INTRODUCTION: CARCERAL CONNECTIONS

Although the course of history is often portrayed as one in which modernization and, more recently, globalization have propelled the world forward on a path of increasing freedom, the impact of historical lines of coercive, incarcerating, and disciplining strategies cannot be ignored. It can even be argued that coercion and incarceration are not diminishing, but are one of the trends affecting labour relations in a globalizing world, alongside those of increasing wage labour, growing precariousness, and the declining power of labour organizations.Footnote 1 In any attempt to understand these “long” lines, or “deep” histories, of practices of coercion and incarceration, the colonial links are key. In the crucial and transformative colonial era, European imperial projects deeply impacted societies in South and South East Asia, changing them from often developed and sometimes market-oriented societies into colonial societies marked by state-directed bonded and tributary labour regimes. This not only brings together the histories of Europe and Asia – which are all too often studied in a disconnected fashion – but also brings to light the interconnections between histories of coercion, incarceration, and exploitation. Shifting the perspective to that of the colonies, therefore, means more than shifting the centre of attention in an attempt to chart lesser studied terrain, or to provincialize Europe. It is a crucial step in understanding some of the major global linkages and processes behind the transformation of the modern world.

This article aims to contribute to shifting this perspective by studying the operation of the carceral system in the Dutch East Indies. It indicates, firstly, that the development of different labour relations that were coerced (convict and slave labour) or marked by strong coercive elements (corvée and contract labour) was interrelated. Secondly, it argues that there were deep links between the penal system and wider regimes of colonial-administrative and labour control. Combined, these two different carceral connections underpinned the colonial system and were crucial for accelerating the mobilization of coerced convict labour in the second half of the nineteenth century. This was no coincidence, as the second half of this article shows. The system was geared towards the employment of convict labour in vital parts of the colonial economy. We go on to emphasize the pivotal function of the penal system in the wider colonial project, but also the entanglement of colonial regimes of production and control.

The historiography of convict labour and convict transportation is well developed. Convict transportations from Britain to North America and to Australia have received the most attention among scholars, although interest has now shifted to the Indian Ocean and other parts of the British Empire.Footnote 2 In the case of the Dutch Empire in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the historiography is much less rich. Whereas we now have an extensive literature on the history of colonial labour systems, the penal system has mainly been studied through specific elements, such as the police system, punishment, and prisons.Footnote 3

The wider functioning of the Dutch colonial penal system remains understudied. In her study of the notorious Ombilin coal mines, Erwiza Erman touched on some of the local dynamics of convict labour.Footnote 4 In an overview dealing with the decline of slavery, Anthony Reid observed both the persistent character of the corvée labour system and the increasing importance of convict labour. Contrasting the use of convicts with that of corvée workers and slaves, who “could not be sent far from home”, he argued that “the Netherlands Indian government made use of convicts” “to open up the frontiers of the colony”. In the process, convicts “became overwhelmingly dominant as a form of punishment for every type of crime”.Footnote 5 Reid’s observations aptly capture the importance and strategic use of convict labour but leave under-examined the vital link between the penal system and the wider colonial disciplinary and coercive labour regimes.

FROM SLAVERY TO CORVÉE AND CONVICT LABOUR

It is crucial to note two characteristics of the Dutch colonial penal system. First, the Dutch colonial penal system was not based on the export of convicts from the metropole to the colony. The flows from the Netherlands to the colonies, and vice versa, were minimal. Most convicts were from the colonies, and remained there. Within the colony, long distance and local circuits existed side by side. Second, the Dutch colonial case does not indicate a clear or linear development towards the imprisonment of convicts in rehabilitative prisons. Although the worksites where convicts were placed were increasingly labelled “prisons” (gevangenissen), most convicts were employed at “extramural” convict labour sites, especially in mines, and on infrastructural or military projects.

Figure 1 Forced labourers at work repairing a railway line for the Aceh tram at Meureudu on the stretch from Sigli to Samalanga. 1905. KITLV 90437. Creative Commons CC-BY License.

This system evolved from largely pre-existing patterns developed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries by the Dutch East India Company (VOC). The VOC employed convicts for hard labour in various urban public works and on five convict islands: Onrust and Edam (near Batavia), Rosingain (Banda), Robben Island (Cape of Good Hope), and Allelande (Tuticorin). On the islands, convicts were employed at the wharf, the rope factory, or in collecting limestone, shells, or wood. The urban public works (gemeene werken) consisted of convict quarters (kettinggangerskwartier) from where convicts were sent out mainly to work on infrastructure (roads, canals) and fortifications.Footnote 6 This system remained in place after the VOC’s possessions had been assumed by the Dutch state (1815) following an intermediate period of British rule. Power was only effectively transferred after April 1816.

Patterns of incarceration and use of convict labour changed only gradually, corresponding to the evolving strategies of colonial exploitation in the nineteen and twentieth centuries. In the first few decades of its existence, the new colonial state further developed a refined system of mobilization of labour through compulsory labour services (herendiensten) in combination with the compulsory cultivation of market crops (cultuurstelsel). This entailed large-scale corvée by local populations, employed for plantation work, infrastructure, and public services. The simultaneous increase in corvée and convict labour was not coincidental. These forms of coerced labour were deeply connected, and their rise was related to the changing landscape of possibilities available to the colonial state in employing labour.

