INTRODUCTION

In studying the history of mining, the occupation is usually regarded as an exclusively male activity. However, women have been enormously important, not only in direct and indirect work in the mines, but also in many social, cultural, and economic aspects of the mining communities. In previous and current literature, women are hardly referred to or are attributed a complementary role.Footnote 1 Throughout the nineteenth century and the early decades of the twentieth century, an outlook shared by the unions and later enshrined in law sought to limit the possibilities of direct female labour in the mines and even completely prohibit women from any work in this industry. Removing women from the mines was regarded as socially desirable and an improvement to the well-being of the working class. The resulting discrimination relegated to oblivion a section of the population that had been essential in the economic and social history of mining.

Contemporary mining in Spain offers opportunities for exploring this issue, as mining was particularly intense here during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, placing this country among the world leaders in output of different minerals (particularly during the golden age between 1860 and 1920). Moreover, the search for underground resources covered a large part of Spain, giving rise to different mining areas characterized by a diversity of minerals, forms of extraction, labour markets, and business structures.

The article focuses on direct employment of women in the mines between the mid-nineteenth century and 1936. In Spain, the Civil War lasted from 1936 to 1939 and was followed by the Franco dictatorship, which ushered in a different phase with specific characteristics. The broader function of women in maintaining and reproducing mining activity is rarely taken into account. Female employment was the primary concern of the paternalistic business policies, particularly during the first half of the twentieth century. Analysing this aspect, however, would exceed our objective and the scope of this article.

This study contributes to the literature in at least two ways. First, it quantifies direct female employment in Spanish mining during the period 1860–1920, analysing the distribution of women in the different basins. Using several approaches, we explain the reasons for the variations in participation of women in the mining regions. Second, we study the institutional influences underlying the exclusion of women and their attitude to this process. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. After this introduction, we examine the principal legislation and traditions concerning women in the Spanish mining sector and describe how different social agents pressured female employment. Second, we explain the evolution of the mining sector in Spain during the nineteenth century and first third of the twentieth century. In the third section, we discuss the data available on female employment in the different mining areas and explain the causes of this distribution. Next, we focus on the characteristics of women's work on the surface. In the fifth part of the paper, we analyse women's incomes in this sector and compare them to those of men. In the sixth section, we examine attitudes of unions, workers, companies, government authorities, etc. towards women, strategies used to exclude them and the response of the women, which was conducive to constructing female labour identity. Finally, we reach the main conclusions.

We have based our examination of gender distribution in employment in the sector on Estadística Minera y Metalúrgica de España (EMME), published continuously from 1861 to the present day and providing data on female employment between 1868 and 1934.Footnote 2 The source has given us insight into data for the entire Spanish territory over an extended period. Notwithstanding various shortcomings,Footnote 3 it conveys general evolutions in this sector. Female employment data should be considered with caution. As also holds true for other countries, data on this type of labour were most likely lower than the actual numbers, as complementary tasks performed by women may not have been recorded.Footnote 4

Other complementary sources from the period, particularly the specialized national and international publications, while barely addressing female employment, provide relevant information. A series of reports written to determine the labour force situation is also interesting, particularly the one on Spanish mining in 1911.Footnote 5

With respect to recent Spanish publications, articles on female mining workers are scarce. Somewhat limited texts include Monserrat Garnacho,Footnote 6 Rocío García and Rafael Ruzafa,Footnote 7 and tangential references appear in some studies.Footnote 8

LEGISLATION AND SOCIAL AGENTS AS A PRESSURE INSTRUMENT ON FEMALE EMPLOYMENT IN THE MINES

In Spain, as in the rest of Europe during the second half of the nineteenth century, different opinion groups (e.g. social hygienists, mining doctors, politicians, and the church) started to argue that work in the mines was not suitable for the female condition and advised restricting the access of women to these jobs or excluding them altogether. Women were believed to have “a weak and delicate physical constitution”.Footnote 9 Like children, they needed to be protected. Regulations governing female labour were therefore developed in conjunction with those on child labour.

Legislation regulating female employment in the mines increasingly limited employment opportunities for women and sought to ban them completely from any mining activity. In Spain, during the second half of the nineteenth century, formulating this legislation was complicated. The ultra-liberal trend captured in the Ley de Bases (Framework Act) of 1868 favoured entrusting the organization of mining extraction entirely to private initiatives and therefore opposed state intervention in how companies extracted the minerals.

In subsequent decades, an opposite process sought to regulate and control mining and private investment. Efforts to adopt new regulations were obstructed by the mining employers (particularly in the north of Spain), who formed a well-organized lobby with paid parliamentary representatives interfering in anything counter to their interests.Footnote 10 This power was evident in the Mining Law of 1868, which was enacted as a provisional decree and ultimately provided the most enduring regulations in contemporary mining legislation, remaining in effect for a total of seventy-six years (until 1944).

This did not prevent advances on certain issues, such as regulation of the surveillance required by mine inspectors. This function had been addressed in the different regulations of the nineteenth century but was not included until the enactment of the Mining Police Regulations of 1897,Footnote 11 the first regulation in Spain that expressly prohibited women from performing underground tasks (together with children under twelve). This legislation was introduced by the State, which, at the end of the nineteenth century, implemented a series of social measures influenced mainly by legislative amendments across Europe.Footnote 12 The goal was to control an increasingly conflictive labour movement.

In Europe, women working in the mines were a subject of controversy for much of the nineteenth century, starting in Great Britain with the well-known survey “The condition and treatment of children employed in the mines and collieries of the United Kingdom” (1842). Description of conditions and characteristics of life in the mines had an impact on policies and public opinion, and that same year the Mines and Collieries Act 1842 excluded women and children under ten from underground work in the mines.Footnote 13

The discussion about the appropriateness of this female employment spread across the European continent. Particularly noteworthy is the scope that this controversy had in Belgium, where several studies were conducted by the Académie royale de Médecine on the issue.Footnote 14 Remarkably, these studies did not mention any physical inconveniences to women working underground.

Gradually, the opinion that women should not perform this type of work became more widespread. Angela V. John has classified the various arguments invoked in three groups:Footnote 15 physical (e.g. safety, health, changes in the female image); moral (e.g. interacting with men underground, the clothes worn); and economic (cheap labour taking jobs from men or reducing their wages). In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, emulating British legislation, similar Acts were therefore adopted to prohibit women from working underground throughout Europe, for example in France (1874),Footnote 16 Belgium (1889),Footnote 17 Germany (1900),Footnote 18 Italy (1907), and Greece (1912).Footnote 19

In terms of Spain, we find no evidence of concerns about this issue. On the one hand, as we have already mentioned, hardly any women were employed in the areas underground.Footnote 20 On the other hand, employers were interested mainly in limiting State intervention and audits and keeping taxes on property and the minerals extracted low. Meanwhile, the labour movement arose and instigated serious unrest over the harsh conditions in the mining basins. In the late nineteenth century, banning female workers from the mines was not a central goal of unions and labour parties in Spain, which did not seem to have taken a stand on this matter. Understandably, therefore, the first Law regulating work by women and children (13 February 1900) did not entail ratification of the ban on underground female labour in the Regulation of 1897. Instead, male and female workers alike under sixteen were prohibited from working underground (Article 6). Unlike the previous ban on women by the Mining Police Regulation, these new laws led to protests, particularly in the basins in Southern Spain, where child labour was widespread.

