Introduction

Between the 1960s and early 1990s, Tanzania provided numerous liberation movements with assistance in the form of shelter, land, material resources, office space, diplomatic support, military training, and access to local and global networks.Footnote 1 This stands out from support provided by other countries on the African continent for both its substance and its longevity.Footnote 2 Such a commitment over several decades is inconceivable without popular support. In this vein, politicians encouraged Tanzanian citizens to practice solidarity with other people struggling against colonialism and apartheid, and some embraced this identity. The journalist Godfrey Mwakikagile, born in 1949 and a teenager in the 1960s, remembered that “we were on the frontline of the African liberation struggle and should be ready to defend our country, anytime and at any cost, and be prepared to fight alongside our brothers and sisters still suffering under colonialism and racial oppression anywhere on the continent”.Footnote 3 Anthropologist Richard A. Schroder has dubbed such memories, and the feelings of pride associated with them, “frontline memories”.Footnote 4 This “frontline” was not only physical, through the borders Tanzania shared with countries still under colonial or white minority rule (as in the case of other “frontline states” in Southern Africa), but also imagined in a broader regional, continental, and global sense, even after the collapse of the Portuguese empire and the independence of all neighbouring countries up to 1975 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Independence and end of white minority rule in Tanzania and surrounding African countries.

This article argues that the ideal of virtuous citizenship in post-colonial Tanzania transcended the national-territorial framework through a broader transnational ethos of solidarity along anti-imperialist lines. It discusses the emergence, reconfigurations, contradictions, and contestations of a political subjectivity that can be termed frontline citizenship, that is, a political culture of Pan-African and anti-imperialist solidarity that placed Tanzanian citizens at the vanguard of these struggles through their engagement in symbolic and material practices. As Christine Hatzky has shown for the case of Cuba, for instance, ordinary citizens enabled and enacted, embraced and contested, and thereby also influenced state-sponsored solidarity regimes.Footnote 5 Still, ordinary citizens have often been relegated to the sidelines in the growing body of elite-focused histories of anti-colonial liberation struggles, on the one hand, and the historiography of refugees, on the other.Footnote 6

Recently, the traditional distinction of solidarity regimes through a Cold War lens as being either predominantly state- or society-led, top-down or bottom-up, has been challenged. It is true that, in liberal Western countries, new social movements of anti-imperialist character challenged ruling governments; yet, (some) governments also came to support anti-colonial organizations and causes first embraced by civil society groups.Footnote 7 In Communist-ruled countries in Eastern Europe and East Asia, anti-imperialist solidarity was part of the regimes’ proclaimed raison d’être and a proclaimed duty of socialist citizens; solidarity has thus often been understood as imposed from above.Footnote 8 Against this view, Péter Apor and James Mark have argued that solidarity in Eastern Europe “extended well beyond the state, deep into intellectual and popular cultures, and was capable of bearing unorthodox political meanings” with which ordinary citizens challenged Communist elites.Footnote 9 Solidarity regimes in one-party states in Africa have received less attention thus far, but while the above insights may also apply, one important point of distinction was the combination of hospitality and proximity. In Tanzania, a non-communist but (especially after the 1967 Arusha Declaration) proclaimed socialist country, liberation movements were a constant presence in the country, whereas citizens of Western and Eastern European states engaged in predominantly symbolic and (physically) distant practices of solidarity.Footnote 10 In Tanzania, as Andrew Ivaska and Maria Suriano have shown, hospitality and living in shared spaces enabled a kind of “convivial solidarity” that bequeathed strong transnational bonds of support – but also tensions.Footnote 11

The relation between national and transnational processes, which was, in many ways, mutually constitutive, deserves still more scrutiny. Adom Getachew's important argument that anti-colonialism constituted forms of “world-making” beyond the building of nation states needs to be complicated by asking how the making of an anti-imperialist world was not only an elite project of intellectuals and postcolonial political leaders, such as Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere, but also one of (and for) ordinary citizens.Footnote 12 This sheds light on how anti-imperialist world-making and state-building reinforced or contradicted each other as they were fused in various mechanisms of mobilization, including mediascapes, education, and newly established institutions.Footnote 13 These made up a solidarity regime through which citizenship – understood as belonging to a certain community (of Tanzanians) – was linked to an identification with a broader communitas defined by shared sentiments and motives of anti-imperialist non-alignment rather than locality, race, or geography.Footnote 14

In this broadened view, Tanzania's political culture of frontline citizenship did not just grow “naturally” from nationalist struggles against British rule and the transition from colonial subjecthood to postcolonial citizenship, nor was it solely a result of top-down initiatives and speeches by Nyerere, the country's leader from independence in 1961 to 1985. During his presidency, the ideal of “virtuous” and “patriotic citizenship”, as discussed by Emma Hunter, Marie-Aude Fouéré, James R. Brennan, and others, projected the ideal Tanzanians as development-minded and productive nation-builders, modern but also egalitarian, frugal, self-reliant, and preferably rural.Footnote 15 This was, in the words of Priya Lal, a “spirit of socialist nationalism”,Footnote 16 rather than socialist internationalism. This article highlights that practices surrounding citizenship in Tanzania still had significant transnational dimensions, evident in a dynamic solidarity regime that was tied to anti-imperialist struggles for national sovereignty and freedom from white minority rule rather than socialist traditions of proletarian internationalism.

Based on multi-sited archival research, contemporary print publications, secondary literature, “frontline memories” of Tanzanians, and testimonies of former exiles, particularly from South Africa's African National Congress (ANC), the article discusses institutions through which the one-party state fostered, but also channelled and disciplined, transnational solidarity practices. It did so increasingly from the mid-1960s onwards, when other political parties and independent trade unions were banned and a new generation of solidarity-minded youths embraced an ethos of global solidarity informed by militant anti-colonialism and Third Worldism. Going beyond a national lens, the article shows that the state–citizen relationship intersected with initiatives of liberation movements hosted in Tanzania since 1961. In the final sections, the article discusses the gendered and generational character of the solidarity regime, the contestation of material solidarities, and the partial decline of the discourse of frontline citizenship.

Becoming Part of Nation-Building: Liberation Movements in Postcolonial Tanzania

The durable ethos of “frontline citizenship” in Tanzania cannot be accounted for only by the geographical proximity of colonial and white supremacist regimes and shared histories of struggle.Footnote 17 The longevity and robust, albeit ambivalent and contested, nature of anti-imperialist transnational solidarity must be attributed to multiple factors, similar to what Clinarete Munguambe has shown for Mozambicans’ solidarity with Zimbabweans.Footnote 18 Practical solidarity with liberation movements from other territories began well before the independence of mainland Tanzania in December 1961, mostly in a regional register with Pan-African overtones. Several parties, including Nyerere's Tanganyika African National Union (TANU), began to formalize their cooperation in the Pan-African Freedom Movement for East and Central Africa (PAFMECA) in 1958 to speed up the process of decolonization in the region.Footnote 19 When Tanzania became the first country in the region to attain independence in 1961, numerous liberation movements, most of which originated from Southern Africa, were given (though sometimes also denied) permission to establish offices in Dar es Salaam. By the mid-1960s, the ANC and other organizations also began running military training camps in rural areas.

