Second thoughts emerged barely three months after the publication, on 10 March 1894, of the French executive decree on the mandatory aeration of workshops cleared of personnel during mealtimes. The Catholic weekly Le Dimanche pinpointed the rule's “somewhat embarrassing consequence, to wit: the removal of the workforce to the streets during lunch hour”.Footnote 1 No one contested the government's rationale to protect the health of workers on the job from air corrupted by dust, volatile particles, fumes, and stench, an argument that also animated reform movements in the English-speaking world and which gave rise to clean-air legislation in the British Factory Act of 1895.Footnote 2 There was enough evidence proving the efficiency of a vigorous, window-to-window ventilation to remove airborne contaminants from indoor spaces while channelling fresh air into worksites.Footnote 3 While the rule formed a partial solution to the toxicological risks workers encountered on the job across industries, it put an end to the long-established use of workspaces as eating places. It led to the spillover of lunching crowds into public places, where other dangers lurked: outdoors, these included the harassment of women, parks littered with leftovers, and flu due to chilly weather; indoors, restaurants threatened to foster alcoholism, to offer tainted food, and to lead to promiscuity with no assurance of a cleaner atmosphere. Of course, social and technical innovations come with the possibility of unforeseen upshots, so much so that sociologist Robert Merton outlined their causes in a classic article.Footnote 4 It launched a large literature on how to predict – and prevent – hazards of most every kind, and initiated myriad studies relating decisions to drawbacks and perverse effects. This inquiry adds another dimension to examinations of unforeseen outcomes. It explains how a series of often cross-purpose mobilizations ended with the decree's Articles 8 (evacuation of worksites during meals) and 9 (compulsory aeration during mealtimes) rendered more flexible within a decade. The ending was far from predictable. No one had anticipated that workers, much less women workers – the supposed beneficiaries of the sanitary measure – would campaign for the re-authorization of eating on the shop floor. This article explores the reasons why, and the means by which, they contested legislation whose aim it was to protect working people.

Collective action – retrieved here through union, police, and ministerial archives as well as government publications and the national and local press – clinched a victory in the struggle over the aeration rule. The paper's first section details workers’ low-key objections to the decree as it disrupted their daily lunch routine;Footnote 5 it mentions particular manufacturing sectors with continuous production processes (sugar refining, papermaking) that urged government to relax the regulation to assure uninterrupted, complete fabrication cycles. Section 2 sheds light on the protracted union-led strike in the Parisian sewing trades (4 February to 11 March 1901) as the “transformative event”Footnote 6 that quite surprisingly propelled the lunchtime issue from a circumscribed, discreet, and occasional presence to national prominence. The walk-out mobilized the seamstresses, and their union called for the rigorous implementation of Articles 8 and 9 to stop the fashion houses’ ploy of serving lunch on the shop floor to their strike-breaking female staff (employers in Chicago applied the same strategy during the 1910 garment workers’ strike).Footnote 7 This is thus also a story about gender and empowerment as dressmakers – just like the female workers in fish conservation, cheese making in Roquefort or the textile industry – no longer stood “timid and without resolution” in the shadow of their male colleagues with whom, as historians have noted, they shared claims for higher wages, an end to piece work and shorter work days.Footnote 8 Parisian seamstresses demonstrated their public clout and set a benchmark for future militancy.Footnote 9 The third section shows how the scrupulous application of the lunchtime regulation rekindled the resentment among the personnel of the heavily female fashion and artificial-flower industries. Their informal networks circulated petitions that urged authorities to relax the legal requirement to evacuate shops for aeration during lunchtime. One female labour inspector commented in her yearly report for 1901 that “the enforcement of Article 8 sets off strong emotions among women shop workers. The kind of protection appears tyrannical to the women and girls who, living far from their workplace, have taken up the habit of bringing in their already prepared lunch”.Footnote 10 Strict enforcement was the catalyst that rendered the objectionable intolerable.

