In 1923, in the British colony of Trinidad, a young English woman returned from visiting her family in a suburb of the capital, Port of Spain, to find that her Chinese husband of six years, Lý Li![]() u, had packed up his possessions and left her and their two small children.Footnote

1

A Chinese trader, originally from Hong Kong, Lý had been working at a Chinese import/export company when this woman met and married him.Footnote

2

Now, without warning or explanation, he had vanished, presumably to return to Hong Kong. Indeed, he never returned to Trinidad or saw her, or their children, again. In his later reminiscences, Lý did not refer to his wife or children by name, but conveyed his terrible guilt at having abandoned them. In a less predictable regret, Lý expressed sadness that his wife would forever assume he was racially Chinese and would never know his real race and identity.Footnote

3

For, despite his appearance, his fluency in Cantonese, his position at a Chinese company, and his years spent in Hong Kong, he was not the overseas Chinese businessman he pretended to be. In fact, he was an escaped Vietnamese political prisoner from the notoriously harsh penal colony of French Guiana, about seventeen days away from Port of Spain by boat.

u, had packed up his possessions and left her and their two small children.Footnote

1

A Chinese trader, originally from Hong Kong, Lý had been working at a Chinese import/export company when this woman met and married him.Footnote

2

Now, without warning or explanation, he had vanished, presumably to return to Hong Kong. Indeed, he never returned to Trinidad or saw her, or their children, again. In his later reminiscences, Lý did not refer to his wife or children by name, but conveyed his terrible guilt at having abandoned them. In a less predictable regret, Lý expressed sadness that his wife would forever assume he was racially Chinese and would never know his real race and identity.Footnote

3

For, despite his appearance, his fluency in Cantonese, his position at a Chinese company, and his years spent in Hong Kong, he was not the overseas Chinese businessman he pretended to be. In fact, he was an escaped Vietnamese political prisoner from the notoriously harsh penal colony of French Guiana, about seventeen days away from Port of Spain by boat.

Such a story goes against the stereotype of the penal colony of French Guiana, usually positioned as a hellish prison from which escape was nigh on impossible. Its horrific reputation was encapsulated by its name among prisoners, and eventually the general public: the guillotine sèche, the “dry guillotine”, as it killed slowly, but just as surely, as a guillotine.Footnote 4 Films like Papillon (1973) depict the extraordinary lengths to which prisoners had to go to escape; impersonating a Chinese businessman was not one of them.Footnote 5 The apparent ease with which Lý and his compatriots escaped from the supposedly secure penal colony of French Guiana to sail to Trinidad is striking. And they were not alone; their stories trace threads of “punitive mobility” that are not reflected at all in the colonial archival record.Footnote 6

To understand how these exiles and subsequent groups of Vietnamese prisoners engineered their escapes, and reclaimed agency in their transportation, it is necessary to explore the skills they learned while circulating within a cosmopolitan East Asian world. A world they inhabited at the beginning of the twentieth century as they sought expertise, which they strategically applied to the predicament of exile and imprisonment. Narrating their histories is undoubtedly a perspective from the colonies, one that is about the unique world – and resources – of East Asian convicts in the colonial French empire. However, it also shows the societal and penal layers of French Guiana refracted through a different lens, which is not just from the colonial perspective or using the sources of the archival apparatus of the colonial power to mould the historical narrative. Examining the lives of these exiles reveals that the ability of the colonial state to act as a surveillance apparatus was often far more limited than imagined. French authorities were often unable to police boundaries between prisoners from Indochina and the resident Chinese communities in the penal sites. Many Vietnamese prisoners came from an ethnically Chinese background, or a culturally Chinese world, and the sites to which they were exiled (even the penal colonies themselves) contained diasporic Chinese communities. For many prisoners, knowing Chinese was their greatest asset or being able to “pass” as Chinese the most valuable tool to facilitate escape. Arguably, for many of these prisoners, the ethnoscapes of their exile were not as unfamiliar a world as the French authorities had intended. As well as being within a penal context, they were within the cultural and linguistic milieu of the Chinese diaspora – a diaspora that traversed both French and British colonial boundaries.

Colonial scholarship concerned with colonial projects has largely focused on connections between the metropole and the colonies as opposed to intercolony exchange. This article seeks to make connections from Indochina within a wider world of transcolonial constraint and mobility. Some connections were new, while others have historical roots. In this case, the historic flows and circulations between southern China and Vietnam were transposed to a new – Caribbean – context. Therefore, this article moves beyond notions of imperial centre and colonial penal periphery by examining South–South connections and by examining these prisoners’ lives beyond the stream of scholarship on colonial institutions of incarceration. Exploring their exilic trajectory from their perspective, and not through a colonial lens, tells an entirely different historical story; one that does not end in French Guiana with one-page prisoner dossiers, but instead with a historical narrative that indicates “expressing choice and identity in the most unpromising of penal circumstances”.Footnote 7

A caveat: undeniably, these prisoners’ stories are not the stories of all prisoners within the often brutal penal colony of French Guiana. Many prisoners – Indochinese or other – experienced aspects of the violence and despair of the “dry guillotine” just as the memoirs described. As the Introduction to this special issue indicates, “to speak of punitive sites as ‘contact zones’ is not to downplay the brutality of convict labour regimes”.Footnote 8 However, the penal colony was not monolithic. Different sites of imprisonment, different racial backgrounds, and different temporal periods of confinement all reveal the diversity of punishment, captivity, and agency within one penal colony and its various penal sites. To be able to trace these threads, it is necessary to look at this historical narrative from the Vietnamese perspective.

