The concept of “direct action” became prominent over the last decade of the nineteenth century and the first decade of the twentieth century. Its rise signalled much more than the prevalence of a new descriptive term, for the concept quickly became a central axis of identification. Direct action served as the title of new pamphlets and journals and as a declared commitment of new political and industrial associations. Its deployment signalled the self-conscious awareness of a new political presence.

The transnational emergence of the concept can be most easily traced in patterns of publication. Already evident in J. Blair Smith's, Direct Action Versus Legislation (1898), pamphlets bearing the title “Direct Action” were regularly published in several languages: Émile Pouget, L'Action Directe (1903); Arnold Roller, Die direkte Aktion (1907); William Trautman, Direct Action and Sabotage (1912); and Voltairine de Cleyre, Direct Action (1912). The most notable of these were widely translated. Journals and newspapers bearing the title “Direct Action” likewise appeared in these years in France, Belgium, Germany, Norway, and Australia. “Direct action” was also the credo of Italy's leading socialist editor at this time, Enrico Leone.Footnote 1

The rise of the concept is perhaps more fully expressed in the affiliation of radical institutions. In the first years of the twentieth century, direct action was formally embraced by union and radical bodies across continental Europe, Great Britain and Ireland, America, North and South Asia, and Australia.Footnote 2 The transnational reach of the concept was explicitly recognized in a public invitation to the International Congress of Anarchists in Amsterdam, 1907; this justified the event partly on the basis that direct action had been “strongly” and “consciously inaugurated” across several countries in the recent past.Footnote 3

The importance of the concept has not been overlooked by earlier scholars and it has been selectively registered in previous treatments of the syndicalist movement. These studies have sought to trace and explain the history of “syndicalism” and have mobilized the concept of direct action in pursuit of this aim. Notable studies have defined “revolutionary syndicalism” as based on the method of direct action, or as the combination of trade unionism and direct action.Footnote 4 Others have associated syndicalism with a “direct action programme”, a “practice of action”, and an “emphasis on direct action”.Footnote 5

Partly since direct action has been offered as a means of defining syndicalism, there has been less effort to define direct action itself; it has rather served as a “black box” (in Bruno Latour's sense of the term), a question not posed. These historical works have commonly presented direct action as a set of practices largely unmoored from a theoretical or conceptual base. It has been depicted as a “spontaneous” and “pragmatic” orientation, with “action” explicitly contrasted with “theory” or “doctrine”.Footnote 6 Others have identified direct action with a specific ensemble of contentious performances: strikes, demonstrations, boycotts.Footnote 7 Mobilized in this fashion, the conceptual history of direct action has remained unexamined.

The folding of direct action into syndicalism is understandable: several of its leading advocates in the early twentieth century were themselves known to follow this practice.Footnote 8 But for the historian of direct action it is grossly insufficient, for it leaves unresolved three substantial historical questions. These questions divided partisans within the labour movement as well as the wider polity. They clearly establish that direct action was not simply a “pragmatic” mode of behaviour, but was itself an independent and important concept. They might be called “the problem of meaning”, “the problem of novelty”, and “the problem of nation”. They have not been identified or explained in previous, syndicalist-focused histories. They merit explication.

First, meaning. Though the term direct action was widely used from the early twentieth century, there was no agreement on precisely what it meant. This was partly a reflection of conservative caricature. In their efforts to stymie radicalism, its opponents associated direct action with a range of apparently malign behaviours: anarchist violence; terrorism; assassination; even murder.Footnote 9 This provoked confusion.

Such associations were in many ways inaccurate, for influential supporters of direct action explicitly rejected a necessary connection with violence.Footnote 10 They rather identified direct action with the “normal function of the unions”, and with performances such as the strike.Footnote 11 But the situation was more complex than wilful misrepresentation by a few critics, for many champions of direct action also freely admitted that the practice might extend to such violent behaviours as “economic and social terror”, “pillage” and “arson”, and “bombs and dynamite”.Footnote 12 There was no consensus, even among enthusiasts.

Not surprisingly, the plurality of definitions led many to despair of terminological clarity. At the Congress of the French Socialist Party (SFIO), 1908, one delegate described themselves as “not in principle averse to direct action, on the condition that someone tells me what it is”.Footnote 13 Other delegates complained of misleading definitions and explicitly disputed each other's attempts to define.Footnote 14 A similar situation prevailed in the United States, where one labour commentator claimed that “reckless” and confused applications of the term were evident even among the “honest” and those “supposed to have a fair knowledge of the movement”: “those who advocate this tactic seem to know the least about it”.Footnote 15

This terminological contest and apparent confusion raise an obvious difficulty for the historian of direct action. If there is no agreed definition of the concept, then how is it possible to trace its historical emergence? The historian of invention must solve the puzzle of meaning.

A second puzzle relates to novelty. For many, perhaps most, direct action was perceived as something new. Peter Kropotkin called it a “new birth”.Footnote 16 Other supporters spoke of a “new idea”, a “new means”, a “new tactic”, and a new “tendency”.Footnote 17 This was consistent with its framing as an alternative to “‘the old schools’ of socialism” and alignment with the future.Footnote 18

But this view was contested. Many advocates of direct action were keen to imagine it as a long-term feature of popular struggle rather than as a recent response to industrial modernity. “It is no novelty!” said the Syndicalist.Footnote 19 J. Blair Smith in Direct Action Versus Legislation agreed.Footnote 20 Supporters of direct action, such as Charles Albert, suggested that it had been “the tactic of anarchists while ever there have been anarchists”.Footnote 21 Writing in the Les Temps Nouveaux in 1907, Michel Pierrot pushed this back even further, arguing that “direct action has always existed”.Footnote 22

Later historians of anarchism and syndicalism have not resolved this conflict, rather reproducing positions earlier advanced by the activists of several generations ago. Direct action has been treated by some as a new presence in the early twentieth century,Footnote 23 and by others as an “old” idea or practice.Footnote 24 Long-term studies of contention led by Charles Tilly have reinforced the case for continuity rather than departure, identifying “direct” claim-making as a long-term feature of popular politics, stretching back several centuries.Footnote 25 Further investigation is therefore necessary to clarify the form and extent of any alleged novelty.

The third puzzle concerns the relationship of direct action to the nation. Was direct action the product of a specific national situation, a transnational network, or some combination of both? And if the nation and the transnational were both significant, then how can we specify their relative contributions and connections?

