We can safely assume that from 1500 to 1650 much of the world's population worked to earn their living. Though we know roughly what kind of tasks people performed, we know surprisingly little about their perception of work. This Special Issue aims to present the first inventory of its kind of prevailing attitudes towards work and of how work was valued in what is termed for some, but not all, parts of the world the early modern period. Our aim is inspired largely by a long-term project being conducted at the IISH: The Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations, 1500–2000. That project endeavours to establish a quantitative overview of labour relations worldwide for the period 1500 to 2000. Within the framework of that project the members of the Collaboratory collect data on labour relations for the years 1500, 1650, 1800, 1900, and 2000, thereby enabling shifts in labour relations to be identified. Those shifts and their interconnectedness will subsequently be analysed and explained.

The early cross-section years – 1500 and 1650 – are part of a crucial period in which a polycentric world became globally interlinked by large-scale circulations of people, ideas, and commodities. Since demographic and occupational statistics for these years are based chiefly on rough estimates, a more qualitative approach to attitudes towards work and the valuation of work in these periods is important for interpreting and understanding the statistical data and estimates collated. These attitudes and valuations differed from region to region and changed over time; such changes point to shifts in labour relations globally.

Work and its perceptions in historiography

In their recent volume The Idea of Work in Europe from Antiquity to Modern Times, the editors Catharina Lis and Josef Ehmer observe that little systematic work has been carried out on the development of work ethics in pre-industrial Europe. As a consequence, a standard narrative – leaning heavily on Max Weber – of a linear development, from a work ethic based on sixteenth-century Christian values to a work ethic rooted in capitalist culture and directed towards success, remains largely undisputed.Footnote 1 Such a perspective not only neglects variant views on work in earlier periods, it also lacks a differentiated linear narrative, which, moreover, remains too narrowly focused on the perspective of the “Rise of the West”. In a critical overview of the literature on the influence of Christian religion on work ethics, Lis and Ehmer explain that the idea of a distinct shift from the sixteenth century onward is misleading. They stress the continuity of religious attitudes to work in both Catholicism and Protestantism, implying on the one hand that work meant pain and toil in succession to Christ's suffering, and on the other that manual work meant serving God and one's community and was thus to be valued.Footnote 2

Since the late Middle Ages, labour discourse became influenced by political and social theories. The debate was no longer confined to monastic scholars, but was taken up by larger social groups. Lis and Ehmer explain the reasons for this intensification of the discourse and the greater esteem attributed to work largely in terms of socio-economic change.Footnote 3 They claim that an increase in wage labour led to an increase in labour discourse.Footnote 4 Lis and Ehmer argue that the next major shift occurred in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when the discourse on labour was disseminated even more widely and became influenced by philosophers.Footnote 5 Work was now considered “work for the nation”, forming the foundation of “national wealth”. In central Europe this was understood to mean working for the state.Footnote 6

For the purpose of the Global Collaboratory, the explanation of the connection between shifts in labour relations on the one hand and shifts in perceptions of work on the other is fundamental, and it is for this reason that the authors of this volume owe much in the way of inspiration to the book edited by Ehmer and Lis. Other influential studies on the concept of work in European conceptual history can be traced to the impressive pioneering work of Herbert Applebaum, The Concept of Work: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern (Albany, NY, 1992), which described and analysed trends and tendencies from antiquity to the industrial age.

In an earlier publication, the same author had already addressed the subject of work from an anthropological perspective. His edited volume, Work in Non-Market and Transitional Societies collected essays on work organization among hunters and gatherers in pastoralist societies, among cultivators and gardeners in villages, and in cultures and societies where non-market and market-oriented work values underwent change and adaptation. These studies discuss mostly contemporary, non-European cases. In his categorization of work in non-market societies, Applebaum defines work as embedded in the total cultural fabric, with strong communal aspects that involve mutuality and reciprocal exchange, aimed mostly at subsistence; furthermore, that work was not highly specialized, and was task-oriented rather than time-oriented.Footnote 7 The transition from non-market to market societies is important in this project as well, and many of the qualifications Applebaum made for the present can be found in our contributions, especially the changing role of reciprocity, the shift from task to time orientation, and the changing relationships between women's work and men's work.

While Applebaum treated Europe and many non-European regions and communities separately, other historians have focused on both. Michel Cartier's edited volume Le Travail et ses représentations stands in the tradition of Maurice Godelier,Footnote 8 which has a strong anthropological and linguistic focus. The case studies in Cartier's volume discuss extra-European communities from the eighteenth century to the present, with the exception of the editor's own field of research, China, for which he offered a perspective on work in antiquity.Footnote 9

More recently, Jürgen Kocka and Manfred Bierwisch have separately edited collections of articles on the history of work.Footnote 10 Both share a concern with contemporary changes in work, the decrease in the dominance of wage labour, and the diminished long-term commitment on the part of employers. Both collections link up to periods when dependent wage labour was not the norm, and they also look to extra-European regions for patterns of work organization that diverged from the western European case. They do so for reasons of contrast in a situation where the West is in crisis rather than in the ascendant. As for the European historical experience, both continue to convey the standard narrative. In their introduction, Jürgen Kocka and Claus Offe stress various factors that promoted the rise of capitalism: Christianity, especially Protestant work ethics, the discipline imposed on urban citizens, and the philosophy of the Enlightenment.Footnote 11 The non-European cases they present, from India, Japan, Malaya, Africa, and the Islamic world, cover mostly the present and can also be understood as contrasting with the European, or to be more precise, the German case.

The intention of these volumes is to explain the current occupational crisis in Europe and to offer suggestions for “therapy”,Footnote 12 or to propose a new orientation for the relationship between work and life.Footnote 13 Bierwisch's collection does not intend to provide new details, but to offer overviews of work in European antiquity, work organization in twentieth-century industrial Russia and its rural roots, conceptual aspects of work in China from antiquity to the present, work in Islam, and a case study of conceptions of work in a present-day African rural community.Footnote 14

As Lis and Ehmer have remarked, until now there has been no systematic treatment of perceptions of labour,Footnote 15 which makes comparison over time and space a complicated and risky undertaking. In view of this state of the field, the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations has aimed at synchronic observation in order to achieve a more coherent approach.

