Published online by Cambridge University Press: 06 October 2010

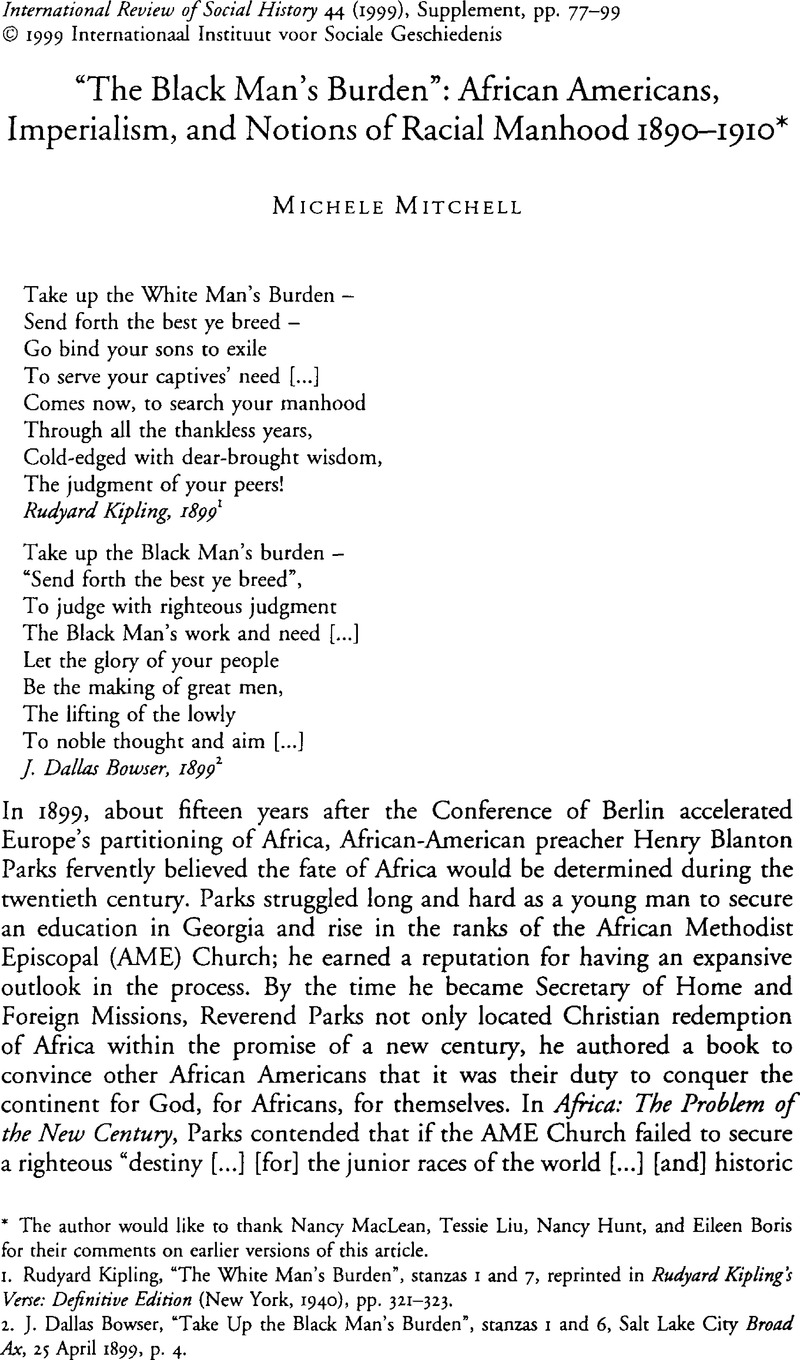

1 Kipling, Rudyard, “The White Man's Burden”, stanzas i and 7, reprinted in Rudyard Kipling's Verse: Definitive Edition (New York, 1940), pp. 321–323Google Scholar.

2 Bowser, J. Dallas, “Take Up the Black Man's Burden”, stanzas 1 and 6, Salt Lake City Broad Ax, 25 04 1899, p. 4Google Scholar.