Many activists of the early twentieth century – French and otherwise – foregrounded the French identity of the concept. French examples and events were commonly invoked in treatments of the tactic in the US, Australia, Spain, Italy, Germany, and Latin America.Footnote 26 French writings on direct action were translated into Italian, Spanish, German, and English.Footnote 27 French champions of direct action proclaimed their influence on neighbouring labour movements.Footnote 28 And Germans such as Siegfried Nacht (writing under the pen-name of “Arnold Roller”) agreed that the concept of direct action was “first propagated from France”.Footnote 29

But evidence also points to influences from outside France. Many non-French pioneers of direct action were also commonly identified, among them the Italian Malatesta, the Russian Kropotkin, and the German Nacht.Footnote 30 Kropotkin was hailed as the author of the “bible of Direct Action” (his history of the French revolution).Footnote 31 Nacht was celebrated as the author of the “best” pamphlet on the topic.Footnote 32 In the English-speaking world, America's Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was thought to exert an influence as powerful as the French Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT).Footnote 33 And in the pages of the global labour press, exemplars of direct action were identified in spaces as diverse as Milan, Chicago, the London Docks, Spain, Belgium, Germany, and Japan.Footnote 34

Rather than the French, some observers looked for the origins of the practice further South. Though Nacht argued in Die direkte Aktion (1907) that the French had first “propagated” direct action, he also argued in another 1907 pamphlet, Blätter aus der Geschichte des spanischen Proletariats, that it was the Spanish, not the French, who were the first to “practice direct action” and to “employ the general strike”.Footnote 35 Similarly, Spanish anarchist Anselmo Lorenzo dated his embrace of the method to the period long before any codification in turn-of-the-century France, proclaiming that, “I have accepted direct action since the bloody repression of the Paris Commune”;Footnote 36 Lorenzo's history of the Spanish movement in the 1870s could be considered a vindication of this claim.Footnote 37

Can these apparently contradictory accounts be reconciled? Could direct action reflect both a geographically dispersed history of enactment and debate and an apparently decisive French influence? How were the national and transnational related? In the pages that follow, I seek to resolve this puzzle. I argue that “direct action” circulated across national boundaries over several decades, but that French radicals were especially influential in the assembly and articulation of the concept, and in its promotion. Consequently, direct action emerges as a “transnational” concept distinguished by a particular French influence.

Solving the Three Puzzles: Meaning, Novelty, Nation

In this article, I seek to explain the three outstanding puzzles around “meaning”, “novelty”, and “nation”. I pursue these tasks sequentially: first, clarifying the problem of meaning, and only then considering the issues of novelty and nation. In solving these problems, I offer the first sustained analysis of the transnational invention of direct action. This is not a fully global analysis, but it draws on materials published on several continents in four languages.

My primary quarry is pamphlets and newspapers published in English, French, German, and Spanish, supplemented by secondary scholarship. The use of newspapers and pamphlets reflects the advice of key protagonists. Peter Kropotkin, famed Russian anarchist and pioneer of direct action, emphasized the special insights offered by the close reading of these movement publications: a world of “social relations” and of “methods of thought and action” that “cannot be found anywhere else”. Fellow anarchist, Max Nettlau noted the process of sharing and republication that tied together the radical newspapers of these years: “a constant exchange of ideas from country to country by translation of questions of more than local interest”. Historians of radical transnational politics, such as Davide Turcato, have already demonstrated the value of following these dicta.Footnote 38 I aim to extend this approach.

Why are these matters of historiographical and theoretical significance? Students of anarchism and syndicalism have, in recent decades, already effectively documented the import of transnational relationships. Such research has established that these movements were powered by a dense network of transnational exchange, that this network connected key individuals and institutions, that it was rooted in broader patterns of migration, exile, and travel, that it was strongly based in the exchange of the printed word, and that it extended far beyond Europe, comprising relationships within and across the Americas, Asia, Africa, and Australia.Footnote 39 But this research has conventionally taken an institution (for example, the IWW), an individual (for example, Émile Pouget or Jean Grave), a movement (for example, Italian anarchism), or a space (for example, London), as its object of analysis.Footnote 40 It has not investigated the transnational production of a political concept.

There is no reason to assume that transnational forces will shape the history of a concept in ways isomorphic with individuals or institutions, or movements or spaces. A concept is distinct: less material, more diffuse, more easily transferred and transformed. By studying the transnational production of direct action, this research therefore broadens the historical analysis of transnational dynamics. This will enrich the transnational history of social movements, better documenting how, precisely, these movements acted as incubators of political ideas.

The history of direct action, of course, transcends the moment of its dramatic efflorescence in the years that straddle the beginning of the twentieth century. Contemporary students of social movements have noted its presence in later campaigns for: women's rights; peace; civil rights; colonial liberation; environmentalism; gay and lesbian rights and queer politics; and global justice, along with other campaigns.Footnote 41 One scholar-activist even recently posited direct action as the organizing principle of post-sixties protesters: a means by which they have transformed the nature and meaning of radicalism.Footnote 42

But if direct action unquestionably possesses a long, vital, and continuing history, then that history has not yet been the object of overt and close inspection. Charles Tilly's path-breaking examination of repertoires of political contention covered the period from the seventeenth century, but did not extend far beyond the middle of the nineteenth.Footnote 43 He did not register the rise of a repertoire of direct action among activists in the early twentieth century. No obvious successor has emerged to scrutinize the history of repertoires from the point at which Tilly suspended his detailed examination. The vast majority of the scholarship produced within the growing field of “social movement studies” has rather been focused narrowly on the period since the 1960s; it does not extend backwards to earlier years.Footnote 44 And most scholars of modern social movements continue to take “the movement” – be it labour, feminist, or whatever – as their prime object of analysis, treating the use of direct action as a subordinate aspect of that story. Consequently, no synoptic history of direct action has been written that directly and closely examines the rise of this phenomenon.

This article therefore makes a contribution to the field of social movement studies, as well as transnational history. It invites attention to direct action as a worthy object of historical analysis. It establishes the import of labour-movement networks to the production of ideas and practices that would be taken up by many social movements in later years. It also seeks to demonstrate the value of specific theoretical and methodological procedures to the reconstruction of that history, a matter taken up in the conclusion. In these ways, it might be considered both a first chapter in a broader history of direct action” and a provocation to the field of social movement studies.

The Puzzle of Meaning

If direct action was subject to a variety of definitions, then its meaning cannot be clarified simply by their inspection and comparison. This merely establishes a terminological contest; it does not contribute to its resolution.

A long-standing approach to intellectual history, associated with the so-called Cambridge School, and also with Reinhart Koselleck's “Begriffsgeschichte”, provides methodological guidance. Broadly, these authorities suggest that fundamental or basic concepts do not possess a fixed or agreed meaning, and that the meanings attributed to concepts shift over time. They stipulate that the historian focus not just on the meaning of terms, but on their use: on the agents who use a given concept and on their varying situations and intentions; on the process by which given principles might be used to justify or enable action; and on the relationship between given words and broader vocabularies.Footnote 45

This approach has not been widely employed in the study of radical ideas or of ideas generated in the twentieth century, though some have countenanced such a procedure.Footnote 46 Following these methodological strictures, and drawing on pamphlets and newspapers from four continents, it is possible to discern three principal ways in which activists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries used the term “direct action”. These three uses are analytically distinguishable, though they were sometimes practically intertwined. They could be called the categorical, the performative, and the strategic.