Here we encounter our first carceral connection. The abolition of the slave trade stimulated the search for alternative forms of cheap and controllable labour. The expansion and intensification of corvée labour systems was a response to the rising labour demands brought about by the colonial aim of maximizing the commercial exploitation of the colony. The growing use of convict labour in places such as Banda and Banka was linked to this combination of exploitative aims and the limited scope to employ slave labour in a similar fashion. Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, slaves had been an important part of the workforce in the same places in which convicts were later employed. Convicts were sent to replace slaves, but also to replace other labourers in mines (Banka; Padang), on urban public works (Batavia; Semarang), and on plantations (Banda; Java).

As early as 1819, the Resident of Banka “proposed to send 300 to 400 kettinggangers from Java to here, in order to be able to discharge the Chinese workers”. He suggested that “if such a number of convicts were not readily available”, “the convicts who are destined for Banda” should be sent to Banka.Footnote 7 As late as 1837, reports from colonial administrators were still considering “the possibility to transfer 400 Balinese [enslaved] women for the landsperken on Banda”, but such plans were abandoned as being incompatible with the ban on the trade in slaves.Footnote 8 Contract workers and convicts took their place. By the mid-nineteenth century, it was reported that “the number of banished, who are placed in the gardens as well as on other works, present at Banda-Neira, is replenished yearly through the supply from Java. This number should normally be 1,500 to 1,600 heads, but in 1845 it was merely 1,387 men, with 400 women and children”.Footnote 9

COLONIAL LAW AND COERCIVE LABOUR REGIMES

The second carceral connection lies hidden in the mechanisms developed to secure public order and control labour through the local administration of justice. To explain this, it is important to first highlight the colonial legal system in relation to the control of colonial labour. The colonial judicial system in the Dutch East Indies consisted of a range of courts, varying from the Raad van Justitie (High Court of Justice) in Batavia to local courts of justice (for Europeans), and landraden, police judges, and local courts (for colonial subjects).Footnote 10 Only the most serious criminal cases, such as murder or major theft, punishable by longer sentences, were dealt with by the criminal courts. All “minor” offences and other crimes were dealt with under the politierol. This police or magistrate law was executed by local colonial officials without extensive legal procedures, and dealt especially with labour, mobility, and public order offences.

Administrative (or police) law became pivotal in expanding colonial control and coercive colonial labour mobilization. On Java, the foundations for these dynamics were established in the eighteenth century when greater VOC interference, especially in Preanger (West Java), led to increasing demands for the local population to supply market crops, especially coffee and indigo. The local population performed herendiensten for their own leaders, but were now frequently deployed by the VOC to work on plantations, infrastructure, and transportation. The VOC claimed that these were a continuation of pre-VOC traditions, but duties seem to have intensified. In response to the increasing number of “desertions” – people evading corvée obligations by fleeing to other areas – new regulations were implemented to bind local populations more directly to local heads of districts (1728) and to criminalize refusal to comply with the compulsory delivery of produce and goods. The VOC was unable to completely effectuate these regulations and increased the severity of the punishment meted out to “deserters” in the second half of the eighteenth century (1778) to include physical punishment and, for a repeat offence, convict labour “in chains” for six months.Footnote 11

This mechanism accelerated under Dutch state colonialism. Herendiensten were further intensified from the early nineteenth century onwards and extended to entire districts. Corvée labourers were employed in constructing infrastructure (roads, canals, bridges, buildings), in transport (goods, post, and personnel), in maintenance and service activities (demanded by local colonial officials), but also in local community services (cleaning, policing, watching over plantations).Footnote 12 Similar rules existed for the owners of “private land”, although the state explicitly preserved its rights over the corvée obligations of local populations as well.Footnote 13 Despite increasing anti-colonial criticism and the abolition of the cultuurstelsel in the second half of the nineteenth century, these herendiensten would remain an important phenomenon throughout the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century. They were slowly abolished for Java and Madura in the early twentieth century, but were continued in the Outer Districts right until the end of the colonial period. In the 1880s and 1890s, a large proportion of the population of Java and Madura, roughly some three million people, were still obliged to perform these services, sometimes even up to fifty-two days a year. The total number of days’ compulsory service slowly declined, but it was still some twenty million on Java and Madura in 1895.Footnote 14 It was not until the 1920s that it became possible to substitute monetary taxation for corvée labour.Footnote 15

Simultaneously, the nineteenth century witnessed increasing labour mobilization through the use of contracts. The restrictive elements of labour contracts were obvious in the special “penal laws on coolie contracts”, issued for Sumatra from the 1870s onwards to safeguard the fulfilment of labour contracts, criminalizing the labour offences committed by “coolies”. However, in the “regular” labour contracts that were in use, especially on Java and much earlier on Madura, similar criminalizing restrictions bound workers to their contracts and turned mobility (or “exit”) into a punishable offence. The regulations relating to “private land” in West Java drafted in the early nineteenth century provided a means to ensure that “hirelings”, who were employed for more than three months, were registered by the landowner with the local authorities. Their contracts were limited to three years, but renewal was possible after registration. The regulations intended to ensure that contract workers signed “freely”, but also dictated that “local authorities were to closely inspect” whether

workers or hirelings, in turn, perform all to which they have committed themselves, making sure that when they are in breach of this, desert or evade their duties, either due to excessive laziness or unwillingness, they will be punished in accordance with the nature of the matter and in accordance with existing laws and regulations.Footnote 16

