Management Implications

Lonicera maackii (Amur honeysuckle) is an archetypal invasive shrub from East Asia. A better understanding of how to treat this species can provide insights into the control of other invasive shrubs species that, as a group, are a nearly ubiquitous threat to forests of the eastern United States. The herbicide glyphosate (often in the cut stump method of application) is commonly used in the treatment of L. maackii and other invasive shrubs. However, in recent years, interest has grown in using lower concentrations of glyphosate and other herbicides in control efforts due to landowner concerns about non-target effects.

Our study examined whether the addition of a novel adjuvant increased efficacy of glyphosate treatment in the cut stump method of control (defined by a basal horizontal cut and the application of herbicide). This novel adjuvant—2XL—is a commercially available cocktail of cellulases (enzymes that break down a key component of woody-plant cell walls) derived from fungi. Conceptually, 2XL would break down the cell walls of the vascular tissues, allowing glyphosate to diffuse more easily into the plant. This would, hopefully, allow effective control to be achieved with lower concentrations of glyphosate.

While 2XL was not an effective adjuvant, we found that concentrations less than half (30 to 60 g L−1) the widely recommended range (∼98 to 122 g L−1) of glyphosate were equally as effective at preventing posttreatment stump resprouting. This result suggests that lower concentrations of glyphosate may be effective in controlling L. maackii. Additional research is needed to determine whether lower concentrations of herbicide can be effective in controlling other invasive shrubs.

Introduction

Invasive species are causing the widespread degradation of numerous ecosystems and are threatening the survival of many native plant species (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Mitchell and Graham2002; Oswalt et al. Reference Oswalt, Fei, Guo, Iannone, Oswalt, Pijanowski and Potter2015; Richardson et al. Reference Richardson, Allsopp, D’Antonio, Milton and Rejmánek2000; Sakai et al. Reference Sakai, Allendorf, Holt, Lodge, Molofsky, With, Baughman, Cabin, Cohen, Ellstrad, McCauley, O’Neil, Parker, Thompson and Weller2001). The increased abundance and distribution of invasive species are closely tied to a decrease in global biodiversity and reduced ecosystem function (Butchart et al. Reference Butchart, Walpole, Collen, van Strien, Scharlemann, Almond, Baillie, Bomhard, Brown, Bruno, Carpenter, Carr, Chanson, Chenery and Csirke2010). The estimated costs of controlling invasive species and the ecological damage they cause may be as high as $120 billion annually and will likely continue to rise (Pimentel et al. Reference Pimentel, Zuniga and Morrison2005).

Woody species, specifically shrubs originating from East Asia, often possess traits that make them particularly well suited to invade eastern North American forests (Iannone et al. Reference Iannone, Oswalt, Liebhold, Guo, Potter, Nunez-Mir, Oswalt, Pijanowski and Fei2015, Reference Iannone, Potter, Guo, Liebhold, Oswalt, Pijanowski and Fei2016; Ricklefs et al. Reference Ricklefs, Guo and Qian2007). East Asian shrub species have an extended leaf phenology that results in a longer growing season than native plant species, allowing them to fix additional carbon and outcompete native species (Fridley Reference Fridley2012). Thus, East Asian shrubs are aggressive invaders of eastern North American forests, and controlling their establishment and spread across the region has become difficult and costly for land managers (Rathfon and Ruble Reference Rathfon and Ruble2007). Developing safer, more effective ways to control invasive shrubs is critical to the maintenance of biodiversity and ecosystem function (Webster et al. Reference Webster, Jenkins and Jose2006).

One particularly problematic invasive shrub is Amur honeysuckle [Lonicera maackii (Rupr.) Herder]. Its vigorous root growth, woody character, and prolific resprouting make this species particularly difficult to control (McNeish and McEwan Reference McNeish and McEwan2016). Lonicera maackii was introduced intentionally to the United States for the first time in 1897 (Luken and Thieret Reference Luken and Thieret1996). After several subsequent importations, it quickly spread across the eastern hardwood forests due to rapid maturation (Deering and Vankat Reference Deering and Vankat1999), high fecundity (Lieurance Reference Lieurance2004), and widely dispersed seeds (Gorchov et al. Reference Gorchov, Henry and Frank2014). Lonicera maackii is known to inhibit native species by limiting access to light, due to its dense canopy and extended leaf phenology (McNeish and McEwan Reference McNeish and McEwan2016). The leaves of L. maackii emerge earlier in the spring and are retained longer into the fall than leaves of most native plants, which negatively affects the establishment and growth of herbaceous and woody competitors (Schulte et al. Reference Schulte, Mottl and Palik2011). This species also has indirect effects on forest ecosystems through altered nutrient cycling (Schuster and Dukes Reference Schuster and Dukes2017), as well as the production of potentially allelopathic chemicals (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Shannon, Stoops and Reynolds2012).