The society for the encouragement of learning

The leafy campus of St Joseph’s College, an elite Catholic secondary school in Hong Kong, founded in 1875 and still enrolling students today, seems an unlikely place for a meeting that ultimately led to Lý Liễu’s double life in Trinidad. Lý was sent there in 1905 at the age of twelve, his forward-looking father determined that Lý should benefit from a cosmopolitan education. Vietnam’s colonized status was greatly resented by many Vietnamese, who sought wider East Asian milieus – especially Hong Kong and Yokohama in Japan – in which to organize anti-colonial activities. For Vietnam, a shared intellectual history with China meant that locations in southern China were the logical sites of such interactions. Indeed, it was at St Joseph’s College that Lý met anti-French activists, and by the time he was fifteen he had joined a group with the innocuous name of “Khuyến Du Học Hội” (“The Society for the Encouragement of Learning”), hereafter KDHH.Footnote 9 After leaving St Joseph’s College, Lý studied at a Centre for English Studies in Hong Kong, while helping students clandestinely arriving from Vietnam and assisting with the broader anti-colonial effort directed by Vietnamese nationalists in various South East- and East Asian countries.

Another key member of the KDHH was Nguy![]() n Quang Diêu, who was born, in 1880, in a small village in Sa Đéc province, southern Vietnam, into a family of Confucian scholars.Footnote

10

As was customary, Diêu began his studies of the Confucian classics at the age of six, and by ten he was known locally as a skilled writer.Footnote

11

A glorious future in the Vietnamese civil service beckoned throughout his teenage years. However, Diêu eventually decided to break off studying the texts of the Vietnamese examination system, “apparently having concluded that clandestine fund-raising, recruitment, and distribution of propaganda held more possibility of saving his country than the most conscientious, sophisticated interpretation of the [Chinese] classics”.Footnote

12

n Quang Diêu, who was born, in 1880, in a small village in Sa Đéc province, southern Vietnam, into a family of Confucian scholars.Footnote

10

As was customary, Diêu began his studies of the Confucian classics at the age of six, and by ten he was known locally as a skilled writer.Footnote

11

A glorious future in the Vietnamese civil service beckoned throughout his teenage years. However, Diêu eventually decided to break off studying the texts of the Vietnamese examination system, “apparently having concluded that clandestine fund-raising, recruitment, and distribution of propaganda held more possibility of saving his country than the most conscientious, sophisticated interpretation of the [Chinese] classics”.Footnote

12

Members of the KDHH spent their time travelling between Indochina and southern China (including Hong Kong) to circulate money and publications. However, these East Asian activities came to an end on 16 June 1913, when British authorities in Hong Kong received a tip-off and Diêu and his colleagues were arrested at a supporter’s house. The Consul of Hong Kong, Gaston Liebert, briefly mentioned their arrest in his private papers: “[S]ix Annamites have been arrested by the English police in Hong Kong where they went to make bombs. Ba Liễu, or Lý Liễu, a former student at St Joseph’s school in Hong Kong, was one of them”.Footnote 13 Some reports indicated that bomb-making equipment was discovered in the house, which may be factual given British reticence to arrest Vietnamese without material evidence of criminal involvement.Footnote 14

Deportation to French Indochina followed and a criminal tribunal in Hanoi subsequently sentenced four of the group on 5 September 1913.Footnote 15 Only one deportation dossier still exists in the French colonial archives, for a member of the Society called Đinh Hữu Thật, citing his crime as “criminal association”.Footnote 16 Such lack of documentation makes it difficult to determine why the length of their sentences varied dramatically: all were deported to French Guiana, but the sentences ranged from perpetual labour to five years (which was Lý’s short sentence, perhaps on account of his youth?). However, they were all sentenced to relégation, i.e. following the completion of their sentences, under the law of relégation, they had to remain in French Guiana for the rest of their lives. Issuance of the sentences in 1913 meant the group was exiled just before the advent of World War I disrupted overseas deportation.Footnote 17

