorized, and cited – can significantly advance this goal: when a classic is recovered, not only is its text regained, but also the dense network of quotations, allusions and excerpts that show how the Babylonians responded to it.

The text published here for the first time can be added to the small cadre of compositions one may call “classics”: preserved in no fewer than 20 manuscripts, from the 7th to the 2nd/1st centuries BCE, it was a fixture in the school curriculum of the time.Footnote 1 Presumably literate Babylonians knew the text by heart, since school texts were wholly or partially committed to memory,Footnote 2 and indeed quotations of it can be found in other texts.Footnote 3 It contains unparalleled descriptions of the healing powers of Marduk, the splendor of Babylon, the spring borne by the Euphrates to the city’s fields and — most extraordinary of all — the generosity of the Babylonians themselves. The author of this highly accomplished piece immortalized his devotion to his city, gods, and people in words that resonated until the final decades of cuneiform culture.

1. Contents and Exegesis

About two-thirds of the original text, which may have been 250 lines long, have been completely or partially recovered.

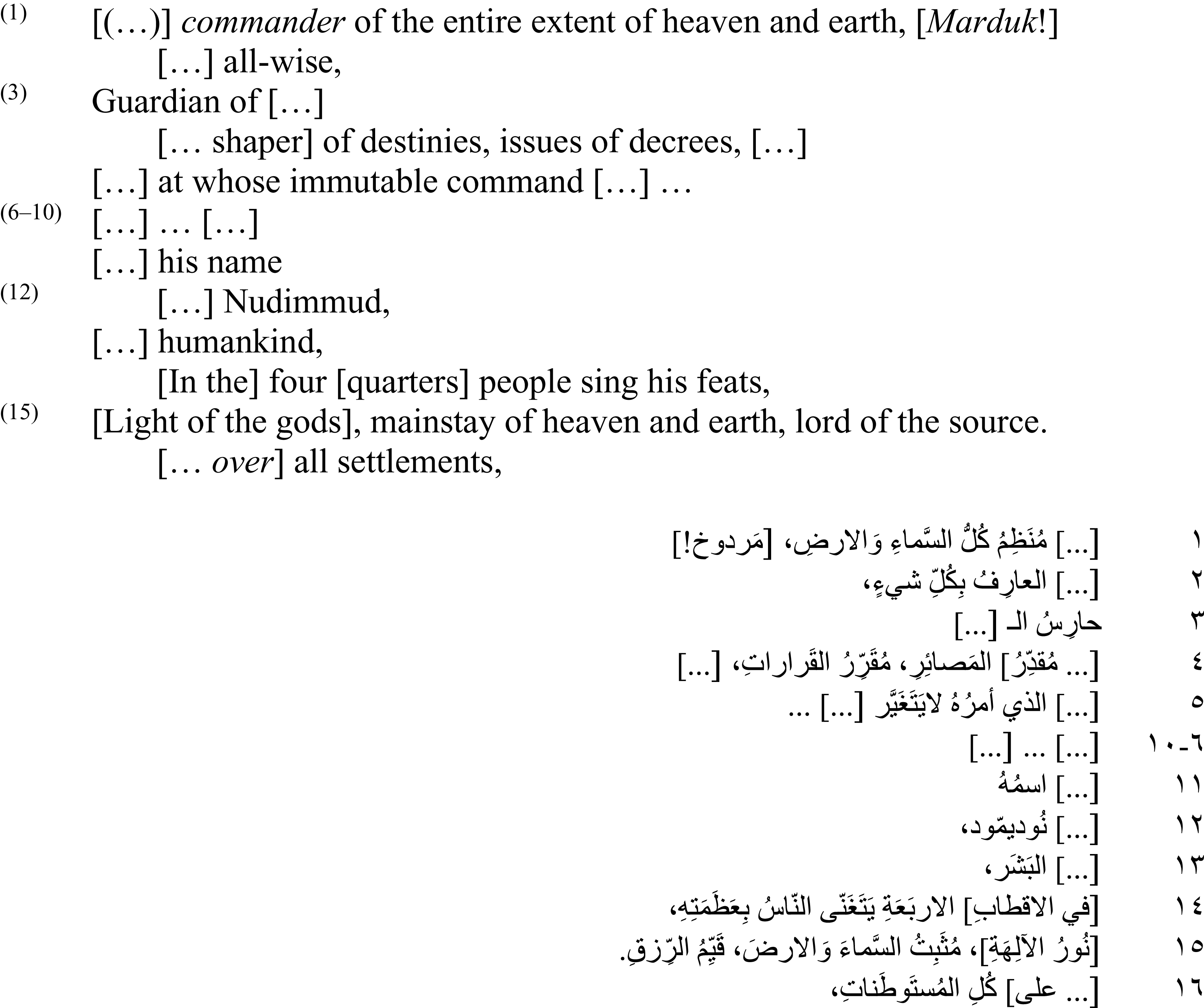

§1. Opening Hymn (1–25). The poem opens with a hymn to Marduk, formulated in the third person, which lists epithets from the standard repertoire, along with some unique ones (such as “guardian spirit of Esagil,” l. 20), and ends with a stanza of the AA′B type (ll. 23-25).

§2. Hymn of God to Marduk (26–79). A formula introduces the speech of a god, who in all likelihood addresses Marduk. The speech in question is a long hymn, much more sophisticated than the previous one. Some of the lines of the text are reminiscent of the “great hymns” to Marduk, and indeed l. 39 appears verbatim in ‘Marduk 2’. The hymn traverses several realms in which Marduk’s help is providential, such as financial loss (50f.) and provision of food and shelter through vegetation (69–72). The final segment of the hymn presents the waters, whose dominion Marduk inherits from his father Ea, as the nourishers of all creatures; with these waters are mixed (summuḫu) fire and air (75f.). Why these three elements are mentioned only becomes somewhat clear later. Before, in an unparalleled passage, the “gods of the land” (i.e. the lower gods), are presented as standing as “their servants” (dāgil pānīšunu), i.e. as the servants of the waters or else of the three elements mentioned (l. 77). In the awesome presence of Marduk they do not dare to speak (l. 78f.); they “take counsel with each other” (l. 80f.). Then the action for which the assembly has been convened takes place: the three great gods (Anu, Enlil, and Ea) and their consorts “bless” (ikarrabū, note the present tense) Marduk. This event reveals the importance of the mention of the three elements water, fire, and air earlier: according to a Babylonian doctrine, these are the three primordial elements. In the syncretistic hymn to Marduk ‘Eriš šummi’, water and fire (“air” is mentioned earlier) “support” (ukallū) life, i.e., they make it possible.Footnote 4 In the Babylonian view, the triad Anu-Enlil-Ea represents these three elements: thus, in the commentary 1881,0204.419 ll. 6′–8′ (eBL transliteration: Stadhouders):Footnote 5

The three basic constituents of the universe (fire, air, and water) are, therefore, associated with Anu, Enlil, and Ea. The three elements, to which the “gods of the land” stand in service, are the cosmogonic counterparts of Anu, Enlil, and Ea.

§3. Hymn to Esagil (86–99). The blessing to Marduk is followed by a hymn to his temple, Esagil, which is “beautiful” (or “built,” banû, s. commentary). A number of epithets are showered on Esagil, some of them etymologically derived from the name of the temple and known in other treatises devoted to it. Esagil is “Eridu” (for that is the name of the neighborhood where it is located), it is the gateway to the Apsû and the underworld, and it is built with mysterious and subtle artistry.

§4. Hymn to Babylon (100–124). The literary caliber of the text increases when it reaches the section dedicated to Babylon, the city whose “ordinances are perfect” (l. 100). After identifying Eridu with Babylon (“It is called Eridu, Babylon is its name”), the city is described as a hoard of precious stones of all kinds (ll. 105–108). Babylon “flourishes in her charms” like a fruit garden (l. 109). After this description, the different components of the city are introduced. First, its star, the “star of Marduk” (i.e. Nēberu); then its “gate” and its wall, Imgur-Enlil; and, most arrestingly, its king, Alulu (l. 115). In Mesopotamian tradition, Alulu was the first king, and he reigned in the city of Eridu. That he should be described as king of Babylon in our text is not altogether surprising: according to Berossos, “Aloros (῎Αλωρος), a Chaldaean from Babylon, was the first king and he reigned for ten saroi” (De Breucker Reference De Breucker2012: 232). Our text thus shows that the tradition recorded by Berossus is also present in cuneiform texts.