A variety of treatment techniques are used to control invasions of L. maackii (as well as many other woody shrubs); all are included in at least one of the following four categories: physical, biological, cultural, and chemical (Radosevich et al. Reference Radosevich, Holt and Ghersa1997). Physical removal includes manual techniques such as root wrenching, lopping, or root severing (Oneto et al. Reference Oneto, Kyser and DiTomaso2010), as well as mechanical removal in the form of brush-cutting and mulching-head treatments (Frank et al. Reference Frank, Saunders and Jenkins2018). While these methods may disturb the substrate, they are generally considered to be more environmentally safe and can be relatively inexpensive to apply but may require more work hours than other treatments (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Saunders and Lowe2011), and some manual techniques require access to specialized equipment (Frank et al. Reference Frank, Saunders and Jenkins2018; Oneto et al. Reference Oneto, Kyser and DiTomaso2010). Fire is another widely used physical method for controlling some invasive woody plant species (Mandle et al. Reference Mandle, Bufford, Schmidt and Daehler2011). While efficient (Ward and Williams Reference Ward and Williams2011; Ward et al. Reference Ward, Williams and Worthley2013), this method is varyingly effective across shrub species and may promote the establishment of some invasive plants (Guthrie et al. Reference Guthrie, Crandall and Knight2016; Mandle et al. Reference Mandle, Bufford, Schmidt and Daehler2011; Rebbeck Reference Rebbeck2012; Ward and Williams Reference Ward and Williams2011; Ward et al. Reference Ward, Williams and Worthley2013). Biological control is the least common form of woody species control but is gaining acceptance as an alternative treatment (Rosa García et al. Reference Rosa García, Celaya, García and Osoro2012). For example, goat grazing has been examined as a means of biological control for invasive shrubs, and while concerns over specificity and access exist, this method shows potential for future use (Elias and Tischew Reference Elias and Tischew2016; Luginbuhl et al. Reference Luginbuhl, Harvey, Green, Poore and Mueller1999; Rathfon et al. Reference Rathfon, Greenler and Jenkins2021). Cultural techniques are also an important pillar of woody species control. Cultural techniques can include physical and biological removal techniques but are more associated with a place and a people. Examples of cultural control include farming techniques such as annual tilling (Radosevich et al. Reference Radosevich, Holt and Ghersa1997) and cultural burns (Hannibal Reference Hannibal2014). These techniques are immensely important; particularly in regard to indigenous peoples (Pierotti and Wildcat Reference Pierotti and Wildcat2000).

Herbicide application, often in combination with physical methods, is one of the most commonly used treatments for control of invasive woody shrubs (Webster et al. Reference Webster, Jenkins and Jose2006). Specific herbicide foliar treatments are quick, cost-effective, and efficient but can lead to non-target effects on some native species (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Saunders and Lowe2011; Howle et al. Reference Howle, Straka and Nespeca2010; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Clarke and Church2018). Individual plant treatments such as “hack and squirt,” girdling, basal bark applications, and stem injections are also commonly used for an array of species (Hartman and McCarthy Reference Hartman and McCarthy2004; Loh and Daehler Reference Loh and Daehler2008; Oneto et al. Reference Oneto, Kyser and DiTomaso2010; Rathfon and Ruble Reference Rathfon and Ruble2007). The cut stump method typically involves the use of clearing saws to cut a woody stem horizontally at its base, followed by an application of a systemic herbicide to the cambium of the exposed surface (Luken and Mattimiro Reference Luken and Mattimiro1991). This technique combines the specificity of manual removal with the efficiency of chemical treatment. The cut stump method is generally considered preferable for invasive shrub control because of its efficiency both economically and in treatment (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Saunders and Lowe2011) However, as with any management approach, because of the posttreatment resprouting and the ability of invasive shrub stumps and seeds to remaining viable in the soil for many years, follow-up treatments are typically required, which can be both costly and time-consuming (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Saunders and Lowe2011). Glyphosate is a widely used herbicide with the cut stump method, and its use is considered to be relatively low risk compared with many other herbicides (Baylis Reference Baylis2000; Tarazona et al. Reference Tarazona, Court-Marques, Tiramani, Reich, Pfeil, Istace and Crivellente2017). Yet there is still concern regarding glyphosate’s non-target effects (Busse et al. Reference Busse, Ratcliff, Shestak and Powers2001; Gill et al. Reference Gill, Sethi, Mohan, Datta and Girdhar2018), misapplication (Tsui and Chu Reference Tsui and Chu2003), and even possible carcinogenic effects, as suggested from hazard assessments conducted by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (2015). This combination of issues has resulted in landowner concerns regarding the use of glyphosate and other herbicides on their properties (Howle et al. Reference Howle, Straka and Nespeca2010; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Clarke and Church2018).

