Summary

Shared decision making (SDM) is an important part of achieving the safety and quality of use of medications. Most studies on SDM have been conducted in general practice and are from the perspective of health care professionals and individuals who are in control of making decisions. This is the first study to explore long-term care facility (LTCF) residents’ perspectives of SDM in medication management. This study highlights that residents’ beliefs in having control over decisions and concerns about medication are key factors influencing overall SDM processes. Therefore, it is important to understand residents’ beliefs and values regarding their role in medication decisions to address any misconceptions and strengthen participation.

Introduction

Older people living in long-term care facilities (LTCF) have multimorbidities and are susceptible to geriatric syndromes and take multiple medications (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison2018b; Inouye et al., Reference Inouye, Studenski, Tinetti and Kuchel2007). Furthermore, there is a high prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) use, that is, where the actual or potential harms of therapy outweigh benefits, in older adults in LTCFs (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison2018a). These factors have been associated with increased risk of adverse drug effects in residents, including hospitalizations, lower quality of life, and mortality (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison2018a; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Dyer, Lawlor and Kennelly2020). In the field addressing PIMs, shared decision making (SDM) is recognized as important in achieving appropriate use of medicines, including initiation, ongoing use, and deprescribing (rational withdrawal of medications) (Jansen et al., Reference Jansen2016; Reeve et al., Reference Reeve, Thompson and Farrell2017) and has become part of the gold standard in facilitating resident-centered care (Polypharmacy Model of Care Group, 2018).

Shared decision making is the process in which both the person, their representative, and health care professional share information with each other, take steps to participate in the decision-making process, and agree on a course of action (Charles et al., Reference Charles, Gafni and Whelan1997; Sheridan et al., Reference Sheridan, Harris and Woolf2004). There are various models of the SDM process: in some models, the process is left to the discretion of the individual and health care professional, while other models define specific steps that may differ. For example, many acknowledge the patient’s right to relinquish the decision to the health care professional and proceed in a paternalistic model (Charles et al., Reference Charles, Gafni and Whelan1997; Sheridan et al., Reference Sheridan, Harris and Woolf2004). Other models require discussion of the benefits and harms of treatment (Charles et al., Reference Charles, Gafni and Whelan1997; Légaré and Witteman, Reference Légaré and Witteman2013; Mariani et al., Reference Mariani, Vernooij-Dassen, Koopmans, Engels and Chattat2017).

Most studies that have identified barriers and facilitators to implementing SDM have been conducted in general practice and are from the perspective of health care professionals and patient representatives (Légaré et al., Reference Légaré, Ratté, Gravel and Graham2008; Mariani et al., Reference Mariani, Vernooij-Dassen, Koopmans, Engels and Chattat2017). For example, primary care physicians described time restraints and lack of familiarity with SDM as barriers, while their perceived applicability of SDM based on patient characteristics influenced the adoption of SDM (Légaré et al., Reference Légaré, Ratté, Gravel and Graham2008). The majority of older adults prefer to share decisions with their primary care physicians about their health care (Chewning et al., Reference Chewning, Bylund, Shah, Arora, Gueguen and Makoul2012; Wolff and Boyd, Reference Wolff and Boyd2015) and would like to be involved in making decisions about their medications (Reeve et al., Reference Reeve, Low and Hilmer2019). However, decision making becomes more complex for older adults living in LTCFs as they have multiple comorbidities, experience decline in decision making abilities, and require complex care needs (Vetrano et al., Reference Vetrano2013). Studies conducted in LTCFs that investigated SDM from the perspective of residents focused on advance care planning, transfer to the emergency department, and use of hip protectors and feeding options (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Schiowitz, Rait, Vickerstaff and Sampson2019; Ervin et al., Reference Ervin, Blackberry and Haines2017). At present, very little is known about SDM in medication management from the perspective of LTCF residents.

This study is part of a larger study exploring LTCF organizational culture related to psychotropic medication use (Sawan et al., Reference Sawan, Jeon and Chen2018; Sawan et al., Reference Sawan, Jeon, Fois and Chen2017; Sawan et al., Reference Sawan, Jeon, Fois and Chen2016). The study found that aspects of organizational culture influences health professionals’ decisions to use psychotropic medications. Aspects of culture included staff feeling they had an external locus of control, believing they were helpless to do the right thing by the resident due to perceptions of limited resources (Sawan et al., Reference Sawan, Jeon and Chen2018). The study reported variation in how LTCFs engaged with residents’ families in care decisions through routine processes, such as the use of case conferencing (Sawan et al., Reference Sawan, Jeon, Fois and Chen2016). Importantly, some primary care physicians and LTCF staff acquiesced to requests from residents, or their representatives, for the continuation or initiation of psychotropic medications without discussing the potential harms or benefits of treatment (Sawan et al., Reference Sawan, Jeon, Fois and Chen2016). Therefore, it is also important to explore the perspectives of residents on SDM in medication management, particularly when treatment decisions are strongly influenced by the residents’ (or caregivers’) beliefs and values on medication (Bourgeois et al., Reference Bourgeois, Elseviers, Azermai, Van Bortel, Petrovic and Vander Stichele2014; Smeets et al., Reference Smeets2014). In this study, we used the term SDM as a broad principle to assist in medication management in LTCF, rather than the individual steps of SDM.