The next element of Babylon to which the poet directs his attention, its river, triggers a lyrical torrent describing the arrival of spring – a gift of the Euphrates – to the fields of Babylon (ll. 116–124). The water makes the fields bloom, the grain sprout, and the flocks graze on it.Footnote 6 Mesopotamian literature is sparing in its descriptions of natural phenomena; in particular, only one other lengthy description of the coming of spring seems to exist, in the cosmogonic prologue to ‘Ox and Horse’ (s. below, Genre).

§5. Hymn to the Babylonians (125–158). The poet now turns his attention to his fellow citizens, “the clan of Lugal-abzu,” the “progeny of Alalgar” (125, 127, Alalgar being the successor of Alulu as king of Eridu in the Mesopotamian tradition). The “free citizens” (ṣābū kidinni) of Babylon are, for the author of this hymn, in essence the priests of Babylon — an indication that its author probably was a member of this class. The Babylonians are fair, protect the orphan and the humble (ll. 136–138), follow the divine precepts and keep justice (l. 141); in particular they abide by “the original stele, the ancient law,” perhaps a reference to an actual stele, such as Hammurapi’s. They respect one another, please each other (ll. 146f.) and –strikingly– respect the foreigners who live among them. The concept of respecting the foreigners has, of course, Biblical connotations,Footnote 7 although in our text the foreigners referred to are specifically the foreign priests living in Babylon.

After the Babylonian men, the text pays attention to the Babylonian women, whose quintessence are the Babylonian priestesses. The passage has great importance for understanding the roles played by the various classes of priestesses: ugbakkātu, nadâtu, and qašdātu. The priestesses are particularly virtuous but, in contrast to the active role of men in protecting the helpless, the main virtue praised in women is devotion and discretion. The hymn to the Babylonians ends with the doxology: “These are the ones freed by Marduk” (šunū-ma šubarrû ša marūtuk, l. 159).

§6. Broken section (159–end). About one hundred lines of the ending are missing or mutilated; it is difficult to ascertain what they might have contained. Since the end of the third column (ll. 191–198) refers to goods granted to a multiplicity of persons, it is possible that the hymn to the Babylonians continued for some 40 more lines. The beginning of the fourth column (ll. 204–211), by contrast, seems to describe the awe-inspiring appearance of a warrior god, perhaps Marduk, and his steeds.

2. Genre

The incipit of the text, not yet fully recovered, reads: […] nagbi šamê u erṣ[eti marūtuk (?)]. The title appears to be absent from catalogues and tablet inventories. It is possible, however, that this title appears in the catchline of the main manuscript of the ‘Hymn to Šamaš’, K.3182+ iv 34 (NinNA1 in Rozzi Reference Rozzi2021): [o o o o o o o o o o a]n-e u ki-t[ì o o o]. Although the phrase “heaven and earth” is, of course, very common, both the incipit of the present text and the catchline have erṣetu as the penultimate word, which makes the identification plausible. At least some of the great hymns were linked to each other by means of catchlines, forming a series: thus, the catchline of several tablets of ‘Marduk 1’ links to the ‘Hymn to Šamaš.’Footnote 8 If correctly identified, the sequence in the series would be ‘Marduk 1’ → ‘Hymn to Šamaš’ → our text.

In any case, the text is clearly hymnic in character, like the other “great hymns” with which it is perhaps linked. One feature of the text, however, is not typical of hymns: after the initial praise, the text contains a speech introduction formula (ll. 26f.: [… pâšu] īpuš-ma iqabbi | [… šam]ê u erṣeti amāta izakkar), followed by a speech of one god, at the end of which the great gods bless Marduk. These introduction formulae are known almost exclusively in narrative poetry and in parodies thereof.Footnote 9 They also appear, however, in the mythological sections of two Old Babylonian hymns.Footnote 10 The occurrence of the formula suggests that the present text also represents a sort of hybrid between hymn and mythological narrative composition.

Other elements of the text suggest that the events that appear in it are situated not in the atemporal plane of the hymns, but rather in illo tempore, in the mythological time immediately prior to the beginning of history.Footnote 11 On the one hand, human kings appear, albeit they are the first two kings of the Mesopotamian tradition, Alulu and Alalgar (ll. 115 and 126). On the other, each of the sections begins with a reference to creation: Esagil is “created” (banû, l. 86, s. commentary ad loc.), and “was created” (ibbanû) in the city of Babylon (l. 100), alongside which the Babylonians were also “created” (ibbanû, l. 127). Thus, the text seems situated at the dawn of history, in the moments following creation. As in the historiola ‘The Founding of Eridu’,Footnote 12 the text seems to assume that the first entities to be created in the universe were Eridu/Babylon and Esagil. As in other Mesopotamian texts, the dawn of the story takes place at the dawn of the year, in the spring,Footnote 13 brought to Babylon by the waters of the Euphrates.

⁂

Hymns to cities and temples are, as noted by A. R. George (Reference George1992: 3), much less popular in Akkadian literature than they are in Sumerian. Although the number of manuscripts of the present text shows that at least this hymn gained considerable popularity, few other Akkadian texts are known which have such a detailed description of a city, its temples, and its gods. Perhaps the most notable parallel is constituted by a hymn to Borsippa known on two three-column tablets, which has certain parallels with the present text (see comments on ll. 52 and 136).Footnote 14

3. Date

The precise dating of this text, as is often the case with literary works, remains elusive. The terminus ante quem is marked by the earliest surviving manuscript (AssSchNA1), a tablet from the Assur school devoid of precise archaeological context but datable to around the 7th century BCE. Moreover, its adoption as a school text implies a prior period of circulation preceding its incorporation into the curriculum. As for the terminus post quem, the lack of Old and Middle Babylonian manuscripts, if this silence is indeed indicative, hints at a composition date sometime after the first half of the second millennium BCE. The text resonates with the ideology characteristic of the “Rise of Marduk,” placing it potentially within the same timeframe as other works incorporated into the “Marduk Syllabus,”Footnote 15 such as ‘Enūma eliš’ or ‘Ludlul’, i.e. in the second half of the second millennium BCE. Yet, the paucity of reliable chronological anchor points makes a precise dating of these texts no trivial task either.Footnote 16

As stated above, the text is set at the beginning of history, so few elements can be extracted from it that would allow its dating. The fact that it mentions Nippurean and Susian priests living in Babylon (l. 134) could suggest that the text was composed in the Kassite period, during which time expatriates from both places are documented living in Babylon.Footnote 17 The description of the kind treatment of Elamite expatriates by the Babylonians would seem unlikely after the beginning of the Elamite invasions of Babylon during the 13th century BCE.

4. The Manuscripts

Although none of the colophons of the manuscripts of this text are fully preserved and the provenance of most of them can be determined only approximately, two clear groups can be established on the basis of the paleography and orthography of the manuscripts: Neo-Babylonian and Late Babylonian manuscripts. The excerpts from the text on school tablets constitute a third group, more miscellaneous than the other two.

Group 1: Neo-Babylonian Manuscripts

The first group consists of tablets datable to the ‘long sixth century’, i.e. between the rise of the Neo-Babylonian dynasty in 626 BCE and the ‘End of Archives’ in 484 BCE. The Sippar tablets of this period compete in quality and reliability with the often-praised manuscripts from Nineveh. MSS SipNB1, SipNB2, SipNB3, and SipNB4 come from Sippar; they all divide the text into 2 columns per side. The most important manuscript of the text, that of the Sippar Library (MS SipNB1), consists of two fragments found, according to the excavation record, in two different niches: IM.132512, from niche 7 D (1), and IM.132667, from niche 6 D (1).Footnote 18 The Sippar Library tablet divides the lines into two halves, which generally correspond to the two hemistiches of the verse: the vertical line thus marks the caesura.Footnote 19 This “finesse of the scribal art” (Lambert Reference Lambert1960a: 66 fn. 1) is found only in a few Neo-Babylonian copies of literary texts.Footnote 20 The tablet also includes decimal markers every ten lines, and twice every five lines (ll. 85 and 95). MS SipNB2 and SipNB4, both belong to the British Museum’s “Sippar Collection” and derive in all likelihood from that city.Footnote 21 SipNB2 seems to derive from the same archetype as SipNB1: the spellings are very similar, and very few variants exist. SipNB3, in the Istanbul Sippar collection, is similar to other fine two-column Neo-Babylonian literary manuscripts that derive from J.-V. Scheil’s excavations at Sippar, such as Si.15 (‘Hymn to Šamaš’, Lambert Reference Lambert1960a, pls. 33 and 36) and Si.851 (‘Marduk 2’, CTL 1, 100).