What was the attitude of the institutions towards female employment in the mines? Legislation to protect female labour, as held true for Spain's social legislation overall,Footnote 21 was aimed not at improving working conditions among women but at preserving their social role and, particularly, their reproductive functions. In this sense, the Law regulating work by women and children 1900 addressed leave for childbirth and breastfeeding (Article 9).

The ban on underground female employment in 1897 was only symbolic and went unnoticed. A publication from 1905, in which the Institute of Social Reforms presents an exhaustive review of Spanish regulations in this matter, does not mention this ban.Footnote 22 Miners’ associations were similarly unaware of it in 1909, when they protested to the government about work in the mines and demanded that female and child labour be abolished.Footnote 23 No new regulations of female underground employment were introduced, until the Royal Decree of 25 January 1908, which prohibited men under sixteen and women under twenty-three from performing particularly dangerous tasks. Women under twenty-three were excluded from certain activities related to extraction, transport, and other services.Footnote 24 As indicated by G. García,Footnote 25 this ban on women “was not so much related to being under the legal age as it was to the biological fact […] for the worker and her offspring”. The law of 8 January 1907 reforming the law of 13 March 1900 introduced regulations concerning pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding, revealing the focus of female social legislation on these issues.

The ban on female labour in underground tasks reappeared in the law of 27 December 1910 (Article 14). Referring to working hours in the mines, this law is somewhat strange, as this would ordinarily have figured in amendments to general legislation on labour by women and children. This ban seems more indicative of pressure applied by the miners’ associations in 1909 than of concern on the part of the public authorities about this matter. The disinterest of the institutions is logical, as underground female labour had largely disappeared from Spanish mines. Maternity received the most consideration and was the main focus of the legislation, as is clear from the mining code drafts of 21 October 1912 and 26 June 1914 (we have already mentioned the problems in Spain with enacting a mining law), which expressly indicate that the protective laws relating to female labour will be complied with, “particularly with respect to the terms that should be met in periods of pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding” (Article 238 in both drafts).

From the 1910s, unions and labour parties adopted an active and clear position with respect to the gender issue in the mines. Like in Great Britain in the 1880s and subsequently in the international labour forums at the turn of the century, total expulsion of women from the mines, both underground and on the surface, became one of the workers’ demands. At the International Mining Federation Congress held in Salzburg (Austria) on 8 June 1908, the “legal prohibition of women being employed in the mines” was agreed.Footnote 26 The majority of European labour organizations accepted this course of action. In Spain, trade unions supported these decisions, and in 1909 they argued that the legislative amendment on labour by women and children served to “conserve the race”,Footnote 27 seeking to ensure family reproduction. The same arguments used in the nineteenth century with respect to this issue were invoked: “The physical constitution of women, which is weaker and more delicate that that of men” and on “grounds of morality,” which “opposed men and women working together at the bottom of the mines”.Footnote 28 The international labour agreements materialized in the Underground Work (Women) Convention of 1935 (effective from: 30 May 1937) of the International Labour Organization (ILO), in which Article 2 read: “No female, whatever her age, shall be employed in underground work in any mine.”

These positions have been derived from reviewing the daily El Socialista. This newspaper was the official means of communication for the Spanish Socialist Workers Party (PSOE) and the General Union of Workers (UGT), which was the majority union in the mining sector between 1900 and 1912. The issue of female workers in the mines is hardly mentioned and is referenced only to indicate ratification of international agreements, as in the case of the International Mining Federation Congress of 1908.Footnote 29 It is also mentioned in the proposal of reforms to legislation on labour by women and children at points relating to maternity leave and accommodations for breastfeeding.Footnote 30 In practice, no interest is apparent regarding the situation and regulation of work by women in the mines. Generally, women were not a problem. They had been excluded from underground tasks, and the unions sought to curtail their activity in the mines. Problems did arise, however, in places where female labour was commonplace, particularly with respect to two issues. First, women were a cheaper source of labour (see below), which led to reduced wages for external mining tasks; second, they competed with boy workers, who could be employed in the mines with the prospect of long-term jobs and promotions (which was not the case for girls). These issues will be discussed later.

Although employers did not express a clear opinion about female labour in the mines, they developed a distinctly paternalistic new strategy in the main mining nuclei. Above all, they faced a worrying increase in conflicts in the mines (together with the problems of mineral prices) and were concerned about the reproduction of this specific workforce. They sought to do away with dual work, establish permanent workers, and develop a family strategy. They focused their efforts on the male workforce and did not resist the exclusion of women workers. Significantly, the Marquis of Comillas, one of the most prominent supporters of this mining paternalism, did not hire any women in the mines under his control. They were very important in the functioning of the mining economy but not in direct productive activity.

THE SPANISH MINING INDUSTRY

In the nineteenth century, the mining boom on the Iberian Peninsula positioned Spain for several years as the world leader in the production of minerals such as lead, mercury, copper, and manganese and near the top in the production of zinc and iron. At the beginning of the twentieth century, coal extraction was particularly noteworthy and was the principal product of the Spanish mining industry throughout this century. Mining took place across different areas of Spain and was among the most dynamic Spanish exports.