This was exactly what created a connection between corvée labour, contract labour, and the practice of magistrate (or police) law. Corvée duties were performed partly through compulsory participation in local policing, watch and patrol tasks, and through taking care of security and order in the villages and on the lands.Footnote 17 In addition to a whole range of social (and increasingly political) issues for which the local police were employed, this explicitly included inspecting and enforcing compliance with the herendiensten as well as with labour contracts, both the general contracts (often referred to as “free”) as well as the “coolie” contracts (non-compliance with which could lead to penal sanctions).Footnote 18 In 1836, the regulations stated that the local authorities in West Java, to which police matters were reported, were authorized to

inspect and decide without any higher authority all matters of crime or offence, and breach of the rules decided in the present regulation [for private lands], and, whenever there are no special sanctions, to sanction Europeans, their descendants, or equals with a fine of up to fifty guilders, or imprisonment of up to eight days; and a native or equal with a) a fine of up twenty-five guilders; b) imprisonment of up to fourteen days; c) punishment by being beaten with a rattan stick, up to a maximum of twenty-five strokes; d) employment on public works, for up to three months, without chains, for one’s livelihood, but without a wage.Footnote 19

THE CARCERAL COLONY

The arrangements could vary from region to region, and they changed over time. However, in general, “minor” offences and crimes were dealt with at the local level under the politierol –police law.Footnote 20 These “minor” offences and crimes included those relating to labour regulations (and restrictions) for contract workers, workers subject to coolie laws, and corvée workers. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the cases trialled under the politierol were recorded in the colonial judicial statistics as magistraatsrecht (magistrate law). Governors, assistant governors, and district heads were empowered to judge minor crimes and offences under the politierol.Footnote 21 These locally administered sentences led to ever growing numbers of convicts serving short-term sentences for minor, more often labour-related offences. The form of convict labour referred to as tenarbeidstelling (being put to work) was the most frequently used sentence for these short-term convictions, ranging from a few days to three months.

At the level of the criminal courts, such as the landraden and Raad van Justitie, sentences were of longer duration. Here, the main type of punishment was mid- to long-term convict labour, which could be either in or outside the district, and with or without chains. Convicts sentenced to forced labour for more than three months were not registered under tenarbeidstelling (short-term convict labour), but under dwangarbeid (long-term convict labour). Their numbers were included in the prison population, while the short-term convicts seem not to have been included in these statistics.

The distinction between short-term local or regional punishment and long-term punishment with the possibility of long-distance displacement would remain until the end of the colonial period. In 1946, Jonkers’ handbook on Dutch East Indies criminal law explained that “the prime difference between a prison sentence [gevangenisstraf] and detention [hechtenis] was that the prisoner could be sent everywhere to serve his punishment, while the detained does not have to serve against his will outside the district in which he resided at the time the punishment is executed”. In this context, the detained included individuals convicted under police law – for “culpable crimes and offences” – but also those detained while awaiting trial.Footnote 22 The essence of all forms of colonial punishment, however, remained convict labour. The handbook further noted that everyone “sentenced to prison or to detention could be compelled to perform labour both inside and outside the walls”. The number of hours to be worked was nine hours per day for prisoners and eight hours for those detained. The “nature of the labour” was to be organized by the Director of Justice. Convicts would “receive monetary reward only for the work performed in excess of the number of hours per day they were required to work”.Footnote 23

The nineteenth and twentieth centuries witnessed a remarkable rise in the number of long-term convicts in the Dutch East Indies, with the average population “in prison” growing from 10,000 in 1870 to 57,000 in 1920.Footnote 24 This was preceded by a much larger growth in the number of sentences for short-term convict labour (tenarbeidstelling) under the politierol. The final decades of the nineteenth century witnessed a rapid rise in the number of such sentences – from 69,500 per annum in 1870 to 275,000 per annum in 1900.Footnote 25

In part, this can be explained as an effect of the abolition in 1866 of the rotanstraf – a punishment that involved being whipped with a rattan or bamboo stick.Footnote 26 The relationship between the sharp rise in short-term convict labour and the abolition of whipping as a formal punishment was also noted in the colonial press, and it effects were debated.Footnote 27 On Java and Madura, however, another important factor may have been the slowly diminishing labour output provided by herendiensten. Although the size of the population on Java and Madura tied to such obligations grew from 9.6 million in 1886 to 11.1 million in 1895, the total number of days deployed in corvée services declined from 26.4 million per annum in 1886 to 20.6 million in 1895. These statistics provide only a limited perspective on the effects of centralized colonial attempts to restore the role of corvée labour. They should also be used with care as they exclude compulsory local municipal labour services.Footnote 28 As the formal supply of corvée labour slowly declined, and whipping simultaneously disappeared as a means to ensure the mobilization and discipline of corvée workers, “administrative” punishments gained importance (Table 1).

Table 1 Convict labour sentences and prison population, 1870–1930.

Figures based on ClioInfra (www.clio-infra.eu); Verslag van de statistiek der rechtsbedeeling in Nederlandsch-Indië over de jaren 1881 en 1882 (Batavia, 1885); Koloniaal verslag 1875, 1886, 1889 (The Hague, 1875/1886/1889); “De rottingstraf”, De locomotief, p. 1; “Verspreide Indische berichten. Indische gevangenissen”, Algemeen Handelsblad, p. 2; “Preventieve hechtenis in Indië”, De locomotief, p. 9; Soerabaijasch handelsblad, 22 March 1906, p. 17.