Of the Neo-Babylonian tablets from Babylon, BabNB1 is a two-column tablet written in a particularly small script. Slightly larger, but still relatively small is the script of BabNB2, a fragment that appears to belong to a single-column tablet, but whose surface has sustained extensive damaged. The obverse of the tablet, where only a few signs can be identified with certainty, does not seem to match the known text, its reverse ends abruptly at l. 123, followed by a ruling and by what appears to be a colophon: either the manuscript is part of an edition that divides the text into several tablets, or it is an excerpt on a school tablet. Even more damaged is the obverse of BabNB3, which seems to contain the beginning of the text, without this identification being certain. Its reverse, better preserved, cannot be matched with the known text, and the fact that its l. r 3′ mentions Ea, Šamaš, and d asar-lú (apparently not -ḫi) suggests that it may contain an entirely different composition. The consignment of BabNB1 and BabNB2 (80-11-12) comes almost entirely from Babylon, that of BabNB3 (81-7-1) contains many tablets from the same city (Reade apud Leichty Reference Leichty1986: xxx).

Group 2: Late Babylonian Manuscripts

Three tablets (BabLB1 to BabLB3) can be dated to the last centuries of cuneiform culture, perhaps specifically to the second or first centuries BCE. The criteria for dating the tablets to this period are, first, paleographic: the manuscripts exhibit the sign forms that are normally associated with the terminal phase of cuneiform, such as ku, lu, lagab, and ezen bereft of an upper horizontal wedge;Footnote 22 lul as dumu+pap (80 BabLB1); and az and uk with za and ud, respectively, added after the sign, rather than inscribed (38 and 46 BabLB2). The orthography of the manuscripts is also indicative of a late date: BabLB2 uses the sign ma k (ma5 = ka×éš) syllabically, which is attested only in a handful of late manuscripts (Frazer Reference Frazer2020). The late period also develops some ligatures that are absent from earlier manuscripts, most relevantly those of dumu×sal (on which see Jiménez Reference Jiménez2020: 242) and zu×ab (in l. 88, MS BabLB1). In addition, BabLB1–3 are the only ones to use bàd as determinative for the Imgur-Enlil wall in l. 114, a feature reminiscent of the use in Hellenistic and Parthian manuscripts of redundant logograms, such as lú šeš and lú ìr (in earlier periods simply šeš and ìr, see Jiménez Reference Jiménez2017: 346). The consignment of the tablets is compatible with a late date, since both the Spartali collection (BabLB2 and BabLB3) and 81-7-1 and 81-7-6 (BabLB1) contain many tablets, especially astronomical ones, from the Hellenistic and Parthian periods, many of them from Esagil.Footnote 23 Interestingly, BabLB2 and 3 share the odd spelling kurun.nam instead of gurrunu in l. 121 (BabLB1 is broken here), suggesting that they derive from the same archetype.

These three manuscripts testify to the popularity of the hymn in the waning decades of cuneiform, when Babylon, once a gem-laden mountain (ll. 105ff.), had faded into the semi-deserted city famously described by Pliny the Elder (Naturalis Historia VI 122). In this stark setting, Babylonians faithfully copied the hymn that spoke of the vanished glories of their city, the first of all creation.

Group 3: School Tablets

The only manuscript from Assyria (AššNASch1) is a school tablet with a selection of long excerpts from different texts (our text, ‘Hymn to Šamaš’, ‘Marduk Hymn 2’, ‘Erra Epic’). Although its first editor “saw nothing impossible in the inclusion of the four excerpts consecutively” in his edition of the ‘Erra Epic’ (Lambert Reference Lambert1980: 95), most subsequent scholars have noted that the first excerpt belonged to a text in honor of Babylon, and have described it as a text whose lines “praise the ideal of the šubarrê ša Marduk (= citizen of Babylon)” (Landsberger/Jacobsen Reference Landsberger and Jacobsen1955: 21 fn. 26), as a “Preislied auf Babylon” (Borger Reference Borger1967: 102), as “a hymn in praise of Babylon, probably of Middle Babylonian origin” (Lambert Reference Lambert and Haas1992: 143), and a description of “die gerechten Babylonier” (Maul/Manasterska Reference Maul and Manasterska2023, no. 33). The tablet’s high-quality writing suggests the work of an advanced scribe. The presence of a colophon, a rare feature in school tablets, further supports this interpretation.Footnote 24 The tablet contains, in this and the other excerpts, a few Assyrianisms,Footnote 25 and in the ‘Marduk 2’ excerpt in particular, quite a few corruptions.

School tablets with excerpts are, due to the trying character of their writing, more difficult to classify palaeographically than “library” manuscripts. Those from Babylonia are classified in the list of manuscripts according to the museum collection to which they belong, into Neo-Babylonian tablets from Sippar (SipNBSch1-3) and from Babylon (BabNBSch1-7); some of the latter, e.g. BabNBSch6, may also be Late Babylonian.

5. List of Manuscripts

Fig. 1. SipNB1 obverse. Copy by Anmar A. Fadhil

Fig. 2. SipNB1 reverse. Copy by Anmar A. Fadhil

Fig. 3. SipNB1 obverse. After conservation by C. Gütschow in November 2021

Fig. 4. SipNB1 reverse. After conservation by C. Gütschow in November 2021

Fig. 5. SipNB1 obverse (IM.132667 only). Shortly after excavation. No old photograph of the reverse seems to have survived

Fig. 6. SipNB1 (IM.132512 only). Shortly after excavation

Fig. 7. SipNB2, SipNB3, and SipNB4. Copies by E. Jiménez

Fig. 8. BabNB1, BabNB2, and BabNB3. Copies by E. Jiménez

Fig. 9. BabLB1. Copy by E. Jiménez

Fig. 10. BabLB2, BabNBSch2, and BabNBSch3. Copies by E. Jiménez

Fig. 11. BabNBSch6, BabLB3, and SipNBSch1. Copies by E. Jiménez

Fig. 12. SipNBSch2 and SipNBSch3. Copies by E. Jiménez

6. Fragments Potentially Belonging to Unrecovered SectionsFootnote 30

BM.38076, BM.39161+, BM.39252, BM.39269, BM.40328, BM.43372, BM.46177, BM.46197, BM.46823, BM.72061 a, BM.72135, BM.76021, BM.76244, BM.76769, BM.76996, BM.114741

7. Edition

8. Commentary

-

1. As noted above (§4 The Manuscripts), the deteriorated condition of the surface of BabNB3 makes it difficult to confirm its association with this composition. If true, MS BabLB1 would contain a bound form in -i (nagbi, on these forms, see George Reference George2003: 432f.), while BabNB3 would contain the normal form (nagab). It is unclear how many signs are missing after erṣeti, but is seems clear that there must be at least one word missing, since otherwise BM.42723 would join BM.45986 directly. Moreover, érṣetu is not acceptable as the last word in a line of poetry, since it would produce a non-trochaic ending. The reconstruction of Marduk’s name at the end is hypothetical;Footnote 42 alternatively one could read [(d)]⸢mes⸣ at the beginning, which would exclude the adopted reconstruction at the end. As noted in the introduction, the title is perhaps the catchline that appears in the large Nineveh MS of the ‘Hymn to Šamaš’ (K.3182+, MS NinNA1 in Rozzi Reference Rozzi2021): [o o o o o o a]n -e u ki-t[ì o o].

-

15. The restoration at the beginning is inspired by ‘Maqlû’ I 138 and 192 ((girra) nūr ilī kayyānu). If correctly restored, kayyān could be a nominalized adjective acting as the regens (as reflected in the translation), or else an adjective agreeing with nūru that interrupts the bound chain (**nūr ilī šamê u erṣeti kayyānu).

-

16. MS BabLB1 uses gír.tab for ád also in l. 92, so the suspicion arises that it may be a late convention rather than an error.

-

18. The restoration is inspired by ‘Marduk 1’ 10//12 (Fadhil/Jiménez Reference Fadhil and Jiménez2019: 167): ṭāb nasḫurka, “your attention is sweet.”