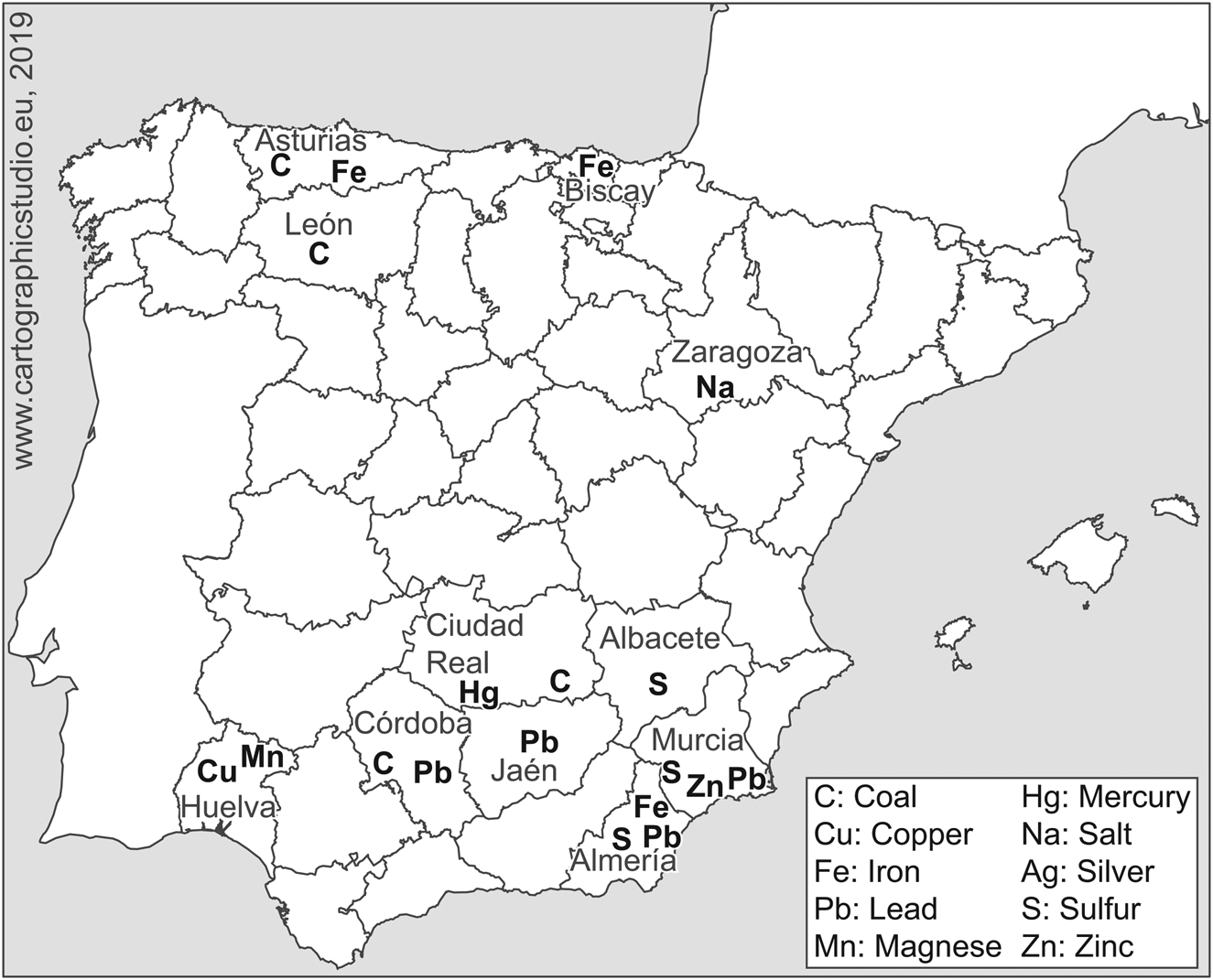

Modern mining began in Spain in the Gádor mountain range (province of Almería) in the 1820s. The abundance of lead deposits in this mountain range and international demand for metals led contemporary restrictions to be eased at that time with respect to free mining and particularly smelting minerals. This production made Spain the second-largest producer in the world (after Great Britain) during the first half of the nineteenth century. It was conducive to modern regulation of the sector, sanctioned by the enactment of the Mining Law of 1825, which enabled private initiative in underground mining.Footnote 31 At first, these changes had a limited impact on the development of mining. Only in 1849, after the discovery of argentifero lead in the Almagrera mountain range (also in Almería), did large-scale contemporary mining of minerals in Spain truly get under way (Figure 1). Initially, mining was fundamentally based on extracting lead minerals in the southeast of the peninsula, the Almería-Murcia-Jaén triangle (briefly positioning Spain as the world leader in lead production between 1871 and 1880).

Figure 1. Map of Spain with the principal mining basins.

Mineral extraction extended progressively throughout Spain. Because of transport problems, the activity initially took place mainly in basins located close to the coast. During the second half of the nineteenth century, the activity extended to other minerals that gradually surpassed the traditional supremacy of lead: coppers in Huelva (particularly the Riotinto mines), iron minerals (mostly from Biscay), zinc from Santander, and particularly coal from Asturias and León. In the twentieth century, most of the production and mining workforce in Spain concentrated on these fossil fuels. Almadén (Ciudad Real), the most productive mine of mercury minerals (cinnabar) in the world, was a special case.Footnote 32 This specific mineral was located in a particular deposit that the State had mined since the seventeenth century.

The mining initiative initially subsisted from national capital, with foreign investors (mainly French and English) dominating mining of certain minerals and basins in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. At the end of the nineteenth century, the mining industry accounted for around 100,000 direct jobs, peaking during the period of our study at 131,943 workers in 1907.Footnote 33 Although in some areas mining was a traditional occupation, in the nineteenth century a good part of the labour markets emerged from the agricultural sector. The complex process of adaptation, training, and establishment involved a variety of factors, making the labour force map of the Spanish mining industry more heterogeneous.Footnote 34 In this process, the space accessible to female workers was also remodelled. In shaping modern industry in Spain, traditional practices from the previous labour markets (agricultural and mining) coalesced with the new demands of the mining sector. In the basins where demand for labour was high, the principal objective was to settle the workforce and consolidate a mining proletariat.Footnote 35 A noteworthy case is Asturias, where companies imposed paternalistic industrial policies on the workforce and their families.Footnote 36

As in most countries, Spain's mining industry was not uniform. There was no single mining sector but a diversity of mining areas, characterized within the scope of this study by different labour markets, traditions, and social practices that influenced the female employment indices. The Spanish mining areas were also distinctive in the prevalence of either underground or opencast mining, respectively. Underground mining was more technically complex and required greater specialization and skill, giving rise to many job categories both inside and outside the mine. Furthermore, working inside the pits required a predisposition and training attainable only through years of working from a very young age. In opencast mines tasks were simpler and required a lower level of specialization. Consequently, there were far fewer job categories, and the labourers were predominantly unskilled.

Generally, the most important Spanish mining areas were:

– The southeast (Murcia, Almeria and in part Jaén): characterized by lead mining, underground work, extreme automation of extraction, and low profitability of the concessions. This required specific forms of organizing mining tasks with a remarkably high incidence of child labour (the highest in the mining industry of the Spanish peninsula). This contrasts with the practical absence of female labour, for which the rate was lowest in all of Spain.

– The mining industry of Biscay was focused on extraction of iron ores and was run by medium-sized companies. The system used was open-cast mining, and over ninety per cent of the – largely unskilled – workers performed their tasks on the surface. To some extent, mining constituted a bridge for emigrants looking for work in the industrial area of the Estuary of Bilbao. The share of female employment was very low.

– In the southwest of Spain, especially in the province of Huelva, copper pyrites were mined. Here, large foreign companies were in control, such as Tharsis and Rio Tinto. High percentages of minerals were extracted from large open-pit mines. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, substantial immigration consolidated the populations residing around the main deposits. Female employment was the same as the national average. Manganese mining is interesting in this respect because of the higher percentages of female employment, as we shall see further on.

