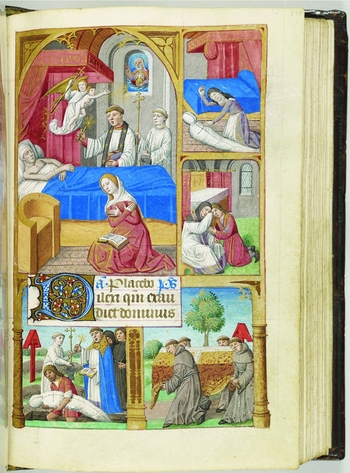

The image used to illustrate this editorial comes from a late medieval Book of Hours and shows some of the rituals related to death and burial at the time (Figure 1). For the Christian people of medieval Western Europe death was not only a common occurrence, but also one that was illustrated in many places in their lives. In their churches they would see sculptures of the Last Judgment above the front doors, a Dance of Death inside the back door, and along the walls funerary monuments. Above them were stained glass windows as well as altarpieces that might show the Death of the Virgin or other saints. At home there would be more panel paintings, as well as the illuminations of death-related rituals in the Office of the Dead in their books of hours, and the woodcuts of the Good Death in their Ars Moriendi books.

Figure 1. An image from the Book of Hours: MS M.231, fol. 137r. Paris, France, ca. 1485–1490.

Source: The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York.

While this death-related art from churches and prayer books of the late medieval and early renaissance periods (much of it now in museums and libraries) is often very beautiful, some is gruesome and was meant to frighten the viewer. Does this mean that medieval men and women were death obsessed? Without going into the detailed historical arguments for and against this proposition (Wieck, Reference Wieck, DuBruck and Gusick1999; Duffy, Reference Duffy2005), it is obvious from a study of the period that death was something that was likely to impinge on the consciousness of most people on most days. This was either because someone in their kinship group was dying or had recently died or because they were confronted by representations of death.

Would a daily reminder of death make those of us who care for old people in postmodern 21st century environments provide better care? Would the thought that death might occur for any of our patients on any day make us communicate more carefully with them and their relatives and friends, as well as consider judiciously the need for investigations and complicated therapies? Also most of the patients looked after by clinicians who work in Psychiatry of Old Age will have experienced the deaths of one or more of their close family members or friends, possibly recently. I suggest that an awareness of how these losses, with their accompanying grief plus their own concerns about death, might affect older people is part of the skill set needed to work in the field.

Perhaps a way of considering these issues is to ask if we can normalize death? And if we can, should we? We can define “normalize” as: “to make normal or regular” (OUP, 1973). The educated person (in the street) when asked about normalizing death might suggest those actions and beliefs that can help us to make sense of things that might otherwise overwhelm us. A member of Gen Y might say “making sense of serious stuff.” A Palliative Care colleague suggests that we can only help our patients and their families to normalize death when we understand the cultural, psychological, spiritual, and other elements of the deceased and the bereaved we are involved with, so we can understand the effect of death for those people and its effect on us. For all clinicians, but especially those who look after older people, the concept of normalizing death is the acceptance of the fact that we will all die and the incorporation of this into our clinical practice.

The following discussion of death-related images and the meanings to those viewing them at the time of their production may provide some ideas to assist us all in our considerations of death and its meaning to ourselves and our patients. The focus is on illustrations (in the broadest sense) from Christian late medieval Western Europe and 21st century Australia discussing the depicted actions of the dying and the bereaved in their attempts to normalize death for themselves. The principal change in the thinking and actions related to dying and death between these two times is a transition from worrying about the fate of the soul of the dead person to worrying about the fate of the mind of the bereaved person. These changes occurred over a long period of decreasing belief in an afterlife coupled with an increasing emphasis on the primacy of the feelings of the individual in any situation. Concomitant with the decrease in religious belief has been the increase in the belief of the power of medicine in the minds of the general public. As an aside, this belief in the power of medicine by members of the community causes those of us who look after the old and the dying to spend a lot of time preaching the medicine of diminished expectations.

One of the commonest types of the medieval images mentioned above is that of death in the midst of life. The three common instances of this of this familiar trope were: the Dance of Death, the three living and the three dead, and death and the maiden (which may be seen as a version of the three living and the three dead). In the latter two instances, this was often depicted as death appearing unexpectedly in front of the living who were represented out and about enjoying themselves. Death in these paintings and illuminations is often shown as a skeletal figure with an open abdomen or as an unfleshed skeleton, and both versions may carry a scythe or a spear (Rooney, Reference Rooney2011).

The Dance of Death is a strip like painting or illumination where Death invites individuals to join him in a dance from which there is no escape. Dances of Death appear both as wall paintings in medieval churches and in books of hours. Classic examples remain on church walls in Tallinn and Berlin, and in books of hours. The wall painting in Tallinn in Estonia has a fragment showing a Pope being approached by the two figures of death, one with a coffin, while a third death figure sits and plays the bagpipes, which were regarded as an instrument to wake the dead (Dance of Death; http://www.dodedans.com/Eest1.htm). The Pope is unsuccessfully attempting to avoid death's invitation to join the dance.