Tanzania's unanticipated centrality and Dar es Salaam's evolvement as a “hub of decolonization” were based not only on bilateral relations with anti-colonial movements, but also on the crystallization of multilateral, Pan-African support structures.Footnote 20 In 1963, the newly founded Organization of African Unity (OAU) established the African Liberation Committee (ALC), headquartered in Dar es Salaam, in order to support anti-colonial struggles on the continent. The ALC channelled international aid from Africa and beyond to recognized liberation movements and thus played a crucial role in the survival or demise of individual organizations.Footnote 21 In contrast to authorities in Ghana, Egypt, or Algeria, Tanzanian elites did not wholeheartedly embrace this centrality, experiencing and fearing negative consequences. These included diplomatic ruptures with the UK, the US, and West Germany, all of which were also major donors, over issues of decolonization and sovereignty in the mid-1960s, and threats as well as subversion from nearby Portuguese Mozambique, Rhodesia, and South Africa. In the mid-1960s, Tanzanian leaders explored options to have the headquarters of the ALC transferred to Zambia or another country – without success.Footnote 22 Communist and anti-communist propaganda and plots endangered non-aligned Tanzania's fragile sovereignty. The resulting atmosphere of suspicion and outright “siege mentality” were a symptom of Cold War tensions combined with the country's location at the frontline of decolonization.Footnote 23 At the same time, however, international powers interested in influencing regional politics had to court Nyerere. Communist states in particular relied on Tanzania as an entrepôt for translating their claims of anti-colonial solidarity into material flows. Soviet weapons, tinned food from East Germany, and military advisers from China all had to pass through Dar es Salaam to reach guerrilla camps further upcountry.

Tanzanian authorities channelled most of these resources and decided on the granting of refugee status, residence permits, passports, and other essential aspects of exile politics. For this reason, leaders of liberation movements sought to create goodwill among key groups such as politicians and journalists, but also the broader population. The repercussions of this were particularly felt in the country's capital, Dar es Salaam. George Roberts has argued that liberation movements’ activities, including “press coverage and speeches at rallies or at the university[,] instilled the city's politics with a militant anti-imperialism” that “extended far beyond their Nkrumah Street offices”.Footnote 24 This was not a straightforward process. The character and effect of activities depended on Tanzanians’ willingness to allow and embrace such militancy. One also has to acknowledge that the appeal of various liberation movements differed drastically according to varying strategies, ideological preferences, and ethnic affinities, among other factors. While some organizations emerged in diasporic contexts in Tanzania (or elsewhere), others were forced into exile and had little footing in the country.

The latter was the case with the South African ANC, a movement with long-established structures and close links to the South African Community Party (SACP). It had access to resources from both inside and outside South Africa, but it still had to invest much in building up the “external mission” when it was banned by the apartheid regime in 1960. The ANC's legitimacy was challenged through the rivalling Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) and the understanding, widely shared in Tanzania and other host countries in sub-Saharan Africa, that liberation struggles should primarily be led by (and for the benefit of) black Africans. Following his tour of independent African countries in 1962, which included a conversation with Nyerere in Dar es Salaam, Nelson Mandela famously noted that the ANC's policy of non-racialism needed some “cosmetic changes” to be “understood” by other African leaders, many of whom preferred the PAC.Footnote 25 Many black Tanzanians looked upon the ANC with suspicion for its non-racialism, the role white communists played in the organization, and a supposedly weak commitment to armed struggle in the mid-1960s.Footnote 26 The ANC perceived unpopularity in broader circles as a problem. When the ANC opened its office in Accra in 1965 – relatively late in comparison with the many other organizations flocking to Nkrumah's Ghana – the new representative Joe Matlou wrote to Oliver Tambo in 1965 that there was “still a solid layer of hostility to-wards [sic] the A.N.C. in most of the people here”.Footnote 27 Measures to improve relations in Tanzania were taken shortly after the first opening of the office in Dar es Salaam in February 1961, nine months ahead of independence, when Nyerere's TANU had already assumed responsibility for internal government.Footnote 28

One of the ANC's ways to create closer ties with the government in Dar es Salaam was to recruit medical professionals from South Africa – with a first batch of twenty nurses arriving at independence in December 1961.Footnote 29 This brought South African medical workers into the fold of the ANC, but it was also deemed an “expression of solidarity” with Tanzania and “a present to Nyerere” as the country faced a severe shortage of personnel upon independence.Footnote 30 The nurse Mary Jane Nobambo Socenywa, who arrived in Dar es Salaam in 1962 and would stay for over three decades, remembered that the arrangement pleased TANU leaders but was not greeted with enthusiasm by her new co-workers. South African arrivals were caught in the middle between white nurses “packing their luggage” as they “did not want to work for a black government” and Tanzanian nurses who “thought we were taking posts that rightly belonged to them”.Footnote 31 In the wake of independence, when citizens hoped that “Africanization” would finally open the path to higher and better-paid positions denied to them during British rule, the recruitment of South Africans was seen by some as a setback. According to Socenywa, “people used to call us waKimbizi [sic], refugees who ran away from their own country”, but “the government got rid of all the people from the administration who were against us”. Authorities tried to instil an attitude of kinship, teaching Tanzanians that “‘[t]hese are your own people from South Africa. […] You should not be xenophobic because these professionals will teach you the same skills whites would have taught you’”.Footnote 32 This was indicative of a broader struggle over meanings and burdens of solidarity. Many exiles refused the slightly derogative Kiswahili label wakimbizi (refugees), despite the access this category might have given to resources of humanitarian relief agencies, as this portrayed them as passive recipients of aid or an economic burden on Tanzanians’ shoulders. They preferred to be seen as freedom fighters (wakombozi), as agents in a common struggle for liberation.Footnote 33 “Freedom fighter” was also the term that Nyerere and other leading politicians tried to promote for decades, in line with the Pan-African argument that independence was incomplete as long as other countries were not yet liberated. Liberation elsewhere and regional cooperation were framed as necessities to safeguard Tanzania's national sovereignty, but support definitely involved sacrifices, as Nyerere was quick to admit. Already in 1960, as prime minister, he had initiated the boycott of South African goods, telling his compatriots that “you have to be willing to pay the price”.Footnote 34 With this, Paul Bjerk has argued, he sought to “mobilize moral indignation through participation” and “plan[t] a seed for legitimizing future sacrifices”.Footnote 35

Yet, for some ordinary Tanzanians, independence was an achievement whose hard-won gains should be preserved in a primarily national framework. For them, sacrifice-inducing policy decisions and expressions of solidarity jeopardized newly won national sovereignty and prospects of improving living conditions. In a debate on ending the boycott of South African goods in 1962, for instance, Dar es Salaam's newest pan-African journal Spearhead published the opinion of the Tanzanian John O.Y. Malugaja,Footnote 36 who argued that cutting off trade relations with the apartheid regime amounted to “economic suicide”.Footnote 37 Responding in the next issue of Spearhead, the Dar es Salaam-based ANC representative Tennyson Makiwane said he was appalled by the “disgusting things” Malugaja had written and put his hope in “the overwhelming majority of the people of Tanganyika to reject this gentleman's call for the ending of the boycott against South Africa's racist-fascists”.Footnote 38 ANC representatives thus actively entered the battle over national public opinion and Tanzanians’ commitment to struggles elsewhere in the media. For that purpose, they also took to the streets.