The relationship between the two coercive labour regimes – corvée and convict labour – was explicitly noted in the early twentieth-century colonial press, for example by the writer of a critique in the Java-bode, who remarked that “the number detained in prisons usually comprises roughly half to three-quarters of punished conscripted corvée workers”.Footnote 29 The observation was part of a complaint that, in many cases, evasion of corvée labour was not punished severely enough by local colonial officials, “the dereliction of twenty days of corvée labour being punished with two or three days of convict labour”. This left private landowners, who claimed the local population for their corvée labour, without sufficient means to enforce the corvée and led to conflicts between private landowners and colonial officials.Footnote 30

EMPLOYING CONVICT LABOUR

The Dutch colonial-carceral system had not only a disciplinary role in relation to other coercive or coerced colonial labour regimes, it also had a pivotal function in the wider colonial project and in the regime of production itself. Convicts were employed with the intention to maximize the use of their labour and minimize their costs. As early as 1828, it had been proclaimed as “the express will of the king that forced labour should as far as possible replace all other punishments, so that the state could make use of the labour of the criminals”.Footnote 31 And as late as 1905, the Director of Justice was still instructing colonial officials that “it was of the utmost importance to choose work that leads to the highest possible monetary benefit in order to compensate for the costs of housing, control, and food of the prisoners as much as possible”.Footnote 32 From this perspective, it was not surprising that convicts were employed in vital sectors of the colonial project (Table 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 2 Accommodation in the Bengkulu residence at Seluma for herendienst conscripts from Aer Priokan. 1920. KITLV 32353. Creative Commons CC-BY License.

Table 2 Overview of places of employment of convicts, Dutch East Indies, 1816–1942.

*Not all expeditions are listed.

**In later periods, convicts on the island of Banka might have been employed to work on infrastructure and general services instead of mining.

***Uncertain.

The placement of convict workers to some extent followed the division between convicts subject to tenarbeidstelling with short sentences, and convicts subject to dwangarbeid with longer sentences. There was, however, much flexibility in employing convicts on sentences of medium duration (ranging roughly from several weeks to eighteen months). As districts were large, the limitation that convicts serving short-term sentences were to be placed on worksites within the district did not exclude the possibility of movement over significant distances. The different groups of convicts were employed in a range of activities related to colonial expansion, infrastructure, extraction, and production.

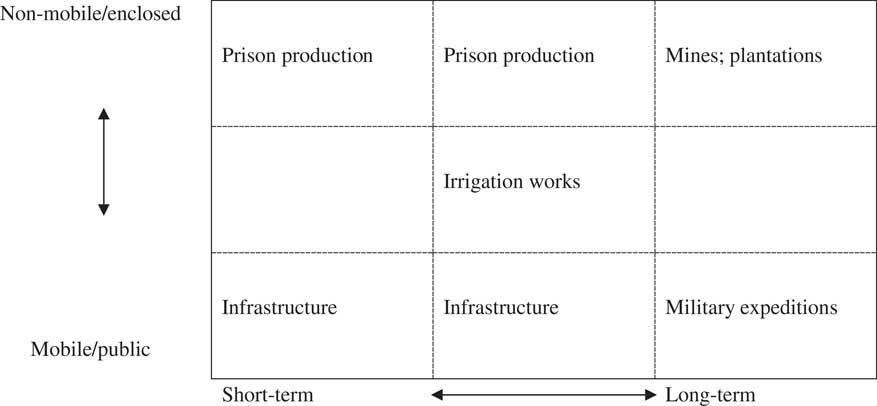

Extractive activities were performed mainly by long-term convicts at more isolated sites, such as mines and agricultural colonies. Activities related to colonial expansion, especially military and geological expeditions, were often highly mobile and public. These, too, however, were mainly the domain of hardened long-term convicts. Convicts serving short- or mid-term sentences were used for other purposes. Some activities were also highly mobile and public, such as work on road and railway construction. Other activities, for example road and waterway maintenance in and near urban regions, could be marked by less mobility, but they were outdoors and sometimes public. The labour on irrigation works was often performed in more outlying agricultural or developing regions. The rise of productive prison environments from the late nineteenth century onwards supplemented this landscape with productive activities in more or less isolated or enclosed environments, performed mainly by convicts serving short- or mid-term sentences.

Figure 3 Role and characteristics of convict labour sites, Dutch East Indies.

Most local, short-term convicts were housed in so-called kettinggangerskwartieren. These were quarters where convicts were kept while not at work. Such convict quarters existed throughout the Dutch East Indies, often located in the middle of urban settlements, and sometimes dating back to the kettinggangerskwartieren of the VOC period (in Batavia and Semarang, for example). These quarters could also be located in more remote areas. Some were built later in the nineteenth and twentieth century. In Ujung Kulon, the most easterly part of Java, for example, the lighthouse had quarters for convicts and an overseer’s house.Footnote 33 In 1882, four building contractors signed up for the open competition for the construction of a kettinggangerskwartier in Probolinggo with a capacity to house 600 convicts.Footnote 34 While in 1929, a dwangarbeiderskwartier (forced labourers’ quarters) for 400 convicts was built near Sangiang (Bali) for their work on the Negara-Tjandi Kasoema-Gilimanoek road.Footnote 35