The aim of this study was to explore the concept of SDM in medication management from the perspective of residents of LTCFs. The objective of this study was to identify residents’ beliefs, motivation, and aspects of the environment that facilitate or impede SDM.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

A qualitative inquiry using face-to-face semi-structured interviews was conducted to understand the complex processes that influence resident participation in SDM in medication management (Charles et al., Reference Charles, Gafni and Whelan1997). Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol No. 2012/401) prior to commencement.

In Australia at the time of recruitment to this study, LTCFs were classified as low care or high care or both. Low care LTCFs provide accommodation and low-level nursing care. High care LTCFs offer care for people with greater frailty and need for 24-h nursing care in addition to low care needs. Purposive sampling at site level was used to reflect these diverse levels and type of care in LTCF. The interviews were conducted in LTCFs that were all located within the greater metropolitan area of Sydney from September 2015 to February 2017. Following organizational consent, staff of those consenting LTCFs facilitated the recruitment of potential participants. The participant inclusion criteria were residents who could express their views and experiences in English. Participation was voluntary, and written informed consent to participate in the study and to record interviews was obtained from participants. Interviews took place until saturation whereby additional interviews did not yield any new insight relevant to the study, and judgment was made using field notes as well as interview transcripts (Morse, Reference Morse1995).

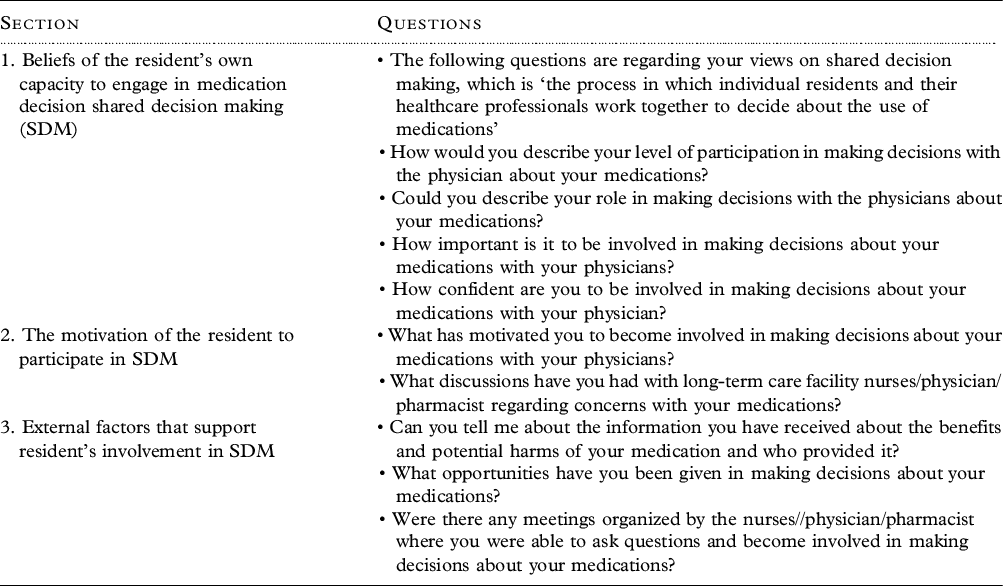

The semi-structured interview guide (Table 1) was developed from the definition of SDM and a comprehensive systematic review on the barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision making (Légaré et al., Reference Légaré, Ratté, Gravel and Graham2008; Légaré and Witteman, Reference Légaré and Witteman2013). Prior the interview, the purpose of the interview and the concept of shared decision making were explained to residents. Shared decision making was explained to participants as the process in which individual residents and their healthcare professionals work together to decide about the use of medications (Charles et al., Reference Charles, Gafni and Whelan1997). The interview guide comprised sections to examine key elements which influenced the adoption of SDM, as identified in the systematic review. These were the beliefs of the residents’ own capacity to engage in medication decision, the motivation of residents to participate in SDM, and external factors that support residents’ involvement in SDM. Participants were asked open-ended questions. For example, How important is it to be involved in making decisions about your medications with your physicians? What has motivated you to become involved in making decisions about your medications with your physicians? What opportunities have you been given in making decisions about your medications? (Table 1). Medication management encompassed the initiation, continuation, and cessation of treatment. The interview guide was piloted to ensure that it was clear and comprehensible and that the time taken to complete the interview was reasonable. No amendments were deemed necessary after pilot interviews with two residents, which were included in the study.