Taking to the Streets: Political Rallies and Anti-Colonial Counter-Holidays

Political rallies helped liberation movements to create a public image as active and legitimate. This was an established technique of mobilization in East Africa, which Tanzanian politicians often used to drum up support and project political authority, both before and after independence.Footnote 39 Liberation movements also often initiated political rallies, subject to the permission of Tanzanian authorities. In the early and mid-1960s, cooperation among organizations projected influence, unity, and geographical reach, even as some of the movements tried to discredit one another. In 1962, for instance, a functionary of the Mozambican African National Union (MANU, later becoming a part of FRELIMO) invited leading representatives of Tanzania's TANU, Mozambique's UDENAMO, Zambia's UNIP, South Africa's ANC and PAC, Zimbabwe's ZAPU, Namibia's SWANU and SWAPO, as well as the transnational PAFMECA to join the march and appoint speakers.Footnote 40 Displaying strength in numbers was a key objective of cooperation. In April 1964, FRELIMO's vice president, Uria Simango, promised to mobilize “thousands of members around DAR [es Salaam]” for an ANC rally protesting death sentences against operatives of Umkhonto we Sizwe, the ANC's armed wing, in South Africa.Footnote 41 Sympathetic media such as the Ghanaian Times announced “mammoth rall[ies]” jointly organised by TANU and “all nationalist organisations represented in Tanganyika”, yet according to Western observers, the local impact of such demonstrations was initially limited. The French embassy reported in 1964 that an ANC rally under TANU patronage during “South Africa Week”, for instance, saw fifty protesters passing “under the indifferent gaze of passers-by”; generally, marches and other propaganda activities of liberation movements “met with little response from the general public”.Footnote 42

Broader audiences were reached if these events were covered by national and international media; yet, even when they were not, marchers could at least address crowds and passers-by. Placards thus often featured slogans written in both English and Kiswahili. In the capital Dar es Salaam, political rallies and charity events were staged in large venues (e.g. Arnautoglu Hall), on main streets, and in central squares such as Mnazi Mmoja, where the TANU headquarters were located. Tanzanian authorities were continually involved by granting permission, co-organizing, or even mobilizing crowds. The OAU's African Liberation Committee, with a Tanzanian executive secretary and Tanzanian staff, as well as excellent links to authorities, helped in coordinating the calendar of national counter-holidays such as the ANC's “Liberation Day”, “Frelimo day” (Mozambique), or, celebrated since 1963, “Zimbabwe Day” (later renamed “Chimurenga Day”).Footnote 43

Gradually, a number of these events morphed into Tanzanian-led initiatives that sought to express and harden citizens’ anti-imperialist attitudes. By the late 1960s, the calendar was busy as TANU, the TANU Youth League, and autonomous student groups organized celebrations of counter-holidays established by liberation movements.Footnote 44 During those years, the university campus, located some miles away from the city centre, emerged as a point of direct contact between liberation movements and the university's students and staff. Leading representatives, such as Amílcar Cabral, Eduardo Mondlane, and Agostinho Neto, gave lectures on campus, alongside other radicals, such as the African American political activist Stokely Carmichael (later Kwame Ture).Footnote 45 Students and faculty organized lectures, study groups and teach-ins, public rallies and study trips, often in cooperation with the TANU Youth League and TANU, as well as liberation movements.Footnote 46 In 1970, for instance, ANC functionaries were invited to speak at a rally organized by the TANU Youth League's university branch to protest Western countries’ weapons sales to South Africa.Footnote 47

While rallies organized by liberation movements generally seem to have been orderly and well disciplined – unsurprising given that these organizations depended on the patronage of the host government – protests by Tanzanian youth sometimes provoked reactions by authorities as they occasionally jeopardized the country's diplomatic respectability. In a protest against Britain's feeble reaction to Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence in 1965 (which effectively enshrined white minority rule in the country), for instance, university students not only called upon the British government to intervene militarily in several letters, but they also staged an unauthorized demonstration in the city centre, burned the British flag, set fire to the British High Commissioner's car, and broke windows in the environs of the High Commission. While Nyerere shared the students’ anger over the British failure to act – in fact, the government broke off direct bilateral relations in the wake of the Rhodesia event – he did not approve of their methods and made them apologize to the High Commission.Footnote 48 When one of the students, named Mwabulambo, objected, Nyerere ordered him to be caned.Footnote 49 In a later conversation with Nyerere, Mwabulambo explained his action in a language of anti-imperialist citizenship: “I don't regret. It was the patriotic duty of students of Tanzania, and you know it.”Footnote 50 In fulfilling the very principles that the government itself proclaimed, radical expressions of transnational solidarity thus trumped obedience to national authorities. Such forms of Tanzanian student politics, as Saida Yahya-Othman has argued, were unlike 1960s student radicalism elsewhere: they were neither clearly anti-state nor fully supported by the state.Footnote 51 Students often embraced principles proclaimed by the government but employed means of protest unavailable in the sphere of foreign diplomacy.

This became evident in protests in July and September 1968. On 20 July 1968, a group of roughly 100 to 150 mostly male university students and further members of the TANU Youth League condemned the US offensive in Vietnam. An image of the protests (see Figure 2) shows that a car of the ruling party TANU was also present. Anti-imperialist messages in support of Ho Chi Minh and the Vietnamese people were interspersed with unapologetically anti-capitalist slogans such as Ubepari ni mavi (Capitalism is shit). It was the first student protest permitted by the ruling party since October 1966, when university students had protested against the obligation to enrol in the National Service (discussed below) with elitist arguments.Footnote 52 As Roberts has shown with reference to this and other declarations of anti-imperialist solidarity that marked “Tanzania's 1968”, the line between the one-party state and “civil society” was blurred, to say the least.Footnote 53 The protest in front of the US embassy was led by the chairman of the university branch of the TANU Youth League, Juma Mwapachu. Just one month later, Mwapachu led a group of 2,000 youths who stormed the Soviet embassy to protest the invasion of Czechoslovakia. The protests were in line with the official position of non-alignment and anti-imperialism; indeed, the government had also criticized the Soviet invasion by claiming to “oppose colonialism of all kinds, whether old or new, in Africa, in Europe, or elsewhere”.Footnote 54 The overlap between official and popular protest was no coincidence. Unknown to contemporary observers, Mwapachu had received a call from Nyerere to organize this demonstration, in an effort to criticize the USSR through public protest rather than diplomatic channels.