-

20. The confusion of lamassu and lamaš(t)u (BabLB1) also occurs in a late manuscript of ‘Marduk 1’ l. 176: lū atrat la-maš-šá-áš-šú (other MSS: la-mas-sa-šú, d lamma-šú) el [ i ša qadmi], “May his good fortune surpass that of before!” This orthography, together with the ušātu of l. 24 and šimat in l. 86 in BabLB1, may perhaps reflect a shift in the phonetic status of the sibilants in the terminal phases of Akkadian.Footnote 43

-

23–24. The phrase bēl usāti is particularly common in Akkadian onomastics (Stamm Reference Stamm1939: 212). Outside of proper names, the phrase is attested only rarely, e.g. in the ‘Dialogue of Pessimism’ 78 (Fadhil Reference Fadhil2022): ayyu bēl lemuttim-ma ayyu bēl usāti, “Which was the doer of evil, and which was the doer of good deeds?” As already noted by Montgomery (Reference Montgomery1908), the phrase also appears in Aramaic incantation bowls, as mry ʾswʾtʾ.

-

26ff. The addressee of the speech is probably Marduk. bēl mātāti (l. 28) is, of course, a traditional epithet of Enlil, but one that the god cedes to Marduk in ‘Enūma eliš’ VII 156. The restoration in l. 27 is inspired by the šuʾila ‘Marduk 1’ (Si.7+ // K.3505.B // K.17421+) l. 8: bēl(en) mātāti (kur.kur) šar (lugal) šamê (an-e) u erṣeti(ki -tì).

-

37. Words such as dannatu are usually not written logographically in library manuscripts of literary texts, so the decipherment may be incorrect.

-

38. The restoration at the beginning is based on ‘Ludlul’ V 82 (Hätinen Reference Hätinen2022): [ap]âtu mala bašâ marduk dullā, “[Tee]ming humankind, as many as they be, give praise to Marduk!”

-

39. The line appears verbatim in ‘Marduk 2’ (l. a+14; Lambert Reference Lambert1960b: 65): tattanašši lā lēʾâm-ma tereʾʾi ulāl[a]. Since ‘Marduk 2’ contains several verbatim quotations of other texts,Footnote 44 the present text is probably the lender and not the borrower.

-

43. ‘Ludlul’ V 56 (Hätinen Reference Hätinen2022): ušamḫir erba ṭaʾta igisê etandūti, “An offering, a gift, sundry donations I presented.”

-

46. ⸢gíl ! -la !⸣-tu 4 is a virtual emendation of the traces in MS SipNB1.

-

48. Compare the incantation in AO.17656 o 4 (Nougayrol Reference Nougayrol1947: 31): an-ḫu dal-pu šu-nu-ḫu a-me-lu.

-

49. Compare in the acrostic DT.83 r 3′ (eBL edition): ⸢zi⸣-⸢kir⸣ ša[p*-ti-šú] ⸢ki⸣-ma làl-la-ri ugu ab-ra-a-ti li-šá-ṭib, “May he make his speech as pleasant as honey to humankind.” gabbu is normally not a literary word; in particular its use as a noun is very rare in literature (see AHw. 272a s.v. gabbu I 1).

-

51. Compare the line ‘Ninurta as Savior’ 52 (Mitto Reference Mitto2022b), a line that has in the various manuscripts, all of them school tablets, a slightly different shape: manīt mīšari iddekkâššum-ma (var. tašâhšum-ma, var. tadekkâššum-ma) ša īṣa (var. ina īṣi, var. šattu) uḫalliqu irâbšu (var. urābšu) māda ?(lal), “That he will (var. ‘you will raise’ and ‘you will blow’) have a propitious breeze spring up for him and compensate him amply for every bit he had lost (var.: ‘for what he lost in a year’).” The difficulty of interpreting the line, particularly its last word, contrasts with the clarity of the opposition šattu : ūmakkal in the present hymn, and suggests considering our text as the lender and the Ninurta hymn (a Middle Babylonian composition, see Mitto Reference Mitto2022c) as the borrower.

The spacing in BabNBSch2 and in SipNB1 suggests that at least one word intervenes between ṭābu and tašâ]ḫšum-ma (?). MS BabNBSch2 could conceivably be emended to read ta-ziq ! -qa !, and šāru ṭābu then taken as a predicative complement instead of a direct object, but this solution is far from satisfactory. The sign after the second ta in BabNBSch2 could be š[aḫ.

-

52. Compare in the Hymn to Borsippa BM.61625+ ii 30 (eBL transliteration): [o] x x x x (x) ⸢ana ?⸣ is-qí-šú-nu ú-x [o o (o)].

-

53. ipru is, like gabbu in l. 49, a word of poor literary pedigree.

-

54. ⸢ki⸣-i-ni looks less likely.

-

59. Compare perhaps l. 114: šad(u) kīni (and commentary ad loc.).

-

64. Compare in the ‘Syncretistic Hymn to Gula’ A+54: tâmta ušraqqam ina nagbi mīlī ugappa[š], “The ocean she empties, in the deep she makes the floods huge” (Bennett Reference Bennett2023).

-

66. The verb at the end appears to be šakānu D, which is very poorly attested.

-

68. tu-šar-si is best interpreted as a hitherto unattested Š stem of the verb recorded in the dictionaries as russû (AHw. 996a: “etwa ‚(durch Wasser) aufweichen‘”; CAD R 425b: “to sully”). The meaning of the Š stem is perhaps similar to its D. As argued by Schwemer (Reference Schwemer2007: 9f.; Abusch/Schwemer Reference Abusch and Schwemer2011: 385), “to bind” (a meaning that its frequent parallelism with šuknušu seems to allow) appears to be the most common meaning of russû, since it translates Sumerian lá in bilingual texts and appears together with verbs such as kamû and kasû in magic texts. On the merism “the hill and the flatlands” (i.e., “everywhere”), compare e.g. ‘Erra’ IV 87: mūlâ u mušpāla kī aḫāmiš tagmur, “You have destroyed the hill and the flatlands alike.”

-

70. “Your plants” and “your wood” probably refer to that which Marduk is said to supply in the preceding lines. šuḫnu, “warmth,” is here attested for the first time outside of the lexical corpus.

-

71. In spite of the writing -ra-a of all Sippar MSS, berû must be the subject of šebû (an intransitive verb), like kaṣû in the following line.

-

72. On the use of a morphological Gtn stem (lištaḫḫan) with the meaning of the Gt stem in the preterite and precative of certain verbs, see Mayer (Reference Mayer1993: 337 ad 112; Reference Mayer1994: 115) and Streck (Reference Streck2003: 10–13).

-

73. mitḫāriš seems to govern balāṭi, as in ‘Theodicy’ 18 (nišī mitḫāriš apât[i], “the people, all mortals”) and 258 (lipit qāt aruru mitḫāriš napišti, “all living creatures, the handiwork of the birth-goddess”). The line in SipNB2 begins with a kúr, a particle that sometimes marks textual problems.

-

75f. As described in the introduction, these lines mention the Babylonian ‘three elements’: water, fire, and air.

-

81. ḫitmuṭū appears to be stative Gt, a rare stem known mainly in the adverb ḫitmuṭiš: according to Kouwenberg Reference Kouwenberg2010: 372f., ḫamāṭu Gt it is simply a literary use and has the same meaning of G and no detransitive value. It is possible that BabLB1, emended here, has a different verb (perhaps itmudu < itʾudu, naʾādu Gt). The use of the form bbl for wbl is very rare: see GAG §103j, AHw. 92a, and CAD A/1 10b). An erased decimal marker appears at the beginning of SipNB1.

-

82–85. Note the use of -bi for the plural -bū in MSS SipNB1 and BabLB1, perhaps resulting from contamination of nominal and verbal endings. See Mayer (Reference Mayer1992: 38 fn. 18) for a collection of NB and LB texts in which -i is used instead of the expected -ū/ā.

-

86. ba-nu-ú is best interpreted as a preposed adjective (banû I, “well-formed”), since it cannot be a participle (the expected form would be **bānû bītīšu)Footnote 45 or a stative (**bani). banû I, however, is apparently only here predicated of a building: it is normally used for people, words, or animals. Moreover, in the hymn several of the transitions between the sections have references to the “creation”: see in particular l. 100 and 127 (ibbanû). It seems possible, therefore, to interpret the adjective as deriving from banû A = IV, “to build.” Perhaps both senses of the word are intended at the same time, as reflected in the translation. Compare the etymology of the name of Esagil as bītu bānû napḫar il[ī], “the house that built all the gods,” as [sa7 = ban]û, kìl = napḫaru, and ìl = ilu (VAT.17115 ll. 7f. = George Reference George1992: 80 no. 5).