– Coal mining was concentrated mainly in the north of Spain: Asturias and to a lesser degree León. Many small and medium firms were formed with national capital. The majority of the mining was conducted underground. The longstanding mining tradition in Asturias was characterized in the nineteenth century by a workforce made up of what were known as “dual workers”, who combined mining with agricultural jobs. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the mining boom in this region shifted this balance, and companies adopted measures whereby the workers were employed only in mining jobs.Footnote 37

ESTIMATING THE NUMBER OF WOMEN IN THE SPANISH MINING INDUSTRY, 1868–1934

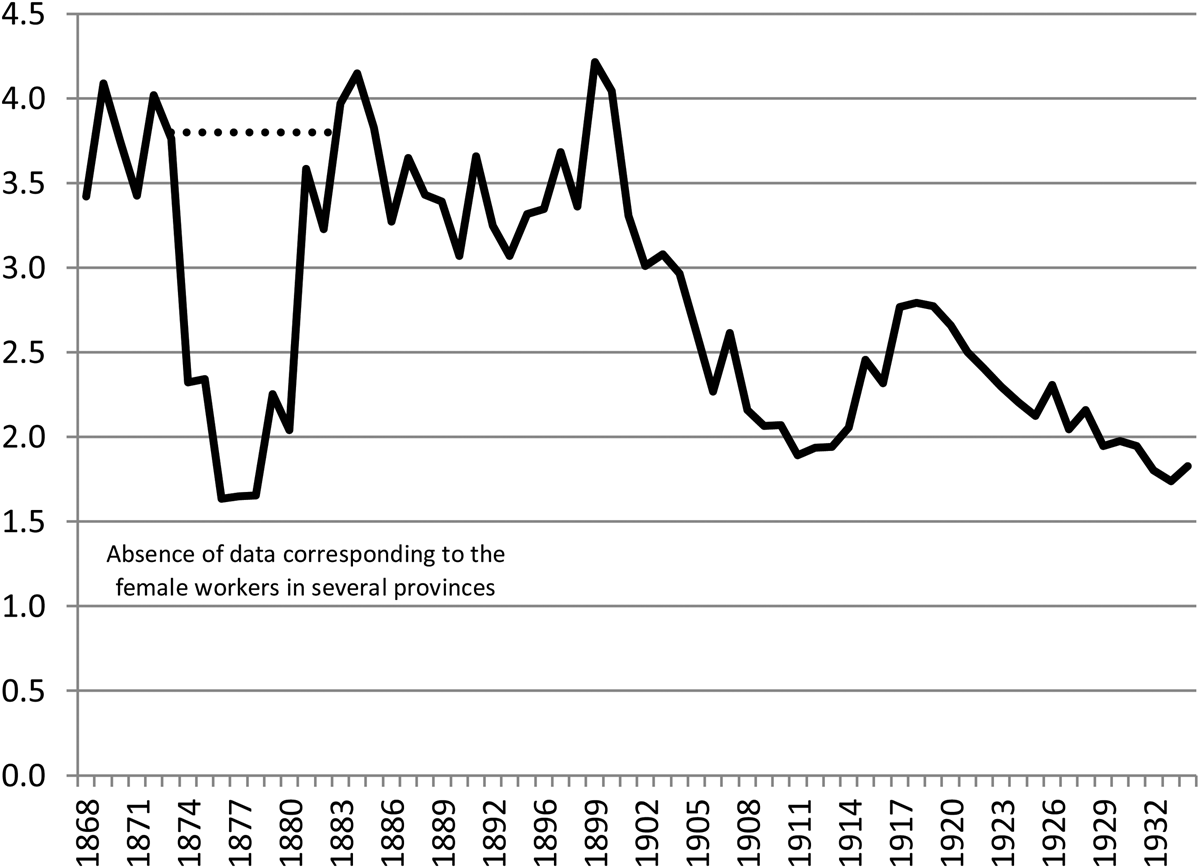

The overall number of women employed in Spanish mines was low, but, as we shall see, it was on a par with their representation in the rest of Europe. According to the EMME, the total number of women employed rose in response to the increase in mining during the second half of the nineteenth century from one thousand five hundred female workers in 1870 to over 3,000 at the turn of the century. The year with the highest number of female workers recorded in the EMME was 1918, with 3,674 (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 2. Percentage of women employed in the Spanish mining sector, 1868–1934. Source: EMME of the respective years.

Table 1. Numbers of women employed in the Spanish mining industry, 1868–1934.

Source: EMME for the respective years.

The percentage of female workers in the total mining workforce gradually diminished over the period considered in this study. During the nineteenth century, the percentage of women working in the mining industry oscillated between 3.5 per cent and four per cent. During the first decade of the twentieth century, this share declined steadily to around two per cent. Following a brief recovery during World War I, their share diminished again, reaching a nadir at less than two per cent in the 1930s. The low percentages of female workers are similar to those noted in other European countries. A.V. John estimates that in 1841 women and girls employed in the mines in England accounted for around four per cent, and this percentage declined throughout the nineteenth century.Footnote 38

Before analysing the employment figures, the elements for evaluating female participation in the work in the mines need to be specified, differentiating between underground and surface mining. The minerals are first extracted from surface outcrops. When these do not exist, or when the surface deposits have been exhausted, the minerals must be sought underground. This work can be carried out in two ways: through shafts and pits or through opencast extraction. Technical, geological (disposition, type, and characteristics of the minerals) and financial factors or ownership of the concessions determined which system was used. The general trend favoured opencast mining, enabled the use of new earth-moving technology, and gave rise to high productivity. By contrast, underground mining required a higher percentage of skilled labour and operators willing to go down to the bottom of the mines, where the accident risk was greater.

But the mining activity did not consist only of mineral extraction: the products obtained had to be prepared for sale. Usually, selection (Figure 3), cleaning, and even concentration through different procedures (traditionally gravimetric methods until flotation systems were developed) were necessary. Furthermore, many activities in the areas surrounding the mines depended on a range of variables and were necessary to develop this production. They may be related to the transport (inclined planes, overhead cables, mining trains); preparation and repair of tools, machinery, or other products necessary for extraction; manufacture of elements necessary for packaging or sale of the products; in general, a series of auxiliary services for maintenance of the mines and the personnel working there.

Figure 3. Female workers in the Biscay mines selecting iron ore. First third of the twentieth century.

These tasks were important, as they offered greater employment opportunities for women. The line distinguishing mining tasks from non-mining tasks is very fuzzy. For example, some companies fed their miners and also employed those providing this service; in the Huelva de Rio Tinto Mines teachers and cleaners were on the payroll; in the Asturias coal mines, many girls started as water carriers (providing water and other services to the miners).Footnote 39

The overall expansion of open-pit mining was not linear and included advances and setbacks. This held true for Spain during the period studied, in which the number of workers employed in surface mining increased progressively during the nineteenth century (thanks mainly to the iron mines in Biscay and the copper in Huelva). In 1902, these miners were 57 per cent of the total workforce employed. In the following years, the trend reversed and the percentage of those employed on the surface progressively decreased: from 51 per cent in 1915 to 45.6 per cent in 1920, then to 45 per cent in 1925 and 36.7 per cent in 1933.Footnote 40 The changes arose from shifts in the types of mineral extracted. Previously, the mining sector in Spain had principally focused on extraction of minerals (lead, iron, and copper). Now, it was dominated by coal, which, due to its characteristics, was extracted mainly underground. As we shall see further on, this factor is significant for female employment figures.