A new conceptualization of global labour relations

In the past decade a new and global approach to labour history has been developed, stressing the global development of labour and labour relations over a long time span. Global labour history as developed by the IISH is not a theory but a field of research. It concerns the history of all those people who, through their work, have built our modern world – not only wage labourers, but also chattel slaves, sharecroppers, housewives, the self-employed, and many other groups. It focuses on the labour relations of these people, as individuals but also as members of households, networks, and other contexts. Global labour history covers the past five centuries and, in principle, all continents. It compares developments in several parts of the world and attempts to reveal intercontinental connections and interactions.

To capture labour relations worldwide over a period of five centuries, labour needs to be defined broadly. Following Tilly and Tilly's definition,Footnote 16 the Global Collaboratory project considers as work “any human activities adding use value to goods and services”. This is a far more encompassing concept than the “gainful workers” or “economically active” that appear in the statistics of later eras, mostly starting from the nineteenth century, but compiled mainly for the twentieth. It takes account of the unpaid, mostly household-based labour of more or less all family members, including women and children, who are physically able to work. It also comprises all types of labour relations, from slavery to independent entrepreneurship and everything in between.

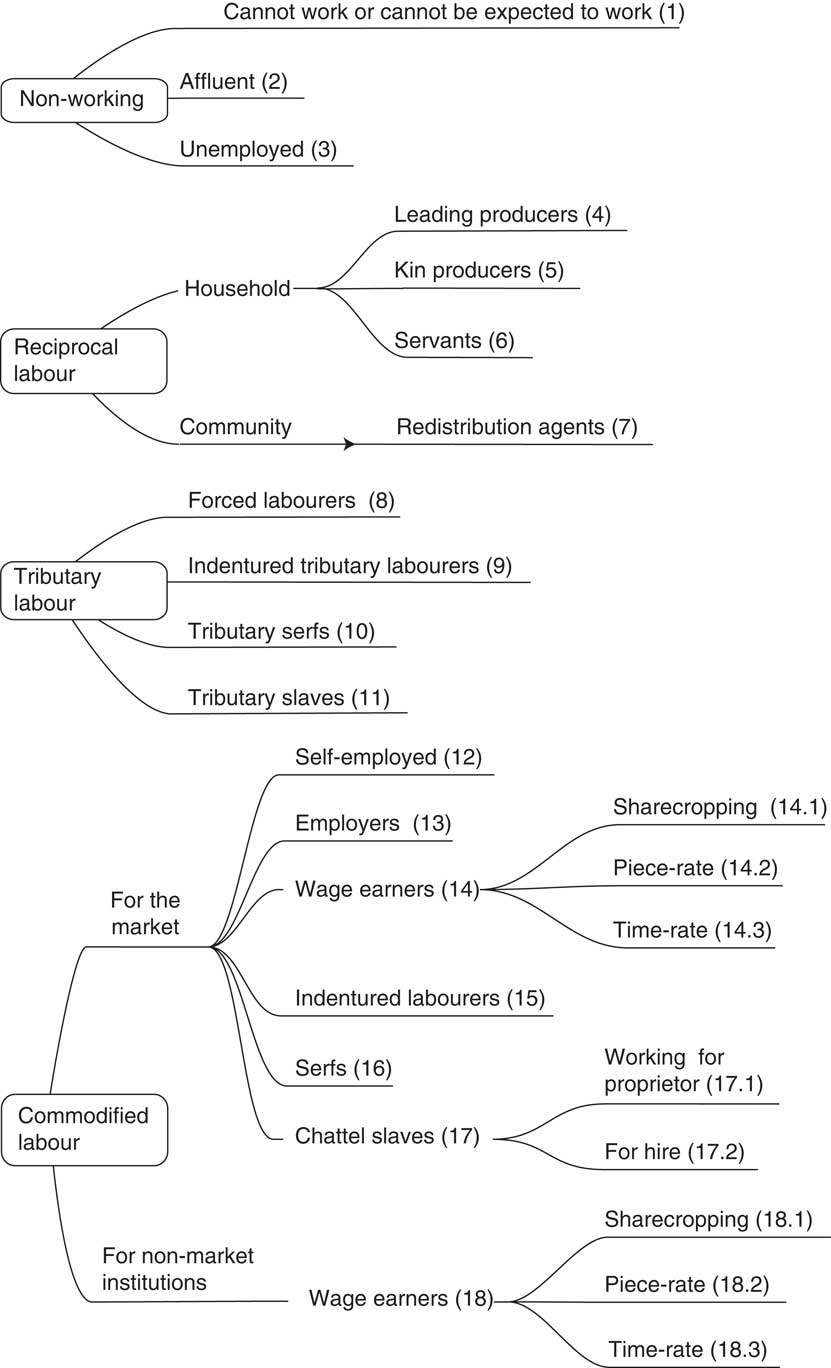

To systematize our approach, the members of the Collaboratory have developed a taxonomy of labour relations, based on four large categories: the non-working population and people either performing reciprocal, tributary, or commodified labour. These main categories focus on the target unit for what workers produce (be it goods or services); this can be either the household or community, the state or the market. In principle, we can classify the entire population using these main categories, which are subdivided into categories based on the level of dependency and degree of freedom, or lack of it. Any classification must of course leave room for intermediary stages and combinations of labour relations. (For our taxonomy of labour relations see Figure 1; for the definitions see Appendix.)

Figure 1 Taxonomy constructed by the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations. See Appendix for detailed descriptions.