Categorical uses specified a relationship to the State. They aimed to distinguish between political actions that worked through the institutions of the bourgeois state and those that did not. Used in this sense, direct action was action without “any intermediary” and “without the intervention of representatives”.Footnote 47 It was contrasted with “electoral struggles”, voting, legislation, “parliamentary” action, and “parliamentarism”.Footnote 48

Used in this categorical fashion, activists sought to elevate direct action as more effective than its alternatives. Indirect action was depicted as slow and uncertain, quietist and fatalistic.Footnote 49 Conversely, direct action was presented as more immediate, self-reliant, and efficient. Here, IWW leader Big Bill Haywood is typical:

I believe in direct action. If I wanted something done and could do it myself, I wouldn't delegate that job to anybody. (Applause.) That's the reason I believe in direct action. You are certain of it, and it isn't nearly so expensive. (Applause.)Footnote 50

Though clearly presented as an alternative to parliamentary politics, when used in this categorical fashion, direct action remained a relatively abstract concept – a “tactic”, a “means”, a “way”, and a “method” – without further specification.Footnote 51 On occasion, however, the term could also be used in a more focused fashion, and applied to particular manifestations of struggle. This performative use of the concept did not simply signal a broad orientation to the State. It also referenced a cluster or repertoire of specific political performances.

Advocates named or labelled several public performances as versions of direct action. These included most prominently: the strike (often singled out as the “most common”, and most “efficacious” form);Footnote 52 the general strike;Footnote 53 the boycott; the trade-union label; stump or soapbox oratory in public space;Footnote 54 public demonstrationsFootnote 55 “co-operative experiments”;Footnote 56 and “sabotage”.Footnote 57 But these examples are only indicative, and many activists attempted to expand possibilities further. Some argued explicitly that direct action should not be considered “a fixed thing, a thing that never changes”, rather suggesting that it might be enacted in any number of ways.Footnote 58

When its promoters used the concept of direct action in this fashion, they embedded it in attempts to incite contention and to enlarge the possible range of political performance. Advocates aimed to encourage greater and more diverse forms of struggle: to nurture apparently novel contentious acts; to insist on their political efficacy; and to posit a family resemblance between them. Framing these interventions as direct action helped to fulfil these aims.

A third, strategic use of direct action did not address a relationship to the capitalist state or a particular repertoire of performance. It related rather to an axis of temporality. Used in this strategic fashion, direct action was posited as a means of connecting immediate struggles for reform and long-term aspirations for revolution – of bridging the present and the desired future.

The form and importance of this use of direct action are best appreciated when placed in a broader intellectual and political context. Over the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the workers’ movement was divided by often bitter debates over the possibilities of reform and their connections to revolutionary change. These were most obviously expressed in the debate triggered by German social democrat Eduard Bernstein. Famously, Bernstein rejected the notion that capitalism was bound to fall into an imminent crisis, or that socialist tactics should assume such imminence.Footnote 59 He advocated rather for the priority of political organizations “to fight for all reforms in the State which are adapted to raise the working classes and transform the State in the direction of democracy”.Footnote 60 Bernstein thereby imagined a new relationship between the immediate and ultimate, with the struggles of the present elevated above more distant hopes: “that which is generally called the ultimate aim of socialism is nothing, but the movement is everything”.Footnote 61

Bernstein's arguments were partly based on a close observation of English trade unionism and its sympathetic portrayal in the Webbs’ Industrial Democracy. Footnote 62 They therefore had implications for debates around the relationship between immediate and long-term struggles among European trade unionists. In practice, nearly all trade unions were necessarily concerned with the winning of immediate demands. This posture was widely shared and even championed by trade union leaders in Great Britain and the United States, and by many socialist leaders on the continent.Footnote 63

Conversely, many self-proclaimed “revolutionaries” deprecated the political possibilities of day-to-day union struggles. They presented such actions as guided by a desire for “amelioration” rather than “socialism”,Footnote 64 and as returning few advantages for the efforts expended.Footnote 65 These arguments would be most famously developed in V.I. Lenin's critique of “economism”, What Is To Be Done?, in which Lenin diagnosed the limits of trade-union struggles and prescribed a new kind of revolutionary party. But many of those who departed from Lenin's prescription shared his diagnosis. Notable supporters of the general strike typically drew a distinction between what were called “partial strikes” for limited aims and revolutionary strikes that sought socialist transformation.Footnote 66 French anarchist Fernand Pelloutier – a leading propagandist for the general strike – denied the possibility that the partial strike could achieve anything meaningful at all.Footnote 67 Contributors to Francisco Ferrer's Spanish journal, La Huelga General, agreed, arguing that the “utilitarian” or “reformist” strike would deliver only “apparent triumph”, “lost time” and “painful casualties”.Footnote 68

These prevailing and polarized viewpoints exposed “revolutionaries” working within the trade unions to acute tensions. Moderates presented them as “adversaries of all reform”,Footnote 69 or as dreamy utopians, unwilling to recognise the value of “practical action”.Footnote 70 This was not conducive to the winning of union elective offices or informal influence with the rank-and-file. But an immersion in day-to-day struggles was also dangerous ground. Adherents of socialism were anxious to maintain fidelity to a transformative vision, and not to exchange their hopes for a new order for the paltry promise of a “thick sandwich for tomorrow”.Footnote 71

Caught between these opposing forces, radical activists working within the union movement sought to use the concept of direct action in a distinctive and strategic manner. They used the concept of direct action to commit themselves to immediate struggle for improvements, but also to claim that these struggles possessed a revolutionary content. Direct action was a means of vaulting the binary between revolution and reform. Leading members of the CGT first articulated this position in a report to their 1903 Congress, subsequently published as a pamphlet, Grève Générale Réformiste et Grève Générale Révolutionnaire. Here, they denied that there was a “fundamental opposition” between “expropriatory” and “reformist” forms of the general strike, since both “rest on a common principle: the direct action of the working class”.Footnote 72

