The voyage of the Zong is an infamous one. That slave ship left West Africa in 1781 bound for Jamaica. Scores of those on board were killed by one of those epidemics that not infrequently visited slavers, particularly before the age of parliamentary regulation. After more than sixty slaves had died, illness continued to rage and, when the ship accidentally bypassed Jamaica, with the adequacy of its water supplies in question, the Captain ordered the drowning of 133 slaves. Opponents of the slave trade were convinced that those chosen for death were seriously ill or in such poor condition that they would fetch little or nothing in the Jamaica slave market.Footnote 1 Before the courts, however, counsel for the Zong's owners argued that the slaves were killed to save the lives of the remaining captives and the ship's crew and that, therefore, insurance could be claimed on them. Such a claim was at first judicially upheld, but then called into question when it was discovered that some of the murders had taken place after rain had restocked the ship with water.

A great deal has now been written about the place of the Zong in the world of eighteenth-century insurance and the law, and how these related to the slave trade.Footnote 2 There has been much emphasis on commercial calculation in explaining the murders: the Captain's mind, according to Simon Schama, had become “a very abacus of gain and loss” as he chose people to be thrown overboard, thinking that insurance could be claimed on those murdered.Footnote 3 The whole legal and commercial culture of the eighteenth century stands condemned by the fact that the murder of slaves could openly be justified in court, and initially held to be lawful by the Lord Chief Justice.

Arguably, however, it is a medical culture as well that stands condemned by the events. We can see this if we move the focus entirely away from insurance and the law, and bring it to bear on aspects of the slave trade that have largely been ignored in explorations of the Zong massacre. These relate to the medical world of the slave trade, to the process of selecting captives for purchase by the traders on the African coast, and to the fate of those not selected. All of these phenomena were enmeshed with each other and helped to create the context in which the decision to engage in mass murder on the Zong became possible. For the selection of slaves for the transatlantic journey could involve some – pre-eminently, ships’ surgeons – in a chain of murder on the African coast. In this way, a key moment of every slaving voyage, the buying of Africans, might be considered to have habituated slavers to the death of those deemed unfit for the trade, even before the voyage commenced. The atrocity of the Zong is made more comprehensible by this fact.

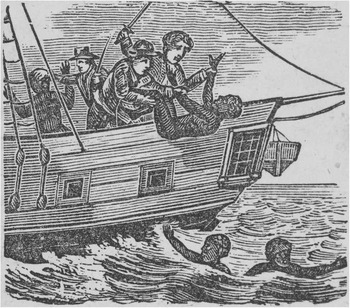

Figure 1 A nineteenth century image of slavers throwing slaves overboard. Engraving from: A. M. (Austa Malinda) French, Slavery in South Carolina and the ex-slaves; or, The Port Royal Mission (New York, 1862), p. 193. Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Used with permission.

As is well known, the slave trade was an enormously complex phenomenon, and there were many ways of becoming a captive for sale. During the period of the Zong in West Africa, the dominant ways were being taken prisoner in war, falling victim to organized raids or kidnapping, being surrendered through indebtedness of various kinds, and being sold because of some presumed violation of the social order/equilibrium of a community. In the actual procurement of captives prior to their being purchased for the Atlantic traffic in people, Europeans tended not to have a direct role, although of course their indirect role in propelling the process through their provision to African traders of credit and an unlimited market for people was vital.

There came to be an increasingly ruthless commercial dynamic impelling African traders in their hunt for people. However, there is also no doubt that often the Atlantic slave trade linked up with various cultural and social practices in African societies that might, in and of themselves, originally have had no link to converting the human being into a commodity. These practices now became enmeshed with this process and they were changed by it. Thus, the widespread practice in West Africa of debtors providing people as “pawns” to creditors to be held until a debt had been made good appears to have been increasingly transformed under the pressure and opportunities of the Atlantic slave trade. It thus became a much more coercive practice on the part of self-proclaimed “creditors” who were now given to the kidnap and sale of people.Footnote 4 Moreover, punishment in West African societies – for example, that meted out to outcasts, to those viewed as politically troublesome, and to those accused of witchcraft or criminality – increasingly came to include sale to European slavers or to African agents who traded with them.Footnote 5

The reasons particular captives were brought to the slave ships – whether for commercial, social or political reasons – were of no interest to the European buyers, who saw them as no more than a potential part of their human cargo. Inclusion in that cargo meant transformation of the captive into a commodity linked up to advanced financial instruments and the complex trade and production flows of a European-dominated order. Social connection and significance had been stripped away from the individual captives. They had suffered what Orlando Patterson has famously called “social death”,Footnote 6 and their fate was then bound up with one significance only: commodity value.