Anxiety about women causing public disorder after the 1901 walk-out triggered the government's introduction of a slightly amended version of the 1894 decree that granted chief labour inspectors a degree of discretion in authorizing lunch on the shop floor. This is an interesting outcome. For one, authorities conflated two forms of women's mobilizations into a single threat to the ordinary, hum-drum run of things. These events were not only discrete, they also happened consecutively. Their motives diverged; in fact, the second episode (petitioning) was a reaction to the consequences of the first incident (strike). Historiography tends to identify such outpourings of collective verve separately, too. The first approach, which helps construe the seamstresses’ strike in 1901, situates the rallying drive with women's unions that strove for the recognition to engage in collective bargaining.Footnote 11 The second line of inquiry emphasizes the grassroots momentum in women's struggles and here sheds light on the petitioning women of Paris after the end of the work stoppage. Their claims grew out of a feminine rather than a feminist consciousness (to use Temma Kaplan's distinction), they couched their arguments in family terms around the defence of non-economic benefits of women's jobs, and the campaign built up from local, informal female networks that also existed elsewhere and sustained labour struggles as far apart as Barcelona, Shanghai, or Wheatland, California.Footnote 12 The lunch-break conflict of the early twentieth century most mattered to wage-earning women and, while issues of eating breaks for female workers came up here and there,Footnote 13 it appears as a typically French issue. To look at the process of its resolution is to do justice to the historical dynamic as well as to pay attention to the different stakeholders – from working women and men, to union members, labour inspectors, factory owners, politicians and even journalists.

Lunchtime and Hygienic Regulation

Reformers and legislators had worked for ten years on protective legislation before adopting the first law on workplace security and hygiene in 1893. It was part of a legal battery that formed the foundation of the welfare state (women's and children's employment in 1892, work accidents in 1898, a partial passage to the ten-hour work day in 1900, retirement benefits for workers and peasants in 1910, minimum salary for women in domestic textile sweat shops in 1915).Footnote 14 Preparatory drafts left no doubt about the motivation to ventilate the shop floor across industries during breaks. The idea was to “evacuate the micro particles and reduce the ‘animalization’ of the air”.Footnote 15 This was not new. The national assembly's advisory committee on industrial hygiene mentioned precedents from England, Denmark, Norway, and Switzerland to strengthen their case for similar, encompassing directives in France.Footnote 16

By the late nineteenth century, hygienists had established the aetiology of many an industrial disease (phosphorous necrosis, saturnism, silicosis, etc.).Footnote 17 Precautionary advice on occupational health was ubiquitous. Scientists insisted on a minimum volume of indoors space per worker and the necessary renewal of its air.Footnote 18 The Dictionnaire encyclopédique des sciences médicales urged to ventilate all confined work areas, and it advocated strict personal hygiene, including thorough handwashing before sitting down to a meal outside of workplaces where toxins (arsenic, lead, mercury, etc.) were handled.Footnote 19 There were reports on the poisoning of house painters who had not washed their hands before eating their finger-food lunch in enclosed work sites.Footnote 20 Jobs where women's employment was exclusive, predominant or important – washing, laundry-, flower- and match-making, sewing but also metal polishing – received the same advice, that is: eating in separate rooms after changing work blouses or aprons and washing hands under running water.Footnote 21

The architects of the 1894 decree devised a regulatory frame within which to formulate amendments and modifications in response to production constraints or changes in technology and shop-floor organization.Footnote 22 Employers were quick to point out the difficulties in implementing Articles 8 and 9. Their complaints went to the Labour Office and its tutelary ministry. Manufactures where humidity was important to the treatment of textile fibres, such as spinning, noted the impossibility of keeping the relatively moist atmosphere constant during aeration, a difficulty that also spurned owners’ opposition to ventilation in Massachusetts and Lancashire cotton mills.Footnote 23 Industries like sugar refining around Paris and in the North, and papermaking located in the east (Doubs, Jura) of France, insisted on the practical limits to the enforcement of the eating-break rule. Their production processes were continuous, depended on a steady supply of heat, and required constant supervision. One industry representative exclaimed that obliging workers in sugar factories to leave their workstations to grab a bite to eat is “like asking firefighters to quit a fire because it's lunchtime”. In 1901, a labour inspector from Brittany reported that “it is common practice among workers in around-the-clock processes to eat in the shop”.Footnote 24 Night work, it turned out, combined the problems. Machines needed running while opportunities to eat out in poorly lit neighbourhoods were few, if any. The labour inspector for north-eastern France remained matter-of-fact in noting that “workers in night crews eat while supervising the machines”.Footnote 25 Professional associations proposed amendments. They formulated organizational solutions. Shifts among alternating working teams offered one way to keep machinery running during meal breaks. Others counted on technological innovation in aeration, air-conditioning and exhaust ventilation to maintain the required atmosphere for production. Progress, however, seemed slow in coming, and pricey to boot.Footnote 26