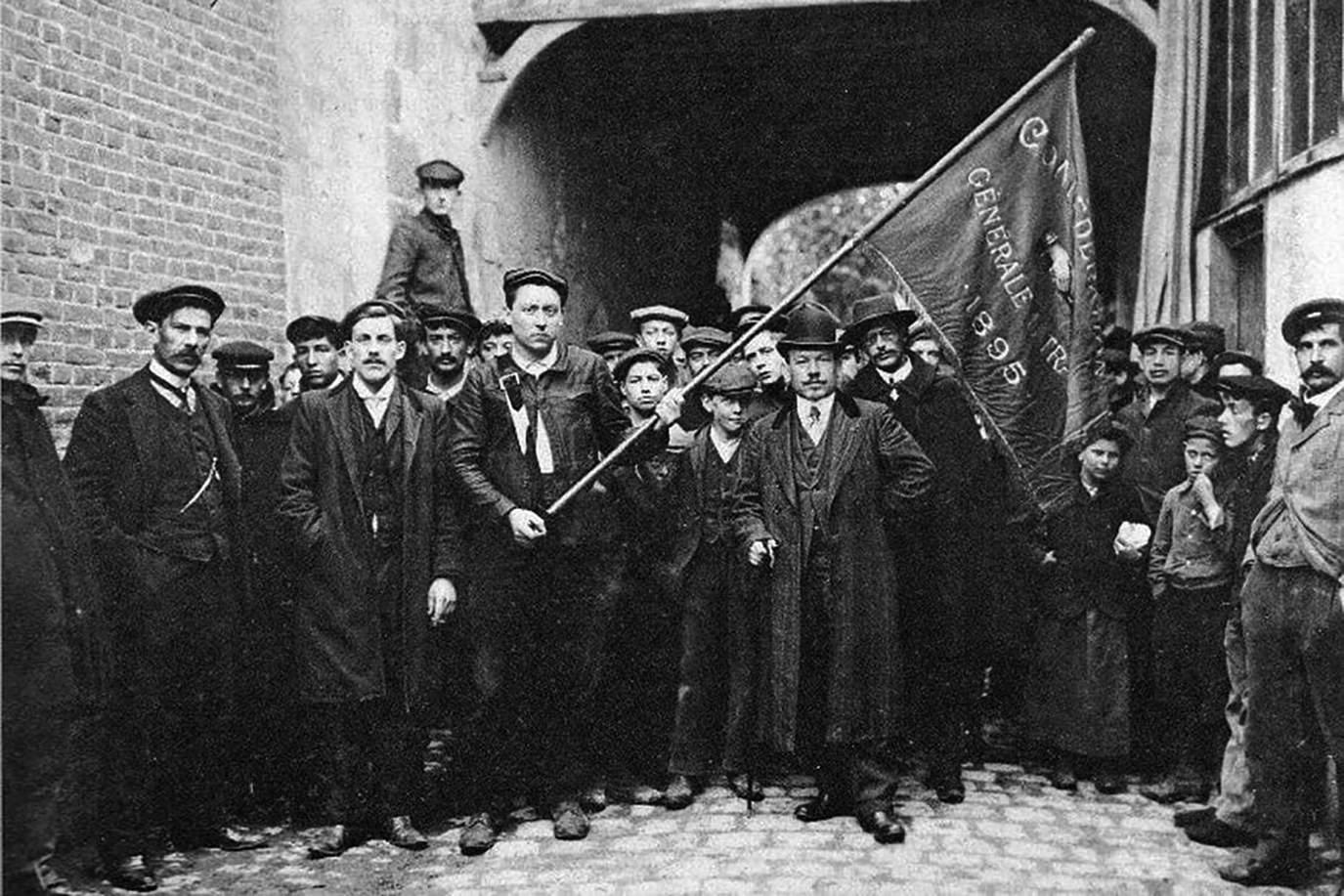

This strategic use of the concept of direct action was widely embraced at this time. Also in 1903, editors of the inaugural issue of the Parisian journal L'Action Directe argued that direct action was both revolutionary and “the best means of being truly reformist” (this was because reforms were only obtained by “intense struggle” and not by “begging”).Footnote 73 In successive issues of the journal, contributors agreed that direct action straddled the apparent division between revolutionaries and reformists.Footnote 74 As leading propagandist Émile Pouget put it: “reform and revolution are not exclusive and are simply phases of action of differing intensity”.Footnote 75 By 1906, this position had become hegemonic within the CGT, registered in the famous Charter of Amiens, with its affirmation of the import of both “immediate ameliorations” and of preparations for the “complete emancipation” of the worker, attainable only with “capitalist expropriation” (Figure 1).Footnote 76

Figure 1. In 1906, during their ninth congress in Amiens, the CGT adopted a text that was to have a lasting impact on French trade union history. This Charter of Amiens also had a transnational impact as a statement of revolutionary unionism.

Public domain, CC0.

From the Problem of Meaning to the Puzzles over Novelty and Nation

Distinguishing between the different uses of the concept of direct action also clarifies what I have called the problem of novelty and the problem of nation. The different uses of direct action (categorical, performative, strategic) each implied a different history and a different connection to activists in France. In the following section, I systematically review these differences.

Categorical uses of direct action were evident from at least the early 1890s. Kropotkin's English-language journal Freedom referenced “direct ‘revolutionary’ action” in this categorical sense in 1890 and 1891, and “direct action” in 1893.Footnote 77 Kropotkin also wrote of “direct struggle” in the French anarchist journal Les Temps Nouveaux 1895.Footnote 78 Though the exact vocabulary was not always used, earlier contributions to international socialist debates often drew a categorical distinction between actions oriented towards the bourgeois state and actions separate from and antagonistic to state institutions. Writing in the early twentieth century, Dutch syndicalist Christian Cornélissen suggested that, when considered in this wider sense, the concept of direct action was present from the early 1870s.Footnote 79 Anselmo Lorenzo's reconstruction of Spanish contributions to the First International, El proletariado militante also emphasized the importance of a self-consciously anti-Statist current in the early 1870s.Footnote 80

There is no evidence that the French were especially precocious in the categorical use of this concept. Considering the Francophone world, noted French historian Jacques Julliard thought the term direct action was not widely used before 1900.Footnote 81 An allied view – put by an American journalist in 1912 – was that the term had first been used by leading French anarchist, Fernand Pelloutier, in 1897.Footnote 82 Others pushed the date back slightly earlier,Footnote 83 but none suggested the 1870s. Existing evidence suggests it is highly unlikely that the French embraced the categorical use of the term in advance of anarchist and socialist activists based in other lands.

Considered in performative terms, direct action also had a relatively venerable and transnationally dispersed history. Each of the major performances associated with direct action were used and promoted outside France long before the rise of direct action as an explicit concept. Moreover, the most prominent advocates of direct action – French and otherwise – publicly recognized these earlier histories and drew explicit attention to important precedents. Such a public acknowledgement is evident with regard to those performances most commonly identified and promoted in the first writings dedicated to direct action: the strike (especially the general strike); the boycott; the trade-union label; and sabotage.Footnote 84

French radicals strongly embraced the possibilities of the general strike from the late nineteenth century. Union congresses formally supported the action. Leaders of the anarchist and socialist movements published a succession of influential pamphlets: Fernand Pelloutier and Henri Girard, Qu'est-ce que la grève générale (1895); Aristide Briand, Discours sur la grève générale (1899); Georges Yvetot, Vers la grève générale (1902); Hubert Lagardelle, La grève générale et le socialisme (1905), among others. Fifty-thousand copies of the CGT's pamphlet, La grève générale réformiste et la grève générale révolutionnaire were published in 1903. Propagandists in other countries drew favourable attention to these developments.Footnote 85

But this did not mean that the general strike was especially associated with France. The 1886 Chicago strikes for the eight-hour day and the London Dock Strike of 1889 were widely regarded as the first major strikes to galvanize the attention of radicals to the possibilities of trade-union action;Footnote 86 even in the later 1890s, the French radical press continued to advertize pamphlets devoted to that preceding British event.Footnote 87 The Barcelona general strike of 1902 provided further vindication of the method. In Blätter aus der Geschichte des spanischen Proletariats, Nacht argued that it was this event – not any French mobilization – that had stimulated “truly intensive propaganda” in Europe for the general strike.Footnote 88 Further notable manifestations were evident in the early twentieth century in Belgium, in Sweden, in the Netherlands, in Italy, and as part of the Russian Revolution of 1905,Footnote 89 though not in France. Hubert Lagardelle – Paris-based editor of Le Mouvement Socialiste – organized his influential La grève générale et le socialisme by assembling commentary on the general strike from across the world's labour movement;Footnote 90 this was in no sense an identifiably French project.