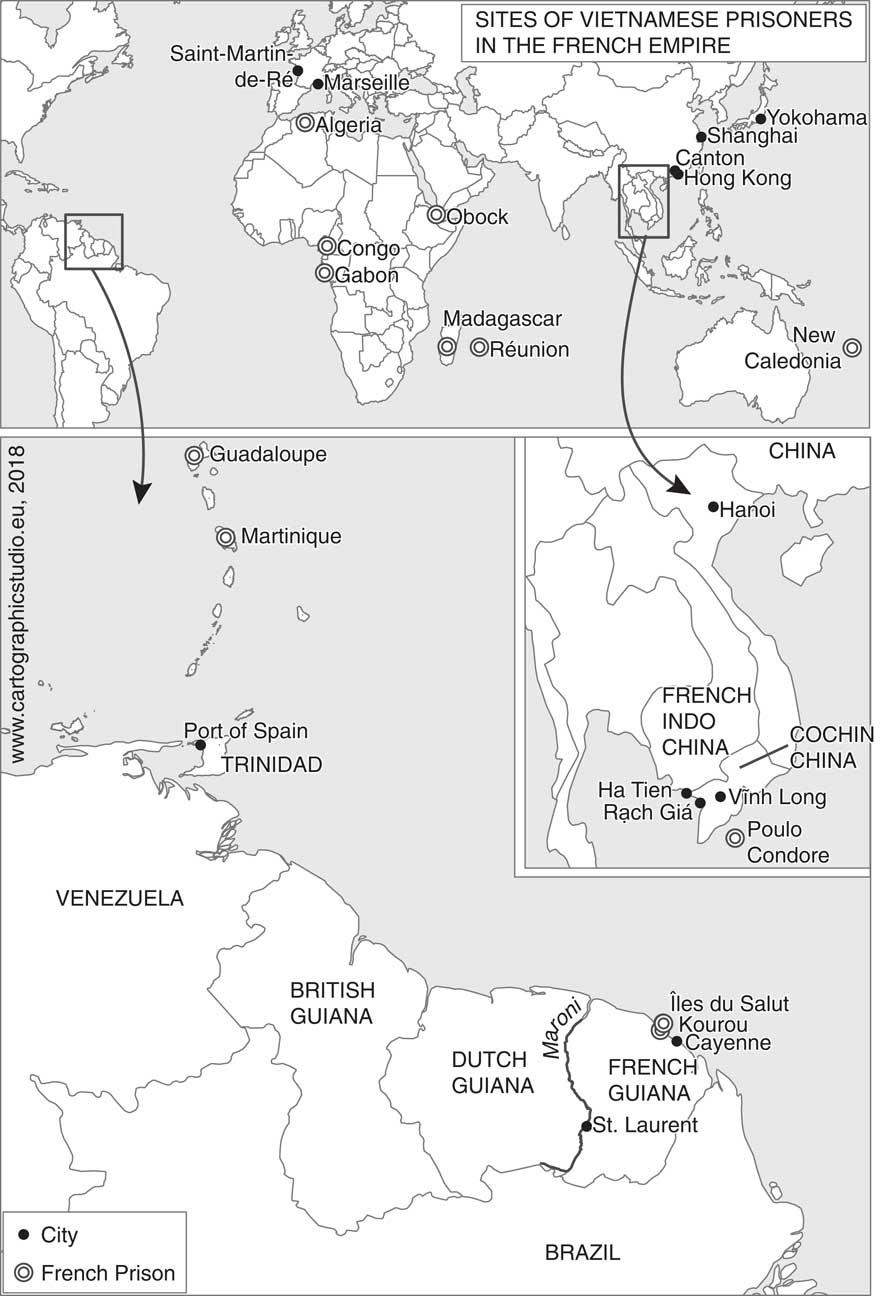

Figure 1 Sites of Vietnamese prisoners in the French empire.

Transportation, race, and labour

Nguy![]() n Quang Diêu and Lý Liễu joined the stream of prisoners – both common-law and political – who travelled from French Indochina to various points throughout the French empire. Throughout the ninety-year French colonization of Indochina (1863–1954), approximately 8,000 prisoners – many of them convicted of political crimes – were exiled to twelve different geographical locations. From Gabon to Guiana, there was hardly a corner of the French empire to which they were not sent. However, the exile location mostly depended on the category (and context) of the prisoner in question. Some prisoners required special surveillance (or, more rarely, special privilege). Different locales accepted different kinds of prisoners at different times. Sometimes, French territories submitted requests for hard labour convicts for specific colonial projects and their requests may or may not have been granted. At different periods, prisoners from Indochina could be sent to the following exilic locales: Gabon, Congo (both incorporated into French Equatorial Africa in 1910), Obock (later part of French Somaliland), French Guiana, New Caledonia, Madagascar, Réunion, Martinique, Guadeloupe, Algeria, and French Oceania (both Tahiti and the Marquesas). Some locations – Algeria, Tahiti, and the Marquesas – were used only for elite political prisoners. Indeed, there were three key categories of prisoner: exiles, deported prisoners (political motivation), and transported prisoners (common-law prisoners). However, the categories blurred and overlapped in many ways. Prisoners were sent from Indochina for a variety of reasons, from serious criminal crimes like murder to suspected sedition against the colonial authorities. Confusion applied to the world of deportation and exile; those accused of political crimes and common criminals, forçats, were often placed in the same convoys and had similar fates. In that sense, being transported and being exiled were often synonymous, even if the terminology used was slightly different. Exiles required an exile decree, which had to stipulate the grounds for exile; additionally, a tribunal or trial might take place, but the decree was sufficient. Deportation came through the established French court or, as in September 1913, a specially convened criminal commission.