Finding ways to improve invasive plant control techniques and getting the public, specifically landowners, to understand the importance of controlling invasive species are critical to protecting native species. One approach to reduce concerns and increase treatment efficacy is to develop ways to effectively treat invasive species with lower concentrations of herbicides. The use of chemical adjuvants (a substance added with the intention of increasing the efficacy of the active ingredient) may provide an approach that maintains efficacy at a lower herbicide concentration. One potential adjuvant, 2XL, is a commercially available cocktail of cellulases that was originally derived from the fungus Aspergillus niger. While similar enzymes have been suggested for use in the degradation of woody plants for bioethanol production (Scharf and Boucias Reference Scharf and Boucias2010), cellulases may have a wide range of applications. Because these enzymes digest cellulose, which is a key structural component of the plant cell wall, we hypothesized that 2XL would increase herbicide efficacy in cut stump treatments of invasive shrubs through the possible degradation of plant cell walls. While little is known about glyphosate’s entry into the plant through the vascular tissue of a cut stump, examining the herbicide in combination with 2XL may help direct further research into elucidating this pathway.

To test whether the addition of 2XL on treated woody stumps would increase the efficacy of glyphosate, we conducted a field experiment using the cut stump method of treatment on a particularly problematic invasive shrub, L. maackii. In our experiment, we tested combinations of three concentrations of 2XL with five concentrations of glyphosate and predicted that lower concentrations of glyphosate combined with 2XL would be as effective in limiting the resprouting of L. maackii as higher concentrations of glyphosate without the enzyme product.