-

87. Since a reading pi-ta-at seems to yield no sense, it is assumed that the word written in the two Sippar manuscripts as wa -ta-at is the word booked in the dictionaries as itûtu A (CAD I/J 317a), itûtu I (AHw. 407b) and utā/âtu (AHw. 1443b). As noted in Jiménez Reference Jiménez2016: 223, the MSS of ‘Bullussa-rabi’s Gula Hymn’ 93 (itût kūn libbi ellil) attest to the readings ⸢e-ta⸣-[at], i-tu-ut (MSS Ashm-1937.620 and BM.62744) and e-ta-at (Sm.1036, see Földi Reference Földi2021a), so the word is attested as (w)e/itī/ū/ātu (the variant with u- is an Assyrianism).Footnote 46 At the end, compare ág = narām in VAT.17115 ll. 3f. (George Reference George1992: 80 no. 5).

-

88. The description of Esagil as a “replica of Apsû” and “counterpart of Ešarra” (the cosmic abodes of Ea and Enlil, respectively) is also encountered in ‘Enūma eliš’ V 120 and VI 62 (see George Reference George1992: 296f.). Compare also the similar line in an inscription of Esarhaddon: é-sag-gíl é.gal dingir meš | ma-aṭ-lat abzu ⸢tam⸣-šil | é-šár-ra mé-⸢eḫ-ret⸣ | šu-bat d é-a ⸢tam-šil⸣ | mul aš.iku, “Esagil, the palace of the gods, an image of the Apsû, a replica of Ešarra, a likeness of the abode of the god Ea, a replica of Pegasus” (RINAP 4 Esarhaddon 104 iii 47–51).

The line in MS BabLB1 is cited in CAD T 149a: according to it (ibid. 148a), this would be the only instance of a morphologically feminine plural form of tamšīlu. maṭṭalātu appears to be always a plural:Footnote 47 perhaps tamšīlu is built here analogically, or perhaps it is contaminated by tašīltu, “joy,” a word normally used in the plural.Footnote 48

-

89. It seems likely that the logogram gaba.ri, which normally stands for gab(a)rû or meḫru, but also for māḫiru and maḫāru (see Mayer apud Deller/Mayer Reference Deller and Mayer1984: 108) should stand in this line for meḫertu, “copy,” which is the word normally used as regens of temple names, most relevantly in ‘Enūma eliš’ V 120: mé-eḫ-ret é-šár-ra. In ‘Tintir’ IV 2 (George Reference George1992: 58f. 296f.), Etemenanki is the meḫret ešarra. There is no space at the end for a possessive suffix, so “the splendor of its aura” does not seem possible. The second half of the line is therefore perhaps best interpreted as an accusative of respect qualifying the first half, “an equal to Ešarra with respect to splendor an aura.” –mat in the three MSS that write šá-lum-mat should probably be interpreted as -mata.

-

92. Note the spelling šu-un-š[ú] in MS BabLB1: on the shift -mš- > -nš-, see GAG §31f.

-

93. Esagil is probably synecdochically called Eridu, as that is the name of the quarter in which it was located. According to ‘Tintir’ IV 3 (George Reference George1992: 58f. 300–303), Ekarzagina, the sanctuary of Ea in Esagil complex, is the “Gate of Apsû” (bāb apsî; abul arallî in l. 94 seems to be a synonymous phrase). bīt pirišti is normally understood as the “sacristy,” i.e. a room to store the garments of priests and statues of gods (so Doty Reference Doty1993); if taken literally, the phrase may refer to Ekarzagina in relation to Esagil, or else to Esagil in relation to the Apsû. Alternatively, it may be another etymology of the name of Esagil, based on the common equation sag/zag = pirištu.

-

94. markas šamê rabûti is another etymology of the name of Esagil in VAT.17115 l. 25 (George Reference George1992: 80 no. 5): [sa = marka]su, an = šamû, gíl = rabû.

-

95. The line, whose meaning is less than satisfactory, probably contains an etymology of the name of Esagil. Note (á-)áⓖ = têrtu, ìl = ilu, sa = milku (as in VAT.17115 l. 18 = George Reference George1992: 80 no. 5).

-

97. The line is probably an etymology of the name of Esagil, note: zag (i.e. sag) = eširtu, zag = tāmītu, an (from (pa.)an) = pelludû, an = išpikku (attested in the commentary on ‘Enūma eliš VII 65, see Heinrich Reference Heinrich2021; the origin of the equation is unknown), and sag/zag = pirištu (as in l. 93).The upper Winkelhaken of ta in MS SipNB1 (the only MS to preserve the word) is very weak, so one could conceivably read uš-ziz(zu), “sanctuary that established the rites.”

-

98. The couplet 97f. is “unbalanced,” i.e. its two halves are not grammatically independent (Jiménez Reference Jiménez2017: 74). The three units uṣrāti, šīmāti, and kullat nēmeqi niṣirt[i] appear to be appositive nouns to pirišti.

-

100. Compare ‘Tintir’ I 10 (George Reference George1992: 38): uru me-bi kal-laki = kimin (scil. bābilu) ālu ša parṣūšu šūqurū.

-

103. On the restoration at the end, see the note on the next line. ⸢d⸣+e[n] is of course also possible, but there seems to be space for one more sign.

-

104. urukugû, “pure city” is a byname of Babylon according to ‘Tintir’ I 49 (George Reference George1992: 40f. 266), where it is explained as ālu ellu in the Akkadian column. The phonetic complement -ú in the present text suggests normalizing it not as ālu ellu, as ‘Tintir’ does, but as urukugû. Note that Nebuchadnezzar’s bilingual ‘Seed of Kingship’ (Frame Reference Frame1995: 29 B.2.4.9 ll. 9–11) also seems to contain the Akkadianized version: uru kù–ga || uru.kù.ga. In l. 126, Urukugû is assigned to Enzag, the god restored here in l. 125; the restoration of Lugal-abzu, very uncertain epigraphically, is inspired by l. 125.

-

106. The phrase semer tamlî is known also in an inscription of Sargon II: ḫar meš tam-le-e tulīmānuš arkus-[ma], “I fastened inlaid bracelets on his two wrists” (e.g. in Frame Reference Frame2020: 364 ‘Sargon II 84’ v 58′).

-

107. The sequence is similar in inscriptions of Sargon II: na4 zú na4 za.gìn na4 babbar.dili na4 aš.gì.gì na4 ugu.aš.gì.gì (e.g. in Frame Reference Frame2020: 150 ‘Sargon II 7’ l. 142). Babylon is famously called “mountain of obsidian” (šadû ša ṣurri) in the Middle Babylonian ‘Games Text’ (HS.1893 o 1; Kilmer Reference Kilmer1991; Zomer Reference Zomer2019, no. 4); but since ṣurru appears as the first word of the line, it is unlikely that it should also be restored as the last one.

-

108. Jasper is called the “stone of kingship” also in the commentary BM.54312 l. 19 (George Reference George2006: 181), as well as in an inscription of Nabonidus (cited by George Reference George2006: 183f.).

-

110. It is possible to take inbī lalîša as a genitive chain, but MS SipNB1 places the caesura between the two words. Therefore, lalîša is taken as relational accusative.

-

111. The grammar of the line is difficult. The manuscripts seem to take kīma as a preposition, not a conjunction, since edê is a genitive; moreover, emūqā(tū)šu is in the nominative, and should therefore be the subject of (w)abālu (the masc. ending it-ta-nab-ba-lu in SipNB1, the only MS to preserve the verb, can be disregarded, since the use of -ū for the fem. pl. in verbs is much more frequent than would be the use of -u before suffix in emūqātū-šu for the acc./gen. plural). The object of the verb can therefore only be dumuqšu, of which kullu would then be an attributive adjective. The meaning would be, “like a wave, (Babylon’s) strength brings (Babylon’s) goodness attached,” i.e. its strength is the cause of its beauty. Alternatively, as suggested by an anonymous reviewer, one would take kul-lu as a stative kullā, “Like a wave, her strength brings her gooddness, provides (it).”

-

112. The line is cited in an Ashurbanipal hymn from found in Sippar (CBS.733+, eBL transliteration): mul d utu.è.a ù d utu.šú.a ṣa-⸢a⸣-[a-ḫ]u šam-šu <šu>-q[u-ru]. As seen by T. Mitto (privatim), the awkward phrase ṣayyāḫu šamšu is an etymological translation of the name of Marduk, where amar = zur = ṣâḫu and utu = šamšu. It is possible that šūquru (i.e. kal) is also part of the etymology, since another well-known etymology of Marduk, the “flood of a weapon” (abūb kakki, i.e. a-ma-ru tukul) also ends in -v l (on which see Lambert Reference Lambert2013: 165, who considers “doubtful whether the final l of tukul is amissable”).

