At 11.59 pm on 14 September 1970, over 400,000 workers struck General Motors (GM), the biggest corporation in the world.Footnote 1 It was a massive walkout, lasting sixty-seven days and affecting 145 GM plants in the US and Canada. In the US alone, the strike affected sixty-nine cities in eighteen states.Footnote 2 As a result of the dispute, GM lost over $1 billion in profits, recording the biggest quarterly loss in its sixty-two-year history. Due to the industry's size – at the time, one in six American jobs were reportedly linked to automaking – the US economy lost over $1 billion in tax revenue and hundreds of millions of dollars in retail sales. The walkout also had a huge impact on the United Automobile Workers (UAW), which disbursed over $160 million in strike benefits. As reporter William Serrin has noted, the General Motors strike of 1970 was one of the “largest and most expensive strikes in American history”.Footnote 3

Little is known, however, about this landmark strike. Fifty years later, the only detailed account remains Serrin's The Company and the Union (1973). Written shortly after the strike, Serrin controversially dismissed the dispute as a “political strike”, designed to shore up the position of new UAW president Leonard Woodcock and win ratification of a new national contract. The strike, Serrin asserted, reflected a “civilized relationship” between GM and the UAW and lacked drama.Footnote 4 In Stayin’ Alive (2010), an influential history of workers in the 1970s, Jefferson Cowie struck a similar tone. The GM walkout was a “titanic undertaking”, Cowie admitted in brief coverage, yet it “hardly rattled the golden cage of postwar industrial relations”.Footnote 5

For Cowie and others, the “real drama” occurred elsewhere, especially during the 1972 strike at General Motor's plant in Lordstown, Ohio. Here, young, rebellious workers fought against the humiliating speed-up, attracting widespread media attention. In contrast, the GM strike “lacked the proletarian drama that fired journalists’ hearts”.Footnote 6 Although it was much smaller, the “notorious” Lordstown strike has received more scholarly attention.Footnote 7 As the focus on Lordstown illustrates, rank-and-file discontent has been well-documented, infusing scholarship on the 1970s.Footnote 8 Unlike Lordstown – and many other strikes of the time – the 1970 GM dispute was not a wildcat. In general works on American labour, the strike continues to be largely ignored.Footnote 9

Reclaiming the 1970 GM Strike: The Approach

This article contends that the GM strike deserves a fuller treatment. The first to use detailed archival records of the strike, including transcripts of the negotiations, UAW executive board minutes, and grassroots union files, it uncovers a multifaceted – and compelling – story. It is a story with wide-ranging local, national, and international implications.Footnote 10

I argue that the strike mattered, for several reasons. It was a huge undertaking, especially given GM's size. Despite this, the UAW achieved a lot, winning significant wage increases, better healthcare, retirement after thirty years, an end to cost-of-living allowance caps, and no restrictions on the number of grievances that could be filed. Crucially, they also addressed many grassroots concerns, especially about safety within the plants. The strike was also part of an international upsurge of labour activism, and the UAW secured considerable public support, both domestically and globally. Primary sources show that workers and union leaders were heavily invested in the battle, which reflected deep-seated local, national, and global issues (including concern about line speeds). Participants fought hard to secure redress of local issues, which were at the heart of the strike. Overall, this was a struggle worthy of more serious consideration, especially as it was a signal to the labour movement – and nation – that GM was not too big to strike. Prior to 1970, the UAW had made Ford or Chrysler, who were smaller, its strike target during Big Three negotiations, so what happened that year was significant. According to Dennis McDermott, the UAW's Canadian director, the union had “put to rest the rumor that GM is too big for us and that we always picked Ford and Chrysler because they were the weak sisters”.Footnote 11

What, though, does this story contribute to the literature? The few existing accounts have focused on the strike's national impact, viewing it – rather narrowly – through the lens of the UAW–GM bargaining relationship. Concentrating on the union's national demands, which were heavily economic, Serrin dismissed the UAW as a “dollars and cents” operation, only concerned with paychecks and economic gains. Others drew similar conclusions. This, however, is only part of the story.Footnote 12

The strike needs to be viewed with a wider lens, one that captures its drama and full impact. In the account that follows, the story of the strike is reclaimed and re-interpreted, with a consistent emphasis on its neglected social dimensions. This was a national strike, but it was also much more. The story is built through a chronological approach, outlined in sub-sections that explore the strike's course, settlement, and impact. The focus moves beyond the national, with little-known local dimensions driving the story. Many workers, for example, went on strike before the national authorization and stayed out after the top-level settlement was made. Little-known global dimensions are also uncovered.Footnote 13

Reflecting this, strikers received support and encouragement from workers around the world, from places as diverse as Israel, Japan, the USSR, Venezuela, and West Germany. Even workers in secretive North Korea wrote in support.Footnote 14 The UAW sold these international dimensions well. “I have carried the case of UAW–GM strikers to the leaders of auto and metal workers of other lands to ask for their solidarity support of our strike efforts against the GM Corporation”, summarized Victor Reuther, the union's International Affairs Director. “Hundreds of messages of such support are pouring into Solidarity House and to the UAW's International Affairs Department.”Footnote 15 For workers across the globe, the UAW was inspiring partly because of its bargaining achievements. In the battle with GM, a giant with many overseas plants, they also saw it as fighting for workers everywhere. As Belgium's Metalworkers’ Federation summarized, the GM strikers were a “counter-power to the big corporations”.Footnote 16

The strike also involved scores of local stories. These are particularly important in understanding its full history, especially from a social basis, an approach that has been overlooked. As archival records demonstrate, for many workers, shopfloor issues – most of them non-economic – were paramount in triggering the dispute. During the strike, Reuther related, the UAW faced an “enormous backlog of grievances over local issues”. Key strike issues for workers included “the speed of the line, health and safety conditions and a host of other factors”. Taken together, these questions were “more important in the minds of the workers than more cash in their pay envelope”.Footnote 17 According to UAW regional director George Merrelli, rank-and-file restlessness was at the heart of the strike – as it was in many other struggles in the 1970s. “Key to the solution is to get the Local issues solved”, he told the executive board on 22 October. Highlighting this, some local strikes lasted for six weeks after the national settlement was agreed. Like the better-known Lordstown strike, the GM walkout had plenty of local drama, and reflected the same frustrations, especially younger workers’ unwillingness to tolerate arduous and unsafe working conditions.Footnote 18

A lot was at stake. Striking GM was a huge task, taking planning and commitment. The 1970 strike, summarized the UAW's Irving Bluestone, was a “gallant fight”, a seismic battle between America's largest employer and its biggest industrial union. It also occurred in a high-profile – and talismanic – industry. At the time, automaking dominated the US economy, and GM was the biggest force in the industry, controlling half the domestic market.Footnote 19 As secretary-treasurer Emil Mazey told his colleagues during the strike, the “whole union” was “on test” in the struggle. “We have never gambled with the future of the International Union as we are now”, he admitted.Footnote 20 “There were many inside and outside the Union who expressed grave fears that General Motors was too powerful, too big and too wealthy to take on”, added Bluestone, the UAW's lead negotiator in the strike. “But we did take on General Motors and we won.”Footnote 21

The 1970 Strike: Wider Significance and Context

The strike's success reinforces its wider significance. Scholars who have looked at contemporary labour history have been heavily focused on defeat and decline, with works on falling union density being especially prolific.Footnote 22 A successful struggle, the GM strike challenges this narrative. As a result of the walkout – which was solidly supported from coast to coast – the UAW won many concessions.Footnote 23 As Mazey put it, the agreement contained “the biggest wage settlements (and) the biggest economic package that we have ever obtained in the history of our bargaining”. According to a union analysis, these were “historic” gains. There were further advances in scores of local contracts, which were ratified separately.Footnote 24