Workers’ concerns owed little to technology and much to everyday subjects. Factory inspectors, whose task it was to implement labour laws, regularly reported on the special difficulty of enforcing “Art. 8 of the [10 March 1894] decree, which obliges workers to take their meals outside the workrooms. It should not raise any objection as hygienic considerations amply justify the measure. It instigates, however, some of the most important adversities.”Footnote 27 Historians have lined up a series of reasons to explain workers’ defiance of industrial hygiene: fear of losing autonomy on the job or of losing the job altogether, a certain attachment to routine, and ignorance although Janet Greenlees has found evidence that working women and men sized up “acceptable risks” in the workplace and responded to them within the constraints of keeping their livelihood. A gendered spin points to the veneration of virility and physical force as a factor accounting for men's relative indifference to the dangers at work.Footnote 28 While the ascription begs the question of women's attitudes towards danger in the workplace, it also edges past issues connected with the daily routine of workday lunch and its relation to the prevention of adverse health effects on the job.

Workers’ rejection of Articles 8 and 9 had roots in proximate motives of discontent. Cost and weather posed concrete limits to a modification of lunch practices. Habit (or preferences) and a certain form of self-respect (amour propre) – the capacity to decide for oneself – subsumed more intangible drives to resist. So much was obvious a year after the decree had gone into effect. The chief labour inspector of the Paris area lamented the poor welcome that the new legal frame had received from the labour force. He went on to write that

[T]hose whose residence is quite distant from the factory, and who bring in their lunch, declare that the decree forces them either to eat in the street or to go to a restaurant and spend money. The objection is even stronger when made on behalf of women and children. […] Some industrialists, concerned with the well-being of their personnel, have built refectories. At one place after two days, the working women absolutely refused to use it for reasons of amour propre.Footnote 29

The injunction to ventilate workspaces to chase away harmful substances during breaks appeared like an unproblematic measure to protect workers’ health. In theory, the recommendation seemed all the more feasible as eating facilities appeared numerous.Footnote 30 Choice, of course, is not merely a question of options. Opportunities come with a price tag. Physiologists calculated that a calorie eaten away from home was twice as expensive as its homemade equivalent.Footnote 31 Sit-down meals in commercial eateries were expensive. And they weighed more heavily on working-class women. A full commercial lunch absorbed almost thirty per cent of their average daily wage. Men spent about twenty per cent of their daily pay on a proper meal.Footnote 32 In other words, Articles 8 and 9 came with a cost. Their economic impact was one of the reasons for workers’ dissatisfaction.

The persistence of lunchtime routines was patent. Workers stuck to taking lunch in their shops and factories as it was, according to Jacques, chief labour inspector of the eastern circumscription, “very hard to modify long-established habits”.Footnote 33 Such inertia posed a problem to the Labour Office. The government made the resolute application of Article 8 a priority. The principle, however, suffered amends. The executive went so far as to afford a margin to the labour inspectors, urging them to see that the regulation “be applied as strictly as possible”.Footnote 34 The expression became something of a mantra. Early on, the chief labour inspector of the north-eastern circumscription observed that “the many reclamations [concerning the decree of March 1894] have incited the labour inspectors to adopt a posture of great tolerance and to limit themselves to giving only such advice that would get them as close as possible to the spirit of the law”. His colleague in the central circumscription noted in 1896 that “factory owners have taken our observations into account within the limits of what is possible”.Footnote 35

