You, Polish peasant and worker! If you wish to take your proper place in the family of free nations, if you wish to be the master of your own land, then you must take hold of power in Poland. Footnote 1

These words opened the manifesto issued by the government headed by the socialist politician Ignacy Daszyński, one of many power centres attempting to seize the reins of power in Poland in 1918. It was a short-lived government but nevertheless made an impact on the hopes and imaginations of the Polish people. Its promise was intended to ensure they continued to demand reform, while also keeping them loyal to the nation state. It proved successful to a degree, and the state survived, not something that could be taken for granted at a time when revolutionary shockwaves reverberated throughout Europe. Mocked by some of its enemies as a bastard of the Treaty of Versailles, Poland was nevertheless the largest new state, many of whose inhabitants could hope to “take their proper place”, just as the manifesto promised, setting the stage for the ongoing debate on the shape of the new Polish polity. One of the main forums of this debate was the newly elected parliament responsible for codifying the legal order of the new state and for preparing the constitution. In this context, I explore how the parliamentary debate responded to an internal labour militancy and external threat of war with the Soviet Bolsheviks.

In order to tackle this question, I build a theoretical framework of statecrafting in conditions of labour militancy and war. Subsequently, I develop a mixed approach to diet transcripts, combining distant reading and close hermeneutics of the texts. I then introduce the Polish context and show why this state-in-the-making is relevant for a broader debate on factors of democratization. Next, I analyse the parliamentary speeches, forming a sequence interwoven with historical events outside the chamber. In the first empirical section, I explore the period of internal labour unrest; in the second, I explore times of war waged against external enemies. Subsequent years saw post-war stabilization and the corresponding retrenchment of parliamentary voices. The insights into these three consecutive phases and the overarching sequence allow me to relate the findings on parliamentary rhetoric to the broader puzzles within the historical sociology of democratization.

INTERNAL LABOUR UNREST AND EXTERNAL WAR AS FACTORS IN PARLIAMENTARY DEMOCRATIZATION

Various social groups struggled to “find a place” in the changing social order of modernizing societies at the end of World War I. The growing urban working class had to be politically accommodated and integrated into state structures. Political systems were democratized step by step through suffrage reform, the introduction of welfare provisions, and redistributive corrections to the rise of industrial capitalism, “moving toward broader, more equal, more protected, and more binding consultation”Footnote 2 and embracing the essential equality of citizens within a political community.Footnote 3 This process – especially at the political level – accelerated after World War I, when existing states reformed their electoral systems and new ones rivalled them, introducing outspokenly democratic establishments. Students of democratization inquire about the factors determining its occurrence, pace, durability, and outcomes, but agree that the working class and the “social question” were central to this transformation. Labour militancy and war are two factors featuring prominently in this debate; they were hotly disputed in the Polish parliament, and certainly impacted the parliamentary rhetoric.

Regarding internal factors, the classical approaches in historical sociology presented capitalist modernization and the development of a liberal commercial elite as a precondition for democracy.Footnote 4 Some scholars have argued that what was actually decisive for democratization was the early institutionalization, structural embedding, and relative strength of conservative parties that accepted electoral politics.Footnote 5 Others, however, have stressed the democratizing pressure from below. It was the labour movement, usually mediated through socialist parties, which pushed forward measures aimed at political and social democratization. This was done either directly – after the socialists had attracted sufficient electoral support – or indirectly – when their growing power pressured the ruling elite to push changes forward out of fear.Footnote 6

Similarly, the external impact of war is ambiguous. There is a long tradition linking wars to labour militancy or to social conflict more generally. The “presumed nexus of civil conflict and international conflict” is considered “one of the most venerable hypotheses in the social science literature”.Footnote 7 However, the question remains what form this nexus and its temporal and causal dimension took. War might be a factor increasing social cohesion and weakening the potential of class politics. Correspondingly, it is often used to intensify patriotic sentiments, sidelining the demands of the popular classes in the name of national unity and the war effort.Footnote 8 But war is considered a vehicle for social inclusion, too. The war effort required the participation of the popular classes, which added legitimacy to calls for their incorporation into the political systems and for extensive welfare transfers.Footnote 9 Most European countries introduced universal suffrage just after World War I, and the European welfare states were built after World War II.Footnote 10 However, an alternative depiction suggests that war is a factor stimulating social conflict at the national level. It incites revolutionary turmoil through the extraction of resources and makes it more likely by weakening the repressive capacities of the state.Footnote 11 Curiously, the case discussed here contains elements of all these subvariants. Hence, they seem not to be mutually exclusive alternatives but complementary hypotheses of “different temporal relevance”.Footnote 12 That is, a revolutionary situation resulted from the dislocation caused by World War I, but nonetheless it might have been offset by another war perceived as a threat to the entire, newly unified national group.Footnote 13 Perpetuated by patriotic sentiments, the war could sideline the internal conflict. In addition, the experience of war could have been used by various actors and for divergent purposes in the ongoing debate on state democratization. Hence, the sequential variance applies too to the impact of war on the inclusion of new groups into the polity.

While Polish parliamentary democracy did indeed emerge after World War I, it faced a series of border conflicts and a fully fledged war with Bolshevik Russia, further complicating the situation. Despite being embedded in broader sequences of conflict on both sides, class conflict within Poland played less of a role than in other parallel wars on the fringes of the waning Russian Empire. For instance, Russian Bolshevik involvement in the civil war in Finland in 1918 was insignificant, though for ideological purposes highly exaggerated by the opponents of revolution. Instead, the conflict was played out between ideologically divided Finnish nationals.Footnote 14 Latvia was an intermediary case, and the conflict there was highly entangled, with local Bolsheviks running their own successful show before retreating with support from their Russian comrades.Footnote 15 In contrast, in the Polish case, the internal unrest and the war were a sequence of events occurring in quick succession. Despite Bolshevik attempts to kick-start a proxy communist regime headed by a seasoned Polish socialist like Feliks Dzierżyński [Dzerzhinsky], they largely failed to transform the war into an internal conflict on a mass scale.Footnote 16 Nonetheless, it was not only a war between states; it was also a clash between manifestly different visions of the social order. In this sense it was an international war, also having features of a class conflict.Footnote 17 Hence, in my view, the term “international class war” describes quite accurately the leading goals of both sides in the conflict, and renders possible the analytical angle proposed in this article.

Despite there being a clear sequence, in the Polish case the internal and external factors were entangled as the war was waged against a political project nominally fostering the radical inclusion of the working class. The existence and geopolitical expansion of communist states, the hopes they triggered, and the alternatives they offered had an impact on emerging states. The alternative social system was either a positive example, allowing for more outspoken activity by the social democratic left, or a threat mobilizing all forces to stop “the spectre haunting Europe”. In this way, the proverbial Soviet tanks (in our case, still mere horses) and internal communist movements facilitated the pan-European introduction of land reforms and the establishment of welfare provisions.Footnote 18 Binding people to the state structure beyond directly elected bodies was an explicit aim of welfare provision within the post-World War II order, intended to block both the possible return of fascism and the expansion of communism. But the revolution in Russia triggered a conservative reaction elsewhere, too,Footnote 19 and might have boosted repressive measures and entrenchment by the elite.