The boycott was famously first named and practised in Irish struggles over land from 1880.Footnote 91 Its French promoters foregrounded these “revolutionary” and Irish origins, as well as subsequent use in struggles for industrial rights in England, Germany, and especially the United States.Footnote 92 They presented themselves as more laggard than vanguard in experiment with this method,Footnote 93 a position shared by radicals in Spain, who likewise underlined English, German, and American successes.Footnote 94

The trade-union label or “marque syndicale” was applied to goods produced under union conditions. It served as a signal to consumers and as a reinforcement to union mobilization. Like the boycott – with which it was sometimes linked – the technique was also promoted in France on the basis of its already successful application in the United States. This was evident at successive French trade-union congresses in 1900 and 1904, and in detailed accounts in radical French journals.Footnote 95 It was a position again shared by Spanish propagandists.Footnote 96

“Sabotage” is a French word and in later years the practice would be very strongly associated with France. Surprisingly, however, French radicals initially traced this practice to roots outside France. The concept first officially entered discussions in the French labour movement at the Toulouse trade union Congress, 1897. A report, written under the influence of anarchists Paul Delesalle and Émile Pouget, identified a pre-history in the English (and especially Scottish) practice of “Ca’ Canny” or “Go Slow”. The basis of this policy was the credo: “For Bad Pay, Bad Work”. Delesalle and Pouget sought to promote this practice in France under the French term “sabotage”.Footnote 97 The quest can be traced back to the journal Pouget edited while in a period of London exile, La Sociale. In an 1896 contribution to this journal, Pouget had already called for “Sabottage” (this spelling was common at first) without explicit reference to the term “Ca Canny”, but by deliberate reference to “the English maxim: ‘For Bad Pay, Bad Work’”.Footnote 98

There is ample evidence of discussion of the principle of ca canny outside France. Drawing on experiences on the London docks, Tom Mann sought to promote the practice in transnational struggles on behalf of maritime labour; the International Federation of Ship, Dock and River Workers he led even produced a pamphlet, “What is Ca’ Canny?”.Footnote 99 Historians of the French labour movement, such as Constance Bantman, have previously emphasized the import of English precedents to the development and articulation of sabotage as an explicit industrial technique. Students of the American labour movement have also traced a passage of influence from the United Kingdom to the United States in which maritime unionists played a leading role.Footnote 100

Considered as a series of distinct performances – the strike, the boycott, the label, and sabotage – there is, therefore, no evidence of French precocity or of fin-de-siècle creativity. As with categorical uses of direct action, there is rather evidence of transnationally dispersed use long before the turn of the century.

This does not mean that it is adequate simply to ascribe the rise of direct action to a transnationally dispersed network of radicals. Nor would it be accurate to contend that French radicals made no distinctive or decisive contribution to the invention of direct action. On the contrary, I want to suggest that they made important contributions to both the performative and strategic uses of direct action. These contributions took two significant forms: assembly and strategic articulation. Through these two activities, French radicals connected previously disparate political performances, embedded them in a strategic path to revolution, and promoted this new combination across the world. These efforts were central to the invention of direct action as a transnational concept. They would exert a significant transnational influence.

A Decisive Influence: French Radicals, Assembly, and Strategy

The key performances associated with direct action had long and spatially dispersed histories. However, before French interventions in the late nineteenth century, these performances were not understood as a connected repertoire capable of winning revolutionary transformation. When radicals outside France promoted and enacted performances like the strike, the boycott, and the label, they did not conventionally present these as an integrated means of seeking transformative change. They did not promote sabotage at all.

Those labour movements that most fully deployed the strike, boycott, and label tended to understand them as discrete performances for limited gains. The strike was conventionally framed as a singular event, which did not imply complementary activities. As one contributor to the Bulletin De L'Internationale Anarchiste complained, workers in countries such as England did not “understand quite enough the importance of action in a strike”.Footnote 101 As German socialist Robert Michels lamented, the German unions increasingly followed the English example.Footnote 102

At times, these methods were even presented as alternatives rather than complements. One contribution to the Brauer Zeitung, the bilingual newspaper of the American Brewers’ Union (edited by future IWW leader and future proponent of direct action, William Trautmann) asked in 1902: “Seriously now, if we carried out to the full our trade union policy on the label question, would there be any need for boycotting?”Footnote 103 Another contribution in 1903 reported that: “Persistent, insistent and intelligent union label agitation has, in many instances, accomplished what the strike and the boycott have failed to accomplish.”Footnote 104

Though each of these performances had its champions, few argued for their common identity and mutual reinforcement. It was only in the process of crossing into France in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that they were more deeply intertwined. That process of enlacing was accomplished in three analytically separable stages, spread over a number of years.

First, sabotage was introduced as a complement to the boycott and the strike. At the French trade union congress in Toulouse, 1897, the “Rapport de la Commission du Boycottage” championed sabotage as “a tactic of the same essence” as the boycott and an “indispensable complement” to the boycott.Footnote 105 A resolution passed at the Congress noted that, in situations in which “the strike” was not able to deliver “the results workers sought”, they should apply “the boycott or sabotage – or the two simultaneously”.Footnote 106 No previous formulation had presented these methods as a connected means of struggle. French campaigners did not invent these performances. But they were the first to identify them with each other and to advocate the possibility of connected use.

Second, a Commission at the Trade Union Congress in Paris, 1900, explicitly introduced the union label as an addition to this duo, and further justified the label as a complement to the boycott. As it argued explicitly: “The trade union label is tightly connected to boycotting […] the two systems which seem to be diametrically opposed have the great virtue of leaving from two different points and of arriving at the same goal.”Footnote 107 In this way, over successive trade union congresses, French unionists declared adherence to the strike, the boycott, sabotage, and the label, and further proclaimed their common bases.

Third, in the aftermath of these formal congress decisions, French propagandists began to explicitly frame the joint performance of the boycott, the strike, sabotage, and the label as sharing the common identity of direct action. Influential advocate Émile Pouget – a key figure on the 1897 Commission du Boycottage – led the way, describing these four performances as versions of direct action in his influential pamphlets Le Syndicat (1904) Le Parti du Travail (1905) and La Confédération Générale du Travail (1908),Footnote 108 and in contributions to journals such as Le Mouvement Socialiste.Footnote 109 Other union and anarchist journals also took up this formulation, though sometimes dropping the label (to form a trio rather than a quartet of key performances), or substituting a more generic “etc.” for performances beyond the strike, the boycott, and sabotage.Footnote 110

This understanding of direct action as an assemblage or repertoire organized around three key performances – and sometimes expanding to include others – soon became hegemonic. This status was both reflected and reinforced with George Yvetot's A.B.C. Syndicaliste – praised as the “practical manual of syndicalism”, printed in tens of thousands, and the most widely read of all syndicalist works.Footnote 111 Yvetot emphasized that “direct action varies according to the circumstances”, but in his discussion of “Methods of Action” and “direct action” he gave pride of place to sabotage, the boycott, the partial strike, and the general strike.Footnote 112 In this way, through a process of intensive discussion and decision-making within the French labour movement, activists established that direct action possessed an agreed performative core. A repertoire of direct action was publicly named and its first defining elements agreed.