3 Parks, H[enry] B[knton], Africa: The Problem of the New Century; The Part the African Methodist Episcopal Church is to Have in its Solution (New York, 1899), pp. 5, 8–9, 20.Google Scholar For biographical information, see Talbert, Horace, The Sons of Allen (Xenia, OH, 1906), pp. 212–214Google Scholar.

4 Overviews of Afro-American viewpoints on European campaigns in Africa include Jacobs, Sylvia, The African Nexus: Black American Perspectives on the European Partitioning ofAfrica, 1880–1920 (Westport, CT, 1981) andGoogle ScholarSkinner, Elliott P., African-Americans and US Policy Toward Africa, 1850–1924: In Defense of Black Nationality (Washington DC, 1992).Google Scholar For analysis of the AME Church and its complex relationship to Africa, see Campbell, James T., Songs of Zion: The African Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States and South Africa (New York, 1995)Google Scholar.

5 See Williams, Walter L., “Black Journalism's Opinions About Africa During the Late Nineteenth Century”, Phylon: The Atlanta University Review of Race and Culture, 34 (1973), pp. 224–235;CrossRefGoogle Scholaridem, Black Americans and the Evangelization of Africa, 1877–1900 (Madison, WI, 1982); Gaines, Kevin, ”Black Americans’ Racial Uplift Ideology as ‘Civilizing Mission’: Pauline E. Hopkins on Race and Imperialism”, in Kaplan, Amy and Pease, Donald E. (eds), Cultures of United States Imperialism (Durham, NC, 1993), pp. 433–455Google Scholar.

6 Fortune, T. Thomas, “The Nationalization of Africa”, in Bowen, J. W. E. (ed.), Africa and the American Negro: Addresses and Proceedings on the Congress of Africa […] (Atlanta, GA, 1896), pp. 199–204, esp. pp. 201, 203–204. ConsultGoogle ScholarAllman, Jean M. and Roediger, David R., “The Early Editorial Career of Timothy Thomas Fortune: Class, Nationalism and Consciousness of Africa”, Afro-Americans in New York Life and History, 6 (1982), pp. 39–52Google Scholar for analysis of Fortune's editorial writing.

7 Wells, Ida B., “Afro-Americans and Africa”, AME Church Review, 9 (1892), pp. 40–44, esp. p. 41Google Scholar; Johnson, S.H., “Negro Emigration: A Correspondent Portrays the Situation and the Benefito t Be Derived by Emigration”, Indianapolis Freeman, 26 03 1892, p. 3Google Scholar; , Parks, Africa: The Problem of the New Century, pp. 20–22Google Scholar.

8 , Parks, Africa: The Problem of the New Century, pp. 29–30, 41Google Scholar.

9 Ibid., pp. 7, 8–9, 20, 48.

10 Ibid., p. 7.

11 Hofstadter, Richard, Social Darwinism in American Thought: 1860–1915 (New York, 1959)Google Scholar; Meier, August, Negro Thought in America, 1880–1915 (Ann Arbor, MI, 1966)Google Scholar; Chamberlin, J. Edward and Gilman, Sander L. (eds), Degeneration: The Dark Side of Progress (New York, 1985)Google Scholar.

12 For commentary on gendered subtexts of imperialism, race, Social Darwinism and civilization in fin de siècle thought, consult Bederman, Gail, Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880–1917 (Chicago, IL, 1995)CrossRefGoogle Scholar and Breman, Jan (ed.), Imperial Monkey Business: Racial Supremacy in Social Darwinist Theory and Colonial Practice (Amsterdam, 1990)Google Scholar. , Parks, Africa: The Problem of the New Century, pp. 8–9, 22, 40–51, 43. For observations by Turner, seeGoogle ScholarRedkey, Edwin S. (ed.), Respect Black: The Writings and Speeches of Henry McNeal Turner (New York, 1971), pp. 124, 159.Google Scholar Analysis of civilizationist suppositions within AfroAmerican appropriations of Social Darwinism may be found in , Gaines, “Black Americans’ Racial Uplift Ideology as ‘Civilizing Mission’”, pp. 433–455, esp. p. 438, andGoogle Scholar, Williams, “Black Journalism's Opinions About Africa During the Late Nineteenth Century”, p. 230Google Scholar.