Figure 2. Protest against US aggression in Vietnam, in front of the US embassy, Dar es Salaam, 31 July 1968.

Source: University Archive Leipzig, UZ 146. Photographer unknown.

Attacks against both the US and the USSR showed that Tanzanian anti-imperialism was tied not to taking sides in superpower politics but to the recognition of national sovereignty and self-determination. This meant that the imagined communitas of anti-imperialist citizenship could occasionally even include European states such as Czechoslovakia. Anti-imperial sentiment rather than socialist internationalism (further discredited by Soviet actions) was at the heart of these protests. Circles of affinity included Vietnam, but also Maoist China, with which Tanzania entertained increasingly close relations after the provision of military aid in 1964. As Lal has shown, “shared imaginaries” with China were based on a joint emphasis on self-reliance and rural development, but also anti-imperialism. Nyerere lauded China in 1965 and 1967 for pursuing a revolution “with anti-imperialism at its core” and for being “the only developing country which can challenge imperialism on equal terms”.Footnote 55 In some demographics, particularly among young male activists, these discourses of unity with the Vietnamese or Chinese against Western imperialism reverberated, making them part of a broader communitas that affirmed postcolonial national sovereignty as well as “their commitment to anti-colonial world-making”.Footnote 56 The state also established new channels through which to instil this commitment among young people.

Instilling Frontline Citizenship in the National Service

A key institution for forging a subjectivity of frontline citizenship commensurate with authorities’ requirements was the paramilitary Jeshi la Kujenga Taifa (JKT – literally “Nation-Building Army”), or National Service, established in 1964. Modelled on the Ghanaian Builder Brigades and inspired by Israeli advisers as well as other youth services in the Cold War world, such as the US Peace Corps, the National Service meant to direct the labour and energy of youths into channels controlled by the one-party state. From 1966 onwards, secondary school leavers and graduates of institutions of higher learning were obliged to serve in the National Service for several months, which made it, in the words of Bjerk, “a modern rite of passage […] designed to socialize youth into the nationalist vision of the TANU government”.Footnote 57 This nationalist vision entailed components reaching beyond the nation itself. Some National Service contingents were deployed to the Mozambican border, where the JKT helped to militarize the region in support of FRELIMO's ongoing war, begun in 1964, against the Portuguese.Footnote 58 Training in the National Service included lectures and other modes of instruction to turn Tanzanian youths into anti-imperialist citizens. Not everybody was convinced that this was working. A report by a TANU Youth League functionary, submitted to Vice President Rashidi Kawawa, agreed that the National Service should “produc[e] disciplined […] good and reliable citizens” through various means, including political education. However, the Israeli advisers assisting in establishing the National Service were reluctant to allow political education, and the quality of political instruction through Tanzanian officers, according to the report, was low. The result was that young men (women were not mentioned in the report, although they were present in the National Service and in public displays – see Figure 3) were “being trained to handle arms but not knowing what exactly to defend, besides slogans directed against ‘Mreno’, ‘Smith’ or ‘Kabulu’”, that is, the Portuguese, the prime minister of Rhodesia, and the Boers.Footnote 59

Figure 3. Tanzania's paramilitary National Service represented on a stamp, 1967.

Source: MoO/016/135/21, University of Fort Hare, ANC Archives.

Precisely such slogans are extremely prominent, however, in memories of graduates of the National Service. Mathematician and radical activist Karim Hirji, for instance, emphasized the catalysing role of songs during his National Service stint in 1968. Already at secondary school, topics of anti-imperialism and liberation movements “were a constant presence in our lives”, which “rubbed off and affected our consciousness”. At the Kinondoni National Service Camp, this exposure was intensified through lectures and “songs we sang during drills and jogs”, songs that “roundly denounced colonial and racist leaders and views”.Footnote 60 The denounced leaders also included apartheid's African ally Kamuzu Banda, the “neo-colonial” president of neighbouring Malawi.Footnote 61 Some of the songs, also sung in the TANU Youth League and secondary schools, were very explicit as far as bloodshed was concerned. A popular tune included the call “If a Boer comes” (Kaburu akij[a]), followed by the response “slaughter him!” (chinja!). Another song had marchers sing “Slaughter, slaughter, slaughter the Portuguese” (Chinja, chinja, chinja Mreno).Footnote 62 The journalist Godfrey Mwakikagile similarly recalled his 1971–1973 stint in the National Service as a formative time that “helped instill in us not only egalitarian values but a strong sense of patriotism” through lectures and “pretty violent songs, ready to irrigate our land with the blood of the enemy, reminding ourselves that we were on the frontline of the African liberation struggle”.Footnote 63 Retrospectively, Hirji, mentioned above, saw this as problematic: while he considered armed struggle as a legitimate form of anti-colonial resistance, this only applied to certain contexts. To him, the way Tanzanians were encouraged to kill enemies, both internal and external, “implied denial of the common humanity of all on this planet”.Footnote 64

As the National Service was a training ground for civil servants and state employees, lessons imparted in the camps resonated in other sectors of society. Some “graduates” of the National Service continued to wear its uniforms at university, as a sign of their commitment. Political education imparted during the National Service produced a cohort of so-called political commissars who delivered lectures on the necessity of vigilance and anti-colonial solidarity.Footnote 65 These political commissars were sometimes still young university students who then lectured new recruits of the National Service, but also rural communities that had to host groups of exiles in refugee camps, members of the armed forces, and even civil servants.Footnote 66 The younger generation had to educate more senior citizens. The publisher Walter Bgoya, who worked at the Foreign Ministry between 1965 and 1972,Footnote 67 recalled that “it was still essential for the Party cadres to organize ideological classes in order to mobilize and win the support of members of the civil servants, many of whom believed that the Government was wasting time and resources by supporting the liberation struggles in southern Africa”.Footnote 68 Bureaucrats, many of whom were still trained under the British, thought in terms of Tanzanian national self-interest and the possible costs and risks that came with the support of liberation movements. According to Bgoya, sceptics “slowed things down, frustrated the more radical supporters of the liberation movements, and even occasionally resorted to calling them CIA agents as a way to discredit them”.Footnote 69 Yet, even if some Tanzanians questioned the official stand on solidarity and only paid “lip service to liberation”,Footnote 70 there was no open dissent against the policy of non-aligned anti-imperialism. The National Service contributed to the hegemony of this outlook.