Materials and Methods

Study Sites

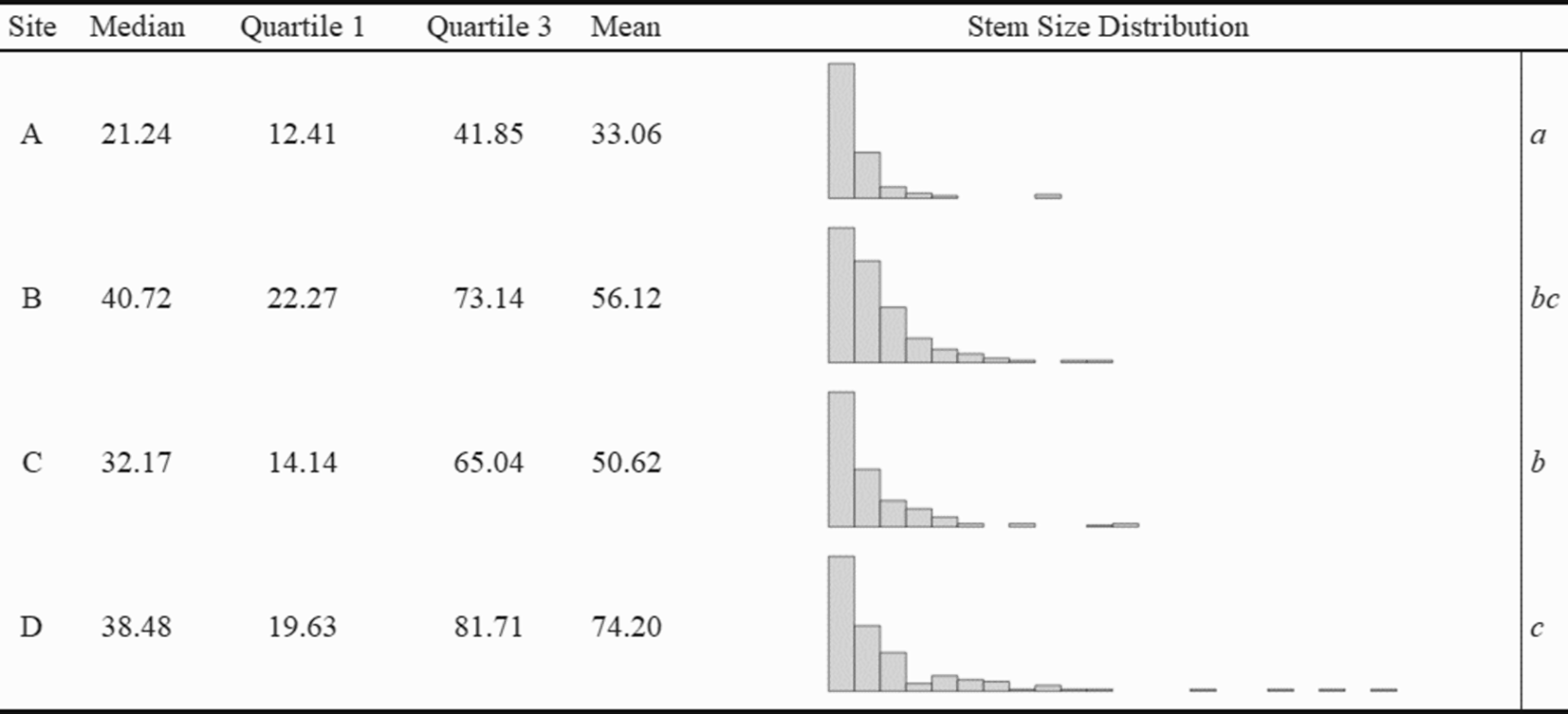

We established four replicate sites within mature, secondary, mixed-hardwood forests at the Richard G. Lugar Forestry Farm (henceforth referred to as “Lugar Farm”) in northwest Indiana (40.423827°N, 86.961725°W). Overstories were dominated by oak species (Quercus spp.), honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos L.), sugar maple (Acer saccharum Marshall), and black cherry (Prunus serotina Ehrh.). Forests at Lugar Farm are heavily invaded with dense thickets of L. maackii (Shields et al. Reference Shields, Jenkins, Saunders, Gibson, Zollner and Dunning2015), and the sites have received little or no treatment for any invasive plant species. Topographically, the sites were generally flat, with slopes of less than 5%. While the abundance of L. maackii stems was similar across sites, an ANOVA (F(3, 628) = 10.20, P < 0.001) and Tukey HSD test revealed that there were significant differences (P < 0.05) in the total basal area between replicates (Figure 1). The total basal area of individual shrubs was calculated as the summed basal area of all stems comprising the individual.

Figure 1. Median and quartiles of total site basal area (calculated for 150 individuals at each site) and distribution of individual Lonicera maackii basal area across study sites at the Richard G. Lugar Forestry Farm in northwest Indiana. Total basal diameter for each shrub was calculated by summing the basal area of each individual’s stem or stems, which were calculated from their basal diameters. All units are in square centimeters. Histogram X axis ranged from 3.1 cm2 to 656.0 cm2; bars represent 30-cm intervals. The means of logged basal areas that differed significantly between sites in a Tukey HSD test (P < 0.05) are indicated by italicized letters on the far right.

Treatment

At each site, we haphazardly selected 150 L. maackii individuals. Criteria for selection included a basal diameter >2 cm and a minimum distance of 2 m from the forest edge to ensure adequate surface area for herbicide application and to avoid any potential edge effects, respectively. We measured the basal stem diameters of all selected individuals and used these measurements to calculate total basal area. Individuals were then randomly assigned to one of 15 treatment combinations. These combinations consisted of a water-only control and various concentrations of herbicide and adjuvant, including five concentrations of glyphosate: 0 (0% v/v), 30 (6.1%), 60 (12.3%), 120 (24.6%), and 240 g L−1 (49.2%). Each concentration was paired with three concentrations of 2XL (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA): 0, 25, and 50% (v/v). We used generic glyphosate (Alligare Glyphosate 5.4, Opelika, AL, USA) with no surfactants or other additives.

Each treatment was premixed in spray bottles and applied on July 30, 2019, which was 8 d after and 13 d before a rain event. Temperatures ranged between 11 and 32 C during this period. All stems on each individual were cut horizontally approximately 10 cm above ground level with a chainsaw. Application of the assigned mixture occurred immediately after the cut was made. The vascular zone was completely treated to ensure full coverage of the herbicide mixture and to achieve maximal entry into the vasculature, and thus transport to the root system. The application volume of the treatment per stump was approximately 3.5 to 4.5 ml of solution per ∼6.5 cm of basal diameter per stem, based on a general estimate. This methodology closely matches the application technique commonly used by land managers (Frank et al. Reference Frank, Saunders and Jenkins2018).

Resprouting stems were measured once in early November of the same year as the initial treatment (2019; ∼95 d after treatment) and again in July of the following year (2020; ∼357 d after treatment). The number of resprouts and length of the longest resprout, measured from tip to the base of the resprout on the cut stump, were recorded. Additionally, we recorded the occurrence of deer browse. Browse rates were low both years (same year: 9%; following year: 5%) and similar between sites.

Statistical Analyses

Due to the abundance of zero values (no resprouting), a negative binomial regression model predicting the number of resprouts was constructed for each year (lme4 package in R; Bates et al. Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015), which included fixed effects of total basal area of each individual, glyphosate dosage, 2XL dosage, and the interaction between glyphosate and 2XL dosages, as well as site as a random effect. For all models, α = 0.05. We checked for an overdispersion assumption using a log-likelihood comparison between the full negative model and a Poisson model, with the same variables (same year: df = 18, P < 0.001; following year: df = 18, P < 0.001), and a chi-square test on the overdispersion ratio (same year: ⓒ = 3.44, P < 0.001; following year: ⓒ = 3.46, P <0.001). Results confirmed that the data were overdispersed and that the negative binomial distribution was appropriate.

