The practice of holding states responsible was commonly understood as punitive until shortly after the First World War. Some acts of state, such as aggression and piracy, were considered to be crimes; wars and sanctions were considered to be legitimate punishments.Footnote 1 But under current international law, only individuals are subject to criminal responsibility and punishment. The Nuremberg Tribunal's oft-quoted statement that ‘[c]rimes against international law are committed by men, not by abstract entities’ remains the rule.Footnote 2 States can be responsible for ‘wrongful acts’ and ‘serious breaches’, and they can owe reparations, but they are not subject to criminal responsibility or punishment.Footnote 3

Some political theorists, philosophers, International Relations (IR) scholars, and lawyers have recently revived the idea of state crime.Footnote 4 They argue that states should be held criminally responsible for atrocities such as aggression and genocide, much as corporations are held criminally responsible in domestic law. Critics reply that the idea of state crime is conceptually confused: ‘it is untenable to treat [states’] legal and moral personality as anything other than metaphorical or “as-if”; they therefore can neither commit crimes nor incur punishment’.Footnote 5 States cannot commit crimes because they do not have intentions, and they cannot be punished because they cannot suffer. In addition, both proponents and critics of state crime worry about ‘the danger of harming innocent individuals while ostensibly punishing delinquent states’.Footnote 6 The debate about state crime revolves around two issues – intent and punishment – that have dominated the more general debate about corporate criminal responsibility for decades or even centuries.Footnote 7

In the interest of moving the debate forward, I bracket the issues of corporate intent and punishment. I assume for the sake of argument that the concept of corporate crime is sound: that corporate entities can be genuine agents, and that they can sensibly be punished. I also put aside the more general problem of enforcing international law. Instead, I focus on two problems with holding states criminally responsible that have received much less attention. The first I call the Agency Problem: only agents can be held criminally responsible, but many states fail to meet the conditions for corporate agency. The second I call the Temporal Problem: since the most serious international crimes are not subject to a statute of limitations, the argument for state crime implies that states should be punished for decades-old or even centuries-old crimes. These problems do not undermine the conceptual possibility of state crime.Footnote 8 By starting from the assumption that corporate entities can be genuine agents, I have already granted that it is conceptually coherent to hold states criminally responsible. What the Agency Problem and Temporal Problem show is the argument for state crime faces formidable challenges even when its central premises have been granted. These two problems are best understood as critiques rather than as decisive objections; they limit the scope of state crime and pose difficult tradeoffs.

In any case, I argue, it is unnecessary to hold states criminally responsible. A wide range of responses to atrocity can be justified in purely reparative terms, including compensation, official apologies, lustration, and institutional reform. And if an outlet for punishment is necessary in the international order, then it can already be found in criminal trials of individuals. I thus defend the existing ‘division of labour’ between international criminal law, which is primarily for punishing individuals, and state responsibility, which is wholly reparative. Defending the status quo is a larger contribution to the debate than it may seem. The current system of international responsibility has been subjected to sustained criticism and is in need of a better defence. Partisans of the current system have so far provided only a negative defence. They argue against extending criminal responsibility to the state, but they do not provide an argument for the current system, or a positive vision of what non-criminal state responsibility should be.

The paper has four main sections. The first section presents the strongest and most up-to-date arguments for corporate criminal responsibility. In addition to the philosophical literature on corporate agency, I draw from recent jurisprudence and legal history on corporate crime. The second section describes the Agency Problem, which presents a barrier to any simple extension of corporate crime to the state. Many states do not meet the conditions for corporate agency, and the others meet the conditions only in a limited sense. The third section describes the Temporal Problem. I show that the argument for state crime paves the way for forms of ‘historical punishment’ that few proponents of state crime would be willing to accept. The fourth section argues that abandoning the idea of state crime would be no great loss. Most responses to atrocity can be justified in reparative terms, and international criminal law already provides an outlet for punishment.

The case for corporate criminal responsibility

A crime has two elements: actus reus (guilty act) and mens rea (guilty mind). In order for an agent to be criminally responsible, it must have (1) performed an illegal act and (2) done so intentionally.Footnote 9 There are some exceptions, such as strict liability offences.Footnote 10 There are also some structural or institutional preconditions for criminal responsibility, such as the need for an impartial authority that can make criminal judgments against the relevant agents.Footnote 11 But it is widely agreed that these two conditions – act and intent – are necessary. At a minimum, then, an entity must be capable of both actus reus and mens rea in order to be fit for criminal responsibility.

The theory of corporate moral agency provides a powerful justification for holding groups responsible. The core idea is that groups with certain kinds of internal structures constitute genuine agents, over and above their individual members. Whereas an ‘aggregate’ group, such as a mob, is merely a collection of individuals whose wills converge or coincide, a ‘conglomerate’ or ‘corporate’ group has a centralized decision-making procedure that combines the wills of its members into an overarching corporate will.Footnote 12 As Toni Erskine argues, a corporate group is ‘capable of acting and knowing in a way that is analogous – but not identical – to that of (most) individual human beings’.Footnote 13 The theory of corporate moral agency has been applied to organizations of various kinds, including business corporations, churches, universities, nongovernmental organizations, rebel groups, and, as I discuss below, states.Footnote 14

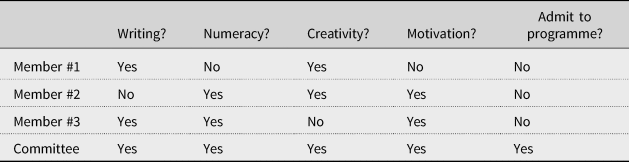

The claim that groups can have wills or intentions tends to provoke skepticism. However, philosophers have demonstrated that collective intentionality is less mysterious than it seems.Footnote 15 Collective intentions ‘holistically supervene’ on individual intentions: the former are composed of but not reducible to the latter.Footnote 16 Deborah Tollefsen uses the example of a PhD admissions committee to illustrate how collective intentions can emerge from the structured combination of individual intentions.Footnote 17 The admissions procedure says that applicants must demonstrate excellence in all four areas – writing, numeracy, creativity, and motivation – in order to be admitted, and the committee uses majority voting to decide whether the applicants meet the criteria. The results for Molly's application are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Tollefsen's admissions committee