Mouthpieces of the One-Party State: Making Anti-Imperialist Media

Mass media and popular culture had the capacity to reach even broader segments of the population. The most important medium was radio, with around 1.8 million radio sets in use in 1973.Footnote 71 Broadcasts were not limited to speeches by Tanzanian politicians on the importance of supporting the anti-imperialist cause. Liberation movements received airtime on Radio Tanzania Dar es Salaam (RTD)'s external broadcasting services – at its peak, their programmes made up seventeen per cent of RTD's programming – to send messages primarily intended for audiences “at home” in English, French, and various vernaculars. These broadcasts were also listened to in Tanzania. While the language barrier frequently “prevented Tanzanians from understanding the political content that the ANC and other liberation movements produced, they nevertheless noticed the presence of these broadcasts and heard the songs”.Footnote 72 In the 1970s, many bands in Tanzania's lively music scene also composed songs with Kiswahili lyrics calling for solidarity with liberation movements, for example “Zimbabwe iwe huru” (“Zimbabwe should be free”), “Tuikomboe Afrika” (“Let us liberate Africa”), or “Viva Frelimo” by NUTA Jazz Band, or “Masikitiko” (“Laments”) by Marijani Rajabu and Dar International. Some parts of the solidarity discourse thus “thrived outside state patronage” but could still be influenced by and supportive of official discourses, as Suriano has argued.Footnote 73 This was also true of print publications in English and Kiswahili, although the messages here were often more ambivalent.

Government- or party-owned newspapers championed the cause of liberation and anchored a geography of ongoing struggles in the minds of urban literate audiences. This was a process, however, and newspapers – including the party-controlled ones – were generally supportive of the generic cause of “African liberation” but potentially critical of particular liberation movements. In the early 1960s, in a media landscape still dominated by privately owned newspapers and tabloids, coverage of anti-colonial struggles increased. In July 1961, Zambian UNIP functionary Sikota Wina complained about the “parochialism” of the East African press that did not provide information about his country.Footnote 74 In 1962, however, major newspapers such as the independent, but (since 1957) clearly pro-TANU, Catholic biweekly Kiongozi ran title pages on Zimbabwe's ZAPU opening an office in Dar es Salaam and the dissolution of the Central African Federation.Footnote 75 The Catholic Kiongozi, in which reporting on liberation struggles was sometimes tempered by religious conservatism and a strong current of anti-communism,Footnote 76 defended anti-imperialist events, such as the 1963 Afro-Asian Solidarity Conference in Moshi, against red-baiting claims that the Afro-Asian Peoples’ Solidarity Organization (AAPSO) was but a communist front organization.Footnote 77

News relating to the presence of liberation movements within the country did not necessarily paint a positive image, however. When a group of Mozambican exiles attacked FRELIMO functionary Leo Milas in 1963, the Nairobi-based commercial tabloid Daily Nation reported on a “Frelimo brawl” caused by an “angry mob of refugees” attacking Milas,Footnote 78 who was, as the article also pointed out, suspected of being an “American spy”.Footnote 79 Such reports established durable tropes of the double threat of destabilization from both undeserving “refugee” populations and subversive colonial or Cold War agents disguised as liberation fighters. Aiming to increase control over news and narratives circulating in the public sphere, the ruling party established its own newspaper in an English and Kiswahili edition, The Nationalist and Uhuru, in 1964. Nyerere handpicked its first editor, the Radio Ghana official James Markham.Footnote 80 Markham was a fiery anti-imperialist with ample experience in Afro-Asian circuits and media production, but he quickly became an embarrassment to the government as he took to insulting Western diplomats during his frequent drinking binges in Dar es Salaam's bars.Footnote 81 In 1966, Nyerere replaced Markham with Benjamin W. Mkapa, a young Tanzanian politician who had only modest prior experience in editing but was a loyalist who seldom overstepped the (sometimes invisible) boundaries of what could be said in the Tanzanian one-party regime.

Under Mkapa's watch, journalists cultivated close relations with liberation movements, regularly reported about their activities, and mentioned anti-colonial support as a linchpin of TANU's policies.Footnote 82 In the foreword to Mkapa's autobiography, Mozambican president Joaquim Chissano recalls that his party FRELIMO always enjoyed “the full support of these party newspapers”, The Nationalist and Uhuru, which “were in the forefront of mobilising the people to support us in every way possible”.Footnote 83 Contemporary memory politics have erased any tensions, but there were plenty. Many Mozambican refugees were ethnic Makonde, a group that lived on both sides of the border, and several Tanzanian politicians and journalists, including radicals in the TANU Youth League, shared affinities with Mondlane's opponents. As George Roberts has shown, prior to the assassination of FRELIMO's leader Eduardo Mondlane in 1969, the local press had published a number of hostile reports, which “helped to establish a discursive environment which facilitated challenges to Mondlane's authority” – including an article in the party-owned Nationalist, which claimed that the CIA had penetrated FRELIMO.Footnote 84

Criticism of particular liberation movements, factions, or leaders was by no means equal to a critique of anti-colonialism and solidarity as such – quite to the contrary: the state-controlled newspapers and radio “vigorously supported and unvaryingly applauded Nyerere's Southern African policy”, as Arrigo Pallotti has argued.Footnote 85 Yet, Tanzanians used media to communicate their expectations to liberation movements without shying away from rhetoric that estranged the audience from particular organizations and sparked more general resentment of both exile politics and its Tanzanian support. The ANC's Ben Turok, who spent three years in Tanzania (1965–1968) and served in a leading position in the Ministry of Lands, recalled that “the government was obviously anxious about the presence of so many revolutionaries”, referring to them “sometimes as ‘Wakimbizi’ (refugees, or more literally, runaways)” who were subjected “to derogatory comments in the official press and even by Tanu leaders”.Footnote 86 At one point, in the late 1960s, the ANC withdrew from a student symposium on liberation movements due to an attack in the Daily Nation, which portrayed liberation movements as “cowardly and content to enjoy the fruits of exile”, a line of critique that was gaining currency from the mid-1960s onwards.Footnote 87

In another effort to establish a closer rapport with the population and the authorities, the ANC produced the short-lived bulletin Nyota ya Uluguru (“Star of Uluguru”, see Figure 4). The bulletin's name referred to the mountainous area of Uluguru with its main town, Morogoro, where the ANC had moved its headquarters in early 1965 following the Tanzanian government's directive to restrict the size of liberation movements’ offices in the capital Dar es Salaam to four persons. In contrast to other ANC publications, which addressed South African or broader international audiences, the three issues of this bulletin primarily targeted Tanzanians. The bulletin merged the topic of liberation in Southern Africa with quotes from Tanzanian politicians calling for liberation in the country through the support of Ujamaa and “self-reliance”, the Tanzanian socialist project that the ruling party had firmly anchored in its February 1967 Arusha Declaration. While Nyota ya Uluguru was published by the ANC (“Inatolewa na African National Congress”), numerous Tanzanian bureaucrats and regional politicians as well as trade unionists had assisted in its making. The contents of Nyota ya Uluguru straddled the line between calls for internationalist solidarity with the ANC and liberation struggles at large, on the one hand, and TANU propaganda for the country's socialist project, on the other.

Figure 4. Front page of the first issue of Nyota ya Uluguru, published by the ANC in Morogoro. Source: MoO/016/125/1, UFH, ANC Archives.