The overall significance of the full negative binomial model was checked through a log-likelihood test, comparing it with a null model. The significance of interaction effects was also tested through a log-likelihood test by comparing the full model to a negative binomial regression that included the same variables except the interaction effect between glyphosate and 2XL dosages. The full model was significantly better than the reduced model, indicating that the interaction between glyphosate and 2XL was important in predicting resprouting. The previous two checks were confirmed through comparisons of the Akaike information criterion (AIC) for each model. Using the full negative binomial regression model, we performed pairwise comparisons between all combinations of glyphosate and 2XL for each year (emmeans and multcomp packages in R; Hothorn et al. Reference Hothorn, Bretz and Westfall2008; Lenth Reference Lenth2022). Response estimates of the number of resprouting stems and 95% confidence intervals were generated and displayed for these comparisons. Confidence intervals cannot be created for combinations of glyphosate and 2XL for which the model predicts zero resprouting stems, because there is no variance in the data. Thus, these estimates did not appear statistically different from other estimates, despite a clear biological and visually apparent difference. For resprouting stems, we ran a type III ANOVA (α = 0.05) comparing the heights of the tallest stem across glyphosate concentrations, 2XL volumes, and the interaction effect between glyphosate and 2XL dosages, with total basal area of L. maackii as a fixed effect.

A similar process was used to examine the relationship between basal diameter and glyphosate treatment and their effect on stump mortality as represented by the occurrence of any resprouting in the year following treatment. We fit a logistic regression with total basal area, glyphosate treatment, and an interaction between the two as fixed effects and site as a random effect. The model was then compared with a null model for overall significance, and we used a type II Walk chi-square test (Anova from the car package in R; Fox and Weisberg Reference Fox and Weisberg2019) to examine the significance of each fixed effect (α = 0.05).

Results and Discussion

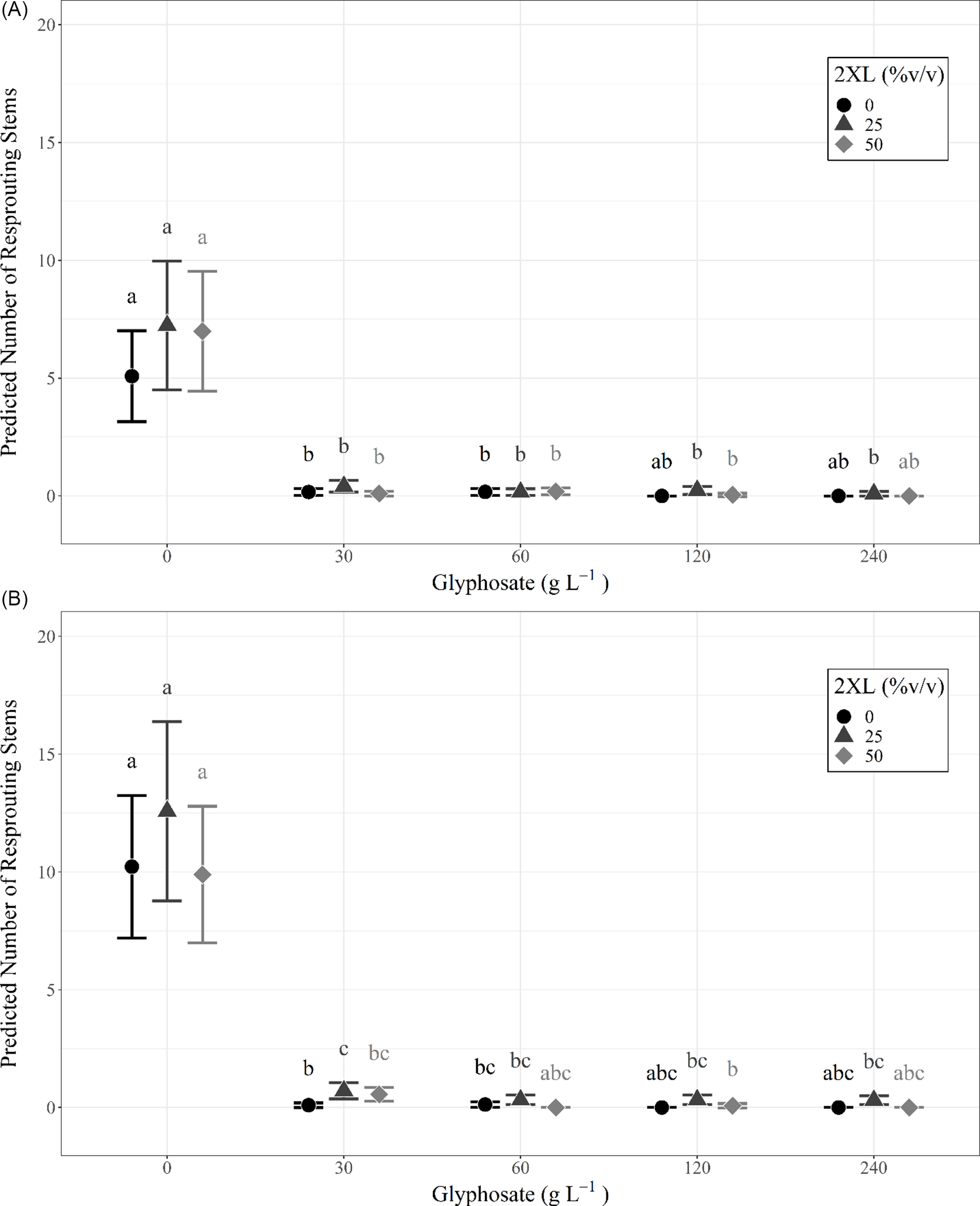

The number of resprouts on individual L. maackii stumps varied with treatment type, with those receiving glyphosate treatment exhibiting few resprouts, regardless of concentration. No effect on resprouting was observed with the addition of 2XL, irrespective of the concentration of either chemical. This trend was consistent for measurements in the same year as treatment (∼95 d after treatment) and in the following year (∼357 d after treatment) and can be seen in the predicted values from each year’s full negative binomial model (Figure 2; Table 1).