Such illustrations are described under the general heading of the quick (the living) and the dead. The three living and the three dead is another common example of this type. In these representations, the living are usually three well-dressed young men on horseback confronted by three dead men (shown as partial skeletons) who are usually on foot. An example in the Wharncliffe Hours (Manion, Reference Manion2005) shows the three young men so distressed by the apparition of the three dead men that their horses rear in fright and fall down. The legend was well known right across Europe by the end of the 13th century (Binski, Reference Binski1996). Death and the maiden is a variant on this theme, where a young woman is either shown looking into a mirror where she sees death behind her, or death embracing the young woman as seen in a vivid example by Gruning in the Kunstsmuseum in Basel (De Pascale, Reference De Pascale2007).

The purpose of these images on church walls and in panel paintings was to remind the viewer that death was omnipresent and needed prayerful consideration. The Ars Moriendi (the art of dying) provided a deeper and more personal way of considering death. In this devotional book, the emphasis was on dying well so that your soul went to heaven. The Ars Moriendi were designed for the laity so that they could achieve the desired “good death” even if there were no clergy present. The “good death” that was hoped for was one where the person dying recognized that they were dying and repented of any sins, so that their soul would not go to hell after death. Most Ars Moriendi are early printed works comprising a text accompanied by woodcuts illustrating the required steps in achieving the “good death.” The deathbed is shown as “an epic struggle for the soul of the Christian” (Duffy, Reference Duffy2005), with death standing at the foot of the bed pointing toward the dying person and the devil shown whispering in the dying person's ear. The final illustration shows an angel transporting the soul of the dead person to heaven providing a visual guarantee of the “good death” (Yvard, Reference Yvard2002).

The image of the angel transporting the soul of the recently deceased person occurs again in the illuminations accompanying the Office of the Dead in books of hours. These prayer books were the most personal items that late medieval Christians used when they considered death. Books of Hours are some of the most beautiful objects from the period because of the hand-painted illuminated pages and decorations around the text. The text comprised the offices or “hours” that were either the same as or similar to those recited by the clergy of the time, particularly those in monasteries. Books of Hours were developed as the laity became more literate and more desirous of having their own prayer books. Almost all Books of Hours contain the Office of The Dead, “at the back of the book as death was at the back of the medieval mind” (Wieck, Reference Wieck1997).

The Office of the Dead was prayed over the deceased, between death and burial, and was recited daily in monasteries and churches, using the same text as that in the books of hours. The Office was originally called the Office for the Dead because the prime function of performing the office was to gain the release of the souls of the dead from purgatory. An understanding of purgatory as the place in the afterlife for those who were not good enough to go directly to heaven, but not bad enough to go to hell after death, is necessary to understand late medieval Christian thinking about death. Once the soul of the dead person had spent enough time in purgatory then it would go to heaven. The souls in purgatory could do nothing to help themselves; however, those left on earth could recite the Office of the Dead, attend mass, and give alms to the poor to expedite the progress of souls through purgatory. Money was left in wills for almsgiving and especially to pay monks to chant the office and for priests to say masses for the soul of the testator, sometimes in Chantry chapels built expressly for this purpose (Daniell, Reference Daniell1997).

The range of illustrations used to accompany the text of the Office of the Dead is both broader and quite different to those in other parts of the same Book of Hours. There are many fewer representations of Biblical scenes and many more of illustrations of the common death-related rituals of the period. The illustrations are so real that from them we can piece together the full set of religious and domestic events that occurred from dying to burial with “what might be called archeological, accuracy” (Wieck, Reference Wieck, DuBruck and Gusick1999). Not only do these illuminations show us the types of rituals that occurred in relation to death, but they also show us how the people of the time behaved in these situations.

In the illumination used to illustrate this editorial, the widow prays calmly from her Book of Hours not even looking at her newly dead husband. The woman who sews the body into a shroud does so practically and respectfully and the scenes of confession in church, procession to the grave and burial, show all those involved behaving reverently while fulfilling the familiar and required rituals, so that by their reverent praying the soul of the person would go to heaven. The protagonists are shown wearing their best clothes or the appropriate robes of their office. We know their prayerful performance of the rituals was successful because we see the soul of the dead man being taken to God by an angel, while evading a small devil below.

I consider that these illuminations in books of hours of familiar although sad scenes would have helped those who used their books daily to normalize death. The calm behavior in the midst of death assisted those viewing the scenes to make sense of the deaths of loved ones. The use of the Book of Hours to pray for the dead entailed viewing the illuminations of death and funerals, combined with the repetition at home of the chants of the monks over the dead body in the coffin. In the context of the universal belief in the efficacy of prayer for the dead in releasing the souls of the dead from purgatory, these actions would have assisted in this normalizing process.