14 Although this essay deals with the industrial age, applying standard class labels — “working class”, “bourgeois”, “owning class” — to African Americans who lived between 1890 and 1910 would obscure the specific circumstances of a people barely a generation removed from slavery. Since over seventy per cent of African Americans still resided in the rural south by 1900 and approximately ninety per cent were workers, I use slightly different terminology. “Working poor” refers to people who struggled to survive — sharecroppers, domestics, underemployed seasonal laborers. “Aspiring class” refers to workers — from seamstresses to skilled tradesmen to teachers to small proprietors — able to save a little money. These women and men were concerned with appearing “respectable”; many had normal school education or were self-educated and some worked multiple jobs in order to attain class mobility. “Elite” refers to college-educated professionals, many of whom were prominent in national organizations, owned well-appointed homes, and had successful businesses.

15 For analysis of black women's political activism during these years, see Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks, Righteous Discontent: The Women's Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880–1920 (Cambridge, MA, 1993),Google ScholarGilmore, Glenda Elizabeth, Gender & Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896–1920 (Chapel Hill, NC, 1996),Google ScholarShaw, Stephanie J., What a Woman Ought to Be and To Do (Chicago, IL, 1996), andCrossRefGoogle ScholarWhite, Deborah Gray, Too Heavy a Load: Black Women in Defense of Themselves, 1894–1994 (New York, 1999)Google Scholar.

16 See, for example, Gatewood, Willard B. Jr, “Negro Troops in Florida, 1898”, Florida Historical Quarterly, 49 (1970), pp. 1–15;Google Scholaridem, “Black Americans and the Quest for Empire, 1898–1903”, Journal of Southern History, 38 (1972), pp. 545–66; idem, Black Americans and the White Man's Burden, 1898–190} (Urbana, IL, 1975); Welch, Richard E. Jr, Response to Imperialism: The United States and the Philippine–American War, 1899–1902 (Chapel Hill, NC, 1979), pp. 101–116;Google ScholarGaines, Kevin and Eschen, Penny von, “Ambivalent Warriors: African Americans, US Expansion, and the Legacies of 1898”, Culture Front, 8 (1998), pp. 63–64, 73–75Google Scholar.

17 Fredrickson, George M., The Black Image in the White Mind: The Debate on Afro-American Character and Destiny, 1817–1914 (New York, 1971), pp. 97–129,Google Scholarpassim; Horton, James Oliver, “Freedom's Yoke: Gender Conventions Among Antebellum Free Blacks”, Feminist Studies, 12 (1986), pp. 51–76, esp. p. 53CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

18 [Quotation from Wells, Ida B.], Voice of Missions, 06 1894, p. 2Google Scholar.

19 Elsa Barkley Brown offers powerful commentary on past and present tendencies to view lynching as a “masculine experience”. See Brown, , “Imaging Lynching: African American Women, Communities of Struggle, and Collective Memory” in Geneva Smitherman (ed.), African-American Women Speak Out on Anita Hill–Clarence Thomas (Detroit, MI, 1995), pp. 100–124Google Scholar, esp. 101–102.

20 Turner, Henry McNeal, “Essay: The American Negro and the Fatherland”, in Bowen, Africa and the American, pp. 195–198, esp. p. 197. (Italics in original.)Google Scholar

21 See Love, Reverend Emanuel K., “Oration Delivered on Emancipation Day” (2 01, 1888),Google ScholarCollection, Daniel A.P. Murray Pamphlet, Library of Congress, Washington DC; Gaines, Wesley J., The Negro and the White Man (Philadelphia, PA, 1897)Google Scholar; Fulton], Jack Thorne [David Bryant, A Plea for Social justice for the Negro Woman (New York, 1912)Google Scholar.

22 Vance, Norman, The Sinews of the Spirit: The Ideal of Christian Manliness in Victorian Literature and Religious Thought (Cambridge, 1985), p. 1Google Scholar.

23 See David Leverenz's discussion of Douglass, Frederick in Manhood and the American Renaissance (Ithaca, NY, 1989), pp. 108–134Google Scholar.