Correspondingly, the focus of the present article is the influence on parliamentary proceedings of: (1) internal labour militancy; and (2) the war with the Russian communist state. This impact directly shaped the legislative process and constitution-making and could have ranged from spurring on concessions to workers, to conservative reaction to such measures. The internal unrest and external threat were sometimes coupled in the pro-reform voices aimed at blocking the revolution. Above all, however, they were easily absorbed into the anti-communist discourses of right-wing nationalists. Spiced with anti-Semitism, these discourses set the tone of the post-war debate.

Although parliamentary speeches are not actual law, they offer a partial insight into a “black box” of reconstructing the polity and assigning “places” within it to different social entities, as classes or status groups. It is not possible to pin down a strict causality behind policymaking, as changes in the parliamentary rhetoric did not necessarily reflect the actual shift in the goals pursued by political actors. However, tracing the parliamentary debate offers an insight into how the process of democratizing the polity and reactions against it manifested themselves in political bargaining, policy justification, and decision-making. The parliamentary debate is always responsive to current problems and reacts to ongoing external events. The choices made in speech and the outcomes of oral confrontations delimited the scope for action, the speakable traced the contours of the doable.Footnote 20 Political action through words is an element in the wielding of power, a crucial struggle over interpretations.

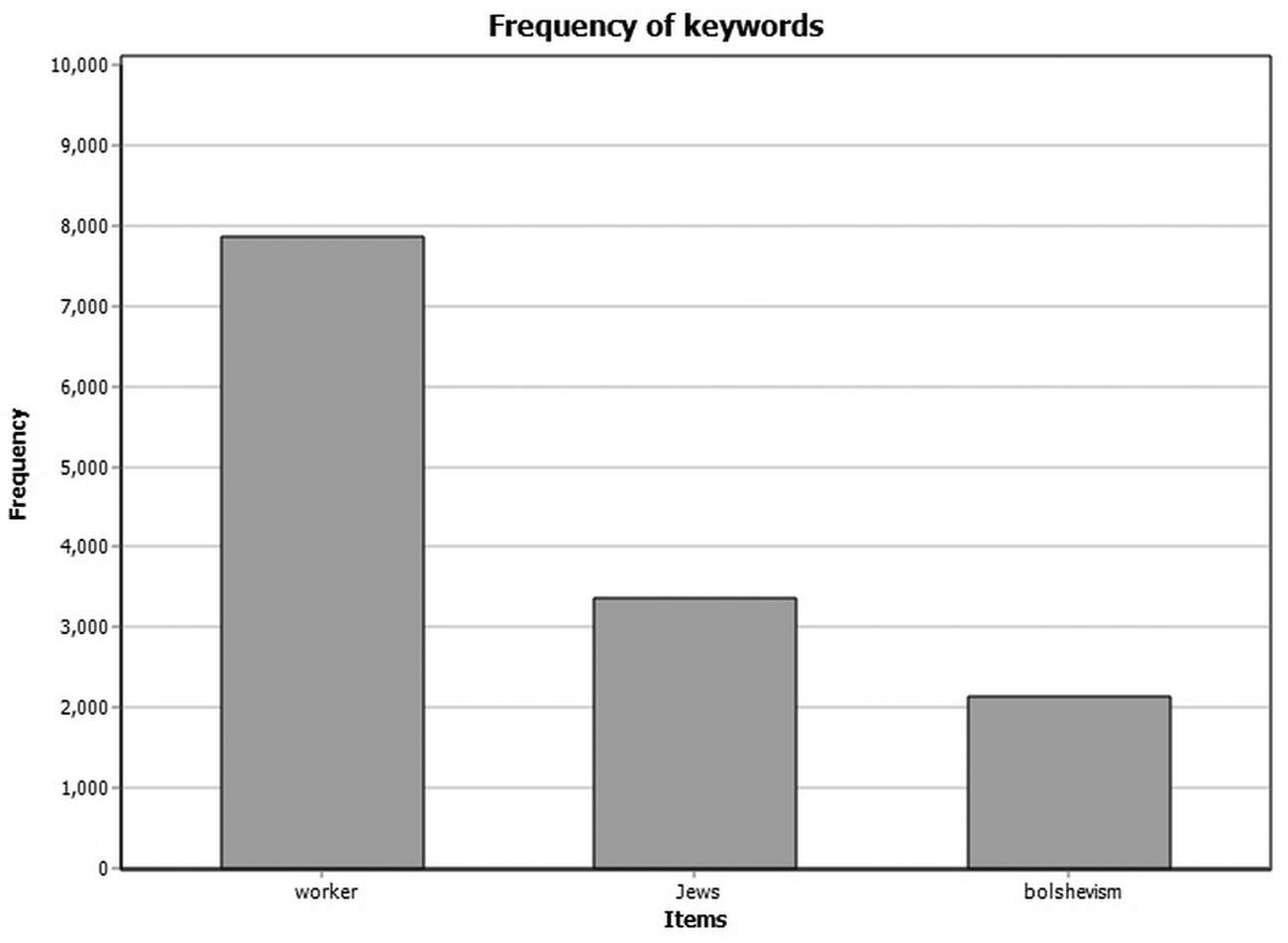

I therefore studied a set of polemical interventions discussing the place of work and workers within the political imaginary, that is, following Martin Burke, a “conundrum of class”.Footnote 21 Recently, the history of concepts and studies of performative speech have converged in research on parliamentary debates.Footnote 22 In this vein, Pasi Ihalainen compared democratizations of parliaments following World War I. While he studied some external factors (such as transnational transfers and international pressure) and included a successor state of the Russian Empire during a period of civil war (Finland), his focus was on the inner causality and timing of the parliamentary process.Footnote 23 In contrast, I am interested in the time sequence as derived from acts of speech and events outside the chamber, such as labour unrest and war. The corpus of debates allows me to trace the debate month by month and to zoom in on rhetorical shifts and pivotal points.Footnote 24 I started with some quantitative insights and text-searching to locate debates of relevance. Later, apart from studying collocations, keywords in context, and the distribution of keywords in time, or along political-party lines, I examined these hotspots, coding them manually in the software. I also coded all instances of pre-selected keywords (such as “worker”, “peasant”, “Jew”, or “Bolshevik”), categorizing the contexts and meanings in which they were used (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Frequency of keywords.