For a number of regions, sources of information are available on the labour relations of at least part of the population in the early period, 1500–1650. However, our extrapolations and guestimates need to be confirmed by qualitative data. Knowing how people valued different types of work and labour relations helps us to interpret the scarce numeric data. In our search for perceptions of work, we wanted to look specifically at the concepts of work held by the majority of people, most of whom in the period 1500–1650 were working in agriculture, housekeeping, or subsistence labour but who have not left any written traces. This proved to be very difficult, as there are few sources that yield information about the perceptions of the workers themselves, and those that do exist are hard to date. However, the work people actually performed can tell us something about their valuation of work. If images depict working women and children even though normative texts disapprove of such work, we can assume that women worked if it was opportune and necessary to do so.

Perspectives on work ethics, norms, valuations, and ideologies

To further systematize our approach, we introduced a set of seven perspectives to describe and analyse early modern work ethics. First, we asked the authors to identify texts or other expressions and traditions that deal with work ethics, norms, and valuations. Secondly, we wondered whether changes over time in the appreciation or disdain of work could be reflected in socio-linguistic perspectives. What terms and concepts were associated with “work” and “worker”? Thirdly, the authors were asked to ponder the question of the position of work and worker in society. In particular, how was wage labour as a kind of commodified labour perceived in comparison with other labour relations? A fourth set of questions concerns free and unfree labour. It is included in the taxonomy but transcends the four main categories since it occurs in reciprocal household labour, in tributary labour for states and polities, and in market-based, commodified labour. One important perspective is therefore the valuation of free labour and the legitimation of unfree labour. The fifth issue relates to the motives behind the rankings of particular occupations. Criteria on the negative side include the physical strain, or risks to life and health, associated with a specific occupation, or the connection with death and decay. On the positive side are particular skills (in part a social construction) or other qualifications, the income generated by the occupation, and its connection with luxury production. The sixth question relates to who was allowed to do what work. What can we discover about divisions of labour relating to gender and age, to ethnic and religious affiliations, or to belonging to particular families, lineages, or voluntary associations, such as guilds? The seventh and final question concerns ideas about and approaches to realizing a “just” wage or other forms of remuneration.

Work ethics in the world, 1500–1650

In the history of norms and perceptions, 150 years may seem a short period, and we have often been asked why a period was chosen for our project's inception in which acute change and expansionist activity can be found in western Europe while other regions might appear to have been more static or passive. Different timeframes might be more meaningful for other world regions. Nevertheless, being based in western Europe, we consider it legitimate to start “digging where we stand”, fully aware that different cognitive maps are centred on other parts of the world and the periodicity of their rise to economic prosperity. A consideration of these differing timeframes must, indeed, form an integral part of this globally comparative exercise.

The first contribution to this volume, “Studying Attitudes to Work, Worldwide, 1500–1650: Concepts, Sources, and Problems of Interpretation” by Marcel van der Linden, sets the Global Collaboratory's approach in a broader methodological perspective that transcends the parts of the world and periods covered elsewhere by the other contributors to this volume. It deliberates on concepts of work, work incentives, and work attitudes, explores possible source types and their problems, and identifies problems of interpretation. These may include the researcher's projections of his or her expectations on to the available sources, or in false generalizations. The remedy for such problems is careful source criticism, critical self-reflection, and the contextualization of the observations made.

The subsequent contributions are geographically ordered. We set out from the Netherlands, turning south and east, before finally arriving in Portuguese and Spanish America.

The essay by Ariadne Schmidt, “Labour Ideologies and Women in the Northern Netherlands, c.1500–1800”, discusses the meanings of work in Protestant, humanist, mercantilist, and Enlightenment thought as reflected in books on conduct and household management. She concludes that in all of these philosophies, labour was held in high esteem. Paintings and conduct books of the period 1500–1650 present women working in the public sphere, as vendors and artisans for example, as unproblematic, though some of the conduct books emphasized that women should work at home.

Henk Looijesteijn's essay “Between Sin and Salvation: The Seventeenth-Century Dutch Artisan Pieter Plockhoy and his Ethics of Work” analyses the philosophy of one individual seventeenth-century thinker. Plockhoy (c.1620–1664) conceived of a work and life balance in which everybody should work. Idleness was a sin, but work should leave enough free time for spiritual obligations. His ideal was a community engaged in reciprocal labour, producing surplus for the market in the outside world. Wage labour for the market was to be avoided.

In “Attitudes to Work and Commerce in the Late Italian Renaissance” Luca Mocarelli compares two important late sixteenth-century writings that discuss the occupations in Italian cities. Garzoni, an Augustinian monk, presents a scholarly study of urban occupations, in a work presumably intended as a manual of instruction for a prince. Urban aristocrats at that time were contemptuous of merchants, and we find criticism of merchants in Garzoni's work. Fioravanti, the other author, was a gifted physician who led a restless life of travel and adventure and had probably seen with his own eyes much of what he described in his book. His intention, clearly, was to dignify all the various types of craft and trade he had observed, without ranking them as “noble” or “ignoble” as Garzoni does.

About fifty years later, by which time rural and urban proto-industry had spread, merchant-manufacturers emerged and wage labour in the manufacturing sector gained in importance. In “The Just Wage in Early Modern Italy” Andrea Caracausi shows that, at this point, a first systematic attempt was made by Lanfranco Zacchia, a Roman jurist, to establish legal norms on differentiated wage payment and other forms of remuneration. Caracausi then compares the norms with the labour disputes also recorded by Zacchia. The need for codification demonstrated the importance and the frequency of such disputes.

