On 27 January 1954, Heitor Brugners, the director of the Friends of Vila Palmeira Society in a neighborhood to the north of the city of São Paulo, wrote a letter requesting that Jânio Quadros, São Paulo’s mayor who would later be elected president of Brazil, intervene in an ongoing matter with São Paulo Light and Power, the Canadian company that held the concession for the city’s public lighting. Brugners hoped that, with the mayor’s help, the powerful concessionaire could be convinced to install streetlights in his neighborhood, in the far outskirts of the city.Footnote 2 In June of that year, residents of Vila Independência in the town of Ipiranga likewise directed a petition to their city’s mayor by way of their local Neighborhood Friends Society (Sociedade Amigos de Bairro). This petition, like their counterparts in Vila Palmeira, asked the mayor to intervene with The São Paulo Light and Power Company, to request the installation of an external energy connection to power the existing streetlamps in their districtFootnote 3 of “approximately 30.000 inhabitants”, to achieve “JUSTICE” in “finding a solution to one of the most sensitive problems, since a large number of workers, young women and men, suffer all types of danger, from accidents to assaults”.Footnote 4 And the president of the Vila Ipojuca Friends Society, in São Paulo’s Lapa district, claiming to speak on behalf of residents, made a similar plea for public street lighting in his area, in a petition to the mayor dated 1 September 1954, which also included several other requests.Footnote 5

These types of letters, requests, and petitions addressed to public authorities in São Paulo were common in the post-World War II period. In general, these communications were sent via so-called Neighborhood Friends Societies (Sociedades Amigos de Bairro, or SABs), a form of association for local residents that emerged and proliferated in the city from the late 1940s. From the end of the Estado Novo dictatorship, under Getúlio Vargas, in 1945, until a military coup in 1964 instated a dictatorship that would last for more than twenty years, Brazil lived through its first experience of mass democracy. In addition to regular elections, workers and popular sectors in general managed to significantly expand both their level of self-organization and their ability to make claims vis-à-vis the state, thus increasing their weight and say in public affairs.

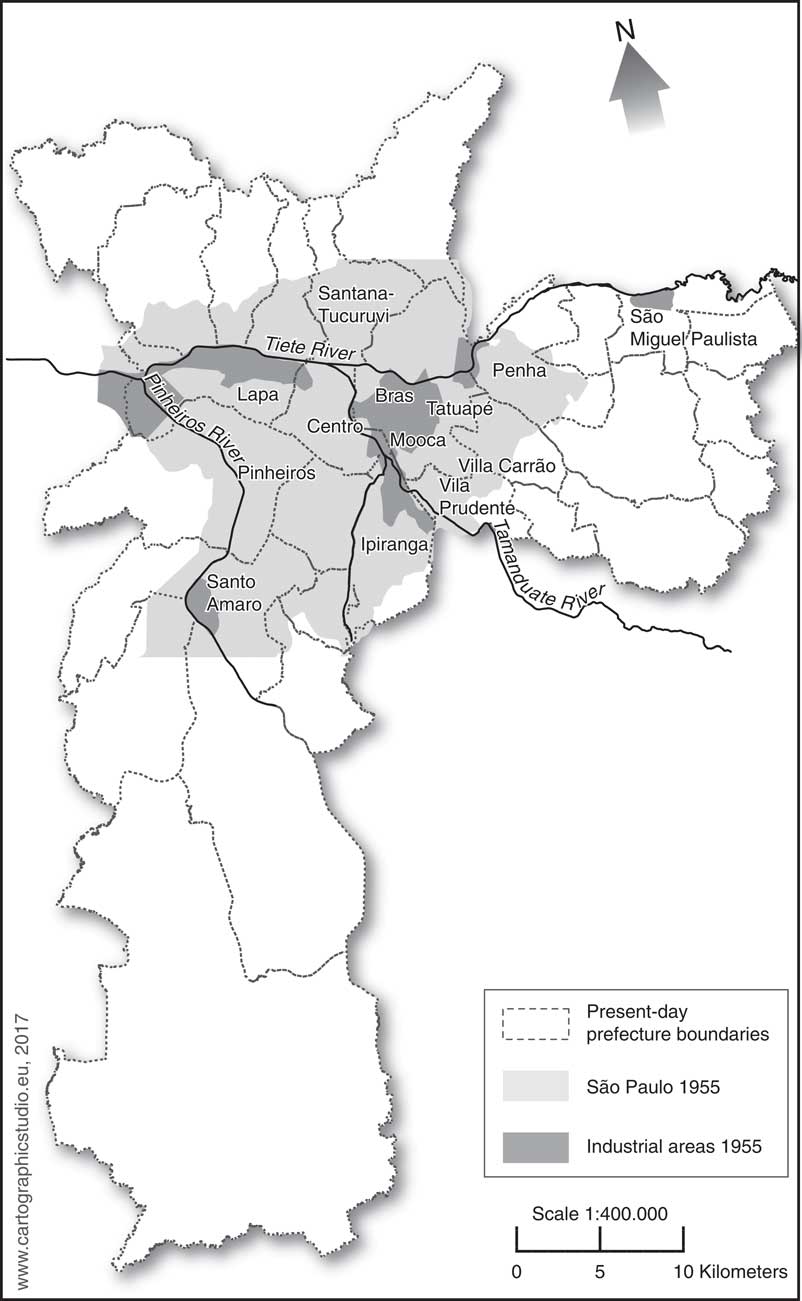

Figure 1 São Paulo’s industrial areas in 1955.

In this context, the tendency to form popular associations based on neighborhoods (and the specific territorial space they defined) gained strength and came to characterize the history of social movements and political life in São Paulo and its surrounding industrial towns. Tenants’ organizations, residents’ associations, Neighborhood Friends Societies, favelas organizations (informal housing settlements), sporting and recreational clubs with strong local ties, etc. made up the exceedingly diversified and complex mosaic of the associative lives of urban workers, which had political and social repercussions that, at many points in the city’s twentieth-century history, transcended the local level. This dynamic was fundamental to the city’s class formation process, and it frequently developed in tandem with the more “classic” workers’ movement defined by unions and political parties.