This approach is new with respect to Polish parliamentary sources and connects to similar analyses in other European states in this period.Footnote 25 To my knowledge, the diet transcripts have not previously been systematically studied in a way that combines machine reading and the sequential analysis of events.Footnote 26 Yet, the Polish parliament is an excellent case to investigate the factors shaping rhetorical strategies used to forge the new polity.

POLISH TRAJECTORIES

The Polish lands had already experienced the rise of modern ideologies and mass political constituencies, during the 1905 revolution in Russian Poland and after 1907 with the parliamentary process in Austrian Galicia.Footnote 27 However, it was only after 1918 that the modern political sphere came into being, including fully fledged parliamentary debate. This was when the place and modes of representation of various social groups in the political sphere were carved out. The direct contours of the new state itself were at stake, and in structural terms the Polish state re-emerged after World War I in conditions unconducive to sustainable democracy.

Up to this point, it was a peasant country with a concentrated landed property structure, especially in the eastern part controlled by noble landowners.Footnote 28 The landed elites were entrenched in their positions, additionally strengthened by their long-lasting, self-appointed position as defenders of Polishness. To some extent, their symbolic power had already been assumed by their offspring, the post-gentry intelligentsia.Footnote 29 The commercial bourgeoisie was not numerous and often of non-Polish (usually Jewish or German) origin, perceived as foreign by the nationalizing Polish elites. Thus, the political position of the commercial sphere was weak.Footnote 30 It could not offer a cultural programme attractive to the gentry, which still boasted a strong tradition of the elite democracy of the noble class republic abolished in the late eighteenth century. A strong self-conscious liberal camp failed to emerge.Footnote 31 The conservative parties were unable to secure a foothold within electoral mass democracy after being outmanoeuvred by a vehement, nationalist right.Footnote 32 Polish society was multi-ethnic and already antagonized along these lines. This contributed to the weakness of stable labour constituencies. The Polish Socialist Party (PPS) had been able to stir up mass support before, but it lost momentum because of the early socialist-communist split, factional divisions, and the successful post-1907 nationalist offensive. Despite the party's sharp turn to the left in the final years of World War I, it failed to achieve spectacular results and its electoral support remained weak.Footnote 33

Moreover, the country was in ruins after the “minor apocalypse” of World War I. Industry remained idle without the machinery that had been either evacuated by the retreating Russian administration or seized for the German war effort.Footnote 34 The dissolution of imperial production and commodity chains put an end to demand for locally produced goods. Polish populations were spread across empires as a result of wartime evacuation, exceptionally acute in the Russian part.Footnote 35 Ethnic Poles were drafted into opposing armies with which they did not identify – so the death toll was not easily integrated into any meaningful narrative.Footnote 36 Nonetheless, one by one, all the imperial states into which the Polish-speaking populations were integrated lost the war. First, the now Bolshevik Russia dropped out, and later the central powers were defeated. A unique conjuncture paved the way for the creation of a relatively large state with a parliamentary system.

Polish statehood was burdened with divergent imperial legacies. Since Polish autonomy had been limited, there were no central institutions, as there were within all three imperial states, with the partial exception of Austro-Hungary. Though rank-and-file officials may have had some practical experience in running the state (mostly from Austrian Galicia), the operational institutions and infrastructures were not aligned, with problems ranging from incompatible legal systems to different railway track gauges. Few politicians had previously been active in the Austrian parliament (holding ministerial posts), the Russian Duma, or various political bodies in Prussia. Despite their having invaluable experience, this boosted the fragmentation of the political scene, as many of them cultivated old alliances and animosities. The situation was replete with the tension typical of an emerging state, with multiple centres of power and undefined borders. These tensions were played out in parliament.

Hence, I study transcripts of parliamentary debates held by the first Polish parliament (Sejm) following the creation of the independent state in November 1918. It was in session between February 1919 and November 1922, and its main duty was to draw up a constitution. One was indeed finally adopted on 17 March 1921. This moment, along with the Riga Treaty ending the Polish Bolshevik war signed the day after, ended the crux of the debate. However, the legislative Sejm remained in power, working on important bills until elections could run their course and a new bicameral parliament began its work. The composition of the legislative Sejm changed since the country's borders were not settled – when new territories were included, MPs were also added. Originally, 296 MPs were elected in 1919, but the ongoing co-option of representatives of pre-war imperial parliaments and various auxiliary elections had brought this figure to 432 by the time the Sejm was dissolved. This caused significant power shifts, and parliament remained highly fractured. For example, some political parties sharing a similar ideology but originating in different empires declined to join forces. There was also no clear-cut class-based representation; peasants were catered to by no fewer than four peasant parties, and workers by the socialists but also by the national workers party and the national party of work.

The National Democracy, an ethnic-nationalist political conglomerate, had already established numerous institutions in all three imperial states before the emergence of Poland. In the elections, and in parliament, they acted under the umbrella name of Popular National Union (Związek Ludowo-Narodowy – ZLN). The idea of a national and nationalizing state that would either assimilate (Slavic people) or marginalize (Jews and Germans) minorities appealed to a vast array of social groups, ranging from peasants to aristocrats. Firmly grounded in a nationalist, aspiring middle class and landowning petty nobles, the nationalists defended private property and a conservative idea of the state. In turn, the socialists (Polska Partia Socjalistyczna – PPS) supported the independent state and parliamentary democracy and initially trusted their former comrade, Józef Piłsudski. In the chamber, they aimed at more redistributive arrangements, the protection of workers, and a more inclusive polity with respect to minorities. While the peasant parties unanimously supported parliamentarism and claimed the commanding position in the state for the peasantsFootnote 37 – after all, the most numerous social group – they differed in their acceptance of a concentrated property structure and traditional cultural values. The PSL-Piast was more conservative, declined to stand up against the Church, and advocated more moderate land reforms in comparison with PSL-Wyzwolenie, which in turn was willing to cooperate with the socialists in the name of the popular classes. Christian democracy was not very strong and took the form of smaller parties catering to clerks and workers. They supported labour legislation but often sided with nationalists in other matters.Footnote 38 All in all, the right was dominant. At the beginning of the session, the nationalist camp (32 per cent of seats) could easily count on support from the right-wing peasant faction (PSL-Piast) with 13 per cent, and from smaller centre-right conservative or peasant groups comprising a further 20 per cent.Footnote 39 With 17 per cent and 10 per cent of seats respectively, left-wing peasant parties and the socialists maintained a stable but limited foothold in the legislature but had little say in passing legislation. This patchwork parliament which forged the new state order will be analysed below.