When we consider the commentaries about death and the death rituals of the 21st century we are immediately aware of a very different set of beliefs and behaviors. There has been a major change in the understanding of those in the developed world about what a “good death” comprises from a model where religion was the dominant framework to one where medicine dominates (Walter, Reference Walter2003). In that change, we initially lost the knowledge of diagnosing dying that was a normal part of medieval life (Daniell, Reference Daniell1997). Only now are we beginning to understand that we first need to recognize that a person is dying before we can facilitate a “good death” (Ellershaw and Ward, Reference Ellershaw and Ward2003).

The “good death” for the 21st century has been categorized (Smith, Reference Smith2000) in a paper where the issues discussed are a set of middle class, baby boomer statements. The main prerequisites for a “good death” are controlling when, where, and how death will happen, choosing who will be there, and what they will say and do. This “good death” includes the expectations that pain and other symptoms will be controlled, and appropriate and desired spiritual care will be available with all other necessary expertise. While these aspirations are a step in the direction of better recognition, and care, of the dying, they are not a realistic option for the majority of people dying in the nursing homes and other aged care facilities of urban Australia in the 21st century, let alone for those dying in the rural third world (Kellehear, Reference Kellehear2001).

What images come to mind when we consider death in the 21st century? We are no longer bounded by the geography of our medieval ancestors so we can be “involved” in the deaths and funerals of people not personally known to us and in another country, an obvious example being the death and burial of Diana, Princess of Wales. Images of her death and funeral were such prominent items in all media that many of us can “see” the flowers outside Kensington Palace, or her sons walking to Westminster Abbey, though she died in 1997. Images of those who have died in major disasters, both naturally occurring and man made, may come to mind when we consider how death is portrayed in our world.

Apart from the representation in the print and electronic media of those who have died, many of the other death-related images of our time are found online. The ubiquitous web blurs the distinction between public and private with many of what would once have been considered personal responses now made public, for example a Spanish teenager blogging about the death by murder of her parents. In Australia, young people who die in road traffic accidents have their Facebook pages updated by their friends after their deaths. Twenty years ago the sites of their death would have been covered in floral tributes and while these still occur they are less prominent today (Roadside Memorials; http://australianmuseum.net.au/movie/Roadside-memorials).

A quick trawl through a group of websites with death or grief in the title finds many that offer assistance with grief and the personal experiences of death and dying, as well as those that offer a permanent memorial, complete with photographs of the deceased, rather than the ephemeral ones of the daily newspaper. Other websites purport to tell you when you will die (http://www.deathclock.com) and/or inform you whether someone famous is already dead (www.deadoraliveinfo.com).

Having considered the images of death in our time, I will discuss some of the images of funerals. Depending on whether we have attended (a family or other personal) funeral recently, the ones that come to mind might be those of famous or unfortunate people whose funeral becomes a public event. Public funerals in Australia tend to follow the very old Christian rituals even when the deceased was not a believer, being set in a church and having presiding clergy and mourners dressed in their best black or appropriate official robes. In Australia, although we are a multicultural society with a multitude of different expectations of and understandings about death, when it comes to public rituals the dominant Anglo Celtic culture very often overrides any personal beliefs, or lack of beliefs, of the deceased.

While we might consider that it is only in the late 20th and early 21st centuries that we have been able to “do our own thing” in relation to death and burial rituals, Ariés suggests that mourning became spontaneous in the 19th century and that conventions were done away with then (Ariés, Reference Ariès1976). However, we view that statement for most of us in post Christian Australia and it is really only in the last 50 years that funerals have been able to be personalized to any degree. Those where the person dying and the family can make their own arrangements are much more likely to be unique, even when based on a religious framework.

In truly secular funeral services the ritual is often a series of recitations of the life of the deceased, including the memories and concerns of the bereaved. Films and other media files of the deceased will be shown, including messages from the deceased to the family and others, music chosen from the deceased's playlist, with the possibility of a customized coffin and hearse. Cremation is the commonest form of disposal of the body after death in Australia and many cremations are conducted with either only close family present, or no members of family or mourners present at all. The wearing of black is not imposed and sometimes those attending are encouraged to wear the person's favorite color. Crying and displays of emotion are expected, particularly when the deceased is young, and/or the death was sudden and unexpected.

Some of the images I have discussed may resonate with both clinicians and their older patients and clients and their families. I hope this discussion of some of the visual aspects of death and burial rituals in the late medieval European context and the 21st century Australian setting has encouraged you to think about how your older patients and their families may view death, and what sort of beliefs and expectations they might have about their own death and burial rituals. This quote from a recent film on dying, death, and palliative care – “dying is not a medical event, it is a human experience” (Life Before Death; http://www.lifebeforedeath.com/movie/short-films.shtml) – reminds us all to consider all the concerns of our patients not just their overtly clinical ones.

Conflict of interest

None.