In determining that value through an elaborate selection process, surgeons aboard slavers played a crucial role. If captives were purchased, they would then be held prisoner, stowed, transported and (if they survived) prepared for market. However, if the captives were deemed not good enough to be purchased, the surgeon was in effect denying them value as a commodity. The slave then – if he or she could not be sold elsewhere – underwent what might be termed “commercial death”. And, as we shall see, in the slave trade, commercial death all too often spelled actual death.

THE UNSOLD CAPTIVES: PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS

Let us begin in the era of the Zong, with a skeletal entry in the log of another slave ship, the Unity, from its voyage of 1769–1771. It evidently refers to captives brought on board the vessel by a trader, probably African, who tried unsuccessfully to sell them: “varied [?] Slaves came on board but [we] made no trade”.Footnote 7 These nine words, so characteristic of slavers’ logs in their matter-of-factness, mask a tragedy. We know well enough what would have been the fate of these slaves had they been bought – imprisonment in the cruel world of the slave ship, shipment across the Atlantic and, if they survived, slave labour on a plantation. But they were not bought, their fate remains unspecified, and the historian must therefore provide a context that allows us to imagine what befell these nameless people if they continued to remain unsold to European slavers or, indeed, to Africans. If the captives had much to fear if they were sold, they also had terrors to endure if they were not. For when European slave traders refused to buy particular slaves on the coast of Africa, and no other economic or social use was conceived for them, the captives were frequently killed by their African controllers.

The pattern of killing, or – what amounted to the same thing – of allowing unsold people to die from starvation, would have varied according to differing circumstances, and would have been affected by regional factors and the milieu in which the African traders operated. Of relevance would have been the traders’ access to African buyers of their slaves, the degree to which local African communities could absorb further captives and dependants at a given time; the traders’ ability to sustain the unsold (often dependent upon access to agricultural production in which the unsold could be made to participate); and, finally, the nature of the unsold themselves.Footnote 8 Where such people were considered physically impaired and especially weak (often through age) or socially dangerous (as when accused of witchcraft), they were in a particularly dangerous situation. That many of them were killed or left to die by African merchants who could not sell them was commented upon by contemporaries.

The problem for the historian is that exaggerations of such killings by apologists of the slave trade make the scale of the phenomenon difficult to determine. It was, after all, a common argument of supporters of the slave trade that the European buyers of Africans were actually their saviours: they proposed that captives brought on to the ships would, if left on the African coast, have been put to death.

Thus, Richard Miles, a man who proclaimed himself in 1789 as “considerably concerned in the African Slave trade”, somebody who had himself “bought some hundreds – some thousands of slaves”, warned the British parliament that human sacrifice was extremely common on the Gold Coast of Africa. When slaves did not find European buyers, he argued, “[m]any thousands of them are sacrificed at the burials of great men”. On occasion, he declared, he had actually “given three or four pounds per head for Slaves to save their lives”. When asked by a parliamentary committee if he had “ever heard any conversation pass between the Natives of what would become of any particular prisoners […] not bought by Europeans”, he suggested that the unsold would be subjected to the widespread “custom of sacrificing”. The African merchant, he said, would in almost all instances kill a slave who was not saleable because of poor health or some other reason. And there was even one African leader (“a great monster”), he said, who “took more pleasure in killing his Slaves than in selling them”.Footnote 9 Likewise, Jerome Weuves, a man active in the slave trade when he gave his evidence and someone who could boast of having acted as “Governor of most of the British forts on the Gold Coast”, asserted a belief that unsold slaves were “generally set aside for such sacrifices” as accompanied the demise of prominent men.Footnote 10 The skulls of the murdered, it was said, “paved” certain burial sites.Footnote 11

If we relied entirely on such testimony, we might be led to believe that West African societies were marked by a carnival of slaughter. One must, of course, reject the interested exaggeration of contemporaries, even if one should be careful – as one should be in the analysis of European societies – not to overlook how atrocious particular moments and practices were: in slaveholding African polities, the sacrifice of slaves did take place, and it was a commonplace at the funerals of notables.Footnote 12 Nevertheless, the idea of a general slaughter of anybody who could not be sold to the slave ships runs against the basic facts, since African societies often depended on the absorption of captives for the enhancement of networks of power and patronage. (As is well known, once absorbed in this way some slaves could rise in status over time.) In the long history of the slave trade across the continent, the number of captives forced into African societies is held to have been equivalent to about half the number pressed into the slave ships that plied the Atlantic, and it was actually greater than the total traded in the “Oriental” slave trade from the east coast of the continent.Footnote 13

Even so, in the rapacious process of the capture and absorption or sale of slaves, there were often numbers in excess of those who could be sold in the Atlantic trade or who could be incorporated into African societies. Recent research regarding the Bight of Biafra suggests that African participants in the trade increasingly drew a clear line between those captives for whom a place could be found in their societies and those earmarked for sale and deportation.Footnote 14 There were, after all, limits to the absorption of captives in African society. It could be politically and socially dangerous for the population of slaves to rise above a particular level in a given polity. Paul Lovejoy has even argued that the Atlantic slave trade and “the execution of slaves, criminals and prisoners at state functions” were “methods of controlling the domestic slave-population” in Dahomey.Footnote 15 This brutal fact reminds us that the killing of slaves within West African societies could easily be one side of a brutal coin, on the other side of which was the Atlantic slave trade. This coin was often thrown into the air when captives were brought to the slave ships. Europeans knew this.