Traditionally, few women were employed in the mines in Spain. As was the case elsewhere, old superstitions could be detrimental to the output of a mine.Footnote 41 In any case, the high proportion of male workers in most of the mines in the nineteenth century related mainly to the way the labour markets developed, involving the transfer of the agricultural population to areas with mineral resources and a certain degree of isolation. Initially, most of those moving there were men.Footnote 42 This explains the low percentage of women in the new basins of activity during the mining boom of this century. In other places, such as the mines in Asturias, the mining tradition was closely linked to agricultural families, who worked in both sectors and increased participation by women in mining tasks. Initially, coal deposits near the surface were mined and over time deposits were extracted from deeper layers. In this transition, women may have continued to work in the pits underground.Footnote 43 L. Mercier and J.J. Gier seem to be correct with respect to Europe: “women miners were prevalent in areas where women had worked in shallow pits that had previously been part of preindustrial family operations, which included children”.Footnote 44

No series reflect the work of women inside the mines for the nineteenth century. Global figures are available for 1889,Footnote 45 when only sixty-five women were listed as employed underground in the Spanish mines in three mining basins: Águilas (Murcia),Footnote 46 Belmez (Córdoba),Footnote 47 and Remolinos (Zaragoza); none are listed for the mines of Asturias. In Remolinos, a deposit of rock salt was being mined and there was an unusual case of female employment: in forty-one mines, the total of 154 underground miners included forty-eight women. Other sources have revealed that these women packaged the salt previously extracted and ground. Since this task was easily performed in the pits, it took place underground.

In short, practically no women were engaged in underground mining, and they gradually disappeared throughout the nineteenth century (before they were banned in 1897), characterizing underground mining as a wholly male activity. Subsequently, women worked occasionally in the interior of the mines, as happened during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939).Footnote 48 Only in 1984 were women granted access to the mines on terms equal to those of men, as we shall see later.

WORK BY WOMEN IN THE MINES: ON THE SURFACE AND LOW-SKILLED

As women were forbidden from working inside the mines, analyses of female employment should address the number of workers employed in tasks on the surface. The problem is that no data track the evolution of this kind of employment in the nineteenth century. The only information available covers the first third of the twentieth century. We have tried to make an estimate by applying the percentages from the twentieth century for some minerals to labour force data available for the nineteenth century. To avoid lucubration, these calculations cover only certain provinces and not the entire workforce.

Nevertheless, the data for the twentieth century are significant, as they shed a different light on the previous scenario (Figure 4). The low percentage of women employed did not indicate a gradual decrease in the female workforce; rather, it fluctuated, hovering around five per cent of the total surface workforce. The reason the percentage of women remained similar in this case but declined in the previous one is that the percentage of the workforce employed in underground mines rose in the twentieth century. This increase in work now forbidden to women led to a decrease in their total share. However, their presence in tasks they were permitted to perform does not seem to have decreased.

Figure 4. Percentage of women employed in surface tasks of Spanish mines, 1902–1934.

The averages for female employment are similar to those in the European mining sector. Angela V. John provides figures of 6.3 per cent in 1874, 5 per cent in 1880, 4 per cent in 1890, and 3.1 per cent in 1900 for the surface tasks for coal, iron, shale, and clay mines.Footnote 49

On the surface, the women's tasks related mostly to selection of the minerals and their concentration, usually in the washing processes. According to a description of the Murcia ore field: “The women work in the establishments or workshops for the mechanical preparation of the minerals (some are engaged in the sorting of the minerals and others in their washing […]) only during the day; never at night.”Footnote 50 These tasks were similar to those carried out in the rest of Europe.Footnote 51

However, the average female employment figures are composed from very different scenarios that relate to a variety of forms of mining. There is no single mining activity. Mining is organized according to different factors (type and composition of the minerals, geographic location, labour market, distribution of ownership, etc.), which change over time (evolution of the markets, technological changes, legislative changes, etc.). In addition, customs and traditions gave rise to very different assessments, depending on the areas of the possible female activity in the mines.

As previously mentioned, the size and variety of mining in Spain covers a very broad scope. This enables us to study the determinants of female employment in the mines in depth and indicates highly significant variations in female employment between the different territories (Table 2). For example, in the ore fields of the Cartagena-La Unión mountain range or Biscay the percentage of female employment averaged between 0.1 per cent and 0.9 per cent, respectively. In the Asturian coalfields this figure reached 14.5 per cent, and, in some years, women exceeded 20 per cent of surface workers (1902, 1903, 1904, and 1907).

Table 2. Percentage of women employed in surface tasks in the mines of Murcia, Jaén, Biscay, Huelva, Asturias, Córdoba and Ciudad Real, 1902–1934 in five-year periods.

* We have estimated the figures by using the percentages of the labour force distribution in surface tasks for 1902.

Source: EMME from 1902 to 1934.

What were the reasons for this enormous difference in female employment between mining areas? The answer is complex. The multiple factors are not all economic. The type of mineral being extracted is one possible explanation. Analysing female employment for the principal products reveals minor differences. Between 1902 and 1933, the percentages of women employed in surface tasks for the respective products averaged: lead 3.2; iron 1.1; copper 2.8; mercury 1.5; zinc 10.8; coal 11.0; and sulphur 8.9.Footnote 52 Analysing the distribution of these figures across the areas where mining took place, however, indicates enormous differences. In Asturias, for example, where female employment was high, production was focused on fossil fuels (coal) (Figure 5). In the adjacent province of Leon, coal was also mined, but percentages of female employment were very low. In the early decades of the twentieth century, female employment in surface tasks fluctuated between one and two per cent here. As tasks for other minerals, reflect a similar pattern, both the type of mineral and other factors seem to have made a difference.

Figure 5. Women loading coal wagons in the “Mosquitera” mine (Asturias), c.1925.

In our mineral-related analysis of female employment percentages, manganese and sulphur are noteworthy. Manganese was mined principally in the province of Huelva, where, as we have seen, the percentage of female employment approximated the Spanish average. In mining manganese, however, percentages of female employment were the highest in Spain, with an average female labour force of the total surface workforce between 1902 and 1934 of thirty-three per cent and exceeding fifty per cent in some years.Footnote 53 The reasons are related to the need to prepare these minerals for sale, once they have been extracted. But other minerals were also mined, such as lead, where almost all workers were men. Therefore, the reasons must derive from organization of the work and the mining companies. In this case, demand for the mineral was highly volatile, and it was extracted by small companies or even quadrilles, which, when prices declined, worked in the gleaning and exploitation of slag heaps. Mining work was combined with other activities and was family-based. As Joaquín Gonzalo Tarín describes:Footnote 54 “the men were engaged in the extraction of the ore and other activities which required energy, while the women and children were engaged in the classification and other tasks appropriate for their muscular strength”. In summary, the dual family work meant that due to division of labour in this product female participation was high.

Another distinctive case was sulphur, which was mainly mined in the provinces of Albacete, Murcia, and Almería. Here, the percentage of children was the highest throughout the Spanish mining industry (30–40 per cent between 1870 and 1923).Footnote 55 As mentioned, the percentage of women was also significant (8.9 per cent between 1902 and 1933). Once again, these mines were operated by families and were time-sensitive (depending on product demand), with extraction occurring alongside selection, smelting, and preparation of products for their sale. One of the tasks in which women were engaged was the manufacture of baskets and sacks for the sale of sulphur.Footnote 56

Wage levels of men might also explain higher or lower levels of female employment. Poorly paid miners would be more inclined to encourage their wives to take jobs, leading female employment in the mines to increase. Wage data for the first third of the twentieth century,Footnote 57 however, indicate that in Murcia, one of the provinces where male wages were lowest, female employment in the mines was practically non-existent. On the other hand, in Asturias male wages were among the highest (Asturias placed 2nd, 1st, 2nd, and 4th in the remuneration rankings for 1914, 1920, 1925, and 1930, respectively), but the percentage of women working in the mines was higher.