Between 1940 and 1970, São Paulo and the cities that surrounded it (in what would come to be known as the metropolitan region of “Greater” São Paulo) experienced an industrial boom and an impressive urban and population expansion (a process that would continue in the four decades to follow), transforming São Paulo into one of the largest cities in the world. Two characteristics of this vertiginous, dual process of industrialization combined with urbanization stand out. First, São Paulo’s twentieth-century urbanization process is characterized by its tendency to segregate by class, marked as it was by the intense and continuous expulsion of the poorer classes from the central regions to the peripheries of the city. This “peripheral pattern of urban growth”, to use a term well-established in the specialized literature, marked urban development in the post-war period:Footnote 6 A large part of the working population came to live in peripheral areas that were increasingly removed from the urban center and increasingly bereft of urban resources, widening the geographical, social, and cultural distances between the city’s different social classes. The magnitude of the wave of immigration during that period further accelerated the creation of neighborhoods in the peripheries, especially in the eastern and southern regions of the city. A greater distance between one’s home and work (although a sizeable portion of the workers found jobs in these peripheral neighborhoods), a growing dependency on public transportation, in particular buses, and individually owned houses constructed by their residents in peripheral lots are some of the most distinctive characteristics of the daily experiences of São Paulo’s working class during this new era. A second feature of the history of urbanization and industrialization in São Paulo concerns the importance of these neighborhoods as spaces of conviviality and sociability, especially for the popular classes.Footnote 7 They were fundamental spaces for the formation of social networks and common experiences – in both the work sphere and residential life. A place of residence, leisure, and labor, one’s neighborhood also contained the entire spectrum of personal relationships with family members, friends, and neighbors, equipping workers with knowledge and personal contacts that were essential to quotidian life. Unsurprisingly, Jorge Wilheim, a famous Brazilian urbanist concerned with urban planning between the 1960s and the 1980s, emphasized the strong local identities that centered on neighborhoods: For him, the neighborhood was “the urban unit, the most legitimate representation of the spatiality” of the population of the city of São Paulo.Footnote 8 Even today, the idea of a city historically forged by various local identities seems to have endured. The French anthropologist Oliver Mongin, for instance, recently stated that São Paulo is still “made up of multiple and varied neighborhoods, in which we feel a strong sense of autonomy”.Footnote 9 In the decades following World War II, the experiences of residents of the neighborhoods in São Paulo’s, especially, in the expanding peripheries, were powerfully marked by a general dearth of urban infrastructure. But disillusionment with the promises of urban progress and the growing perception that inequalities and exploitation also pervade the urban fabric provoked a burst of associative activity, for which the neighborhoods would provide a common thread and a central identity.

This article seeks to analyze these residents’ associations organized around specific neighborhoods between the end of World War II and the coup in 1964. It examines, in particular, the veritable boom of associative activity that centered around SABs at the beginning of the 1950s and its relationship with local politics. In addition, this study explores connections between neighborhood associations and labor union struggles at the end of the 1950s and beginning of the 1960s, a period of major political polarization and the affirmation of a language of rights centered around the universe of labor. Based on strong social networks and informal relationships created by workers,Footnote 10 I argue that organizations like the Neighborhood Friends Societies were fundamental to the construction of political communities that had a powerful impact on electoral processes and on the formation of the state at the local level. Likewise, this article will show how, during that period, identities at the neighborhood level frequently developed in dialogue with processes of class formation, staking claim to a language of rights associated with the condition of being a worker and, simultaneously, a citizen. Finally, seeking to bring my own research agenda into dialogue with a transnational perspective, this article suggests how analyses with such a localized scope, like those focused on specific working-class neighborhoods, can intervene in debates concerning Global Labor History. Despite the broad recognition of the importance of neighborhoods and residential locales to processes of class formation, the body of research conducted from a global studies perspective still appears to undervalue the comparative and transnational potential of “local” studies undertaken with a “micro-analytical” approach.

NEIGHBORHOOD FRIENDS SOCIETIES AND POLITICAL LIFE IN SÃO PAULO IN THE 1950sFootnote 11

On 29 March 1954, Mayor Jânio Quadros’s office received a letter with claims made by residents of a far-flung neighborhood in the north zone of the city. The missive was signed by Moacyr Lázaro Barbosa, Mario dos Santos Lourenço, and Magnólia Pires de Souza, respectively the president, council president, and the secretary-general of the Vila Gustavo Friends Society. The typewritten text, written on the Society’s letterhead, which indicated that the entity had been founded on 20 June 1948, requested, “in the name of the approximately 1,500 members” of the organization, that the city provide “public illumination on Avenida Júlio Bueno, because this is a main, inter-neighborhood avenue [...] on which the Vila Gustavo buses travel”. The authors of this brief letter closed by emphasizing their certainty that the mayor would attend to their “appeal that this Society is making to him”, which aimed to “interpret and transmit to the appropriate authorities the anxieties of this forgotten, proletarian population, which, although humble, also contributed to São Paulo’s development and its greatness”.Footnote 12

Requests such as this one, sent directly to the mayor, were common in those years. Indeed, every day the mayor’s office was flooded with letters, messages, petitions, and claims authored by the newly formed and territorialized Neighborhood Friends Societies (Sociedades Amigos de Bairro, SABs).Footnote 13 It is difficult to trace the emergence of the first Neighborhood Friends Societies. Associations with this curious name, however, seem to have first appeared in the late 1930s and early 1940s, probably inspired by Friends of the City Society (Sociedade de Amigos da Cidade), an organization created in 1934 by engineers, urbanists, and other middle-class professionals (including Francisco Prestes Maia, the city’s mayor from 1938 to 1945). These pioneers in shaping an association in São Paulo concerned with the city’s development, in turn, seem to be have been inspired and influenced by the Friends of the City of Buenos Aires Society (Sociedad Amigos de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires) and by the local development associations (Sociedades de Fomento) that proliferated in the neighborhoods of the Argentine capital during that period.Footnote 14