Table 1. Interview guide

These were some of the questions that were asked of the participants. Interviews were conducted one-on-one, in a private area in the absence of facility staff, and by a trained research team member.

Analysis

All interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, reviewed for accuracy by examining transcripts multiple times while simultaneously listening to recordings and entered into a qualitative software program (NVivo, version 12). Data analysis was initially carried out using a thematic approach to identify themes that emerged from the data that answered the purpose of our inquiry (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006; Patton, Reference Patton2002). The transcripts formed the data set, and the first author (MS) created codes to label experiences around participation/non-participation in SDM. Then authors (MS, TC, and YJ) developed and refined codes to identify themes for resident’s general beliefs, motivation and perceptions of external factors influencing participation in SDM. The research team (MS, TC, and YJ), using analyst triangulation, then established and refined coded categories to arrive at subthemes around residents’ beliefs, motivations, and perceptions of external factors. The research team met frequently to review samples of transcribed data and discuss emerging themes. These were reviewed and refined to reconcile differences in interpretation until no new themes emerged, and all researchers agreed on the final interpretation of the data.

Results

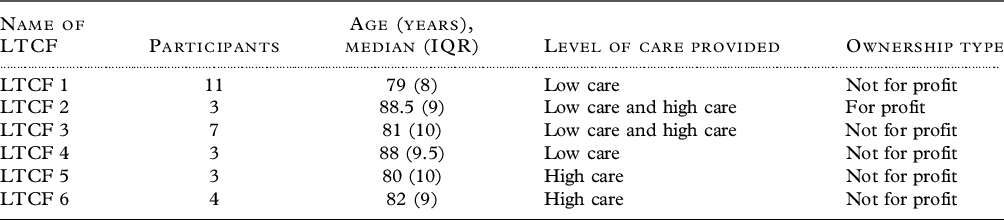

Thirty-one residents from low (n = 2), high (n = 2), and combination of low/high care facilities (n = 2) were interviewed. Table 2 summarizes LTCF characteristics. The median age of residents who participated was 85 (IQR 6) and most were female (n = 23). The age range was 66–92 years. All the interviews were conducted at LTCFs. The median duration of the interviews was 23 minutes (IQR 10).

Table 2. Characteristics of long-term care facilities (LTCF)

Out of the 31 participants, five reported to have been engaged in SDM about medication management. This study identified three main themes describing the barriers and facilitators to resident involvement in SDM for medication management: 1) residents’ belief toward participation in medication decision making; 2) residents’ beliefs about medication; and 3) external factors that impact on residents’ participation in SDM.

Resident participation in medication decision making was influenced either by deferring control/participation or exercising the right to control/take part in medication-related decisions. Residents’ beliefs about medications pertained to their perceived need for medications versus concerns about harm. External factors which influenced residents’ participation in SDM were related to the behaviors of LTCF staff and primary care physicians, such as respecting the residents’ right to participate in SDM, attentiveness to residents’ concerns, and providing residents access to continuity of care.

Residents’ actions toward participation in medication decision making

Two possible residents’ actions that influenced involvement in SDM were identified: Deferring control or participation in medication-related decisions to others and exercising the right to control or take part in medication-related decisions.

a) Deferring control or participation in medication-related decisions to others

A majority (n = 19) of participants perceived to have no capacity to make decisions with regard to their medications due to having limited knowledge and understanding of their condition and treatment. Therefore, these participants believed they could not actively contribute to discussions with health professionals about medications and preferred to rely on experts/authority figures such as the primary care physician, nurse, or their representatives to make medication-related decisions. In addition, a number of participants reported that their capacity to understand complex information needed to make decisions was further hindered by various circumstances such as declining health and cognition, forgetfulness, and technical jargon. For this reason, they resigned not to be involved in medication-related discussions.

What is the good of having these discussions? You can’t remember. I forget. The doctors see all this, my daughter-in-law gets involved. A lot of people worry about it, I don’t. (Participant 2, Female, 85 years, combination of low/high care)

Within this category, some participants adopted a passive role in medication-related decisions due to the beliefs that the primary care physician and nurses were authority figures that could not be questioned, which acted as a barrier to SDM. This perceived patient–physician role resulted in the resident resigning all decisions to the physician.

I don’t know a great deal at all; I just take them. I don’t know about them except they taste like poison. I place all my trust in the doctors, and I feel they know what I need more so that I do what I’m told, and I’m guided by them. (Participant 3, Female, 86 years, high care)

Several participants ascribed polypharmacy to be a characteristic of old age and were resigned to the belief that polypharmacy was the norm. The approach to managing polypharmacy was to “bear it” rather than participating in discussions with a health professional or requesting information on how to reduce the number of medications.