n Quang Diêu and Lý Liễu joined the stream of prisoners – both common-law and political – who travelled from French Indochina to various points throughout the French empire. Throughout the ninety-year French colonization of Indochina (1863–1954), approximately 8,000 prisoners – many of them convicted of political crimes – were exiled to twelve different geographical locations. From Gabon to Guiana, there was hardly a corner of the French empire to which they were not sent. However, the exile location mostly depended on the category (and context) of the prisoner in question. Some prisoners required special surveillance (or, more rarely, special privilege). Different locales accepted different kinds of prisoners at different times. Sometimes, French territories submitted requests for hard labour convicts for specific colonial projects and their requests may or may not have been granted. At different periods, prisoners from Indochina could be sent to the following exilic locales: Gabon, Congo (both incorporated into French Equatorial Africa in 1910), Obock (later part of French Somaliland), French Guiana, New Caledonia, Madagascar, Réunion, Martinique, Guadeloupe, Algeria, and French Oceania (both Tahiti and the Marquesas). Some locations – Algeria, Tahiti, and the Marquesas – were used only for elite political prisoners. Indeed, there were three key categories of prisoner: exiles, deported prisoners (political motivation), and transported prisoners (common-law prisoners). However, the categories blurred and overlapped in many ways. Prisoners were sent from Indochina for a variety of reasons, from serious criminal crimes like murder to suspected sedition against the colonial authorities. Confusion applied to the world of deportation and exile; those accused of political crimes and common criminals, forçats, were often placed in the same convoys and had similar fates. In that sense, being transported and being exiled were often synonymous, even if the terminology used was slightly different. Exiles required an exile decree, which had to stipulate the grounds for exile; additionally, a tribunal or trial might take place, but the decree was sufficient. Deportation came through the established French court or, as in September 1913, a specially convened criminal commission.

French Guiana was the most common destination for prisoners from Indochina as they were considered constitutionally better equipped to withstand tropical diseases.Footnote 18 Although exposure to malaria in the climates of Indochina could certainly assist in building up immunity, yellow fever was initially the most virulent (and often fatal) disease in French Guiana.

Situated on the northern coast of South America, French Guiana was established as a French settler colony in 1852.Footnote 19 One reason for its selection as a site for penal settlements was the hope that this new role would stimulate its development after a disastrous French settlement had been attempted at Kourou. Prisoners seemed the next logical step. There was a desire to punish and a desire to reform and to re-socialize criminals so as to reinsert them into civil society. Out of this unresolved dichotomy evolved provisions for the transportation of certain categories of criminal to French Guiana in 1852 (two years before an 1854 law officially created the bagne there) and then to New Caledonia. Although the intention was to punish the criminals, it was also assumed that they would be regenerated by life and work in a far-off rural environment, that their work would contribute strongly to the colony, and that the recidivist would be an agent in the service of France’s larger colonial project.Footnote 20

However, yellow fever meant French Guiana was an extremely difficult place in which to thrive, although the reason for the fever’s prevalence was not understood until the end of the nineteenth century.Footnote 21 Malaria also posed a big problem. Mortality rates were high, and in the first years of the penal colony between 1852 and 1866 close to forty per cent of all the convicts died.Footnote 22 In 1867, the government prohibited the transportation of French citizens to French Guiana. Only “African and Arab prisoners whose constitutions are resistant to the climate of the colony should be sent”.Footnote 23 New Caledonia was used instead for French prisoners until 1897, when there was some metropolitan debate that it had become too comfortable an exilic locale and French prisoners were again sent to French Guiana. Overall, 70,000 prisoners were sent to French Guiana and it operated as a penal colony until 1952, with the last convicts arriving from France in 1937.

Journey to the jungle

Whether classified as political or common-law, prisoners from French Indochina were transported to French Guiana under similar conditions. The Society for the Encouragement of Learning group did not go directly to Cayenne, French Guiana’s main town, but via Marseille and St Martin de Ré.Footnote 24 From his two-week stay in a prison in Marseille, Diêu described the French city as an attractive port, organized in a very “civilized” way, rendering French treatment of colonized people even more perplexing. A poem Diêu claimed to have composed in Marseille refers to the fact that he found the justifications for his imprisonment opaque:

Heaven and earth give birth to us to have will

Not knowing at all what crime I have committed

Resign oneself without understanding

How is this the law of civilization?Footnote 25

From Marseille, the prisoners were sent to St Martin de Ré off La Rochelle in northern France, to await a biannual sailing. On the boat, they were locked into cages holding sixty to eighty people each, and made the journey in fifteen to twenty days, depending on whether the ship, the transportation vessel the Martinière, stopped in Algeria. In a later account, Lương Duyên Hồi, a Vietnamese prisoner, described the conditions on the Martinière. “The ocean waves were very high and many Vietnamese people on the boat were seasick”.Footnote 26 Unaccustomed to such rough seas, it was vital to remain vigilant for people falling unconscious from seasickness.Footnote 27 Tensions on board could be exacerbated by the length of the exiles’ sentences. For example, in 1890, a convoy of 133 deportees from Indochina contained eighty prisoners sentenced to perpetual exile, which added to their “anxiety and tendency to disrupt”.Footnote 28 The Martinère deposited the prisoners on the Maroni River near Dutch Guiana. The largest prison camps in French Guiana, St Laurent and St Jean, were located near the Maroni River.