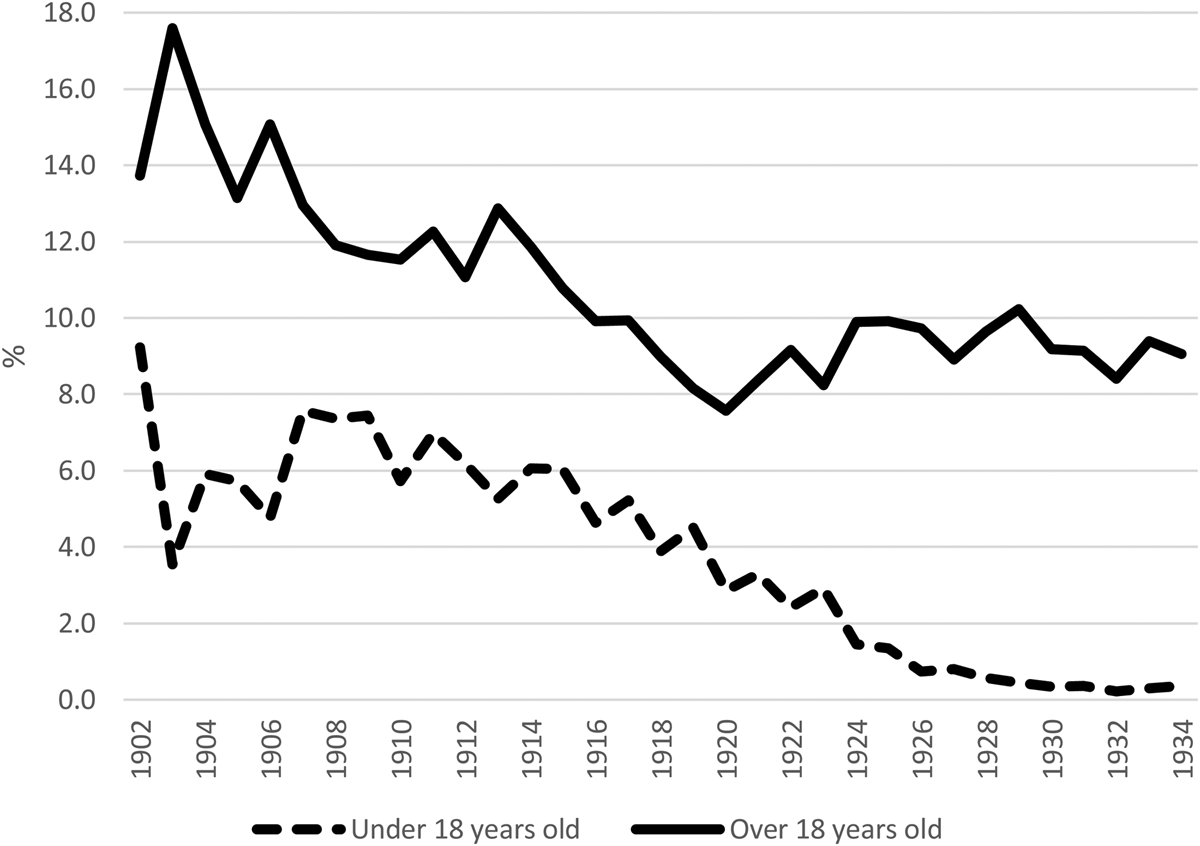

Another possible factor in female employment is the age at which they worked. While no detailed data are available in this respect, the statistical source used lists numbers of workers under eighteen for men and women, respectively, between 1902 and 1934. The averages for women at some moments approach fifty per cent. Percentages of male child labour are lower (Figure 6). At the end of the period considered the two vectors converge. This will be commented on later in the text.

Figure 6. Percentage of workers under eighteen in Spanish mining by gender.

These figures reveal that women worked in the mines while they were young and usually stopped this kind of work when they married. Women employed in the mines usually met with disapproval. When they entered a relationship or married, most had to leave their jobs, as the testimonies gathered from women of that period confirm.Footnote 58 This course of action also stripped them of the independence that the modest income could have provided.Footnote 59

Working during their youth supplemented the family income, as in the case of the young men. Those who had left their jobs could resume work in the mine, particularly when problems arose in their families. According to a text written in 1911:Footnote 60 “Many workers are daughters, sisters or wives of the miners employed in the same establishments […]. Several dozen widows of miners would be destitute”, if they were prevented from working in the mines. The high accident rate in this line of work, together with the incidence of certain occupational diseases, gave rise to situations in which women or children became the main breadwinners of mining families.

Women competed for work against adult men and especially against child labour. When the mining sector was expanding tension were less, but that changed the moment problems arose. Changes in mining are not regular but arise from various factors related to the markets and use of non-renewable resources. Difficulties recur constantly. We have analysed legislative amendments and pressure on female labour in the mines and have examined the positions of labour organizations and employers. The workplaces, however, were where the real pressure existed. Here, women must have had to prove their value, earning their place in the activities carried out in the mines. This was particularly significant in the basins, where the percentage of women workers was significant. This resistance is noticeable in the employment figures. We have indicated that the overall percentage of women declined in the basin of Asturias. Dividing the figures by age segments, however, reveals that the decline occurred among those under eighteen, while the percentage of women over eighteen among total workers employed in surface tasks remained unchanged. Due to the aforementioned importance of this basin, this process significantly increased the share of women in the Spanish mining industry as a whole, from only two per cent in 1909 to over four per cent after 1917. The mining sector in Asturias continued to expand until 1918. At the end of World War I the decline set in, with the number of workers dropping from 131,615 in 1918 to 77,935 in 1933, resulting in a considerable share of job losses (over forty per cent). The problems at this time are certain to have affected the female workforce. Employment of children under eighteen decreased (Figure 7). While we might attribute this change to legislation curtailing employment of children, comparing changes in the numbers of girls and boys employed reveals a far greater reduction among girls.Footnote 61 For boys, entering the mine offered an occupational future and prospects for advancement, very different from the limited opportunities for women in this activity.

Figure 7. Percentage of women employed among total number of surface workers in the mines of Asturias, divided according to those over and under eighteen, 1902–1934.

WOMEN'S SALARIES IN THE MINES: THE LOWEST ON THE SCALE

Wages in the mines depended on a wide range of variables, such as: the skills required, the risk the tasks entailed, the cost of living, labour demand and supply, negotiating leverage, current legislation, etc. Contemporary analysts publishing social reports took for granted that gender was a variable in determining wages.Footnote 62 Wages were therefore highly diverse and are complex to reconstruct.

Data on women's wages are extremely fragmented and dispersed. Still, a national series of average daily wages among women (1908–1914) has been reconstructed based on official sources and has been compared with wages among unskilled male labourers (Table 3). The available data indicate that women's wages rose proportionately more than those recorded for unskilled male miners between 1908 and 1920 and in 1920 exceeded fifty per cent of men's wages (52.6 per cent). After 1920, the trend reversed: the wages of women stagnated, while men's wages increased until 1930. This widened the wage gap between unskilled men and women in the mines, and in 1940 wages of women averaged only 38 per cent of those earned by men.