In an essay on Russia, “The Religious Aspect of Labour Ethics in Medieval and Early Modern Russia”, Arkadiy Tarasov discusses the impact of Orthodox Christianity on work ethics. As early as the second half of the fourteenth century, a process of monastic colonization commenced. The Russian Empire expanded far to the north and the east as the khanates of the Mongolian Golden Horde and their successors declined and disintegrated. The monasteries played a large role in the dissemination of Russian culture and the Orthodox religion. The author stresses that although the representatives of the Orthodox Church insisted on the importance of work, it was never considered an aim in itself, intended for economic success, as was the case in Catholic monasteries in western Europe. Instead, work was intended to advance spiritual development, and thus had a pedagogical rather than an economic function. This can also be seen in the Domostroi, a rule book which intended to set out the principles of household management for prosperous urban families. It was compiled in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and continued to enjoy a wide circulation well into the nineteenth century.

Karin Hofmeester's contribution, “Jewish Ethics and Women's Work in the Late Medieval and Early Modern Arab-Islamic World”, presents religious ideals as the basis of work norms, a gendered division of labour, and social ranking, with special reference to Cairo between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries. Paying special attention to the difference between text and social practice, she contrasts normative writings with legal documents for more immediate use, such as marriage contracts, court records on divorce, and wills. The picture that emerges is one in which all women were expected to work and have an income, also – at least in the ideal case – to allow their husbands some free time for contemplation and the study of religious texts. However, female activity had to be reconciled with the concept of zniut, or female modesty and restraint, which implied that women should have little contact with men and the outside world, and not leave their homes too often. Hofmeester argues that urbanization and the commercial revolution in the Arab-Islamic world led to the rise of waged work, and work opportunities at homes increased, especially as the textile sector flourished.

Shireen Moosvi's “The World of Labour in Mughal India (c.1500–1750)” first introduces the dominant types of labour relations, stating that commodified labour was fairly common in urban settings. Drawing on a variety of sources, this study stresses the importance of an official account of the Mughal Empire, the A'in-i Akbari by Abu'l-Fazl (c.1595). This record, while acknowledging the usefulness of manual workers and peasants, nonetheless transmitted a sense of superiority towards them. The Mughal emperor Akbar (reigned 1556–1605) was a famous exception to that rule, being purported not only to have valued manual labour highly but also to have personally undertaken several kinds of physical labour. In this contribution, we also find an approach to the actual voices of workers. The author presents them in the form of the religious songs composed by a group of manual workers (cloth-dyers, weavers, and peasants) referred to as monotheists. They rejected both Islam and Hinduism and in their lyrics insisted on the dignity of their professions.

Focusing on one occupational group within the Mughal Empire, in his article “Norms of Professional Excellence and Good Conduct in Accountancy Manuals of the Mughal Empire”, Najaf Haider analyses one specific type of source. Accountancy manuals were written by practitioners and conveyed a particular set of work ethics. Addressing the question of the division of labour and the entitlement to specific professions, the author explains that the change of language, calendar, and accounting system which the Mughal conquest engendered confronted Hindu clerks with competition from Muslim specialists. With the help of these handbooks, in the course of time Hindus too obtained the knowledge required to serve in the Mughal bureaucracy. This is reflected in the fact that the strict moral norms for this profession incorporated references to both Hindu and Muslim religious rituals and concepts.

Christine Moll-Murata's article, “Work Ethics and Work Valuations in a Period of Commercialization: Ming China, 1500–1644”, gives an overview of work ethics and how work was valued in another large centralized empire. The traditional classification of the ruler's subjects referred to scholar-officials, farmers, artisans, and merchants. The attitude of the official elite towards merchants was ambivalent, because merchants were establishing commercial networks that caused a mobility that seemed to threaten the existing social order.

The voices of the great majority who worked in reciprocal and subsistence rural labour relations are heard much more rarely, though, and need to be detected using indirect evidence. Lyrics and songs that can be confidently dated to the period under observation are descriptive rather than self-expression. They concern mainly the urban trades and show great diversification.

In her essay “Prostitutes and Courtesans in the Confucian Moral Universe of Late Ming China (1550–1644)”, Harriet Zurndorfer demonstrates a shift in the value attached to the work of prostitutes and courtesans during the last 100 years of the Ming dynasty and the transition to the Manchu Qing. This shift affected the high-class courtesans rather than the lower-class prostitutes who worked in cheap brothels and remained in socially and legally more marginal circumstances. The courtesans were more highly esteemed during the late Ming period. As the philosophical ideas of the Confucian philosopher Wang Yangming took root, the idea of individual self-cultivation and free expression of one's emotions spread among the urban literati. The courtesans and their clients could regard themselves as enacting freedom, independence, and bravely overcoming the conventional boundaries between the private and the public. This so-called “cult of the qing” (true feeling) gained popularity also among gentry women, who lived a secluded existence in their homes.

Turning to Japan, Regine Mathias portrays a rural society that experienced a change from predominantly reciprocal and tributary labour relations to the beginnings of commodified labour. In “Japan in the Seventeenth Century: Labour Relations and Work Ethics”, the author discusses the largely unsuccessful attempts of the new political system to curb mobility and flexibility. Confucian scholars of the “School of the Heart” propagated ideas of the worthiness and equal value of all occupational “callings”, even of the merchants. The concept of the “four occupational groups” had been adopted from China, but it was less firmly rooted in Japan. Therefore, and because of the different relationships between the commercial sector and the bureaucracy, the enhancement of the merchants’ role was less problematic. Mathias also evaluates the contribution of women to rural proto-industrial activity. These were most considerable in textile production. Women were not expected to remain at home; they worked in the fields alongside the male members of their families.

The last group of articles in this volume treats labour relations and work ethics in colonial settings in South America and the imposition of unfree labour on Amerindian and Afro-American people. The essay by Tarcisio Botelho, “Labour Ideologies and Labour Relations in Colonial Portuguese America, 1500–1700”, discusses the justification for the dominant labour relation in the Brazilian sugar mills, the unfree commodified labour forced upon the Afro-American slaves. The author sets the ranking of occupations into the context of the medieval three estates that applied in Portugal in the fifteenth century. The notions of the tripartite European system of “those who pray”, “those who fight”, and “those who labour” were at the root of Brazilian slavery, since the masters of the sugar mills conceived of themselves as belonging to the nobler classes, who were not expected to do manual work. In their sermons to the African slaves in Brazil, the Jesuit missionaries argued that the slaves were being held in captivity in order to save their souls, and their suffering was likened to the passion of Christ and defined as a punishment for the original sin of mankind.