In a broader context, the strike is important as part of an emerging body of scholarship on the 1970s that has questioned notions of labour's decline. As historian Philip F. Rubio has argued recently, the 1970s was a “decade of strikes”, starting with the “transformational” national postal strike of March 1970, which also resulted in major gains for workers. In many areas, union membership surged in the 1970s, especially in the public and service sectors. The 1970s, explains Lane Windham in Knocking on Labor's Door (2017), offered “fresh promise for America's working class” and featured “tremendous organizing efforts”. Workers did not “give up” – something that the 1970 GM strike ably demonstrates. Their story is integral to this wider history.Footnote 25

As Windham demonstrates, we need to challenge the narrative of decline in the 1970s, especially as much of what we consider to be decline did not happen until the 1980s. It was in the 1980s, with the election of Ronald Reagan and Republican control of the Senate (which the GOP secured in 1980, for the first time since 1954), that union density plunged precipitously. Between 1955 and 1980, union density fell slowly, from thirty-two to twenty-four per cent, often because of the rapid growth of the service sector, which unions struggled to keep up with. In the 1980s, however, the pace was much more rapid; by 1989 density stood at just 16.8 per cent. In less than a decade, therefore, union density had fallen by almost as many percentage points as in the previous twenty-five years.Footnote 26

Workers in the 1970s, moreover, did not know what future decades would bring for themselves or their industry. Many defining labour battles occurred in what Judith Stein has termed a “pivotal decade”, or what several other scholars have termed a “hot” decade, worthy of closer consideration as a transformational time. In 1970 alone, one in six of all union members in the US went on strike.Footnote 27 It is important to explore workers’ history as it occurred, and not to view it through the lens of subsequent industry or union decline. A successful battle against the biggest corporation of all, the 1970 GM strike should be at the heart of this reassessment. As AFL–CIO President George Meany put it, GM workers won a “splendid victory” in a strike that was “vital to all American workers”.Footnote 28

The timing of the strike was also important. The GM dispute was at the heart of the 1968–1974 “upsurge” in labour militancy, an international movement that Sheila Cohen has termed an “explosion of potentially subversive working-class activity”. In Britain, the number of strike days rose from less than five million in 1968 to 13.5 million in 1971 and 23.9 million in 1972. In the US, strike activity exceeded that of the 1930s, an heroic era that has received much more scholarly attention.Footnote 29 Between 1967 and 1971, as US labour historians have shown, every measure of militancy, including the number of strikes, the percentage of time lost, and the number of workers on strike, rose sharply over figures for the early 1960s.Footnote 30

The decade's opening year was particularly important. In March, more than 200,000 US postal workers struck, winning a pay increase and collective bargaining rights. This breakthrough helped other public sectors workers make decisive gains.Footnote 31 It is important that the GM strike – a bigger dispute than the postal walkout – also be recognized as a key part of the labour militancy of the 1970s.Footnote 32 In the last two decades, moreover, scholars have re-visited the 1970s, overthrowing early views of it as a time when “nothing happened”. Rather, the 1970s has increasingly been viewed as an important decade that witnessed important activism, with civil rights, labour, and human rights struggles all advancing. The decade also witnessed increasing internationalism, a development that this story illustrates surprisingly well.Footnote 33

The Strike: Buildup

Strikes forged the UAW's character, a point worth remembering as we re-claim the history of the 1970 dispute. In 1936–1937, it was the sit-down strike in Flint, Michigan, a legendary forty-four-day confrontation, which forced GM to bargain with the union after years of resistance.Footnote 34 The UAW was born, and its relationship with GM, the biggest automaker, was key from the start. Following the Flint strike, the union pressured GM to share more of its profits with its workers. During World War II, these demands were put on hold, but straight after the war the UAW struck GM for 116 days, another defining dispute. In the settlement, the union won a significant wage increase and other advances. Although GM resisted president Walter Reuther's calls to “open the books,” the 1945–1946 strike cemented Reuther's place as a powerful labour leader. The strike instituted a relatively stable bargaining relationship, one that was widely admired for the gains it produced, partly because GM was so dominant that it could pass on increased costs to the consumer. The 1970 strike was significant partly because it ended this long period of labour peace, which had helped define the postwar period and its image of economic security.Footnote 35

After the 1945–1946 strike, the relationship between the UAW and GM became pattern-setting. The 1948 contract, noted company vice president Harry Anderson, was particularly important, for all American workers. “In the spring of 1948 General Motors and the UAW–CIO pioneered in establishing important principles for collective bargaining”, he explained. These principles set the basis for subsequent contracts, which were designed to “protect the purchasing power of employes’ wages, improve their standard of living, promote efficient production and establish a basis for harmonious relations”. As a result, for the “first time in labor-management history”, the two sides agreed to long-term contracts. Initially, contracts were for two years – rather than annual – but this evolved into three or five years.Footnote 36 The 1948 contract also pioneered cost-of-living allowances and annual improvement factor increases, state-of-the-art improvements. In the 1940s, the UAW and GM also instituted the impartial umpire system, a jointly appointed – and renumerated – official who ruled on disputes that the parties could not resolve. The company was proud of what Anderson called “good old collective bargaining”, especially in the 1950s and early 1960s, when its prosperity and size facilitated generous wage and benefit increases.Footnote 37 Beginning in 1955, three-year pattern bargaining began, making UAW wages and benefits the envy of many American – and overseas – workers. In 1964, the UAW won the principle of early retirement, and by 1970 workers enjoyed numerous benefits, including vacation pay, life insurance, and medical care. “Our contract covers dozens and dozens of provisions protecting the working conditions of our members”, summarized Bluestone. Any dispute at GM would have wider significance – something both sides knew as they headed to the bargaining table.Footnote 38

The Strike: 1970 Negotiations

A range of factors made the 1970 negotiations different. From the start, GM took a harder line. In February, CEO James Roche signalled the change of direction in a speech to the St. Louis Chamber of Commerce, asserting that GM faced the highest interest rates since the Civil War, along with rising wage and raw material costs. Roche also complained about declining productivity, as well as increasing absenteeism and a high number of unauthorized strikes – more evidence of grassroots restlessness. In 1969, he declared, GM had lost 13.3 million labour hours due to strikes, many of them wildcats. As a result, Roche claimed that the company's earnings had plummeted over the preceding five years. “We must restore the balance that has been lost between wages and productivity”, he warned. “We must receive the fair day's work for which we pay the fair day's wages […] Nothing less than the American future – the kind of country we will pass to our children – is at stake.”Footnote 39 While the UAW pointed out that GM remained very profitable, it was notable that its private data showed that the company's sales, profitability, and cash dividends had all fallen sharply since 1965.Footnote 40 Roche stuck to his line, telling stockholders later that the strike was “unfortunate and unnecessary”, caused by the UAW's unwillingness to accept the company's position.Footnote 41

By 1970, rising healthcare costs also led GM to adopt a tougher stance. When the two sides sat down, they did so at a time when medical and hospital costs were rising at twice the normal inflation rate. Leading the UAW's negotiating team, Bluestone reported that the “most significant demand” that GM made upon the union was for workers to pay for increases in healthcare premiums, a provision that would wipe out most of the 1971 cost of living allowance increases.Footnote 42

The company was also increasingly aware of a growing import challenge, another major cost pressure. In 1970, the union's research showed that over 1.32 million cars were imported into the US, with West Germany and Japan being the main contributors. At the time of the 1970 negotiations, imports were increasing rapidly.Footnote 43 The UAW noted that GM became more aggressive at the bargaining table in response to this influx, especially after the strike. “The attacks by General Motors Corporation have increased in intensity as the import problem has grown in intensity”, reported Bluestone in 1971. By this time, imports represented sixteen per cent of all US car sales, and GM insisted that the union had to do more to tackle the issue. “Management cannot carry the whole load”, summarized the company. “Meeting the challenges of the imports in the years ahead will require the all-out efforts of unions, management and employes.”Footnote 44