I’ve got a lot [of medications]. To me, it’s just another sign of getting older, which doesn’t thrill me to bits.… I’d like it to be less. Love it be less, but if I need that many, I need that many and I’ve got to take them and bear with it. (Participant 4, Female, 80 years, combination of low/high care)

Designating medication-related decisions to health professionals resulted in a number of participants not actively seeking information or engaging in discussions regarding medications. Some participants described relying on their families to obtain information from primary care physicians and specialists and engage in discussions on their behalf. A number of participants relayed having concerns with their medications, such as polypharmacy, however, did not participate in decision making because they were not aware of their right to do so or did not want to be labeled as difficult residents.

You don´t get that option to be involved. So, you just got to do what you do. The staff give you the medication, you´ve got to take it. (Participant 27, Male, 79 years, low care)

b) Exercising the right to control or take part in medication-related decisions

Participants (n = 12) perceived that they could maintain their right to participate in medication-related decisions, including those who acknowledged having limited English, lacking health literacy, and poor health. The belief in having the ability to take part in decisions was manifested in residents who reported the need to advocate for themselves and voice their preferences to maintain control over their health and function. For this reason, they wanted to be involved in medication-related decisions and sought information regarding medications.

I make decisions. See, I´m not senile yet. Yeah, I´m not an idiot. And I tell him [the doctor] that too. He explains what benefits there is and things like that. If I don´t know what he´s talking about, I just ask him. I´ll say explain; I don´t know what you´re talking about. And he does. (Participant 9, Female, 82 years, low care)

Some participants felt that it was acceptable to question the primary care physician regarding medication-related decisions because they believed they had more knowledge of themselves than the physician did and that they had control of their own body. These participants raised conversations regarding medication with the primary care physician, asked questions, and sought out information even when they perceived that it might risk losing favor with the physician.

I’m the type of person I drive doctors mad. I want to know what’s that for, how does it work, the name of it. Even in here [the LTCF]. ‘What’s that for?’, if they give me something new. ‘Explain’. They have to; I won’t take it otherwise. This is my body, anything going in here is going in my body. (Participant 10, Female, 89 years, combination of low/high care)

Residents’ beliefs about medications

Residents’ beliefs about medications related to residents’ perceived need for medications versus concerns about harm that motivated them to take an active role in SDM.

a) Perceived need for medications over concerns about harm

Some participants (n = 7) were not motivated to participate in medication-related discussions with their primary care physician or acquire information about their medications because they perceived their medications were beneficial and not causing apparent harm. A number of participants believed that they did not need to discuss their medications because they did not experience side effects and/or because they had been taking medications for a long time.

I don’t know what the tablets are for. I’m all right. They’re not making me sick. That’s it. (Participant 11, Female, 87 years, low care)

I don´t need to discuss medicines with my doctor, cause I´ve been taking them virtually all my life. (Participant 7, Male, 79 years, combination of low/high care)

A few participants felt satisfied to remain on multiple medications as they believed continuation of medication was required and would not cause any harm. In addition, they acknowledged the need for treatment was related to their fear of what might happen without medication, such as symptoms would return, and awareness of other residents who had trialed cessation and were unsuccessful.

I’ve got myself down to about one tablet of Valium (diazepam) at one stage. [The doctor] said you’re on such a tiny dose now, you could probably get right off if you want to and back on if you want to. I could get off it but then I’d have to go back on it again, and I didn’t like the idea of that and it does give me a good night’s sleep and not many people can stop it. (Participant 12, Female, 79 years, high care)

b) Concerns about harm over perceived need for medication

A number of residents (n = 9) were motivated to raise their concerns about medications with their primary care physician. Residents’ medication concerns included wanting to stop medications due to experiencing possible side effects or a review of medications due to the belief that they were taking too many. In some cases, the primary care physician explained the risk versus benefit of medication, and the discussion resulted in arriving at a shared decision to withdraw medication.

I know what I can, or I can’t have. I was taking Tramal (tradamol) I had nightmares for three nights. The doctor explained that with Tramal (tramadol) you can get highs and lows…and you can be up one minute, up like kite and the next minute you’re down….and I didn’t want that so it was stopped immediately before they did any harm. (Participant 13, Female, combination of low/high care)

Other residents reported that they had raised concerns about medications with the physician; however, there was limited to no discussion about the harm versus benefit of medication.