Yet, it was only during the years immediately following World War II that São Paulo would experience a visible surge in residents’ organizations with an expressly local and territorial character. Particularly encouraged and influenced by the then-ascendant Communist Party (Partido Comunista do Brasil – PCB), the neighborhood-based groups quickly spread through working-class areas of the city, under the name of Democratic and Popular Committees (Comitês Democráticos e Populares – CDPs), expressing a wide-ranging set of demands for urban improvements, administrative decentralization, and democratization of urban governance.Footnote 15

In the political vacuum brought about by the criminalization of the Brazilian Communist Party in 1947 and the consequent extinction of the CDPs,Footnote 16 some of those previously involved in them as well as other activists reoriented and organized themselves under the name of “Neighborhood Friends Societies”. In this same vacuum, Jânio Quadros (1917–1992),Footnote 17 a previously obscure local assemblyman, managed to capitalize on and collaborate with this new civil society movement based in São Paulo’s working-class neighborhoods and cultivated an interrelation between these and the city’s authorities as no other politician had before.

It was precisely in the context of his mayoral campaign in 1953 that the Neighborhood Friends Societies gained public prominence. The election of Jânio Quadros came as a surprise to the world of traditional politics. Quadros’s victory would be called the “Revolution of March 22nd” by his allies, in a reference to both the date of the election and to the magnitude of the transformations that he sought. But the electoral triumph revealed, above all, the power of the vast support base he had built, in a relatively short time, through the SABs in São Paulo’s working-class neighborhoods. During his exhilarating campaign, Quadros made the neighborhood residents’ demands his own, and, receiving 65.8 per cent of the vote, he won an astounding victory, in particular in the city’s peripheral districts. From then on, it would no longer be possible to pursue politics in São Paulo without taking seriously the SABs and their claims and demands.

Quadros’s victory and the expectations it generated gave the existing SABs a huge boost: By way of mobilizations and claims sent directly to the new leader of the local government, the SABs tried to take advantage of the momentum created to demand improvements for their districts. Apparently, Quadros’s victory also accelerated the formation of new residents’ associations of this kind. Judging from the dates when these associations were created, found on the logos printed on the correspondence that they sent to the mayor, several of these “Sociedades de Amigos” were founded in the period immediately following the election of the new mayor.

Moreover, in the immediate wake of the election, a major wave of industrial strikesFootnote 18 reinforced the pressures on the new mayor, who had been elected as the “champion of the periphery”. Aware of the political potential of these associations and clearly interested in keeping himself close to them, the mayor encouraged the neighborhood associations as they took on a more active role in public life in pursuit of their interests. The mayor’s view of the SABs as welcome protagonists in São Paulo’s urban politics, becomes clear, for instance, in a petition with more than 6,000 signatures, addressed to Quadros and sent by the Vila Izolina Mazei Friends Society. The residents of this neighborhood, defining themselves as “all poor workers”, demanded that a series of improvements be made to the region and reminded the mayor of the speech “solemnly delivered at the Moinho Velho Friends Society, and published in the [newspaper] A Gazeta”, in which Quadros had “called upon its residents to formulate their requests concerning public improvements whenever possible, by way of their NEIGHBORHOOD FRIENDS SOCIETIES”.Footnote 19

Many requests were sent asking the mayor to serve as an intermediary between neighborhood residents and companies holding concession contracts to provide telephone services (Companhia Brasileira de Telefones) or electrical energy (The São Paulo Light and Power Company, known simply as “Light São Paulo”) in order to provide the neighborhoods with a telephone (to be installed, in general, in a local pharmacy or bakery) or with street lighting. These cases, which were dealt with in direct action-style on the part of the secretaries and departments of the mayor’s office, were rather opportune occasions on which Quadros could don his hero’s cape and apply pressure to utility companies like Light São Paulo, the target of his virulent attacks since his time as a city council member.

In this regard, speed seemed to maintain the mayor’s image of a personal relationship with his constituents and his responsiveness to their needs. The directors of the Vila Olímpia Friends Society, for instance, in a letter dated 12 April 1954, requested that the mayor have a public telephone installed in a neighborhood bakery, reminding him that “as Your Excellency has already explained to us verbally, the lower part of the neighborhood has no telephone whatsoever, which makes urgent communications impossible”.Footnote 20 Only two days later, Quadros responded to the Society, confirming that he had already placed a request to the company for the telephone line and the telephone itself.

The majority of these requests consisted of pleas to pave the streets, install telephones and public lighting, collect trash, create public markets to supply people with basic foodstuffs, and start or extend bus lines. The range of demands included the installation of a children’s playground, a neighborhood daycare center, or the placement of curtains and blinds in a public school in the area. At times, this came with detailed information (including maps) about where these new establishments should, ideally, be located.Footnote 21

Figure 2 Many SABs were created in connection with amateur football and recreational local clubs in the working class districts of the city. Library of the São Paulo Chemical Industrial Workers Union. Used by permission.

Beyond their role in making claims on behalf of and mobilizing residents of the neighborhood, the Friends Societies were also sociable and leisure spaces. As several studies show, many of these societies originated in or were associated with local sporting (particularly amateur soccer) and dance clubs and organizations devoted to entertainment in general.Footnote 22 Thus, it should come as no surprise to find amid these many demands for urban improvements a request for a license made by the Tremembé and Zona da Cantareira Friends Society, “to carry out four Carnival balls and two children’s matinees, as part of the celebrations during the days of Carnival”, in February of 1953.Footnote 23 Other local institutions and organizations also recognized the channels that opened up between the SABs and the municipal authorities and directed their own, particular appeals through neighborhood associations. This was the case, for example, in some local parishes of the Catholic Chuch. In Vila Palmeiras, Egisto Domenicali, the president of the local Friends Society, made a request on behalf of Father Antonio de Fillipo, asking the mayor “to pave the area in front of the parish church [of the neighborhood]”.Footnote 24

Public works were one of the most common demands, the pavement of roads in particular and construction projects in general. To have the street paved was generally a precondition for demanding further improvements, such as street lighting and public transportation. Again, this had been in part instigated by Jânio Quadros himself, who, as soon as he assumed the position of mayor, launched an “Emergency Plan” for carrying out these improvements, in particular paving the streets.