We need to bear in mind as well that many of the people captured in war would not or could not be absorbed by victorious polities. The proof of this is that once the Atlantic slave trade diminished, there arose a common practice – at least amongst “the militarized states of Senegambia” – of putting to death prisoners taken in armed conflict: previously, they had been sold to the slavers.Footnote 16 The implication of this is that many prisoners of war during the slave trade itself had the choice of being sold or killed. Moreover, if the people being offered for sale to Europeans were outcasts or accused of witchcraft by their communities, they were only brought to the slavers as an alternative to being killed. If they were not bought, their fate was sealed.

Significantly, one encounters very specific examples of this in the testimony of Europeans who engaged in the slave trade. This suggests that those giving the evidence were drawing on personal experience, even if they sometimes might have placed the facts into a discourse that exaggerated the scale of the killing. Thus, according to that former governor of slave forts on the Gold Coast, people condemned as witches who could not be sold into slavery would be killed. Indeed, he continued, the entire family of the witch would also be “extirpated”. But the argument was not left at a general level; it was illustrated by a very particular memory from his time as Governor of Anamabo, the place – interestingly – from which the Zong sailed on its doomed voyage:

A woman who was accused of Witchcraft, or the wife of a man accused of Witchcraft was brought to me (she was very old) to purchase. – I did not know then that if I refused to purchase her that she would be put to death, I therefore refused her. – She went away with the persons who brought her; and upon being informed by one of my servants that it was the intent of the people in town to cut her head off, I sent a messenger immediately after those people, to say I would take the woman, and give them something for her, rather than she should lose her life; but unfortunately my messenger arrived five minutes too late, and her head was off her shoulders.Footnote 17

Consider, too, the evidence of John Fontain, who had worked for the African Company until 1789. He distilled the wisdom of his experience into a brutally frank phrase regarding the slaves: “if they are not saleable they are put to death”. But, again, his view was particularly influenced by a specific incident regarding a captive of advanced years:

A woman was brought into Cape Coast Castle, to be purchased; who being very old, and very infirm, was rejected […] by the residents, as by the shipping, Dutch, and others – after which, because the Black trader would not be at the expence [sic] of her maintenance, he carried her into the Bush […] where she was murthered, and afterwards found.Footnote 18

In the cases above, it would seem that real incidents were being referred to in the service of propaganda. No doubt, the emphasis on human sacrifice and the killing of those who could not be sold bespoke the slave traders’ defensiveness. The information cited above was, after all, put before parliament in 1789, by which time the abolitionist campaign was casting doubt on the humanity of those engaged in the commerce in human beings. Those benefiting from the slave trade were under pressure to provide a moral justification for their ghastly manner of earning a livelihood. Consequently, they argued that there were only two choices open to the captives: death or to be sold as slaves. The slave trade, its apologists insisted, was saving lives.

When a parliamentary committee asked a witness who had been engaged in the slave trade on the Gold Coast if “the purchase of Slaves by the Europeans” might be held to “contribute to preserving them from being sacrificed, or otherwise put to death”, the answer was forthright: “I certainly do believe that it contributes much”.Footnote 19 Such an argument was even elevated to the divine realm, with some arguing that God might have licensed the slave trade to keep alive myriads who “who would otherwise be put to death”.Footnote 20 One anti-abolitionist tract even went so far as to argue that the abolitionists by their efforts threatened, in effect, “to murder one hundred thousands or more annually”.Footnote 21

However, in clearing away such exaggeration, we must nevertheless accept that the killing of unsold captives was a real and fairly frequent phenomenon. It is supported by specific examples, such as those given above. And it also fits into the context earlier established and recognized by existing scholarship: that is, the limits there were to the number of slaves that could or would be accommodated by African societies; and the fact that there were reasons (for example, accusations of witchcraft) why some people rejected by the slave ships would never be accepted back into the communities from which they came. The next section of this article provides still more compelling evidence of rejected slaves being killed. Precisely because of this, in their decisions of whom to buy and whom not to buy, the European slavers were – already on the African coast – complicit in a process that often resulted in the murder of those deemed to have no place in their project: the delivery of saleable human beings to a market across the Atlantic.