Figure 2. Predicted number of resprouting Lonicera maackii stems and 95% confidence intervals, based on the full negative binomial regression model for (A) the same year (∼95 d after treatment) as treatment and (B) the following year (∼357 d after treatment). The superscript letters of significance indicate significant differences (α = 0.05) in pairwise comparisons between all combinations of glyphosate and 2XL for each year. Confidence intervals could not be created for combinations of glyphosate and 2XL for which the model predicts zero resprouting stems, because there is no variance in the data.

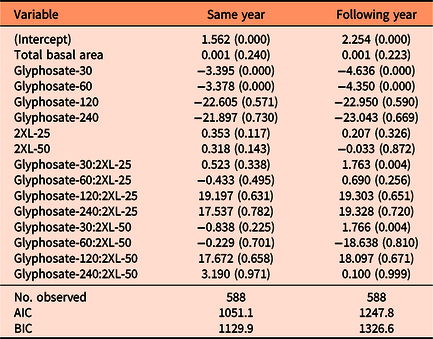

Table 1. Summary of the negative binomial models explaining the number of resprouting Lonicera maackii stems in both the same year (∼95 d after treatment) and the one following treatment (∼357 d after treatment). a

a Regression coefficients and P-values (in parentheses) are included for each variable. AIC, Akaike information criterion; BIC, Bayesian information criteria.

Both the same-year negative binomial model (df = 18, P < 0.001) and the model for the following year (df = 18, P < 0.001) were significant predictors of the number of resprouts when compared with null models. We also found that the interaction effect between glyphosate and 2XL significantly contributed to the model’s predictive ability in both the same year (df = 18, P < 0.001) and the following year (df = 18, P < 0.001). The AIC was lowest for the full negative binomial models (same year: 1,051.1; following year: 1,247.8) compared with the null models (same year: 1376.8; following year: 5095.8), reduced models (same year: 1,057.9; following year: 1,285.2), and Poisson models (same year: 1,175.2; following year: 1,416.5). This confirmed that the full negative binomial models were the most appropriate models for both years. The coefficient estimates from the negative binomial mixed-effects model revealed that 2XL only had nonsignificant or positive effects on the predicted number of resprouts in both years. Specifically, we observed a small but significant increase in the number of resprouts in the year following treatment when 30 g L−1 of glyphosate was mixed with a 25% volume of 2XL compared with no 2XL (Figure 2B).

