This article explores the relationships between young European women who worked in the growing entertainment market in Argentine and Brazilian cities, and the many people who from time to time came under suspicion of exploiting them for prostitution.Footnote 1 I have paid particular attention to the labour arrangements that made it possible for such women to travel by the same regional immigration routes used by many other groups of European workers looking for a better life in South American cities in the early twentieth century. The international travels of young women with contracts to sing or dance in music halls, theatres, and cabarets provide a unique opportunity to reflect on some of the practices of labour intermediation. As their escorts came to be suspected of establishing improper relations with them, the moral dimensions of labour arrangements become visible and allow us a more general reflection on issues that might have been at stake for other groups of immigrant workers.

The article begins with a description of the labour market in the variety branch of show business about the time of World War I, especially in light of the widespread fashion for “white slavery” stories. Such descriptions raise some of the most commonly recurrent images and social meanings attached to the work relations involving women artists in the entertainment market. Work arrangements and women's strategies, though, are not as evident in theatrical accounts as they are in police records of the expulsion of foreigners accused of procuring. In such documents we are reminded of two classic topics in theatre stories at the beginning of the century – those of the mothers of young women artists, and the seducers of chorus girls.

The mercenary spirit of the matrons, at once concerned with the quality of their daughters’ contracts and with ensuring their moral protection by appointing appropriate chaperones, was ridiculed throughout the period in the theatrical press. A mother's greatest enemy was the seducer, a young penniless man who regarded every woman in the entertainment business as sexually available.Footnote 2 In police records of expulsions, male escorts and parents appear as being suspected of profiting from the prostitution of women artists, thus lending new meanings to such stereotypes. Their stories, as described in police records, reveal much about labour intermediation practices and what they meant for contemporaries.

Whether as suspected prostitutes or as artists of a “lesser genre”, as variety was considered at about the time of World War I, the lives of young women artists have not often been the subject of labour history, which has focused rather on other groups of workers and political activists (especially anarchists) travelling along similar routes in the same years.Footnote 3 Variety itself does not have an important place in national theatrical accounts, except as a distant background for performers who subsequently became famous actresses or singers. Nevertheless, variety performances were highly appealing to contemporary audiences, and the travels of variety artists had an important role in creating cultural circuits which eventually elevated some genres and particular dances to the level of “national styles”, as was the case with the tango in Argentina or the samba in Brazil.Footnote 4

Looking at such women through the lens of labour history, and restating their importance for their contemporaries as entertainers, becomes a strategy to enable us to examine their ambiguous identities and the complex relationships they established with those who mediated their work. We can reflect upon how contemporaries perceived the degrees of autonomy and the moral boundaries in the work relations of women artists, or, in other words, fragments of these women's lives, their work arrangements, and their affective relationships with either family or male escorts can be used to shed light on the various connections between work and sexual morality in some South American cities in the early twentieth century.

The specifics of women artists’ work experience, especially the nomadic character of the work and the fact that their activities were hardly easy to classify, make it very difficult to find traces of their lives in the written sources of the entertainment business at the time. One important exception is the records of the Brazilian police, which enforced the Foreigners Expulsion Act of 1907. Police investigations carried out between 1907 and 1920 to secure the expulsion of a wide variety of foreigners viewed as “undesirable” – among them those suspected of procuring – recorded the different experiences of men and women who were suspected of being involved in the sex trade. Among those cases, a few refer directly to women who worked in the entertainment business.Footnote 5

The four cases of expulsion analysed here are therefore part of a larger universe. Although few in number, they attest uniquely to the valuable aspects of women artists’ work arrangements and affective experience. These were women who attracted police attention because it seemed that either their escorts or their relatives were exploiting them, and that allows us to discuss the affective dimension as an inseparable aspect of women artists’ general work experience. Beyond the actual accusations, police records shed light on the expectations and work arrangements that made it possible for young women to travel overseas. They also record the unexpected uses of repressive legislation, such as the Foreigners Expulsion Act, by individuals who were themselves the obvious targets of the law. Finally, they suggest that variety artists’ international travels were a key element of their work experience.

TRAFFICKING AND THE SOUTH AMERICAN ENTERTAINMENT BUSINESS

The dismissal of women performers’ lives by labour and theatrical histories can be partially explained by another specific cluster of contemporary meanings attached to their activities – those which associated them with narratives of the “white slave traffic” so widely publicized on Atlantic immigration routes at the time. Young singers and dancers were recurrently portrayed as victims of mysterious organizations which specialized in deceiving young European women with promises of marriage, employment, or, less specifically, an exciting artistic life overseas in order to force them into prostitution in distant lands. The famous tango composer and theatre writer, Enrique Cadícamo, resorts to this cliché in his memoirs, originally published in 1983. As a major participant in the musical and theatrical scene that flourished in turn-of-the-century Buenos Aires, Cadícamo revealed some inside information on one of the most famous variety theatres of the time, the Casino:

The source of the following information does not come from police records but from what I learned from other tango musicians, now dead […]. By 1918 […] there was in Buenos Aires an obscure underworld criminal organization with headquarters in Marseille, that appeared to be a peaceful international theatrical agency for Latin America. But it was in fact none other than an agency to promote the white slave trade. This organization covered Rio de Janeiro, Chile, and Buenos Aires. Its affiliate in Buenos Aires provided seemingly artistic personnel, such as café-concert singers, pseudo-dancers [sic], chorus girls, thus concealing their real work as prostitutes, and mixing this human traffic with companies of famous wrestlers […] for the historic Greek-Roman wrestling tournaments featured in the Casino theatre on Maipú Street. This was a way to covertly smuggle women into Buenos Aires.Footnote 6

Cadícamo's statement that the famous Casino theatre on Maipú Street was nothing but a pretext for the sexual exploitation of European women was based on what he had heard from old tango musicians whom he had known in his youth. At the time he wrote that, Cadícamo was considered one of the most important composers of the twentieth century, and a living first-hand witnesses to the bohemian life of 1920s Buenos Aires. His music became popular in the 1920s; later he published poems too, as well as fiction and non-fiction accounts that eventually became an invaluable source for the history of tango and the tango scene, about the theatres, music halls, cabarets, and café concerts at the turn of the century.