The language of most of these petitions and other communications directed to the mayor’s office was far from begging for a “favor”. The tone was, generally, respectful and formal. The gratitude and praise for the mayor – pointing to his “high public spirit” and “elevated sense of justice”Footnote 25 – was matched by references to promises made by the mayor during his candidacy or during a visit that he had made to a particular neighborhood. These pieces of correspondence, whenever possible, highlighted the personal contacts that had been previously made with politicians or visits that residents had paid to the offices of government authorities. When asking “Doutor Professor Alípio Correia Netto”, Secretary of Hygiene in the Quadros mayoral administration, to install a public market in their neighborhood, for instance, the directors of the Vila Ipojuca Friends Society reminded him that the missive they were sending was simply intended to reinforce “what they had already had the opportunity to report to him in person”.Footnote 26

It was, however, through the use of the language of labor that the neighborhood residents represented in the SABs most insistently claimed their rights before the mayor. The authors of most of these petitions and letters mentioned repeatedly that theirs was a “working-class neighborhood”, and phrasings such as “the large numbers of workers, men and women”, living in Vila Independência in Ipiranga were not limited to this particular SAB. In a similar vein, the SAB of Vila Gumercindo emphasized that the neighborhood was made up of a “hard-working population of over ten thousand inhabitants”, while the residents of Vila D. Pedro II called themselves “humble laborers”, but ones who wanted “justice”.Footnote 27 The examples are many and recur frequently in the documents. The world of labor had, admittedly, already been valorized by the state for some time – the reference to labor and its association with citizenship rights had been a central characteristic of Getúlio Vargas’s government in the 1930s and 1940s (even if this was often only a rhetorical gesture). This continued and took on an even more complex and expansive dimension in the relatively democratic post-war period, when various political forces began to court workers. It is thus unsurprising that, under these circumstances, many workers (especially industrial workers), intensified their struggles for rights, tying these struggles to an identity and a language of class.Footnote 28 What is more remarkable, however, is how this identification was also embraced by a significant number of residents of poor neighborhoods, who underscored their condition as workers to express their demands for improved urban infrastructure and their part in the “progress” of the city. It was as workers, and not simply as individuals living in São Paulo, that an increasing number of residents demanded their rights to the city.

Jânio Quadros’s connections with the SABs were decisive for structuring a reliable, well-oiled political machine that the future president could count on for many years. Several of the presidents and directors of the Friends’ Societies remained ardent Quadros supporters, and some even built their own political careers. At the local level, the manifold claims and demands of neighborhood residents had established a stable channel of communication with the state, and, for neighborhood associations, this implied growing participation in urban politics. The capillary nature of the SABs’ relations and connections thus increasingly became an object of desire for politicians across São Paulo’s entire ideological spectrum. City Council members, in particular, whose electoral survival depended on securing a strong base in the neighborhoods, sought to establish their own privileged relationships with SABs and often tried to outdo each other in vocalizing and directing their demands to the executive authority.

Thus, from the mid-1950s on, it was not only Jânio Quadros and his followers that fought for representation in working-class neighborhoods by way of the SABs. The residents’ associations were probably the most politically pluralistic social movement of that era. If, on the one hand, a class identity could be and was typically claimed by the “Friends Societies” (and could only be appealed to by those who shared it, or claimed to share it as well); on the other hand, a neighborhood identity, another central characteristic of the association, was more open and easily addressed and adopted by politicians of different stripes.

A considerable proportion of the existing studies of the political relationships between poor residents and political leaderships in cities going through accelerated urbanization processes have tended to characterize such relationships as clientelistic, based purely on the logic of the “exchange of material benefits for votes”.Footnote 29 Thus, organizations like SABs functioned only as institutional mediators for the political schemes of clientelistic networks. According to this reasoning, the SABs would be a prototypical example of the populist logic of manipulation and cooptation. An important conclusion of this type of approach is a presumed fragility of civic culture and the absence of a tradition of autonomous organization of civil society in Brazil (and, one can say, in Latin America in general), this being a central element in the country’s lack of citizenship and democracy. In this type of analysis, however, the language and the actions of the Neighborhood Friends Societies and their constituents is typically neglected and subordinated to the logic of the state and its political leadership. Moreover, these studies seem to suggest a structural dichotomy between clientelistic networks and social mobilization. In contrast, the analytical efforts undertaken in this article aim to emphasize the perspective of the SABs and the agency of their participants. It is thus possible to understand how, in certain contexts, a language of rights associated with a discourse of class could be articulated and made binding even within a logic of domination and action that can be called clientelistic. Furthermore, following the trails blazed by such authors as Charles Tilly and Javier Ayero, neighborhood associations in São Paulo seem to confirm that “patronage and contentious politics can be mutually imbricated”.Footnote 30 As we shall see in the following, the SABs’ debates about decentralization and municipal autonomy and the approximation of neighborhood organizations with the labor unions and strike movements can offer interesting examples in this regard, as they point to attempts to develop other forms of action that were able to adapt to new constellations.