-

113. The line may refer to the Šamaš Gate in Babylon. It would, however, be strange that only this gate should be mentioned; so, alternatively, it may refer to an archetypical gate in Babylon, whose size is such that they occupy “all that the sun (covers).” It is, however, strange that the gate should be mentioned before the wall makes its appearance (l. 114); so one may take the gate to refer instead to Marduk’s Star, Nēberu, mentioned in the previous line, whose “gate” would be located “where the sun (is).” Two manuscripts read an -e in the oblique case, although the sentence appears to be nominal. Other cases of writing an -e for the nominative are known in NB manuscripts, e.g. an-e ù ki -tì irūbū, “heaven and earth shake,” in all MSS of ‘Eriš šummi’ 31 (Fadhil/Jiménez Reference Fadhil and Jiménez2022: 235).

-

114. šad(u) kīni appears to be an etymology of the Imgur-Enlil, where Imgur < magāru = gin, and Enlil = šadû. Note the excerpt VAT.13234 (Bab.36574; Bartelmus Reference Bartelmus2016: 310):

⸢bàd⸣-bi im-gur-d+en-líl-le m[u-pà]-⸢da?⸣-bi d+en-líl še-še-ga

du-ur-šu im-gur-d+⸢en-líl⸣ ana zi-[kir ? šu ?-mi ?]-⸢šu ?⸣ im-[t]a-na-⸢x x⸣ d+en-líl

lú tìl-la šà-⸢ga⸣-a-né ⸢ki-tuš⸣ x x mi-[ni]-in-tuš-a

⸢a ? x (x) x x x x⸣ ma ? ⸢x⸣ [(x)] ⸢x (x) x (x) x⸣ ab [x (x)]

lú kar?-ra sa6-sa6-ga-bi? dumu? dnu-dím-⸢mud⸣

⸢x (x) mi x x x (x) x⸣ ma-⸢a ?-ar ?⸣ [d]nu-di-mud

-

115. On the appearance of Alulu, see “§1 Contents and Exegesis.” The epithet he receives, abi nišī aḫrâti, is etymological, since a = abu and (a-za-)lu-lu = nišū.

-

116. šikittu denotes here, as it normally does, “das Ergebnis des ‘Setzens’, nicht die Tätigkeit selbst” (Mayer Reference Mayer2017: 224). In other Akkadian texts it is Marduk who establishes Tigris and Euphrates, although the adscription to Ea is of course not surprising. On the mythological origins of Tigris and Euphrates, see in general Blaschke Reference Blaschke2018: 227–231.

-

117. Note in MS BabLB2 the use of the sign mak (ka×éš), on which see Frazer Reference Frazer2020. bamāti was interpreted by Landsberger “wie ṣuṣû normaliter Weideland” (Landsberger Reference Landsberger1949: 277 fn. 91), and specifically as the terrain between the river bed and the plateau, i.e. the river terraces (so also Leemans Reference Leemans1991: 119f.).

-

118. tâmati is interpreted as a singular form with anaptytic vowel because of the parallelism with ayabi (on forms of the napšatu type, see Jiménez Reference Jiménez2017: 77f., with further literature). The writing ⸢ta⸣-a-⸢tu 4⸣ of MS BabLB3, if not simply a mistake, could reflect the syncopation resulting from tâmatu > tâwati > tâati > tâti

-

119. The poetic tone of the text does not seem to allow an interpretation of the verb as parû, “to vomit,” so it seems advisable to take the verb iptanarrâ (in the NB MSS) or iptarrâ (LB, “gnomic” preterite) as related to the verbs booked in the dictionaries as parāʾu II (“to sprout”; AHw. 833, CAD P 182, EDA P0382: u/u) and parāḫu I (“to ferment”; AHw. 827, CAD P 145, EDA P0403: a/?), which are usually understood as lexical variants of each other (e.g. Stol Reference Stol2008: 351; EDA P0403). dīša u šamma would then be relational accusatives. Since both verbs have complementary distributions (parāḫu I is only attested lexically and in OB; parāʾu II only in NA), and since parû “to vomit” (u/u), attested almost exclusively in medical texts, has no convincing etymology (EDA P0379),Footnote 49 one could perhaps understand that the three forms are variants of the same verb, whose etymological meaning (“to sprout”) would have acquired a more specific meaning (“to vomit”) in medical texts, perhaps by lexical transfer (compare German spritzen vs. sprießen) or euphemism.

-

120. Lit. “Having its meadows been made resplendent, barley sprouts.” The reading adopted in the reconstructed text, šunmurā, is preserved only in MS SipNB1 (the sign in question resembles šu rather than ku, and the -n- supports the reading šunmurā over kunmurā, as šunmurā is the regular morphographemic writing of šummurā, whereas kunmurā would involve an unusual dissimilation from kummurā).

-

121. The strange variant of the two LB MSS, kurunnu, written kurun.nam, is probably a corruption of gurrunu, although one that makes sense in the context. Note that writing gu-ru-nu in MS SipNB1 could be interpreted as q/gurunnu, “heap,” a noun phonetically closer to kurunnu and which would then be in apposition to karê (the latter in bound form, < karā- < Sum. kara6, see Attinger Reference Attinger2021: 657). MS BabNB2, however, does not admit this interpretation.

-

122. gipāru appears to be used here metonymically not for the “pastureland” (on this meaning of gipāru, see Held Reference Held1976: 232 fn. 14), but for the “cattle”; gipāru u laḫru would then be a poetic equivalent of the more prosaic lâtu((áb.)gu4 ḫi-a) u ṣēnū(u8.udu ḫi-a), “herds and flocks.” aburriš rabāṣu expresses “not primarily the idea of safety, but rather stresses exuberance and delight. Water-meadows, recently emerged from the river, will soon have been covered by young grass (…) which together with the immediate vicinity of water for drinking and bathing made (…) an ideal pasture for cattle, a proverbial pleasure resort” (Veenhof Reference Veenhof1973: 374).

-

123. The phrase simat baʾūlāti is apparently only attested at the beginning of ‘Poor Man of Nippur’ (l. 5, Heinrich Reference Heinrich2022a), probably an allusion to our text: ul īši kaspa simat nišīšu | ḫurāṣa ul īšâ simat baʾūlāti, “He had no silver, as befits his people, | He had no gold, as befits humankind.”

-

124. ab-⸢ḫu⸣ fits the traces in SipNB1 better than ab-⸢ri⸣ (< apāru?). Several parsings of the signs ab–⸢ḫu⸣ seem possible, none of them without difficulties: (1) an irregular form of ebēḫu, “to girt” (for other examples of phonemic a written as e in NB texts, see Woodington Reference Woodington1982: 20); (2) a form of the rare verb (w)abāʾu, “to be full of weeds, to grow wild” (CAD U/W 397b; but cf. AHw. 1454: “verunkrauten”), hitherto poorly attested in first-millennium texts, and otherwise written with w- and aleph; (3) a form of the verb abāḫu (AHw. 56a. 1544a: “behaftet sind”), which is apparently otherwise known only from a passage in an acrostic hymn to Nabû (K.8204): šá šul-ḫa-a u mi-iq-ti ab -ḫu ú-qa-a-ú ka-a-[šá], “he who is ab -ḫu by … and sickness expects you.” This last line is understood by AHw. 56a as “die mit … behaftet sind (?)”; CAD N/1 270a and Š/3 240a read èz-ḫu, from ezēḫu, “to gird on” (a verb of which no other metaphorical use appears to be known). It seems more likely that both the acrostic hymn to Nabû and the present text should be read as ès-ḫu (< esēḫu, “to assign”), despite the fact that the reading ès of ab is relatively rare.

-

125. ummatu means “descendant” (Finkel Reference Finkel1988: 149 fn. 57) or “(Angehöriger einer) Gruppe von Kultpersonal” (Jursa 2001/Reference Jursa2002: 84a) in some contexts. Since both ummatu and nišūtu are feminines, tukkulu is interpreted as an epithet of Lugal-abzu (i.e. Ea, Krebernik Reference Krebernik1987/1990a). Ninazu is usually identified with Ninurta, more rarely with Nergal (Wiggermann 1997: 33–35; Reference Wiggermann1998/2000: 333a).