Convicts were employed on a range of tasks. One of the most well-known and visible was road maintenance, famously referred to as krakallen, but convicts also performed other kinds of public work. On the island Onrust, convicts were used at the wharf and the military station. In 1912, some 600 convicts were employed on the island for constructing a quarantine station for hadj travellers.Footnote 36 Sometimes, the boundaries between public and private employment were vague. In 1844, for example, the Resident of the Preanger district (Java) wanted to employ 300 kettingjongens (convicts) at the two factories of an emerging tea plantation. Later, some fifty-five convicts were employed at Wonosobo (Java), sawing planks for some 3,000 chests that were needed for the transport of tea.Footnote 37 Over time, the department of civic public works (Burgerlijke Openbare Werken, BOW) gained increasing control over the work undertaken by convicts on infrastructural projects. In the early 1920s, for example, the BOW employed some one hundred convicts on the small island of Pulau Pandan, just off Padang (Sumatra), collecting granite under the supervision of a European overseer and a number of policemen.Footnote 38 In 1919, the Director of the BOW declared that he aimed to employ some 4,000 convicts per day on the construction of the road to Korintji (southwest Sumatra) in order to finish it in two years’ time.Footnote 39

As corvée labour declined, large-scale projects came to rely increasingly on convict labour. In the early nineteenth century, irrigation projects were undertaken mainly using contract labour (coolies), with local populations providing corvée labour. In the 1880s, it was suggested employing convict labour on irrigation works.Footnote 40 And, in 1891, the colonial press discussed the benefits of replacing the “3,000 free coolies” at the irrigation works of Demak (Central Java) by convict labourers.Footnote 41 From the early twentieth century, large-scale irrigation projects in southwest Djember (East Java) started to use convicts. Convicts were reported to be employed near Rambipuji and Bedadung in the 1910s, and near the Djatiroto sugar enterprise in the 1920s. In the 1930s, convicts were employed in Besuki (north coast of East Java).

These convicts were mainly serving medium-term sentences. The transportation time to the irrigation works limited the scope for employing convicts serving the shortest sentences, but the minimum requirements were low. For the Bedadung project, it was reported in 1912 that convicts “who had been sentenced to krakallen [in this context referring to general coerced labour on infrastructure] for a duration longer than eight days were sent there”.Footnote 42 On the Besuki irrigation projects in the 1930s, convicts were “selected especially whose duration of punishment expires within eighteen months at the latest”.Footnote 43 One of the main reasons for sending convicts with medium-term sentences was the unhealthy conditions at the irrigation projects, which formed a breeding ground for all kinds of disease. At the Bedadung project, convicts referred to a widespread disease called sakit kring, while colonial doctors at Besuki reported “pneumonia, dysentery, and influenza”.Footnote 44

Convicts were often brought from prisons in nearby cities. In 1912, it was reported from Bondowoso that convicts had been sent to the Bedadung irrigation works from a prison in “Tjoeradmalang” – which had a capacity of 720 to 840 convicts.Footnote 45 To balance project demands and the unhealthy environment, convicts employed on irrigation works seem to have been moved around continuously. In the 1930s, the convicts for the irrigation projects in East Java were reported to have been stationed in South Banjoewangi (1,500), in Pondok Lawu (500), and in Kasijam and Woeloehan (500). The convicts stationed in Woeloehan were explicitly said to be “unfit for the hard work demanded at the irrigation works”. They were employed at an agricultural enterprise, growing rice and vegetables to feed the prisoners.Footnote 46