The second essay on South America, “Free and Unfree Labour in the Colonial Andes in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries” by Raquel Gil Montero, enquires into the nature of a particular kind of tributary labour relation inflicted upon the native population living in the vicinity of Potosí, in present-day Bolivia, where large silver mines were being operated. It has been argued by historians of Latin America that the forced-labour obligations, the so-called mita, were a kind of voluntary unfree labour. Closer analysis of colonial statistics and contemporary reports reveals that some of the labourers were in fact going to the mines voluntarily, in spite of the harsh working conditions there. While some of the natives were obliged to render service, others could pay monetary tribute. The wages for free labour were higher, and hence the tributes could be paid off sooner by working in the mines voluntarily. The Potosí mita thus created a kind of dual system, where tributary and commodified labour relations existed side by side.

Global conjunctions and differences

Between 1500 and 1650 most of the world's population were unaware of the existence of other countries, let alone continents; nor could they comprehend whether, or how, events abroad influenced their own life and work. For some, however, being linked to a commercial circuit became an experience that profoundly affected their existence.

In the period 1500–1650, European naval powers expanded eastward and westward. Dutch and British ships arrived on North American shores and those lands were settled, while the Portuguese and Spanish monarchies declared parts of South and Central America their colonies. The relationship of those colonies to Europe, from where powerful groups tried to transpose their values and work ethics on to the South American territories, becomes clear not only in the essays on Brazil and Potosí but also in that on Plockhoy, the Dutch practical visionary whose North American settlement formed a testing ground for ideas on work developed earlier in the Netherlands, England, and Ireland.

Early modern Europe was bound in a multitude of ways to the Mediterranean. Important for our context are the connections between the Spanish Reconquista, the Inquisition, and the exodus of Jews from Spain to other parts of Europe and the southern Mediterranean, including Cairo.

Further east, the conjunctions are also evident. By the thirteenth century, the Mongols had conquered and were ruling an enormous empire. As Mongol rule disintegrated, the Russian Tsars extended their territory in the second half of the sixteenth century to include Siberia. One descendant of the Timurid Mongolians struck out southward and conquered India. Still further east, the Ming dynasty had forced the last emperor of the Mongol Yuan dynasty to flee north, but the Mongol threat persisted throughout the Ming. Japan remained unaffected by direct Mongolian influence, but the circle closes when we consider the eastern expansion of the Portuguese and Dutch East India companies, which reached India, China, and Japan in the sixteenth century. Some of the articles in this volume show how labour systems and work ethics were affected as ideas and commodities travelled along those routes. It is in this global and spatial setting that the articles investigate the layers and perspectives of work ethics and valuation of work.

The sources for our historical enquiries are texts, and to a certain extent images too. The most desirable and straightforward type of text for analysing the voices of those who actually worked, their self-valuations, and their attitude towards their work, would seem to be autobiographical ego documents. However, such documents are completely lacking in our samples. In fact, even for European regions where they do exist, they often do not express attitudes towards work. By way of explanation, James S. Amelang argues that “self-writing was a practice different from, and even alien to work”, a contention that accords with James Farr's observation that “early modern artisans were indifferent or even hostile to work”.Footnote 17 In the samples of workers’ voices we have in this volume, the Indian weaver's song and the Indian handbook written by clerks for clerks, the former stands in close relation to the religious elevation of work, and thus “lifts the curse” by likening craftwork with divine creation. The other tells professionals the secrets of the trade, and advises them on how to behave in private life. It is thus normative rather than descriptive.

In sum, for several reasons the voice of workers is difficult to discern for periods when work was not yet an isolated feature for all or most people. The case of the utopian thinker, Plockhoy, is special since he, as an artisan, still tried to set norms rather than describe actual conditions. Yet, implicitly, his work contrasts the situation in his utopian society with actual labour relations, showing how Plockhoy despised the position of wage workers outside his society. The other articles also give us hints. Even though work songs from China and Japan are difficult to date, they still tell us something about the valuation of physical labour. The Jewish women in late medieval Cairo who went to the Islamic court to fight for the right to keep their own earnings demonstrate that many Jewish women worked for an income, that they valued this, and regarded it as their property.

This meant that, if possible, people made deliberate choices, and these reflect their valuation of work. The article by Raquel Gil Montero suggests that people sometimes opted for harsh working conditions in the mines, performing free, monetized labour in order to pay off tributes, rather than rendering labour service. The Chinese upper-class ladies who copied the lifestyle of courtesans show how the ladies of high society valued a position of freedom and independence. The Italian men, women, and children who went to court to sue for “just wages” not only prove that wage labour had become a widespread, institutionalized, and accepted form of labour in Renaissance Italy, their litigation also demonstrates that workers regarded their labour as subject to an inviolable contract between worker and employer.

Texts created by secular or clerical authorities are obvious sources of information on work ethics and on how work was valued; thus legal or religious norms and regulations can be found for most of the regions studied. Apart from canonical texts, we find in all societies conduct books for cloisters, households, ideal societies such as Plockhoy's, real societies such as Italian cities, and greater regions and spheres of power, such as empires.

Rather than describing the actual situation, they represent model situations. These texts were often written in periods of change and dictated rules of work that were not, or no longer, in accordance with social practice. Examples include the development of market economies and the role of the merchant class, so detested by Plockhoy, Zacchia, and others, and suspected by Chinese officials such as Zhang Han; the proliferation of free wage labour, which Garzoni would have preferred to ban; and the increase in women's work outside the home, of which different types of Dutch conduct books as well as rabbinical writings did not approve. Sometimes, those texts were intended to provide proper guidelines for the new situation, such as Fioravanti's rules on proper wages, or to inform the public or administrators of new work specializations, such as the Chinese and Japanese agricultural handbooks which also commented on the gendered division of labour. Directly or indirectly, they reflected the actual situation and tried to set norms for achieving an ideal situation.