The vote produces a peculiar result. Although a majority of the committee thinks Molly meets each criterion for admission, none of the individual committee members think Molly meets all of the criteria. The committee intends to admit Molly to the PhD programme despite the fact that none of its members has this intention: ‘We intend to admit Molly’ is true for the committee even though ‘I intend to admit Molly’ is not true for any individual member. The admissions procedure thus gives rise to a collective intention that cannot be ascribed to any individual. The holistic supervenience account of collective intentionality implies that collective intentions are irreducible to individual intentions even though they are entirely made up of individual intentions.

If we accept that corporate groups can have intentions, even in this very thin sense, then corporate criminal responsibility is a short step away. As Philip Pettit argues,

corporate bodies are fit to be held responsible in the same way as individual agents, and this entails that it may therefore be appropriate to make them criminally liable for some things done in their name; they may display a guilty mind, a mens rea, as in intentional malice, malice with foresight, negligence, or recklessness.Footnote 18

Corporations are often said to act – to commit fraud, or to pollute the environment – and to do so intentionally. It is common and natural to say that ‘the company intentionally misled its customers’ or that ‘the company deliberately violated environmental law’.Footnote 19 Criminal corporate actions and intentions seem to demand corporate criminal responsibility.

The idea of corporate agency has recently been taken up in law and jurisprudence.Footnote 20 The legal literature both draws from and complements the philosophical literature. First, the idea of corporate agency places corporate criminal law on a firm ontological footing and thereby eliminates the need for the ‘fiction theory’ of the corporation. Second, the legal literature helps to explain how, in practice, corporations are constituted as agents. As William Thomas shows, corporations became agents under the criminal law only when corporate law began to regulate their internal structures in a particular way. Corporations are fit to be held criminally responsible because ‘corporate law provides corporations with the kind of sophisticated internal structure necessary to establish their eligibility for personhood’.Footnote 21

It may seem straightforward to extend the argument for corporate criminal responsibility to the state. Like corporations, states have complex decision-making procedures that allow them to deliberate, to set goals, and to act according to those goals. It is therefore plausible to conclude that states should also be held criminally responsible.Footnote 22 As Avia Pasternak argues, ‘if states are corporate moral agents, they too could be subjected to a process of criminal accountability, where they are put to trial, publicly condemned for their crimes, and (where appropriate) punished’.Footnote 23 The argument for holding states criminally responsible seems even more compelling in light of the fact that the most serious international crimes – genocide, aggression, war crimes, and crimes against humanity – are usually perpetrated, or at least aided and abetted, by states. States commit genocide, and they do so intentionally; and genocide is clearly a crime; so it seems that genocidal states must be criminals.Footnote 24

The agency problem

Extending corporate criminal responsibility to the state is not as simple as it sounds. Even if states can be corporate agents, there is no guarantee that any particular state will meet the conditions for corporate agency. It turns out that many of the states that commit criminal actions are not ‘fit to stand trial’ in the first place. The Agency Problem places limits on the kinds of states that can be held criminally responsible and on the kinds of measures that can be used to punish states.

Before turning to the ways in which some states fail to meet the conditions for corporate agency, it is helpful to turn back to corporations. As Thomas shows, developments in corporate law made corporate criminal responsibility possible.

The expanded availability of the corporate form, the relaxing of corporate-purpose requirements, and the general liberalization of corporate law during and immediately following the 19th century enabled the creation and proliferation of corporate persons sophisticated enough to be eligible for legal personhood under criminal law, and specifically to satisfy criminal law's mens rea requirement.Footnote 25

Corporations do not meet the conditions for agency spontaneously. Instead, ‘corporate law plays a crucial role in making possible corporate-criminal liability by designing corporations to be the kind of things that can qualify as persons’.Footnote 26 In particular, corporate law imposes a decision-making structure that is conducive to the formation of a unified and (more or less) consistent set of corporate attitudes and intentions – like the admissions committee in the previous section. Obviously, not all corporations are genuine agents; shell companies are merely pseudo-agents. But most corporations do meet the conditions for agency, and this is primarily because corporate law ensures that they function as agents.

However, there is no ‘international corporate law’ that regulates the internal structures of states. There is consequently no guarantee that states will meet the conditions for corporate agency.

In order to determine which states do or do not meet the conditions, it is first necessary to determine what is meant by ‘the state’. Proponents of the idea that the state is a corporate agent all agree that the state is a particular kind of organization or institution: a group of human beings who act together according to a common decision-making procedure.Footnote 27 There obviously cannot be a state without members or without decision-making rules. The main difficulty is how to determine the state's membership. Holly Lawford-Smith distinguishes two models of the state.Footnote 28 The ‘citizen-exclusive’ state includes only government officials (from presidents to low-level bureaucrats), whereas the ‘citizen-inclusive’ state includes both government officials and the voting public. One well known citizen-exclusive account comes from David Easton, who argues that the state is ‘no more than a substitute term for the political authorities’.Footnote 29 Theorists of corporate agency, and political theorists more generally, tend to employ citizen-inclusive accounts of the state. For instance, Toni Erskine argues that ‘the membership of the state – in the form of its citizens – is not determinate’.Footnote 30 I argue, first, that many actual states fail to meet the conditions for corporate agency on either model; and second (following Lawford-Smith), that the states that do meet the conditions for corporate agency do so only on the citizen-exclusive model.