The company's harder line was a central cause of the strike. GM's increased assertiveness challenges the idea of a “political strike”, which is based on claims that after Walter Reuther's sudden death in a plane crash on 9 May 1970, Leonard Woodcock provoked the strike to strengthen his position. As a Wall Street Journal analysis put it, Woodcock – who had previously bid unsuccessfully for the UAW presidency – “needed a big victory to assure his political stability and re-election”. In The Company and the Union, Serrin also argued that Woodcock felt “pressure to prove himself” by striking GM.Footnote 45

Primary records, however, muddy claims that Woodcock lacked legitimacy. To be sure, Reuther's death – after twenty-four years in office – left a big vacuum, yet the union acted quickly to fill it. At an emotional executive board meeting on 22 May in Detroit, Woodcock was sworn in as president, following a narrow victory over Douglas Fraser. A key figure within the union, Victor Reuther – Walter's brother – endorsed Woodcock and the two men shook hands and embraced to a “standing ovation”. “I think Walter would be enormously proud and pleased by your choice and the manner in which it has been arrived at”, he declared. Victor Reuther was confident that Woodcock would carry on the “unique character” of the UAW, which did not just fight for “wage increases and good pension plans” but saw itself as part of the broader “struggle for human rights”. “The United States doesn't need just another union”, he noted. In response, Woodcock stressed unity. “Our great loss has tightened our ranks and I am positive will make us rise above our abilities”, he concluded.Footnote 46

The bargaining positions taken by the two sides were also largely adopted before Reuther's death. GM had already outlined its unprecedented cost pressures. The UAW's programme, meanwhile, was agreed upon at its convention in April 1970, while Walter Reuther was still alive. More than 3,000 delegates approved this programme.Footnote 47 At the April convention, the UAW laid out a comprehensive list of demands, including a “substantial” wage increase, restoration of the cost-of-living allowance without a “cap”, improvements to the Supplemental Unemployment Benefits programme, and “higher basic pension benefits”. It also sought to establish a dental care programme. Reporting on the April convention, the New York Times noted that a strike against GM was “more than a possibility”.Footnote 48

The union knew that it would face unprecedented corporate opposition. At the UAW's National General Motors Council in July, the tone was defensive. “This is the year, the hour, when we are going to be tested”, warned Victor Reuther. As well as GM's heightened cost sensitivity, Reuther pointed out that the union faced a hostile political and economic climate, with a Republican in the White House and an economy showing weakness due to the costs of the Vietnam War. At a “hard-working” three-day meeting, the first under Woodcock's presidency and Bluestone's co-directorship of the GM Department, the negotiating team was finalized. Although headed by Woodcock and Bluestone, the committee also included twelve rank-and-filers elected by the union's GM sub-councils. There were representatives from plants in the industry's heartland of Michigan and Ohio, as well as several other locations, including California and Georgia. “These are decisive negotiations”, summarized Bluestone. “The economic well-being of GM workers and their families depends on their outcome.” Bluestone also stressed the importance of local – and non-economic – issues, telling members that it was vital to secure “essential improvements in working conditions in plant after plant in the GM system”.Footnote 49

Transcripts from the negotiations showed that the company resisted the union's efforts to remove a cap – agreed in 1967 – on the cost-of-living allowance, and disliked efforts to compare the 1970 talks to those three years earlier. “We are negotiating a new agreement”, commented GM's lead negotiator, Earl Bramblett, in a bargaining session on 25 November, “no purpose can be served in trying to renegotiate past agreements”. Bramblett also termed the union's wage demands “high, much too high”.Footnote 50 The same month, Bluestone told the UAW's executive board that the strike came down to three “basic issues” at the national level. They were “(1) Bigger wage increase; (2) restoration of cost-of-living formula as matter of basic principle; and (3) 30 and Out”.Footnote 51 The union justified its demand for a pay increase on a number of grounds, especially the inflationary climate – in the early 1970s inflation, largely generated by the costs of the Vietnam War, was running at about six per cent a year.Footnote 52 There was also the precedent of settlements agreed by other unions, including a recent Teamsters package authorizing a forty-three per cent increase in wages and benefits over thirty-nine months. The UAW also quoted a pledge by GM president Charlie Wilson in 1950 – made in a speech to the National Press Club – that workers should receive “in advance a yearly increase in real wages”. Used to GM delivering on this, the union balked at its new parsimonious approach. This gap between labour and management expectations helped explain why there was so much labour conflict in the 1970s.Footnote 53

In many ways, cost of living was the key issue – as it was for many workers at the time. In 1967, when the UAW had agreed to cap the allowance at eight cents a year, the cost-of-living adjustment had not exceeded that for more than twenty years. In the late 1960s, however, inflation spiked as US involvement in Southeast Asia escalated, transforming the bargaining climate. “We had the Vietnam War-spiked inflationary period of the late 1960s, so we had to remove that cap”, recalled UAW vice president Douglas Fraser. As Bluestone explained, eliminating the restriction became a “top priority”, because increases above the ceiling that would otherwise accumulate in the cost of living had been promised to workers at the expiration of the 1967 contract. By the time of the 1970 negotiations, the auto workers’ average cost of living was twenty-six cents an hour, due to them under the 1967 agreement. As such, it was again prior commitments – more than the circumstances produced by Reuther's death – that dictated the UAW's position.Footnote 54

Thousands of Local Negotiations: The Strike on the Ground

At its heart, however, the 1970 GM strike was much more than the national battle that others have focused on. In addition to the national negotiations, which privileged economic matters, there were also scores of local negotiations where shopfloor issues took centre stage. “Often overlooked”, wrote Bluestone,

but of vital importance, is the fact that negotiations at the local level took place simultaneously with negotiations at the national level. Local agreements deal with working conditions, health and safety, protective clothing, seniority rights, transfer rights, shift preference and a host of other matters relating to the day to day in-plant welfare of the workers directly on their jobs. Thousands upon thousands of […] problems were resolved in these local negotiations.

Clearly, the strike was more than the battle for wage and benefit increases that predominated in the attention-grabbing national talks.Footnote 55

Other UAW leaders made similar points. Emil Mazey noted that local issues were at the heart of the strike, and many rank-and-filers were passionate about them. “Working conditions are something that you have to work at continually”, he stressed. “We had local strikes in addition to a national strike.” Illustrating this, workers in Norwood, Ohio, stayed on strike until February 1971 over local conditions, while those at the GM plant in Atlanta stayed out until late January. “We had a seven months’ strike in Norwood over working conditions”, recalled Mazey. “And we had quickie strikes on working conditions.” These walkouts were possible because UAW contracts allowed members to strike during the life of the agreement over local issues such as production standards, safety violations, or line speeds. All were sensitive topics.Footnote 56

From the beginning, local issues were integral to the strike. The UAW's files showed that, as of 23 September 1970, it had received some 38,358 local demands to present to GM, the vast majority (32,899) of which remained unresolved. Of these, only about 5,000 related to issues on the national table, leaving some 26,318 issues to be settled locally. The most common grievances were non-economic, covering what the union termed “working conditions” (14,950). In this large category, complaints were diverse. “Working conditions encompass the largest group of local demands”, related a union summary.

Demands have been submitted in 85 areas under this category. They include such things as absenteeism, shift schedules, vacations, work assignments, entertainment or recreation for employees, providing legal advice, additional wash-up facilities, nursery care for working parents in the plant, employes’ cars to be serviced and maintained at company expense, and health and safety.