INTERNAL FACTORS: PRESSURE AND AGITATION FROM WITHIN THE STATE

In its first phase, parliament witnessed several waves of internal social turmoil. Labour militancy, strikes, alternative forms of sovereignty, and peasant unrest shaped the parliamentary debate. February 1919 saw a wave of strikes and protests organized by the unemployed. Until July 1919, miners and foundry workers from the Dąbrowa Basin organized workers’ councils, offering an alternative form of sovereignty openly challenging the “bourgeois” state.Footnote 40 Soon after, a radicalized priest and a peasant communist, both of whom later became MPs, launched a peasant revolt in southern Poland in the name of land reform – and proclaimed the so-called Tarnobrzeg Republic. Police repression targeting a dangerous alternative form of power followed. From early on, the core of the parliamentary debate was focused on the legislative order regulating the participation of different social political groups. As early as the third session of the new parliament, the prime minister Paderewski (supported by the right and the centre) stressed, to wide applause, that “the improvement in the fate of the worker will be the main, most urgent and most important issue, and taken up diligently and with care by the Sejm”.Footnote 41 The workers’ issue was rarely absent from the agenda, and the vehement protests ensured MPs were ever mindful of it. “The eyes of the Polish workers are directed towards the Sejm”, noted one socialist MP.Footnote 42 A relatively broad spectrum of political forces agreed that improvements in welfare provisions were necessary for ethical, pragmatic, or just tactical reasons – preventing social degeneration and the political radicalization of the working class.

In the first few weeks of parliamentary proceedings, a key insurance reform was hotly disputed. Some MPs envisioned introducing compulsory and universal health and accident insurance coverage for workers. Also, those on the right with relatively broad worker representation eagerly stressed that “we will unanimously support this initiative and create the best conditions for the worker”. These conditions were defined as the minimum necessary for subsistence, namely “a full stomach and proper shoes”. This initiative did not foster political participation beyond voting, but it did create a sense of integration and citizenship, “happiness in a free, independent Poland”.Footnote 43 PPS members explicitly stated that the victories regarding labour legislation were the result of the protests and firm position taken by labour organizations. It was argued that “only fear of the firm position of the workers at a time when the proletarian movement is growing forced the propertied classes to yield”.Footnote 44 Also, the nationalist right admitted that “industry cannot be set in motion […] because of the conflict between capital and worker” and hence “defusing this tension” by accepting the bill “is unconditionally recommended to the whole Sejm”.Footnote 45 Such unanimity certainly pushed matters forward.

Although not directly addressing the legislative process, the intensified labour unrest in late 1918 and early 1919 influenced the rhetoric and decisions concerning labour legislation. The eight-hour working day had initially been introduced by decree by the Moraczewski government in November 1918 in order to secure the support of the working population. However, it was not until the period of significant internal labour militancy that it was codified in a bill in December 1919, additionally introducing the “English Saturday”, a six-hour working day (to create a forty-six-hour working week).Footnote 46 Also, a quite broad insurance package and labour inspectorate had been introduced before the apogee of the Polish Bolshevik war, but likewise in a period of strong class mobilization. In the early months, the intensified debate on workers and work contains references to workers’ suffering and improvement, but also radicalization. The policy proposals were often expressed using strong modal verbs (must). Verb references to the concept of the worker are often future oriented, and expressed in conditional clauses, signalling hope for improvement but also the threat of neglect (example: “once the working class have a secure existence, other relationships, today so shocking, will also improve”Footnote 47). Deployment of the concept of the worker and the accompanying rhetoric demonstrate how internal labour militancy facilitated the pro-labour legislation.

In this vein, the demands for welfare provision and socialist mobilization were justified also by the threat of Bolshevik radicalization. The PPS clearly positioned itself as a force capable of stopping – and indeed necessary in order to stop – communism. The party had an ambiguous role while clearly aiming at extinguishing the workers’ protest in order to stabilize the new state. For instance, the PPS leadership declared its support for the workers’ councils but later abandoned the idea in order to isolate and eliminate the communists. A similar pattern was evident in Łódź and the Dąbrowa Basin, the two most concentrated and bellicose working-class regions.Footnote 48 In parliament, towards political opponents, this was stated explicitly: “Putting into practice our slogan, ‘work and bread’, means securing hundreds of thousands of citizens for Polish culture, it means securing the workers’ souls from the Bolshevik poison, it means giving the working class a chance to participate in the creation of the Polish state.”Footnote 49

After all, such a position was consistent with the general line of the party, which supported Polish independent statehood as a primary goal and, even after turning sharply left during World War I, still aimed at establishing a socialist system in Poland only as a secondary objective. Such rhetoric of co-optation was a genuine attempt to convince opponents to agree to the proposed pro-worker legislation and other concessions allegedly necessary to keep the state stable and to integrate workers. The true impulse of the heart was often turned into a political argument. During the period of acute conflict in the Dąbrowa Basin, when demonstrations were brutally crushed by the police, PPS MPs took the side of the workers, even while the party opposed further radicalization and worked to extinguish the protest. Ignacy Daszyński, a socialist MP with experience of Austria's imperial parliament, described the police violence as a threat enhancing the danger of Bolshevism:

Let's imagine the moment when, into a humble worker's flat, the bloodied corpse of his father is brought back from a demonstration, or – horror of horrors – the corpse of a working mother, or a small child pierced with a bayonet. Let's imagine the tears, wailing and screams of the whole family over the corpse of the breadwinner. Let's be aware how easy will be the job of a Bolshevik agitator later; he will all the time cover his banner with this innocent blood, calling for revenge on the murderer.Footnote 50

This was not enough, however, to convince the right that the PPS itself was not a Bolshevik proxy. Any political agency of the workers was highly suspicious to the nationalist clergy, who claimed that “if it wasn't possible to prevent the spilling of blood, that is only because you, men of the left, men of the PPS, [who] neglected the appropriate activities. Had you treated the worker issue differently, had you not said that sometimes one must go with the Bolsheviks for the sake of the cause – then no blood would have been spilt in the Dąbrowa Basin [voices: bravo!]”.Footnote 51