Since Le Goff, historians of work have paid particular attention to the time factor in changes of work organization. In many of the societies described here, wage labour increased, and it was formalized in contracts, in which time played an important role. However, in the cases presented here, time is not always mentioned in relation to work contracts. Also, Dutch household management books show that reciprocal work and unfree labour within the household continued. The standard contract for the sale of daughters in the Chinese household encyclopaedia does not mention a period of commitment, and the rules in the Russian Domostroi suggest that the lady of the house should always be ready to give orders to her servants and be prepared to work herself. Apparently, texts not only described ideal situations in response to changing labour relations, they also signalled continuities, such as the never-ending phenomenon of non-wage labour, which was often performed by women.

Concerning the expression of work and the value attributed to it, in almost all the societies treated in this volume we found texts that valorized “work”. Often “work” was esteemed as an abstract concept, as opposed to idleness. Female idleness seemed particularly harmful. The terms labor/labour/lavoro, Arbeit, travail/trabalho in the European context, but also lao/rō in China and Japan, were associated with “pain” until the early modern period. In Indo-Persian, this conjunction can also be found in the common designation for labour, the Persian words mahnat (literally “pain”) and ranj (literally “grief, pain, toil”).Footnote 18 Since Max Weber, the idea that in the sixteenth century work was not only divine retribution for the original sin of mankind, but also a divine “calling”, has often been pointed out. Likewise, in Japanese, a seventeenth-century term for work also implies “heavenly calling” (tenshoku). However, if work was held in higher esteem from 1500 onward – some scholars stress a continuity that included the period prior to 1500 – did this also imply that it was a “joy”, and that the accumulation of recompense for work, which Max Weber ascribed to the “Protestant ethic”, was an ultimate goal?Footnote 19

The articles in this volume do not give a consonant answer to this question. Work in the Brazilian sugar mills needed to be justified by reference to the original sin of mankind, and other oppressive work conditions – that stressed the pain rather than the joy of work – are discussed in this volume. The occupational specializations analysed in works such as those by Garzoni and Fioravanti, or in Chen Duo's songs on urban occupations, which might potentially express the joy of work, could have been due to the interest and pride of the elites or middling classes in an affluent and sophisticated environment. The attractive features of the rice-planting women in Japanese fields were praised in an agricultural treatise. This is the onlookers’ perspective, which may have been joyful and entertaining. Some of the images of people at work in this volume were designed to satisfy this interest or to suggest joy in the work of others and to convey the message of harmonious labour relations.

Many religions promise metaphysical rewards for a life of hard work and punishment for a life spent in idleness, or, as in the Christian case, claim that the strain of work was the redemption for man's original sin. However, all religious ethical systems also insist on the importance of spiritual engagement, and demand that sufficient time be reserved for contemplation in everyday life. Between 1500 and 1650, activity and contemplation formed an indissoluble bond, as far as the religious authorities studied in this volume – Christian (Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox), Jewish, Muslim, Indian monotheist, Confucian, and Buddhist – are concerned. The time spent on non-working activities (i.e. on not adding use value to goods and services) was, from these religious perspectives, at least as joyful as the time spent on work, though often this was not made explicit.

In many of the regions discussed in this Special Issue, we see the consequences of rapidly developing transcontinental markets, including urbanization and the development of free wage labour. In the Dutch Republic and the cities of Italy and China we see a shift from combined reciprocal and self-employed artisan labour to more commodified labour. The contributions also demonstrate shifts from slave labour (Arab-Islamic north Africa), serfdom, and indentured labour (Japan) to free wage labour. In India commodified labour seems to have already been widespread by the end of the sixteenth century, so here the major shift might have taken place before 1500.

The growing extent of free wage labour in western Europe and Asia coincided with a shift from reciprocal labour to slavery in the Spanish and Portuguese colonial empires. This leads to one of the core questions addressed by this Special Issue. Was commodified labour valued differently from other forms of labour relations, and did the increase in wage labour prompt an increase in the discourse on labour?

The answer is ambiguous. We see in the work of Garzoni and Plockhoy a true distaste for wage labour. Garzoni, writing for aristocrats keen to preserve the social hierarchy, had a special reason for that. Plockhoy despised the position of wage workers as they had to sell their labour to the abject class of merchants. Reciprocal labour was his ideal. In Chinese cities, the freedom and independence of wage labour (as compared with indentured labour) was clearly valued, since we see people moving voluntarily in that direction, just like workers in Japan, where rulers first tried to prevent geographical and occupational mobility.

Once commodified wage labour led to new thinking and conflicts regarding contracts, hours of work, and other aspects of labour relations, it automatically triggered greater discourse on labour. Also, the growing number of women working for wages (sometimes outside the home, and sometimes wanting to keep their own income) led to debates concerning the nature of work. At the same time, we must remember that both in rural areas and within cities reciprocal labour was still very much the norm. In Brazil, the shift from reciprocal or tributary labour to slavery also led to a “labour discourse”, if we can term as discourse the justifications adduced by Jesuit missionaries in their sermons.

Many of the studies in this volume show the fluidity of the categories “free” and “unfree” labour. This is clearest in the article on forced labour in Potosí, where free and the unfree workers all ended up working in the same mine. Yet the ability to meet one's labour obligations by payment of a monetary tribute could mean the difference between life and death, which is why local people insisted on the option of paying tribute rather than rendering labour service.