I’m on Pradaxa (dabigatran), which I must take. But If I’m not careful with the Pradaxa, I get indigestion. I said to the doctor “do you think I could stop taking that, do I need it?” he said, “If you want to go on living, yes” I said, “oh”. He explained it’s a heart tablet, I’m in atrial fibrillation all the time. (Participant 14, Female, 80 years, combination of low/high care)

External factors that impact on residents’ participation in SDM

External factors that impacted on residents’ participation in SDM concerned the opportunities that made it possible for residents to partake in SDM. These were LTCF staff and primary care physicians respecting the residents’ right to participate in SDM, attentiveness to residents’ concerns, and providing residents access to continuity of care.

a) LTCF staff and physicians respecting residents’ right to participate in SDM

Across LTCFs, the majority of participants reported that there was limited opportunity to engage in SDM in medication management when they first entered the facility. However, there were distinctions between LTCFs in how they responded to residents’ requests to discuss medications. Some LTCFs provided clear pathways for residents to communicate concerns raised by the resident during their stay.

You don´t get that option. You just got to do what you do. They give you the medication, you´ve got to take it. (Participant 7, Male, 79 years, combination of low/high care)

They give us a meeting if you have any complaints, any problems. But [the RN] encourages for us to come see her in the office. She’s very good. And, her assistant, she’s also very good. (Participant 20, Male, 88 years, low care)

Some participants reported instances where the physician exercised the residents’ right to be involved in SDM by explaining the harm versus benefit of medications, including residents who were satisfied to not engage in medication-related decisions. For example, one resident, who felt it was not their role to discuss medications with the physician, reported that the physician explained the harm/benefit of continuing with medication for insomnia. As a result, the resident agreed to withdraw treatment for insomnia.

I take it for granted. I put my trust in the doctor. When I do, he’s got to be a qualified doctor if he knows about the medicines…I had a problem with insomnia, but I’m resisting taking tablets. I don’t want to take tablets. My doctor told me that they work for the short-term but in the long-term, they are not very efficient. So, I resist taking them. (Participant 5, Male, 69 years, low care)

Several participants (n = 5) reported that they would have liked to take part in medication-related decisions and share the decision on continuation of medication with the physician and other staff. However, they perceived that they were not given the opportunity during consultations with the physician.

I take ten tablets I have in the morning and six with the evening meal. I would like to be able to take less. I did mention months ago to the doctor, you know if I could take less, and he said, no, that I needed all the ones that I’m taking. I kept taking them. I thought ten is a lot. I wonder if any can be cut down on, but he said no. (Participant 15, Female, 89 years, combination of low/high care)

b) LTCF staff and physician’s lack of attentiveness to residents’ concerns

A number of participants reported experiencing open communication with the physician, which facilitated discussions about medications. The physician was reported to take into account the resident’s preferences and expressed needs concerning medications.

The doctor here is very good you can talk to him, it makes a difference. I said when I walk my feet feel numb underneath and he said, I’ll cut you down in your basic tablets. (Participant 17, Female, 89 years, low care)

Several participants reported limited engagement with physicians and staff to ask questions, raise concerns, and discuss issues related to medications. Poor communication of physicians and staff, such as not listening carefully to their concerns and poor delivery of complex information, was mentioned by residents. Participants perceived the lack of communication was due to physicians and staff being too busy due to the high workload and limited time.

The Doctor. He floats in and out. He just wants to get away. And that gets to me. We´re not important, you know. You can´t ask questions because you don´t get the answers. (Participant 18, Female, 77 years, low care)

I told the doctor that I´m sick of taking all these tablets, he said, “Well, they´re keeping me alive, aren´t they?” And I said, “Yeah, I suppose so”. (Participant 9, Female, 82 years, low care)

c) Access to continuity of care

Some residents reported that they did not have an option to continue care with their regular primary care physician upon entry into the LTCF and that the lack of continuity was a barrier to participation as they were not known by the physician. Other residents reported that they were given a choice to remain with their doctor and this facilitated trust with the physician.

When I came here [LTCF], and started complaining about my arthritis, I asked about my doctor but I found out I can’t have my doctor from outside because my doctor was not employed here [LTCF]. (Participant 19, Female, 80 years, combination of low/high care)

Several participants perceived that involvement of multiple specialists (external) in their care was a barrier to SDM because it made it difficult to navigate varying information from different specialists and created uncertainty. Also, residents who wanted to participate in shared decision making did not know how to share their preferences when different medical practitioners were involved.