The possible required time. The law and sanitary prescriptions were ideals to reach, the head of the south-eastern circumscription Blaise stated, and patience was the best way to get there. To force issues was counterproductive. He declared “tolerance is indispensable even though it needs to be transitory”. In 1897, a district labour inspector urged his hierarchy to push for an easing of Articles 8 and 9. He said that “formal summons remain without results”. Workers, he reported, continued to eat in their workspaces, a practice that corresponded to everybody's expectation. He suggested the adaptation of the law to specific industries, leaving no doubt on the law's justification with regard to manufactures where toxins entered the production process. Where possible, however, he advocated to grant workers the same latitude as before the decree of 1894 so as to avoid disaffection and conflict. The idea was widely shared. It combined, another labour inspector declared, “patience and resolve in the search for small steps forward”.Footnote 36 The compass of moderate but steady progress could have continued to guide the Labour Office's approach to implementing the regulation. A strike triggered a change in the politics as usual.

The Spark: Striking Women

Legislative reform originated with the 1901 strike that saw women's tailors fight for better wages, an eight-hour day, and the abolition of piece work. The month-long walk out – it lasted from 4 February to 11 March – failed to achieve its goals. A united front of intransigent employers faced down the movement with a lock-out.Footnote 37 And yet, a convoluted subplot with its own unexpected consequences involving the seamstresses employed by high-fashion houses breathed new life into the lunch-break issue. To be sure, this “transformative conflict” to put Articles 8 and 9 upfront on the public agenda was unlike the mobilizations singled out in Sellers and Melling's programmatic review of clashes over workplace dangers. The law emerged as a surprise. Rather than highlighting its relevance to toxic outputs in production and to the harm they inflicted on workers’ health in the long run, women workers wielded it as a tactical device to force the hand of their employers during the strike.Footnote 38

The tailors invited the seamstresses to join their movement on the eve of their strike.Footnote 39 It took more than a week and several other pleas to convince the female dressmakers. As in so many places, misogyny in labour unions likely explained women's initial misgivings.Footnote 40 They eventually joined the movement by February 11 “after overcoming the hesitations of the first hour”.Footnote 41 They did so on the condition “that there be reciprocity, that the men support the ladies’ demands”.Footnote 42 Female strikers, who demanded the meticulous construction of the law as a weapon against abusive employers, received union backing. The seamstresses’ union dated its earliest activities to 1892, counted 500 adherents on the eve of the 1901 strike, and relied on a core of sixty active members to sustain day-to-day militancy. This was part of the increase in women's union activism.Footnote 43 While men's support helped women to voice their claims in public, the invitation to join the strike was as much a gesture of inclusion as of interest.

Working-class solidarity was not a foregone conclusion. While the sewing trades offered many jobs to immigrants,Footnote 44 hard times tended to pit ethnic groups but also tailors and seamstresses against each other. There were about 800 tailors for women and about 20,000 high-fashion modistes and seamstresses working in Paris. While skills defined the occupational hierarchy in fashion houses, women needle-workers could grab opportunities and change job venues in response to the vicissitudes of the economy.Footnote 45 This gave rise to competition between women and men in the fashion industry. A police report noted that owners in the trade took advantage of the antagonism by relying on women as strike-breakers. The tailors’ walkout had prompted counter-tactics, the informant wrote, “as many high-end fashion houses organize shops where women do the same work as the tailors”.Footnote 46 Women's participation in public meetings at the union-led Labour Exchange overcame the opposition of the sexes at the high end of the textile industry's labour market.

The joint movement of the seamstresses and women's tailors was so sensational that it received regular mention in newspapers and police reports. In fact, just as in female strikes elsewhere, there was a joyous, almost carnivalesque aspect to the seamstresses’ public movement.Footnote 47 Women often accounted for half of the attendance in public meetings. Their presence added, according to cultural critique Arsène Alexandre, “a festive element to the happenings even though the tragic problem [of misery] is never far off”.Footnote 48 On 20 February, they were 600 in a 1200-strong meeting whose main resolution was a rebuttal of media accusations that peddled the mistaken affirmation of women's subordinate role in the tailors’ campaign.Footnote 49 But seamstresses inclined less towards a walk-out. While the strike of tailors for women mobilized 600 men throughout (seventy-five per cent of the professional group) and united fifty-five employers out of roughly 100 against them, women's walkouts were fewer, targeted specific fashion houses, and with one exception mobilized a smaller fraction – from one tenth to one third – of their staff.Footnote 50

