Wisdom is derived (in modern language terms) from the Old English words wis (“of a certainty, for certain”; “Wisdom,” 2015) and dóm (“statute, judgment, jurisdiction”; “Wisdom,” 2015); wisdom is, at its broadest, defined as the “Capacity of judging rightly in matters relating to life and conduct; soundness of judgement in the choice of means and ends; sometimes less strictly, sound sense, esp. in practical affairs” (“Wisdom,” 2015). As a concept, wisdom has been acknowledged within our history since the time of the Sumerians (and estimated to have originated in around 2,500 BCE). However, in modern times, the relevance of the traditional wise person is less clear. Nonetheless, wisdom research has been on the rise since it emerged as a focus of researchers in the 1970’s, and a part of that research focus has been to explore the significance of wisdom and its relevance in the current day (particularly with regards to how it is measured across cultures).

In the earliest writings concerned with wisdom, the focus was often on life lessons, ethical and moral codes, proverbs, and at its most basic level, the handing down of knowledge to others. The often cited example of King Solomon's wisdom (1 Kings 3:16-28 Good News Bible), for example, is the story of two women who each have a baby. One baby dies in the night and the two women argue over who will have the baby who lives. King Solomon suggests that the child be cut in half such that each woman can have one half each. The real mother's reaction to this suggestion is that the other woman should have the child, preferring that the child live with another than be killed. Solomon's decision is considered wise because it demonstrates an understanding of how a real mother would react to such a scenario. Confucius spoke of wisdom as a virtue and of wisdom being the result of actively reflecting on what has been learned, rather than passively learning and memorizing facts (Kim, Reference Kim2014). As such, the Analects of Confucius represent a collection of Confucius’ thoughts and teachings. In Book VI, for example, wisdom is described as “. . . devotion to perfecting your duties toward the people, and reverence for gods and spirits while keeping your distance from them . . .” (Hinton, Reference Hinton2013, p. 268). As these examples illustrate, history supports the notion that the prototypical wise man was someone who had knowledge and advice to offer others, particularly with regards to everyday living, but also with regards to things that were complex or perplexing.

The relevance of the prototypical wise person in the present, however, is less clear. With the internet, and a readily available and often compulsory educational system, the societal need for wise people may be reduced. Related to this is the need to consider that wisdom has generally been typified as something sought from external sources (i.e. from the prototypical wise man and similar protagonists within a given society, to more modern day iterations including Google, Wikipedia, and the Mayoclinic.org, for example). Alternately, research has considered the source of wisdom as being internal in nature, drawing on life experiences, past and current coping methods, and so forth, to assist in managing current issues, and to create and build resilience in the face of challenging decisions. Within this framework, wisdom may be something that can be developed within the individual (rather than from external sources) and therefore something amenable to change.

Over the past five decades, research has gradually increased in the area of wisdom, to investigate further a construct that has proven perplexing and challenging in nature. Defining the concept is an important first step, and yet the concept of wisdom remains elusive.

Defining wisdom: first step in psychological research on wisdom

Historically, wisdom is firmly embedded within philosophy (Robinson, Reference Robinson and Sternberg1990), with Before the Common Era (BCE) conceptualizations encompassing three elements: (1) sophia (the conceptual element of wisdom); (2) phronesis (practical wisdom); and (3) episteme (the science of wisdom).

From these earliest writings and into the 13th century within Western civilizations, wisdom was primarily characterized as providing advice for daily living; being knowledgeable; being supportive of the common good; living a good life and doing no wrong; morality; and being modest (Birren and Svensson, Reference Birren, Svensson, Sternberg and Jordan2005). Early Eastern civilizations characterized wisdom as knowledge gained from life experience and observation; developing an understanding of the nature of the world (both in life and in death); being compassionate; using intuition; morality; and living a good life (Birren and Svensson, Reference Birren, Svensson, Sternberg and Jordan2005). In the 16th century, reflection and reasoning, the unwillingness to accept things merely as they are, was added to the definition of wisdom (Birren and Svensson, Reference Birren, Svensson, Sternberg and Jordan2005). And within the most recent explorations of the concept, wisdom is primarily seen as being on the spectrum of decision making and judgment processes, while still incorporating other elements such as knowledge and the ability to reflect.

More specifically, modern definitions of wisdom incorporate many elements proposed in earlier times and have been separated into two broad categories: explicit definitions of wisdom and implicit definitions of wisdom. Explicit definitions of wisdom are understood as derived from expert opinion and knowledge. They are often based on theoretical models, in particular, the developmental models (e.g. Erikson's stages of psychosocial development, Piaget's cognitive stages of development). Implicit definitions of wisdom, on the other hand, are based on the layperson's understanding of the term. Implicit definitions therefore represent a population-wide understanding that is intuitive without necessarily knowing the sources for this understanding.

Explicit definitions of wisdom

The most prolific research into the construct of wisdom has originated from the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin, initially under the guidance of Paul B. Baltes. An explicit, developmentally based definition of wisdom, the Berlin wisdom paradigm, broadly frames wisdom as being a measure of expertise in the fundamental pragmatics of life (Baltes and Smith, Reference Baltes, Smith and Sternberg1990). This definition was conceptualized further as wisdom equating to good judgment and advice in those situations that have an element of uncertainty (Baltes and Staudinger, Reference Baltes and Staudinger1993). The five components of the Berlin wisdom paradigm include rich factual knowledge, rich procedural knowledge, life span contextualism, relativism, and uncertainty, with an individual's level of “wiseness” determined by how many components they exhibit.