The French origin of the “white slavery” organization and its network in South American capitals echoed in part the renowned image of Buenos Aires as an important site of the international traffic in women. Received wisdom stated that white slave traffic was handled by mafia-type organizations, mainly Jewish, although they might include other nationalities, whose actions were never made totally clear.Footnote 7 In this particular text, in contrast to other passages in his writings and other testimonies, young women's overseas trips as well as their contracts are portrayed as a front, and the busy artistic scene at the Casino in the 1910s becomes a cover for the exploitation of young European prostitutes.Footnote 8

Cadícamo's account touched upon elements that surely resonated among Buenos Aires readers and that was in turn immersed in a long tradition of “white slave traffic” stories. From 1870, stories of “white slaves” increasingly involved South American cities, especially Buenos Aires, as European immigration to that part of the world grew to unprecedented proportions. As many authors have pointed out, such stories usually expressed anxieties related to immigration and female work in terms of sexual morality. That was true for Buenos Aires and also for those Brazilian cities that received a large number of immigrants, such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.Footnote 9

Apart from the common plots shared by white slavery stories (in Buenos Aires, São Paulo, and Rio), each city featured local details related to specific social and political contexts. In Buenos Aires, stories expressed mainly the local tensions triggered by the unwelcome side effects of European immigration, which had completely transformed the city and the country in just a few years. They also justified heavy-handed state intervention in the organization of the sex trade, through regulations issued from 1875 to 1936.Footnote 10 In Brazil, similar stories had a different effect as they became widespread alongside public debates on the abolition of actual slavery and the future of labour relations. The gender and racial connotations of the vocabulary inspired by the struggle against black slavery, then coming to be used to refer to the international sex trade, was particularly disquieting for the Brazilian authorities. The social and political conflicts triggered by the increasing state intervention through progressive regulation to abolish general slave labour lent a negative image to the state's potential intervention to regulate another trade that was also viewed as immoral. The situation affected the policy for control of the sex trade, which in Rio de Janeiro was left mainly to the police, resulting in a non-regulating trend which persisted in the Republic after 1889.Footnote 11

If the local uses and meanings were different in Argentina and Brazil, the vocabulary borrowed from slavery to talk about the sexual exploitation of European women had similar connotations in many places. In fact, it was associated not only with a state of backwardness, violence, coercion, and immorality, it also legitimized the public intervention on moral grounds of specific social sectors and organizations, on behalf of the victims. From that perspective, during the years following World War I the League of Nations became a key authority on the subject. The investigations carried out by their Body of Experts in search of the “true” dimensions of human trafficking attest to the importance attributed to the international circulation of women and the anxiety that triggered in many Western countries. Among other things, the interventions by the League of Nations helped consolidate and generalize the causal association between regulation of prostitution and traffic in women. The underlying idea was that in countries where prostitution was regulated, it eventually facilitated the action of procurers and traffic in women flourished. Thus, in the 1920s, the widespread international discrediting of regulated prostitution reinforced the idea that Buenos Aires was a paradise for traffickers, which in turn created a problem for the Argentine authorities.

As a result of such investigations, in 1927 the League of Nations published an experts’ report on traffic in women and children.Footnote 12 The report shows on what terms and to what extent a large proportion of the international travel experienced by women in pursuit of work contracts and promises of marriage became a matter of real concern to national governments. Stories of trafficking developed a plot that expressed the apprehension triggered by the unprotected international circulation of vulnerable individuals, as women and children were seen to be. Obsessed with determining the real contours of the “white slave trade”, the League of Nations observers were mesmerized by various modalities of young women's international travels.

Among the diverse offers of employment and promises of marriage, the experts focused particularly on the modus operandi of an increasingly international entertainment market. The experts’ findings reveal how a fear for women travelling alone or “in bad company” exposed a wide suspicion of different work experiences and of intermediaries as being part of the sex trade. By following the steps of many young women who crossed national borders, investigators were able to isolate specific and recurrent cases of what they saw as traffic in women in every European country, as well as in Central and South America – girls engaged as members of troupes to perform in “music-halls, cabarets, cafés, and other amusement venues”.Footnote 13

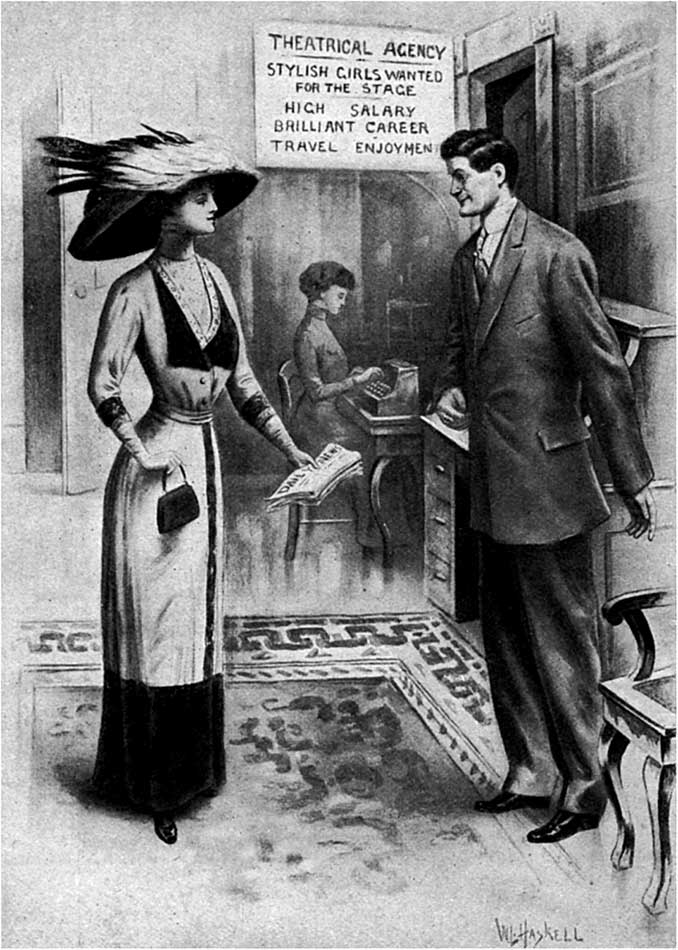

Figure 1 When he edited Fighting the Traffic in Young Girls,14 the Methodist missionary Ernest Albert Bell publicized the basic lines of his anti-vice crusade as the Secretary of the Illinois Vigilance Association. Illustrations were an important part of the propaganda. The illustration above refers to what the book presented as one of the most successful methods used by traffickers to “lure” young innocent women. Disguised as a theatrical agent or manager, the trafficker promised a factory girl a better life “upon the stage”. In the background is the list of what would appeal to a “girl's ambition”: promises of a “high salary”, “a brilliant career”, and “travel enjoyment”. When, almost two decades later, the Body of Experts of the League of Nations relied on similar accounts, such stories were already widespread throughout the circuits of international labor immigration. Unnamed artist in Bell, Fighting the Traffic in Young Girls, Mary Evans Picture Library. Used with permission.

Contemporary observers, who regarded themselves as unbiased, believed that not all travelling companies acted as a disguise for prostitution. For those observers, “some of the troupes are under proper management and supervision, but instances were brought to our notice of deliberate exploitation”. But how is one to establish the difference between one and the other? For Cadícamo, talking about it in the 1980s in reference to the Casino theatre, sexual exploitation was undoubtedly the real motive, despite all appearances to the contrary. In 1927, the League of Nations experts were more sensitive to the nuances, as they focused on a variety of situations and work arrangements that were being carried on right in front of their eyes. They noted the centrality of contracts for the cases under scrutiny:

The contracts which these girls sign often conceal the actual conditions and there is nothing to arouse the suspicions of the girls who sign them. In other cases the terms of the contract are so unfair as to place the girls entirely at the mercy of her employer. An investigator secured a copy of a contract made between the proprietor of a music hall and a dancer aged 18. Under this contract she was liable to be transferred at will; she could be discharged for a variety of reasons over which she had no control, such as “indisposition, loss of voice, disease or suspension of work for any reason whatsoever”. The hours of work were unlimited and the small salary (5 francs a day) was subject to capricious fines for not obeying rules that are unknown until they are posted on a notice board. The inhumanity of such contract is almost bound to produce disaster in the case of the foreign girl alone in a strange town and without a friend to turn to when summarily dismissed.Footnote 15

Observers were struck by the harshness of that labour market. Descriptions of terrible work conditions, low wages, and of young ages, stressed the women's extreme vulnerability, only worsened by the isolation that resulted from all the travelling required in their trade, and by the brevity of their employment. In that context, the observers saw prostitution as a permanent and almost unavoidable risk. For them, work contracts were proof of immoral exploitation because of the unfair conditions, while at the same time the contract itself was a veil to hide the very exploitation it implied, since the contracts were presented as arrangements between two free parties.