Shopfloor issues, particularly the impact of new technology on workloads, produced many complaints. Concerns about production standards and the grievance procedure were also common – and showed that good wages and benefits were not enough for many overstretched workers. An amalgam of many local battles, the 1970 walkout was more than one strike.Footnote 57

GM sources confirm that local issues were at the heart of the strike. In a letter to stockholders on 26 October, for example, CEO James Roche related that in addition to the national settlement that executives were working on, “each plant must reach agreement on local issues”. He explained that although “intensive negotiations” were occurring on the local level, progress was “very slow”. Roche added that GM's goal was to produce a settlement that was “sound” for all parties involved; workers, customers, stockholders, and – reaffirming the strike's importance – the “nation's economy”.Footnote 58

Local issues had been building for some time, and often outweighed national ones. As the UAW documented, between 1955 and 1970, 14.9 million hours of work were lost at GM's plants due to a national strike (a brief stoppage in 1964), but a far greater number – 101.4 million hours – were lost to local strikes. In the years prior to the 1970 dispute, the number of local demands increased sharply, rising from 11,600 in 1958 to 24,000 in 1964 and 31,000 in 1967. In the 1964 contract talks, the national strike – itself over shop steward representation issues – lasted just ten days, but local strikes kept GM plants closed for a further five weeks. In 1967, moreover, there were strikes at sixteen GM plants and the final local settlement was not reached until seven months after the national agreement. Clearly, viewing the strike purely as a reflection of national bargaining is misleading.Footnote 59 Local demands, summarized a UAW document prepared for the 1970 negotiations, had become an “increasingly difficult problem in recent years”. A survey of members before the strike confirmed this, showing that many wanted to protest over grassroots concerns. A significant number of GM workers, for example, had negative feelings towards their jobs and did not regard their workplaces as “pleasant”.Footnote 60

Demographic changes informed these shifts. Like the Lordstown dispute, the GM strike reflected disaffection from younger workers, particularly at the shopfloor level. By 1970, GM's workforce was increasingly young. According to the UAW's records, in the Detroit area eighteen per cent of strikers were single, while a further twenty per cent were childless couples. The idea that virtually all GM workers were married with children was exaggerated; increasing numbers were young and rebellious.Footnote 61 UAW leaders were aware of these changes, and they infused the strike. “We have become a much younger union”, Fraser told the GM Council in July. “The values of our younger members are different. They are not going to submit to unsafe and dangerous working conditions. They are not going to go along with compulsory overtime.” At Chrysler, the UAW division that Fraser headed, forty-two per cent of members were under thirty.Footnote 62 In 1970, the UAW's push for stronger early retirement provisions reflected pressure from younger workers. As a detailed survey of older members before the dispute had found: “The non-retired workers interviewed reported a growing support of early retirement. Almost two-thirds felt that ‘older workers should retire early […]’ Only 3% disagreed strongly with the view that ‘older workers should retire early and make room for others’.” These older workers also complained about “working primarily with younger colleagues”.Footnote 63

Reflecting the industry's history, the vast majority of strikers were men. “Until now”, summarized Mary Salpukas in the New York Times in 1973, “G.M. has not offered many opportunities for women”. As late as 1965, there were no women enrolled at the General Motors Institute, and even in 1973 – following some effort to address the problem, driven by federal contractor regulations – they only comprised 4.6 per cent of the total. “I don't see any change in men's attitudes, and G.M. is run by men”, complained a female worker that year. In response, Laurence L. Vickery, GM's director of employment relations, admitted that there had been a “lack of attention” to women – and minorities – by the company, but claimed that managers had reflected “society as a whole”.Footnote 64 The UAW also mirrored these patterns, with change happening gradually. One union study from 1970 described the “typical” early retiree as a “married white male”, and the UAW went into the 1970 negotiations with an all-male bargaining team. In 1970, former Chrysler worker Olga Madar had become the UAW's first female vice president, yet she was the sole woman to sit on the executive board, the union's top decision-making body. Like the industry, the UAW remained male-dominated.Footnote 65

Launching the Strike

In early September, strike votes taken by the union, collated in their files, confirmed the strong support for a walkout. At the Chevrolet plant in Lordstown, Ohio – which would attract such attention two years later – ninety-six per cent of workers voted to strike. At a GM plant in Tarrytown, New York, the vote was 4,461 for to 233 against, while at Buick Motors in Flint it was an overwhelming 7,645 to 375. Across GM's sprawling empire – even in places not widely associated with car-making – the pattern was similar. At GM's large Lakewood plant in Atlanta, for example, the vote was overwhelming – 4,190 to thirty-seven. At the South Gate plant in Los Angeles, it was also strong (2,005 to 131). The Detroit plants reported similar margins. Many of those voting, moreover, did so on the basis of local grievances. As well as assembly plants, strike votes were also taken by suppliers in states as varied as Florida, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Oklahoma. The GM Parts Division alone had thirty-eight US plants.Footnote 66

On 14 September, the two sides engaged in a long day of final bargaining at GM's Detroit headquarters. As the Wall Street Journal reported, however, they made “absolutely no progress”. Both protagonists were “unyielding”, added the Washington Post, leading to a “glum mood”.Footnote 67 On 14 September, GM posted a message on plant bulletin boards, declaring that it would “continue to make every reasonable effort to arrive at a sound and fair agreement”. At the same time, the company told workers that as the contract had expired, they no longer had to pay union dues – and it would be ceasing all deductions.Footnote 68 As the contract ran out at 11.59 p.m. that night, Woodcock told the press that the company gave the union “no other choice” but strike. He added: “They've made offers and they're far from the reduced positions we have taken. And we have some substantial contract matters before us.” Denying its responsibility, GM blamed the UAW for the outcome.Footnote 69

Even at this critical juncture, however, little-known local agency was important. Taking matters into their own hands, workers at GM's plants in Oshawa and St. Catherines, Ontario, had begun wildcat strikes several days earlier, and these unauthorized stoppages spread to five US plants after Woodcock announced that GM would be the sole strike target. The wildcats again reflected a growing sense of dissatisfaction with conditions on the line, where workers, especially younger cohorts, sought a stronger voice over line speeds and decision-making – as well as better pay and benefits. On 14 September, workers readied for the strike by setting up soup kitchens in union halls, painting picket signs, and establishing picket line rosters. At GM's Technical Centre in Warren, Michigan, for example, a local 160 official promised that there would be twenty-four-hour picketing, supervised by “flying squadrons of pretty good-sized guys”. Workers’ investment was clear.Footnote 70

Throughout the strike, the UAW also ran educational classes that increased members’ involvement. Strikers attended day classes that were a substitute for picket duty, receiving instruction about the issues in the dispute. The classes also, however, covered broader issues, including labour history, economics, “major social issues”, and international labour solidarity. Overall, the UAW reported that the educational effort had achieved “excellent results in developing a better informed, more alert and concerned membership”. Many workers enjoyed the classes, illustrating that their investment in the strike was greater than most reports – focused on the picket lines rather than the classroom – realized.Footnote 71

The unauthorized strikes confirmed that the rank and file also set the pace. “Many workers jumped the gun by supporting wildcat stoppages before strike time”, summarized the Washington Post. Wildcats occurred in several plants, including a large Cadillac factory in Detroit where a group of young strikers – many of them African American – were interviewed by CBS News. “They figure they got us beat or something, General Motors”, commented one young black picketer. “We're going to show them that we mean business.” Others demonstrated that they were invested in the key issues. In particular, the cost of living adjustment was crucial, with strikers willing to stay out “until we get it”.Footnote 72 Retirement after thirty years was also very important (Figure 1). It was “one of the great issues that we really need”, commented an unnamed African American striker, not only to allow workers to retire from a demanding job, but so that they could “make jobs for a lot of people that is out in the street now and need jobs. I think that is one of the greatest (issues)”. Overall, summarized CBS News reporter Bill Plante, “the men on the picket line reflected the militant mood of many in the union”.Footnote 73

Figure 1. A picket line outside a Cadillac plant in Detroit, November 1970. The right for workers to retire with benefits after thirty years of service was particularly important to many rank-and-file.