SURGEONS, SELECTION, AND COMMERCIAL DEATH

The killing in Africa of slaves who were viewed as of no commercial value is something that would have been encountered or heard about by experienced men on slaving vessels, particularly by those such as captains or ships' surgeons who were involved in selecting captives for purchase. When African traders brought captives for sale to Europeans, the slaves were – to use the words of one who acted as a ship's surgeon in the 1780s – “minutely inspect[ed]”, and their strength and health assessed:

[…] if they are afflicted with any infirmity, or are deformed, or have bad eyes or teeth; if they are lame, or weak in the joints, or distorted in the back, or of a slender make, or are narrow in the chest; in short, if they have been, or are afflicted in any manner, so as to render them incapable of much labour […] they are rejected.Footnote 22

The slaves’ bodies then were pored over, with a humiliating attention to detail. Here is another eighteenth century surgeon remarking on this aspect of his work:

Sometimes the Men have Gonorrhoeas, or Ulcers in the Rectum, or Fistulas, and the Women Ulcers in the Neck of the Matrix […] you must not be contented that they seem to be in Health, but take good notice of their Eyes, whether the Whites be not of a livid or russet Colour, and the little Veins yellowish or livid, their Eyelids padded, and under their Eyes an unnatural Colour […] or whether their Eyes seem hollow, or sunk[en] […].

Look, too, he advised, for any traces of “pocky Pustles”, and “whether they have no Mark in the Groins, or Ficus's about the Anus, or Marks of Scabs having been about the Scrotum, or Signs of Ulcers having been betwixt their Shoulders”. Mouths and throats were also inspected; pallor was attended to, as also signs of emaciation.

Attention of this kind allowed the surgeon to ensure as best he could that he bought only healthy slaves or, where this was deemed appropriate (that is, when a cure was held to be possible), that he could bargain down the price of captives whose condition suggested to him that they carried a particular disease (“tho the Venom lies hid”). Once it had become clear that the potential buyer had discerned the signs of their latent illness, the African sellers were said to be anxious to dispose of such slaves “at half the Price; nay […] at any Price”.Footnote 23

The surgeon would have to be particularly on the look out for illnesses that were contagious. If he missed them, or if his suspicion that they were present was ignored by his superior, the results could be catastrophic. On one slaver, the Briton, 200 slaves died as smallpox swept through their ranks. The doctor had evidently warned the Captain against buying a particular slave because he was convinced that the captive carried the disease. But the Captain would not be persuaded. It was not long before the illness afflicted “almost all the Slaves in the ship”. One of the crew had clearly never forgotten the horror: “the platforms I have seen”, he remembered, were “just like one continued scab with the matter”.Footnote 24

The surgeon was required to be vigilant in order to prevent such horrors, which were principally viewed by the owners as commercial losses. But it was not merely the possibility that slaves might carry some contagion that was investigated. The slaves being purchased had to be resold in the New World, and the slavers had to take care that they were buying people healthy, strong, and young enough to have a reasonable chance of surviving the rigours and terrors of the Middle Passage, and then of being viewed favourably by the New World planters who would inspect them after the voyage. In the initial choosing of slaves for purchase, then, slavers were already calculating chances of survival, and they were determined to insure themselves against the costly fate of the weak or the ill. Not surprisingly, then, captives were not only scrutinized for signs of sickness, they could also be required “to perform some physical exercise” by the ship's surgeon.Footnote 25 For historians of labour, it is the modernity of such procedures that is striking: medical professionals well into the twentieth century were requiring migrant labourers seeking work in the capitalist societies of western Europe to demonstrate their physical capacity for work.Footnote 26

Rejection was frequent, especially because some of the modes of delivering captives to potential buyers from Europe severely weakened many. From the mid-eighteenth century – indeed for some time before that – most slaves came not from areas close to the coast, but from “far in the interior”.Footnote 27 Maps of the vast African region from which the slaves of the New World were drawn emphasize how far from the littoral slaves could be marched and rowed before they reached the slave ships.Footnote 28 There is still no adequate social history of the impact of this experience on the captives, although the great work of Joseph Miller evokes something of this with respect to Angola.Footnote 29 While we are familiar with the extremities suffered by slaves during the transatlantic Middle Passage, there has been notably less emphasis on what was endured on the journey to the coast prior to purchase and transportation, a journey that could on occasion be astonishingly lengthy.

“Receiv'd on board”, recorded Captain Gamble of the Sandown, then (October 1793) on the West African coast, “5 Men Slaves […] who have travell'd upwards of 1000 Miles”. When, a few months later, he remarked upon the Fula traders “bringing their slaves for Sale to the Europeans” – with the neck of every man being linked by a stick to the waist of the man behind him so that a single overseer could “steer fifty [slaves] and stop them at his pleasure” – he noted again: “They sometimes come upwards of one Thousand Miles out of the interior part of the Country.”Footnote 30 It may be that Captain Gamble was overstating the length of what he clearly felt had been a very lengthy journey, but a long-distance snaking of slaves to the coast was not unusual: a Frenchman employed by the Governor of Senegal in the 1780s referred to “[w]hole chains of captives” brought to various centres after “marches of sixty, seventy, and eighty days”.Footnote 31 And one who had been involved in the slave trade from the coast of what is today Nigeria spoke of people being kidnapped, and trekked for several days to fairs where African traders bought them. There would then be a journey of a few hundred miles to the coastal centres of Bonny and Calabar, where slaves would be sold to the Europeans. Canoes were commonly used to bring captives to market, with days spent in the narrow craft as they made their way along the waterways.Footnote 32