The convict population of French Guiana ranged between 3,000 and 7,000 prisoners; despite the arrival of some 700 new arrivals per year, deaths and attempted escapes kept the number of prisoners relatively constant.Footnote 29 Following their arrival, French convicts were sorted by sentence category and then given work assignments accordingly. The convicts were almost all male; the high mortality among French women meant that their transportation ended in 1906.Footnote 30 Few women from Indochina were transported. Only ten Vietnamese women are recorded out of the 3,185 female dossiers extant in the archive, with no female Cambodians or Laotians listed.Footnote 31

Those designated as “recalcitrant” were assigned to cut down trees in the rainforest or sent to the Iles du Salut. Even here, a hierarchy emerged among the islands – on the Ile Royale, convicts were left relatively alone; those who attempted escape were sent to solitary confinement on the Ile du Diable [Devil’s Island] was reserved primarily for European convicts – however, conditions there were generally better than on the Ile du Diable.Footnote 32 In addition to these were the main camp at St Laurent, the notorious disciplinary camp of Charvin, and Camp Hatte, to which disabled prisoners were sent. Only the best-behaved convicts were allowed in Cayenne.

In 1890, the Governor-General of French Guiana assured the Minister of Colonies that political prisoners from Indochina were immediately separated and given tasks commensurate with their sentences, but this assertion does not reflect other archival and anecdotal sources.Footnote 33 Prisoners from Indochina almost always occupied one of three roles: domestic servant, agricultural worker, or fisherman. Indeed, the stereotype that Indochinese (especially Vietnamese) were diligent workers sometimes assisted them in getting lighter, less guarded, tasks. For example, Cambodians were often put into domestic agricultural work, including attempts at rice cultivation, considered less arduous than clearing forests.Footnote 34 Throughout the 1890s, Vietnamese convicts were allowed to build “Vietnamese-style” houses and had a virtual monopoly over fishing; catches were presumably used to supplement the meagre fare of the guards.Footnote 35 On the Laussant Canal, which ran through Cayenne, it was reported that “the Vietnamese have formed a veritable village, where they help people with illnesses which are dealt with within the community”.Footnote 36

The harbour of cayenne

For so long I’ve waited to see Cai Danh

As I glance upon the scenery, I am emotionally stirred.

The broad, vast sea courses with azure,

While green forests mist over the land.Footnote 37

The landscape Diêu described in this poem – the scenery of “Cai Danh” – was not a port on the waterways of the Mekong Delta in southern Vietnam where he grew up, but rather the harbour of Cayenne. The emotions roused come at the end of an arduous voyage during which many of his fellow prisoners suffered terrible seasickness and “crossing the ocean for those unaccustomed to sea travel made them feel ill, especially at his advanced age”.Footnote 38

Diêu wrote the poem in a traditional Vietnamese poetic form: the luật thi, consisting of eight even syllable lines. As historian George Dutton points out: “The best-known poems in this [poetic] form were those produced by court officials who travelled to China on embassies to the Chinese court, poems that commented most frequently on the scenery but also on events of the journey”.Footnote 39 By rendering the unfamiliar into this familiar poetic scheme, Diêu laid claim to the landscape of French Guiana. He made legible to his (eventual) audience back in Vietnam this foreign topography.Footnote 40 By creating a literary connection from exilic locale to homeland, Diêu was creating a punitive cultural circuit along which his eventual readers could travel.

Although the opening of the poem is framed by traditional Vietnamese poetic tropes, as it progresses it betrays more modern anxieties about the position of the Vietnamese in a world where countries have ceased to exist. After the opening lines, Diêu continues:

But barbaric catastrophes befall these people;

How much misery shall my own stock endure?

