No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

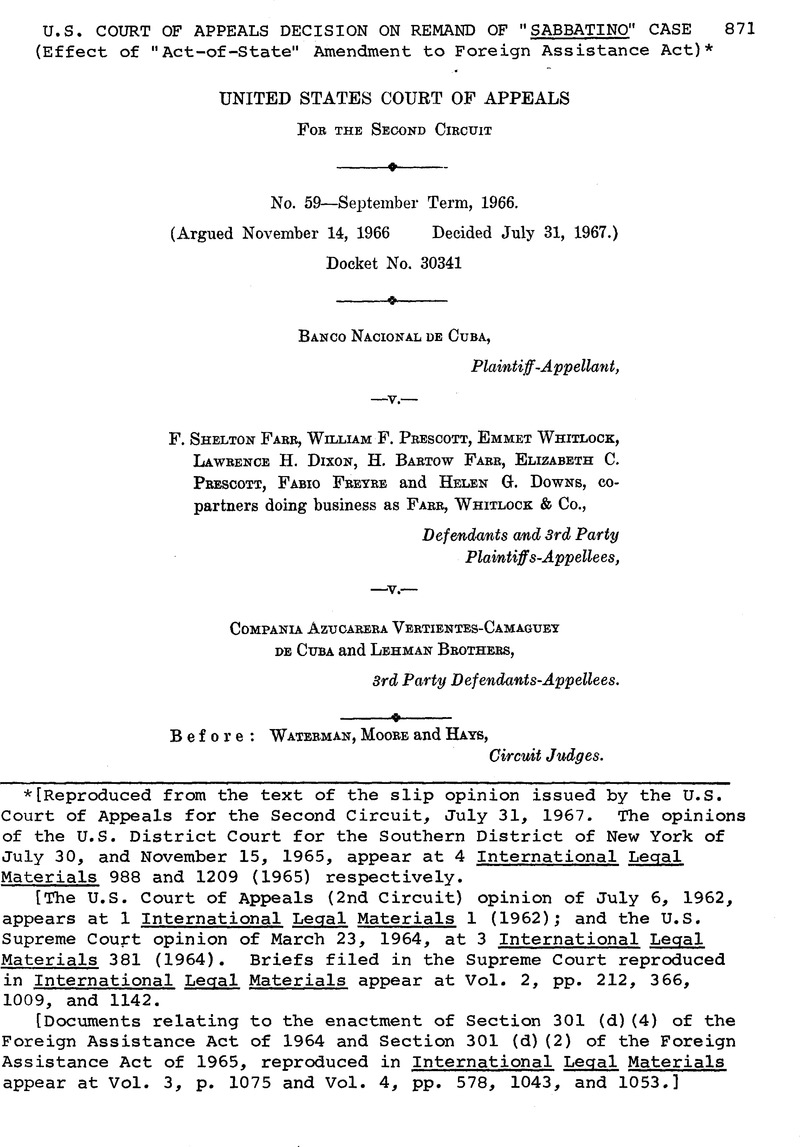

[Reproduced from the text of the slip opinion issued by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, July 31, 1967. The opinions of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York of July 30, and November 15, 1965, appear at 4 International Legal Materials 988 and 1209 (1965) respectively.

[The U.S. Court of Appeals (2nd Circuit) opinion of July 6, 1962, appears at 1 International Legal Materials 1 (1962); and the U.S. Supreme Court opinion of March 23, 1964, at 3 International Legal Materials 381 (1964). Briefs filed in the Supreme Court reproduced in International Legal Materials appear at Vol. 2, pp. 212, 3 66, 1009, and 1142.

[Documents relating to the enactment of Section 301 (d)(4) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1964 and Section 301 (d)(2) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1965, reproduced in International Legal Materials appear at Vol. 3, p. 1075 and Vol. 4, pp. 578, 1043, and 1053.]

* [Correction to the slip opinion made by the Clerk of the Court.]

1 It is stated in the district court’s opinion that thirty-five cases “involving a wide spectrum of questions arising out of Cuban expropriations” remain before the court below awaiting the final determination of this case. 243 F. Supp. 957, 962 (1965).