-

126. On urukugû, see the comment on l. 104. uru.kù.ga-ú may also be taken as a substantivized nisbe form, “Urukageans,” i.e. “Babylonians.” Lugal-asal is usually identified with Nergal (Krebernik Reference Krebernik1987/1990b), which in the context makes little sense. A diverging tradition makes Lugal-asal the father of Zarpanitu, i.e., Marduk’s father-in-law. Thus, a hymn to Zarpanitu reconstructed by T. Mitto:

mu-de-e [… šamê(an-e)] ⸢u⸣ erṣeti(ki)-tì mi-lik dur-an-k[i]

ši-i-ma ⸢i⸣-[lat] i-lá-a-ti mārat(dumu.munus) šar (lugal) ilī(dingir meš) d lugal-giš ása[l]

ši-i-ma [be-l]et be-le-e-ti kal-lat bēl(en) ilī(dingir meš) d lugal-abzu

[š]i-⸢i-ma⸣ šar-rat šar-ra-a-ti ḫi-rat šar (lugal) ilī(dingir meš) d asar-lú-ḫi

d iš-tar d iš-tar meš ši-i-ma um-mi e-tel ilī(dingir meš) d en-zag

Well versed in [… of heaven] and earth, the advice of Duranki, Cf. 126

She is goddess among goddesses, daughter of the king of the gods, Lugal-asal, Cf. 126

She is lady among ladies, daughter-in-law of the lord of the gods, Lugal-abzu, Cf. 104. 125

She is queen among queens, wife of the king of the gods, Asalluḫi,

Ištar among Ištars, she is the mother of the foremost of the gods, Enzag. Cf. 103. 126

K.3031 o 11′–r 1 // Sm.1719 r 1–4 // BM.31749 r 1–2 // BM.35923 r 1–5 // BM.38468+ r 1–5

Enzag is a god of Dilmun, identified with Nabû in Mesopotamia (Pomponio Reference Pomponio1978: 175–176; Nashef Reference Nashef1984: 8–10).

-

127. The line refers to the antediluvian king Alalgar i.e. to the second ruler of Eridu after kingship came down from heaven according to the ‘Sumerian King List’. The name of the king is written as e||á||a-làl-gar in the ‘Sumerian King List’ (s. Jacobsen Reference Jacobsen1939: 70; and George Reference George2011: 199 no. 96 o 3. 201 no. 97 o 3. 202 no. 98 i 5), as m a-lá-al-gar in the ‘Uruk List of Sages and Scholars’ (IM.65056 o 2 = W.20030/7, BagM Beih. 2, 89) and as ᾽Αλάπαρος by Berossus (De Breucker Reference De Breucker2012: 232).

-

128. aburrūtu is a hapax legomenon. The word is probably related to abrātu, a poetic designation for “people.”Footnote 50 The Assyrian word (a)gu(r)ru/atu, “ewe,” is probably irrelevant here.

-

130. Note the strange ending -ḫa in MSS SipNB1 and BabNBSch3 for what should be the masculine plural -ū. An emendation to a fem. pl. -ḫa-<tú> in both MSS seems unlikely.

-

132. As interpreted here, šarru ana šarri is a distributive expression, like šattu ana šatti and arḫu ana arḫi (see the references to such expressions collected by Mayer Reference Mayer1989: 163 fn. 20). One may also consider restoring ana lugal dingir m[eš šu-ba-a]r-šú-nu, although the spelling šubaršunu instead of the regular šubarrâšunu (< Sum. šu-bar-ra) would be surprising.Footnote 51 ana could also be interpreted as “in favor of,” i.e. the king establishes their freedom so that they can devote themselves to the service of the king (of the gods).

-

133. ramkūtu is just as common as ramkū as the plural of ramku (CAD R 127a: see also Still Reference Still2019: 194 with cases in which ramku designates a “priest” in general, not a specific caterogy). Alternatively, one may restore [… uru ak]-ka-di and assume that Akkad is here a poetic byname of Sippar, just like Eridu is of Babylon.Footnote 52 No other occurrence of ebbu as a type of priest is known,Footnote 53 so the term may just be an adjective: “pure ones.” The priests of Ištaran are presumably from Der, those of Šamaš probably from Sippar.

-

134. The word b/puḫl(a)lû was previously attested only in an inscription of Assurbanipal: adi sangugê/šangê bu-uḫ-la-le-e ašlula ana māt aššur, “(the Elamite gods) along with the šangû Footnote 54 and buḫlalû-priests I took captive to Assyria” (RINAP Ashurbanipal 9 v 33. 11 vi 46. 96 r i′ 2′). Vallat (Reference Vallat2001) suggested that the word is a composite of puḫu, “child,” and lar/lal, “priest,” so the meaning would be “seminarist.” Elamites resident in Babylonia during the Middle Babylonian period were generally of lower classes (Zadok Reference Zadok1987: 15; Sassmannshausen Reference Sassmannshausen2001: 133), but those mentioned in the text are priests of Šušinak (or: of Susa). Parallelism with buḫlû would suggest taking nibru ki-ú not as the gentilic (“Nippurean”) but rather as a designation of a group of priests (“priests of Enlil”?). The same usage may perhaps be attested in a late copy of an inscription of Kurigalzu II (MS 3210; George Reference George2011, no. 61 // George Reference George2012), according to which certain “Nippureans” (dumu meš nibru ki) were massacred in the courtyard of the temple Esaⓖdiⓖirene, the only known temple of such name being in Dūr-Kurigalzu; one of the possible explanations is that these were Nippureans living in Dūr-Kurigalzu (so Clayden Reference Clayden2017: 448 fn. 39); the place where they were massacred suggests perhaps that they were priests (so Bartelmus Reference Bartelmus2017: 254).

-

135. The verb uš-ba-áš-šú is interpreted as ušbaššū, i.e. as bâšu Š. Only a doubtful occurrence of the Š stem of bâšu is booked in the dictionaries (AHw. 1547b), in an Old Babylonian letter: matīma anāku ana bīt rāmānīya uš-bi-iš, “Have I ever made him ashamed of my own house?” in (Ashm-1923.342 = OECT 3, 74 = AbB 4, 152 l. 19).

-

136. Cf. BM.65653 vi 19′ (eBL transliteration, Hymn to Borsippa): šá a-bi-ri-i ḫa-áš-šú ḫa-at-nu la ma-gi-ri i-du-uš-šú ri-x [(o)]. ḫaššâ is probably the same word written as ḫa-aš-ša-a-ú in OB Lu A (MSL 12, 160):

The word appears probably also in the ‘Hymn to Ninurta as Savior’ 38: ḫaš-⸢šá-mu⸣-ú ana emūqīšu u anāku akû adallal kâšu, “the weak one for his strength, and I, the helpless, praise you!”Footnote 55 The existence of the word ābirû, of uncertain etymology and not booked in the dictionaries, was first detected by Lambert (Reference Lambert1982: 282–283).

-

138. mār mīti for “orphan” or “heir” is attested only in Old Assyrian sources and in Nuzi (CAD M/2 140b), and literary manuscripts generally restrict the use of logograms to the most common words only; but no other parsing of dumu úš seems convincing.

-

139. As interpreted here, the Babylonians’ generosity to their captives is such that they would be willing to pay a talent of silver, an exhorbitant amount, to set them free.

-

140. AššNASch1 áš-pi has been read as [ša] našpi, “they (the people of Babylon) distribute rations of našpu-beer” (CAD Z 144a) and [šá k]a ?-áš-pi, “von (ihrem eigenen) Silber stellen sie einen Anteil bereit” (Maul/Manasterska Reference Maul and Manasterska2023: 112). In view of MS SipNB1, it should probably be read as lā (w)ašbu: (Neo-Assyrian texts occassionally write /p/ with b-signs and vice versa; see GAG3 §27d*; Deller Reference Deller1959: 234–242 §47; Parpola Reference Parpola1983: 255 fn. 457; Luukko Reference Luukko2004: 72f.; De Ridder Reference De Ridder2018: 127–130). When the Babylonians divide an inheritance with someone who is absent, they perform a pious act toward someone who would not have noticed their lack of piety. In doing so, they defy the cynical wisdom of the proverb BM.38297+ ii 8–10 (partially Lambert Reference Lambert1960a: 268): lú al-ti-la áš;-a-na-ne (x) aš-ak-ab [l]ú nu ti-la «ab» [e]me-sig-šè dug4-ga-ab | ša áš-bi e-pu-uš ṣi-bu-ti ša la áš-[bi] a-⸢kul⸣ ⸢kar*⸣-[ṣi-šú], “of the present, fulfill his desires; of the absent, say slander.” The term lā ašbu may have a more concrete meaning in the context, perhaps similar to Old Assyrian laššuʾu, “absent,” i.e. living in Aššur and not in the colony, as opposed to wašbu, “present” (Dercksen Reference Dercksen2004: 127–130).