Failed states fail to meet the conditions for corporate agency on either model. What makes them ‘failed’ is that their decision-making procedures are too weak or chaotic to produce a relatively coherent set of corporate intentions. In Peter French's terms, they are more like ‘aggregates’ than ‘conglomerates’.Footnote 31 In addition, as Erskine argues, there are many ‘quasi-states’ that lack the freedom or independence to fully exercise their moral agency.Footnote 32 Although a quasi-state may have a centralized decision-making procedure, its responsibility for its decisions is mitigated to the extent that these decisions are determined by other states or by outside forces.

Dictatorships also fail to meet the conditions for corporate agency on either model. As it turns out, many proponents of state crime would agree. Anthony Lang argues that ‘when a dictatorial regime commits a crime, it makes more sense to attribute that crime to the head of state, in that the policy results from his individual intention’.Footnote 33 Similarly, Pettit argues that a dictatorship ought to be treated ‘not as a group agent that operates via an authorized individual, but as an individual agent whose reach and power is extended and amplified by the members of the authorizing group’.Footnote 34

The crucial but unstated premise here is that the agent in relation to an action is the source of the corresponding intention. For instance, I am the agent in relation to writing this paper because I am the source of the intention to write it. As Lawford-Smith points out, it would be a mistake to treat a whole group as an agent simply because there is a source of intentionality somewhere within the group.Footnote 35 This is easiest to see in a small-scale example. Suppose that there are four people rowing down a river in a boat. If the rowers come to a fork in the river, and they decide together to take the right fork, then the group of four is the source of the intention to take the right fork. They would all be to blame if the right fork led them over a waterfall. But if one rower forces the boat to the right, or coerces the others into going right instead of left, then he is the source of the intention to take the right fork. He would therefore be solely to blame if taking the right fork led to disaster. The fact that the other three remain in the boat, and that they continue to row, does not make the decision to take the right fork ‘theirs’. In short, the locus of agency in a group – and hence the appropriate target for criminal responsibility – is the source of the intentionality that animates the group's actions.

According to Pettit's and Lang's logic, then, a dictatorship is analogous to the boat that is steered by a single rower. The source of the state's intentionality, and hence the appropriate target for criminal responsibility, is the dictator qua individual.Footnote 36 The citizen-inclusive state is not a corporate agent, because citizens in a dictatorship are just ‘passengers’ on the ship of state. The citizen-exclusive state is not a corporate agent either, because public officials are primarily instruments of the dictator. Although police officers, soldiers, and civil servants execute the actions of the dictatorship, they are not the source of its intentions; they ‘row’ but do not ‘steer’. (As I explain shortly, matters are different in bureaucratic-authoritarian states, including those that are superficially dictatorial.) Dictatorships can thus be understood as pseudo-corporate agents, or individual agents pretending to be corporate agents.

The case of oligarchies is more complicated and varied. Scholars of authoritarianism distinguish ‘simple military authoritarian regimes’, which are run from the top by a small junta, ‘from bureaucratic authoritarian regimes’, which are run by ‘a powerful group of technocrats’ in conjunction with a larger bureaucracy.Footnote 37 In neither type of oligarchy is the citizen-inclusive state an agent, for the obvious reason that the decision-making procedure does not include citizens. Citizens in either kind of oligarchy, like citizens in a dictatorship, are ‘passengers’ on the ship of state. But whether the citizen-exclusive state counts as a corporate agent depends on the kind of oligarchy.

In a ‘simple’ oligarchy, the source of intentionality is the junta rather than the citizen-exclusive state as a whole. Soldiers and officials in this kind of state are largely instruments of the junta. To adapt Pettit's phrasing: we could think of a military state not as a group agent that operates via a junta, but as a junta whose reach and power is extended and amplified by government officials and the military. Or to adapt Lang's phrasing: when a military state commits a crime, it makes more sense to attribute that crime to the junta, in that the policy results from its intention (as opposed to the intention of the whole citizen-exclusive state). Again, the fact that there is intentionality somewhere within the state does not make the whole state an agent. The appropriate target for criminal responsibility is the source of intentionality, or the locus of the relevant mens rea. So if the source of intentionality behind ‘the state's’ decisions is a small subgroup, such as a junta, then criminal responsibility should be assigned to that subgroup.Footnote 38

In a ‘bureaucratic-authoritarian’ state, the source of intentionality does seem to be the citizen-exclusive state. The fact that a state is hierarchically structured does not necessarily mean that intentionality arises solely from the top of the hierarchy. It would be a mistake to assume that the technocratic elite is the only corporate agent or that the bureaucracy is only an instrument of the technocrats. Insofar as the bureaucracy contributes to the formation (rather than merely the execution) of corporate intentions, it is also part of the relevant corporate agent. The source of intentionality in a bureaucratic-authoritarian state will typically be a complex of individuals and organizations that is roughly coextensive with the citizen-exclusive state. In some oligarchies, then, the citizen-exclusive state is a corporate agent.Footnote 39

A fortiori, in democracies, the citizen-exclusive state is a corporate agent. The legislature, executive, courts, and civil service are all corporate agents in their own right, but their actions are coordinated in such a way that they can act together as a single agent.Footnote 40 The crucial question is whether the citizen-inclusive state counts as a corporate agent in a democracy. Many theorists of corporate agency seem to think so. Lang argues that ‘[i]f a state is democratic and initiates a policy that leads to a crime, it makes more sense to attribute that crime to the [citizen-inclusive] state qua agent’.Footnote 41 Anna Stilz argues that if citizens democratically authorize the state, then they are members of the state qua corporate agent and should therefore share liability for its actions.Footnote 42 Democracy seems to make the whole ‘people’ the source of intentionality, and hence the appropriate target for criminal responsibility.