One of the critiques of their work has been that it conceptualizes wisdom more as a form of intellectual development (Glück and Bluck, Reference Glück and Bluck2011) and as knowledge that is focused on expertise and intellect (Ardelt, Reference Ardelt2004). As a result, the definition may fail to encompass constructs such as those reflective and affective qualities that represent the more virtuous basis of the “personality” of a wise person (Ardelt, Reference Ardelt2004).

Sternberg (Reference Sternberg1998) also offers an explicit definition of wisdom, referred to as the balance theory of wisdom. This theory incorporates the use of tacit knowledge – when, where, how, to whom, and why to apply knowledge (Sternberg, Reference Sternberg2003) – that is mediated by a philosophy to create common good. The theory further involves a balance between intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extrapersonal interests, such that a balance between the need to adapt to, shape, and/or select an environment can occur. And so a balance is sought between the values of the individual and those of the community, within the context of the current environment. Brugman (Reference Brugman, Birren and Schaie2006) comments, however, that the balance theory of wisdom lacks the empirical evidence of the Berlin wisdom paradigm. Brugman (Reference Brugman, Birren and Schaie2006) also suggests that the idea of making decisions for the common good is too subjective.

Implicit definitions of wisdom

Clayton and Birren (Reference Clayton, Birren, Baltes and Brim1980) asked 83 people to judge how similar 14 wisdom descriptors were to the term “wise.” As a result of their analysis, three attributes were identified as capturing the multidimensional nature of wisdom – cognitive, reflective, and affective components. As the research is based on a small sample from an American university community, generalizability is questionable.

More recently, Glück and Bluck (Reference Glück and Bluck2011) had 1,955 participants rate eight items that described wisdom. Using cluster analysis, the authors proffered two groupings of respondents, those with a cognitive conception and those with an integrative conception. The cognitive conception grouping included the elements of knowledge and life experience, along with cognitive complexity. The integrative conception grouping included the same elements as those found in the cognitive conception, as well as elements around empathy and a love for humanity, which formed a greater component of the integrative conception. Self-reflection and acceptance of others’ values was also of the integrative conception, but not as strong a component as the affective aspects. Therefore, they identified an integrative conception highlighting cognitive, reflective, and affective aspects as defining wisdom implicitly. However, the participants were highly educated and were recruited via the German equivalent of a National Geographic magazine and so again, the generalizability of the definition may be limited.

Eastern-based implicit definitions of wisdom have not been explored as prolifically as those based in Western populations (Takahashi and Overton, Reference Takahashi, Overton, Sternberg and Jordan2005), potentially a result of wisdom research beginning in Western universities (Birren and Svensson, Reference Birren, Svensson, Sternberg and Jordan2005). For example, Yang (Reference Yang2001) contributed to conceptualizations of wisdom beyond Western orientations by exploring how Taiwanese Chinese conceptualize wisdom. Collating a list of the behavioral attitudes associated with being a wise person, Yang's (Reference Yang2001) results highlighted four factors: competencies and knowledge; benevolence and compassion; openness and profundity; and modesty and unobtrusiveness. In 2002, Takayama explored implicit definitions of wisdom within the Japanese population. A large study with 2,000 participants, the results supported four wisdom factors: knowledge and education; understanding and judgment; sociability and interpersonal relationships; and introspective attitude. Sung (Reference Sung2011) looked at how Korean older adults defined wisdom via a Q-methodology. Four types of wisdom were subsequently identified in this study: (1) experience-oriented action type; (2) emotion-oriented sympathy type; (3) human relationship-oriented consideration type; and (4) problem solution-oriented insight type. Research into Eastern conceptualizations of wisdom is therefore promising, and suggests the discovery of core features of wisdom that may be relevant regardless of culture.

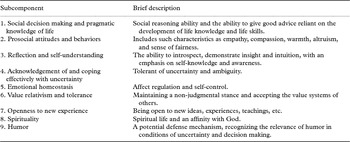

Bangen et al. (Reference Bangen, Meeks and Jeste2013) updated the earlier review of definitions of wisdom by Meeks and Jeste (Reference Meeks and Jeste2009) comparing 24 implicit and explicit definitions of wisdom. They included definitions from both Western and Eastern perspectives. Based on their review, they identified nine subcomponents (summarized in Table 1). Unsurprisingly, there was an overlap with the original review carried out by Meeks and Jeste (Reference Meeks and Jeste2009), with all six of the subcomponents identified in the original article also appearing in the most recent review. Bangen et al. (Reference Bangen, Meeks and Jeste2013) highlighted that the first five of their listed subcomponents were the most common, with the final four being included in less than half of the definitions reviewed. Of interest was that the subcomponent of value relativism and tolerance (proposed by Meeks and Jeste (Reference Meeks and Jeste2009) as a common subcomponent) was not noted as common in the more recent review, potentially reflecting the higher number of definitions reviewed by Bangen et al. (Reference Bangen, Meeks and Jeste2013).

Table 1. Common subcomponents of wisdom (Bangen et al., Reference Bangen, Meeks and Jeste2013)

Conclusion

Despite the main focus of definitional work in wisdom research to date being around segmenting Western and Eastern conceptualizations, much of that research, when considered together, highlights commonalities among those definitions. In particular, knowledge, understanding, and connecting with and considering others appear commonly within both cultural groupings of definitions. It may therefore be within those commonalities that the very core of wisdom is to be found. Rather than a focus on external sources of wisdom then, it may be that such core elements form the foundation upon which to promote the development of internal sources of wisdom through such means as therapy, for example. And through such development, resiliency and coping when faced with uncertainty in life circumstances may be enhanced. Significant steps toward support for such outcomes have already been undertaken, but there is room for further consideration and research in this area of study.

Conflict of interest

None.

Description of author's roles

Leander Mitchell wrote the editorial, and Bob Knight and Nancy Pachana edited the draft version.