The article on Brazil discusses the shift from first enslaving part of the Indian population, to resorting to Afro-American enslavement for securing a supply of labour in the sugar mills after the demographic decline in the 1560s. The Portuguese also established a different kind of less unfree work organization, which involved organizing those Indians who worked for the Portuguese and were subject to reciprocal labour, into hamlets controlled by religious orders, mainly Jesuits. The shift here occurred from one ethnic group to the other, and saw labour relations among the Indians being transformed from outright slavery to life and work under Portuguese control.

In some cases in China voluntary bonded labour arrangements could be entered into on a temporary basis. In China, as in Japan, the boundary between unfree service to an upper-class landowner or feudal lord and free labour arrangements could be transgressed if a serf proved able to buy his own land and freedom. A less costly status which also involved less freedom for the former serf or bondservant was tenancy, with the tenant leasing from his former master. Finally, the unfree labour undertaken by prostitutes could be transformed into concubinage, thus changing the type of labour relation into that of reciprocal household work.

In all the societies discussed here, whether Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox Christian, Perso-Islamic, Jewish, or Confucian, occupations were ranked according to specific criteria. These were hierarchical systems of orders, estates, or castes in which manual labour was found mostly at the bottom, the exception being the “four occupational groups” of China and Japan, where farmers were allocated to the two upper classes. Intellectuals and clergy were generally found at the top, unless they belonged to orders that were – in theory – viewed with suspicion by the state, such as Daoists and Buddhists in China.

As the articles show, in practice those rankings were not fixed and rigid; they were sometimes reconsidered, and could be revised over time, especially when people, commodities, and ideas began to circulate. The Persian ranking found in Mughal India gave precedence to warriors, followed by artisans and merchants, while men of letters occupied a third category and clerics were not included at all. This contrasted with the previous Hindu orders, which categorized people as priests, rulers and warriors, traders, or manual workers, with a residual category of menial workers and outcastes.

In China, change also occurred within the group of menial labourers. For almost a century the better-off prostitutes achieved a kind of glamorous and heroic image, as external trade expanded, cities flourished, and a cosmopolitan lifestyle formed a fertile breeding ground for the development of theories of individual morals. Another example is the notion of the medieval European three estates exported from Portugal to Brazil: in the colony, merchants became nobles, moving from the third to the second estate. As flexible as these taxonomies might have been, people still defined themselves and were defined by others in terms of their work, as Tarcisio Botelho has shown.

In the period between 1500 and 1650, access to work was not free to everybody. Various criteria for inclusion in or exclusion from particular sectors of production and services applied. The most important were gender, ethnicity, hereditary occupation, as with the castes, and region of origin.

Almost all the essays in this volume show gender to have been important. In many contexts the main argument was that women should work in the home, and in emerging proto-industrial or commercializing settings that they should also work in their homes for the market. Domesticity was an ideal in normative texts in the Netherlands, Cairo, and China. For the Dutch Republic, it has already been argued that the affluence gained through overseas trade enabled Dutch men to work as the family's sole breadwinner and women to confine themselves to household work. However, as Ariadne Schmidt shows, this change did not take root until the eighteenth century. Evidence more empirically valid than conduct books and philosophical reasoning suggests that, in reality, women did work outside the home, though to a variable extent. It is interesting to note that Japanese female farmers were expected to transplant rice seedlings, while this was not always the case in China; and that Jewish women in Cairo who originated from the Iberian peninsula had more chances to engage in income-generating domestic production, and more possibilities to make decisions concerning their own property, but less opportunity to go out in public.

Indian women worked both in their own homes and outside. Shireen Moosvi reminds us that even in market economies most women's labour was reciprocal, and women would assist their male family members if they worked at home. Women went outside the home, and even to construction sites, to work as porters. There was little competition between women and men for most occupations, which again shows that gender was an important criterion for inclusion in or exclusion from particular occupations. For India, occupational restrictions largely affected the castes of Hindu communities, which were endogamous and had particular occupations allocated to them. Although the caste system changed over time, the scope it allowed for horizontal or vertical mobility remained limited. Hereditary occupations were also a feature of the Chinese system of labour obligations. Military, artisan, and salt-producing households in particular were obliged to serve the state in particular roles. However, after 1500 this system was replaced largely by monetary tax payments, a tendency which led to greater flexibility on the labour market.

Ethnicity was another important criterion determining who could do what work. This is explained for the unfree labour conditions of Afro-Americans and Indians in Brazil, and the Indian native population of Potosí, the most striking samples in this volume. Yet cases of a more limited range in which people of a particular descent were forced or entitled to work in specific occupations can be found all over the globe. At one end, for instance, we find among China's “official prostitutes” the descendants of Mongols who had remained in China after the defeat of the Mongol Yuan dynasty. At the other, after 1644, Manchus, Mongols, and their bondservants, the so-called “banner people”, occupied all the top-level military and administrative offices in the Qing empire following the demise of the Ming dynasty. Within those extremes, descent and networks played key roles in the commercializing and mobile early modern world. From Europe there are examples of porters working in Milan, most of whom were of Swiss origin,Footnote 20 and of Scottish mercenaries in the armies of the Netherlands during the Dutch Revolt and in Danish and Swedish armies during the Thirty Years War.Footnote 21

Although some of the source types presented in this volume, such as books of household management, can be found almost everywhere, others were particular to specific regions. Those include Zacchia's codification of wage-related law, and the collection of guild adjudications in labour conflicts. The Italian wage codifications and the role of corporations in labour-related adjudication are paralleled by the guild institutions of the Arab and Ottoman world.Footnote 22 Yet the systematic focus on wage jurisdiction is extraordinary and must be attributed both to a specific legal tradition as well as to the importance of wage labour and wage disputes in Renaissance Italy.

To conclude

In many countries, the study of early modern labour relations is still in its infancy. For a number of countries then this Special Issue provides a much-needed overview of developments in labour relations, one which also discusses what we know at this point about how labour and labour relations were perceived.