However, Lawford-Smith has recently challenged the longstanding assumption that the democratic ‘state-as-a-whole’ is a corporate agent. Although the citizenry as a whole is capable of occasional ‘joint action’ – namely, voting – this is not sufficient for corporate agency.

From the fact that there is coordinating infrastructure for voters to do one thing together, namely vote (elect a government every 3 years or so), it does not follow that there is coordinating infrastructure for them to act together in general.Footnote 43

Voting does not make the citizenry as a whole the source of intentionality behind the state's actions; voting is merely a way to ‘contract agency out to a subgroup, namely government [i.e. the citizen-exclusive state]’.Footnote 44 In terms of agency, then, a democratic state is more similar to a bureaucratic-authoritarian state than it first appears. The corporate agent in each case is the citizen-exclusive state.

So far, I have argued that failed states, dictatorships, and simple oligarchies do not count as corporate agents on either model of the state, and that bureaucratic-authoritarian and democratic states count as corporate agents only on the citizen-exclusive model. Two important implications follow.

First, many states are not fit to be held criminally responsible. Failed states cannot form mens rea at all, and the mens rea behind the actions of dictatorships and simple oligarchies are really the intentions of individuals or small subgroups within the state. Only bureaucratic-authoritarian and democratic states can satisfy the mens rea condition for criminal responsibility, and then only on the citizen-exclusive model.

The fact that some states are not fit to be held criminally responsible does not undermine the argument for state crime, any more than the fact that some human beings are not fit to be held criminally responsible undermines domestic criminal law. But the Agency Problem does significantly restrict the scope of state crime, because atrocities are often committed by states that fail to meet the conditions for corporate agency. Many of the worst crimes have been committed by dictatorships: Germany under Hitler, Rwanda under Sindikubwabo, Cambodia under Pol Pot, Iraq under Hussein, Liberia under Taylor – the list could be expanded ad nauseum. It is true, of course, that democracies also commit crimes. As Stilz argues, the United States and the United Kingdom are guilty of waging an aggressive war against Iraq in 2003.Footnote 45 But if dictatorships are not fit to be held criminally responsible, then the scope of state crime is fairly narrow. And if, as I have argued, simple oligarchies are also unfit, then the scope of state crime is even narrower.

The second important implication of the argument so far is that only the citizen-exclusive state can legitimately be punished. There are many ways of trying to punish a state, including war, economic sanctions, dissolution, forced reform, fines, and ‘naming and shaming’.Footnote 46 The problem is that many of these measures will inevitably inflict suffering on the citizens of the target state. Since only citizen-exclusive states meet the conditions for corporate agency, states should be punished only in citizen-exclusive ways.

The suffering inflicted on citizens that results from punishing their states could be considered collateral damage or ‘overspill’ rather than punishment per se.Footnote 47 However, as Bill Wringe argues, the suffering inflicted on citizens often does amount to punishment. According to his expressive theory, punishment is (1) harsh treatment (2) in response to wrongdoing (3) to express societal condemnation.Footnote 48 War or sanctions against a state inevitably impose harsh treatment on its citizens. So if war or sanctions are undertaken to condemn wrongdoing, then the harsh treatment imposed on citizens is implicitly punitive, since it meets the three essential conditions for punishment.Footnote 49 Similarly, though less obviously, coercive reform or dissolution of a state would often constitute punishment of its citizens. It is true, as Rousseau said, that ‘it is possible to kill the State without killing a single one of its members’.Footnote 50 But to coercively dissolve or reform a state would be to deny self-determination to its citizens, which would surely count as harsh treatment. Likewise, and more obviously, large fines against a state would inevitably inflict harsh treatment, and hence punishment, on its citizens. These measures would entail punishment of citizens not just according to Wringe's expressive theory, but according to any theory that takes harsh treatment in response to wrongdoing to be constitutive of punishment.Footnote 51

Here lies the central problem: only the citizen-exclusive state can be held criminally responsible, since only the citizen-exclusive state is a corporate agent, but many punitive measures against states are inevitably citizen-inclusive.

The range of citizen-exclusive ways of punishing the state is limited. Wringe suggests that the most promising method of punishing a state is to impose ‘status measures’, which downgrade the target state's status in the ‘international community’ or restrict some of the target state's rights and privileges.Footnote 52 Cultural boycotts and suspensions of membership in international organizations are paradigmatic status measures. Wringe argues that ‘status measures need not necessarily involve harsh treatment of the citizens of a state’, though he does acknowledge that ‘they will often involve actions which harm the interests of the citizens of a state against which they are taken’. Fines against a state could also be citizen-exclusive, provided that they are relatively small. For instance, a fine of $10 million against the United States would be so small relative to the size of the federal budget that the effect on any individual citizen would be negligible.Footnote 53 ‘Smart sanctions’ against state officials are another way of punishing the citizen-exclusive state. There may well be other ways. The important point here is that if only the citizen-exclusive state counts as a corporate agent, then several major options for punishing the state are ruled out: war, economic sanctions, and large fines. The Agency Problem thus limits both the kinds of states that can be held criminally responsible and the kinds of measures that can be used to punish states.

There is one formidable response to the Agency Problem. Even if agency is a conceptual precondition for criminal responsibility, it might also be the case that criminal responsibility helps to bring agents into being. As Lang argues, ‘punitive practices not only punish agents[;] they construct agents … punishment creates norms, but it also creates the very agents who can be held responsible for such violations’.Footnote 54 It is possible that the agent-constituting function, which is served by corporate law in the domestic realm, could be served by punishment in the international realm. Christian List and Philip Pettit argue that holding a deficient agent or non-agent responsible can ‘responsibilize’ it, or transform it into an agent that is fit to be held responsible. Although young children are not full moral agents, holding them responsible despite their lack of moral agency helps them to develop into full moral agents. Similarly, although a dictator might actually be the culpable agent, holding the whole state responsible for his crimes might give citizens an incentive to refashion the state into a genuine corporate agent.Footnote 55 The solution to the Agency Problem could thus be to turn the problem on its head. The way to transform a deficient state into a well-constituted agent might be to punish the state despite its lack of agency.