24 Norman, Lucy V., “Can a Colored Man Be a Man in die South?”, Christian Recorder, 3 07 1890, p. 2Google Scholar; , Turner, “Essay: The American Negro and die Fatherland”, pp. 195–198, esp. p. 195; (italics in original.)Google Scholar

25 Redkey, Edwin S., Black Exodus: Black Nationalist and Back-to-Africa Movements, 1890–1910 (New Haven, CT, 1969), pp. 1–23,Google Scholarpassim. For representative primary evidence, see Coppinger, I.W. Penn to William, 10 04 1891, American Colonization Society Papers, Library of Congress, Washington DC [hereafter, ACSP], container 280, vol. 283Google Scholar.

26 See, for example, African Repository, 43 (1887), pp. 49–51 andGoogle ScholarAfrican Repository, 46 (1890), pp. 49–51;Google ScholarCoppinger, Mary E. Jackson to, 20 05 1891, ACSP, container 280, vol. 283.Google Scholar For evidence of independent black emigration societies, see Coppinger, Mary E. Jackson to, 16 06 1891, ACSP, container 280, vol. 283Google Scholar.

27 Wilson, Lewis Lee to J. Ormond, 23 10 1894, ACSP, container 286, vol. 291Google Scholar; Wilson, John Lewis to, 31 01 1893, ACSP, container 288, vol. 294Google Scholar; Wilson, R. A. Wright to, 26 02 1894, ACSP, container 286, vol. 291Google Scholar; Coppinger, F.M. Gilmore to, 15 04 1891, ACSP, container 280, vol. 283Google Scholar; Coppinger, James Dubose to, 12 02 1891, ACSP, container 279, vol. 282Google Scholar.

28 Taylor, C.H.J., Whites and Blacks, or The Question Settled (Atlanta, GA, 1889), pp. 33–34, 37, 39. 29Google Scholar.

29 Smith, Amanda, An Autobiography: The Story of the Lord's Dealings with Mrs. Amanda Smith, the Colored Evangelist (Chicago, IL, 1893)Google Scholar.

30 , Smith, Autobiography, pp. 331–465, esp. pp. 414–417; (italics in original)Google Scholar.

31 Ibid., pp. 451–463; “Amanda Smith's Letter”, Voice of Missions, 07 1895, p. 2Google Scholar.

32 Coppin, Levi J., “Editorial: What Shall We Do?”, AME Church Review, 10 (1894), pp. 549–557, esp. pp. 551–552Google Scholar.

33 See, for example, Coppinger, J.H. Harris to, 5 08 1891, ACSP, container 281, vol. 284Google Scholar.

34 “Made a Fortune in Liberia”, Liberia Bulletin, 9 (1896), pp. 84–86;Google ScholarWilson, A.L. Ridgel to, ACSP, I 06 1894, container 286, vol. 291, reel 143; (emphasis in original)Google Scholar.

35 Arnett, Benjamin W., “Africa and the Descendants of Africa: A Response in Behalf of Africa”, AME Church Review, II (1894), pp. 231–238. esp. p. 233Google Scholar.

36 Smyth, J.H., “The African in Africa and the African in America”, in , Bowen, Africa and the American Negro, pp. 69–83, esp. pp. 74, 77Google Scholar.

37 Interestingly, V.G. Kiernan points out that “a large part of the army defeated at Adowa in 1896 was composed of men from […] Afric[a]”. See , Kiernan, “Colonial Africa and its Armies”, in Kaye, Harvey J. (ed.), Imperialism and Its Contradictions (New York, 1995), pp. 77–96, esp. p. 83Google Scholar.

38 Sarah Dudley [Mrs C.C.] , Pettey, A.M.E.Z. Church Quarterly, 7 (1897), p. 30Google Scholar.

39 Cullen, Jim, “Is a Man Now’: Gender and African-American Men”, in Clinton, Catherine and Silber, Nina (eds), Divided Houses: Gender and the Civil War (New York, 1992), pp. 76–91, esp. p. 77Google Scholar; Gaines, and Eschen, von, “Ambivalent Warriors”, p. 64Google Scholar.