In a sense, then, the Middle Passage began on this journey in Africa itself, so much so that a surgeon to a slaver spoke of the captives having already endured on it something “of those dreadful sufferings which they are doomed in future to undergo”: “even before they […] reach the fairs, great numbers perish from cruel usage, want of food, travelling through inhospitable deserts, &c”. In the canoes that took them to the coast, the captives were forced to lie down, “their hands tied with a kind of willow twigs”, and they were “much exposed to the violent rains which frequently fall”, as also to the water that seeped into the leaky craft.Footnote 33 Bound and supine, inadequately fed, is there any wonder that some arrived at the coast only to be rejected by the Europeans who had assembled to buy them? The whole process by which Africans were moved to the coast was marked by terrors, privations, and brutality. It is now generally accepted that the numbers of captives who died before they reached the ships was greater than the number who died during the Middle Passage itself.Footnote 34

If the African traders – already habituated to the large-scale death of captives in the very process of procuring them and delivering them to the Atlantic – failed to find purchasers for their slaves, the results could be fatal. Indeed, there is some evidence that in holding areas on the coast where captives awaiting sale were held, the merchants might identify those whose condition precluded their sale to the ships and have them drowned.Footnote 35 Abolitionists as well as historians of the slave trade have made clear the brutalization of the Europeans and Americans that resulted from their treatment of other humans as commodities. We clearly need more investigation of its meaning for the practices and sensibilities of the Africans benefiting from the slave trade.

These were people who could be highly attuned to the market in human beings, and they were used to aligning the supply of slaves with the best opportunities for selling them. This is why an official of the African Service based at James Fort, Gambia, could write in 1758 that it was just as well that “very few Ships” had lately come in. There was, at present, he said, “so great a scarcity of Slaves” and he put this down to the African traders “being aware of the few Vessels in the River,” which had led them, he said, to have “kept back their Coffels”.Footnote 36 At around the same time, it was reported from Cape Coast Castle, that “Blacks at Anamaboo” had set a minimum price below which “no one should sell a slave to the Shipping”.Footnote 37

African merchants clearly played a market in slaves, and at certain points this could lead them to have slaves on hand for whom they did not have purchasers. What did choking off the supply of slaves to European buyers imply for the captives? Were all those held back from the market, or for whom a market could not be found, necessarily kept alive? It would appear not. As Joseph Miller has revealed in the Angolan case, the strategy of keeping slaves from the Luanda market in order to drive up the price at which they were sold incurred a human cost: starvation and disease took their toll in the places were the captives were halted and held.Footnote 38

Indeed, when a severe disruption of the slave trade led to a mismatch between the European buyers of people and their African sellers, this could rebound catastrophically on the slaves. John Matthews, a naval lieutenant based in Sierra Leone, wrote in 1787 that: “During the late war in which England was engaged with France, when the ships did not visit the coast as usual, and there were no goods to purchase the slaves which were brought down, the black merchants suffered many of them to perish for want of food.”

Now it is true that this was written by one who supported the slave trade, and who therefore might be given to implying that the European purchasers were the saviours of the captives: he went on to assert that the African traders had told him that, with the arrival of the slave ships now in question, “the inland people” would “cut their [slaves’] throats, as they used to do before white men came to their country”.Footnote 39 But Matthews’s observation about the starvation of many slaves who could not be sold surely lies within the logic of the traders’ enterprise. They viewed the captives brought to the coast overwhelmingly as the means by which to acquire European goods. If they could not be used in such acquisition, if they could not be sold off in domestic markets, what was their purpose? Why expend further resources on keeping alive people for whom they had no further use? It may be that at this point many African merchants decided whom it was worth keeping alive – such as those who would be viewed most favourably by Europeans should slaving vessels appear, or those whom they felt they could keep for some future purpose. For such people, a more adequate means of sustenance might be provided; for the other captives, little or nothing. They could die.