The publication's emphasis on shared goals did not help, however, to fend off increasing tensions between the Tanzanian government and liberation movements in the late 1960s over security concerns. In June 1968, Tanzanian police confiscated documents from the ANC headquarters in Morogoro. The ANC functionary Mzwai Piliso reported that this intervention “put us in a very embarrassing position and damaged further our image in the eyes of the public in Morogoro”.Footnote 88 The events unfolded into a worst-case scenario for the ANC as the government ordered the evacuation of all its military cadres from Tanzania in 1969. As no other African country offered camp space, the entire armed wing was airlifted to the Soviet Union. The temporary expulsion – the recruits were later allowed to return – was likely related to a coup attempt against Nyerere, which the ANC leadership had been informed of, but which they had failed to warn Tanzanian authorities about.Footnote 89 Against lingering suspicions of betrayal, the ANC leadership once more felt the need to actively cultivate support not only among the Tanzanian elite, but also in Tanzanian society.Footnote 90

At the time, media discourse in the country became increasingly partisan. While there was no full-blown censorship, pressure on media outlets to conform with the doxa of the one-party state increased. As in the case of protests against superpower interventions discussed above, youth activists sometimes communicated the messages in a more radical fashion than the government. In 1969, hundreds of Tanzanians, led by the so-called Green Guard (a reference to the Maoist “Red Guard”) of the TANU Youth League, demonstrated against the “imperialist” editorial policies of the commercial newspaper The Standard.Footnote 91 In the same year, The Standard was nationalized. Under the editorship of the South African Frene Ginwala, who had edited the aforementioned Pan-African magazine Spearhead between 1961 and 1963, The Standard ran reports in anti-colonial registers from China's Xinhua and the Soviet news agency TASS, and it replaced terms such as “terrorists” with “freedom fighters” in contributions taken from Western agencies.Footnote 92 The Standard was unapologetically partisan, but it also remained critical vis-à-vis the government – albeit only for a short period.

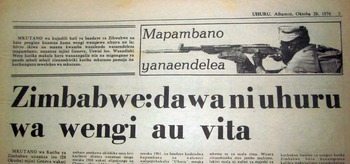

When Ginwala was ousted in 1971 (after an op-ed that undermined the government's diplomatic rapprochement with Sudan), Nyerere instructed Mkapa, who had previously edited the party newspapers The Nationalist and Uhuru, to take over. In an interview, Mkapa remembered the “extremely aggressive advocacy” (Advocacy kalikali kabisa) for liberation under his watch.Footnote 93 Uhuru was “mostly read by the low income earners and less educated section of the population”, which made it the largest-selling paper during the one-party era with a circulation of roughly 100,000.Footnote 94 The masculinist image of the archetypical guerrilla fighter (see Figure 5), a Weberian ideal type, reflected the broader shift towards armed struggle and the expectation that liberation movements engaged in military action. In the 1970s, regular reporting and sections such as “The Struggle Continues” (Mapambano yanaendela) kept Zimbabwe, South Africa, and Namibia alive in the minds of Uhuru's readers. Readers themselves voiced their moral support in various ways. In the poems sections of many newspapers, a traditionally vibrant locus of political debate in Tanzanian print culture, citizens contributed works that affirmed their support for African liberation, condemned racist regimes, and praised the leaders of liberation movements. The topic of liberation also entered popular prose beyond media controlled by the one-party state. Elvis Musiba's popular series of pulp fiction novels, issued by a briefcase publisher, invited Kiswahili-speaking readers – especially young urban men – to identify with the James-Bond-esque Willy Gamba, a Pan-African secret agent of Tanzanian origin who brought down Portuguese spies together with FRELIMO forces and tracked down assassins of South African freedom fighters.Footnote 95

Figure 5. Communicating liberation struggles via heroizing iconographies: “The Struggle Continues” section in the party daily Uhuru, 26 October 1976.

Material Solidarity: Shillings, Bullets, and Blood

These imagined affinities evolved in parallel with material practices through which citizens could claim to make their own direct contribution to liberation struggles. In Tanzania, acts of giving and sacrifice in the name of anti-colonial solidarity were rarely bureaucratized or translated into regular rituals of material transfer. Instead, citizens were often mobilized on an ad hoc basis, with initiatives sometimes originating from the higher echelons of power, sometimes in local branches of the party, women's organization, trade unions, or youth leagues, and sometimes from social spaces that were not directly linked to institutions of the one-party state. These practices were often characterized by explicit or implicit links between Tanzanian citizenship and liberation struggles, portraying solidarity as a patriotic task. With limited material resources, both the government and the population could not be expected to be the liberation movements’ main providers of financial assistance. Still, the Tanzanian government – in contrast to most other African member states – regularly transferred the due amounts to the OAU's Liberation Committee and also channelled resources bilaterally to liberation movements.Footnote 96

In addition to their contributions as taxpayers, Tanzanians made donations individually or as groups, though often through channels of the one-party state, including its mass organizations. During political rallies and events such as Africa Day, funds were collected on the spot.Footnote 97 Following the announcement of the 1971 TANU Guidelines, which sharpened the ruling party's African liberation profile, a fundraising committee was established that collected donations from the general public – in addition to the government's regular contributions to the OAU's liberation committee.Footnote 98 The extent of contributions is unknown, but it is clear that several liberation movements received substantial payments in the 1970s from this source.Footnote 99 The conceptual difference between freedom fighters and refugees served to distinguish apolitical humanitarian aid from anti-imperialist solidarity in line with frontline citizenship. The Catholic Kiongozi, for instance, reported on the help of UN institutions for “refugees” (wakimbizi) from Mozambique, Burundi, and Rwanda but mentioned donations from regular Tanzanians and Catholic priests for the Mozambican “liberation struggle” (harakati za ukombozi).Footnote 100 To some extent, the material support practices were gendered. Branches of the official women's organization Umoja wa Wanawake wa Tanzania (UWT) held dancing events to raise funds and collected money during annual meetings.Footnote 101 According to the former Secretary General of UWT, Mama Lea Lupembe, most members had little income but still followed the ethos “if we are citizens, we have to take part”.Footnote 102 Collected sums were more substantial, Lupembe recalled, when UWT members from the Tanzanian-Asian community engaged in fundraising. In any case, fundraising was “not programmed” and “done for refugee women (wanawake wenzetu wakimbizi), not freedom fighters (wapigania uhuru)”.Footnote 103 This chimed with the UWT's conservative focus on welfare, development, and matters of everyday survival, often assigned to women.Footnote 104 But the politics of liberation struggles were by no means absent, nor were exiles. ANC women were invited to participate in the organization. Edith Madenge, one of the South African nurses who had arrived in 1961, even became a member of the UWT's Central Committee, represented the organization in international conferences, and infused the ANC's concerns and calls for material solidarity in UWT meetings.Footnote 105