It is true that holding a deficient state responsible can sometimes have a developmental effect. For instance, public debt helped to transform the United States from a loose confederation into a federal union. Although the United States at first failed to function as a competent agent, since the individual states were unable to act together to service the national debt, the fact that the United States had debt that needed to be serviced became a reason to develop a more centralized decision-making structure. As Alexander Hamilton famously argued, ‘the jurisdiction of the Union, in respect to revenue, must necessarily be empowered to extend … for the payment of the national debts contracted’.Footnote 56 In List and Pettit's terms, the debt helped to ‘responsibilize’ the nascent United States.

However, it is far from clear that punishment is an effective way of responsibilizing states. The literature on economic sanctions casts doubt on the idea that punishing states would have an agency-developing effect. First of all, economic sanctions are not very effective in general, even for inducing modest changes in policy in the target state. At best, sanctions achieve their stated objectives about one-third of the time; at worst, they rarely achieve their stated objectives.Footnote 57 Second, sanctions are even less effective at inducing regime change and, in some cases, actually help the target regimes to consolidate power.Footnote 58 Third, ‘sanctions are less likely to succeed against a nondemocratic target than against a democratic target’.Footnote 59 Deficient corporate agents are thus the least likely to respond to sanctions. Even if debts and treaty obligations tend to have an agency-developing effect, as in the early United States, it is doubtful that sanctions have this effect.

Of course, there are other ways in which states could be punished: fines, war, occupation, forced reform, dissolution, or status measures. The fact that sanctions are not effective means of responsibilizing states does not necessarily mean that other punitive measures would also be ineffective. As it stands, there is insufficient evidence, but the literature on corporate punishment does not bode well either: ‘corporate criminal punishment has roundly failed’, even at the comparatively modest task of deterring misconduct.Footnote 60 Until there is some evidence that punishing states would have an agency-developing effect, the Agency Problem remains. Since there is no ‘international corporate law’ that regulates the internal structures of states, many states fail to meet the conditions for corporate agency, and hence for criminal responsibility. The states that do meet the conditions are only citizen-exclusive agents, and therefore can legitimately be punished only in citizen-exclusive ways.

The temporal problem

How far back should the crimes of states be prosecuted? In the case of individual crimes, the human lifespan marks the outer limit: criminal responsibility dies with the criminal. But the Temporal Problem is far more troublesome for state crimes, because states have indefinite lifespans. In this section, I show that it is difficult to justify a time-limit on the prosecution and punishment of states. The argument for state crime paves the way for forms of ‘historical punishment’ that most of its proponents would be unwilling to accept.

There is no statute of limitations on the most serious international crimes, such as genocide and crimes against humanity. The principle that these crimes are ‘imprescriptible’, or not subject to time-limits, is well-established in international law and in many domestic legal systems.Footnote 61 Individual moral agents can be punished for these crimes as long as they live. Former Nazis, and even guards at concentration camps, continue to be punished for what they did 75 years ago. If states are moral agents, which they must be if they are to be held criminally responsible at all, then justice seems to demand that they be punished for atrocities that they committed when they were ‘young’. For instance, the United States should be punished for slavery. Although it has undergone many changes in population, territory, and government, it is still the same agent: ‘The young US with five million and the present US with [327 million] of inhabitants is, of course, the identical state in law’.Footnote 62 Corporate agents persist despite changes in their constituents, just as human agents persist despite changes in their cells.Footnote 63

Bare consistency would require that the United States be punished for slavery. Since the United States celebrates its past achievements, such as its victory in the War of Independence, then the United States should own up to its past crimes. It would be inconsistent for the state to take credit for its achievements without taking responsibility for its wrongdoing. And if states are subject to criminal responsibility, then the United States does not just owe reparations for slavery; it ought to be punished for slavery. The mere passage of time surely cannot wash away the crimes of slavery, colonialism, or genocide.

Few proponents of state crime would be willing to accept the implication that states should be punished for historical crimes. Even the most ardent proponents of historical reparations would probably balk at the idea of historical punishment. Perhaps this is because historical punishment looks like punishment of the innocent, or guilt by association. As I explained in the previous section, it is difficult to punish a state without effectively punishing its citizens, many of whom are innocent.Footnote 64 The risk of punishing the innocent would be far greater in cases of historical crime, in which the members of the citizen-exclusive state – government officials – are as blameless as citizens. Present-day government officials could not possibly be culpable for historical crimes, for the simple reason that they were not alive when the crimes were committed. So to punish states for historical crimes, even in citizen-exclusive ways, would be to punish the innocent. Of course, citizens and government officials might inherit reparative responsibilities for historical injustices, especially if they have inherited benefits.Footnote 65 But inherited culpability would be a form of guilt by association. In any case, the fact that calls for historical reparations are common, whereas calls for historical punishment are not, suggests that there is some widespread intuition against historical punishment.

There are several ways that proponents of state crime could try to avoid the implication that states should be punished for historical crimes. First, it could be argued that historical crimes should not be punished if the character of the perpetrator state has fundamentally changed. Mihailis Diamantis argues that fundamental changes in a corporation's character can undermine the rationale for punishing it. If a criminal corporation undergoes an organizational transformation that eliminates its ‘criminal essence’, or the features that led it to behave criminally, then it is essentially a new corporation.Footnote 66 He suggests that the ‘criminal essence theory’ applies similarly to individuals, and that it helps to justify statutes of limitations: ‘as time passes without re-offense, it becomes increasingly likely that an individual who committed a past crime has relevantly different motivations and attitudes, i.e. is a now “different person”’.Footnote 67 The same argument could be made for states. The contemporary United States might be exempt from punishment for slavery (if not from liability for reparations) because it is fundamentally different in character from the slavery-era United States. It could be argued that the Union purged its criminal essence by fighting the Civil War, or by passing the Civil Rights Act in 1964, or by implementing affirmative action.