40 , ParsonsWeekly Blade, 9 07 1898Google Scholar; , WashingtonColored American, 30 04 1898Google Scholar; , CoffeyvilleAmerican, 7 05 1898, all quoted inGoogle ScholarMarks, George P. (ed.), The Black Press Views American Imperialism, 1898–1900 (New York, 1971), pp. 70, 53Google Scholar.

41 , WashingtonBee, 21 05 1898, p. 5.Google Scholar This notice about Burroughs’ speech, “Should the Negro Take Part in the Spanish-American Trouble?”, is a summary and thus the text quoted above might not be her actual wording.

42 Gatewood, Willard B. Jr, (ed.), “Smoked Yankees” and the Struggle for Empire: Letters from Negro Soldiers, 1898–1902 (Urbana, IL, 1971), pp. 55–57Google Scholar.

43 Washington, Booker T. et al., A New Negro for a New Century (Chicago, IL, 1900), pp. 40–41;Google ScholarKaplan, Amy, “Black and Blue on San Juan Hill”, in , Kaplan and , Pease, Cultures of United States Imperialism, pp. 219–236, esp. p. 226Google Scholar.

44 Crogman, W.H., “The Negro Soldier in the Cuban Insurrection and Spanish-American War”, in Nichols, J.L. and Crogman, William H. (eds), Progress of a Race or the Remarkable Advancement of the American Negro […], revised and enlarged (Naperville, IL, 1925), pp. 131–145, esp. pp. 137–138.Google Scholar For additional commentary that black troops “saved” the Rough Riders, see Cashin, Herschel V. et al., Under Fire with the Tenth US Cavalry (New York, 1899)Google Scholar.

45 Steward, Theophilus G., The Colored Regulars in the United States Army (Philadelphia, PA, 1904), illustration between pp. 230–231;Google ScholarTillman, Katherine Davis Chapman, “A Tribute to Negro Regiments”, and “The Black Boys in Blue”, in Tate, Claudia (ed.), The Works of Katherine Davis Chapman Tillman (New York, 1991), pp. 146, 188–189;Google ScholarBrazley, Stella A.E., “The Colored Boys in Blue”, in Coston, W. Hilary, The Spanish-American War Volunteer (Middletown, PA, 1899), p. 81.Google Scholar See also Mason, Lena, “A Negro In It”, in Culp, D.W. (ed.), Twentieth Century Negro Literature or, A Cyclopedia of Thought on the Vital Topics Relating to the American Negro (Naperville, IL, 1902), p. 447.Google Scholar For a decidedly anti-war poem, see Harper, Frances E.W., “Do Not Cheer, Men Are Dying”, , RichmondPlanet, 3 12 1898Google Scholar.

46 , Crogman, “The Negro Soldier in the Cuban Insurrection and Spanish-American War”, Progress of a Race, pp. 135–144;Google Scholar“B, W. A..”, “The Rough Rider ‘Remarks’”, World, 22 08 1898,Google Scholar in Under Fire with the Tenth US Cavalry, pp. 277–279; Lynk, Miles V., The Black Troopers, or The Daring Heroism of The Negro Soldiers in the Spanish-American War (Jackson, TN, 1899), pp. 18, 69–70. See alsoGoogle Scholar, Gatewood, “Smoked Yankees”, p. IIGoogle Scholar.

47 , Washington, Colored American, ca. 1899, quoted inGoogle Scholar, Gatewood, “Smoked Yankees”, p. 237Google Scholar; , KansasCity American Citizen, 28 04 1899 andGoogle Scholar Helena Reporter, I February 1900, both quoted in , Marks, The Black Press Views American Imperialism, pp. 124–125, 167Google Scholar.

48 , Gatewood, “Smoked Yankees”, pp. 247–249Google Scholar.

49 Ayers, Edward L., The Promise of the New South: Life after Reconstruction (New York, 1992), P. 333Google Scholar

50 , Gatewood, “Smoked Yankees”, pp. 88–89, 85Google Scholar.

51 , Kaplan, “Black and Blue on San Juan Hill”, p. 235Google Scholar.