Extinction is mirrored glaringly before my eyes,

Witnessing the race, I shudder to think!Footnote 41

The indigenous inhabitants of French Guiana are evoked in the penultimate lines as facing extinction. The use of the word chủng, “race”, suggests Diêu was referring to the race inhabiting this “catastrophic” place: the Amerindians, indigenous inhabitants of French Guiana, rather than the annihilation of the penal colony detainees.Footnote 42 The intricacies of a racially mixed Caribbean society were almost certainly lost on him. That Diêu refracted this landscape through a lens of Social Darwinism and fears of racial extinction is not surprising.Footnote 43

Although Diêu later claimed to have penned this poem when he first saw the harbour of French Guiana, this is poetic licence. Supposedly moved to write by the scenery itself, he creates an allusion of the emotional moment of arrival and of horror. However, as mentioned above, convict ships arriving from St Martin de Ré did not dock at the harbour of Cayenne; they sailed to St Laurent du Maroni in western French Guiana, which was the main processing centre for prisoners arriving at the penal colony. It is also unlikely that Diêu saw any Amerindians at the harbour of St Laurent du Maroni; the arrival of the French had pushed them further and further inland.

Dense jungle toil

When they arrived in French Guiana, the group of four was assigned to a work unit to cut wood in an inland region, and Lý was placed as a guard in charge of his fellow prisoners. Putting Vietnamese prisoners in charge of other Vietnamese prisoners was also a feature of the prison system in Indochina, where so-called caplans, who were half-prisoner and half-guard, occupied this role.Footnote 44 Convicts at work were not accompanied by guards. What is striking here is borne out in other writings on the bagne, which is simply that the penal colony of French Guiana was understaffed. In Beyond Papillon, historian Stephen Toth argues that “physical violence and punishment of the body was ever present” in French Guiana.Footnote 45 He also argues that the penal colony was severely lacking in personnel.Footnote 46 Contradictions abound. Physical punishment was undoubtedly part of the regime of the penal colony, but its omission from the recollections of the KDHH is striking. As is the absence of the guards, and their sadism, which figured so predominantly in French memoirs.Footnote 47 There are two ways to think about this: firstly, that Diêu and Lý wanted to represent themselves as more autonomous and with greater agency than was actually the case. Secondly, that they were essentially left unguarded on the premise that escape was impossible and, as mentioned before, the number of guards was insufficient.Footnote 48 The idea of spreading out convicts to labour in small work crews also meant it was difficult to guard them.Footnote 49

Due to his caplan position, Lý could slip away from the camp and was able to go to Cayenne at night to mix with the Chinese community. His many years of education in Hong Kong meant that, even though he was the youngest member of the four, Lý spoke English, Cantonese, and French fluently. His Cantonese came in especially useful; he was able to get medicine, non-prison clothing, and send and receive letters clandestinely.Footnote 50 Convicts were dressed in distinctive grey clothing that made escape harder; medicine was also vitally important because of the rampant diseases of the penal colony.

These affinities with the Chinese world meant that the landscape of the penal colony had a different cultural legibility to him than to most of the inmates. In colonial Cayenne, indeed throughout French Guiana, Chinese trading communities (many Cantonese-speaking) were intimately woven into the fabric of penal colony society. Most had migrated from Shanghai and Canton, and as “commercial possibilities such as running a small store failed to attract many Creoles, it opened the way for Chinese domination of the small-scale retail market”.Footnote 51 Indeed, the term “Le Chinois” came to mean “corner market” in Guyanese French. Chinese were renowned for selling everything from “champagne to sun-helmets”.Footnote 52 Anecdotal accounts from both prisoners and visitors to the penal colony indicate that Chinese traders throughout French Guiana acted as conduits for the sending of (unauthorized) correspondence, and not just for Vietnamese prisoners.Footnote 53 Although an anecdotal observation, one visitor noted that “it is surprising what knowledge these Chinese possess of certain convicts, through acting as the medium by which letters are sent and received. Often they know more about the men than the authorities”.Footnote 54 Lý claimed he mingled with this Chinese community on almost nightly visits.

Meeting a young Cantonese speaker, educated at the prestigious St Joseph’s College of Hong Kong, must have been an unexpected encounter to these Chinese, many of whom had emigrated from areas with which Lý was very familiar. Diêu also portrayed the exiles as being connected to global events through Lý’s contacts in Cayenne, who told him of the progress of World War I and the exile to Réunion of the former Vietnamese Emperor Thành Thái and his son Emperor Duy Tan. The news of these other exiles inspired them, raising hopes that the need to exile the emperor indicated France’s weakened condition.Footnote 55 On the premise that France’s position in Indochina was compromised due to its involvement in the war, it seemed an opportune moment to attempt escape.Footnote 56

Tafia dreams of escape

Anecdotal accounts indicate that prisoners in French Guiana had two fixations to help them endure the penal colony: “tafia [cheap homebrewed rum] and the hope of escape”.Footnote 57 Anthropologists, social scientists, and historians may differ in their opinions about aspects of the penal system in French Guiana; however, there is one fact on which they all agree: escape was difficult and dangerous. Anthropologist Peter Redfield estimates non-returned escapees at between two and three per cent of the prison population, but it is impossible to know how many made it to a safe locale.Footnote 58 Historian Stephen Toth simply states: “To flee was a truly remarkable feat.”Footnote 59 Or, to be more precise, to flee successfully was a truly remarkable feat. Even if the guard system was understaffed there were “two constantly watching guards who are always at their post: the jungle and the sea”.Footnote 60 French Guiana for the most part operated as a prison without walls in which the lack of money, travel documents, non-prison clothing, and access to a seaworthy boat or raft all precluded escape. Even if acquiring the necessities for escape was possible, trusting both your co-conspirators and a boat captain (if involved) was vital.Footnote 61 Maps of South America carried a huge premium. Lack of geographical knowledge made many prisoners dependent on prison rumour to understand the surrounding terrains.Footnote 62 Lý had access to many necessities, including maps, through his Chinese contacts in Cayenne.Footnote 63