However, some criminal essences are much more durable than others, and some may be almost impossible to purge. If a man stole a bike in his youth, but he has not stolen anything for 50 years, then it is plausible to conclude that he has shed his criminal essence. But if he had run a concentration camp in his youth, then it is far from clear that 50 years of good behaviour can erase his criminal essence. Orchestrating a genocide leaves a much more permanent mark on the character of a person than does stealing a bike. This is perhaps why Germany continues to prosecute Nazis long after the fact, and why the most serious international crimes are not subject to a statute of limitations. Similarly, slavery has left a mark on the character of the United States that is not easily erased by institutional reforms or the passage of time. As many would be quick to point out, America's ‘change of heart’ is easy to overstate: slavery gave way to Jim Crow laws and segregation, and the legacy of slavery lives on in the form of racism and mass incarceration.Footnote 68 The criminal essence theory leaves plenty of room for historical punishment, because the criminal essences of slavery and genocide are deep and long-lasting.

The legal principle of nullum crimen, nulla poena sine lege – no crime, no penalty without a (prior) law – provides a more plausible justification for placing a time-limit on the punishment of states.Footnote 69 An agent cannot be punished retroactively for an act that was not a crime when it was performed. This principle is central to the rule of law and is codified in several human rights treaties.Footnote 70 Although enslavement is now a ‘crime against humanity’,Footnote 71 the present-day United States could claim immunity from punishment on the ground that slavery was abolished in the United States long before slavery became an international crime. The principle of nullum crimen thus seems to allow proponents of state crime to avoid the conclusion that states should be punished for historical crimes.

But the limit set by nullum crimen is weaker than it seems. An act need not be specifically prohibited by a statute or treaty in order to be criminal; the act need only be prohibited by customary international law. For instance, as Christian Tomuschat argues, the Nuremberg Tribunal's prosecution of ‘crimes against humanity’ did not violate nullum crimen because the actions that constituted these crimes were already illegal: ‘crimes against humanity could be conceived of as an amalgamation of the core substance of criminal law to be encountered in the criminal codes of all “civilized” nations’.Footnote 72 Similarly, punishing states for historical crimes would not violate nullum crimen as long as the acts in question were illegal under customary law at the time they were committed. Slavery was probably illegal under customary international law even in the 19th century, and, even at that time, it was often described as a ‘crime against humanity’.Footnote 73 The rule against retroactive punishment thus does not always rule out punishing present-day states for historical crimes.

One could argue that the United States was not subject to the customary prohibition of slavery because it was a ‘persistent objector’ to that custom. But the persistent objector rule is controversial at best. Compiling many previous criticisms, Patrick Dumberry argues that this rule has weak judicial recognition, is unsupported by state practice, and is logically incoherent.Footnote 74 He also shows that the very idea of the persistent objector is fairly new: ‘Although the concept of persistent objector can be traced back to more than 50 years ago, it only truly emerged as a coherent theory some 20 years ago when it was embraced by the United States’.Footnote 75 If the customary prohibition of slavery preceded the persistent objector rule, then it is hard to see how that rule could exempt the United States from that custom. Moreover, the persistent objector rule does not apply to peremptory norms, or jus cogens.Footnote 76 In any case, American slavery is only one among many examples of historical crime, most of which do not raise the issue of persistent objection. Should Turkey be punished for the Armenian Genocide?Footnote 77 Should Italy be punished for aggression against Ethiopia in the 1930s? Should Belgium be punished for atrocities committed in the Congo Free State?

The Temporal Problem is troublesome even for more recent state crimes. Consider the 1968 Mai Lai Massacre, in which American soldiers killed hundreds of unarmed Vietnamese civilians. The Massacre was not just an act of a few rogue soldiers; it could plausibly be described as an act of the United States.Footnote 78 Should the United States still be punished for this crime? Few people would think so, even if they did think the United States should still apologize or pay reparations. But the argument for state crime leads almost inescapably to the conclusion that the United States should still be punished. The passage of a few decades surely does not absolve an agent of responsibility for war crimes. If the individual moral agents who perpetrated or orchestrated the massacre should still be punished, then it is hard to see why the relevant corporate moral agents should be granted impunity.

Proponents of state crime could deal with the Temporal Problem in one of two ways. First, they could bite the bullet and accept the implication that states should be punished for historical crimes. This would require an argument that explains why the common intuition against historical punishment is mistaken. Second, proponents of state crime could argue for a time-limit on the prosecution and punishment of states. As I have shown, this argument would not be easy to make. The obvious justifications for a time-limit, such as changes of character and nullum crimen, are not of much help. In addition, any argument for a statute of limitations on state crimes would have to be reconciled with the fact that serious international crimes committed by individuals – many of which also constitute state crimes – are not subject to a statute of limitations.

One way to blunt the force of the Temporal Problem is to admit the force of the Agency Problem. If, as I have argued, dictatorships and simple oligarchies do not meet the conditions for corporate agency, then many historical crimes are not attributable to states in the first place. Criminal responsibility for Belgium's atrocities in the Congo would have died with Leopold II (though, again, reparative responsibility might live on). The fact that there were more dictatorships and simple oligarchies in the past mitigates the Temporal Problem. But this fact also restricts the scope of state crime in the present.