2 The resolution, which was promulgated by the Cuban President and Prime Minister provides:

WHEREAS, the attitude assumed by the Government and the Legislative Power of the United States of North America, of continued aggression, for political purposes, against the basic interests of the Cuban economy, as evidenced by the amendment to the Sugar Act adopted by the Congress of said country, whereby exceptional powers were conferred upon the President of said nation to reduce the participation of Cuban sugars in the sugar market of said country, as a weapon of political action against Cuba, was considered as the fundamental justification of said law.

WHEEEAS, the Chief Executive of the Government of the United States of North America, making use of said exceptional powers, and assuming an obvious attitude of economic and political aggression against our country, has reduced the participation of Cuban sugars in the North American market with the unquestionable design to attack Cuba and its revolutionary process.

WHEREAS, this action constitutes a reiteration of the continued conduct of the government of the United States of North America, intended to prevent the exercise of its sovereignty and its integral development by our people thereby serving the base interests of the North American trusts, which have hindered the growth of our economy and the consolidation of our political freedom.

* * * * *

WHEREAS, it is the duty of the peoples of Latin America to strive for the recovery of their native wealth by wrestling it from the hands of the foreign monopolies and interests which prevent their development, promote political interference, and impair the sovereignty of the underdeveloped countries of America.

* * * * *

Now, THEREFORE: In pursuance of the powers vested in us, in accordance with the provisions of Law No. 851, of July 6, 1960, we hereby

BESOLVE:

FIRST. TO order the nationalization, through compulsory expropriation, and, therefore, the adjudication in fee simple to the Cuban State, of all the property and enterprises located in the national territory, and the rights and interests resulting from the exploitation of such property and enterprises, owned by the juridical persons who are nationals of the United States of North America, or operators of enterprises in which nationals of said country have a predominating interest, as listed below, to wit:

* * * * *

22. Compania Azucarera Vertientes Camaguey de Cuba.

3 Farr, Whitlock received notice on August 23, 1960 that Peter L. F. Sabbatino on August 16 had bean appointed Temporary Receiver for the assets of C. A. V. within New York State pursuant to N. Y. Civ. Prac. Act, §977-b.

On August 26th Farr, Whitlock was notified by officers of C. A. V. that C. A. V., not the Cuban government, was the rightful owner of the sugar covered by the bills of lading which Societe Generale held. Farr, Whitlock and C. A. V. entered into an agreement on that day that Farr, Whitlock would retain the proceeds of the sugar shipments unless compelled to turn them over by court order. In return for this, C. A. V. would indemnify Farr, Whitlock against any claims and defend any suits against Farr, Whitlock for the sugar or the proceeds therefrom. In addition, C. A. V. promised to pay Farr, Whitlock ten per cent of the proceeds if C. A. V. were ultimately successful in obtaining them.

4 Our view that the two letters written by State Department officers indicated that the Executive Branch had no objection to a judicial determination as to the validity of Cuba’s actions under international law proved erroneous when the Executive Branch formally filed an amicus brief in the Supreme Court on the side of Banco Nacional and participated in the oral argument before the Court.

5 The Hickenlooper Amendment, which has also been referred to elsewhere as the Sabbatino Amendment or the Rule of Law Amendment, was attached to the Foreign Assistance Act of 1964 and became Section 301(d)(4) of that act. (Pub. L. 88-633, 78 Stat. 1009, 1013.)

The Amendment was reenacted in 1965 when the next Congress adopted the Foreign Assistance Act of 1965 (Pub. L. 89-171, 79 Stat. 653) which became law on September 6, 1965. The reenactment contained a slightly different version of the Hickenlooper Amendment, and is found in Section 301(d)(2) of that Public Law. Incorporated into the U. S. Code it is found at 22 U. S. C. {2370(e)(2). The only change was the substitution of “other right to property” for “other right” in two instances, and the deletion of Proviso 3, which had formerly made the Amendment inapplicable to any case in which the proceedings had not been commenced before January 1, 1966.