You can´t ask questions because you don´t get the answers. I asked questions about my treatment. I´ve been treated for Parkinson´s for five years, I see the specialists over at the Hospital. The cardiologist increased my heart medicine and when I went to the hospital, the doctors said, “No, it´s too much”. So, they took me off it again. So, who are you supposed to believe? And the [LTCF] Doctor will say, “Oh, I´m not getting involved in that”. (Participant 9, Female, 77 years, low care)

Discussion

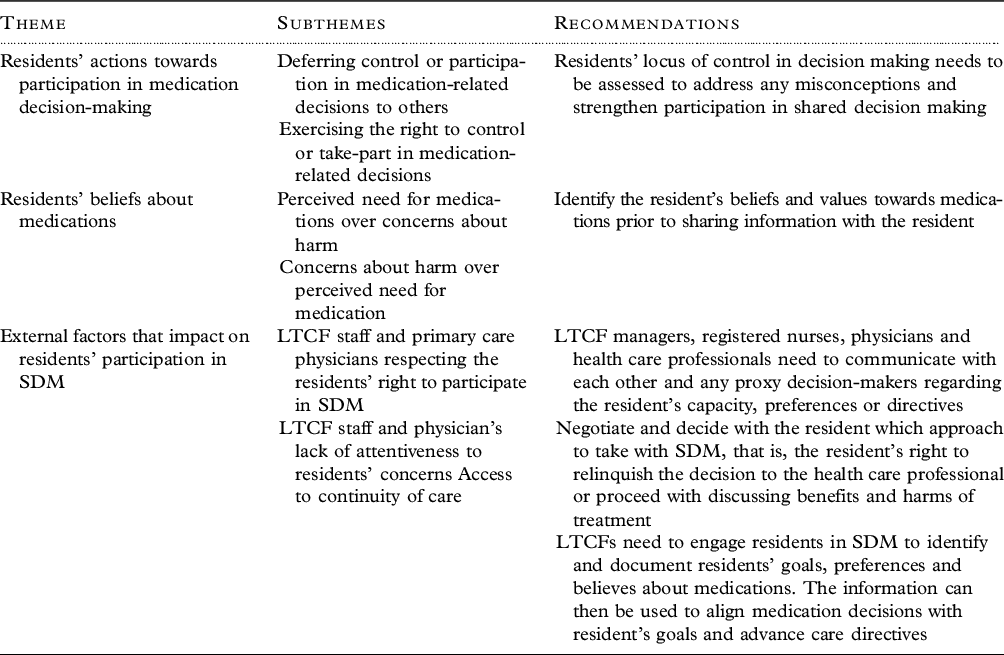

Shared decision making is considered an important part of person-centered care and optimization of medications in Australia and internationally (Australian Government Department of Health, 2018; Jansen et al., Reference Jansen2016; Polypharmacy Model of Care Group, 2018). This study is the first study to explore residents’ perspective of SDM in medication management and explains residents’ beliefs, motivation and external factors that facilitate or impede their involvement. Recommendations for SDM in LTCFs were identified from the study findings with support by broader literature outlined in the discussion and summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Recommendations for shared decision making in long-term care facilities identified from study findings

One such barrier to SDM was residents’ assessment of their own capacity that they could not contribute to decision making. Older patients with poor health, cognitive impairment, limited self-efficacy, and lower level of education are reported to feel vulnerable, which hinders their participation in shared decision making (Charles et al., Reference Charles, Gafni and Whelan1997; Joseph-Williams et al., Reference Joseph-Williams, Elwyn and Edwards2014). However, this present study showed that the resident exercising their right to control or take part in decision making may influence their motivation to participate in SDM. This aligns with the individuals’ internal/external health locus of control (HLOC) in decision making (Wallston et al., Reference Wallston, Wallston and DeVellis1978). In a UK survey of patients in general practice, low preference for involvement in SDM was significantly associated with higher external HLOC and higher age (Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Korner, Mehring, Wensing, Elwyn and Szecsenyi2006). Some studies show that the variability in the individual choice to participate in shared decision making could be due to the person’s age, the older the patient, the lower the desire for shared decision making, but this finding is not consistent (Joseph-Williams et al., Reference Joseph-Williams, Elwyn and Edwards2014). Age may be one of many interacting factors contributing to the person’s beliefs about their decision-making capacity. Before establishing residents’ preference to participate in SDM, it is important to assess their misconceptions about locus of control (Table 3).

Another important factor to SDM was the residents’ beliefs about medication, the perceived need for medication or concern about harm. For some participants, the preference to not participate in SDM was related to their belief that their medication was working or not causing them harm. Additionally, a number of residents wished to remain on medication although health professionals engaged residents in shared information because of the perception that they needed medication or feared that symptoms would return if they underwent withdrawal. Older adults beliefs about medications may vary depending on the type of medication (Reeve et al., Reference Reeve, To, Hendrix, Shakib, Roberts and Wiese2013). For this reason, it is important to identify the resident’s beliefs and values toward medications, particularly for residents who are ambivalent, prior to sharing information with the resident (Table 3).