Work ethics and the valuation of work in what for some regions is regarded as the “early modern” period, in others, such as Mughal India and the Arab-Islamic world, as “late medieval”, do not converge into a single trend. On the basis of this inventory, we can conclude that while peasant self-subsistence was still the rule in most regions, commodified labour increased in the cities of Europe and South and East Asia, and also in the colonial empires of South America, varying from free wage labour to chattel slavery. This was the result of what today is perceived of as the beginning of globalization, which linked previously unrelated world regions through relationships of trade and often also exploitation.

The voice of the elite concerning the change in the lives of those who worked is anxious in some cases, but full of marvel at the diversity of occupations in others. The traces of the opinions of the working non-elites about their lot are faint, but we find self-assertion in some cases, and a struggle (or the conviction that one should struggle) for more control over the labour process and its remuneration in others.

The period 1500–1650 was one where the dichotomy of activity and contemplation, or self-fulfilment, and in some cases redemption through work, played a central role in work ethics. Labour relations and occupations determined social stratification and vice versa. Kings hardly ever engaged in physical work, while housewives always did. Those in between, if their voices can be made audible, would object to the hardships of work, but occasionally find ways to enjoy it. Changes in work and labour relations could imply greater freedom and bargaining options, but at the same time an infringement on personal choices and preferences, engendering joy for some and pain for others in all the world regions represented in this volume.

Appendix

DEFINITIONS OF LABOUR RELATIONS

Non-working

1. Cannot work or cannot be expected to work: Those who cannot work, because they are too young (≤6 years), too old (≥75 years),Footnote 1 disabled, or are studying.

2. Affluent: Those who are so prosperous that they do not need to work for a living (rentiers, etc.).

3. Unemployed: Though unemployment is very much a nineteenth- and, especially, twentieth-century concept, we distinguish between those in employment and those wishing to work but who cannot find employment.

Working

reciprocal labour

Within the household:

4. Leading household producers: Heads of self-sufficient households (these include family-based and non-kin-based forms, such as monasteries and palaces). In many households after 1500, “self-sufficiency” can no longer have been complete. Basic foodstuffs, such as salt, and materials for tools and weapons, such as iron, were acquired through barter or monetary transactions even in tribal societies that were only marginally exposed to market production.Footnote 2 ”Self-sufficiency” in our sense, which occurs in labour relations 4, 5, and 6, can include small-scale market transactions that aim at sustaining households rather than accumulating capital by way of profiting from exchange value.Footnote 3

5. Household kin producers: Subordinate kin (men, women, and children) contributing to the maintenance of households.

6. Household servants: Subordinate kin and non-kin (men, women, and children) contributing to the maintenance of households. This category does not refer to household servants who earn a salary and are free to leave their employer of their own volition, but rather to servants in feudal autarchic households.

Within the community:

7. Community-based redistribution agents: Persons who perform tasks for the local community in exchange for communally provided remuneration in kind, such as food, accommodation, and services, or a plot of land and seed to grow food on their own. Examples of this type of labour include working under the Indian jajmani system, hunting and defence by Taiwanese aborigines, or communal work in nomadic and sedentary tribes in the Middle East and North Africa.

tributary labour

8. Forced labourers: Those who have to work for the polity, and are remunerated mainly in kind. They include corvée labourers, conscripted soldiers and sailors, and convicts.

9. Indentured tributary labourers: Those contracted to work as unfree labourers for the polity for a specific period of time to pay off a debt. For example, German regiments (the “Hessians”) in service with the British Empire which fought against the American colonists during the American Revolutionary War.

10. Tributary serfs: Those working for the polity because they are bound to its soil and obliged to provide specified tasks for a specified maximum number of days, for example, state serfs in Russia.

11. Tributary slaves: Those who are owned by and work for the polity indefinitely (deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to receive compensation for their labour). One example is forced labourers in concentration camps.

commodified labour

For the market, private employment:

12. Self-employed: Those who produce goods or services for market institutions, possibly in cooperation with other household members or no more than three wage labourers, apprentices, serfs, or slaves (for example, peasants, craftsmen, petty traders, transporters, as well as those in a profession).

13. Employers: Those who produce goods or services for market institutions by employing more than three wage labourers, indentured labourers, serfs, or slaves.

14. Market wage earners: Wage earners who produce commodities or services for the market in exchange mainly for monetary remuneration.

14.1. Sharecropping wage earners: Remuneration is a fixed share of total output (including the temporarily unemployed).

14.2. Piece-rate wage earners: Remuneration at piece rates (including the temporarily unemployed).

14.3. Time-rate wage earners: Remuneration at time rates (including the temporarily unemployed).

15. Indentured labourers for the market: Those contracted to work as unfree labourers for an employer for a specific period of time to pay off a debt. They include indentured labourers in the British Empire after the abolition of slavery.

16. Serfs working for the market: Those bound to the soil and obliged to provide specified tasks for a specified maximum number of days, for example, serfs working on the estates of the nobility.

17. Chattel slaves who produce for the market: Those owned by their employers (masters). They are deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to receive compensation for their labour.

17.1. Sharecropping chattel slaves working for their proprietor, for example, plantation slaves working in the Caribbean.

17.2. Slaves for hire, for example, for agricultural or domestic labour in eighteenth-century Virginia.

For non-market institutions that may produce for the market:

18. Wage earners employed by non-market institutions: Such as the state, state-owned companies, the Church, or production cooperatives, who produce or render services for a free or a regulated market.

18.1. Sharecropping wage earners: Remuneration is a fixed share of total output (including the temporarily unemployed).

18.2. Piece-rate wage earners: Remuneration at piece rates (including the temporarily unemployed), e.g. hired artisans in Chinese imperial silk weaveries during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

18.3. Time-rate wage earners: Remuneration at time rates (including the temporarily unemployed), e.g. hired artisans on Chinese imperial construction projects during the Ming and Qing dynasties, but also workers and employees in twentieth-century state enterprises.