Although to some degree both accounts are similar, in Cadícamo's view there was no possibility of doubt: the organization which owned the Casino theatre in Buenos Aires was simply a criminal gang; the theatre was nothing but a front for the traffic in women. However, the League of Nations observers suggested instead that the situation could be much more ambiguous, as they situated the problem in the nuances of work conditions. Despite such significant differences, both accounts formulate the problem in the same terms – as if it were possible to draw a clear line between proper and improper ways of hiring young women in the entertainment business. Moreover, both views preclude the possibility of posing different questions: first, questions about degrees of autonomy, violence, and exploitation in the artists’ work contracts. And, second, about how those degrees were negotiated by the parties involved, especially by the travelling young women whose social experiences shaped morally ambiguous identities as artists, prostitutes, and hired workers.

WORK CONDITIONS IN SECOND-RATE THEATRES AND CAFÉ CANTANTES

In the early twentieth century, theatres in Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo featuring Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, and a few local companies competed with a variety of café concerts, circus rings, and improvised stages to attract audiences eager for entertainment. Cabarets would be added in the 1910s, and although with local features, the café-concert model or variety theatre was replicated in many Argentine and Brazilian cities, thus shaping a route for touring artists. Although the performances associated with such venues were considered a minor genre, boundaries between styles and between artists were not always clearly definable, despite the efforts of classical accounts of theatrical history to depict a linear evolution culminating in a national theatre.Footnote 16 From that perspective, recurrent moral suspicion of women artists – especially from the police – speaks of a wider concern about the impossibility of defining fixed and stable identities for such women.Footnote 17 There were significant elements in the organization of the entertainment labour market that prompted the League of Nations observers and Cadícamo to view work relations in the entertainment business as a site for potential sexual exploitation.

In the early years of the century, variety was an expanding theatrical activity. Announcements of new and refurbished show-business establishments in Brazilian and Argentine cities attest to that. News items portrayed theatre owners as risk-taking entrepreneurs and published full-page advertisements of their programmes in the most important magazines of Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro. The business involved a broad range of people who sometimes performed multiple functions – as managers, directors, art directors, theatrical agents, and intermediary agencies – as well as a number of additional activities, such as selling drinks and showing silent films in the intervals of stage performances. Entrepreneurs catered to diverse audiences, who expected to have fun, with circus-like attractions, such as wild animals, acrobats, Roman wrestlers, female impersonators, illusionists, and singing and dancing girls.Footnote 18

Performers used names designed to associate them with the “typical” styles of specific regions. Argentine stages featured artists such as “La Argentinita” (although she was actually Spanish), “La Malagueñita”, and “La Sevillita”.Footnote 19 In Brazilian cities, a magazine dedicated to the entertainment business published advertisements for similar artists announcing their availability for employment. If Spanish singers were all over Buenos Aires, there was a “Bella Diana, Portuguese singer and fado performer” in Rio de Janeiro, but also “La Cubanita, Spanish singer”. Some names suggest erotic performances, such as “Martha Cotty, French eccentric”, or a combination of genres, including “La Cholita, Spanish singer and suggestive poses”. Although some artists were clearly associated with specific performances, such as lyrical singers and classical ballet dancers, somewhat incoherent names and descriptions were abundant. It is hard to imagine what kinds of act were performed by the “Hispanic-French singer René D'Arcy”, or the “Hispanic-Brazilian singer called Egyptian Estrellita”.Footnote 20

The combination of references to places of origin with elegant, exotic, or “typically regional” styles ultimately reveals how far such theatrical images were carefully constructed, as well as underlining the appeal of an “international” identity with exotic but civilized connotations. It was all very similar to a movement taking place simultaneously in the characterization of foreign prostitutes either as “Frenchwomen”, which carried promises of civilizing the local men in elegant and sophisticated sexual relations (and manners), or as “Polish women”, which associated them with a degraded sort of exoticism. Rather than designating actual nationalities, the characterization seems to have mirrored local imagination and the interest in consuming foreign – specifically French – products and lifestyles.Footnote 21 Sometimes then, reference to the “French” origin of a singer or dancer suggests an intentional play upon the sexual connotation of such identities.

Women artists embodied complex intersections between the new consumer trends (including sex), social status, and nationality. They applied their talents in theatres and similar venues that offered a wide variety of entertainment. In Rio de Janeiro, the most important entrepreneur employing women artists at the turn of the century was the Italian Paschoal Segreto.Footnote 22 Since the early 1900s he had been investing in a wide array of entertainment houses, next to bars, restaurants, brothels, café concerts, and improvised music halls that featured shows or films and which functioned as beer parlours. One of his establishments was the Maison Moderne, dedicated to variety shows. Despite the connotations of elegance in the French name, the Maison Moderne was described by an observer as a mixture of fair and theme park, offering “target shooting, a Ferris wheel, and a carousel”, which most probably attracted families to its daytime shows. However, at the back there was a small stage featuring evening shows for an adult audience.Footnote 23 As early as 1901, advertisements revealed that managers were interested in publicizing their investment in modern furnishings and renewed international attractions.Footnote 24 Expanding his investments, Segreto also became the owner of São Paulo's Casino theatre in the 1910s.Footnote 25

Meanwhile, in Buenos Aires too, the most important variety theatre was named the Casino. One of the owners of that Casino was Carlos Seguín, who later sold it to a limited liability company with English capital wishing to expand into Uruguay, Chile, and Brazil. Under the suggestive name of “South American Tour”, the company employed variety artists for the Casino and the Scala in Buenos Aires.Footnote 26 Some years later, a contemporary recalled “the admirable companies that Seguín brought to the Casino”, attesting to its popularity in the pre-war years.Footnote 27

By the time specialized intermediary agencies appeared in that setting, by the end of the 1910s, Argentina and Brazil had already shared cultural circuits for a long time.Footnote 28 Their visibility was certainly related to the ways in which World War I affected such routes, when communications between Europe and the Americas were interrupted. During those years, South American tours brought North American attractions to the Casino theatre in Buenos Aires.

At the same time, in Rio de Janeiro, the theatrical agency Kosmopol published the magazine Arte e Artistas [Art and Artists]. Defined as an “intermediary press between show business managers and variety artists”, it worked as an “Artists Guide”, available to managers eager to engage new attractions. The agency requested performers (who were probably already stuck in South America) to send “photos, conditions, and exact information about their availability”, and took responsibility for the fulfilment of their contracts. By October 1921 it announced the opening of a music and dance academy for cabaret artists to improve their craft.Footnote 29 The publication allegedly circulated in “Brazil, Argentina, and Europe”, although its headquarters were in Rio de Janeiro. Although no more than four numbers were issued, its brief existence attests to the increasing circulation of capital invested in the dynamic world of variety theatre. It also maps the regional artistic route that interested artists, business managers, and audiences. As it was, either with or without that kind of structured intermediation, managers of small theatres and café cantantes and the artists they needed found ways to meet each other.