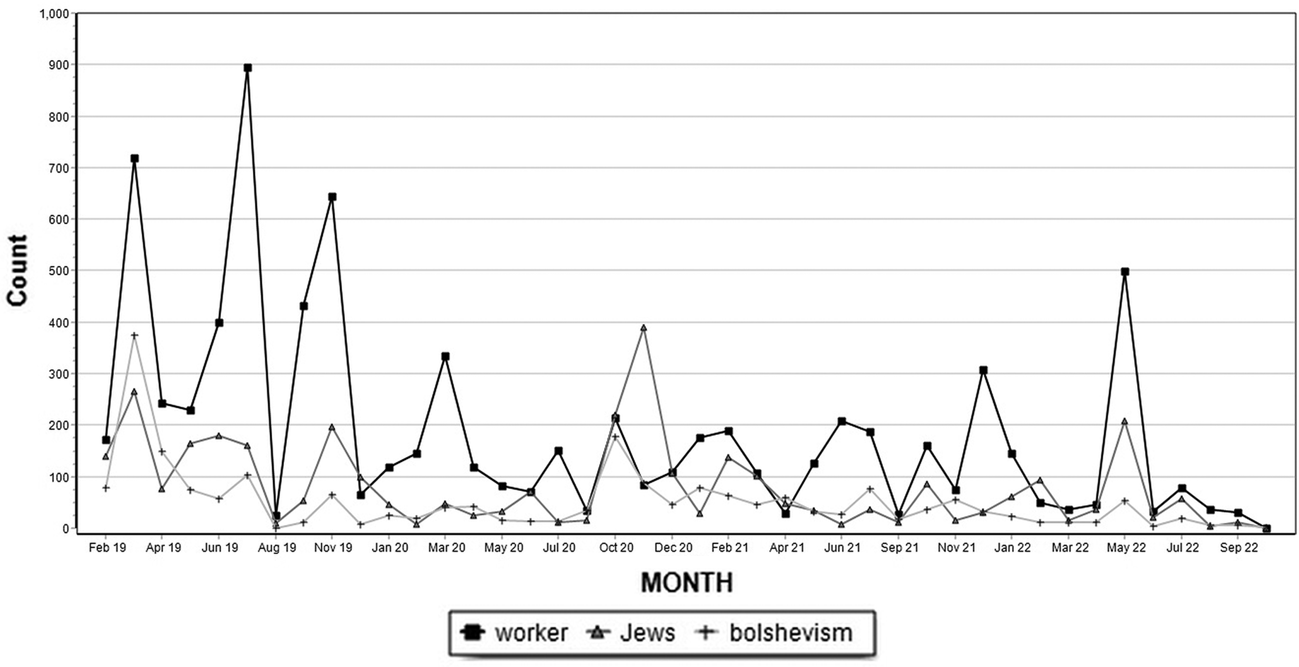

This issue was at the core of the discussion on labour, and both the left and the right used the threat of Bolshevism to support their arguments regarding the workers, albeit for different reasons. The debate on Bolshevism often ran in parallel with the debate on the political status of workers (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of keywords by month.

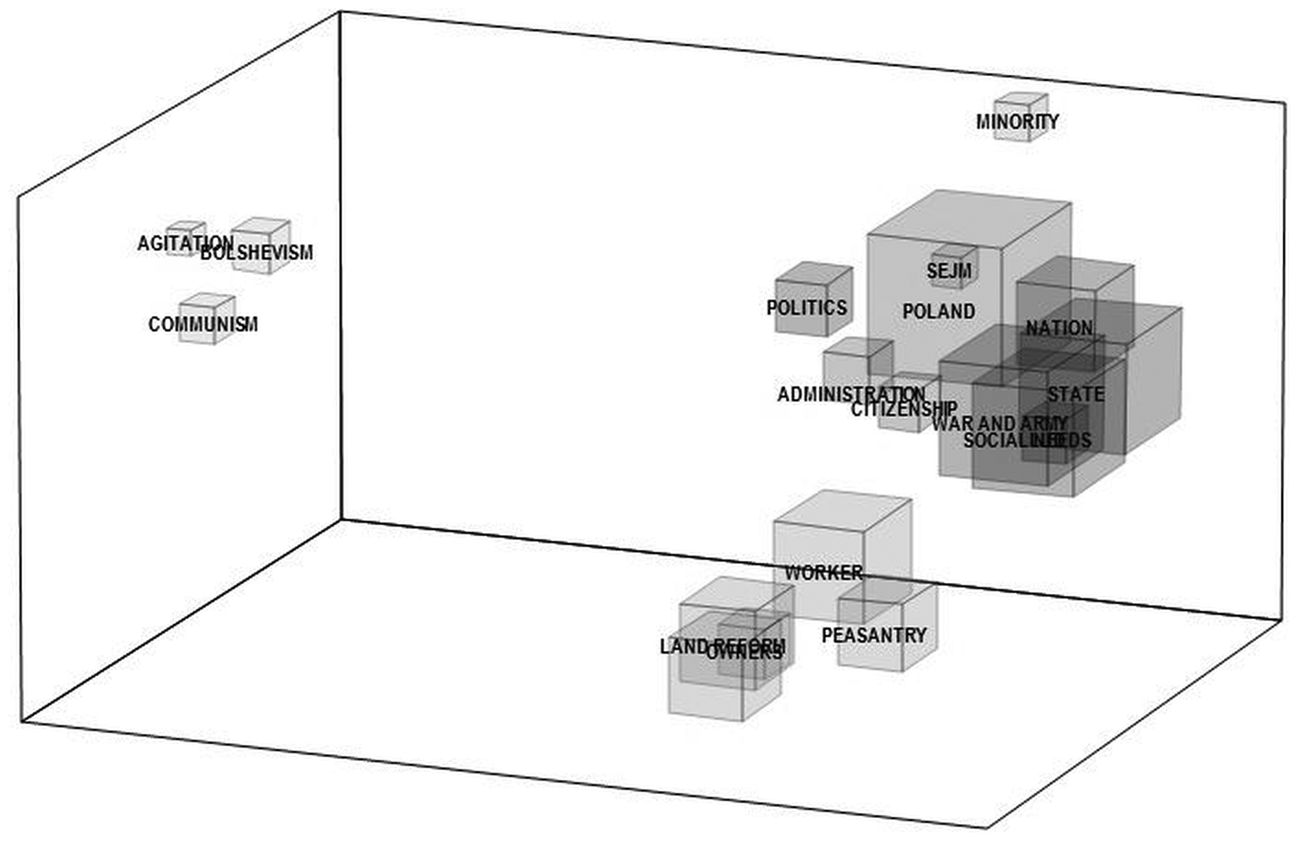

In this phase Bolshevism was not directly identified with workers – neither concept is directly entangled by proximity. Bolshevism forms a distinct topical cluster (see Figure 3). It is a political threat posing a danger from within (communist agitation among the Polish far left) and used in political litigation (both sides accused each other of contributing to the spread of Bolshevism either by supporting the workers’ protest or by suppressing it respectively).Footnote 52

Figure 3. Relationships of key concepts, February to December 1919.

Bolshevism was often a codeword for a real challenge to the state order by the communist left, which was still able to stir up mass support and openly question the parliamentary state order and favour the power of the councils. While expressing his anti-Semitic and anti-communist obsession, the priest Kazimierz Lutosławski was nevertheless right in pointing out the “clearly revolutionary character” of the workers’ councils, which were intended to be the “organs of the working class under the slogan of the dictatorship of the proletariat and the arming of the working masses”, quoting diligently as he did from some clandestine communist publications.Footnote 53 In the political imagination of the right, the menace of “the Bolshevik flood” carrying “misery, misfortune, destruction, and degradation”Footnote 54 was the most serious threat endangering the souls of the Polish popular classes and the integrity of the state.