State responsibility without criminal responsibility

So far, I have argued that holding states criminally responsible is fraught with conceptual and practical difficulties. In this section, I argue that abandoning the idea of state crime would be no great loss. All of the important functions of responsibility can be served by a reparative system of state responsibility in conjunction with criminal trials of individuals.

One formidable argument for reviving punitive conceptions of state responsibility is that their decline in the 20th century has hollowed out the moral vocabulary of international law. As Gabriella Blum argues, the moral language of punishment has been replaced by the language of ‘value-neutral “prevention”’; ‘what is lost by a reliance on a preventive paradigm’ is ‘the moral evaluation of state conduct’.Footnote 79 Similarly, Lang argues that liberal internationalism has replaced ‘punitive action’ against states with ‘strategic action’.Footnote 80 The result is that sanctions and interventions can no longer be justified in moral terms as means of punishing criminal states. Instead, they can be justified only in strategic terms as means of preventing or neutralizing threats.

Blum argues that the shift from punishment to prevention is not as progressive as it seems. Although ‘prevention may sound like a less oppressive policy than punishment, it may in fact be far less constrained and more ruthless’.Footnote 81 Whereas punishment requires due process and proportionality, prevention does not. In addition, ‘a punitive framework is generally more restrictive in what it allows by way of sanctions in anticipation of crimes’.Footnote 82 Preemptive wars are much easier to justify as ‘strategic action’ than as ‘punitive action’, since punishment is inherently backward-looking.

It is undoubtedly true that prevention can be less constrained and more ruthless than punishment. It is also true that state responsibility requires a moral vocabulary. But the choice we face is not just between the moral vocabulary of punishment and the strategic vocabulary of threat-prevention. There is an alternative moral vocabulary of reparation, which is the vocabulary that the International Law Commission's Articles on State Responsibility already uses.

Article 31

Reparation

(1) The responsible State is under an obligation to make full reparation for the injury caused by the internationally wrongful act.

(2) Injury includes any damage, whether material or moral, caused by the internationally wrongful act of a State.Footnote 83

Abandoning the concept of state crime does not leave international law in the moral vacuum of prevention, because state responsibility can instead be understood in reparative terms.

The literature on reparations and transitional justice identifies a broad range of possible responses to atrocity: (1) acknowledgment of wrongdoing, as in an official apology or a truth commission; (2) punishment of the perpetrators; (3) compensation of the victims; (4) lustration, or removal of officials who were complicit in the wrongdoing; (5) rehabilitation of the perpetrators; and (6) reconciliation, which usually involves some combination of the above.Footnote 84 Each of these responses can take individualistic or corporate forms. Acknowledgment can take the form of individual apologies or of state-sanctioned recognition of the wrongdoing. Compensation can be paid by individual wrongdoers or by the state. Lustration can apply to particular individuals or to all members of a party or regime. Punishment can target particular individuals or the state as a whole. Rehabilitation can aim to change the attitudes of particular wrongdoers or to reform institutions. Reconciliation can aim to reconcile the victims with their neighbours or with the state itself.

This typology of responses to atrocity is rough and non-comprehensive, and the distinction between individual and corporate responses is not always so clear in practice. For my purposes, there are two important points. The first is that punishing the state is only one of many possible responses to atrocity. The second point is that, of all of these responses, punishing the state is the only one that requires the concept of state crime. Acknowledgment, compensation, lustration, rehabilitation, and reconciliation can all be justified in purely reparative terms. Abandoning state punishment would still leave a rich and varied set of options.

One could argue that some of these ‘reparative’ responses to atrocity are punishments in disguise. As I have previously acknowledged, reform and reparations can become implicitly punitive (according to Wringe's expressive theory) when they inflict harsh treatment on citizens. But reparative measures are not necessarily punitive because they are not necessarily harsh or expressive. Lustration may be harsh, but it need not be expressive; the targeted officials need not be publicly named, blamed, or shamed. Public apologies are expressive, but they need not be harsh; to repent is not necessarily to suffer. Compensation will almost always be expressive,Footnote 85 but it need not be harsh. If compensation payments are small relative to the size of the state's budget, then no one will suffer from them. Rehabilitative measures need not be expressive – states could be ‘nudged’ to change their behaviour or institutions – and they can be beneficial (as in some post-war reconstruction projects). When supposedly reparative measures start to become punitive, that is a sign that they have gone awry.

It may be that punitive responses to serious international crimes are necessary, either to express condemnation or to provide an outlet for retributive impulses. Lang argues that punishment is essential for a just international order.Footnote 86 But it does not follow that states must be subject to punishment. An outlet for punishment can already be found in criminal trials of individuals. However, proponents of state crime might reply that punishing individuals is not an adequate substitute for punishing the state. Since the state is a distinct agent, its criminality is not reducible to the criminality of its members. As Lang argues, individual criminality and state criminality are conceptually distinct: ‘crimes can be attributed to states without attributing them to individuals’.Footnote 87 And when a state commits a crime, the state itself should be punished.

It is generally true that individual forms of responsibility are not adequate substitutes for collective forms of responsibility. This is one of the key insights from the literature on corporate responsibility.Footnote 88 As Anna Stilz argues, holding only individuals responsible for corporate wrongdoing can result in a ‘shortfall’ of responsibility, since the ‘total harm’ can be ‘more than the sum of the employees’ intentional contributions'.

On 28 November 1979, a flight operated by Air New Zealand crashed directly into the side of Mount Erebus, a 12,000 foot volcano, killing all 257 people aboard. An inquiry determined that the primary cause of the crash was an inadequate company organization that led to the filing of a faulty computer flight plan. In this case, various employees' actions combined to create a disaster that no one employee could have reasonably foreseen. While several people did contribute to the crash, in isolation their separate actions seemed unlikely to lead to any disaster.Footnote 89

The families of the victims would be undercompensated if they could seek compensation only from particular individuals. Not only do the vast majority of employees have good excuses; it is also very difficult to determine which individuals contributed to the outcome, and to what extent. Holding the corporation liable is therefore necessary to make up the shortfall.