A growing number of travelling artists, who could perform “typical” styles and who were willing to tour different cities, became a crucial part of the South American entertainment market at the beginning of the twentieth century. The blurred borders between artistic styles, flexible artistic identities, and constant travelling were reinforced by another feature of that world – the expectation of becoming rich and famous very quickly, a topic that appeared repeatedly in plays featuring ingenuous local artists on both sides of the Atlantic who dreamed of success overseas.Footnote 30

For instance, the success story of Italian actress Amelia Lopiccolo on the Brazilian stage, as told in a traditional history of Brazilian theatre, can be read as a tale of social mobility.Footnote 31 It begins like the story of many other European girls who had travelled to South America by the end of the nineteenth century. First she crossed the Atlantic with a group of variety performers on tour to a famously picaresque café cantante in Buenos Aires, El Pasatiempo. Later she performed at Eldorado, a similar café in Rio de Janeiro. However, quite suddenly everything changed when Jacinto Heller, the manager of the Santana theatre, witnessed her gracious singing and her “fascinating, darting eyes”. According to that account, Heller “rescued” her from the café cantante and gave her the much-coveted position as the star in a renowned theatre company. By impersonating a famous actress of the time, she won her own place on the national stage, moving from Europe to South America, and from the lesser variety genre to mainstream theatre.

Exemplary stories like Amelia Lopiccolo's touch upon the suspicion of prostitution and the difficult working conditions for female artists merely as vivid details, irrelevant compared to the denouement that always confirmed the actress's ultimate success. The author of Lopiccolo's story chose a brief but significant tale to illustrate that artists never had a day off, had to perform many times a day, and were vulnerable to breaches of contract when tours failed to turn a profit. In a passing reference, he mentions that when Heller's female artists complained about their working conditions in the Santana theatre, the entrepreneur immediately threatened to replace them with “Frenchwomen”.Footnote 32 Reference to nationality suggests not only a competitive labour market on the supply side and little room for negotiation; it also hints at the sexual availability of hired artists, as the association of Frenchwomen with elegant prostitution indicates.

Amelia Lopiccolo's story, which took place around the 1890s, contrasts with the tale of the Italian Paulista comedian, Nino Nello, from some years later. Recalling his early days in the postwar years, Nello stated that by then the variety genre paid better than the starvation wages of mainstream theatre. He remembered obtaining a contract thanks to the “South American Tour” and performing as an international imitator, not only at the Casino theatre in Buenos Aires, but also “all over Argentina and the Pacific Republics”.Footnote 33 According to Nello, that agency played a key role in “booking artists, with pre-arranged dates, in several entertainment establishments with which they had agreements”.Footnote 34

Accounts of Lopiccolo's and Nello's lives stress that both worked hard and travelled a lot, using all the resources available to them to achieve artistic social mobility. There was a certain amount of strategy and initiative in both careers. There was a significant difference between them, however, and it was not just the period, given that Lopiccolo performed in the late nineteenth century and Nello was active in the 1910s. In Nino Nello's account, the precariousness of work conditions allowed him to develop his talent: as an “international imitator” in other countries, he impersonated all the different “typical types”, playing Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, and even Turkish characters. However, for Lopiccolo and for many other women artists of the period, the goal was to attain a less ambiguous identity by acting within the available roles, hoping eventually to become accepted as a recognized artist and, perhaps, an independent entrepreneur herself.Footnote 35

Goals of upward mobility coexisted with other ways of understanding work in the world of entertainment, and that became evident during the 1919 and 1921 strikes by theatre workers in Buenos Aires. The year 1919 was famous in Buenos Aires for the intensity of social conflicts, workers’ protests, and police repression. In May, even theatre artists organized a strike, which paralysed entertainment halls in the Argentine capital for almost a month.Footnote 36 Foreign and Argentine actors, supported by chorus girls and members of other trades, joined forces to demand, among other things, payment for additional shows and a general wage increase. In the context of the strike, they used the trope of the “theatre family” not to reinforce a hierarchical and unequal organization, but rather to allow different performers – those who worked for wages and those who owned their companies – to unite at least temporarily over a common agenda. Differences still remained though. Some variety performers even sought to form their own organization, the “International Society of Variety Artists”. One of its main demands was that agents should donate a percentage of their earnings to create a mutual aid society.Footnote 37

The meanings of intermediation thus varied. In the context of theatre strikes in Buenos Aires, the role of agents had a negative connotation, and performers acknowledged their presence only to demand that their functions be regulated.Footnote 38 In contrast, Nello's testimony argues that the intermediary agency offered a chance of survival during a time of crisis. From yet another perspective, intermediation played a different role in the matter of contracts with young women. Travelling women artists playing in dubious café concerts and cabarets, who passed as “Frenchwomen” impersonating renowned artists (as did Lopiccolo), or who worked in places where prostitutes, waitresses, and artists all seemed sexually available to customers, shaped narratives that cast doubts on their “real” identities as well as those of their agents. Overall, gender and class tensions came together in more or less explicit ways in all the accounts of work relations in the entertainment business, acquiring different specific meanings.

For many women who were less successful and who travelled in search of profitable contracts, the instability of their identities (as artists or prostitutes) was part and parcel of their business. Stories of “white slavery” expressed their situation particularly well, by erasing their strategies and actions in favour of a victimizing perspective. The particular organization of the work of female entertainers (of men) attracted the attention of police authorities in all the South American countries where women artists performed. Brazilian police would then put pressure on individuals who might be related to them, raising the suspicion that they were profiting from the women's prostitution. Therefore, in many cases, records of the police investigations of procurers, carried out in order to expel them, might be a valuable source for examining the work experience and strategies of women in the variety business.

EXPULSION OF FOREIGNERS LEGISLATION

From the beginning of the twentieth century, the internationalization of the public examination of the trafficking of women evolved, with debates on how local police forces should meet the many threats which were increasing internationally, such as organized crime, but most especially anarchist activists.Footnote 39 The widespread perception of such danger in different countries justified the approval of new legislation intended to develop a common front against international criminals.