The contribution of French radicals to the invention of direct action went beyond these important interventions. The French not only connected previously disparate performances under the concept of direct action, but they also embedded these interventions in a strategic discourse, so that the performance of direct action was understood as a revolutionary act. This process of strategic articulation was enacted in three primary modes.

First, French activists persistently framed the performance of what they called direct action as revolutionary in character. This partly involved the generous application of the descriptor “revolutionary” to the new term. Direct action was “revolutionary”, “the revolutionary method”, “revolutionary action”.Footnote 113 But key performances were also framed in these terms. The boycott was said to possess “revolutionary” roots.Footnote 114 It was conceded that the label “is not in appearance a manifestation of revolutionary flamboyance”, but equally insisted that it “derives no less from the same principle: the workers struggle to defend themselves against capitalism, directly and by their own forces, without resting on an external power”.Footnote 115

Second, the strategic and revolutionary character of direct action was explicitly justified in argument. It was explained that performances such as strikes, boycotts, and sabotage were revolutionary because they trained workers in the methods of struggle, and they inspired workers to future rebellion. Campaigns for wages were “preparatory struggles” for a future revolution, it was said, stimulating in participants “the idea of revolt”.Footnote 116 Direct action was “educative”, a “school of revolution”, or a “school of will, of energy, of fruitful thought”.Footnote 117 The metaphor of “gymnastique” was sometimes favoured, with the performance of direct struggles, such as strikes, said to enhance the fitness and capacity of the working class, thereby equipping them with the ability to overthrow the existing order.Footnote 118

Third, many propagandists for direct action also posited a political sequence, through which strikes, boycotts, and sabotage would be broadened into a revolutionary general strike. The CGT's “Commission des Grèves et de la Grève Générale” (1903) was the most influential and early articulator of this view, suggesting that “a series of ever widening conflicts” would propel the workers movement from “reformist” strikes to a “final” revolutionary general strike.Footnote 119 But in succeeding years, many other propagandists (among them Hubert Lagardelle and contributors to Les Temps Nouveaux) echoed this expectation.Footnote 120

Émile Pouget perhaps expressed this standpoint most fully. In his history of the CGT, Pouget argued that “partial modes of action” such as “the strike, boycotting and sabotage” were “prodromes” or early symptoms of the expropriatory general strike.Footnote 121 Going further in his jointly written utopian text, Comment Ferons La Révolution (1909), Pouget and co-author (and leader of the electricians’ union) Émile Pataud, imagined a future revolution as the outcome of a series of interlocking acts: a strike (in the building industry, met by police repression); sabotage; a general strike; the seizure of workplaces (defended against police attacks by “non-resistance”); trade union organization of production; and the use of the boycott against “parasites and exploiters”.Footnote 122 This vision was not universally accepted. But its account of the revolution growing out of a series of smaller manifestations of direct action was certainly the object of debate (Figure 2).Footnote 123

Figure 2. Postcard, “La Manifestation du 1er Mai a Paris. Devant la Bourse du Travail”. On 1 May 1906, a banner demanding the eight-hour work day was displayed at the Bourse du Travail in Paris. This demonstration formed part of the CGT's attempts to win reduced hours through direct action.

Public domain, CC0.

It was these French interventions that forged direct action as a new and basic concept of labour-movement politics. Though the French movement was no vanguard in the winning of industrial victories, the writings of its key activists spread widely. As one contributor to the German anarchist journal Der Revolutionär put it, French propaganda moved “not the mass of their fellow countrymen alone”, but rather crossed the borders and awakened “an echo in the hearts of the exploited of neighbouring lands”.Footnote 124 French debates on the general strike were frequent points of reference in Spain and Italy. This included pamphlets produced by the CGT, speeches by French socialists, and texts written by French union leaders such as Pouget, Yvetot, Griffuelhes, and Pataud.Footnote 125 Émile Pouget was translated and reproduced in English, Spanish, and German;Footnote 126 his works circulated in North and South America,Footnote 127 and he was even quoted at the key IWW Convention that marked a decisive turn away from party politics.Footnote 128 Pouget was also a frequent presence in the pages of pioneering Italian journals of syndicalism, Il devenire sociale and Pagine libere, accompanied by the writings of other French activists and intellectuals.Footnote 129 Argentinian anarchists, for their part, reproduced key congresses of the French CGT in their weekly, La Protesta Humana, emphasizing “the importance of the new tactics” that the French imparted.Footnote 130 They underlined the French origins of key direct action tactics, such as the general strike.Footnote 131 And they deployed the French spelling of other performances, such as “Boycottage” and “Sabotage”, signifying the French influence.Footnote 132

The import of the French assemblage is perhaps most fully expressed when tracking transnational discussion of direct action. In the aftermath of French interventions, radicals in other countries began to reproduce the French formulation: framing the strike, the boycott, sabotage, and often the label as the core of a direct action repertoire; sometimes suggesting further performances; imputing direct action with a capacity to make revolution. The reproduction of this assembly – often, though not invariably, with reference to French authorities – is strikingly evident across Europe, North America, South America, and beyond.

In Italy, Errico Malatesta's L'Agitazione almost immediately embraced and promoted the decisions taken at the Toulouse trade union congress, with its emphasis on the strike, the boycott, and sabotage as connected forms of direct action.Footnote 133 Argentinian anarchists were also quick to promote these decisions, first in the pages of La Protesta Humana,Footnote 134 but soon afterwards at the second congress of the Federación Obrera Argentina, 1902.Footnote 135 Workers congresses in Belgium and in Brazil also discussed the French triumvirate of the strike, the boycott, and sabotage in the first years of the new century.Footnote 136 And at the 1907 Congress of the Anarchist International in Amsterdam, prominent leaders including Malatesta, Emma Goldman, and Christian Cornélissen presented a motion that referenced strikes, boycotting, and sabotage as “manifestations of direct action”, and that further committed its supporters to revolution and the general strike. The motion passed by thirty-three votes to ten.Footnote 137

French efforts to combine the strike, the boycott, and sabotage were also adapted in a series of influential pamphlets in German, Italian, Spanish, and English. Nacht's 1907 pamphlet Die direkte Aktion was celebrated as the “best” pamphlet on the topic of direct action, its “striking arguments”, “strength”, and “elegance” especially praised.Footnote 138 Nacht, in turn, was greatly influenced by Pouget's writings, and these formed the “stylistic and ideological model” for his publications.Footnote 139 Like Pouget, Nacht defined direct action and introduced to a German readership performances such as “Sabot” or “Go-canny” alongside more familiar activities, such as the strike. He also presented the “social general strike” as the apex of these more immediate tools and identified the ensemble of direct action as a revolutionary trade-union tactic.Footnote 140