Several studies highlight that physicians report challenges to engage patients in discussion on the risk and benefits of medication due to the lack of clear guidelines and limited evidence on deprescribing (Sawan et al., Reference Sawan2020; Schuling et al., Reference Schuling, Gebben, Veehof and Haaijer-Ruskamp2012). In addition to these barriers, this study showed the limited recognition of residents’ autonomy and choice are unique challenges to the adoption of SDM in LTCF setting. Some residents expressed a preference to participate in SDM, however, were hindered by the limited recognition for residents’ right to be involved in SDM from LTCF staff or physician. Therefore, an important step to SDM is to negotiate and decide with the resident which approach to take with SDM, that is, the resident’s right to relinquish the decision to the health care professional or proceed with discussing benefits and harms of treatment (Table 3).

Shared decision making involving residents in LTCFs with changing levels of cognitive abilities can be complex in relation to upholding their right to choose, including the preference to refuse care, and health professionals preserving their duty of care (Hurst, Reference Hurst2004). This applies to residents receiving health care consistent with their preferences stated currently if the resident is competent to do so, or previously through an advance care directive and/or surrogate decision maker to advise on what the patient would have wanted (Pirotte and Benson, Reference Pirotte and Benson2022). Surrogate decision makers, such as families, are important contributors to prescribing decisions. Therefore, the approach to SDM needs to include a discussion with a surrogate decision maker/caregiver if the person cannot engage in SDM themselves (Table 3). Also, LTCF staff and health care professionals need to communicate with each other and any proxy decision makers regarding the resident’s capacity, preferences, or directives (Hurst, Reference Hurst2004; Pirotte and Benson, Reference Pirotte and Benson2022).

This study highlights the key mechanisms behind the residents’ preference to engage in SDM with health professionals and how the LTCF environment is perceived to create opportunities for SDM. Residents’ preference for SDM varies, some are motivated to take an active role and others defer the decision to the health professional. In both cases, the support and encouragement of the residents to share their views at a level which they feel comfortable can facilitate residents’ engagement in SDM. Health care professionals recognizing and acknowledging that a decision is required is a key essential element in SDM (Légaré and Witteman, Reference Légaré and Witteman2013), which applies to residents in LTCF as well. Implementation of SDM requires a total acceptance by LTCF managers, registered nurses, primary care physicians, and other health professionals that residents have a role in treatment decisions (Table 3). From the perspective of LTCF staff, a reported barrier to SDM was staff not knowing how to lead conversations with resident and their representatives regarding the harms versus benefits of high-risk medication (Simmons et al., Reference Simmons2017). As such, LTCFs need to be proactive and take up measures, including education and training of staff and health professionals to engage residents in SDM to identify and document residents’ goals, preferences, and believes about medications. The information can then be used to align medication decisions with resident’s goals and advance care directives (Table 3).

Other barriers to shared decision making in medications were the residents’ limited access to continuity of care and staff and health care professionals being too busy. In this study, for some residents, the lack of motivation to engage in SDM was underpinned by the perception that the LTCF was paternalistic, illustrating that barriers to shared decision making are not limited to the patient–physician relationship, but the culture of the LTCF as well. Evidence from the literature suggests that medication management in LTCF is suboptimal due to limited resources contributing to high-level workload and time pressures on staff and health care professionals (Sawan et al., Reference Sawan, Jeon, Fois and Chen2017). The care demands also have implications on opportunities for LTCF staff and health care professionals to spend time with the resident to engage in authentic SDM. It is important for resources to be allocated to support the implementation of SDM and that existing national policies provide LTCF and health care professionals incentives to engage in SDM.