The seamstresses were now in the news. They no longer lived by the norm of female quiescence and docility in the public sphere. And it showed. The weekend supplement of the Petit Parisien of 3 March 1901, which sold one million daily copies, carried a colour print of a meeting of tailors and seamstresses on its front page (see Figure 1). The commentary said that “the affluence was considerable”.Footnote 51 The seamstresses’ putative coquetry revealed itself as an element of respectability. Le Socialiste mocked the bourgeois papers “stupefied by the curious spectacle of well-dressed tailors and, above all, the seamstresses of cutting-edge fashion houses”. Their chic dresses distinguished them from miners or masons, the newspaper wrote, “they are nonetheless exploited like the others. Elegant and beautiful female citizens [citoyennes] speak up at the Labour Exchange, and their resolve transports the cause of the proletariat”.Footnote 52 The left-leaning Estafette scoffed at the “journalistic or doctoral feminism that will never end abuses”, and saluted the seamstresses’ movement as “the will to free themselves from intolerable despotism and limitless exploitation”.Footnote 53 The press eagerly reported on the strike, the dreaded police prefect Lépine took a particular interest in it, undercover agents spied on it, and the police occasionally – but just as elsewhere – used excessive force against it.Footnote 54 In short, there was a palpable sense of disorder that haunted the authorities in the face of women's mobilization. Its memory was to mark the future.

Figure 1. Striking women. Fashionable dress emphasized the respectability of the seamstresses’ claims for better wages, fewer hours, the abolition of piece work, and the right to convenient eating places. According to observers, women's participation in collective action added a joyous element to serious concerns. Le Petit Parisien. Supplément littéraire illustré, 3 March 1901.

While seamstresses made very similar claims as their male counterparts (an eight-hour-day paid six francs and the abolition of piece work),Footnote 55 a specific plea concerning the organization of the working day set women's requests apart from men's goals in the strike. They wanted “the installation of refectories so that the seamstresses are not obliged to eat on the stairways or outdoors exposed to all winds”.Footnote 56 It is impossible to ascertain whether the demand was part of a wish list prepared on the eve of the mobilization. At the International Congress on the Condition and Rights of Women in 1900, the feminist editor Marguerite Durand had floated the suggestion of putting an end to seamstresses’ eating in improvised spaces while ventilating their workplaces, and the bourgeois advocacy group Ligue sociale d'Acheteurs urged consumers to patronize shops with lunching facilities for their workers.Footnote 57 The idea of refectories was thus in the Parisian air, and the strike launched it on a surprising path.

To obstruct their workers’ mobilization, the owners of various fashion houses, among which the prestigious Beer, Paquin, Redfern, and Worth, offered several hundred lunches to their non-striking employees. They aimed at avoiding any encounter between their staff and picketers at noon. Critical comments coming from union sources accused employers of sequestering their personnel to prevent them from joining the walkout.Footnote 58 The action incited socialist assemblyman Viviani to remind a 3500-strong meeting of the manoeuvre's illegality in light of Article 8 of the 10 March 1894 decree.Footnote 59 The assembly swiftly dispatched a delegation to Alexandre Millerand, minister of Commerce and Industry, to hasten the application of the law. Millerand, the first socialist in government, was a signal presence at the top of the state in that he communicated a constructive attitude towards workers’ concerns; he kept an eye on the regulation of industrial poisons and backed the extension of the 1893 law on hygiene and security in the workplace to non-mechanical occupations like restaurant cooks or office clerks.Footnote 60 He sent labour inspectors to check the mealtime set-up. They found that “a number of employers have indeed served meals to their seamstresses, not in shops but in especially prepared rooms. The workshops have been ventilated, so that the inspectors found no violation of the extant regulation”.Footnote 61 The minister's delayed enforcement of a law “so important to a great number of women” astonished the strikers but they were, according to an article in Durand's daily La Fronde, satisfied to have set implementation in motion. Pressure proved the mother of invention, and it showed that practical solutions to respect the law were at hand.Footnote 62

The Pendulum Swings Back: The Grassroots Campaign

The strike of the tailors and seamstresses had unexpectedly given new salience to Articles 8 and 9. Labour inspectors seemed to take their cue from the newfound attention and ministerial mandate. While infractions of the March 1894 decree increased by twenty per cent between 1900 and 1901, penalties inflicted for the violation of the paragraphs prohibiting lunch at work rose by seventy per cent from 290 instances to 501.Footnote 63 Whatever the situation was during the strike, the zeal to have the letter of the law respected irked certain categories of workers. Now the pendulum of activism swung back to a campaign in favour of a more tolerant enforcement.