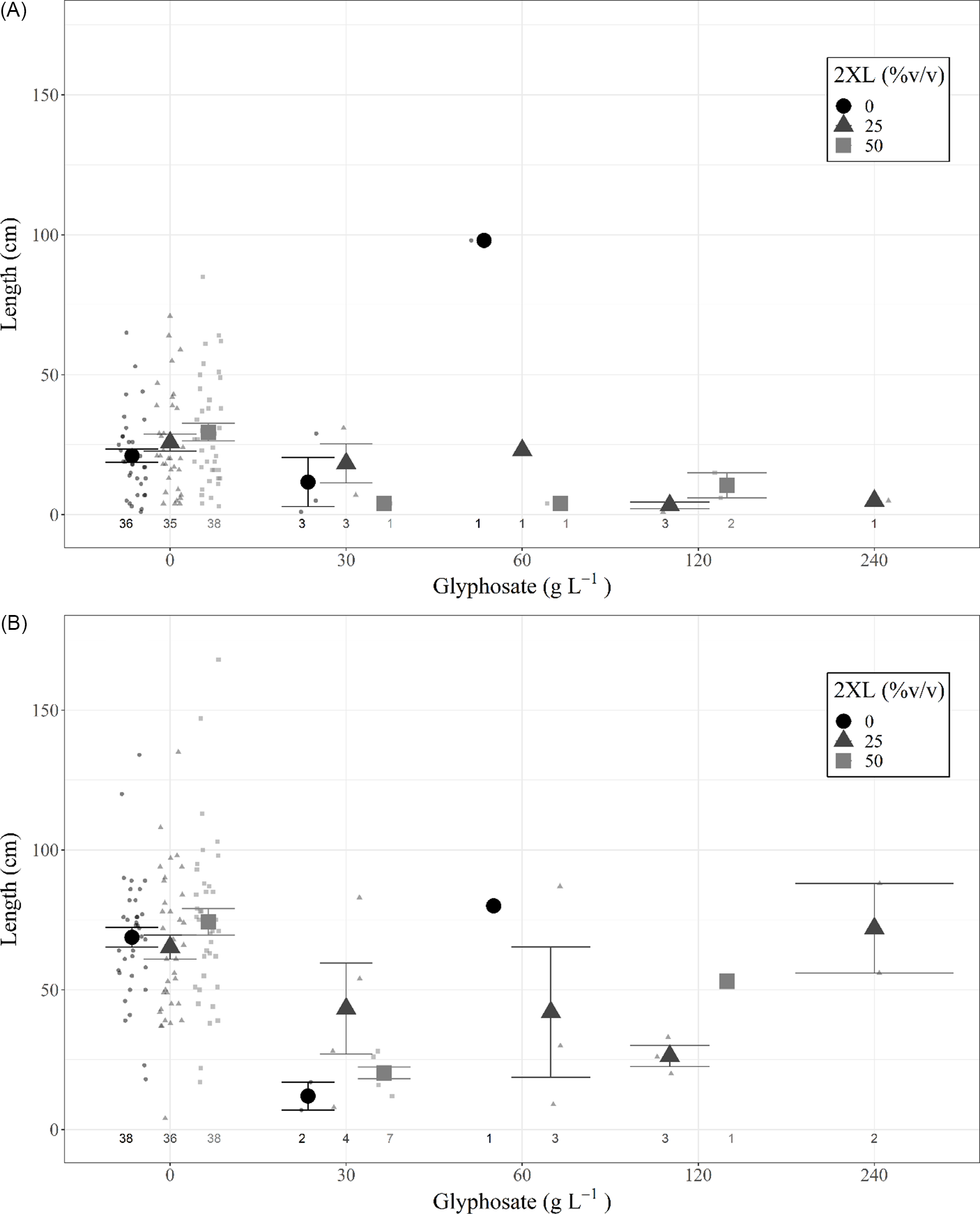

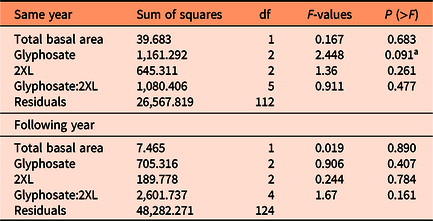

A type III ANOVA revealed no significant differences among any 2XL–glyphosate combinations in both the same-year resprout lengths (Figure 3A; Table 2) or in those for the following year (Figure 3B; Table 2), although the low number of resprouting stems in combinations containing glyphosate may have hidden any potential relationship. This provides additional evidence that 2XL did not meaningfully impact the control of L. maackii.

Figure 3. Length (mean and 95% confidence interval) of tallest resprouting Lonicera maackii stem (cm) of individuals that resprouted for (A) the same year as treatment (∼95 d after treatment) and (B) the year following treatment (∼357 d after treatment) across treatment types. Large symbols represent means, individual data points are displayed as smaller symbols of the same shape. The number of resprouting stems in each treatment group is displayed below each group; those groups with no resprouting stems are not displayed.

Table 2. Type III ANOVA results from comparisons of the tallest resprouting Lonicera maackii stem in the same year as treatment (∼95 d after treatment) and the following year (∼357 d after treatment).

a Glyphosate level had a marginally significant impact on the length of the longest resprouting stem in the same year.

Stump mortality was significantly predicted by our logistical regression when compared with a null model (df = 11, P <0.001). However, the examination of the individual fixed effects revealed that glyphosate treatment level alone (χ2 = 70.498, df = 4, P < 0.001) was statistically significant. Total basal area (χ2 = 0.054, df = 1, P = 0.816) and the interaction effect between total basal area and glyphosate treatment level (χ2 = 3.992, df = 4, P = 0.407) did not significantly improve the model’s prediction of stump mortality. Our measure of stump mortality was simply whether the stump possessed any resprouting stems in the year following treatment, but it is possible that some stumps would be able to resprout in later years. However, we found that only 3% of all treated stumps resprouted in the year following treatment when they did not display any resprouting in the same year of treatment. Of all the stumps that displayed resprouting in the following year (a total of 136), only 19 (14%) had not exhibited resprouting within the same year as treatment. Thus, we are relatively confident that stumps that have yet to resprout will not resprout in future years, though further research could be done into the year-to-year resprouting rates of L. maackii after treatment.

The primary goal of our study was to determine whether lower concentrations of glyphosate can effectively control an aggressive, nonnative shrub through the use of 2XL as an adjuvant. Interest in reducing the concentration of glyphosate used to control invasive plants addresses environmental (Busse et al. Reference Busse, Ratcliff, Shestak and Powers2001; Gill et al. Reference Gill, Sethi, Mohan, Datta and Girdhar2018; Tsui and Chu Reference Tsui and Chu2003;) and human health (Bai and Ogbourne Reference Bai and Ogbourne2016; International Agency for Research on Cancer 2015) concerns, as well as reservations expressed by private landowners (Howle et al. Reference Howle, Straka and Nespeca2010; Ma et al. Reference Ma, Clarke and Church2018). We found that all tested concentrations of glyphosate were highly effective at preventing the resprouting of L. maackii from cut stumps and that lower concentrations of glyphosate were as inhibitory as higher concentrations.