-

141. The signs ik-⸢ke-e⸣ are relatively clear on the tablet. CAD K 351b parses the word as ki-i-ik-ke-e palḫi<š>, connecting it with the adverb kīkî, “how?” A rhetorical question or exclamation seems out of place in the context. Mayer Reference Mayer2009: 439 normalizes the word as kī ikkē palḫi and translates it as “in ehrfurchtig-gestimmter Weise.” This seems the best interpretation in view of the similar expressions kī ikkim “in launischer Weise, aus Laune,” and specially kī ikki rīqi ū kimilti, “in leichtfertiger Laune oder im Zorn” (Mayer Reference Mayer2009: 431, on the latter cf. also Paulus Reference Paulus2014: 438), albeit the additional -e seems difficult to justify.

-

144. MS SipNB1 could also be read -qú !, but the writing would be very strange; moreover, as reflected in AššNASch1, the line “is hardly correct as it stands” (Landsberger/Jacobsen Reference Landsberger and Jacobsen1955: 21 fn. 26). emūqāt, “the hosts,” enables a more satisfactory understanding of the line. As interpreted here, mišaru is a variant of išaru Footnote 56 (an interpretation as mīšari, “Ningirsu of righteousness,” i.e. “righteous Ningirsu,” is of course also possible, although poetry tends to avoid complex genitive chains). The variant mešrâ for mīšaru is attested also in two parallel lines of the šuʾila prayer ‘Ištar 1’, the first of which has imnuk mi-šá-ri, the second šá imnukki mešrâ (see also Mayer Reference Mayer1992: 40 fn. 22; Zgoll Reference Zgoll2003: 194. 196 ll. 17. 32). The variant is reminiscent of the writing of the word mīšaru as meš-šá-r v, which is attested occasionally (Jiménez Reference Jiménez2022: 64 ad 39) and may have originated as an erroneous parsing of it.

-

149. Since ugbabātu-priestesses were famously celibate –in ‘Atramḫasīs’ III they are among the professions established to to keep the population’s birth rate under control– the “partners” (ḫāmerū) mentioned in this line are in all likelihood their divine or spiritual spouses, i.e. the gods to which they are devoted (so also Stol Reference Stol2000b: 461f.).

-

150. The line seems to imply that the nadītu plays a role as a midwife (see already Harris Reference Harris and Biggs1964: 135; Lambert Reference Lambert and Haas1992: 144; Stol Reference Stol2000a: 172f.). The “midwife” (šabsūtu) is elsewhere associated with the qadištu (von Soden Reference von Soden1957: 119f.; Stol Reference Stol2000a: 173).

-

151. qašdātu are normally associated with wet-nursing: see Lambert Reference Lambert and Haas1992: 144f.; Stol Reference Stol2000a: 186–188. The word šuḫtu is a hapax legomenon, it is a purs-form of šaḫātu IV, “to wash.”

-

152–155. These lines could refer to the women of Babylon alone, or to all Babylonians (the ending -ā in the verbs would then refer to “the people,” nišū).

-

153. The reading r[a-šá-a] follows Maul/Manasterska Reference Maul and Manasterska2023: 112; cf. Ebeling Reference Ebeling1925: 8: i ?-[na t]e-me-qí.

-

154. The word nakdu (on the reading with -k- instead of -q- see Stol Reference Stol2010: 43f.) is equated with palḫu in the commentary on ‘Theodicy’ l. 22 (Heinrich Reference Heinrich2022b): nak-di : pa[l-ḫu].

-

157. The restoration at the beginning is inspired by ‘Gilgameš’ MB Ug1 13 (George Reference George2022): šū rīmšina šina arḫātu, “(Gilgameš lets no young bride go free to her husband,) he is their (fem.) wild bull, they (fem.) are (his) cows,” see also ‘Gilgameš’ SB I 71). kul-lat bābili has been interpreted as “of all Babylon” (Foster 2005³: 878), “von ganz Babylon” (Ebeling 1925: 9; Reference Ebeling and Gressman1926: 216) and “von Babylon in seiner Gesamtheit” (Maul/Manasterska Reference Maul and Manasterska2023: 114). Although the expression seems solecystic (CAD K 505b gives no other example of kullat GN, but cf. tin.tir ki gab-bi e.g. in SAA 17, 21 r 3. 5), no better alternative suggests itself. Collation reveals that the sign after ⸢ká⸣.dingir.ra ki is su, not la, as read in previous editions. The word gained is sug/kullu, “herd.” The collation of the divine name at the end of the line allows the awkward reading found in earlier editions of the excerpt (an-da-ḫaṣ) to be dismissed, thereby eliminating the need to introduce a speaker into the context.

-

159. The readings adopted, t[a and i-⸢bat !⸣-[t]aq, look possible on the tablet, but not certain. In ḫu-ub-ba-t[a-šú-nu, one may either excise ba (ḫu-ub-«ba»-t[a-šú-nu, i.e. ḫubt[ašunu) or take it as an anaptyptic vowel, although the expected vowel would be /bu/ (see Parpola Reference Parpola1983: 47).

-

191–198. The verbs in this section seem to be preterites and statives, not precatives.

-

192. Compare the apodosis attested e.g. in ‘Šumma Ālu’ XXIII 20′ (Freedman Reference Freedman2006: 204; also 1881,0727.59 r 10; eBL transliteration): bēl bīti šuāti ḫengalla uštabarra, “the owner of that house will enjoy permanent prosperity.”

-

193. Cf. ‘Enūma eliš’ I 13 (Heinrich Reference Heinrich2021): urrikū ūmī uṣṣibū šanāti, “Lengthy were they of days, added years to years.”

-

205. The word nagalmušu, equated with gitmālu, “perfect”; šaqû, “lofty”; and nabû, “shining” in ‘Malku’ I 68f. and IV 178 (Hrůša Reference Hrůša2010: 201. 305. 389), is elsewhere attested only in a fragment of a Neo-Assyrian prayer (VAT.11666 = KAL 9, 15 o (?) 2′) and in an Old Babylonian text that mentions Narām-Sîn (BM.120003 l. 37, see Lambert Reference Lambert1973: 361. 363).

-

206. Compare ‘Eriš šummi’ 14 (Fadhil/Jiménez Reference Fadhil and Jiménez2022: 233): šarru ekdu ša rāšuššu agîš etpuru (var.: šitpuru) burummī ellūti, “Fierce king, who wears on his head the pure heavens like a tiara.”

-

209. Compare BM.76692 6′ (eBL transliteration): […] x x x ub-bat dūr(bàd) [abni (?) …].

Acknowledgements

Thanks are expressed to M. Frazer and an anonymous reviewer for the careful revision of the manuscript. The text was read at the Keilschriftwerkstatt of LMU Munich in 2023, and ideas provided by its participants are acknowledged in the commentary. The tablet in the Iraq Museum is published with the kind permission of the College of Arts (University of Baghdad) and the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage; those in the British Museum are presented here by permission of the Trustees of the British Museum. Thanks are expressed to J. Eule (Vorderasiatisches Museum) for facilitating the collation of MS AššNASch1, to J. Taylor for providing access to the British Museum’s collection of formerly unnumbered fragments (MS SipNB4) and to K. Simkó for some last-minute collations. The article was written under the auspices of a Gerda Henkel “Patrimonies” Project; the tablet from the Sippar Library was conserved in the framework of the project “Cuneiform Artefacts from Iraq in Context” (Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften).

Without the eBL platform (https://www.ebl.lmu.de/) and the work of the entire eBL team, it would be impossible for this edition to use 21 manuscripts, consisting of 31 fragments, most of them previously published only on eBL. A debt of gratitude is owed to the whole team, especially to those who have contributed digital (Zs. J. Földi, A. Hätinen, T. Mitto, J. Peterson, L. Sáenz, H. Stadhouders, J. Taniguchi) or manuscript (A. R. George, W. G. Lambert (†), W. R. Mayer) transliterations that served as the basis for the identification and edition of the manuscripts of this text.

The article is dedicated to the honoree of the ‘Approaches to Cuneiform Literature’ conference, in deep gratitude for his mentorship and support over the years.