In line with sentiments shaped by the growing emphasis on armed struggle, other groups wanted to see their support as contributions to military efforts. This was true of the TANU Youth League, which was theoretically open to all genders but, in practice, often excluded or sidelined women. In June 1968, Gwaponile Akim Mwanjabala, the chairman of the TANU Youth League branch at Mkwawa High School in Iringa, central Tanzania, sent a donation of 300 Tanzanian shillings to the ALC (with the letter copied to party headquarters) in the name of all TANU Youth League members at the school. Mwanjabala clarified that this small amount was to be earmarked “to buy even two guns so that the freedom fighters in Rhodesia and Mozambique may succeed in terminating this colonialism and savagery there”. The letter ended with the statement that “we have been mistreated [kuonewa] long enough, so now we want a revolution […] and in the end we shall look for the GUN”.Footnote 106 Like other donations made at the time, it was probably linked to a call by the ALC's executive secretary, the Tanzanian George Magombe, about two months earlier, to “buy a bullet for the heroes” fighting colonialism in Southern Africa. Media reports showed Magombe receiving a cheque for 140 Tanzanian shillings from the chairman of the radical University Students’ African Revolutionary Front (and later president of Uganda) Yoweri Museveni.Footnote 107

Tanzanians also supported liberation struggles in more direct and physical ways. Following the beginning of FRELIMO's armed struggle in 1964, Tanzanians queued in front of hospitals, heeding the call to donate blood for injured Mozambican liberation fighters.Footnote 108 Some even showed readiness to sacrifice their lives. In February 1973, Y. Yamboboto, the executive secretary of the local TANU branch of Mpanda (a small peripheral town in Tabora district in the west of Tanzania), informed the party's national headquarters by letter that eleven men living in Mpanda were “ready to go and help in the Liberation Struggle in Quine Bisau [Guinea-Bissau]” against Portugal.Footnote 109 The list provided in the letter showed that these men were aged between twenty and twenty-four years. Eight were employees or civil servants of state institutions at the regional level (including the departments of home affairs, education, agriculture, and resources), and three were listed as peasants (wakulima). The letter linked citizenship and liberation struggles by pointing out explicitly that all of them were of Tanzanian nationality. West African Guinea-Bissau may have been far away in geographical terms – almost 6,000 kilometers – but in terms of imagined geographies of solidarity, it was very close. Portugal was a common enemy that had also killed Tanzanians in 1971 and dropped napalm bombs along the border with Mozambique in 1972.Footnote 110 The letter from the TANU branch in Mpanda was probably a reaction to the assassination of Amílcar Cabral in January 1973, which had stirred anti-colonial sentiments across the globe and sparked protests in Tanzania.Footnote 111 It remains unclear if they received a response, but it is significant that these men did not just leave on their own accord. They sent a letter to the party headquarters and embraced the link between patriotism, party authority, and militant transnational anti-colonialism that involved the readiness to sacrifice one's life.

Like this group of young state employees and peasants from Tabora, university students also tried to get involved in liberation in more direct ways than protests or fundraising. Some did so by visiting the “liberated zones” across the border in northern Mozambique. In one report, published in a FRELIMO periodical issued in Dar es Salaam, they enthusiastically wrote about “why they went, what they saw”. Their report pointed to exclusionary and contradictory dimensions of frontline citizenship, reflecting contempt for South Asians in Tanzanian society: “In one particular aspect, we believe that the Mozambican is freer than any citizen in the East African countries. For there is no Asian trader – the indispensable middle-man! FRELIMO is the sole buyer and seller.”Footnote 112 Sentiments of solidarity thus also rested on racialized understandings at the heart of popular understandings of citizenship that were far from the lofty ideals of Afro-Asian unity or horizontal kinship ties invoked in discourses about the Vietnamese or Chinese. As Brennan has pointed out, the very term mwananchi (“citizen”, literally child of the land) usually referred to black Africans, while its popular antonym “Patel” referred to citizens of Asian origin and evoked undertones of anti-socialist, exploitative economic practices, and permanent foreignness.Footnote 113 While Chinese and Vietnamese were imagined as kin (“brothers”) in the fight against imperialism, “Indians” (wahindi) within the country were frequently seen as obstacles to anti-colonial nation-building and the attainment of economic sovereignty.

The support of struggles abroad thus sometimes sat uneasily with cleavages within the country. Nevertheless, elites felt that anti-colonial support could and should bolster Tanzania's project of building a socialist nation. In August 1973, Amon S. Nsekela, in his function as the chairman of the University Council, lauded the good record of the TANU Youth League and progressive students in supporting liberation movements but wanted to “[h]ammer home the point that the liberation struggles have a significance which goes well beyond their national or territorial boundaries”. To Nsekela, practices of anti-colonial solidarity were a means of harnessing the dynamics of these struggles for socialist nationalism. As he pointed out, the new generation of young Tanzanians, a significant part of the growing population, had no personal experiences of colonial oppression and anti-colonial struggle within Tanzania. They thus had to be involved in ongoing struggles elsewhere, as this would convince them to support the ongoing effort of building socialism in Tanzania.Footnote 114 This paralleled hopes of Eastern European elites that slackening enthusiasm for the building of socialism among the youth could be reinvigorated with anti-colonialism and the perception of “themselves as members of a transnational army of progress and revolution that was growing in strength”.Footnote 115 Yet, in Tanzania, it was socialism on a national scale, connected to transnational anti-colonialism, which most often appeared in a Pan-African register. Nsekela demanded compulsory courses on the “significance of revolutionary struggle in Africa” at all faculties and called on the university community to “mobilize donations for the OAU Liberation Fund”.Footnote 116 This further push for material contributions was also felt beyond the university but was not received without contestations.

Dissent and Decline: Divided Frontlines

By the late 1970s, the frontline citizenship discourse was fading. Tensions erupted already in the early years of the decade when the semantics of “liberation” were stretched and the one-party state's push for material and non-material contributions increased. In 1971, the party published a new set of guidelines (the Mwongozo), a radical document that called upon Tanzanians to reject exploitative practices both within and beyond the country. The Mwongozo was informed by events beyond the country's borders, most notably Idi Amin's coming to power in Uganda and a Portuguese invasion in Guinea-Conakry. The new guidelines ushered in a fuller militarization of Tanzanian society, making it a civic duty to undergo paramilitary training in people's militias to be prepared in the fight against both external and internal enemies.

Many workers carried a booklet with the text of the Mwongozo in their pocket but translated the register of anti-colonial liberation to their own ends. At the Tanzania Portland Cement Company, for instance, labourers likened their manager to “Smith of Rhodesia”. As workers framed their actions as forms of “liberation”, citing the Mwongozo, the number of strikes and other forms of industrial dispute surged to new heights between 1971 and 1975.Footnote 117 In 1975, Minister of Housing and Lands Thabita Siwale told workers to increase productivity and “fight the liberation struggle of work”. In her statement, she pre-emptively delegitimized demands for better working conditions and higher wages, saying that these always came from “sluggards”. Moreover, she called on the country's trade union National Union of Tanganyika Workers (NUTA) – effectively co-opted in 1964 – to fight all lazy persons and “big exploiters”, drawing on earlier party discourses in which laziness was framed as a form of exploitation.Footnote 118 The struggle between workers and elites jeopardized the unity necessary to support struggle along the frontline of transnational solidarity.