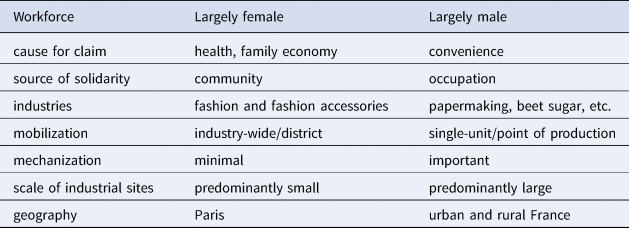

The new context breathed fresh, vigorous life into old arguments. The vast majority of workers’ claims to uphold the right of eating in the worksite expressed concrete concerns. Gender operated as a dividing mechanism in the attempt to reform Articles 8 and 9 (see Table 1).

Table 1 Gender and claims to relax lunch regulations, 1901–1904.

Women and men hailed from different occupational backgrounds. Men's cases originated in industrial jobs (textiles, printing, ironworks) located in many regions. Conveniences like shelter from inclement weather and distance from work figured prominently in their contentions.Footnote 64 Women's demands came from the smaller but heavily female and often quite seasonal craft shops of the Parisian manufacturing sector (sewing, ornamental feathers, artificial flowers). Women relied on personal relationships to lobby for their cause. While their claims highlighted the impact of Article 8 on female health and finances, they also hinted at the moral implications of sending women into the streets and commercial eateries at lunch hour. Women workers understood, and agreed with, the health concerns conveyed in the rules about aeration; they often put forth the sufficient number of cubic feet per person in the shops. They said, however, that the directive added to their existing financial burden, noting that

We can bring in healthy food cooked in our families. It would be unjust to compel us to take our meals in holes-in-the-wall [gargotes] where there is less air than in our shop and where the food is adulterated and more expensive [than the lunch basket].Footnote 65

While men continued to campaign on a single-site based mode, coordination was obtained among women workers. The movement gathered momentum as more workshops joined in. Short distances and geographic concentration helped. Feather workers signed a petition. They explained the difficulty to make ends meet on their modest salaries, which kept restaurant lunches out of their reach (their employers had no rooms reserved exclusively for breaks).Footnote 66 Flower-makers insisted that homemade meals realized savings to benefit the entire household. They added, “we are mostly young women who do not care at all to lunch in restaurants where, very often, we confront the obsessions of people who absolutely lack manners and respect”. The contention resonated with others who insisted on the familial ambiance in shops when compared to the motley and at times predatory clientele in restaurants.Footnote 67

The family motive mobilized beyond the workshop itself. Ferdinand Buisson, assemblyman from a working-class neighbourhood in Paris, received a letter from a father who detailed the conditions in which “his daughter and thousands of women workers [in the so-called Parisian industries] were compelled to take their meals in the open air”. In fact, a letter-writing campaign from his constituency prompted Buisson to invite the Minister of Commerce and Industry to study the feasibility of derogations to Article 8 in order to preserve everyday arrangements that, as historians Perrot and DeVault have argued, facilitated women's gainful employment.Footnote 68 Surprisingly, the correspondents did not press for higher wages. It was left to the Labour Commission of the Seine department (which included Paris) to suggest a trade-off between the construction of refectories and a rise in women's wages.Footnote 69