NEIGHBORHOODS, DECENTRALIZATION, AUTONOMY

Jânio Quadros only remained in the position of São Paulo’s mayor for about two years, swiftly moving on to be the state’s governor (1955–1959). While the principal constellation of considerable interaction between neighborhood associations and the city government continued under his successors, it is not surprising that the intense dynamic of the initial years soon wore off, not least because the city continued to expand and, with that, the number of new neighborhoods and urban challenges. In this situation, a new orientation emerged among numerous neighborhood activists, one that no longer sought closer collaboration with the existing authorities but, on the contrary, a move away from them. In the course of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s, a series of movements calling for the administrative separation of working-class neighborhoods arose in various places in the São Paulo metropolitan region. These movements consisted of several actors; yet, in many cases, as we shall see, SABs played a central role in them. Basically, these movements demanded the separation of neighborhoods and entire regions from the administrative control of the city of São Paulo and their transformation into autonomous municipalities, each with its own budget.Footnote 31 These movements shared the idea that their areas had been the victims of abandonment and forgetting, and that only with administrative emancipation through a secession from São Paulo would it be possible to bring local power into line with the population’s real necessities, especially in the poorest districts. The perception of a powerful injustice in the distribution of public resources on the part of the mayor’s office, which benefitted the city’s wealthiest, central neighborhoods to the detriment of the underprivileged periphery, was another common characteristic of the defenders of autonomy.Footnote 32

For a district to call for political and administrative separation, it was necessary to fulfill several requirements stipulated in the federal Constitution of 1946 and to carry out a plebiscite, which needed to be authorized by the State Legislative Assembly. Even when autonomy was approved by a majority of local voters, however, strong political and juridical resistance from municipal mayor’s offices confronted with such secessionist aspirations remained common, trying to prevent the territorial dismembering of their cities and the consequent loss of a population of constituents and of economic resources. Thus, the success of the processes of autonomy depended on a large and permanent popular mobilization, demanding both the build-up of political pressure as well as effective and proficient legal counseling.

This was the case with Osasco, probably the most famous and successful example of an autonomous district having seceded from the municipality of São Paulo. After its defeat in a first plebiscite carried out in 1953, the local autonomists reorganized themselves and managed to conquer the majority of votes when polling took place again in 1958. The São Paulo mayor’s office appealed the voters’ decision, followed by a long legal and political battle that inspired an impressive popular mobilization in the region. Osasco finally separated from the capital, becoming an autonomous city in 1962, when the newly formed municipality elected a mayor and city council members for the first time.Footnote 33

Estimates indicate that, between 1945 and 1964, seventeen peripheral neighborhoods attempted to separate from São Paulo. Invariably, the attempts and campaigns for autonomy involved the local SAB. In reinforcing the elements of a local, communitarian identity, these campaigns also highlighted all of the dissatisfaction with the precarious conditions in working-class neighborhoods. At the same time, the campaigns clearly demonstrated a building pressure to extend democracy to the local level and a popular mobilization for citizenship. This went beyond the realm of labor and union organizing, with urban poverty serving as an important concern and reference point for the consolidation of the struggle for rights.

Legal and political difficulties, however, frustrated most of these attempts. But other arguments also influenced the results of some of the plebiscites in the few locales where they did take place: For instance, in an initial attempt at separation undertaken by the populous neighborhood of São Miguel, in the extreme east of the city, the worst damage to popular support for the campaign for autonomy were caused by rumors that a future city of São Miguel would be considered part of the state’s hinterland, rather than an urban area and, as such, the salary index in force in this municipality would be held to a different standard from the capital city and other regions of the state and thus would be lowered. In contrast, the autonomists, trying to counter the arguments of the “No” campaign and, in particular, the salary question, demonstrated, for example, that in São Caetano do Sul (autonomous since the 1940s) the wages remained the same. What is remarkable about this dispute, however, is that both to defenders and opponents of separation the relevance of this labor-related issue seemed evident. Arguments directed at the residents as workers in this respect were broadly brought to bear on the campaigns, both pro and against autonomy.

At any rate, in the early 1960s, autonomist struggles in numerous neighborhoods resurfaced with great force, stimulated by the victory of the highly industrialized district of Osasco, which was officially made into an independent municipality in 1962. The vigorous mobilization and the victory of the autonomists in that locale served as an example of the possibility of secession and gave a strong stimulus to those that similarly argued in favor of the emancipation of their neighborhoods in various parts of the São Paulo metropolitan area. In addition, the new mayor of Osasco, Hirant Sanazar, as well as several city council members from the recently created municipality, gave their explicit support to the various autonomist movements in the capital of the state of São Paulo. Present at an autonomist rally in São Miguel in June of 1963, for example, Sanazar attacked those who opposed secession and reminded the gathered crowd, “four years ago the São Paulo stepmother did nothing for Osasco, only taking care of the elegant neighborhoods”, and, after enumerating a series of urban improvements in the newly autonomous municipality, like asphalted streets, health services, and urban cleaning services, he concluded, in a grandiloquent and messianic tone, that “autonomy means redemption”.Footnote 34

Beyond the uplifting example of Osasco, autonomy and the accompanying debate concerning administrative decentralization and the resolution of the urban problems that afflicted the residents of São Paulo’s working-class neighborhoods appeared to be directly related to the general mood favoring change and mobilization, brought about by the proposals of the so-called Basic Reforms Plan (Reformas de Base). This wide-ranging set of demands, which not only included measures for land, tax, educational, and constitutional reform, but also proposals for a decentralization and democratization of urban areas, were advanced during the presidential administration of João Goulart (1961–1964), a left nationalist who enjoyed considerable support from the labor movement. It is no coincidence, then, that in the early 1960s many labor unions and leaders became actively involved in movements for autonomy in neighborhoods in São Paulo.