In 1972, workers opposed the decision of trade union authorities that they should contribute a small amount to the national liberation fund.Footnote 119 In letters to government-owned newspapers, readers argued that they were already “over-taxed” and said they were unwilling to contribute to the upkeep of “freedom fighters [who] continue to marry Europeans, sit behind very expensive mahogany desks, and drive the most expensive cars”.Footnote 120 This trope of illegitimate luxury was well established through previous articles in the government press, but the letters signalled “wider grassroots unease at the costly burden it placed upon ordinary citizens”.Footnote 121 Similar discontent at the financial burden of supporting liberation movements has been identified by Jeffrey Ahlman for the case of Ghana under Kwame Nkrumah.Footnote 122 Both political elites and citizens thus harnessed the language of anti-colonial liberation, albeit at times for opposing ends. This contributed to an overstretch and hollowing out of the language of liberation.

The impact of young radical leftists at university also waned as authorities banned organizations that operated outside state-sanctioned channels and replaced them with institutions under party control.Footnote 123 In the mid-1970s, TANU or its large youth wing organized large anti-imperialist protests, with 2,000 participants or more, against US policies or apartheid South Africa, with representatives of liberation movements speaking during those events.Footnote 124 The state's security organs were also mobilized and turned parades of liberation movements into displays of Tanzanian protection and solidarity. A 1972 FRELIMO procession was led by the Tanzanian police band, while, in the mid-1970s, Tanzanian soldiers marched alongside South Africans who had escaped after the 1976 Soweto Uprising, nurses of the armed forces condemned the pseudo-independence of Transkei in front of the TANU Youth League headquarters, and 1,600 army sportsmen and women finished their march in support of the African liberation struggle by handing a cheque for more than 500 Tanzanian shillings (334 pounds sterling) to Nyerere.Footnote 125

Although anti-imperialist references to a broader communitas by no means disappeared, the hegemonic rhetoric began to crumble. South Africans, whose number in Dar es Salaam and several camps in the country was growing again after the Soweto Uprising in 1976, were not only called refugees (wakimbizi), but also wasoweto, a shorthand for exiles who “gained a reputation of being drunkards and troublemakers”.Footnote 126 Tensions were rife and “resentment […] began to manifest itself more openly”, as Suriano has noted.Footnote 127 The state held on to its mission, however. Among the more recent arrivals was Kedy Rose Jolly, who had taken part in the 1976 Soweto Uprising and left apartheid South Africa at the age of sixteen. She recalled that Nyerere still “corrected the masses through the media”, telling them to refer to the South Africans as “freedom fighters”, and “the masses began to follow and perceive us as they were getting closer to us”.Footnote 128

In the late 1970s, the ailing economy and the war against Uganda's Idi Amin contributed to the shift of imagined frontlines. In some ways, the war rejuvenated Tanzanian nationalism, as many citizens volunteered to defend their country against the Ugandan invasion and drive Amin out of the country. Nyerere linked this discursively to the established tropes of frontline citizenship as he likened Amin to Rhodesia's Ian Smith and South Africa's John Vorster, pointing out that Amin had killed even more Africans than the latter two. Yet, the war did not neatly fit into Pan-African terms as the government had to fend off accusations that the counter-invasion and toppling of Amin violated the OAU's Charter and even constituted a form of colonialism.Footnote 129 Tanzania received hardly any assistance from other countries for the war effort, which deepened the economic crisis and forced people to think about next week's income rather than internationalist solidarity. Despite tensions, Tanzanian support continued throughout the 1980s, even when Nyerere stepped down as president in 1985 and made way for neo-liberal reforms. In the National Service and elsewhere, songs demanding unity to liberate all African countries and calling for the killing of enemies such as “the Boers” remained popular.Footnote 130 Sometimes, citizens, including peasants and workers, made donations and staged protests, even as the state tried to roll back solidarity and sought to dissipate spontaneous responses, always fearful that discourses of liberation could highlight contradictions within the country as measures of structural adjustment were implemented and heightened inequalities to unprecedented levels.Footnote 131

Conclusion

Links between Tanzanian citizenship and anti-imperialist liberation went back to regional cooperation to speed up decolonization in the late 1950s. From 1960 onwards, anti-colonial and anti-apartheid organizations were hosted in the country and engaged with Tanzanian decision-makers as well as citizens to foster a spirit of solidarity. In many practices, there was no clear separation between top-down and grassroots initiatives and “internal” or “external” actors; political rallies, publications, and fundraising events were often co-products of Tanzanians’ and liberation movements’ initiatives. The discourse of liberation also had the potential to accentuate tensions within society, which is why radical youth organizations, for instance, were banned and solidarity was increasingly tied to institutions of the one-party state. This monopolization through institutional set-ups and hegemonic narratives, which intensified in the late 1960s and early 1970s, would ensure that solidarity was practised in ways that were not only acceptable to the government, but that also harnessed anti-imperialist sentiments for the project of socialist nation-building by mobilizing a young generation of citizens who came of age after independence. A mere top-down logic thus fails to capture the complexity of the solidarity regime. It was not a monolithic bloc, but rather a contested discursive terrain connected to mechanisms of micro-mobilization that were gendered and differed across generational axes.

This article has suggested the term “frontline citizenship” to capture the evolving solidarity regime with its imagined affinities and material practices, nationalist and transnational formats of spatiality, and overlaps between the community of Tanzanians and a broader, transnational communitas. The imagined reach of this communitas derived less from proletarian internationalism and more from Pan-Africanist currents and Third Worldist anti-imperialism; consequently, it was flexible. Although its main point of spatial reference was the African continent, it could also extend to Europe, East Asia, and elsewhere. Domestically, practices of transnational anti-colonial solidarity served to legitimize the socialist ujamaa experiment and the increasingly authoritarian state – as was the case with state-sponsored internationalism and state socialism elsewhere.Footnote 132 Frontline citizenship came with new duties, such as vigilance, symbolic support, and material contributions. Sacrifices were coded as evidence of moral superiority; yet, beyond a progressive self-understanding as being part of a communitas on the path to victory, these new duties did not come with new rights. While many citizens embraced the general cause of liberation, the term itself – like other key terms in the vocabulary of Tanzanian socialism – could be appropriated for different ends.Footnote 133 Authorities tried to delegitimize citizens’ claims made for liberation in other registers on the domestic front. Despite this instrumentalization, the transnational ethos of solidarity, which Tanzanians came to embrace through concrete encounters with liberation movements, media discourses, and institutions such as the National Service, continued to inform attitudes well beyond the end of Tanzania's experiment of building African socialism, particularly among the generation that came of age in the 1960s and 1970s and who filled the ranks of the expanding state bureaucracy. Anti-imperial world-making was thus more than an elite project – it has been enabled and enacted, but also contested, kept alive, and remembered by ordinary citizens.