No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

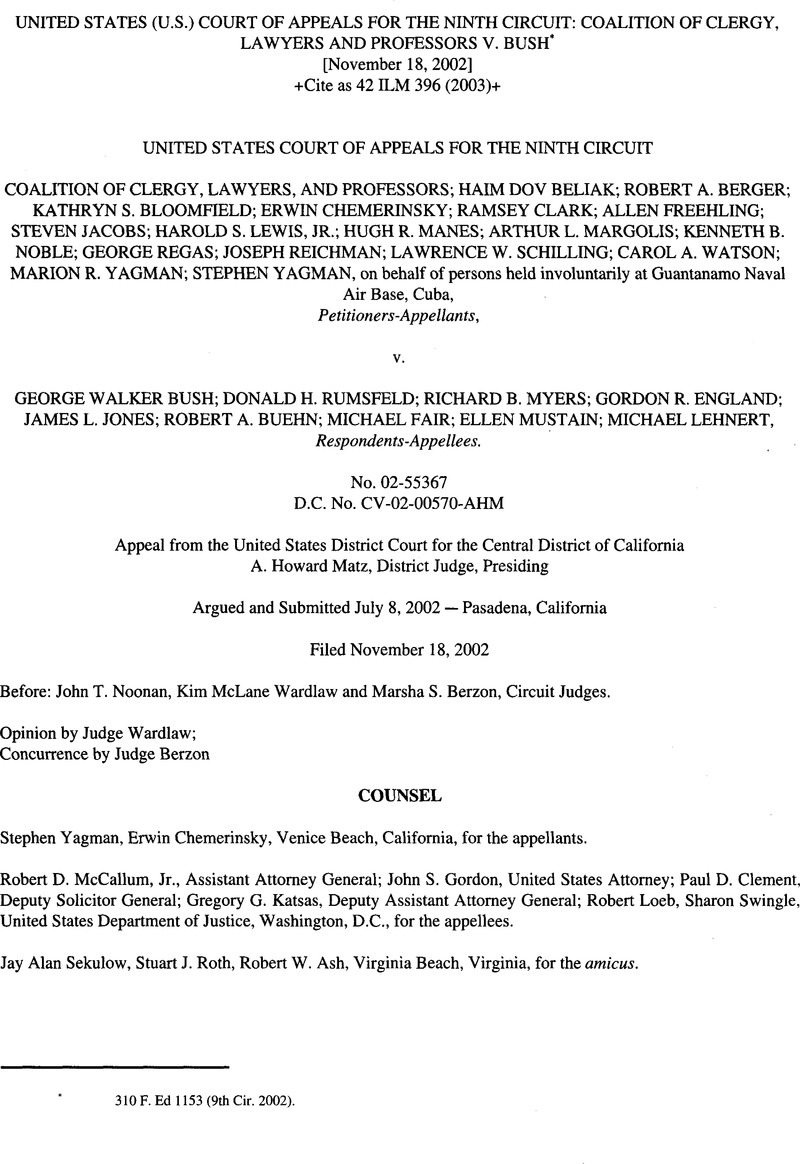

* 310F.Ed 1153 (9thCir. 2002).

1 The members of the Coalition include: Rabbi Haim Dov Beliak, Prof. Robert A. Berger, Kathryn S. Bloomfield, Esq., Prof. Erwin Chemerinsky, Ramsey Clark, Esq., Rabbi Allen Freehling, Rabbi Steven Jacobs, Prof. Harold S. Lewis, Jr., Hugh R. Manes, Esq., Arthur L. Margolis, Esq., Prof. Kenneth B. Noble, Rev. George Regas, Joseph Reichman, Esq., Lawrence W. Schilling, Esq., Carol A. Watson, Esq., Marion R. Yagman, Esq., and Stephen Yagman, Esq.

2 The Coalition requested at oral argument that we remand for an evidentiary hearing on a variety of issues, including the detainees' lack of access to lawyers or courts. We deny this request because the Coalition has not even made a preliminary showing that upon remand it could prove, in light of the record that is before the court, that any individual detainee is being held totally incommunicado. A bald assertion that the detainees are held incommunicado when the record makes clear the contrary, does not necessitate a hearing; indeed it appears such a hearing would be futile.

3 Even if the Coalition were correct, we are constrained to adhere to our circuit's prior precedent, and the appropriate mechanism to revisit this framework would be through the en bane process. United States v. Ramirez-Cortez 213 F.3d 1149,1156 (9th Cir. 2000). However, as explained below, Massie's restatement of the Whitmore standard is not merely a gloss, but flows directly from the Court's rationale.

4 There is no question that the holding in Johnson represents a formidable obstacle to the rights of the detainees at Camp X-Ray to the writ of habeas corpus; it is impossible to ignore, as the case well matches the extraordinary circumstances here. After Germany had surrendered in World War II, German spies were captured by allied forces in China. They were tried and convicted by a military tribunal, imprisoned in Germany and sought a writ of habeas corpus in the United States federal courts. Johnson 339 U.S. at 766. The German spies were thus enemy aliens who were captured and tried abroad, and imprisoned there by the United States military. The Supreme Court held that the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus could not be extended to aliens held outside the sovereign territory of the United States. Id. at 778; see also Zadvydas v. Davis 533 U.S. 678, 693 (2001) (“It is well established that certain constitutional protections available to persons inside the United States are unavailable to aliens outside of our geographic borders.“)

1 The related context of third-party standing recognizes a wide range of relationships in which the third-parties’ interests are sufficiently aligned with the interests of the rights-holder that standing is appropriate. See, e.g., U.S. Dept. of Labor v. Tripplett 494 U.S. 715, 720-21 (1990) (lawyer-client); Carey v. Population Serv. Ml 431 U.S. 678, 682 (1978) (vendor-customer); Singleton v. Wulff 428 U.S. 106 (1976) (doctor-patient); Pierce v. Society of Sisters 268 U.S. 510, 536 (school-students). In the proper context these are the sorts of relationships that could support next friend standing. I would not limit the pertinent relationships to agency or consent relationships.

2 At best, Coalition could assert the relationship of a potential lawyer to a potential client. In some circumstances, such a relationship might create third party standing. See note 3, infra. I cannot conclude on the particular facts of this case, however, that next friend standing on this basis is appropriate, especially in light of the Coalition's failure to try to contact the detainees. Accord Sanchez- Velasco 287 F.3d at 1026-27.

3 I note that in some instances plaintiffs such as those here may be able to establish standing on their own behalf. It is plausible, for example, that the inability of the lawyer-plaintiffs to represent as clients the Guantanamo detainees when they wished to do so (whether for a fee or otherwise) created an injury-in-fact sufficient under Article III for standing purposes. Cf. Dept of Labor v. Triplett 494 U.S. 715,720-21 (1990) (lawyer injured by fee-limitation statute had standing to assert the “due process right to obtain legal representation” of his clients). Coalition does not allege such an injury. Although Judges Garland and Williams have not joined Judge Randolph's concurring opinion, they do not intend thereby to express any view about its reasoning. They believe the issues addressed need not be reached.