The military coup in 1964 put a stop to all of the mobilizations and initiatives for neighborhood autonomy in São Paulo. With the road to actual autonomy blocked, many turned their attention once more to the mayor’s office, building up pressure (to the degree possible under dictatorship) for administrative decentralization as a way of attending, however partially, to the demands of peripheral neighborhoods. In fact, a decision, in 1965, by Faria Lima, the incumbent mayor, to create so-called Regional Administrations in many neighborhoods, sub-entities with the partial powers of a proper mayoralty, appears to have been a direct response to the mobilization of neighborhood entities and of the autonomist movement that had grown in São Paulo in the years just prior to the military coup. In the years to come, the SABs, which had not been proscribed by the military dictatorship, would come to play a fundamental role in urban politics. Although the political conditions were much more adverse than in the previous years, the socio-economic conditions of the neighborhoods compelled the SABs and other actors to continue their mobilizations and struggles. Consequently, the SABs increasingly went beyond the specific claims made by each neighborhood, and began to put the administration of the city as a whole and the role of the local government on their agenda.

SABs, LABOR UNIONS, AND STRIKES (1957–1964)

At the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s, in the context of growing social tensions and political struggles, workers were generally able to expand their space in the Brazilian public sphere. This was mainly true for (male) industrial workers in the cities and increasingly for rural workers in the countryside, but, as the example of the neighborhood associations illustrates, also included other groups of workers and the broader urban population. A nationalist, anti-imperialist rhetoric was powerfully articulated with a language of class that clamored for more inclusive economic development and deep social reforms in Brazil. Such political currents as the leftist nationalists and communists grew in the political scene. An overall picture that featured growing inflation, a wave of strikes, and protests characterized a period of intense political and social polarization that would come to a close with the military coup of 1964.

In that period, neighborhood organizations in São Paulo lived through a rapid process of radicalization and significant changes in the forms of action and political alliances in which they engaged. The year 1957 appears to have been a moment of particular importance for these changes. The SABs umbrella organization – the Federation of São Paulo Neighborhood Friends Societies (Federação das Sociedades Amigos de Bairros and Vilas de São Paulo, or FESAB), which had been created in 1954,Footnote 35 became stronger and began to act more consistently in conjunction with various other associations. For instance, in July of that year, a convention of SABs in São Paulo was organized, sponsored by the FESAB. Besides highlighting the accomplishments of the SABs so far, “in the sense of having achieved improvements in the general, immediate, or local order, such as: transportation, housing supply, water, illumination, sewage, pavement, mail delivery, telephone, public health, instruction, sports, etc.”, the convention demanded the right of these entities to participate in the “master plan of the city [...] and in the administration of the CMTC [Companhia Municipal de Transportes – Municipal Transportation Company]” and the formation of a “São Paulo metropolitan consumers’ cooperative” to ameliorate the problems of furnishing the city with basic supplies.Footnote 36

At the about the same time, the unions in São Paulo appear to have become increasingly attentive to the needs for workers beyond the shop floor and the need to organize workers in their neighborhoods. In a booming city like São Paulo, union leaders became ever more sensitive to the demands for urban improvements and increasingly sought strategies that accounted for urban geography. In the second half of the 1950s, various local unions, such as those of the chemical and metal workers, founded sub-headquarters in new neighborhoods with large concentrations of workers, as a way to bring unions closer to the laborers’ residences and, thus, to facilitate activism and worker participation in the running of these organizations.

At that juncture, one could also perceive a tightening of the bonds between neighborhood associations and the labor union movement. This was illustrated, for instance, by the presence of the former in a meeting called by the Inter-Union Unity Pact (Pacto de Unidade Intersindical, or PUI)Footnote 37 to debate the growing cost of living in São Paulo.Footnote 38 Joint actions not only began to occur more frequently, but these two movements also started to articulate a common agenda of demands. The subjects of their claims for urban improvements slowly penetrated the union agenda and some union members began to participate more actively in neighborhood organizations. This was the case, for example, for Santos Bobadilha, a well-known leader of the Union of Dairy Workers of São Paulo, who, in those years, became an active militant in the Jardim São Vicente Friends Society.

Figure 3 The so-called Strike of the 400,000 in 1957 was an important moment for the strengthening of the ties of unity between the SABs and trade-unions. Many picket lines were organized in the neighborhoods. Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo. Fundo Última Hora. Used by permission.

The so-called Strike of the 400,000, carried out in October of 1957, represents an important moment for the strengthening of the ties of unity between these organizations. It also brought about the emergence of a shared language and agenda between unions and neighborhood associations, which conceived workers also as residents of the city, and vice versa. Organized by a network of unions from various trades and industries, in particular the textile and metal industries, the strike, which took place at a moment when the economic plight of the poorer classes had caused widespread dissatisfaction, soon became a generalized labor action that paralyzed the whole city of São Paulo and other neighboring industrial cities. The movements took on the air of a popular rebellion: Picketing strikers took over the streets and several violent confrontations occurred in what is one of the most remarkable episodes in the labor history of São Paulo.Footnote 39 During this strike, the neighborhoods were one of the main locales that provided assistance for and sustained the work stoppage. Many picket lines, for instance, were organized in meetings convened in clubs and in residents’ organizations in the industrial districts. In the months leading up to the strike, many SABs positioned themselves in defense of workers’ rights and thus in favor of the unions’ position against the high cost of living. In the middle of the October strike, the alliance forged among residents’ associations and the union organizations of the city would be powerfully confirmed when FESAB released a manifesto expressing solidarity with workers, arguing that the “SABs are constituted in their absolute majority by workers from all industries and professions [...] and the struggle for a reduction in the cost of living is inherent in all of the people”.Footnote 40

The approximation between neighborhood-based movements and labor unions continued in the following years. In June 1958, a new meeting of FESAB, which already included 196 popular associations that had joined together, debated such old demands as the paving of streets in the urban periphery, but they also discussed the “formation of a common front of action, between the [neighborhood] entities, the Interunion Unity Pact, and the State Union of Students [União Estadual dos Estudantes]”.Footnote 41 Neighborhood problems and the demands of city dwellers were, in turn, increasingly discussed by union organizations, as in a meeting of the union of bank workers, in which union leaders and the SABs debated “the project of the city council member Norberto Mayer Filho concerning renewing the contract” of the Brazilian Telephone Company (Companhia Telefônica Brasileira).Footnote 42 Subjects like the problems of food supplies and cooperativism took an important place on the agendas of PUI meetings.Footnote 43