Enrico Leone's Il Sindicalismo, also first published in 1907, still more faithfully reproduced the French repertoire of the boycott, sabotage, and the label as central expressions of direct action, while also underlining the efficacy of the general strike.Footnote 141 Influential Spanish anarchist Anselmo Lorenzo offered a fuller treatment (with chapters devoted to the boycott, the label, sabotage and the general strike) in his 1911 work, Hacia la emancipación. Los nuevos métodos de lucha. El syndicalism, enseñza racionalista, el boicote, marca label, sabotaje, huelga general.Footnote 142 He subsequently assured French readers of the Parisian journal, La Bataille syndicaliste, that the Left of the Spanish movement was committed to “l'action directe”, and that striking workers had recently acclaimed “the usefulness of sabotage” to rousing ovations.Footnote 143 Many Spanish readers had already been introduced to key elements of this ensemble in the Argentinian pamphlet De los Métodos de Lucha (eficacia del Boicot y Sabotagge) in 1904.Footnote 144

English-speaking readers were initially reliant on translations of works from other European languages and slower to draft pamphlets that took up the French assembly. But English reportage of French events as early as 1909 did begin to identify direct action with boycotting, sabotage, and the strike.Footnote 145 Louis Levine's 1912 academic study, The Labor Movement in France: A study in Revolutionary Syndicalism discussed direct action in some depth and, in doing so, reproduced Pouget's quartet of the strike, the boycott, the label, and sabotage. This book, in turn, served as a point of reference for often mono-lingual English-speakers with an interest in the concept. Levine's work was reproduced or discussed in several publications in the United States and the United Kingdom.Footnote 146

It was only with William Trautmann's Direct Action and Sabotage (1912) that a pamphlet written in English by union militants began to propagate the new ensemble.Footnote 147 Trautmann was a leader of the Industrial Workers of the World and this publication formed part of a major effort by IWW to promote direct action. Trautmann's pamphlet was soon “going like wildfire” across the United States.Footnote 148 The IWW quickly exerted a substantial global influence, especially marked on the anglophone world.Footnote 149 Perceptive Australian intellectual, Vere Gordon Childe, thought the IWW the key popularizer of direct action in his country.Footnote 150 But the paths of influence within the English-speaking world were often crooked. The IWW influence was also prominent in Scotland, and Scottish syndicalists, in turn, spread the doctrine to South Africa.Footnote 151 Tom Glynn, an Irish-born tram driver, became most active as a syndicalist in South Africa, where he was jailed and blacklisted, and he then ended up in Australia, where he acted as editor of the local IWW's newspaper, entitled Direct Action (Figure 3);Footnote 152 his pamphlet, Industrial Efficiency and Its Antidote (1915), explained to Australian readers that “‘Scientific Management must be met by ‘Scientific Sabotage’”.Footnote 153

Figure 3. The Sydney newspaper Direct Action, 31 January 1914. Note the words atop the front page: “All forms of DIRECT ACTION are Labour's best tactics. GET BUSY!”

Public domain, CC0.

The lines of interlacing were complex, and I make no claim to comprehensiveness. There are many further circulations of direct action that I have not documented here. These include the history of direct action in Japan, promoted by socialist Kōtoku Shūsui after contact with the IWW in San Francisco.Footnote 154 They also include circulations across Latin America, under the influence of the Federación Obrera Regional Argentina, along with the IWW.Footnote 155 But on the basis of the evidence presented here, it is abundantly clear that by the cusp of World War I, direct action had become an important concept in the global labour movement. It is also evident that French activists played a crucial role in the assembly of its performative core and the articulation of its role in a revolutionary strategy.

Context and Explanation

If the analysis presented here has reconstructed for the first time the transnational invention of direct action, then how should this complicated sequence be explained? Why the combination of geographic dispersal and French assembly and articulation? If the elements of the concept were present in many spaces, why were they first assembled and promoted in France?

The key role of French activists reflects not simply their admirable creativity, but also the particularities of the French context. French activists took the lead because of their experiences, institutional environment, and status.

Leading French activists had endured exile in the 1890s, and this had widened their knowledge of other labour movements and of possible tactics. France was a Republic, and so its working-class militants were less credulous as to the promise that parliamentary democracy would offer a path to socialist transformation; men enjoyed the franchise, yet their society was disfigured by great poverty and pronounced inequality. French socialist parties were various and highly schismatic, so that distance from their manoeuvrings and from “politics” was likely to appeal to proponents of union mobilization.Footnote 156 And some French socialists sought to turn unions into “recruiting adjuncts to the party”,Footnote 157 so that “politics” could even imply subordination.

It is therefore understandable that many French radicals were less than sanguine about politics, a stance strengthened by the historical import of anarchist ideas and groups.Footnote 158 But if formal politics implied disappointment, then the anarchist “propaganda of the deed” in the 1880s and 1890s appeared to inspire only great repression.Footnote 159 And the French union movement was not at first an obvious source of radical confidence. French workers were less unionized than their equivalents in the United Kingdom or Germany, and their unions lacked the financial resources of equivalent bodies. French employers were frequently hostile, and unions struggled to put down roots in often small workplaces; the municipality rather than the plant was the basic unit of organization.Footnote 160

This institutional environment encouraged decentralized (and sometimes covert) tactics, such as sabotage and the boycott, for militants could not expect that the withdrawal of labour from an employer would win success.Footnote 161 It promoted industrial actions across workplaces. Historians have also established that weak French unions often secured their victories through state intervention.Footnote 162 They have further established that this stimulated noisy and generalized mobilizations, for contentious and potentially threatening actions were more likely to compel the state to step in.Footnote 163

French radicals based in the union movement were therefore emboldened to experiment with many industrial and political tactics beyond the strike, to encourage the generalization of the strike, and to present these various actions as a unified challenge to power. These actions were attuned to the prevailing industrial circumstances in France. Though widely understood as an expression of revolutionary threat, they partly reflected the relative weakness of French unions and the difficulties of achieving their demands.Footnote 164

Why might this cluster of performances be presented as a revolutionary strategy? France was the heir to the most celebrated revolutionary tradition in modern history, so that revolution loomed as the dominant imaginary of political change. French socialist parties cleaved to the language of Marxism and their leaders were often adept theoreticians.Footnote 165 A rival vision of change needed to meet its competitors on this theoretical terrain.

The French activists who came to argue for a strategy of direct action had a political base in anarchist and socialist journals published in Paris – most notably Les Temps Nouveaux, L'Action Directe, and Le Mouvement Socialiste – and in the trade unions themselves. From 1887, trade unions had begun to organize through locally based Bourses du Travail [BdT] or labour exchanges. Over the later nineteenth century, these became more numerous and more politically significant: providing libraries, workers’ education, and industrial community – an “association of resistance”, aspiring to a “State within the State”, claimed the leader of the Fédération des Bourses du travail, and their first historian, Fernand Pelloutier.Footnote 166 Union bodies also gathered together at periodic conferences, forming a Confédération Générale du Travail in 1895. And in 1902 the CGT and BdT were united.

Self-proclaimed revolutionaries held the leadership of the CGT and the BdT over the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They surveyed in these years more than a decade of growth. More French workers were joining unions, they were more willing to initiate strikes, and these strikes were becoming more generalized and more successful. Union membership increased from 614,000 in 1902 to 1,027,000 only a decade later.Footnote 167 The rate of strikes per 100,000 workers increased sixfold – and in relatively steady fashion – from 1885 to 1914.Footnote 168 And strikes led by revolutionary syndicalists enjoyed far greater success than those led by reformists.Footnote 169 There was also evidence that militant action was compelling remedial government measures: concessions to try to manage social conflict. But while these developments emboldened confidence in the possibility that direct trade-union struggle might lead to socialism, some opponents within the unions sought to win support for a rival programme of reform. Reformists held office in many of the largest and most influential unions affiliated to the CGT; one historian has claimed that they made up “as much as half of its membership”.Footnote 170 And reformists could claim that the victories of the fin de siècle demonstrated the possibilities of practical change under capitalism.