Several possible escape routes existed and “the most common was to head northeast into what was then Dutch Guiana, either through the jungle or floating on a raft”.Footnote 64 However, escaped prisoners carried a one-hundred-franc capture award, an inducement for Amerindians living in the area.Footnote 65 To reach Brazil, British Guiana, Venezuela, or Trinidad was even harder.Footnote 66 Often, attempts to reach Trinidad ended in death – the sea could be rough and difficult to negotiate without skilled nautical expertise – or in extradition. In 1931, a law was passed in Trinidad to stop escapee extraditions to French Guiana because of British concern over conditions in the penal colony, but that was comparatively late for most prisoners.Footnote 67 An unsuccessful escape meant solitary confinement for a period of time, and between two and five additional years of forced labour added to the original sentence. This penalty increased over time as more prisoners attempted to escape.Footnote 68

It could be argued that it was not altruism, a fictive sense of kinship, or racial solidarity that motivated the Chinese in Cayenne to assist Lý and his friends in their escape. Rather, there was recognition that members of the KDHH had both linguistic and business acumen, marketable commodities in the transcolonial South American/Caribbean world. The prisoners were all literate in Chinese, Lý was fluent in English, and they participated in commercial enterprises to raise funds for the KDHH. They were potentially valuable assets among overseas Chinese networks. On the other hand, the Chinese in Cayenne who facilitated their escape from French Guiana did not benefit directly from their escape in terms of either labour or skill. Instead, these Chinese residents jeopardized their permission to live and work in French Guiana. Acting as a postal service for prisoners was certainly unauthorized, but a blind eye could be turned; facilitating the flight of hard-labour political deportees was definitely a different level of assistance.

Aiding prisoners to escape would have elicited severe repercussions from the prison authorities. A sense of affinity to the group, perhaps especially to Lý due to his many years in Hong Kong, may have induced them to assist; it was rare for the Chinese communities to assist in helping so-called bagnards (penal colony convicts) escape. As one memoir mentions, some Chinese near the river in St Laurent du Maroni would undertake to arrange escapes in return for a suitable bribe, but such an arrangement was expensive.Footnote 69 Indeed, there were groups better known for providing this kind of assistance – e.g. Brazilian ship captains and crew.

Two differing accounts have the group leaving for Trinidad in a “native” fishing boat as well as a Chinese-owned boat. However, in both accounts they were disguised as members of the Chinese community in Cayenne, with their passage paid for by that community.Footnote 70 For the members of the KDHH, racial masquerading was a skill perfected in their years travelling between China and Vietnam. As for the British authorities in Trinidad, one Asian looked pretty much like the next. Probably because of its small population and relative underdevelopment, Trinidad offered greater economic opportunities to ex-indentured Chinese, and about 3,000 Chinese left French Guiana and relocated there in the 1870s and 1880s.Footnote 71 In Trinidad itself, the Chinese had moved off the plantations and into trade as early as the 1870s.Footnote 72 This meant there were strong connections between Chinese communities in Trinidad and French Guiana, and may explain why the Chinese in Cayenne were able to facilitate contacts in Port of Spain. Many Chinese Christians had converted in the West Indies or elsewhere prior to coming to Trinidad.Footnote 73 This impacted how they were viewed within the colonial hierarchy as they were assessed positively in contrast to the Indians or Africans.Footnote 74 Therefore, relations between the Chinese community and the British authorities were generally good and the addition of a few more Chinese members to their ranks would not have elicited comment. Indeed, Diêu mentioned that the group knew very little about this English tobacco island called “Tri-li-ni-dich” island, except that there was a large Chinese community there. The Chinese contacts who facilitated their escape gave the men letters of introduction to Chinese businesses in Port of Spain, Trinidad. It is unclear how much these Chinese employers in Port of Spain knew of the background of their new employees. An 1886 ordinance meant that all those suspected of being escapees from French Guiana were meticulously photographed, fingerprinted, and their physical appearance documented in detail by British authorities.Footnote 75 Their details were then sent to the French authorities in Cayenne for verification. Several of the prisoners picked up were still in prison uniform or clearly had no travel documents, problems that this group did not encounter.Footnote 76 It is undoubtedly true that dishevelled white men were more identifiable as escapees from the penal colony than “Chinese” travellers among a group of Chinese traders.