The 1902 Residence Act in Argentina and the Brazilian “Gordo” Act of 1907, which regulated the expulsion of foreigners as a prerogative of the executive, probably had a significant effect in the South American context.Footnote 40 The legislation tended to strengthen police powers to the detriment of judicial procedures, so that it became widely denounced as authoritarian and unconstitutional, as it was used to expel the leaders of labour movements. Recent scholarship has also highlighted the use of the same repressive legislation against other groups of foreigners, identified as thieves, vagrants, swindlers, and procurers – virtually anyone who fitted the category of “a threat to national security and public order”.Footnote 41

While the Argentine law extended police powers of discretion to act against any kind of “undesirables” without judicial investigation, the Brazilian Expulsion Act demanded that accusations of “vagrancy, begging, and procuring” be “thoroughly checked”. In the latter case, it meant that to prove procuring charges the police had to gather “undisputed evidence”, or at least “the statement of two undisputed witnesses who could confirm the truth of the fact”.Footnote 42 That meant that, at least in Brazil, police power over the whole procedure was constrained by a body of regulations, similar to police inquiries in the first stages of any judicial investigation. In a context in which both Argentina and Brazil developed specific legal structures to control prostitution and to punish procuring, the unique characteristic of the Brazilian legislation had specific consequences. While in the early twentieth century Argentina followed a French-inspired model of regulation which barely punished the crime of corruption of minors, in its penal code of 1890 Brazil adopted a broad definition of procuring, to include different ways of inducing women to become prostitutes, such as making a profit from offering them varieties of assistance, for example, with housing, or money.Footnote 43

Thus, the Brazilian police had already had experience of trials of that type, which had been carried out as part of police-led campaigns of “moral cleansing”, or when women had lodged complaints against their landlords or landladies, and that experience surely proved useful in collecting evidence for the expulsion of those accused of procuring.Footnote 44 Expulsion procedures and criminal trials for procurement were similar up to a point, although the former were quicker and summary, offering the police a wide range of action. In fact, judicial interference only occurred when a defendant succeeded in obtaining a writ of habeas corpus. Accusations of persecution and police tampering with evidence were very common, but, all the same, the documents resulting from such procedures reveal certain aspects of the relationships established between young women travelling with work contracts to perform in variety and many of the people they met along the way. That, in turn, sheds light on a rich network of work intermediaries. Thanks, then, to repressive police action against foreigners they suspected of procuring offences, we are able to recover part of the transnational experience of women's lives, inasmuch as Brazilian police investigations recorded, if indirectly, the past experience of those women in Buenos Aires and other South American cities.

Police repression against certain foreign groups, triggered by the Expulsion Act, was compounded by an increasing concern with keeping under surveillance those who disembarked at South American ports. With the intensification of eugenic and xenophobic feelings after World War I, many countries passed restrictive legislation on immigration in the 1920s. In the ports of Argentina and Brazil, the new legislation was intended to prevent the entry of sick and elderly people, the disabled, the mentally disturbed, and prostitutes. In previous years, there had already been an increasing demand for passports, criminal records, and certificates of mental health and good conduct. Newer and more sophisticated methods of identification, such as photographic records, were used together with older procedures, which included certificates issued by the local police.Footnote 45

However, the main problem for police authorities remained – how to identify the “undesirable” type in the midst of great groups of immigrants who arrived in Brazilian and Argentine cities. The requirement for more documents still went hand in hand with a discretionary identification procedure based on a first glance, an expectation of visual recognition. Therefore, the experience of a first meeting between police officers and women travelling on their own was crucial in fixing the women's identities. Throughout the years, foreign women travelling alone could always expect problems when boarding or leaving ships. Female performers travelling with work contracts and return tickets soon appeared in briefings to consulates, police reports, and investigations concerned with expelling “undesirable foreigners” on account of trafficking. And those records also travelled to both sides of the Atlantic.Footnote 46 Behind the coexistence of different identification procedures was the presumption that young women were vulnerable to deceit, and the natural victims of sexual exploitation. Therefore, their travelling companions came under police scrutiny. Because of that, expulsion investigations produced a revealing record of work relations.

Figure 2 The illustration on the cover of the Argentine magazine Fray Mocho depicts two ugly women talking about a telegram from London in which the English authorities complain that: “It is nearly impossible for English artists to find respectable lodging in Buenos Aires, and that many women artists hired to perform in Buenos Aires stages are forced to live in dens of corruption.” The joke is the pair's fear of going out in the streets and being mistaken for “English artists”, when there is no chance such a thing could happen. Fray Mocho, 15 July 1914.

LOVERS AND LECHERS

The journey of an Italian singer known by the stage name of Lili Bijou in the Casino theatres of both Buenos Aires and São Paulo in 1911 and 1912 reveals different aspects of work routes in the variety business.Footnote 47 Lili arrived from Italy with a contract to sing in Carlos Seguín's Casino theatre in Buenos Aires. Once the season was over, she left for Montevideo, and then went on to work in São Paulo's Casino, which probably then still belonged to Paschoal Segreto. In São Paulo, she stayed at the “Maison Dorée”, “a regular boarding house for female artists who have contracts in the city”, as stated by its Italian owner. The day she arrived, she met Dr Jorge, an Italian engineer who, having seen her at the Maison Dorée, wished, as he put it, “to offer his protection and take care of her lodging expenses, providing her with enough money to cover all her needs”.

In turn-of-the-century São Paulo, “artists’ boarding houses” were considered to be elegant and sophisticated brothels, patronized by men with enough resources to do what Dr Jorge was doing, which amounted to paying an artist's expenses in exchange for her company for a while. Everything seemed to be going well and most probably Lili's story would never have been recorded anywhere had it not been for the unexpected appearance of a young Italian man, Henrique Resta, who had escorted Lili from Buenos Aires. When Dr Jorge was told that he was “wasting his time and money” because Lili was already with someone else, his first reaction was to pay for Henrique Resta's return ticket to Italy. The young Italian refused the offer and police intervention ensued.

Although the original accusation Henrique Resta faced was of procuring, instead of laying criminal charges the chief of the local police sought a summary solution. He gathered statements from witnesses claiming that Henrique Resta walked by Lili's boarding house every day, and sent her notes. Witnesses said it seemed that Lili and Henrique were not only lovers, but that she was also paying his expenses in São Paulo with the money obtained from the men she entertained at the Maison Dorée. The police chief therefore concluded that Resta was behaving like a gigolo, while he for his part insisted that he was actually a lawyer, and that he had worked for the prestigious newspaper La Patria degli Italiani in Buenos Aires. His family, he said, was sending him money from Italy. However, his claims were to no avail and the brief police investigation resulted in the standard ministerial decree of expulsion.

The only person in São Paulo who seemed to know Henrique Resta well was Lili Bijou. She told the police that they had been together in Italy, but that since her family did not approve of their relationship they had decided to go to Buenos Aires, where she had a contract to sing at the Casino. She backed Resta's explanation that he received money from his family, and so he did not need hers. Her attitude contrasts greatly with other expulsion investigations initiated as the result of explicit accusations of procuring by women against partners or former partners. In Lili's case, it was evident that, whatever the terms of her relationship with Resta, she did not want the police to meddle in it. That might of course have been because she was either in love with him, or too scared.Footnote 48

However, if Lili herself was content in her relationship with Resta, other people were upset by his unforeseen presence. Lili Bijou's arrival in São Paulo had raised many expectations in different men. The manager of the Casino surely expected her to sing in his theatre for the period agreed in the contract. He might have expected her to stay at the same boarding house where the other artists lived. The owner of Maison Dorée might have expected her presence to attract visitors like Dr Jorge, willing to spend money there. As for Dr Jorge, he must have expected Lili to give him her undivided attention in return for the money he was spending on her, so that all those various expectations suggest that the services Lili performed triggered a number of male pastimes that probably included sexual activity, but were not only about that.

Lili Bijou's multiple activities indicate that she relied on all of them, everything from her paid performance at the Casino, accepting Dr Jorge's money, to perhaps even a certain amount of gambling, according to witnesses. It all went to make her tour through Brazilian cities profitable, and she might have reasoned that she could keep all her other endeavours going and continue a probably romantic involvement with the young Italian at the same time. Nevertheless, the four main witnesses at the police station, all of them Italian men apart from a Uruguayan woman who also knew Dr Jorge, described how Henrique Resta prevented Lili from doing her job at the Casino theatre as defined by her contract, although it is likely that the contract did not specify quite all that was expected of her. It is interesting to note that the contract was referred to but never seen in the course of the police investigation, which makes us wonder whether it was a written contract at all.