The spike in the cost of living was one of the main topics that united the neighborhood associations and unions. At the end of the 1950s, these entities jointly organized various protests against inflation, the loss of purchasing power as a result of low wages, and the ensuing impoverishment. In June 1959, for example, the labor attaché of the British Consulate reported on the preparations for a “hunger march” that would bring a caravan of “unionists, students, and members of neighborhood associations” to Rio de Janeiro (then still the national capital).Footnote 44 This growth of FESAB and of the neighborhood movement in São Paulo as well as their alliance with the unions worried the authorities to such a degree that, when the entity actively participated in the organization of a strike movement in December, the Ministry of Justice authored a law closing down the FESAB and other SABs for ninety days, although it was never put into effect.Footnote 45

In the effervescent period before the coup of 1964, the contacts and connections between neighborhood associations and unions appear to have deepened further. The importance of a kind of urban planning that was favorable to workers and poor urban residents in general began to take a more serious and important place on the union agenda. In July 1963, for example, some of the city’s main unions, like the bank, metal, and textile workers, signed a manifesto calling for urban reform as an important part of the “Basic Reforms Plan” proposed by the João Goulart administration. The overlapping interests between unionists, architects, and neighborhood organizations resulted in a seminar on the subject of housing and urban reform, which gathered a range of important actors from São Paulo’s civil society. The questions of housing, the problems that neighborhoods suffered, and the very question of urban planning as a whole came to be seen by unions as a part of the world of labor.Footnote 46 The coup that took place in April 1964, evidently, dealt a death blow to these incipient initiatives. Subsequent attempts to match interests or coordinate activities now had to take place under the conditions of dictatorship.

The experiences of the SABs and of São Paulo’s unions at the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s demonstrate a far greater political connection between the world of labor and urban questions than the older social science literature has generally recognized. For instance, in 1973, the sociologists Fernando Henrique Cardoso (later to become Brazil’s president), Cândido Procópio Ferreira, and Lúcio Kowaric emphasized that, in the 1950s and 1960s,

as a rule, the workers were absent from political life, at the level of urban demands. [...] The unions did not have the habit of [...] including in their programs questions connected to the urban problematic [...]. [At the same time], one cannot affirm that the Neighborhood Friends Societies represented workers. They represented much more the urban resident, a specific social category that the city created and whose action, during the process during which São Paulo became a major metropolis, attenuated if not completely dissolving class behavior.

Thus, the authors concluded, “the majority of the inhabitants of São Paulo remained politically marginal to municipal life”. José Álvaro Moisés, for his part, also considered that, “for a long time”, unions never demonstrated any interest “in the demands for urban living conditions for their members”.Footnote 47 Yet, as this article has shown, workers’ organizations and neighborhood organizations managed, at various moments, to unify their claims, transcending in practice the boundaries between the struggles in factories and in neighborhoods. In this process, a form of political action based on a much broader notion of class emerged, which included various dimensions of the lives of workers in São Paulo, in fact often overcoming the supposed division between worker and resident.

CONCLUSION

While the nexus between labor and urban issues has often not been fully acknowledged in a certain kind of sociological literature (in particular in the case of big metropoles in the Global South), labor historians have been more observant in highlighting the important role of working-class neighborhoods in the process of class formation during different periods and in various national contexts (though, here too, the focus has been on experiences in the Global North). In particular, in the context of large cities propelled by industrialization from the nineteenth century on, many have underscored the dense sociability of working-class districts as fundamental to the mitigation of multiple social divides and the construction of a class identity, as well as its role in generating support for collective action. In a famous article, Eric Hobsbawm, for example, called attention to the labor movement’s difficulties in large cities, “which are industrially very heterogeneous to have a unity based on labour” and “too broad to form true communities”. The “communitarian potential” of working-class neighborhoods, however, transcended this “inhospitable environment”, for it was here where “the true force of the working-class movement in megalopolises” resided.Footnote 48 Geoff Eley also reminds us that

workers of whatever kind led lives beyond the workplace […]. They lived in neighborhoods, residential concentrations, and forms of communities, cheek by jowl with other types of workers and alongside other social groups as well. […] They came from diverse regions and birthplaces, spoke different languages or dialects, and bore profoundly different cultural identities from religious upbringing and national origins. They were young people and mature adults, and of course women and men.

Thus, “the rise of the urban working-class neighborhood”, Eley argues, “was crucial” to the construction of a common working-class identity in Europe between the mid-nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth.Footnote 49

To emphasize the roles of neighborhoods in processes of class formation implies a more serious consideration of both the spatial dimension and of constructions of different senses of community in historical analysis. In this respect, the British sociologist Mike Savage points out, in considering the centrality of what he calls “structural insecurity” in the working-class experience, “it is as important to look at the coping strategies used in urban neighborhoods and within households as at the labour process itself”.Footnote 50

While the mentioned authors have offered valuable clues for understanding the interconnection between neighborhood communities, the workplace, and class identity, there also numerous accounts, especially in older or “classical” studies of class formation, that lack attention to these spatial dimensions. This absence was polemically highlighted in Roger V. Gould’s revisionist analysis of the famous Paris Commune of 1871. Gould asserts that the insurrection, contrary to the sacred mythology of the left, had little to do with class struggle and rather concerned the formation of communitarian urban identities in the context of the ongoing disputes over municipal freedoms, as opposed to the political centralization of France in the Second Empire.Footnote 51 David Harvey has refuted in minute detail both Gould’s historical research methodology and the conclusions he draws, emphasizing how, in a variety of historical contexts (such as in the case of the Paris Commune) “there were class identifications related to local places, neighborhoods, and even communities [...]. The signs of class and class consciousness are as important in the space in which people lived as they are in people’s work”. Thus, Harvey continues, neighborhood institutions are spaces of social solidarity that are perfectly compatible and linked with social relations of class. In the context of the urban transformations of Haussmann’s Paris, the city had “a community of class as well as a class of comunity” in Paris’s working-class neighborhoods.Footnote 52

Nonetheless, despite the intense debates and the evident weight of the mentioned discussions around working-class districts and their connections to class and communitarian identities, the international literature on these topics is very “parochial”, exhibiting an evident lack of transnational or even comparative studies of neighborhoods. Conversely, the burgeoning field of Global Labor History – which precisely calls for an inclusion of such perspectives – conspicuously lacks sensitivity for the spatiality of the local. There seems to be little space for “place” in these more recent approaches, with few studies of local organizations or neighborhood workers’ associations realized under their auspices.