While PPS speakers attacked the communists without restraint and called for police measures to nip the communist movement in the bud, they vehemently opposed police repression of the workers on the streets. It was important, a socialist MP pointed out, to “convince the workers that they are in the Polish state, that this state and its government are not an enemy of the working classes”. Again, the unrest was blamed on “provocateurs and communists”.Footnote 55 The socialists nonetheless tried to put a stop to the measures against communist agitation, fearing that “under the pretext of communists, a battle against workers’ organization is being waged”. Such a battle, “aimed at crushing the workers’ movement by repression”, would target any political activity, including that fostered by the PPS itself.Footnote 56 This is indeed what happened when the external, real Bolshevist threat came closer.

EXTERNAL FACTORS: THE NATION AT WAR

The war added fuel to the fire, posing an external, existential danger to the state and shaping the second phase of the debate. The initial border conflict with Soviet Russia had escalated into a fully fledged war, which spread rapidly along the hard-to-defend former borderlands of the Russian Empire, especially the Ukrainian steppes and Belarusian marshes. The contested nature of the international class war, combining inter-state conflict with ideological clashes, warranted a special place in the Polish public discourse – the popular mobilization against the external enemy was accompanied by a fear of inner penetration, and external enemies and internal opponents could be easily conflated. The nature of the war was, as will be shown, contested in parliament, where, for various, and sometimes opposing purposes, various actors reframed it as an internal conflict, or even a civil war. These controversies intensified when the peril was no longer a distant prospect of defeat but an actual dissolution of the state and its replacement by a Soviet republic imposed from outside. The Polish army's initial spectacular successes rapidly gave way to grave danger: Polish troops took control of Kiev in April 1920, but in August Warsaw could barely be defended against the Bolsheviks. A few weeks later though, Polish troops were again forcing the dispersed Red Army eastwards.Footnote 57 The swinging pendulum of military fate resulted in rapid shifts in Polish public opinion.

Correspondingly, the next distinct phase of the debate concerning the political and social place of labour came about when the Bolshevik army started to rapidly advance westwards, posing a danger not only to the Polish Eastern Borderlands, but also to areas considered to be the heart of ethnic Poland. With the war, the question of popular mobilization became a core issue in the debate. In order to boost popular support for the war effort, a coalition government of “national defence” was created, in which politicians representing the popular classes – peasants and workers – were given prominent positions. Many key positions continued to be held by the right, in order to bring the propertied classes on board too. Thus, the political representation and agency of the popular classes was an especially and hotly debated topic. The socialist left and peasant parties alike tried to secure concessions for the popular classes, justifying them morally by the toll in the war, and tactically by the need to convince the peasants and workers to contribute to the war effort:

[N]ot only will we create a new military force, […] we will simultaneously create this great moral reserve. I firmly believe that every worker, every peasant, every soldier will stand behind it. This moral reserve can be summarized in a nutshell: Poland will cease to be a playground of reactionary forces, Poland will cease to be a domain of vast landed property and bureaucracy, […] Poland will belong to the people.Footnote 58

This combination of current mobilization and general vision is understandable when we consider the war rhetoric as part of constitution-making. The debate concerned the heart of the problem of what the new Poland would be like, a point made clear by Mieczysław Niedziałkowski, who represented the PPS in the constitution drafting. For socialists, the question of popular mobilization was directly connected with the drafting of the constitution, “the creative idea that will stir the soul and heart of the masses”.Footnote 59 In this way, the war formed a background to the constitutional debate.

The question of the senate's role in the new constitutional order for instance was hotly debated in terms of military mobilization and especially the merits of the popular classes. The debate in the senate was at its most intense at the height of the war and culminated just after the Bolsheviks had been successfully repulsed from Eastern Poland (July–December 1920). The legislative debate was closely related to the political citizenship of workers and peasants. The senate was a key limitation on the broader inclusion of the popular classes in politics and effectively blocked their political impact.Footnote 60 Thus, the issue resurfaced when advantage could be taken of the need for military mobilization to push forward the popular agenda. The left was quite outspoken in stressing its ability to mobilize the popular classes for the war effort and consciously used this fact to promote its political goals: “Not you, gentlemen, but we keep the working masses under the banner of defence of the borders of the Republic; not you, gentlemen, but we ensured that the Polish working class has declared it will defend Poland and its independence.”Footnote 61

Despite the alleged merits of workers and peasants, few direct changes were pushed forward in those days. Wartime was not used directly to reforge the order of the new state or to instigate major social conflict. The constitution was indeed finally adopted, just after the peace treaty with Soviet Russia had been signed in March 1921, but it was not exactly one that “filled the [peasant] cottages and workers’ flats with enthusiasm”.Footnote 62 At last, the bicameral model had been introduced, admittedly with universal suffrage extended to both chambers, contrary to the initial project of the right. Arguments during and just after the war continued to stress the moral ground, calling for inclusion of the popular classes in the broader social and political imaginary shared among parliamentarians. Despite formal equality among all Polish citizens, there was still a long way to go to convince the traditional elites that the popular classes could be considered citizens equal to them. Whereas this indirect influence on shifting the borders of the social imaginary towards broader inclusion may have been real, at the level of direct impact on the legislature, the war did not trigger much change. At the same time, the threat of Bolshevism and actual social turmoil, especially among land labourers, fanned conservative discourse accusing workers and peasants of being potentially susceptible to Bolshevism. Nonetheless, Polish workers and peasants refused to revolt against the Polish state when the Bolsheviks advanced and approached Warsaw in the summer of 1920. Despite the efforts of the Bolshevik-sponsored revolutionary committee that was expected to take power in Poland, the revolution was aborted and the Bolsheviks lost the war.

POST-WAR STABILIZATION

In the third phase, the new statehood stabilized, and political actors reassessed the impact of previous internal and external pressures, harnessing them to foster their political goals. Poland's victory in the Polish-Bolshevik war initially triggered a wave of enthusiasm. In his speech at the end of the war, the Prime Minister Wincenty Witos (PSL-Piast) spoke in a tone of gratitude to the popular classes and admitted that “throughout this critical time, there were no anti-state actions among workers even though the Bolsheviks had spared no effort and money to instigate them”.Footnote 63 Other peasant speakers sought to make more direct use of the popular contribution to the state's survival. “We won the war, that's true. Thanks to the effort of the whole nation”, admitted a peasant MP. Such all-encompassing praise of the victorious nation was immediately qualified by naming specific groups that had borne “the lion's share” in “the sacrifice and merits of the Polish people”. Those who had won the war were, after all, “these nameless thousands of fallen and wounded, these nameless peasants and workers whose bones covered the land of the Republic”.Footnote 64