© Tony Spina – USA TODAY NETWORK

For many strikers, the lengthy dispute brought significant hardship, but they were willing to endure it. Most existed on union strike benefits of $30 to $40 a week. On 30 September, two weeks into the strike, NBC national news reported that strikers were “beginning to feel the pinch”. “Forty dollars a week isn't much”, it explained. In Flint, Michigan, where 50,000 people worked for GM, the strike took $8 million a week out of the economy, and strikers described a stressful situation. “I'm awfully nervous just thinking about what might happen within the next four to five weeks”, admitted Larry Renshaw, who had nine children.Footnote 74 On 30 October, forty-six days into the dispute, NBC returned to the Renshaws and found that they were hurting; most of their savings gone, they relied on welfare to make ends meet. The food stamp programme, explained Renshaw, had been a “lifesaver”.Footnote 75 The UAW's records indicated that many strikers received public assistance, including food stamps, with a family of four qualifying for a payment of $132 after a month of unemployment. While the burden of the strike was considerable, strikers did not contemplate returning to work, expressing instead their determination to “start over”.Footnote 76

For the UAW, the financial burden was considerable. As well as strike benefits, the union paid costly medical, hospital, and life insurance premiums that were discontinued by GM when the contract expired. Leaders admitted that without significant outside support, the Strike Fund would be “depleted” by the end of November.Footnote 77 In late September, the executive board also authorized a fifty per cent pay cut for all staff, effective immediately. In addition, the board agreed that once the strike fund had run out, all staff – including officers – would receive “no pay”. Many other cuts were implemented, including a fifty per cent reduction in vacation pay and a moratorium on loan payments.Footnote 78 Woodcock, Bluestone, and other key staff also removed themselves from the UAW payroll the day the strike began. As Mazey recalled, the strike reflected “real antagonism”. Facing a company that made “scandalous profits”, the union was determined to prevail. The heavy investment – moral and financial – emphasized the strike's importance.Footnote 79

“God Bless You”: Mobilizing National and International Support

To prevail, however, also required support and publicity, something that the UAW understood well. They took the strike to national and international audiences, mobilizing significant levels of backing. Within the US, some of the strongest financial assistance came from the Rubber Workers, who raised $3 million, and the Steelworkers, who gave some $10 million.Footnote 80 Although the UAW was not part of the AFL–CIO, having left in 1968 following differences between Walter Reuther and George Meany, Meany still pledged the Federation's “full support” for the walkout.Footnote 81 In October, the UAW also established a National Citizens’ Committee to Aid the Families of GM Strikers, part of a “national effort” to mobilize support. The committee collected donations for strikers’ families and organized national advertising that featured “prestigious names”. It moved well beyond labour participation.Footnote 82 Highlighting this, a press release described the Committee's heads as “seventy-eight of the nation's most prominent leaders in business, labor, government, the arts, education, clergy and the civil rights movement”. Among them were prominent economists John Kenneth Galbraith, Leon Keyserling, and Robert Nathan. Wilbur Cohen, a former Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, led the Allocations Committee, which assigned aid to strikers’ families.Footnote 83

A range of other high-profile Americans took part in the Committee, a vital support. Retired Illinois senator Paul H. Douglas acted as chair, while other members included former US vice president Hubert Humphrey and civil rights leaders Coretta Scott King, Bayard Rustin, and Roy Wilkins. Also active were several US Senators – including Birch E. Bayh, Edward Kennedy, George McGovern, and Edward Muskie – and religious and community leaders.Footnote 84 They all saw the strike as an important battle, especially in holding giant corporations to account. As an NAACP leader put it, this was a fight “on behalf of the little people”.Footnote 85

The UAW had broader mobilization plans. At its special convention in Detroit on 23 October, Woodcock spoke of the Citizens’ Committee rallying “millions” of “decent Americans” to the strikers’ side. While some of the plans were a little ambitious, various initiatives followed – and clearly secured significant results. Through lesson plans sent to more than 250,000 members by the American Federation of Teachers, for example, countless US schoolchildren learnt about the strike.Footnote 86 Strike records also show that many everyday adults – including low-paid workers – responded to the Committee's work. One female nursing home aide from St. Louis gave $1 to the strikers – noting that she only made $1.55 an hour. An unnamed carpenter also sent in $1, adding, “I'm crippled in my left hand. This is all I can afford. God bless you!” Correspondents often stressed the strike's human impact. “It is difficult enough for a person to be out of work”, summarized a backer from Philadelphia, “the additional worry of feeding and caring for a family, paying off past debts, and planning for future arrangements should be shared by everyone concerned for the GM strike”. Reflecting similar sentiments, several women's groups – including the Inter-Racial Mothers’ Association of Dade County (FL) and the Emma Lazarus Jewish Women's Club – also sent in money.Footnote 87

The National Citizens’ Committee was especially effective at broadening the strike beyond the GM workers, who were overwhelmingly male, to their wives and families.Footnote 88 As Douglas put it, the Committee's goal was to ensure that “decent men and women will not have hunger and hardship govern the outcome” of the dispute. Assistance was distributed based on family need. As the Committee's records show, many families were helped through emergency payments. “The Atlanta Sub-Committee considered the plight of C.G.P.”, noted one example. “He has four children ages 7, 6, 5 and 4; his wife is pregnant, he faced eviction on December 26th owing $170 in rent.” The family was behind on furniture and car payments, had a sizeable bank loan, and were borrowing money to buy food. As a result, they were awarded $100. In another case, “R.C.”, a striker from Michigan, received $150 after his family of six had their food stamps cut off due to the strike.Footnote 89