In this regard, the testimony of Thomas Aubrey, a ship's surgeon of considerable experience on the coast of West Africa, is of importance. In 1729, he published his treatise, The Sea-Surgeon, or the Guinea Man's Vade Mecum: its sub-title referred to “The Best Way of Treating Negroes, both in Health and in Sickness”. Given its date of publication, we may confidently assert the author's lack of involvement in any of the debates regarding the slave trade. 1729 was over half a century before the campaign to abolish the slave trade commenced in earnest. Consequently, what Aubrey had to say about the relations between African traders and their captives had no partisan function. But his view nevertheless was that “if they don't sell them, they will surely starve them to Death”.Footnote 40 There were many instances of this and the whites engaged in the slave trade were aware of the phenomenon. They were also aware of other extremities that could befall the captives if, after having been “carefully examined” for any “blemish or defect”,Footnote 41 the Europeans decided not to buy them. For what did rejection mean for the slaves? It might mean the African trader holding on to them in the hope of selling them to another ship, or getting something for the captive from a local community. But it could mean starvation, as suggested by Aubrey, who had been referring specifically to slaves whose illness precluded their sale, Footnote 42or perhaps some other brutal fate.

It was reported by one ship's surgeon that the African merchants, disappointed by their failure to sell the rejected captives, “frequently beat those negroes”. Whatever the cause for their rejection – “age, illness, deformity, or for any other reason” – they were treated “with great severity”. And at one of the major slave marketing centres, the African traders’ response was truly atrocious.

At New Calibar […] the traders have frequently been known to put them to death. Instances have happened at that place, that the traders, when any of their negroes have been objected to, have dropped their canoes under the stern of the vessel, and instantly beheaded them, in the sight of the captain.Footnote 43

Three factors give this testimony credence. Firstly, it comes from one who had been intimately involved in the slave trade but who had come to oppose it. (That opponents and supporters of the trade – though for diametrically-opposed purposes – should both have emphasized the cruelty visited upon unsold captives points to the fact of its existence.) Second, it chimes with what scholarship has established about decapitation in West Africa. This was, for example, a common fate for defeated enemies on the Slave Coast, and it could vie with the fate of being sold into slavery by victorious Africans.Footnote 44 Third, it is supported by other evidence in which one may have confidence. The naval gunner Henry Ellison, who had worked in the slave trade from 1759 to 1770, recalled many years later a shocking incident. An African notable known as Captain Lemma Lemma had arranged for three African captives – “an old man, a young man, and a woman” – to be taken on to the slaver on which Ellison worked:

Mr. Wilson, the chief mate, purchased the young man and woman; the other was too old, and he refused to buy him: Lemma Lemma then ordered him (the old man) into the canoe, and his head was laid upon one of the thwarts of the boat, and chopped off, and immediately thrown overboard.Footnote 45

No doubt a particularly weak social connection between the trader and the rejected slave – for example, if the slave had originally been captured through a raid upon a distant community – might allow such a brutal response: the victim referred to above was said to have come “a great distance from his [Lemma Lemma's] country”.Footnote 46 But, given that the vast majority of the people sold were not from the communities of the merchants selling them, we must concede that the space for a market-driven brutality against the unsold was great. And one can certainly cite evidence of how even a kidnapped child could literally be hawked from ship to ship and then be threatened with the direst fate when it appeared that nobody might buy him. The naval officer Sir George Young, who had served on the West African coast for substantial periods in the late 1760s and early 1770s, spoke of

[…] a beautiful infant boy, brought along-side the ship in a canoe, for the purpose of sale; having been along-side of all the trading ships, and not able to sell it there, they brought it to the Phoenix [presumably a vessel of the Royal Navy], the ship I belonged to, and threatened to toss it overboard if no one purchased it […]. I then purchased the infant for a quarter calk of Vidonia wine, and brought him to England, and gave him to Lord Shelburne […].Footnote 47

For our purposes, the important point to bear in mind is that, in the buying process, it was “the particular province of the surgeon to examine the slaves”.Footnote 48 Luke Collingwood, until his fateful voyage on the Zong, which was the first (and only) time he acted as master, had been a ship's surgeon and had made frequent trips between West Africa and the West Indies in that capacity. The route to captaining a slaving vessel did not usually pass through the station of ship's surgeon, but this was not unknown.Footnote 49 Indeed, when the British parliament came in 1788 to set down in law the experience that would qualify a man to captain a slaver, it included in its criteria his already having “served as chief mate or surgeon during the whole of two voyages”.Footnote 50 Luke Collingwood was such a man, or rather more than such a man: he had acted as ship's surgeon on “9 or 10 or 11 Voyages”.Footnote 51 This had been his career prior to the voyage of 1781, and it must have affected his whole approach to his work as captain.

Like other highly experienced surgeons in the slave trade, Collingwood would have been aware of the sometimes ghastly fate of those slaves whom he failed to select for purchase. As has been demonstrated, the decision of the surgeon to reject a particular captive could be a sentence of death. If moral scruple could not be allowed at that point to trump commercial consideration, one can see how the surgeon (or the captain who had been a surgeon, as Collingwood had been) could already be implicated in a process of selecting people for murder. What remains striking about the role of the surgeon at this point is that, even when he evinced a high degree of concern for the slaves at sea – indeed, he could be horrified by their brutal treatment on the voyage – he would have no compunctions about participation in an initial selection which might, as he knew, condemn some people to death.