Such a claim to equal citizenship grounded in sacrifice, not uncommon in post-war societies, did not prevent a slight pushback after the war. When peasant MPs questioned crediting the victory to the undifferentiated nation rather than to the popular classes, the right bent over backwards to name “traitors” among them. “Not the whole nation, but a part takes credit here. One knows that there were people who [shouts from the left: fled to Poznań] not only willingly joined revolutionary committees but cooperated and actively supported the enemy”,Footnote 65 claimed ZLN MP Stanislaw Głąbiński. The fact that the war had been against a nominally far-left force cleared the way for counterarguments blocking more daring steps. For instance, when one PPS speaker said that the Polish landed elites dreamed of the restoration of the monarchy as a way of guaranteeing their privileges, he also pointed to international connections: “this is what is happening in Hungary, this is what is happening among the Russian reactionaries”, he declared; immediately, mocking shouts were heard from the right: “Long live Trotsky!”.Footnote 66

The radical priest Okoń also met with similar resistance, with implied references to his “Bolshevik” sympathies, when opposing the senate. Democratic forces, socialist and peasant-populist alike, supported the unicameral model and resisted the undemocratically elected senate, “an institution taken out of the junk room”, according to Okoń.Footnote 67 “One wonders that there are people who want to dress Poland in a gentry's overcoat [kontusz szlachecki]. Poland would look like this Bolshevik [shouts from the right: in a cassock!] riding a horse while wearing a woman's hat, or walking barefoot in a top hat. […] The senate is a holdover!”Footnote 68

The war cleared the way for targeted attacks on radical peasant and socialist politicians. Right-wing politicians floated various insinuations about Bolshevik commitments or support for the Reds. Even harsher accusations were levelled against Jews, often in the form of disruptive heckling of Jewish MPs. The intensity of these attacks – indicated below in square brackets – and their multiple targets can be seen in a lengthy excerpt from a speech by the Zionist leader Izaak Grünbaum. He was probably the most active defender of Jewish collective rights, often speaking in the name of national minorities in general, and willingly pointed out the anti-Semitic undertones of the war propaganda:

We are waging a war against Bolsheviks and we are waging it with the help of anti-Semitism [Good weapon, it wins]. This is not a normal war between states […] it has features of a civil war [God forbid!]. The people are told: remember, we have to deal with an external but also with an internal enemy [Rightly so]. […] This internal enemy are not only Bolsheviks but also Jews [It's not true, not all of them]. All Jews. [Are you admitting this, Mr Grünbaum?] […] Gentlemen, Bolshevism was not attacked by criticizing its social essence – the official and unofficial proclamations were saying that Bolshevism and Jews are one [That's true!] […] On posters […] a Bolshevik devil embodied in a Jew [Trotsky]. Yes, only Trotsky [Yeah, only Leib] […] The war with Bolsheviks is a war with Jews.Footnote 69

These fragments reveal a constant over-coding of class and ethnicity in the Polish political debate. The war with the Bolsheviks boosted attacks on class politics, imbuing them with anti-Semitic slurs. The left (or even broader: non-nationalists) was often dragged through mud and mire for not being Polish and accused of serving foreign (usually Jewish) interests.Footnote 70 Simultaneously, anti-Semitism was used in anti-Bolshevik propaganda. In parliament, it was the right who played the ethnic card. Its agenda did not openly question capitalism and hence the “economic Jew” trope was clearly less prominent than various forms of “Jewish-commie” libel. This trope was not in fact coined in those days, but it gained unprecedented traction both in parliament and on the streets when Polish military propaganda showed no lack of reluctance to use anti-Semitic undertones.Footnote 71 Such insinuations were also features of less formal commentaries and heckling, as if full-blown anti-Semitism was still considered inappropriate in parliament.