Notwithstanding Louise Tilly's contention that petitioning women achieved little success,Footnote 70 their arguments in favour of a broader interpretation of lunchtime regulation resonated with authorities and the press. In a letter to the Prime Minister, Minister Trouillot explained that the “very large number of reclamations” with respect to the prohibition of eating in work spaces had convinced him of the relevance of adjustments.Footnote 71 As it were, the artificial-flower makers’ professional journal construed the presence of machinery as a condition for labour laws to apply. It accordingly announced that flower-makers, who were dexterous manual workers with little technical equipment, had the right to eat in their shops.Footnote 72 Such claims drew on the continued reporting on working women's demands in the printed press. A year after the strike, the centre-right daily L’Éclair ran a long commentary on the “good intentions behind Article 8”, only to find fault with “these labour laws that risk to harm precisely those interests the lawmakers pride themselves on defending”. It enumerated the regulation's unanticipated consequences, and deemed Article 8 too severe, its dispositions “causing profound perturbations in women's proletarian life”. It concluded with a call to withdraw the paragraph from the 1894 decree.Footnote 73

While the government mulled over a possible reform, frenzied if behind-the-scenes happenings uncover the tight spot from which authorities had to act. It pertained to labour trouble. The memory of the 1901 strike got revived when, on 11 September 1902, the renowned Maison Beer decided strictly to carry out Article 8.Footnote 74 The aeration of the workshop required the evacuation of all the personnel whose number exceeded 200 operatives in a five-storey building. The seamstresses, some of whom probably remembered their employer's strike-breaking resolve in early 1901 (Beer had offered lunch to seamstresses during the collective action), deemed the action inacceptable. They opposed the enforcement and insisted on the continued tolerance of the practice of eating in the workplace. The Police Prefect of Paris informed the Chief Labour Inspector in the evening that his men had observed an unusual effervescence in the garment district. Their observations pointed towards a movement involving the employees of several fashion houses in the neighbourhood, as a result of which “a thousand seamstresses will likely remain standing on the sidewalks in front of their employers at noon on Friday and the following days”. The garment workers’ militancy sent tremors through the police. The chief law-enforcement officer asked the Labour Office “to take measures to prevent this protest rally”. In some sense, legal time got suspended. The government would not sanction Beer for letting his personnel lunch in the shop, especially since it planned to revise Articles 8 and 9. The short term was, however, much more important. The news of the improvised solution that allowed lunch in the shops spread through the high-fashion district, Laporte noted, “and the dreaded crowds did not form”.Footnote 75 The stealthy manoeuvre had defused tensions. No women stationed on the pavement. Tolerance prevailed until the modified regulation was to go into effect in 1904.

In the meantime, the minister instructed the Labour Office “to facilitate, by way of transitory arrangements, the application of the regulatory prescriptions in companies where their rigorous enforcement could have troubled the operations of the industry or the habits of the personnel”. While legislation was being rewritten, a “Note” from the Labour Office ordered inspectors to refrain from giving fines to shops without obvious health hazards.Footnote 76 The message got through. The rule of thumb to prevail in the period before revised regulations provided new legal bearings was to let people take lunch in their immediate working environment.Footnote 77

After the women's strike the government put two standing advisory committees to work towards the revision of Articles 8 and 9 in 1902. Both went along with the pragmatic modus operandi. The Committee on Public Hygiene advised to relax the code.Footnote 78 The Committee on Arts and Manufactures corroborated the justification of reclamations, and advocated an easing of the rules that would give labour inspectors the authority of assessing hygienic conditions in shops and of okaying lunch at workstations.Footnote 79 The minister in charge of the file, Georges Trouillot, adopted precisely that language when explaining the reasons for updating the regulation in August 1904.Footnote 80 The new decree dated from 29 November 1904. Article 8 received the most important make-over (most other modifications helped streamline the regulation, none refined it). It maintained the principled ruling that prohibited eating in the workspace but authorized it, after investigation by the labour office, when three conditions were united: the absence of toxic substances in the workspace; a production process that did not emit noxious gases or generate dust; and satisfying sanitary conditions all around.Footnote 81 Flexibility was built into these guidelines.