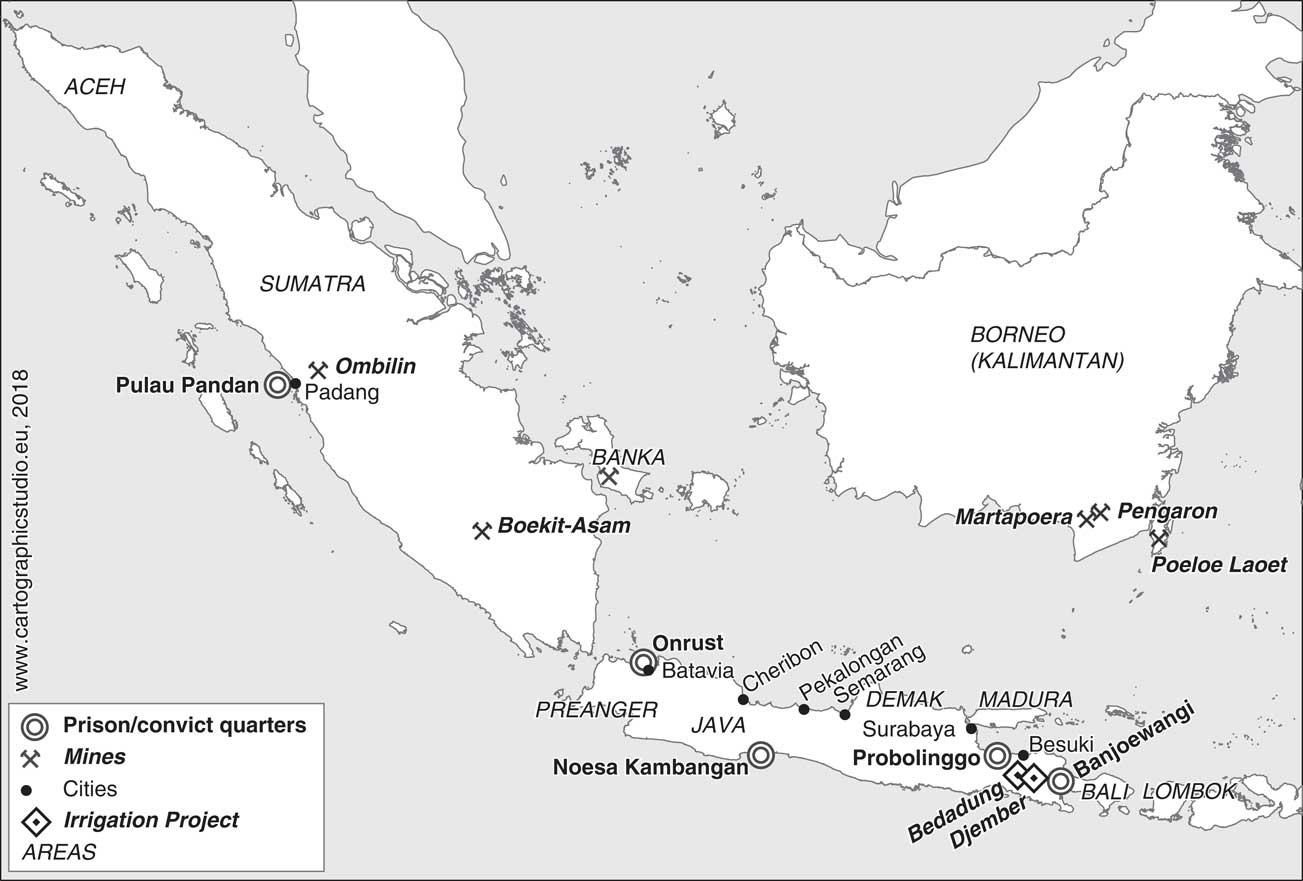

Figure 4 Location of penal institutions and sites of convict labour in the Dutch East Indies.

From the early nineteenth century, convicts serving medium- to long-term sentences were regularly employed on military expeditions as porters and as general labourers. Some 300 Javanese convicts were sent along with Colonel Bauer’s regiment to join the expedition to Bonjol in 1835.Footnote 47 During the Timor expedition of 1857, the 250 “press-ganged coolies” were soon replaced by convict labourers. After the conquest of the Lampong region (South Sumatra) in 1859, it was reported that “in those and following years a great number of regiments of forced labourers and chained convicts were transported from Anjer via the Sunda Straits to Teloengbetoeng for the construction of roads and the rebuilding of this city”.Footnote 48 The expeditions during the colonial wars in Aceh between 1873 and 1903 were accompanied by some 500 to 1,000 convicts yearly. Van Heutsz’s 1898 expedition included more than 3,800 convicts.Footnote 49 Convicts were employed in other colonial wars simultaneously. The Lombok expedition of 1894 included some 1,000 convicts, while 250 convicts were sent with the New Guinea expedition in 1902, and some 500 convicts were sent on the expedition to Korintji (west coast of Sumatra) in 1903.Footnote 50 It is estimated that, after 1903, some 700 convicts were employed for military purposes each year.Footnote 51

Figure 5 Transport of guns by four columns of forced labourers from Aceh, during the seventh Bali expedition. 1906. KITLV 43219. Creative Commons CC-BY License.

Convicts were also sent out on other types of expedition, especially exploratory geological missions under the command of mining and geology experts. In 1854, for example, forty-eight convicts were employed under the engineer Schreuder on the island of Batjan (Moluccas) in search of coal and gold.Footnote 52 The military and mining expeditions competed for the same convict workers as the mines and other operations using long-sentence convicts. In July 1861, a colonial journal of natural sciences reported that “in the course of this month twenty-one kettinggangers were sent to the coal mines of Koetei [Pelarang, East Kalimantan], and thirty-one kettinggangers departed with a military expedition to Kanangan [South Kalimantan] to provide coolie services”.Footnote 53 These instances indicate the close connections between the military, the colonial bureaucracy, and specialists such as geologists. Geological exploration missions and mines were protected by military regiments, while convicts were withdrawn from mines and other projects to supply the necessary support for military expeditions.

The mines were perhaps one of the most important places where convicts were employed (Tables 2 and 3). The Banka tin mines had been a destination for convicts from as early as the early nineteenth century. The mines were operated mainly by Chinese contract labourers, but convicts continued to be employed there until the early twentieth century.Footnote 54 In the 1840s, the colonial government experimented with coal mining near Martapoera (South Kalimantan). The experiment at the mining site “De Hoop” was short-lived.Footnote 55 From 1849 to 1884 the “Oranje Nassau” coal mines in Pengaron (near Banjermassin, South Kalimantan) were run by the colonial government using convict labour. Convicts were reported to have been brought from Java, Madura, and Bali.Footnote 56 Between 1860 and 1873 the government coal mine at Pelarang (East Kalimantan) was also operated using convicts as miners.Footnote 57

Table 3 Importance of convict labour in coal and rubber sector, Dutch East Indies, 1910–1923.

In 1892, the colonial government started to exploit coal mines in the Ombilin region. The railway between Ombilin and Padang needed to transport the coal was constructed by convict workers. The mines began operating with a workforce of some 300 convicts in January 1893. By the end of the year this number had grown to some 1,250. The workforce continued to grow, to over 2,400 convicts by April 1898. The next month, the workforce was reduced as large numbers were used for the military expedition to Aceh.Footnote 58 In subsequent years, the size of the workforce slowly rose again, with some 2,000 convicts being deployed around 1900. From the late 1890s onwards, increasing numbers of contract workers, too, were employed at the mines. By 1910, the workforce at the Ombilin mines consisted of 1,620 convicts and 4,761 contract workers.Footnote 59 In the 1920s, the “capacity” of Sawah Loento was 1,790 convicts.Footnote 60 Nevertheless, the convict population was more than double this figure by the early 1920s, peaking at 4,747 convicts in 1922.