These changes in no way affect the case before us, and when we have discussed the Amendment throughout our opinion we have made no attempt to differentiate the Amendment in effect from October 7, 1964 from the Amendment in effect from September 6, 1965 to date. The Amendment, as first adopted, appears here in the text, the reenacted version is incorporated into footnote 20. It is interesting to note that these language changes became law during the 60 day period when the court below was awaiting word from the Executive before ordering the entry of judgment. See footnote 1 in Judge Bryan’s as yet unreported supplemental opinion.

6 C. A. V. moved before the Supreme Court to be substituted as a party for Sabbatino but the motion was denied without prejudice to its renewal in the lower courts. 376 U. S. at 407-08. C. A. V. submitted a brief and made oral argument before the Supreme Court as amicus curiae.

7 The court received a letter from the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York dated September 29, 1965 which reads:

In its decision of July 30, 1965 this Court afforded the Executive Branch the opportunity to file a suggestion indicating whether the application of the act of state doctrine is required by the foreign policy interests of the United States, as provided for in Section 620 (e) (2) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended (22 U. S. C. 2370(e)(2). I am instructed to inform the Court that no determination has been made that application of the act of state doctrine is required in this case by the foreign policy interests of the “United States.

So that there will be no ambiguity, the Court is advised that no such determination is contemplated.

8 Appellant claims that January 1, 1959, the date on which the Castro government took office in Cuba is “more symbolic than significant.”

Even if this is true we cannot see how it makes any difference in the face of the express inclusion of that date in the statute. Nor is the fact that the first expropriations after that date occurred in Brazil, not Cuba, of any relevance.

9 S. Rep. No. 1188, Part I, 88th Cong., 2d Sess. 24 (1964).

10 H. R. Rep. No. 1925, 88th Cong., 2d Sess. 16 (1964).

11 S. Rep No. 170, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. 19 (1965).

12 S. Rep. No. 170 was filed on April 28, 1965; the opinion below was not filed until July 30, 1965.

13 In view of our conclusion as to the applicability of the mandate rule, we need not decide whether the terms of the mandate in this case would allow the court below to consider the applicability of the Hickenlooper Amendment. See 243 F. Supp. at 971.

14 We do not find it necessary to consider whether it is too late for the Supreme Court tp amend its mandate. See 243 F. Supp. at 971, n. 7.

15 We note with interest the district court’s statement that there is “serious doubt” whether appellant, an instrumentality of a foreign government, should be considered a “person” within the meaning of the Fifth Amendment, 243 F. Supp. at 977. But cf. Russian Volunteer Fleet v. United States, 282 U. S. 481 (1931). However, we do not find it necessary to determine this issue because we think it clear that application of the Hickenlooper Amendment to this case does not violate the due process clause.

16 The Government urged the application of the act of state doctrine before the Supreme Court. On remand before the court below it took the position that the Hickenlooper Amendment was valid and constitutional but did not apply to any pending cases.

17 Compare Tennessee Power Co. v. TVA, 306 V. S. 118 (1939), and Alabama Power Co. v. Ickes, 302 U. S. 464 (1938), with Scripps-Howard Radio, Inc. v. FCC, 316 U. S. 4 (1942), and FCC v. Sanders Badio Station, 309 U. S. 470 (1940); Willing v. Chicago Auditorium Ass’n, 277 U. S. 274 (1928), with Aetna Life Ins. Co. v. Baworth, 300 U. S. 227 (1937); Thompson v. Magnolia Petroleum Co., 309 U. S. 478 (1940), and Byers v. McAuley, 149 U. S. 608 (1893), with Markham v. Allen, 326 U. S. 490 (1946); City of Atlanta v. Iekes, 308 V. S. 517 (1939) (per curiam), with Associated Indus, v. Iekes, 134 F. 2d 694 (2 Cir.), vacated per curiam as moot, 320 U. S. 707 (1943). All are cited at 243 F. Supp. at 975-76.

18 Inasmuch as we hold that the question presented here is justiciable, we do not reach the issue suggested by appellant that our approval of the congressional direction to the courts here requires us to consider whether there might be a constitutional compulsion that the courts accept the direction of Congress even as to issues the Court has held to be nonjusticiable because they are “political questions.”