Lili's situation contrasts with that of Henrique Resta. Although she was also unknown in São Paulo, her contract with the Casino turned her into primarily a café concert singer who lived in a luxury brothel, and to any inhabitant of the city that meant that men paid her way for her in exchange for her company. Her identity as a variety artist included a combination of her performance at the Casino with her duties as prostitute at the artists’ boarding house. In contrast, Resta's identity was rapidly defined in terms of his relationship with the young singer, but because he spent no money on her he was cast in the role of gigolo.

The notion of exploitation in such cases becomes even more clearly evident in another case of expulsion which occurred the following year. In 1912, a troupe arrived from Buenos Aires at the port of Santos, in Brazil. Like Lili Bijou, they too had a contract to perform in São Paulo's Casino theatre. Eighteen-year-old Marcelle Parisy, a Frenchwoman, was a member of the troupe, but her escort, the Belgian Arthur Van Der Elst, was not.Footnote 49 In view of the widespread publicity attributed to “white slavery” stories, the port authorities were suspicious of the couple and did not allow Van Der Elst to disembark. Marcelle and Arthur both claimed they had met by chance on the ship, having known each other in Paris when they worked together in the Bouffes Parisiennes theatre. Furthermore, the Belgian introduced himself as a theatrical agent, explaining that he was in Brazil for just a few weeks to negotiate a tour to São Paulo for a dramatic theatre company. We can only speculate as to whether they were finally allowed to disembark because the ship and port authorities found their story convincing, or only because Marcelle refused to disembark without Arthur.

Perhaps it was thanks to the intervention of the Casino's theatre director that all ended well for Marcelle and Arthur, for it was the director who was in charge of collecting the artists at the port, taking them to São Paulo by train, and dropping them at their hotel. He even recommended a boarding house for Van Der Elst once the port situation had been resolved. The director's presence at the port confirms the multiple responsibilities of some of the key people in the variety business. Although the multiple-show system demanded increasing specialization of tasks, by the 1910s it was still common to find writers who were also in charge of rehearsals, art direction, or who doubled as mediators between multiple players, such as costume designers.Footnote 50 In such cases, the director would have to manage logistics.

In the case of Marcelle and Arthur, as the first to make a statement in the subsequent police investigation, it might have been that the director was the one who first accused the Belgian of being Marcelle's procurer. The local police chief heard too the testimony of the owner of the boarding house where the suspect stayed, and his statement was exactly what the police needed to proceed with the expulsion: the boarding house owner had seen Marcelle giving the Belgian all the money she earned from other men's visits. He “supposed that Van Der Elst exploited her and demanded she give him her money”. Marcelle Parisy explicitly denied that Arthur was her lover, stating instead that he was “just a client”. Nevertheless, in less than a month Van Der Elst had been expelled.

The expulsions of Henrique Resta and Arthur Van Der Elst share important characteristics. In both cases, the male escorts of performers were accused of procuring after a brief police investigation, which consisted of a few statements by witnesses. Having no fixed occupation on account of their travelling, and being romantically involved with women who stayed in houses renowned for being brothels, men such as they were therefore vulnerable to accusations of profiting from those women.Footnote 51 In both investigations, witnesses considered that sexual availability seemed to be only natural in relation to the women engaged as performers by the Casino theatre in São Paulo. The fact that their work contract required prostitution, or at least rather implied it, was utterly relevant. In both cases mentioned here, the police focused on proving that exploitation took place between the newly arrived couple. For that, it was as important for them to obtain statements from the women who had been giving money to the defendants as it was to establish that the men had no other contacts, and that they had no profession nor known position.

Police investigations placed under scrutiny what appeared to be complex affective relationships, although expulsion records are not reliable sources for describing the exact nature of the couples arriving in São Paulo from Buenos Aires. That is partly due to the fact that authorities were interested only in gathering evidence to turn an individual suspected of procuring into an expelled foreigner. In that sense, the records in fact reveal how the police went about actually creating “undesirable” types. Looking at how the police understood the broadly defined Brazilian legislation on procuring, we can see that the blurred lines between life and work in female artists’ lives could potentially cause any man associated with them to be suspected of sexual exploitation. In addition, and for reasons that are hard to fathom, in both our cases here the women were more concerned in their testimony with protecting their partners than with explaining what they themselves actually thought of their relationships.

However, police records do reveal some dimensions of women's lives in the entertainment industry. Henrique Resta and Arthur Van Der Elst were accused because the relationships they had with the Casino theatre artists vexed other men who had their own agreements with those women. Because of that, more subtle aspects of the artists’ lives and work arrangements come to light. Police authorities considered that there was nothing illegitimate about the relationships women artists established with their employers and landlords, who acted within a virtual network of intermediaries connected to the business of entertainment, which seems to have included prostitution. Because of that, expulsion investigations record the usual goings-on of the world that surrounded women's work, whether that meant singing and dancing at the Casino, or having sexual dealings with a variety of men.

Neither boarding-house owners nor Casino employers were accused of exploiting women artists – even though the former facilitated living conditions for prostitution, which was one of the definitions of procuring contained in Brazil's Penal Code, and the second fitted the description of what the League of Nations would later consider “white slavery”, since the low salaries they paid were considered to amount to economic pressure on women artists to turn to prostitution. In the context of expulsion investigations, sexual exploitation did not seem to include the broader notion of facilitating or inducing someone to take up prostitution, but was seen in a rather narrower sense of profiting from prostitution.Footnote 52

Police records also shed light, indirectly, on the artists’ perceptions of the agreements established with their intermediaries and employers. Lili Bijou and Marcelle Parisy might have felt they had a certain amount of room for manoeuvre, perhaps even to the point of breaking an implicit rule of working arrangements – not to bring their own men with them, for instance. From that perspective, Casino contracts were not in fact simply a front for the “smuggling of women”, simply because such contracts – whether written or verbal – did not have a single function. In fact, the stories of Lili Bijou and Marcelle Parisy suggest that men had competing vested interests in women like them.

In the tours through South America, work contracts were rather a defining element of women's identities as artists during their travel and during their stays. Contracts established the legitimate terms of their relations with others, and accusations of sexual exploitation were applied to relationships deemed unacceptable. Therefore, the moral terms used to define boundaries between acceptable and unacceptable behaviour were established in very particular settings, among the competing interests of men in relation to women's activities as artists and prostitutes. However, and despite their vulnerable position, women artists developed strategies to deal with such relationships. Mobility played a crucial role, as it was part of their contractual obligations, but at the same time it could create the possibility for them to be rid of what they considered to be undesirable escorts.

FAMILY CONTRACTS

Not all foreigners expelled from Brazil under accusations of procuring were the male escorts of women artists. If the most popular figure of white slavery was the young man playing the role of seducer, in theatrical settings it was quite common to feature the mother as her daughter's career manager. When family structure forms part of labour intermediation practices, it reveals different aspects of contemporary views of female and child labour in the entertainment industry, as well as of the survival strategies of women artists. In such family settings, vulnerability became the major characteristic.