Conclusion

The revision of Articles 8 and 9 showcased the responsiveness of the republic's political institutions to claim-making from the street. The process leading up to the loosening of the legal rules mandating the evacuation of worksites during lunch for thorough aeration to renew the atmosphere allows historical analysis to use the law as a prism through which to shed light on the framing of a hygienic problem in the workplace and on its reception in the world of work. Workers’ opposition arose because, to apply Merton's vocabulary, the legislators ignored the economic cost and practical strains that the well-intentioned directive on ventilation during lunch hour inflicted on them. Although there is evidence that workers appraised workplace hazards and accommodated risks when it came to air quality, the failure to anticipate the measure's burden heightens our perception of their overriding concern for expedients that simplified everyday life and diminishes the visibility of their anticipation of longer-term health benefits.Footnote 82

The legal obligation to evacuate and ventilate shops and factories during lunch eased but did not, by far, eliminate workplace hazards due to dust, smoke, and micro particles. Note that separate eating rooms for workers had their advocates elsewhere so as to diminish exposure to toxic substances.Footnote 83 But industrial canteens did not, initially, prove popular among workers in Europe because, as one labour inspector put it, they “smell of discipline, and it is for that precise reason that the worker does not like [them]”.Footnote 84 This being said, it was only in France that the regulation – enacted through Articles 8 and 9 of the 10 March 1894 executive decree – became a countrywide bone of contention between workers and employers, so much so that it sent ripples through the national political arena for an entire decade before authorities came up with a pragmatic solution to calm industrial and labour relations. It quelled the agitation among the seamstresses and nudged employers towards the installation of refectories at least, canteens at best. While the law thus sustained the extension of eating facilities, it helped but did not entirely prevent conflicts. Even after 1904, disagreements between workers, employers and labour inspectors flared up and required arbitrages.Footnote 85

While the 1894 decree sent male and female workers grumbling because it upset everyday routines, the decade-long agitation offers a good vantage point on the question of gender and collective action. Women and men shared workplace issues of wages, hours of work and the abolition of piece work in the 1901 union-led strike, a drawn-out movement that confirms French historiography on the importance of workers’ organizations to industrial activism. The seamstresses’ mobilization showed that class solidarity could overcome labour-market rivalries between women and men in the fashion industry. Eating on the job, however, emerged as an item that mostly stirred the seamstresses’ union. In the short run, organized female militancy turned the law into a weapon against employers who fed strike breakers on the shop floors of their fashion houses. In the long run, the strict legal application ignited women's petitioning operation to temper the regulation on the sanitary use of mealtimes for the aeration of workspaces. The women's campaign had its roots in everyday concerns and connections. No union appeared to have contributed to its organization. This is an overlooked aspect of women's contribution to French politics and labour relations. The contrapuntal claim-making with respect to the settings in which to take the midday meal notwithstanding, authorities did not distinguish workplace and quotidian motives of women's mobilization. Their alarm over women's renewed manifestation in 1902 disclosed that fear of working women's taking again to the streets fuelled the revision of the clean-air article.

There is another point to ponder. In spite of changing contexts and demands, health concerns took second place before, during and after the strike. The reduction of daily hassles before 1901 and, afterwards, the need for jobs and salaries to make ends meet eclipsed the apprehensions of operatives when it came to the risks linked to a hazardous eating and working environment. During the walk-out, physical well-being receded behind the union's tactical calculations to denounce the illegal behaviour of owners when serving an indoor lunch to their non-striking personnel on the premises. Parisian employers, by the way, remained quite inconspicuous over the decade-long conflict. They wished to keep fashion and allied industries running with as little regulatory interference as possible.Footnote 86 While women workers tried to cope with daily constraints, the employers’ pursuit of profit in the short run trumped any longer-term perspective of workers’ health and well-being.

This is not to gainsay the sanitary progress introduced with Articles 8 and 9. After all, the regulation applied throughout the twentieth century during which legislators occasionally updated it and labour conflicts tested it through the early 1960s when the law mandated canteens for companies with a workforce of more than fifty people.Footnote 87 French workers and employees, two thirds of whom regularly take their sit-down workday lunch in a built environment in the company of colleagues away from the job, discovered the decree's very existence in February 2021 when the government temporarily suspended it as a means to prevent the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic in restaurants and canteens. The provisional relaxation exposed not only the public's widespread unawareness of the law (which it respected quite unwittingly) and the lack of knowledge about its hygienic origins, it also demonstrated how much law and food culture actually converged and indeed reinforced each other over time.Footnote 88