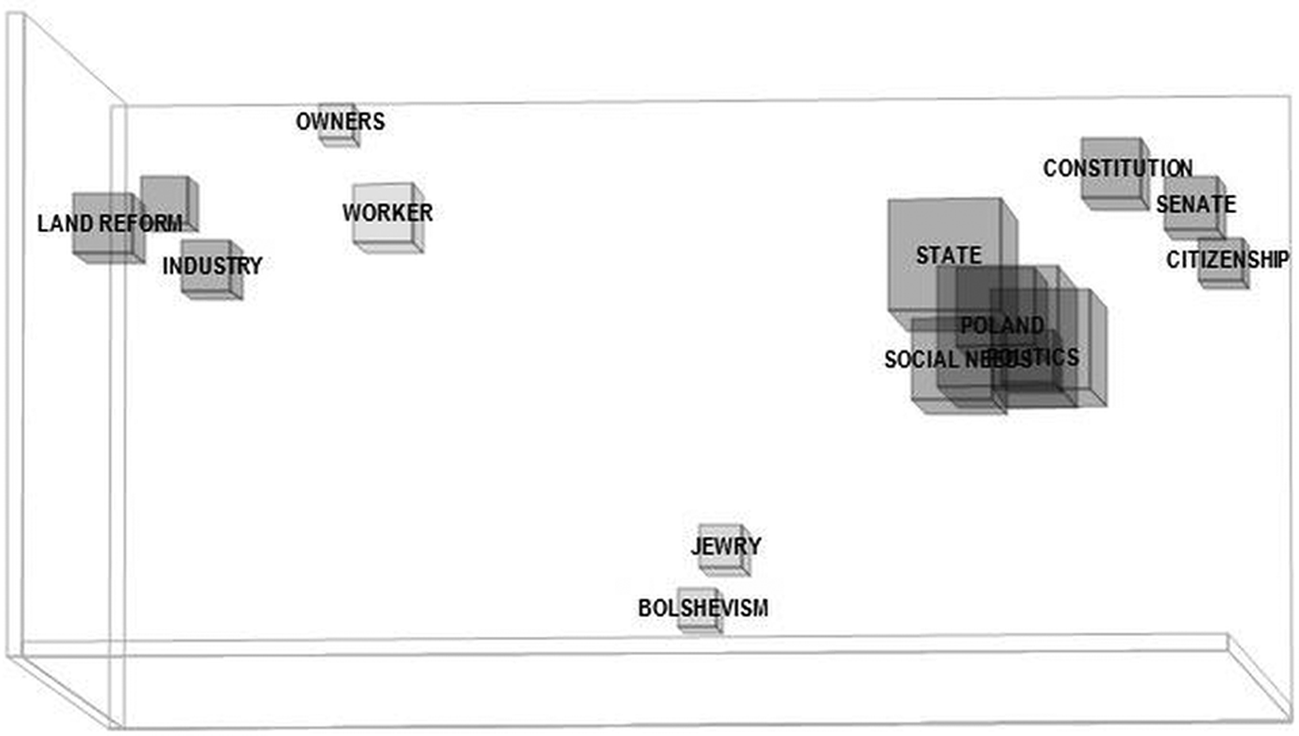

Nonetheless, in speeches by the right (especially the clergy), accusations of Bolshevism or communism often corresponded with accusations of acting in favour of Jewish interests. These were only intensified during the ensuing debate on the pogroms in the war zone and the atrocities committed by Polish military units – the right defended the retaliations as anti-communist measures.Footnote 72 The “convergence” of anti-communist and anti-Semitic language can be seen in quantitative terms by analysing semantic clusters for the period directly after the siege of Warsaw (see Figure 4, and compare this with Figure 2 and the co-occurrence in October 1920).Footnote 73 While minority rights had been hotly disputed mainly as Jewish rights already in spring 1919 (the Versailles negotiations), the anti-Semitic undertones, additionally harnessed against the left, had never previously been so intense.Footnote 74 Their virulence intensified during the war, despite ongoing negotiations regarding the de-escalation of Polish-Jewish conflict in summer 1920. The Polish government desperately tried to consolidate the home front and sought an agreement with Zionist MPs. As soon as the direct danger of war had faded, the negotiations came to naught.Footnote 75 However, anti-Semitic tones loomed larger in October 1920 and continued, for instance during the debate on schools and the details of the new voting procedure in May 1922.

Figure 4. Relationships of key concepts, July to December 1920.

The backlash against the social and political inclusion of the popular classes was not limited to impromptu comments in parliament. When an economic crisis loomed large in early 1921, there was a renewed debate on abolishing the eight-hour working day. Later, in November 1921, two bills were debated: “the bill on temporary measures regarding anti-state intrigues” and “the bill on the persecution of delicts leading to a social revolution”.Footnote 76 Both aimed to remove “the communist weed”, the “hostile, foreign, communist elements”, as the Minister of the Interior, Stanisław Downarowicz, put it,Footnote 77 even though the Communist Party of Poland was already illegal.Footnote 78 As many workers’ journals and organizations had already been targeted, this triggered an outrage on the left, which feared that such special bills would be used arbitrarily to police strike activity. Despite this resistance, the immunity from prosecution of the peasant MP, Tomasz Dąbal, who was accused of anti-state agitation, was lifted.Footnote 79 The already established framework of labour legislation and legitimate bargaining appeared fragile and contestable.

CONCLUSION – THE THREE STAGES OF STATECRAFTING

As I have shown, after World War I the Polish state emerged as a democratic republic with universal suffrage, and it was already subject to pressure owing to social unrest. The plurality of the debate in parliament and the broad participation of workers, peasants, and their representatives allied in “class” parties in itself testifies to the democratizing potential of the moment. In what form the state would eventually stabilize was yet to be determined. The present study has examined the internal and external factors influencing the corresponding parliamentary negotiations. The Polish debate on the political participation of the popular classes can be divided into three consecutive phases, each influenced by historical circumstances.

The first was characterized by the internal pressure fostering political concessions and improvements in labour legislation. Not only did labour militancy put direct pressure on the state structure, but the socialists also used the threat of radicalization to gain greater leverage than their voting power would suggest. The first socialist manifestos and decrees (Daszyński's and Moraczewski's governments) proclaimed pro-labour legislation, which was later vehemently defended. The eight-hour working day, broad insurance, and labour inspection were introduced before the war with the Bolsheviks, but at a time of strong class mobilization. The parliamentary language of those parties supporting the workers used corresponding means aimed at integrating them into the assumed polity.

During the second phase, wartime mobilization reshuffled the hierarchy of issues and promoted national unity. In days when military policing and a conservative backlash were readily accepted, the socialists and leftist peasant leaders could no longer use the threat of revolutionary mobilization to push their agenda. Calls for patriotic mobilization in the name of the state, made by a coalition government, were largely successful. The left used the war input of the popular classes to advocate their political legitimacy, but nevertheless there were few tangible outcomes targeting workers at the policy level. At the same time, wartime mobilization and patriotic fervour encouraged the right to make a reactionary move afterwards. Now the popular classes had to be defended against accusations of supporting the Bolsheviks. The patriotic fervour against the “communist” enemy weakened the domestic (and domesticated) socialists and marginalized popular opposition. In this way, the war helped to consolidate the state and made it better equipped to resist pressure from below.

The third phase saw the re-establishment of order and attempts to politically discount the previous experience of war. Its evaluations were diversified, but all in all the state consolidated in a more conservative and hierarchical direction than many had expected before. At the parliamentary level the socialists were accused of being tacitly affiliated with the Bolsheviks, and their claims delegitimized as a foreign-born threat to the coherence of the state, not without anti-Semitic undertones. The nationalists intensified their critique of working-class political constituencies and attempted to push executive measures targeting them.

The insights from the parliamentary debate can be compared with other countries in the region and squared with the broader findings of historical sociology and large-scale comparative studies. The “social origins” were not conductive to democracy in Poland, and labour militancy rose to prominence as a possible democratic force, while simultaneously posing the danger of a slide into (communist) “dictatorship”, as the classic analysis by Barrington Moore suggests.Footnote 80 As in the whole former Russian Empire, “the two battles – for the civil rights and for the collective rights of labour – had been fought […] simultaneously”.Footnote 81 The working class and the socialist parties assumed the baton of democratization of the state. However, unlike in Finland, the socialists supported parliamentary democracy, even though they were aware of their limited electoral appeal.Footnote 82 Thanks to skilful manoeuvres between working-class militancy and the pro-parliamentarian position, unlike Russian Bolsheviks they successfully co-opted the workers for the state-building project and effectively marginalized the communists, aborting the revolution. This was not conductive to stable democracy though. After being marginalized by nationalists, conservative parties could no longer play a major role as a stabilizing factor and support the social peace and gradual democratization, as Daniel Ziblatt has shown in other cases.Footnote 83 At the same time, the landed elites were aware that the processes of modernization posed a danger for their landholdings, and they were willing to enter into alliances with any force prepared to guarantee their survival as a class and a status group.Footnote 84 This enhanced the power of the vehement nationalists and the anti-Semitic tone of the post-war retrenchment.

The Polish trajectory confirms what Stefano Bartolini has demonstrated: perpetual external danger undermines the emergence of class cleavages and stronger social democratic parties because of the ongoing need to mobilize for national unity.Footnote 85 Moreover, Bartolini argues that states with a well-developed repressive apparatus can easily crush the labour movement. The emerging Polish state is a counter-example – the state was too weak to eliminate labour or peasant resistance by means other than partial co-optation, and it emerged during the peril of war. One should not forget the sequence though. In the Polish case, the possible gains had been made owing to social unrest targeting the weak state, so the later war enabled retrenchment and put leftists on the defensive. Hence, the war did not trigger the democratizing effect documented by Ihalainen, which was relevant perhaps for states capable of subduing unrest and introducing democratizing reforms from above after the war. As this analysis shows, in Poland the external threat of war, waged against a nominally leftist political force, helped the weak state to reduce the significant impact of inner militancy on parliamentary proceedings.