Thus, the ship's surgeon Thomas Aubrey recorded his anguish at the cruelty shown slaves during the Middle Passage: “my Heart hath been ready to bleed for those poor Wretches, when they have been so treated; and I have also saved many a Hundred (by God's Assistance) both from Abuse and Death”. He also publicly excoriated particular actions on the ship which led to the unnecessary death of slaves, and was unequivocal in his moral condemnation of those responsible: “It's Inhumanity, Barbarity, and the greatest of Cruelty of their Commander, and his Crew, together with either Ignorance of the Surgeon, or his downright Cowardice, in not daring to advise his Commander better.” And yet this ship's surgeon in the same publication of 1729 advised prospective surgeons in the trade to exercise great stringency in the choice of captives for purchase. This, he suggested, was fundamental both to the standing of the surgeon as also to the profit of those financing the enterprise. The stricture was delivered on the very same page on which Aubrey insisted on fatal consequences for unsold captives.Footnote 52

A MEDICAL ROAD TO MURDER ON THE ZONG?

The captain and the ship's surgeon, then – and Collingwood was probably both on the Zong, given that the crew was so small – could quite easily and knowingly shake hands with murder before the ship sailed with its human cargo. And death shipped out with them, too. The slaves were placed in conditions that were guaranteed to result in death for substantial numbers. Especially before parliament had compelled the slavers to improve conditions during the Middle Passage – this was some years after the Zong's infamous voyage – the death rate was sufficiently high to ensure a steady heaving of African corpses off the ships and into the seas. This was so even when a voyage had, in relative terms, a low mortality rate.

Consider the case of the slave ship Unity which undertook the Middle Passage in 1770 with 425 slaves on board. Just over 1 out of every 30 of them died during the two-month voyage between Sao Tome and Jamaica.Footnote 53 (For a British slave ship in the latter half of the eighteenth century, this would have been considered a low death rate, since in this period just over 1 in 10 slaves perished aboard the British ships taking them to the plantation colonies.)Footnote 54 On 7 June 1770, the Captain of the Unity wrote that the slaves were “pritty healthy”, and yet, despite this, he was soon routinely noting the demise of captives: “Died a Girl slave No. 9” (13 June); “Died a Woman No: 10” (14 June); “Died a man slave No. 11 (15 June); “Died a woman Slave No. 12th” (16 June)’. The list could be extended with entries from the last week of June and the first fortnight of July, 1770.Footnote 55 In the conditions of the slave ship, then, the death of African captives was a commonplace even on a “good” voyage when the slaves had been judged “pritty healthy”. But, of course, the Zong was on no ordinary voyage.

Virtually all slave ships, with their terrible overcrowding and woefully inadequate ventilation and sanitation, created the conditions for epidemics. This is why measures had constantly to be taken to counter the in-built tendency towards the spread of disease on the ships. Hence, every day the slaves would be taken on deck where they could breathe the fresh air and be forced to exercise, with the cat-o-nine tails in effect beating time if they were reluctant to “dance”. While they did this, seamen would clean their quarters, dispose of the excrement, scrub and scrape the platforms, sometimes using vinegar to wash the area below decks, which could also be smoked.Footnote 56 This was hard, unremitting labour that would end only when the Middle Passage was crossed. It was partly because of this labour process around the maintenance of the slaves’ health that so many crew members were required. (Crews on slavers were larger than those on any other commercial vessel.Footnote 57 Aside from the work of operating the vessel itself and the intensity of the labour of tending the slaves, crew members had to serve as warders of the captives and, of course, as guards against insurrection.)Footnote 58 But here was the problem for the Zong. It was seriously undermanned. The Zong carried 442 slaves and was crewed by only 17 men.Footnote 59 This ratio of crew to slaves, 1 to 26, was unusually low.

As the voyage lengthened far beyond what was the standard, the labour of tending and controlling the slaves as well as maintaining basic conditions of hygiene may well have become impossible for the crew, especially as the Zong pressed its captives into an area beneath the deck which was so grossly inadequate for their numbers that it stands out even in the slave trade: under the Dolben Act of 1788 by which the slave trade was regulated, a ship of the Zong's tonnage would have only been allowed to carry 175 slaves;Footnote 60 when it sailed, it was carrying two and half times this number.

By the time the ship missed Jamaica owing to the Captain's navigational error, there was clearly an epidemic aboard the ship: more than sixty slaves had died by this time and, if we concede a correlation between serious illness and those who were to be drowned, twice this number may have been seriously in the grip of a viral dysentry.Footnote 61 The ship was now weeks from Jamaica and an experienced ship's surgeon like Collingwood would have known that deaths from dysentery tended to mark particularly the last weeks of a voyage.Footnote 62 Moreover, what did the Captain and the surgeon – Collingwood was both – see when he looked at people who were seriously ill? If such people had been brought to him on the African coast, they would already have looked to him like ghosts, people who were to be rejected for purchase and left to the sometimes murderous fate decided for them by their African controllers. The seriously ill slave was a rejected slave and (as would have been known) a dead slave. Why should it be different now?