Table 3. Evolution of average hourly wages in Spanish mining, 1908–1930 (ptas. /hour and percentage of men's salary).

Source: For 1908: Directorate General for Agriculture, Mines and Forestry (Madrid, 1911); for 1914, 1930: Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare (1931), p. LXII.

The huge gender gap in wages was not limited to the mining sector and was commonplace in the industries in Spain where women were more prevalent (garment, textile, tobacco, etc.). After 1920, the difference between women's and men's wages increased. Salaries declined across the board, and wage adjustments after World War I were considerable, particularly for women employed in mining (Table 4).

Table 4. Unskilled women's wages as a percentage of unskilled men's wages in mining and in industries where women workers were prevalent, 1914–1930 (%).

Source: Directorate General for Employment; Statistics of wages and working days corresponding to the period 1914–1930 (Madrid, 1931), pp. LII and 14.

We have used company sources to reconstruct the wage gap in some mining areas, such as the southeast of Spain, where the mines were dedicated mainly to the extraction of lead and iron (Table 5). To this end, we have examined average daily wages by general labour category (skilled labourers, unskilled labourers, and children) in the surface tasks where women were present.

Table 5. Wage gap in mining in southeast Spain. Women's wages as a percentage of men's wages 1914–1925 (%).

Source: Accounting. Wage books of the La Atlántida mine (Sierra Almagrera, Almería) 1914–1925.

Between 1914 and 1919, the overall gender wage gap narrowed, due to the favourable circumstances for Spanish mining resulting from World War I, with high wages and a strong demand for labour. After this date, wages stagnated or even dropped everywhere until 1922, due to the post-war mining crisis (coal, lead, etc.). As mentioned, women's wages declined considerably in this period, and the wage gap in mining widened until 1923. A decline in women's wages has also been observed in the agricultural sector during the same period.Footnote 63

In the coal mining industry of Asturias, where the percentage of women working in the mines was the highest in the country,Footnote 64 the wage gap was huge. During these years (1913–1921), women's wages were only 26.4 per cent of the average wage of men who worked underground, 40.3 per cent of the average wage of men who worked on the surface, 69.4 per cent of the average wage of children who worked underground, and 86.1 per cent of the average wage of children employed in surface tasks. The data (Table 6) show that the wage gap with respect to adult male wages grew continuously in the period 1913–1921. The deterioration with respect to the children's wages was not as pronounced: between 1913 and 1917 wages earned by women gradually approached those of children, but between 1918 and 1921 this trend was interrupted with respect to children working underground and stabilized with respect to those working on the surface. This situation was influenced by the severe coal mining crisis of 1920, which caused an overall wage reduction for all categories, despite the conflicts and strikes organized by the trade unions. We have estimated this reduction at around twenty per cent.

Table 6. Women's wages in the coal mines of Asturias, 1913–1921.

Source: Instituto de Reformas Sociales, Crónica acerca de los conflictos en las minas de carbón de Asturias desde diciembre de 1921 (Madrid, 1922), pp. 36–37.

In the large mining companies, women found jobs different from purely mining tasks, often providing services to miners. This is apparent in one of the largest mining companies in Spain, the Rio Tinto Mining Company, established in Huelva in 1877 and employing over 13,000 workers by the beginning of the twentieth century. These types of companies generated jobs for women in auxiliary tasks and in services offered to workers. Women were employed as nurses, hospital maids, seamstresses, cooks, kitchen assistants, cleaners, washerwomen, pharmacy assistants, etc. in the mining hospitals the company ran in Río Tinto and Huelva. Women also worked as teachers, cleaners, and cooks in the schools the company established in the area. In every branch of the company there were teams of cleaners and, from the beginning of the twentieth century, other relatively specialized occupations distributed throughout the company (telephone operators, secretaries, company store assistants, etc.).Footnote 65

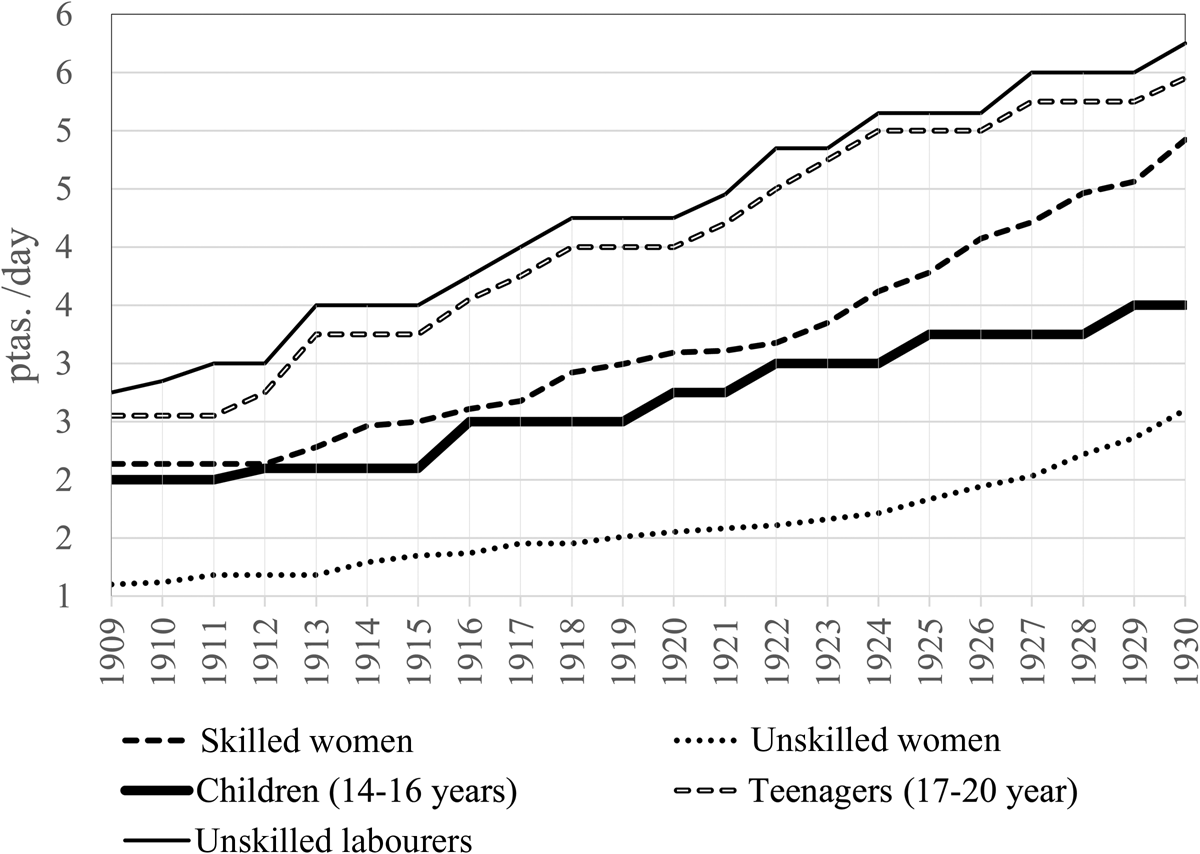

Here, skilled women (teachers, nurses, cooks, telephone operators, teaching assistants, and company store assistants) were paid less than unskilled men and even less than youths (17–20 years old). Between 1909 and 1930, the average wage gap of skilled women with respect to these categories was twenty-seven per cent and twenty-two per cent, respectively (Figure 8). The wages of unskilled women employed by the company (washerwomen, cleaners, hospital maids, station hands, etc.) were separated by a still larger gap from those of the two above-mentioned male categories. On average, between 1909 and 1930, the gap was sixty-three per cent with respect to the male labourers and sixty per cent with respect to youths.