The Ombilin mines provide an interesting insight in the financial organization of government undertakings that deployed convict labour. In the first few years of its operation (1893–1894) all costs related to the convict workforce were charged to the government’s mining company. Only the expenses incurred for the convicts’ clothing were paid from the Department of Justice’s budget.Footnote 61 This changed after large numbers of convicts were withdrawn from the Ombilin mines to join the military expedition to Lombok in the autumn of 1894. The directors of the mines complained that the “able-bodied forced workers” were taken to Lombok, while “the majority of the remaining [convicts] consisted of the less useful and ill”. The several hundred hired workers – mostly Chinese and some from Nias – cost the mines forty to fifty cents per day. This led to a new arrangement from 1895 onwards in which the Department of Justice agreed to pay all costs relating to convicts sent to the Ombilin mines, while the mining company was charged a fixed amount for every day the convicts worked for the company, regardless of whether it was inside or outside the mines.Footnote 62

Convicts were also deployed in the coal mines on Poeloe Laoet (southeast Kalimantan). The mine was started by a private company, but was taken over by the colonial government in 1913. In 1924, some 980 convicts were employed out of a total workforce of over 2,000. By 1929, the total workforce had grown to almost 3,300, while the number of convicts had decreased to somewhat over 700.Footnote 63 In 1919, the colonial government started to operate another coal mine in Boekit-Asam (Sumatra). For most of its existence the mine was operated using Chinese contract workers, but for a brief period in the early 1920s large numbers of convicts were brought in. The much criticized first director of the mine, Tromp, would later recall that problems with Chinese contract workers were the reason for this. He complained that it was difficult to get Chinese workers to work, and it did not help “to send the coolie to the magistrate for punishment”.

These lazy workers did not mind taking a holiday from the mines and being required to carry out easy work (cleaning the roads, etc.). At the request of the manager of the prisons department, a temporary measure permitted putting the politioneel gestraften (convicts sentenced under police law) to work in the mine. A group of convicts would be put to work under the supervision of armed police, but these workers performed just as little.Footnote 64

In the Ombilin mines, convicts worked around the clock in eight-hour shifts. European overseers were assisted by mandoers, selected from among the most hardworking and loyal convicts. In their quarters, convicts were monitored by a European prison warder and several mandoers.Footnote 65 In the mines, convicts were employed on work deep in the shafts; contract workers were employed on less risky tasks. The death tolls following explosions in mineshafts indicate that this was the case elsewhere too. An explosion in the Poeloe Laoet mine in 1924, for example, killed sixty-three workers, of whom fifty-seven were convicts and only five were contract workers.Footnote 66

Conditions in the mines were tough and the disciplinary regime was brutal. The records indicate that thousands of beatings using rattan sticks were carried out every year at the Ombilin mines alone. The period 1922–1924 was marked by a severe crisis in the disciplinary regime. Perhaps due to overpopulation, the number of registered rattan beatings inflicted on the mines’ convict population more than doubled in these years. This was followed by a sharp rise in the number of cases of solitary confinement and attempts to desert.Footnote 67 Desertion was a common phenomenon. As early as 1894, it was noted that 176 convicts had attempted to run away in the first eleven months – given an average convict population this meant a desertion rate of nineteen per cent. Most convicts were recaptured (146), bringing the real annual rate of desertion to some three per cent.Footnote 68 At times, the rate of successful desertion increased to six per cent, not only at Ombilin but also at the Djember irrigation works. Noesa Kambangan seems to have had lower desertion rates, perhaps because it is an island.Footnote 69 Similar arguments were used in favour of deploying convicts at the mines on the island of Poeloe Laoet instead of at the Ombilin mines.Footnote 70 In most places, a range of disciplinary measures were employed, varying from severe punishments (rattan-stick beatings) to monitoring the quarters and workplaces of the convicts, and from policing nearby public locations (the passar – market) to rewarding local residents for returning runaway convicts.Footnote 71

From the late nineteenth century, the landscape of penal institutions was broadened to include institutions that seem to have aimed at combining the profitability of convict production with more rehabilitative elements (Table 2).Footnote 72 In 1881, a budget of 100,000 guilders was approved for the construction of new quarters for convict workers in Semarang and a central prison for men in Surabaya.Footnote 73 The Semarang prison, Mlaten, was still being referred to as a dwangarbeiderskwartier (forced workers’ quarters) in the 1910s,Footnote 74 but it was used as a kleermakerij, a workshop for the production of clothing.Footnote 75 Other convict quarters were renewed or replaced by new prison buildings. The main aim seems to have been to make prisons into more effective production sites. The Yogyakarta prison housed over 1,000 convicts in the mid-1920s and functioned as a leather workshop. The central prison in Cheribon was a textile factory. Production capacity there was increased from 100 looms in 1921 to 212 looms in 1926. Half of the looms were driven by a steam engine, the other half by an electric motor. The prison housed 900 convicts, with a daily convict workforce of 600, producing 1.4 million metres, mostly dyed, per annum. Convicts were incentivized to increase production. Unwilling convicts were isolated and forced to work on “the old Dutch handloom”.Footnote 76 In the Tjipinang prison in Batavia in 1930, the 2,400 convicts produced clothing, sheets, uniforms, furniture, and other goods needed by the various departments of the colonial government or army. The 550 communist prisoners were separated in an enclosed department, to work on administrative tasks or make bamboo heads.Footnote 77 The Pekalongan prison functioned first as a printing press and bookbinding workshop (1925) and later also produced carpets and kitchen goods (1929). In the 1930s, it was referred to as kokosbedrijf – a workshop processing coconuts.Footnote 78