Historians have tended to pass over the significance of Collingwood's medical role in the slave trade and its relationship to the massacre that he ordered.Footnote 63 But the fact that Collingwood was a surgeon should be wrung for all its significance. For, once an epidemic seized hold of a ship, the seriously ill slave became a problem for a number of reasons, in which the medical was inextricably linked with the commercial. Firstly, it became ever less likely that the slave could be sold at market. Secondly, making such a person well required much labour and resources which then diminished what the ship held to sustain others: the standard epidemic on the slave ship, the flux (or dysentery), required that its victims – if they were to have a chance of recovery – be given enormous quantities of water (precisely what the Zong lacked) to replace the liquid convulsed out of their bodies by the disease.Footnote 64 But the seriously ill were also viewed as dangerous because they could spread infection to others, including the crew. They were thus inevitably viewed as a threat to the lives of those who were still well, as also to the commercial viability of the enterprise as a whole. At a certain point, moreover, it would appear that they were viewed as corpses. One doctor who had served as a ship's surgeon on a slaver and who had since become an abolitionist admitted that “once the fever and dysentery get to any height at sea, a cure is scarcely ever effected”.Footnote 65

It can be seen that such a view, in the desperate circumstances in which the Zong was in 1781, could move into the dark zone: a cure is unlikely; can death be hastened? This was a question to which the surgeon-captain subject to the logic of a slave ship – especially one unsure of its water supplies, and beating against the wind to a destination it had missed – was likely to answer in a particular way.

While it is important to note the findings of Richard Sheridan – that some fine physicians took part in the slave trade and, moreover, that there are examples of surgeons clashing with the captains over the treatment (medical and otherwise) of slavesFootnote 66 – it is equally important to recall that the extreme environment of the slave ship was conducive to sinister actions taken either on a medical basis, or in the course of medical work. One gets a sense of this from the testimony of the gunner James Morley, a man who had extensive experience aboard slavers in the 1760s and 1770s. He spoke of the frighteningly brutal anger of “the surgeon's mates” as they forcibly dispensed medicines to slaves, using a pannikin to lever a passage into the mouth, cursing and beating the slaves, more than half the medicine being lost in the process:

[…] this was done when the poor wretches have been wallowing or fitting in their blood or excrements, hardly having life […]. I do declare, that I have known the doctor's mate report a Slave dead, and have him thrown over-board, when there has been life in him, and he has struggled in the water after being thrown over-board; this I saw; and why they did this, not one on board could imagine, only to get clear of the trouble; that was the conjecture of them that saw it.Footnote 67

This gives us a good sense of how the slave trade could corrupt medical work, but perhaps of more significance for the argument advanced here is the evidence of Charles Wadstrom, who was part of an official Swedish expedition to West Africa in 1787–1788. He was adamant that a few masters of French slavers had unequivocally told him in Goree [Goreé] that they kept a stock of poison aboard their ships for use against slaves when “contagious sickness” took hold.Footnote 68 And we have an example of the deliberate putting to death of a slave aboard a ship when it was feared that the smallpox that she carried would be communicated to others.Footnote 69 Joseph Miller has uncovered evidence of a similar nature in the Portuguese slave trade.Footnote 70

If slaves could be compared to livestock – the greatest of the Lord Chief Justices of eighteenth-century England considered them akin to horses in legal terms for certain purposes;Footnote 71 the way they were inspected by buyers, likewise, was compared to the scrutiny of a horse for purchase and one can find them referred to as “black cattle”Footnote 72 – then perhaps a standard mode of containing disease amongst domesticated animals (that is, slaughter) could occasionally be used against them.

It may be true that the murderous solution on a mass scale was undertaken only in exceptional circumstances: the slavers, in the main, were trying to bring living people to market. But we should not let the exceptional circumstances obscure the links and routine behaviours that have been established in this article. Selection of slaves for purchase entailed rejection of others on a medical basis that could result in their murder by African traders in the full knowledge of the selectors, amongst whom the surgeons were prominent. Once on the ship, circumstantial and some direct evidence suggests that the containing of epidemics did lead to some murders and, perhaps, what could be described as the hastening of death in a quarantined area.

Many years ago, it was demonstrated that one of the roads to Nazi mass murder ran from the “euthanasia programme”: a distorted and brutal medical logic could habituate people who had engaged in the killing of the “unfit” to mass killing.Footnote 73 We need to ask if Captain Collingwood's long service as a slave-ship's surgeon with all that that entailed – the momentous decisions regarding who was unfit for plantation slavery and thereby left to the mercies of the African traders; the cruelties of “managing” health and containing epidemic aboard the slave ship – had somehow prepared him for the act of mass murder that he ordered.