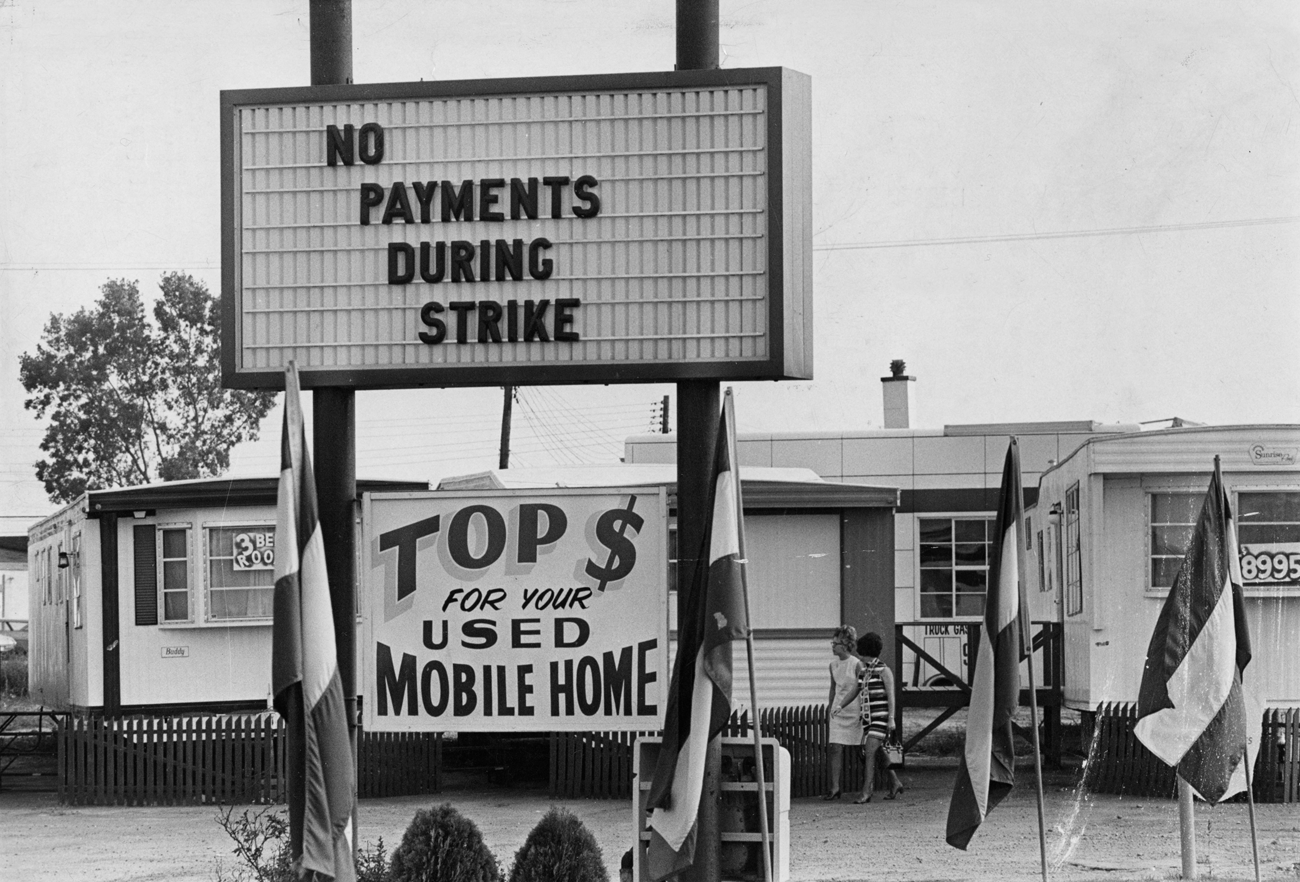

Other high-profile figures were mobilized. Many congressional representatives, including Ohio's Louis Stokes and Oregon's Wayne Morse, wrote in support.Footnote 90 Congressmen John Conyers, Charles C. Diggs, and William D. Ford helped organize the Michigan Citizens Committee to Aid the Families of GM Strikers, which carried out important work in the heavily affected state.Footnote 91 From the academic community, backing came from noted labour historian Philip Taft, who mailed in $100, and Pulitzer-prize winning scholar Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., who joined the Citizens’ Committee.Footnote 92 Community support was also notable. In several Michigan cities, including Detroit, Pontiac, and Saginaw, Motor City Prescription Centres provided free drug prescriptions to strikers’ families, while other businesses also provided support (Figure 2). Some national groups also spoke out. According to the Workers’ Defense League, the walkout was “a most important struggle for a decent standard of living and working conditions, not only for auto workers in General Motors but workers all over the country”.Footnote 93

Figure 2. A mobile home dealership in Flint, Michigan, offered terms that required no payment until after the strike.

ANP/Redux The New York Times/Gary Settle

The level of international mobilization was also noteworthy. Much of it was the work of Victor Reuther, the former International Affairs Director for the Congress of Industrial Organizations. Received at the start of the strike, one telegram from Moscow expressed support for the UAW's “legitimate demands” on behalf of “millions [of] Soviet engineering workers”.Footnote 94 Despite the Cold War, many other citizens behind the Iron Curtain were mobilized. Workers in the German Democratic Republic, for example, followed the strike with a “keen interest”. In an 18 September telegram, the GDR's 1.4 million-member metalworkers union expressed “full solidarity” with their American counterparts. In this polarized era, it was unusual for a strike to cross the ideological divide. These unions recognized the importance of defending labour rights at the world's biggest corporations – even though the degree of state control over unions in the DDR, and other Communist nations, makes it difficult to fully gauge shopfloor sentiments. The leaders of these unions, however, were clearly mobilized. As the dockworkers’ union from Pyongyang, North Korea – writing in “firm solidarity” – put it, the UAW was fighting “exploitation and oppression by monopolies”.Footnote 95

Workers in Western Bloc countries were also mobilized. On 21 September, the UK's large Transport and General Workers Union expressed its full support. Two days, Australia's Vehicle Builder Employees’ Federation wrote that it was “very concerned” by the “forced strike”. It offered “any assistance” possible. Japan's 240,000-member telecommunications union, Zendentsu, was also sympathetic, expressing its “full solidarity” with the American workers’ “just struggle”.Footnote 96 Again, many overseas workers admired the UAW's courage in taking on a corporation as big and powerful as GM. The strike, noted Yitzhak Benaharon, the general secretary of Israsel's Histadrut, had “served as an example and inspiration to workers and labour movements the world over”. The struggle, added Ivar Noren of the Geneva-based IMF World Auto Councils, was “significant for labour everywhere”.Footnote 97

Reflecting this, overseas workers also undertook sympathy actions. At Fiat's large plants in Italy, metal unions distributed 59,000 copies of a leaflet about the dispute, expressing support for the UAW. Venezuela's Fetrametal union, meanwhile, cabled its support of the strike against the General Motors “consortium”, promising that this backing could “be translated into practical terms in the event that circumstances of your struggle demand it”.Footnote 98 Highlighting similar sentiments, the Industrial Union of GM workers in Chile ordered a twenty-four-hour walkout on 1 October in support of their US counterparts, notifying “all national and local media” about the protest.Footnote 99 Among the other workers to express solidarity – and their willingness to act on it – were Colombian steelworkers, Argentinian autoworkers, and Hungarian engineers.Footnote 100

Powerful global labour federations also got involved. They included the Brussels-based World Confederation of Labour and South Africa's Confederation of Metal and Building Unions, who both expressed strong support. These proclamations reflected Reuther's efforts.Footnote 101 On 16 October, for example, Reuther travelled to Switzerland to address the Central Committee of the International Metalworkers Federation. “We do need your help and solidarity if we are to win this struggle”, he asserted. In response, the Federation, which represented 11 million workers in over fifty countries, called on IMF unions “in all parts of the world” to “take the necessary steps to prevent General Motors from utilizing its production facilities in other countries as a basis for undermining the strike”. In October, the UAW also received a confidential memorandum from the International Transport Workers Federation. Alerting all Asian, European, and Latin American dock and railway workers to the strike, it requested “appropriate action” in response.Footnote 102

The strike also received international press coverage. In one detailed editorial, the London Times called the UAW a “pioneer” in “international union cooperation”. The strike, it noted, built on previous UAW efforts to build links abroad, especially at GM, the biggest American-owned international company in the world. In 1968, American officials gave evidence for their Australian counterparts at an arbitration dispute with Holden, GM's Australian subsidiary. The unions won. Through the International Metalworkers’ Federation, the UAW had also built links for decades. Under Walter Reuther's leadership, the UAW had organized Canadian auto workers, winning the first binational agreements in the auto industry. In 1970, Canadian and US auto workers struck together.Footnote 103 Other international papers followed the dispute and were passionate about it. “This is really a strike!” summarized Argentina's La Vanguardia.Footnote 104

For workers in other countries, the UAW was important because it delivered path-breaking wages and benefits to its members, and did so through the collective bargaining process. La Vanguardia, for example, was impressed that the strike could be successful without “plant take-overs” and the “destruction of the workplace”, which were commonplace in Argentinian labour disputes.Footnote 105 In the battle with GM – a company with a major international presence – overseas workers also saw the UAW as fighting for workers everywhere, demonstrating that they had rights even at the most powerful corporations. This was especially true for GM workers abroad. In 1970, according to the UAW's research, GM had facilities in a wide range of countries, including Australia, Brazil, Chile, Great Britain, Mexico, South Africa, Venezuela, and West Germany. Some of GM's most extensive overseas operations were in Britain, where it had nine plants.Footnote 106 “Since GM is a worldwide corporation with operations in over 25 countries”, summarized Victor Reuther, “it is understandable that the unionized workers employed by GM in other lands feel an identity with the struggle of our own members for social and economic justice, and they stand by our side in that struggle”.Footnote 107