In proclaiming an overt strategy of transformation through direct action, revolutionaries in the CGT expressed their hopes and countered their opponents. The new concept reflected the recent momentum of the French labour movement and the successes won by contentious performances, amplified by the most radical rhetoric. It parried internal critics within the union movement, since it promised that the revolutionary was also the fiercest fighter for immediate demands. But it also challenged the leaders of the socialist parties – revolutionary and reformist – since it used the language of Marxism to outline how socialism might be won by autonomous trade-union struggle.

The theory resonated widely, for if it was crafted in response to industrial and political circumstances in France, then the tensions it sought to manage were shared with many other labour movements. The elective franchise had been extended in several polities, working-class and socialist representatives had been elected in a number of countries, and disappointment and disaffection had everywhere trailed in their wake. An “anti-political” message therefore chimed with recent experience.

If French trade unions were less institutionally robust than those in Germany and the United Kingdom, in these and other jurisdictions the formal acceptance of the institution had seemingly brought with it incorporation and stasis.Footnote 171 Radicals here and elsewhere sought a language and a justification for a more militant and independent stance; direct action provided such an authority.

It was not only that the new concept of direct action resonated with circumstances outside France, its promulgation by French radicals also brought it a particular prestige. The long-established revolutionary tradition in France meant that many elsewhere understood its politics as the vanguard of likely international trends – the “home of all revolutions”, as Big Bill Haywood put it.Footnote 172 And the cultural centrality of Paris – the concentration of journals and newspapers; the interest of outsiders in Parisian debates; the importance of French as a language of international exchange – ensured that any new French theory would be widely communicated and keenly discussed.Footnote 173

These long-term features of the context were reinforced by developments of the early twentieth century. French “direct actionists” refined their doctrine in response to a wave of industrial disputation. These events were conveyed to radicals in other lands, enhancing the authority of French claims on the basis of what Emma Goldman called their “beneficial practical results”.Footnote 174 French workers were less likely to join unions, it was true, but on the other hand the CGT was the only peak body in Europe or North America led by openly declared revolutionaries.Footnote 175 This strengthened the appeal of a direct action minted in France, especially for revolutionaries who sat on the margins of the labour movement in other countries.

Of course, none of this should imply that the transfer of direct action outside France was automatic or seamless. Its allegedly French character alienated some activists in other countries, and certainly proved a pretext for critics to declare its “foreignness” and inappropriateness.Footnote 176 And even when it was successfully translated into other national contexts, that translation also implied an adaptation: a remaking or reinvention to reflect differing circumstances.

While the French assembly was widely taken up – as I have shown – it was also subtly remade in other domains. In Mexico, the promoters of direct action more vigorously associated with its relationship to insurrection, doubtless reflecting a context of revolutionary war.Footnote 177 Radicals in Germany faced a highly repressive state, and direct action here also appeared to be more strongly interlaced with overt calls to violence; writing for a German audience, Nacht underlined the relationship between direct action and economic and social terror, extending even to terrorism against the person of the capitalist.Footnote 178 In strongly Catholic Spain, secular rationalism was explicitly identified as an element of direct action, alongside the boycott, the strike, and sabotage.Footnote 179 American radicals, battling for free speech, came to present their tradition of “stump” or “soapbox” oratory as a manifestation of direct action.Footnote 180 Some also highlighted the import of a specifically “industrial unionism” to be fused with direct action, and came to argue that “the I.W.W. goes much farther in its methods of attacking the capitalist state and the employing class than the C.G.T.”.Footnote 181 In Australia, where a system of compulsory arbitration regulated employment relations, it came to be understood as a practice of industrial militancy that rejected compromise and delay and refused the dictation of the state.Footnote 182 These examples could be extended. The underlying point is that the French “assembly” of the early twentieth century would not remain fixed through later intercrossings. The subsequent history of direct action is as complicated and shifting as its invention.

Conclusion

Direct action is a fundamental concept of social movement politics. Its origins have not previously been carefully investigated. Close analysis establishes that the concept emerged in the years that straddled the beginning of the twentieth century. The concept's meaning was contested, and it was used in a series of overlapping ways: as category, as performance, as strategy. The invention of the concept drew upon long-term and transnational exchanges and inspiration from activists and struggles in many lands. But activists based in France made decisive and catalytic interventions, and it was a new assembly forged in France that was rapidly diffused across the transnational labour movement.

It is therefore inadequate either to proclaim the essential “Frenchness” of direct action or to assert simply that it has a more dispersed genealogy, encompassing Spain, or Germany, or wherever. It is necessary rather to recognize both the import of a vital transnational network and the transformations wrought by crossing into and through France, as French radicals initiated a novel recombination of elements, out of which a more coherent, prominent, and influential concept was made.

These findings reconstruct a previously underexamined element of labour-movement history, but they also have wider implications for the practice of transnational history. They establish the possibility of pursuing a transnational history of concepts. They suggest that this history cannot be adequately appreciated as a transfer of prefabricated packages (English Fabianism, German social democracy, etc.), for this implies a nationally distinct and insulated beginning that cannot always be sustained. It also overlooks how the process of intercrossing can itself be productive, triggering the transformation and recombination of elements. Readers will recognize that these findings echo the principles of “histoire croisée”, first articulated by Michael Werner and Bénédicte Zimmerman a decade and a half ago.Footnote 183 The transnational history of political concepts is best pursued as a “histoire croisée”.

This article has further enacted methods through which such a history might be pursued: extensive use of newspapers and pamphlets (and not simply a few most notable texts); close contextualization; attention to differing ways in which concepts might be put to use; consideration of how these uses might be assembled and reassembled in different combinations; the tracing of how specific combinations attracted heightened prestige and prominence, and were then taken up and reused with particular frequency and impact. It is not sufficient to document the presence or transmission of a keyword across dispersed texts, but necessary further to embed it in cross-cutting political projects and complicated and themselves shifting networks of power and authority.

The article also has implications for the study of social movements. Many activists continue to practice direct action and to debate its meaning and application. Surprisingly, however, students of social movements have not generally considered the concept of direct action worthy of detailed analysis. There has been no earlier attempt to reconstruct and explain its invention. Most labour historians have treated it simply as a pragmatic posture, devoid of intellectual content. Most scholars who identify as practitioners of social movement studies have shown little interest in campaigns before the 1960s, let alone in the ideas that they produced.

I hope in this article to have demonstrated that direct action in the early twentieth century was a rich and multi-layered concept, encompassing a broad principle of categorization, a repertoire of performances, and a strategy of political transformation. I hope further to have shown that the labour movement can be considered the collective author of this concept, so that a full appreciation of modern social movements – their ideas and their practices – cannot afford to put labour, or labour's history, to the side.