In 1913 Costa Junior, a man of the theatre accustomed to performing multiple tasks in the entertainment world – as composer, writer, teacher, and director – noted something strange about one Max Werman's family, and notified the police.Footnote 53 Famous in Rio de Janeiro for composing the music for a successful play in 1909, Costa Junior also worked as an agent for artists. Junior testified that he had known the Wermans for a long time, because a few years earlier he had hired the Werman children for a play. After that, the Wermans had retired to Buenos Aires, and according to Costa Junior their sudden reappearance in Rio de Janeiro, where they wished to negotiate a contract for their daughter Rosita at the Pavilhão Internacional, one of Paschoal Segreto's establishments, raised disturbing rumours. He had heard from other artists that Werman had “traded his daughter's honour in Buenos Aires”, and that the police of both Buenos Aires and São Paulo had expelled him from their cities.Footnote 54

The return of the Wermans to Rio offers a glimpse into work relations involving family networks, as stated by witnesses called during police procedures to expel Senhor and Senhora Werman. After Costa Junior filed his complaint, the first person who was keen to say something about the case was a nineteen-year-old carpenter who had worked for the Wermans in Buenos Aires and Rio. As a family employee, he had all kinds of scandalous tales to tell, especially of how Rosita's parents offered her to men who would pay for each rendezvous. Meanwhile, a neighbour was willing to testify that he saw the “young lady copulating (with her clients) in the living room”.

Teresa Nelson, a Spanish artist employed at the Maison Moderne (another of Segreto's establishments), also testified against Max Werman. She was married to a painter employed at the Pavilhão Internacional, so the whole family was engaged in the entertainment business. Their daughter used to keep company with Rosita Werman. The two girls frequented places considered by all witnesses as inappropriate for them, such as the Palace Theatre and the Palace Club, featuring not only variety shows but gambling and prostitution too. Teresa Nelson's daughter was mentioned in Costa Junior's and the carpenter's statements, so it is probable that Senhora Nelson had some explaining to do at the police station in order to protect her own daughter's honour. In her defence, she claimed that when she realized that the Wermans were not “honest people” she forbade her daughter from seeing Rosita Werman again. She had first known the Wermans as “poor people and they were now covered in jewellery and had a lot of money provided by the exploitation of their daughter Rosita”.

The establishments belonging to Paschoal Segreto mentioned in all the above testimonies were among the most popular in Rio de Janeiro at the time. The Wermans and the Nelsons obtained contracts to perform different jobs there, but while the Nelsons could prove that they were still working, Max and Carmen Werman confessed that they lived exclusively on the money earned by their children as artists. Teresa Nelson's accusations against the Wermans therefore highlighted a moral difference between the two families. Senhora Nelson presented herself and her husband as hard-working people who worried about their daughter's virtue, although it was clear from other testimonies that both girls often went together to places considered by all witnesses as unsuitable. Nevertheless, Teresa Nelson sought to establish a distinction between what she considered workplaces (such as the Maison Moderne or the Pavilhão Internacional) and other places inappropriate for their daughters (such as the Palace Club or the Palace Theatre). Therefore, even if she was unable, or unwilling, to control her daughter's wanderings in the city as the police authority would have expected, she maintained that work for female and child performers in the entertainment business was quite compatible with honest and hard-working family life.Footnote 55

For all witnesses, the immorality of the situation was not in the contract, nor in the fact that the Wermans' children worked in Segreto's establishments. Costa Junior himself had no difficulty in admitting that he hired child artists. Furthermore, the Wermans' son's working conditions were never questioned by the police, even though Senhora Nelson accused the Wermans of “living off the prostitution of their daughter Rosita and the work of their son Luiz”. Costa Junior also mentioned that Max Werman used to “exploit” the wrestler Muller, but the police were not interested in that either. Once again, their justification for expelling Werman was that he exploited his own daughter – he forced her to prostitute herself and profited from the money she made from it. Despite the incriminating testimonies, the police chief preferred to send the Wermans away rather than prosecute them for procuring.Footnote 56 Although Senhor Werman left the country a few days after the investigation had begun, within a month both the Wermans were facing decrees of expulsion.

As extreme as the Werman case might have been, it nevertheless illuminates common strategies of family work in the entertainment business, many of them probably related to older traditions inherited from circus families who had been travelling throughout South American cities for decades.Footnote 57 Families travelled and worked together and it was usual for parents to negotiate their children's contracts in the entertainment business. Many parents, whether more or less successfully than Teresa Nelson, struggled to define the moral boundaries that separated them from certain places, people, and practices they considered reprehensible. Although night tours of the city by their daughters might have blurred those boundaries, many parents held dear the trope of the “theatre family” and the “circus family”.Footnote 58

The confluence of labour intermediation and sexual exploitation in Rosita's parents, particularly her father, makes their case completely different from the expulsions discussed above. Although there is no statement from Rosita herself in the police records and no reference is made to her age, her extreme vulnerability vis-à-vis her father was abundantly clear to everyone involved. While for Lili Bijou and Marcelle Parisy prostitution was part of their activities as artists at the Casino theatre, for Rosita prostitution was a parental imposition. Everyone agreed that Werman's mediation in the prostitution of his own daughter and the fact that he himself did not work was unacceptable.

But even in that extreme case, ambiguities remained. Costa Junior and Teresa Nelson seemed to conceive of a broader notion of exploitation than the one applied by the police (suggesting that the wrestler Muller and Werman's son were also his victims). Although witnesses portrayed Rosita as a victim and the Nelson girl as a somewhat more sheltered daughter, both with little or no room for manoeuvre, the girls actually went willingly to nightclubs, thus blurring the spatial moral boundaries adults insisted on trying to reinforce. Police intervention reduced all those dimensions to the single plot of the abusive father and the victimized daughter.

The investigation that led to the expulsion of the mother of yet another young singer, who coincidentally was also called Rosita, further reveals familial strategies in the international routes of variety entertainment. In addition, this is a rare case that also sheds light on the personal strategy of the young woman concerned in her efforts to confront her intermediary – in this case her own mother. Known as “Bella Rosita”, she had been hired as a “Spanish singer” to perform in Buenos Aires, Montevideo, and other Argentine cities before she arrived in São Paulo in 1915.Footnote 59 In contrast to the stories discussed above, in this case her tour did not include the Casino, nor any other of Paschoal Segreto's establishments, but rather cabarets. That in itself seems to confirm the growing importance of a new setting, where the mixture of prostitution and variety theatre was more straightforward.Footnote 60

Mother and daughter arrived with a contract for “Bella Rosita” to sing at the Montmartre cabaret, which also doubled as a boarding house, for which she would receive 30,000 réis per night, a sum actually collected by her mother. (It is interesting to note that Señor Werman was accused of receiving 100,000 réis for each rendezvous between his daughter and a client.) Thus, Rosita worked and lived in the same place, and when the contract with the Montmartre was over, Bella Rosita started singing at the Apolo theatre and the Café Paris cabaret three times a week, moving to another boarding house along with her mother. Rosita herself provided the information about her whereabouts to the police, when she accused her mother of keeping all the money she, Rosita, had earned. She also gave the police precinct chief a list of possible witnesses who could attest to her situation, including her landlords and several women, most of them Italian performers who were older than she.