Figure 8. Evolution of average wages of women and those of select male occupational categories in the Rio Tinto Mining Company, 1909–1930 (ptas. /day).

In all cases analysed, the wage gap between men and women in the mines was obvious and remained unchanged during the first third of the twentieth century, widening even more during periods of crisis. This gap was highly significant at the lowest occupational levels comprising unskilled male workers and even with respect to youths and children. The paltry wages of women reduced the potential income of family units, diminishing their ability to purchase basic necessities (food, clothes, housing, etc.).

THE FEMALE WORKFORCE IN MINING: CONSTRUCTION OF A LABOUR IDENTITY

We have shown that female labour in the mines represented a significant part of total employment and merits consideration in analyses of labour relations in this activity. The first question we have addressed is whether these women may be qualified as “miners”, a term that traditionally has a masculine connotation. Using the term is also controversial, as a precise definition that goes beyond the very vague description of “mine worker” is difficult to provide. Spanish miners were often uncertain about their status. In El Beal (Cartagena, Murcia), a town devoted entirely to mining, the term “miner” hardly appears in the population registry as an occupation. Instead, inhabitants report that they are “labourers”.Footnote 66 In J. Sierra,Footnote 67 we read that no mining proletariat appeared in many of the Andalusian mining areas in the golden age of Spanish mining. Somewhat differently, this remains true in the present day as well. Modern workers, who are highly skilled and use sophisticated technology, question whether they are miners. The word miner is somewhat of an entelechy.

In places where female labour was more prominent, such as in the mines of Asturias, female mine workers called themselves “carboneras” (coal women, see Figure 9).Footnote 68 This name for the female workers is consistent with those attributed to women working in other countries, such as “bal maidens” or “pit brow lasses” in the English mines.Footnote 69 In addition to the question of terminology, these women had to carve out a space in which they were accepted and acknowledged. In classifying the mineral, they became skilled at quickly recognizing the different classes of product. Footnote 70 In the Spanish Mines Report of 1911, issued by the Directorate General of Agriculture, Mines, and Mountains, the women were described as irreplaceable in these tasks, having a huge advantage over the men and boys in a job that required patience and very little muscular strength. They even asserted their worth in tasks requiring certain physical conditions.Footnote 71 A text written in 1933 reads as follows: the wagons (see Figure 6) are loaded with the mountains of mineral

using shovels, by hand. This task was usually carried out by the women and it is curious and interesting to note that their performance was much better than that of the men. The pace at which this task was usually carried out, and the physical constitution of the women, seems to be the cause of this supremacy.Footnote 72

Figure 9. Female workers in the coal mines of Asturias. First half of the twentieth century.

These texts show that the female miners of Asturias, to some degree, created their own workspace, striving to receive recognition for their work to secure their jobs.

A large part of the female workforce in the mines was directly involved in extracting minerals and suffered the problems associated with this activity: accidents, occupational diseases, etc. Many female workers suffered from silicosis, particularly those who transported the minerals.Footnote 73 As indicated by D. Bras (on female workers in Portuguese mines),Footnote 74 these women may be regarded as truly exercising the occupation of “miners”. This term includes people directly involved in extracting the underground resources.

Their objective was simply to obtain an income to support their families. Contrary to boys working in the mines, they had no prospect for promotion or specialization in the job scales. They held the lowest positions in the surface mining categories,Footnote 75 they earned far less than men (as explained in the previous section), and they had virtually no opportunity to increase their wages, as they usually worked for a fixed daily wage.Footnote 76 In any event, they did this work as a means of subsistence to cope with the different circumstances in which they may have found themselves. They were driven by the need to increase their income, which also held true in other Spanish mining basins, where serious economic problems also existed. In Asturias, however, women had greater opportunities to find work in the mines.

In this process women did not receive support from the labour associations. They did not organize in specific unions, as they did in other occupations.Footnote 77 Although they do not appear to have undertaken joint action, they maintained their status within the mining occupations. This explains why it was in Asturias that a group of women applied for the positions of mining assistants in 1984, obtaining jobs despite opposition from the unions and pressure they experienced every day in the mine. Eventually, in 1992, the Constitutional Court recognized the right of women to hold positions as mining assistants under the same conditions as men, ruling on the motion submitted by one of the female workers in Asturias.Footnote 78 This does not mean that gender equality has been achieved in the mining sector today.

CONCLUSIONS

In the second half of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century, the boom in the Spanish mining sector (the golden era) revolutionized the mining of underground resources and positioned Spain as an international mining power. This transformation required adapting forms of work organization to the new physiognomy of mining production, modern technologies, and contemporary means of production. This transformation also gave rise to a mining proletariat. The process was not uniform, giving rise to a wide range of models, some of which we have described in this paper. In this context, women had very limited employment opportunities, except in certain mining basins with a tradition (particularly in Asturias) of secondary extraction activities, subject to certain production problems that led to the endurance of family mining methods (in the case of manganese or sulphur).

As in the rest of Europe, employment of women in the Spanish mines declined during the period studied (the nineteenth century and the first third of the twentieth century). Although the number of women working in the mines increased until 1918, when their number started to decline, their share in overall employment reflected a different pattern, hovering between 3.5 per cent and four per cent until the end of the nineteenth century and then decreasing in the early decades of the twentieth century to below two per cent in the 1930s. Analysing these figures is complex, as they are based on different mining contexts, each with specific customs and evolutions.

We have shown how the State adopted labour legislation intended to limit female employment in the mines, particularly by banning women from underground work. In addition, protective legislation was enacted aimed mainly at girls and young women (under twenty-three) and at regulating leave for pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding. The fundamental objective of this legislation was to preserve the social role of women, particularly their reproductive function.

The government shared the misgivings of the mining companies with respect to the increase in unionization and disputes in the mining sector, which reached a critical point with the revolution of Asturias in 1934. Industrial paternalism therefore intensified in the first third of the twentieth century, with women playing a key role in organizing the worker households. The unions subscribed to the idea of other European labour organizations that removing women from mine work was social progress. They showed little interest in female labour in practice, preferring to use male workers.

Women who worked in the mines obtained a means of subsistence, not only to supplement the family income but often as a principal source of income in an activity known for high death and accident rates. The problem was that such employment was difficult to access. In places where there was some tradition of female workers, women could cope with the pressures and the above-mentioned changes in work organization, carving out a space where they could prove their abilities. This was particularly prevalent in Asturias, where, at this time, women occupied their own space in selecting and loading minerals (tasks that also used female labour in other countries). In this way, they attained a certain status in the mines in some basins.