52 Fortune, T. Thomas, “The Filipino: A Social Study in Three Parts”, Voice of the Negro, I (1904), pp. 93–99, esp. pp. 96–97Google Scholar.

53 , Fortune, “The Filipino: Some Incidents of a Trip Through the Island of Luzon”, Voice of the Negro, I (1904), pp. 240–246, esp. p. 246Google Scholar.

54 Hopkins, Pauline, Of One Blood: or, the Hidden Self, in Carby, Hazel V. (ed.), The Magazine Novels of Pauline Hopkins (New York, 1988), pp. 441–621;Google ScholarFowler, Charles H., Historical Romance of the American Negro (Baltimore, MD, 1902)Google Scholar; Grant, J[ohn] W[esley], Out of the Darkness; or, Diabolism and Destiny (Nashville, TN, 1909)Google Scholar; Griggs, Sutton E., Imperium in Imperio (Cincinnati, OH, 1899)Google Scholar; , Griggs, Unfettered: A Novel; with Dorian's Plan (Nashville, TN, 1902)Google Scholar; , Griggs, The Hindered Hand (Nashville, TN, 1905)Google Scholar.

55 , Griggs, Unfettered, pp. 256–257, 275Google Scholar.

56 , Griggs, Imperium, p. 62Google Scholar.

57 Ibid., pp. 132–135, 173–174.

58 Ibid., pp. 173–175. The work referred to in the suicide letter is Evrie, J.H. Van MD, White Supremacy and Black Subordination, or, Negroes a Subordinate Race, And (So-Called) Slavery its Normal Condition (New York, 1868), esp. pp. 149–167Google Scholar.

59 Kaplan, Amy, “Romancing the Empire: The Embodiment of American Masculinity in the Popular Historical Novel of the 1890s”, American Literary History, 2 (1990), pp. 659–690, esp. p. 672.CrossRefGoogle Scholar For commentary on historical romances written by African Americans, see Payne, James Robert, “Afro-American Literature of the Spanish-American War”, Melus, 10 (1983), pp. 19–32, esp. pp. 27–29CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

60 McGirt, James E., “In Love as in War”, in , McGirt, Triumphs of Ephraim (Philadelphia, PA, 1907), pp. 63–76, esp. p. 71.Google Scholar Background on the Philippine–American War may be found in Welch, Response to Imperialism.

61 , McGirt, “In Love as in War”, p. 75Google Scholar.

62 Miller, Kelly, “Immortal Doctrines of Liberty Ably Set Out by a Colored Man; The Effect of Imperialism Upon the Negro Race”, Springfield Republican, 7 09 1900, reprinted inGoogle ScholarFoner, Philip S. and Winchester, Richard C. (eds), The Anti-Imperialist Reader: A Documentary History of Anti-Imperialism in the United States. Volume 1: From the Mexican War to the Election of 1900 (New York, 1984), pp. 176–180, esp. p. 180.Google Scholar See also , Gatewood, “Black Americans and the Quest for Empire, 1898–1903”, p. 559Google Scholar.

63 Scarborough, W.S., “The Negro and Our New Possessions”, Forum, 31 (1901), pp. 341–349, esp. p. 347Google Scholar.

64 Walker, Walter F., “News about Liberia and Africa Generally”, Alexander's Magazine, 5 (01 1908), p. 67Google Scholar; , Walker, Alexander's Magazine, 6 (08 1908), pp. 162–166Google Scholar.

65 , Carby, “Introduction”, The Magazine Novels of Pauline Hopkins, p. xlvGoogle Scholar; , Gaines, “Black Americans’ Racial Uplift Ideology as ‘Civilizing Mission’”, p. 436. Insight on Du Bois’ anti-imperialism is offered inGoogle ScholarChristol, Helene, “Du Bois and Expansionism: A Black Man's View of Empire”, in Ricard, Serge and Christol, Helene (eds), Anglo-Saxonism in US Foreign Policy: The Diplomacy of Imperialism, 1899–1919 (Aix-en-Provence, 1991), pp. 49–63Google Scholar.

66 Curiously, the full quotation from the title page reads “[t]wo races hand in hand for mutual good”; Parks, Africa: The Problem of the New Century, title page.