19 We recognize the practical problem which faced the President here. He was presented with an extensive foreign aid bill the great majority of which was undoubtedly acceptable to him, but the bill contained as a “rider” the Hickenlooper Amendment, a provision which he might have wished to veto. However, the lack of an “item veto” is well established as part of our constitutional scheme and, in any case, we cannot presume that because he indicated opposition to it before it was passed by Congress, the President would have vetoed the Amendment even if it had been presented alone.

20 §2370(e)(1) provides:

§2370. Prohibitions against furnishing assistance.

(e)Nationalization, expropriation or seizure of property of United States citizens, or taxation or other exaction having same effect; failure to compensate or to provide relief from taxes, exactions, or conditions; report on full value of property by Foreign Claims Settlement Commission; act of state doctrine.

(1) The President shall suspend assistance to the government of any country to which assistance is provided under this chapter or any other Act when the government of such country or any government agency or subdivision within such country on or after January 1, 1962—

(A)has nationalized or expropriated or seized ownership or control of property owned by any United States citizen or by any corporation, partnership, or association not less than 50 per centum beneficially owned by United States citizens, or

(B)has taken steps to repudiate or nullify existing contracts or agreements with any United States citizen or any corporation, partnership, or association not less than 50 per centum beneficially owned by United States citizens, or

(C)has imposed or enforced discriminatory taxes or other exactions, or restrictive maintenance or operational conditions, or has taken other actions, which have the effect of nationalizing, expropriating, or otherwise seizing ownership or control of property so owned,

and such country, government agency, or government subdivision fails within a reasonable time (not more than six months after such action, or, in the event of a referral to the Foreign Claims Settlement Commission of the United States within such period as provided herein, not more than twenty days after the report of the Commission is received) to take appropriate steps, which may include arbitration, to discharge its obligations under international law toward such citizen or entity, including speedy compensation for such property in convertible foreign exchange, equivalent to the full value thereof, as required by international law, or fails to take steps designed to provide relief from such taxes, exactions, or conditions, as the case may be; and such suspension shall continue until the President is satisfied that appropriate steps are being taken, and no other provision of this chapter shall be construed to authorize the President to waive the provisions of this subsection.

Upon request of the President (within seventy days after such action referred to in subparagraphs (A), (B), or (C) of this paragraph), the Foreign Claims Settlement Commission of the United States (established pursuant to Reorganization Plan No. 1 of 1954, 68 Stat. 1279) is hereby authorized to evaluate expropriated property, determining the full value of any property nationalized, expropriated, or seized, or subjected to discriminatory or other actions as aforesaid, for purposes of this subsection and to render an advisory report to the President within ninety days after such request. Unless authorized by the President, the Commission shall not publish its advisory report except to the citizen or entity owning such property. There is hereby authorized to be appropriated such amount, to remain available until expended, as may be necessary from time to time to enable the Commission to carry out expeditiously its functions under this subsection.

This subsection is followed by Section 2370(e)(2), the Hickenlooper Amendment in, permanent form, substantially as it appears on page 3189, supra, but now with the phrase “to property” twice inserted, and with proviso 3 omitted.

(2)Notwithstanding any other provision of law, no court in the United States shall decline on the ground of the federal act of state doctrine to make a determination on the merits giving effect to the principles of international law in a case in which a claim of title or other right to property is asserted by any party including a foreign state (or a party claiming through such state) based upon (or traced through) a confiscation or other taking after January 1, 1959, by an act of that state in violation of the principles of international law, including the principles of compensation and the other standards set out in this subsection: Provided, That this subparagraph shall not be applicable (1) in any case in which an act of a foreign state is not contrary to international law or with respect to a claim of title or other right to property acquired pursuant to an irrevocable letter of credit of not more than 180 days duration issued in good faith prior to the time of the confiscation or other taking, or (2) in any case with respect to which the President determines that application of .the act of state doctrine is required in that particular case by the foreign policy interests of the United States and a suggestion to this effect is filed on his behalf in that case with the court.

* [Correction to the slip opinion made by the Clerk of the Court.]