Holding individuals responsible for atrocities committed by states would often leave similar shortfalls. Although some compensation can be extracted from individuals, it will rarely be possible to extract enough. The individual perpetrators may be deceased, unable to pay, or simply impossible to identify. States, on the other hand, have long lifespans and deep pockets. Responsibility shortfalls need not be purely financial; there can also be shortfalls in acknowledgment or rehabilitation. Although apologies from individuals might give the victims or their families some satisfaction, they do not carry the same weight as an official apology from the state.Footnote 90 And although it might sometimes be possible to rehabilitate individual perpetrators en masse, as Rwanda has tried to do, it may also be necessary to reform the structure of the state. The purpose of holding states responsible is thus to make up for these shortfalls.

Proponents of state crime might argue that punishing individuals for states' atrocities leaves a ‘punishment shortfall’, since the criminality of the state is not reducible to or exhausted by the criminality of its members. However, the desire to punish states actually appears to be parasitic on the desire to punish guilty individuals. If, as Lang argues, the criminality of the state were independent of the criminality of individuals, then the desire to punish a state should be unaffected by generational turnovers in its membership or by changes in its government. But the desire to punish a state tends to wane when the wrongdoers have died or left office. No one seriously proposes that Turkey should be punished for the Armenian Genocide or that the United States should be punished for slavery – or even for the Mai Lai Massacre.

Consider the asymmetry between reparations and punishment. Demands for reparations from states tend to persist long after the deaths of the individual wrongdoers, which demonstrates that these demands are genuinely ‘corporate’. Demands for punishment of states tend to perish with the guilty individuals, which suggests that these demands are merely quasi-corporate or pseudo-corporate. The fact that there are no demands for historical punishment alongside historical reparations suggests that punishing states is not a response to a shortfall; it is a shortcut to punishing guilty individuals en masse.

If the desire to punish states is parasitic on the desire to punish guilty individuals, then criminal trials of individuals should be an adequate outlet for punishment after all. As it stands, there is a ‘division of labour’ in international law between individual responsibility (which is punitive) and state responsibility (which is reparative). International law holds individuals responsible in order to exact retribution and to deter future crimes – in particular, where domestic law is absent or ineffective. The International Criminal Court is designed ‘to put an end to impunity’ for ‘the most serious crimes’ and ‘thus to contribute to the prevention of such crimes’.Footnote 91 The role of state responsibility, on the other hand, is to repair harms and compensate victims. The International Law Commission's Articles on State Responsibility focus on the ‘twin obligations of cessation and reparation’, and ‘the burdens that are imposed on delinquent states are exclusively reparative rather than penal in character’.Footnote 92 Whereas individual responsibility is exclusively criminal, state responsibility is more like civil liability.

The division of labour between international criminal law and state responsibility was not a product of deliberate institutional design: ‘the parallel developments of the state responsibility and individual criminal responsibility regimes have occurred in relative isolation from each other’.Footnote 93 While the law of state responsibility developed out of reparations law, international criminal law grew out of post-war trials.Footnote 94 There was no grand design in the background, but there might as well have been. The two forms of international responsibility are complementary: one serves reparative functions, while the other serves punitive functions. There is no need to ‘criminalize’ state responsibility, just as there is no need to ‘civilize’ individual responsibility. Although the two forms of international responsibility may look incomplete in isolation, they fit together to form a coherent system.

Conclusion

I have argued that the idea of corporate crime cannot simply be mapped onto the state. The international order lacks a regulatory framework, akin to corporate law, that ensures that states actually meet the conditions for corporate agency. In addition, the idea of state crime raises the difficult question of how far back historical crimes should be prosecuted. In any case, abandoning the idea of state crime would be no great loss. Most responses to atrocity can be justified in reparative terms, and criminal trials of individuals already provide an adequate outlet for punishment.

This paper makes three main contributions. First, it presents the strongest and most up-to-date case for the concept of state crime. I have collected and synthesized several lines of argument across political theory, IR, philosophy, and law that lend force to the idea of holding states criminally responsible. Although the purpose of constructing this ‘steel man’ was to find flaws in it, it could also be adapted and developed by those who wish to strengthen it.

The second contribution – almost the opposite of the first – is to develop two new critiques of state crime. Previous critics focus on the problems of corporate intent and punishment, which are general problems with collective criminality. Instead, I focus on the problems of agency and time, which are more specific to the state and to international relations. I thus show that the debate about criminalizing state responsibility is more than a rerun of the general philosophical debate about corporate criminal responsibility. The viability of state crime depends not only on issues of social ontology, but also on the structure of the international order and the characteristics of its institutions. Refocusing the debate on structures and institutions will, I hope, help to reinvigorate it.

The third contribution of the paper is to provide a positive vision for state responsibility without criminal responsibility. Oddly, critics of criminalizing state responsibility have not developed a principled alternative. One of the reasons that holding states criminally responsible is so appealing is that, as it stands, state responsibility appears to be normatively impoverished – it is merely ‘non-criminal’. The reparative conception of state responsibility that I have developed helps to fill the moral vacuum left by the decline of punitive conceptions of state responsibility. It also explains how state responsibility and international criminal law fit together. While criminal trials of individuals provide an outlet for punishment, the primary functions of state responsibility are to compensate the victims of large-scale wrongs and to rehabilitate aggressive states.

Acknowledgements

The earliest version of this paper was presented at the 2019 Annual Convention of the International Studies Association, where Rory Cox and Cian O'Driscoll provided helpful feedback. Four anonymous reviewers provided exceptionally extensive comments that greatly improved the paper. I am especially grateful to Adam Lerner for his comments on a previous draft.