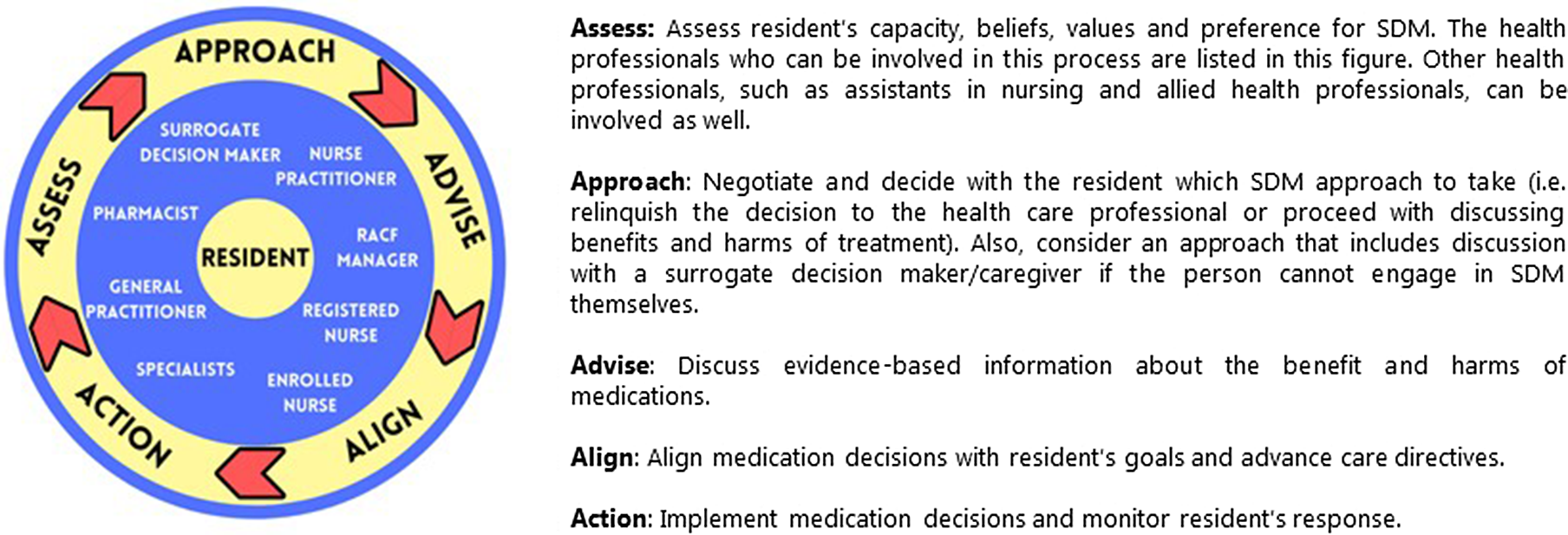

Based on the findings of this study, we propose a framework for SDM in medication management for residents to guide implementation in LTCFs (Figure 1). The framework incorporates five steps that align with the recommendations outlined in Table 3. The 5 steps of the SDM framework in LTCFs are Assess, Approach, Advise, Align, and Action. The process begins with an assessment by a health care professional of the resident’s capacity, beliefs, values, and preference for SDM. This step involves explaining to the resident and surrogate decision maker what SDM is, exploring the resident’s thoughts regarding participation, and identifying and addressing any misconceptions. The health care professional then works with the resident and surrogate decision maker to decide which SDM approach to take, i.e., relinquish the decision to the health care professional, or proceed with discussing benefits and harms of treatment. If the resident and surrogate decision maker decides to engage in SDM, then evidence-based information about the benefit and harms of medications is discussed with the health care professional. This step could also be conducted with a team of healthcare professionals. Importantly, medications are aligned with resident’s goals and advance care directives to ensure medication decisions are person-centred. Lastly, decisions made with the residents and their surrogate decision maker are actioned, and the resident’s response to medications is monitored by all LTCF staff and health care professionals.

Figure 1. Shared decision making (SDM) in medication management for residents in long-term care facilities.

Strengths and Limitations

This present study demonstrated using qualitative methods, the residents’ beliefs, and motivation and external factors that facilitate or impede their involvement. The study conducted a considerable number of interviews with residents across a purposeful selection of LTCF. A limitation is that the median duration of interviews was 23 minutes and could not have resulted in an in-depth exploration on the topic. Nevertheless, the interviewer sought to conduct the interviews with residents without placing a burden on the participant. Another limitation is that the study did not specifically ask if residents had any inappropriate medications prescribed or medical conditions as the aim was to capture residents’ views on medication management in general. Therefore, further research is needed to explore residents’ views on shared decision making on potentially inappropriate medications. While the results may not be transferable to other countries, as the data were collected in six LTCF from metropolitan locations in Sydney, other studies indicate that the issues with SDM with older adults are not unique to Australia (Joseph-Williams et al., Reference Joseph-Williams, Elwyn and Edwards2014).

Conclusion

This study highlights that residents’ beliefs in control over decisions and concerns about medication are a significant function of the SDM process. It is important to identify residents’ beliefs and values regarding SDM prior to discussing options for medications. Not all residents want to participate in SDM and some are content to defer the decision to others. However, residents need to be given the choice to participate in SDM, at a level which they feel comfortable, and have that choice respected. For residents who do not have the capacity to make informed decisions, LTCFs need to defer to the designated surrogate decision-maker. Opportunities to improve resident participation in SDM include eliciting residents’ beliefs and values regarding participating in SDM, and a LTCF culture that respects residents’ right to take part in SDM, promotes open communication between residents and health care professionals and is attentive to residents’ goals and concerns.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge all those who participated in this study.

Description of authors’ roles

Sawan: conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting, revising the paper critically for important intellectual content. Jeon and Chen: conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, revising the paper critically for important intellectual content. Hilmer: analysis and interpretation of data, drafting, revising the paper critically for important intellectual content.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610222000205