If the statements her co-workers gave were truthful, Rosita's situation was indeed tragic. They mentioned suicide attempts, and regretted that no man who might have been willing to protect her could get near her, because all the money she earned ended up in her mother's pocket. All the witnesses stated that Rosita's mother expected to take advantage of her daughter's youth so that both could return to Buenos Aires as rich women. From five statements by women artists, it becomes clear that they did not expect to become rich through their work as singers, but rather through the protection, favours, and money given them by the patrons of the places where they worked and lived. Thus, many seemed to live in hope that they could benefit from moving from one cabaret to another, or from one boarding house or theatre to the next, just as Lili Bijou had done at the beginning of the decade. Their existence as travelling artists could scarcely be called a lifestyle, but rather a temporary strategy to profit from their work.

The comments from Bella Rosita's friends working on the stages of South America hint at the meanings some of the young women attributed to the sex trade. Maria Fantini, an Italian singer who was staying in the same boarding house as Bella Rosita and her mother, testified that Rosita had told her that she “would work as a prostitute once she got rid of her mother, because the latter had extorted all the money she earned, even to the point of not having a stitch to wear”. The Spanish Vicenta Gual, who had known mother and daughter since the time they had lived in Entre Ríos (Argentina), when they had all worked together at the Teatro Variedad Tinti, also stated that Rosita's mother “extorted [sic] all the money she earned from her honest work”. For her co-workers, Rosita's exploitation lay in her mother's daily “extortion”. From their perspective, immorality included both the sexual and the stage work forced on Bella Rosita by her mother, and her appropriation of Rosita's earnings.

As in previous cases, police investigations reveal valuable clues about women artists’ work routes. In Entre Ríos, Bella Rosita had sung in a duet with her aunt, while the Spanish Vicenta was a singer of Italian tunes. Italians Guia Caiaffa and Margarita Fabris also knew Rosita from the time they all worked at the Teatro Cosmopolita in Buenos Aires, at least three years earlier. Thus, at eighteen, Rosita was very well acquainted with the life of a variety artist, travelling with her family. She had worked mainly in Argentine cities until her mother decided to broaden their horizons, which showed the cleverness of her mother's timing. Bella Rosita's view of her mother's exploitation would later be partly shared by the police: the biggest problem was not prostitution per se, nor the economic constraints that led Rosita to prostitution, but rather the fact that someone else kept all the money obtained by Rosita's activity.

One of the most relevant aspects of the case – quite different from those discussed above – is that we have first-hand information because it was Bella Rosita herself who made the move against her mother. Contrary to what the League of Nations investigators would find ten years later, although Bella Rosita was in a vulnerable situation she was not isolated at all. If she had been, how could she have managed to find five women willing to go to the police and testify against her mother? The owner of the boarding house might have been persuaded to make a statement because the two women had left his establishment without paying their bill, but the other women seemed genuinely outraged at Rosita's mother's actions and stated that they were prompted by what one of them called “stage camaraderie” and “friendship”.

The cases of both Rositas leave no doubt about the violence and abuse that could be involved when direct relatives mediated young women's labour. In those particular situations, the expulsion investigation focused on the tutelage of parents over the work of their daughters as entertainers, which was easily characterized as procuring. However, it is also true, at least in the case of the second of the Rositas, that the experience of crossing borders – due to work contracts that facilitated Bella Rosita's reunion with older friends and previous acquaintances from her stage appearances in Argentine cities – allowed her to use the repressive legislation on the expulsion of foreigners in Brazil to her own benefit. Therefore, in the struggle for autonomy as a young woman artist vis-à-vis her own mother, she was able to enlist many allies.

EXPLOITATION AND THE MEANINGS OF CONTRACTS

For some historians of national theatre in Argentina and Brazil, the pre-World-War-I era signalled the peak of variety entertainment. In their accounts, the interruption of communications between Europe and the Americas during the war was critical because it allowed for the development of national companies, and therefore of a “true” national theatre.Footnote 61 However, considered on its own terms, the prewar period tells us more about the vital role of international routes in the entertainment and cultural market of South American cities. More investment together with the growth of European immigration fostered a significant increase in the circulation of artists during the first two decades of the twentieth century.

Different types of intermediary played a key role in the labour market of the entertainment business in South American cities. Considered a minor genre in the performing industry, variety theatre – featuring travelling artists and hinting at different modalities of male entertainment, including the sexual – involved work relations characterized by moral ambiguity. Thus, the actions of those who were related to women artists and interfered with their earnings came under the scrutiny and suspicion of their contemporaries. In that context, variety theatre becomes then a privileged site for analysing the relationship between work and morality.

Moral boundaries within the business and the degree of autonomy permitted to women artists were negotiated by contemporaries in specific social settings, in answer to a larger concern over the circulation of young women across international borders. Two meanings of immorality seemed to coexist and sometimes mingled in such negotiations. First, the immorality of sexual exploitation in the context of affective (sometimes familial) bonds; and second, the immorality of work exploitation in a wider sense, where prostitution derived from the vulnerability of young women artists who found themselves in harsh and precarious work conditions. In both, work contracts were seen as a guarantee of unequal and coercive relations, but in the end neither the League of Nations experts nor participants in the entertainment world, and certainly not the police, could trace precisely the fine moral line that separated “properly managed troupes” from those which were used to disguise organized prostitution. Whereas many of them believed a genuine separation did in fact exist and could be identified, they could not isolate sexual exploitation from regular work exploitation. Rather, they ended up unveiling, directly or indirectly, the larger context of a growing entertainment labour market.

In order to succeed in their goal of expelling “undesirable” foreigners, the interests of the police lay in emphasizing a single meaning of exploitation – as the expropriation of money gained by women from prostitution. A close reading of police investigations reveals, however, that multiple meanings of exploitation were at stake in labour arrangements. Work and affective relations were far from univocal to witnesses, victims, and suspects. According to police investigations of male escorts of female performers, work contracts drew a distinct line between legitimate (employers, landlords, stage managers) and illegitimate (escorts who allegedly kept the artists’ earnings) intermediaries.

Moral boundaries were also the concern of a number of people in the entertainment world, especially in the face of what they perceived as improper behaviour of the young women artists themselves. As for them, some insisted on crossing boundaries by exploring the city's expanding nightlife, while others rebelled against their mothers for depriving them of the money they made, although not for making them work as prostitutes in the first place, as the League of Nations observers might have imagined.

Apart from detailing the routes and work relations of women artists and their escorts, police records of expulsion also offer a chance to reassess the moral ambiguity that characterized women's experience and their vulnerability in that labour market, as strategies of survival, accumulation, and upward mobility developed by artists and their families. In that sense, the spatial mobility that work contracts guaranteed was far from being univocal. Contracts actually bound young women to fulfil both explicit and implicit work requirements, but they also allowed them, as Bella Rosita proved, to participate in the social fabric of a “stage camaraderie”, where they could meet other artists and recognize a shared experience, which was surely made up of more than what those brief records allow us to glimpse. What we can see though is that young women's perceptions of what it meant to cross the morality boundary, and what exploitation meant, might be very far from what the police or League of Nations observers could imagine, even if some meanings could be shared by all.