Messages illustrated Reuther's point. In September, West Germany's large IG Metall union praised the UAW for taking on the “Almighty GM Corporation”. “We are presently faced with the similar situation here in Germany”, added workers from Opel, GM's large German division.Footnote 108 Others explicitly saw the strike as a talismanic struggle. “Ten million organized automotive and related metalworkers in 60 countries throughout the world join in solidaritz with your earnest steps to force giant world companies like GM to accept responsibility to workers on their pricing, production and labor relations policies”, wrote the International Metalworkers’ Federation. For global labour, this story was compelling and dramatic.Footnote 109

Winning the Strike: The Economic Impact

The international support lifted spirits at Solidarity House. Any strike also had to be won on the ground, however; a big task. GM's size was the main reason that the UAW had not attempted a national strike since 1945. Smaller strikes had occurred, but these were not to establish an industry wide pattern, one of the aims of the 1970 walkout. In 1970, GM was not just the biggest automaker; it was also the largest employer in the world, and one of the biggest military contractors.Footnote 110 According to a UAW analysis, GM's A.C. Spark Division alone had more than 300 government contracts, while the Delco Radio arm had “critical US Government classified contracts”.Footnote 111

The stakes were high. “The total contribution of GM to the economy is enormous”, summarized Laurence G. O'Donnell in the Wall Street Journal at the start of the walkout. GM sold nearly $20 billion worth of goods in the US annually, and more than $24 billion worldwide. Its total payroll was $8 billion a year, and its 1.3 million stockholders received over $1.2 billion in dividends in 1969. In 1970, according to the US Commerce Department, the company accounted for 2.3 per cent of America's economic output.Footnote 112

Despite the challenge, strikers rose to their task. Helped by the strike fund, the Citizens’ Committee, and the labour movement, they crippled GM's operations, a significant outcome. As even the Wall Street Journal acknowledged, the strike had a “staggering impact”. According to GM's own figures, the strike cost it $90 million of sales a day. The ripple effects were enormous, especially as some 39,000 companies supplied GM with goods, including machinery, steel, and tyres. As soon as the strike began, suppliers laid off thousands of employees.Footnote 113

Strike records document the economic impact. Using data from Ward's, a respected industry publication, UAW research staffer Emily Rosdolsky found that in the third quarter of 1970 sales from GM's US plants dropped over forty per cent compared to a year before. From the company's Canadian plants, sales fell 63.5 per cent. In the week ending 26 September, for example, GM's US plants had produced 96,214 cars in 1969, but in 1970 they made none. Outside North America, sales from GM's plants also fell.Footnote 114

Several other sectors were also hit. Prior to the walkout the steel industry, for example, had been enjoying what the Wall Street Journal termed a “brisk autumn upturn”. The strike, however, delivered a “rude jolt”. During the walkout, steelmaker Jones and Laughlin laid off 4,000 workers in the US and Canada. Analysts warned that the strike, especially if it continued for long, would cause widespread damage. “Now the economic recovery is questionable”, summarized one steel analyst in October.Footnote 115

The Deal

As the strike wore on, the economic pressure told. The walkout disrupted the start of the 1971 model year, which was vital because GM was introducing its new small car, the Vega. Much was riding on the model, which was designed to compete with successful compact imports, particularly from Datsun, Toyota, and Volkswagen. Chrysler at this time lacked a small car, but the Vega – along with the Ford Pinto – had just been launched.Footnote 116 Still, for several weeks GM held firm, especially over its health care changes. Negotiations over this issue were “largely responsible for holding up the strike settlement”, reported Bluestone. As the economic impact increased, however, a breakthrough came.Footnote 117

Tentatively agreed on 11 November, the national settlement gave the UAW a range of concessions. Prior to the strike, the average wage of auto workers was approximately $4.03 an hour. According to the union's research department, the new contract increased these wages by 18.5 per cent over three years (or 5.8 per cent a year), while total costs rose 19.6 per cent (or 6.2 per cent annually). The union also persuaded GM to drop demands that limited the number of grievances that workers could file and the time that local union officers could spend on UAW business during company time, concessions that were important to rank-and-filers. While the UAW gave up its demand for company-paid dental care, it fought off increased health insurance premiums and eliminated the cost-of-living ceiling, both clear wins. It also resisted the productivity gains that GM had sought. As the Wall Street Journal acknowledged, the UAW “emerged stronger” from the walkout. The contract, thought one Detroit reporter, was “sensational”.Footnote 118

UAW leaders were delighted. Addressing the executive board, Emil Mazey called the settlement a “tremendous victory”. GM, he noted, had originally offered a wage increase of twenty-six cents an hour but the union had secured fifty-one cents. Winning the cost-of-living factor was also “outstanding”, even though it is worth noting that implementation was delayed by a year. “This was a real emotional issue and a real issue”, exclaimed Mazey, “and although there is some delay the first year, we have regained it”. On the early retirement issue, the UAW proclaimed, “a tremendous amount of progress”.Footnote 119

Tellingly, GM acknowledged the union's gains. During the strike, CEO James Roche had told stockholders that GM workers were “among the very small percentage of American workers who are protected automatically by periodic wage adjustments against increases in the cost of living”. Despite this, the union had won an extension of the programme after workers expressed concern about the “recent rapid rise in prices”. Executives also expressed strong opposition to the “thirty-and-out” demands. “GM considers it undesirable to encourage experienced workers to retire when they are in the prime of life”, claimed Roche. Overcoming these objections, the UAW had secured the early retirement provisions, which were important to many workers.Footnote 120

There were other advances, including improved hospitalization benefits, better safety provisions, and extended disability benefits. At more than ten pages long, GM's settlement proposal showcased a wide range of improvements.Footnote 121 Not surprisingly, the two sides differed in their view of whether the settlement was inflationary, with the UAW stressing GM's core profitability and market dominance. For the 1971 model year, however, GM hiked prices by six per cent; in response, the union stressed that this was in line with inflation and broader trends.Footnote 122 Following endorsement by the GM conference, it took a week for workers across the country to vote, meaning that the strike did not formally end until 5 pm on 20 November.Footnote 123

In a wider context, the settlement was particularly important because it was pattern-setting, quickly copied by Ford and Chrysler. As Douglas Fraser reported from the Chrysler negotiations in January 1971, “the GM and Ford collective bargaining pattern had been achieved by production and maintenance workers”. Given the size of the Big Three, these gains were critical; they directly employed more than one million workers in the US and Canada, plus many more at suppliers.Footnote 124 After some delay, the settlement also provided the basis for agreements in Canada, where the principle of wage parity was preserved. By the summer of 1971, the GM settlement had also been largely copied by the can and aluminium industries, and was being replicated in the copper and steel sectors. It also led to gains for workers in many other industries. “Fortunately”, summarized Woodcock, “we were able to negotiate a sound, progressive and non-inflationary agreement with General Motors, one that we believe will be beneficial to the workers and their families, to the corporation and to the nation”.Footnote 125

Reaction to the settlement was wide-ranging, re-affirming the strike's importance. At the UAW's Detroit headquarters, congratulatory messages poured in, with some coming from overseas.Footnote 126 Within the US, Senator Ralph Yarborough was one of several high-profile politicians to write. Sending his “warmest congratulations”, Yarborough praised the UAW for prevailing against “the giant of them all”. In a similar vein, Senator Birch Bayh praised a “stunning” breakthrough, while Latino activist Cesar Chavez called it a “great victory”. Even AFL–CIO leader George Meany, who was famously gruff, called the settlement “splendid”.Footnote 127 Among other prominent figures to praise the agreement were progressive lawyer Joseph Rauh, Motown musician Hal Davis, and civil rights icon A. Philip Randolph. “Congratulations upon your magnificent and monumental victory in your negotiations with the giant General Motors Company”, summarized Randolph.Footnote 128

After the Deal: The Ongoing Local Fight

The strike, however, did not end with the national settlement. Many local issues needed to be addressed, generating ongoing activism. Often, grassroots issues drove events at the top – changing significantly how the strike has been viewed until now.