Once they arrived in Port of Spain, the men worked “undercover” of being Chinese in different Chinese companies. Diêu worked for an Anglo-Chinese commercial firm. Lý married the unnamed English woman he met through the Chinese business that employed him – an interracial marriage facilitated by his fluency in English. The fact that his wife never realized he was Vietnamese, or an escapee from French Guiana, may demonstrate that his true identity did not circulate within his Chinese firm in Port of Spain. Given Trinidad’s extradition policies, discretion was essential and Lý took that discretion even into the matrimonial home. After Lý married, he was able to borrow money from his wife’s family and set up a small store, which he and his wife ran together.Footnote 77

In his recollections, Lý discussed how, on the day he left, when his wife and children were visiting her parents, he removed some of their joint savings to assist with his passage from Port of Spain. “He was not able to speak one sentence to say goodbye, but left and was separated from her forever.”Footnote 78 The Chinese community in Port of Spain raised funds to facilitate four passages, which the group supplemented from their savings.Footnote 79 They left Trinidad in 1920 or 1921 and spent the next few years in various locations in southern China.

Little is known of Lý’s precise activities over the next few years based in southern China and Hong Kong. However, in 1929, Lý decided to return to Vietnam. Ironically, this ultimately led to his rearrest in the city of Vinh Long in southern Vietnam four years later. In 1933, a colonial tribunal found him guilty of fomenting rebellion and sentenced him to fifteen years’ hard labour on the prison island of Poulo Condore (off the southern coast of Vietnam). Established in 1861, prior to the consolidation of French Indochina, Poulo Condore was a notorious penal site for prisoners from all the territories of French Indochina. As historian Peter Zinoman points out, “[T]he intensity of the Vietnamese resistance [against the French] generated demands for fortified camps where anticolonial leaders and prisoners of war could be locked away”.Footnote 80 That fortified place was Poulo Condore, where thousands of Vietnamese prisoners died during the colonial period. Lý died there, shortly after his sentencing, at the age of forty.

Although Diêu claimed that, in 1921, he returned to China and Vietnam via the United States and visited Washington DC, there is no evidence to corroborate that this was indeed the route taken.Footnote 81 When Diêu reached Canton he met up with many members of the exiled Vietnamese community and wrote a pamphlet, Việt Nam cách mạng lưu vong chư nhân vật [Vietnamese Revolutionary Exiles] in Chinese.Footnote 82 On his return to Vietnam, he published poetry and political treatises, which circulated widely in the Mekong Delta at the end of the 1920s.Footnote 83 Diêu was never rearrested.

Lý Liễu and his colleagues were not the only Vietnamese group to escape French Guiana through Chinese contacts. Between 1907 and 1924, another thirteen members of groups attached to “new learning” groups escaped from French Guiana to Trinidad with Chinese assistance. Ironically, the four members of the KDHH may have passed by these other Vietnamese escapees from French Guiana in the streets of Port of Spain unaware of their racial origins, or entertaining suspicions but not wanting to draw attention to themselves.Footnote 84 Not as much is known about the members of these other groups, except for information from the grandson of one of the escapees, Đỗ Văn Phong.Footnote 85 No year of escape was narrated to his family, just that in Trinidad “a number of Chinese people protected him”.Footnote 86 However, it was prior to 1924 because it was then that his family got news of his escape to Port of Spain, where he pretended to be a practitioner in Chinese herbal medicine after establishing a small business.Footnote 87 Đỗ eventually returned safely to Vietnam and became a successful publisher.

Perhaps from the perspective of a Western historian, Lý Liễu’s decision to return to Hong Kong, and eventually Vietnam, marked a tragic turn in his tale that ended in his untimely death in Poulo Condore. However, for the only Vietnamese historian who has written about Lý Liễu, the real tragedy is Lý’s endlessly restless spirit. The fact that his half-English, half-Vietnamese children in Trinidad were unable to place a grave in his natal village means a spirit who will never be at peace and who will ceaselessly haunt the penal vestiges of Poulo Condore.Footnote 88 There is no marker of his grave, no artefact connecting him to his natal village, a different kind of “marker” than Western historians seek.

Narratives of prisoners within French penal flows can often be reconstructed from the extensive extant archives at the Centre des Archives d’Outre Mer in Aix en Provence. Lý Liễu’s is not one of them. He makes only three very brief appearances in an official archive. He appears at the times of sentencing – 1913 and 1933 – and he appears briefly in the private papers of Gaston Liebert, the French consul in Hong Kong at the time of his arrest. Although there are voluminous files in the French archives on French Guiana, Lý Liễu’s story also shows the lacunae of the archives and the need to read widely in different contexts in order to piece together a multinational narrative of a very cosmopolitan prisoner. Traces of his life had to be carefully reconstructed from historical strands and in Vietnamese and Chinese texts so that his hidden life, one far from the eye of colonial surveillance, could be told. Lý Liễu’s life history illustrates the necessity of going beyond the apparatus of the archive to explore penal circulations and connections not readily apparent, and the vital importance of transcending national and/or colonial textual and archival boundaries to examine both the constraints on, and mobility of the lives of, transcolonial exiles.