Alongside these prison factories, the colonial government created an agricultural colony on the island of Noesa Kambangan.Footnote 79 Soon after its creation in 1903, the colony was used as a rubber plantation, deploying convict labourers. The role of this project within the wider carceral system should be scrutinized further, especially since the prison-based production of rubber could hardly compete with the market (mainly “native”) production of rubber (Table 3). In 1922, Noesa Kambangan housed more than 3,200 convicts, mainly employed on collecting rubber and other work related to the plantation. Nearby prisons housed smaller groups of convicts – the most important being the prisons in Karang-Anjar (425) and Gliger (350).Footnote 80 The convicts came from different parts of the Dutch East Indies (especially Java and Aceh). In 1926, roughly 700 convicted communists were sent to Noesa Kambangan and remained there until they were transferred to prisons in Pamekasan (East Java) and Ambarawa (Central Java) in 1932.Footnote 81 Meanwhile, the population of the agricultural colony increased to over 4,000 convicts by the end of the 1920s.Footnote 82 The conditions on Noesa Kambangan, especially the unhealthy living conditions there and the scope for desertion, were a recurrent theme in the colonial press.Footnote 83

The impact of convict labour varied by sector. As the extraction of coal was vital for most of the operations forming the backbone of the colonial project – from transport to warfare – the colonial government held a tight grip on the coal-mining sector and operated its mines to a large extent using the cheap labour extracted from long-term convicts. The proportion of coal mines in the Dutch East Indies using convict labour declined only slowly, as more mines opened and production doubled in the course of the first half of the twentieth century. In the field of rubber production, the reverse was the case. Although rubber was a vital commodity, the proportion of total government production that involved the use of convicts was fairly small, and generally took the form of private production throughout the Dutch East Indies. However, the Noesa Kambangan was a large and, initially, very profitable undertaking. It was also argued that teaching convicts the skills required to produce rubber during their time in prison would have beneficial effects. Similar arguments were made to justify the large-scale and growing production of commodities in colonial prisons from the 1910s and 1920s onwards.

CONCLUSION: CARCERAL REGIME AND COLONIAL EXPLOITATION

Thinking in terms of “prisons” can be misleading if we want to understand the Dutch colonial carceral system. At the height of the colonial penal industry, convicts were deployed in a broad range of colonial activities, including military expansion (warfare), creating and maintaining colonial infrastructure (roads, railways, waterways), extracting crucial resources (tin, coal), and producing for world markets (rubber) and to meet colonial-bureaucratic needs (varying from uniforms to furniture). Convict labour was strategic in supporting the colonial project. The function of the penal system was twofold. Firstly, convict labour as a form of punishment had a disciplinary function. Over the course of the nineteenth century, the use of administrative measures to sentence colonial subjects to convict labour were strongly expanded, strengthening the carceral connection between the different colonial coercive labour regimes. These convicts were sentenced under the politierol, or police law, to short-term convict labour (tenarbeidstelling). This route was adopted increasingly in the final decades of the nineteenth century, with the government administration of these sentences disappearing from the records after 1900, by which time the number of convictions had peaked at 275,000 per annum. The number of convicts sentenced to medium- or long-term convict labour by the criminal courts (landraad and Raad van Justitie) was much smaller. The average size of this population “in prison” nevertheless grew over time. Overall, the Dutch East Indies witnessed a carceral boom, with both the colonial sentencing rate and the prison population increasing greatly between 1870 and 1920 (Table 1).

Secondly, the carceral system had a productive function in the colonial production regime, supporting the various colonial aims with regard to expansion, infrastructure, extraction, and actual production. All convicts in the Dutch East Indies were employed as forced labourers, and most them worked at extramural convict sites. Convicts were initially concentrated in activities related more to the infrastructural and expansionist aims of the colonial government. Responding to the abolition of the slave trade, however, the authorities started to send convicts to Bandanese and Javanese plantations. Increasingly, convicts were also deployed in the Banka tin mines, and later in the coal mines of Sumatra and Kalimantan. It was only towards the end of the nineteenth century that we see something of a shift towards the deployment of convicts in more enclosed production sites, both “outdoor” (the Noesa Kambangan rubber colony) and “indoor” (the expanding prison factories). The colonial government continued to employ convicts, however, in large-scale extramural and expansionist projects. The first half of the twentieth century especially witnessed ever larger numbers of convicts being sent to work on irrigation projects in East (and Central) Java, paving the way for the growing colonial plantation economy.

What should we make of this understudied aspect of Dutch colonial history? The convict system was not merely about mobilizing labour through the coercive means of convict labour relations. The nature of the system was more strategic. The productive and disciplinary functions of the penal system were key elements of a colonial regime effectively weaving together control, coercion, and exploitation. This was not just an early exercise in something that we nowadays try to understand as the “carceral state”; it must be understood, too, as a matured form of a phenomenon that actually seems to have been one of the roots of present-day carceral regimes, the “carceral colony”.