Similar studies using the cut stump method of control utilized higher concentrations of glyphosate on L. maackii. Hartman and McCarthy (Reference Hartman and McCarthy2004) used a 50% glyphosate solution, which is roughly equivalent to 244 g L−1 of glyphosate. While they saw similarly high levels of control (94% mortality), our study achieved equivalent levels of control with 30 and 60 g L−1. Other studies have shown 90% to 100% efficacy in preventing resprouting within the year of treatment using ∼88 g L−1 glyphosate (18%) in the cut stump method for controlling L. maackii, which is similar to what we achieved with our lower concentrations (Owen et al. Reference Owen, McDonnell, Mounteer and Todd2005; Schulz et al. Reference Schulz, Wright and Ashbaker2012). Use of the cut stump method with a 20% to 25% concentration of glyphosate (98 to 122 g L−1) is widely recommended to private landowners as a control technique (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Manning and Enloe2013; Smith and Smith Reference Smith and Smith2010). However, our results suggest that a lower concentration could achieve the desired level of control across our tested range of basal areas.

Similar studies on other invasive shrubs provide some support for lower glyphosate concentrations. For example, lower concentrations of glyphosate have been used to effectively control a closely related invasive species, Morrow honeysuckle (Lonicera morrowii A. Gray; Mervosh and Gumbart Reference Mervosh and Gumbart2015). In that study, ∼41 g L−1 was as effective as ∼205 g L−1 in completely preventing resprouting in the cut stump method of treatment. However, another study had less success in controlling L. morrowii with a moderate concentration of glyphosate (∼98 g L−1), particularly when treatments were applied in the autumn (Love and Anderson Reference Love and Anderson2009). A concentration of 120 g L−1has been successfully used to control another problematic invasive shrub: Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense Lour.; Enloe et al. Reference Enloe, O’Sullivan, Loewenstein, Brantley and Lauer2018).

For the control of invasive shrub species, glyphosate concentrations of 20% to 25% (98 to 122 g L−1) applied in the late summer or early autumn are typically recommended to land managers and private landowners (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Manning and Enloe2013; Smith and Smith Reference Smith and Smith2010). However, the results of our study, and those of similar studies that examined control techniques for invasive shrub species, suggest that reevaluating these recommendations may be warranted, given that effective control (as evidenced by the inhibition of resprouting stems) can be achieved with lower concentrations of glyphosate. Because our study was conducted on one species during a single season under relatively dry and temperate conditions, our findings should be replicated across seasons of the year and invasive shrub species and under varying environmental conditions. Nonetheless, based on our results, concentrations of glyphosate as low as 30 to 60 g L−1 can be effective at preventing the resprouting of L. maackii, which could reduce the expense of treatments while also potentially alleviating the concerns of landowners about non-target effects of the herbicide.

Our study was the first to evaluate the effectiveness of cellulase as an herbicide adjuvant. Contrary to our predictions, we found no evidence that 2XL provides any meaningful benefit when used in conjunction with glyphosate. Our review of the literature found no published reports describing the mechanism by which glyphosate enters the vascular tissue(s) when applied to the stumps of woody plants. However, it has been suggested that phosphate transporters play a role in the uptake of glyphosate when applied as a foliar spray to herbaceous plants (Gu et al. Reference Gu, Chen, Sun and Xu2016; Misson et al. Reference Misson, Raghothama, Jain, Jouhet, Block, Bligny, Ortet, Creff, Somerville, Rolland, Doumas, Nacry, Herrerra-Estrella, Nussaume and Thibaud2005). Concerning the foliar application of glyphosate on woody plants, Pereira et al. (Reference Pereira, Tayengwa, Alves and Peer2019) described how phosphate transporters embedded in the cell membranes of rose gum (Eucalyptus grandis W. Hill ex Maid.) may facilitate glyphosate absorption into the tree’s vascular tissue from a foliar application. Additionally, recent research suggests that an ATP-binding cassette transporter is the primary means by which glyphosate enters the cytoplasm of a cell (Pan et al. Reference Pan, Yu, Wang, Han, Mao, Nyporko, Maguza, Fan, Bai and Powles2021). Understanding glyphosate’s pathway and uptake efficiency into woody vascular tissue on a physiological level may be a critical next step in finding more effective adjuvants.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the National Science Foundation for funding (STTR grant no. 1738503) and a partnership with EntoBio LLC. Thanks to Katherine Wynne for help with the models. Purdue University’s Department of Forestry and Natural Resources provided research resources and access to the study area. Specific thanks to Brian Beheler for guidance and support and Garrett Pell, Ed Oehlman, and Grace Warble for their assistance with fieldwork. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.