67 , Gaines, “Black Americans’ Racial Uplift Ideology as ‘Civilizing Mission’”, pp. 437 and 440Google Scholar.

68 Crooke, I. De H., “Africa for Africans”, Colored American, 15 (1909), pp. 101–102;Google Scholar“The Grab for Liberia and Her Needs”, Colored American, 17 (1909), pp. 118–122;Google Scholar New York Age, 13 March 1913 and 13 November 1913, Tuskegee Institute News Clipping File, series I, main file, reel 2, frames 13 and 333.

69 , Skinner, African-Americans and US Policy Toward Africa, pp. 13–16Google Scholar.

70 See, for example, Riley, B.F., The White Man's Burden (Birmingham, AL, 1910),Google Scholar title page. Anne McClintock points out that the concept of a “white man's burden” could be crassly commercial: Pears’ Soap used the phrase as advertising copy. See , McClintock, Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality in the Colonial Conquest (New York, 1995), pp. 32–33Google Scholar.

71 Johnson, H.T., “The Black Man's Burden”, Salt Lake City Broad Ax, 15 04 1899, p. 4Google Scholar; Bruce, John E., “The White Man's Burden”, reprinted in Gilbert, Peter (ed.), The Selected Writings of John Edward Bruce: Militant Black Journalist (New York, 1971), pp. 97–98, esp. p. 97Google Scholar; , Miller, “Immortal Doctrines of Liberty Ably Set Out by a Colored Man”, pp. 176–180Google Scholar.

72 Davis, Daniel Webster, “The Black Woman's Burden”, Voice of the Negro, I (1904), p. 308Google Scholar; Bois, W.E.B. Du, “The Burden of Black Women”, reprinted in Lewis, David Levering (ed.), W.E.B. Du Bois: A Reader (New York, 1995), pp. 291–293;Google ScholarBois, W.E.B. Du (ed.), The Health and Physique of the Negro American (Atlanta, GA, 1906), p. 69Google Scholar.

73 Harper, Frances Ellen Watkins, “The Burdens of All” (ca. 1900), in Foster, Frances Smith (ed.), A Brighter Coming Day: A Frances Ellen Watkins Harper Reader (New York, 1990), p. 390Google Scholar.

74 , Bederman, Manliness and Civilization, p. 171Google Scholar.

75 For further commentary on Afro-American reworkings of Kipling, see , Gatewood, Black Americans and the White Man's Burden, pp. 183–186Google Scholar.

76 , Bederman, Manliness and Civilization, p. 5Google Scholar.

77 Morgan, Dennis H.J., “Theatre of War: Combat, the Military, and Masculinities”, in Brod, Harry and Kaufman, Michael (eds), Theorizing Masculinities (Thousand Oaks, CA, c. 1994), p. 165. Relevant texts include:Google ScholarCarnes, Mark C. and Griffen, Clyde (eds), Meanings for Manhood: Constructions of Masculinities in Victorian America (Chicago, IL, 1990)Google Scholar; Hearn, Jeff and Morgan, David (eds), Men, Masculinities, and Social Theory (London, 1990)Google Scholar; Kimmel, Michael, Manhood in America: A Cultural History (New York, 1996)Google Scholar; Stecopoulos, Harry and Uebel, Michael(eds), Race and the Subject of Masculinities (Durham, NC, 1997)Google Scholar; Clark, Darlene and Jenkins, Earnestine (eds), A Question of Manhood: A Reader in US Black Men's History and Masculinity (Bloomington, IN, 1999)Google Scholar.

78 Griffen, Clyde, “Reconstructing Masculinity from the Evangelical Revival to the Waning of Progressivism: A Speculative Synthesis”, in , Carnes and , Griffen, Meanings for Manhood, pp. 183–204, esp. p. 199Google Scholar; , Bederman, Manliness and Civilization, pp. 170–215;Google ScholarHoganson, Kristin, Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine American Wars (New Haven, CT, 1998), pp. 11–12Google Scholar.

79 , Hoganson, Fighting fir American Manhood, p. 12Google Scholar.