Highlighting the limits of seeing the strike purely as a national struggle, by 11 November there had been eighty-five local settlements but seventy “non-settlements”. “Big population in some of these locals like Buick and Cadillac which are not settled”, Woodcock reported. As Bluestone told the executive board, local autonomy and restlessness were significant strike issues, and they continued after the national agreement.Footnote 129 Also in November, the New York Times reported that there were many dimensions to the strike, and they were often unresolved. Apart from plant level issues – ranging from seniority grievances to demands for better parking – skilled workers in many locations were also protesting over GM's push to use more outside contractors.Footnote 130 Some UAW leaders expressed frustration with the intractability of local issues. “At some point we will have to tell them that they will not get some of these demands”, summarized regional director Marcellius Ivory. Despite this, as late as 16 December, two local unions were still engaged in strikes for agreements. Leaders related that these walkouts reflected “local issues”.Footnote 131 Even in places where settlements were made, issues of workloads, safety, and absenteeism remained prevalent.Footnote 132

Reaffirming the strike's diversity, the national settlement also did not apply in Canada. At GM Canada's seven plants, 23,000 workers continued to strike, demanding that wage parity between US and Canadian workers – which had been achieved in the last agreement, following a seven-week strike in Canada in 1967 – be reinstated. In 1970, the company's wage offer was worth less in Canada because of a variation in the cost of living. At the start of the strike, average pay for GM assembly line employees in Canada stood at $3.59 an hour, plus 19 cents cost of living allowance, compared to $4.03 in the US and the higher cost-of-living allowance.Footnote 133 Canadian workers showed particular militancy, having also led the wildcats that precipitated the overall strike call. As Toronto's Globe and Mail reported, the 1970 strike “hit early in Canada”, where workers in Oshawa, Ontario, and Ste. Terese, Quebec “ignored directives from union officials to stay on the job”. The pension demands also looked different in Canada, where the UAW had to modify its contracts to the Canadian pattern of federal old age security pensions and the Canada Pension Plan. “We can't track the US on this issue”, noted Dennis McDermott. “We're asking for $500 [a month] and 30 and out, but the mechanics will have to be worked out differently.” In the end, the strike lasted ninety-four days in Canada (compared to sixty-seven in the US), with most Canadian workers not going back until just before Christmas.Footnote 134

To be sure, the union could have done more to address local issues, both in the US and Canada. In 1970, key issues included workers’ concerns about production decisions and vehicle quality, as well as their increasing sense of alienation. As scholarly critics have highlighted, in the post-war era the UAW concentrated on winning pay and benefit increases rather than influencing management decisions and giving workers more power on the job.Footnote 135 The union's papers, however, show that it tried to step into these areas but faced dogged resistance from GM, which – like most American businesses – fiercely protected its “right to manage”. In the early 1950s, when fuel was cheap, America was booming, and big cars were in the ascendancy, the UAW pushed the Big Three, and especially GM, to take small cars seriously, but the companies resisted. In the years that followed, the union brought up the issue again, but made “no impression”. By the time the Vega was introduced, GM was playing catch-up. As Kevin Boyle has shown, moreover, the UAW consistently tried to promote “democratic economic planning and an expanded welfare state” but was constricted by “political, policy-making, and institutional structures” that limited their effectiveness, especially a Democratic Party that privileged compromise over reform.Footnote 136

As this article has shown, it also important to realize that even “national” battles were infused by local issues, most of them non-economic. As the story of the 1970 strike demonstrates, there was more than one strike, and the dispute meant different things to different participants. Through the gains made in the 1970 strike, moreover, the UAW did address some important local issues, particularly in winning stronger pre-retirement and cost of living protections.Footnote 137 UAW leaders also hoped that the 1970 settlement would allow them to have a stronger voice over management decisions, including about which cars were built. “Down the road I believe our Union and other unions will out of necessity move toward demanding the right to participate in these kinds of decisions that currently are unilaterally made by management”, declared Bluestone in 1971. The UAW also saw collective bargaining as linked to broader activism, as without strong contracts the union would struggle to be a meaningful social and political force.Footnote 138

Many GM workers, moreover, were proud of their role in winning the substantial breakthroughs that came from the strike. “From that strike in ’70 ‘til the ’80s, we made a lot of gains”, recalled Al Benchich, a former striker from a GM plant in Detroit. In 1973, the UAW built on the strike's gains, adding what it called “significant improvements” in the early retirement and pension programme, as well as other advances.Footnote 139 In that year, Emil Mazey described the UAW as the “most progressive union in the country”, insisting that it would “continue” to fight for a bigger decision-making role. While Mazey was a UAW official, rank-and-file investment in the struggle was real – as were their gains. Across North America, workers emerged from the strike with hope. By 1975, US auto workers made $249.53 a week, up sharply from $56.51 in 1947 (in stable dollars). Historian John Barnard called them the “best paid blue-collar workforce in the world”.Footnote 140

The Strike: Aftermath and Conclusion

Workers would enjoy the gains won by the strike for decades and be proud of what they had fought for. More than fifty years later, this is worth remembering. The strike – its issues, size, and impact – mattered.

In the 1970s, however, imports made unprecedented strides, slowly pushing GM – and the UAW – onto the back foot. From the 1980s on, the establishment of non-union plants by foreign-owned automakers in the US exerted further cost pressure, leading to job losses and concessionary bargaining at the Big Three. In 1970, few could have anticipated the establishment of these plants, which lowered costs by locating in the lower-wage South and steadfastly avoiding unionization, unheard of in the industry at the time.Footnote 141 Although GM tried to hit back against foreign competitors, its small cars, especially the Vega, were never a success. “US-built small cars seem to be having difficulty displacing the imports”, admitted UAW staffer Carrol Coburn in April 1971. Big Three contracts began to go backwards, with workers fighting what Benchich termed a “rearguard action”.Footnote 142 Between 1970 and 1998, employment at the firm more than halved, from over 400,000 to around 200,000. When GM workers struck again in the fall of 2019, the company employed fewer than 50,000 hourly workers.Footnote 143

Partly because of the industry's subsequent decline, the 1970 strike has been overlooked, lost to history. It is important, however, to tell the history of the strike as it unfolded, to capture its “staggering impact” on America – and beyond. As CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite put it, this was a strike that “threatened the nation's economy”. It is a story that should be at the heart of emerging scholarship on the 1970s, especially as it encapsulates the broader labour militancy of that time.Footnote 144 The argument that the dispute lacked drama also elides the experience of the strikers, who endured hardship to take on a corporate behemoth. Ultimately, there could have been no strike without them. “General Motors workers”, summarized Mazey, “will be making the maximum sacrifice in establishing the 1970 collective bargaining pattern in the auto industry”. In key respects, it was workers who carried out the strike, rather than the UAW leaders emphasized in existing accounts. Like many workers around the globe in the 1970s, GM's rank and file fought hard and made important gains.Footnote 145

In many ways, this was a “gallant” struggle, with a drama of its own. It is a story that mattered – nationally, globally, and, above all, locally.Footnote 146 The largest industrial union in the country, the UAW had some 1.4 million members. The strike was a fight for all of them, and every member paid extra dues until its objectives were achieved. As a UAW analysis concluded, although this was a “costly struggle”, it strengthened the union – and not just because of the economic gains that resulted. There were also palpable psychological advances that reverberated for years afterwards. “The strike”, explained Bluestone in 1971, “was good for the soul of our Union. Our entire membership rallied behind the General Motors workers and closed ranks. We are stronger today as a Union by reason of the struggle – and prouder”. Reflecting on the dispute, Douglas Fraser also remembered mobilization and drama. “A strike against General Motors isn't just a strike,” he concluded, “it's a crusade.”Footnote 147