One can outline some reasons for this absence. First, a significant part of Global Labor History appears to privilege a return to macro-narratives with an emphasis on economic processes on a global scale, with little interest in highly local studies, such as those at the neighborhood level. Second, a seeming lack of connections and transnationality between neighborhood associations confines their study to a level that, even within the municipal universe, can be considered “micro”, making a more global analysis of the phenomenon difficult or, indeed, impossible. Third, although Global Labor History also has broadened our understanding in both time and space of what labor constitutes and who workers are – going decidedly beyond the forms of wage labor predominant in the Northern Atlantic world from the nineteenth century on – one can still perceive the continuation of the old dichotomy and hierarchy between productive space and the spaces of social reproduction. The role that residential spaces and workers’ neighborhoods have played in global development of labor is still underestimated.

Meanwhile, neighborhood associations have, since the 1970s, constituted one of the central concerns in studies about the so-called new social movements. Heavily influenced by such authors as Jürgen Habermas, Alain Touraine, and Manuel Castells, among others, a large part of the academic work on this topic has almost entirely fallen to geographers, sociologists, and political scientists emphasizing the “newness” of movements emerging in the 1970s. Beyond the supposedly shared values across these movements – autonomy vis-à-vis the state and the traditional political forces (including the labor movement), democratic, and participatory internal organization, etc. – this “newness” was said to manifest itself also in the emergence of social identities with little or no relation to class identities or with the world of labor. Such views have contributed to a segregation of research fields, with the study of neighborhoods and of territorialized popular organizations remaining largely outside the domain of labor history.

Yet, the study of neighborhood associations in Brazil and in Latin America in general holds many promises for labor historiography, including for studies inspired by the ideas of Global Labor History. Two interesting examples might illustrate the potential for comparative and transnational analysis in the study of neighborhoods and local workers’ organizations.

The historiography of India, for instance, has been vigorously questioning the conventional notion that sees factories as spaces of change and modernity and neighborhoods as places of tradition and stasis, in particular those areas that are connected to their rural places of origin, to religion, and to caste. Numerous studies have been demonstrating how urban life at the neighborhood level, associated with the experience of places of work, continually redefined the rules of inclusion and exclusion established between the workers themselves. Neighborhoods also created feelings of belonging and emotional bonds, lending visibility to the workers and to a certain idea of common identity beyond traditional divisions. Workers’ connections to their residential locales created the conditions for the emergence of leaderships and local organizations that demanded improvements for their districts and often forged links with union politics.Footnote 53 As one can see, despite great differences in culture and historical context, there are interesting confluences in the construction of identities, the formation of organizations, and the making of collective action that unite the cases of neighborhoods in industrial cities in India and in Brazil. Research that takes into account the analysis of working-class neighborhoods beyond the local and the national has much to gain from understanding the processes and unexpected connections, even across long distances, particularly in countries that have gone through rapid and intense processes of urbanization, migration, and industrialization.

As previously stated, the great, industrialized urban centers of Latin America open up another and even more obvious possibility for comparative and transnational analyses, although labor historians have yet to tap adequately into this potential.Footnote 54 The example of Argentina is especially illustrative here. Just as in Brazil, a new generation of Argentine historians has recently been revisiting and adding new questions to the debate about urban popular associations in their county, particularly during the period during the rule of President Juan Perón (1946–1955).Footnote 55 A significant part of this literature contradicts the conventional vision, established in the 1980s, which saw the strong tendency to form associations at the neighborhood level in Buenos Aires in the 1930s (with the proliferation of neighborhood clubs, popular libraries, and sociedades de fomento Footnote 56 ) as an expression of the supposed fact that the lower classes had outgrown primordial organizational forms based on class and ethnicity, which predominated in Buenos Aires until the 1920s. For this reason, these scholars avoided the use of the notion of “workers” and consecrated the term “popular sectors” for the subaltern residents of Argentina’s capital. Implicit in these authors’ analysis was the idea that the political culture of the Perón era, from the 1940s, with its emphasis on the use of the plebiscite, on state power, and with its tendency to articulate a certain language of class, has put an end to this prior civic culture and destroyed its popular associations as spaces where citizens would experience and experiment with democratic processes.Footnote 57 Contrary to such views, numerous historians have, especially in the last fifteen years, rejected the radical separation between civil society and the state that is implicit in the vision outlined above, and have shown how the Peronist state opened up space for the articulation and re-articulation of various popular demands.

The case of São Paulo in the 1950s and 1960s equally suggests that the phenomenon of urban associations has played an important role in the construction of a language of rights and in workers’ political interaction with local authorities and with the municipality – and that this happened in a more complex manner than analyses emphasizing clientelistic logics have acknowledged. Examining this phenomenon allows us to observe a greater permeability and porosity of the state, which functioned as a site of conflicts and, under certain circumstances, was receptive to the demands from below, as was the case between the 1940s and the 1960s in Brazil. As this article has explained, a popular, neighborhood identity, on the one hand, and a laborer’s, working-class identity, on the other, are not mutually exclusive. Despite their socio-occupational heterogeneity, many neighborhoods in São Paulo recognized themselves and were recognized by others as “working-class”. “Popular”, “working-class”, and “resident” can be complementary identities and are not necessarily in conflict with each other.