No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

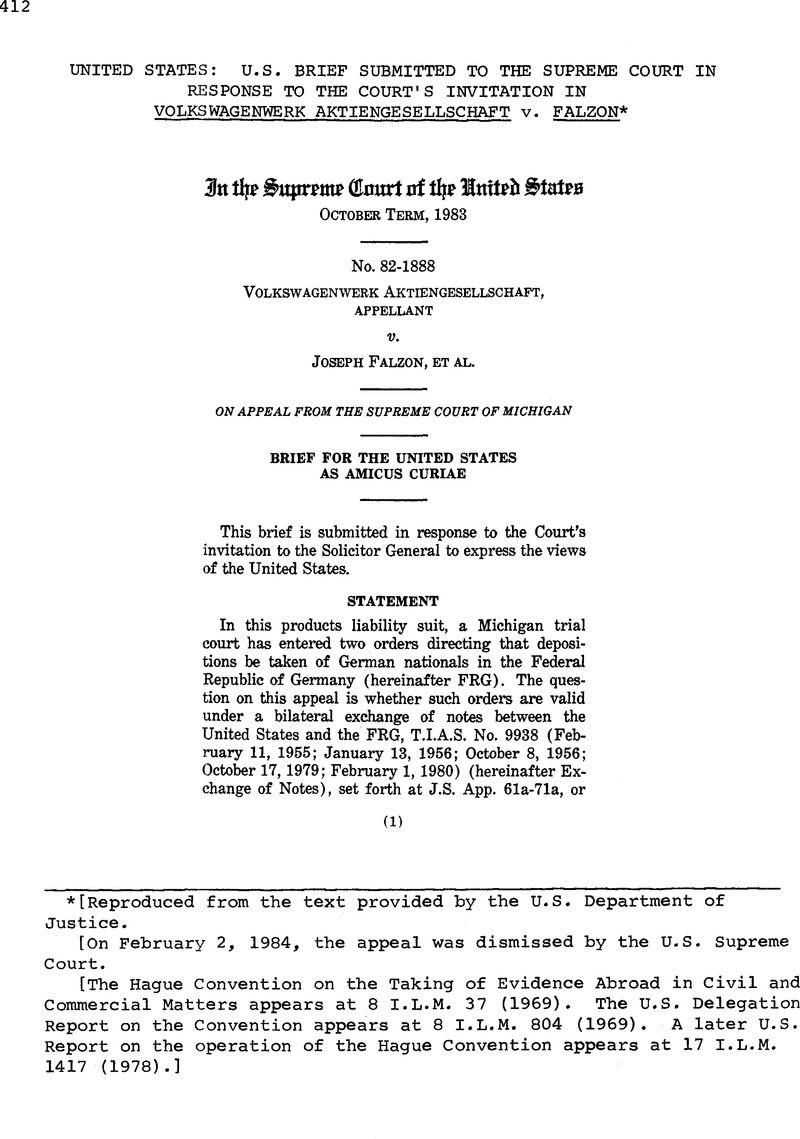

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Department of Justice.

[On February 2, 1984, the appeal was dismissed by the U.S. Supreme Court.

[The Hague Convention on the Taking of Evidence Abroad in Civil and Commercial Matters appears at 8 I.L.M. 37 (1969). The U.S. Delegation Report on the Convention appears at 8 I.L.M. 804 (1969). A later U.S. Report on the operation of the Hague Convention appears at 17 I.L.M. 1417 (1978).]

1 We note that this Court appears to lack jurisdiction over this case except by way of certiorari under 28 U.S.C. 1257(3), as requested in the alternative by appellant pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 2103 (see J.S. 18). Appellate jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. 1257(1) clearly is not appropriate here, because the state courts have issued no decision in this case against the validity of a treaty. Similarly, jurisdiction by way of appeal under 28 U.S.C. 1257 (2) also is unavailable. The record, as reflected in the papers filed in this Court, does not reveal that appellant explicitly challenged the validity of the Michigan Court Rules as applied, but rather shows that appellant attacked the particular actions of the trial court as invalid on federal grounds. There is therefore no jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. 1257(2). See Richmond Newspapers, Inc. V. Virginia, 448 U.S. 555, 562-563 n.4 (1980) (plurality opinion); Hanson v. Denckla, 357 U.S. 235, 244 & n.4 (1958); Charleston Federal Savings & Loan Ass'n v. Alderson, 324 U.S. 182, 185-187 (1945). This case, like virtually every case, involves court actions taken pursuant to court rules. No distinctions in the court rules themselves are challenged, as in Mayer v. City of Chicago, 404 U.S. 189 (1971), and In re Griffiths, 413 U.S. 717, 718 (1973), and no assertedly unconstitutional application of a substantive state statute is involved, as in Japan Line, Ltd. v. County of Los Angeles, 441 U.S. 434, 440-441 (1979), and Cohen V. California, 403 U.S. 15, 17-18 (1971)

2 Evidence may also be taken from German nationals by private commissioners, but only on express prior approval of the relevant FRG Central Authority (Art. 17; FRG Instrument of Ratification, U B(4), set forth at J.S. App. 52a). See Shemanski, supra, 17 Int'l Law. at 479.

3 The fact that a state court has personal jurisdiction over a private party (see Motion to Dismiss or Affirm 23) does not mean that treaty limits on proceedings for the taking of evidence abroad somehow do not apply to discovery orders addressed to such parties. The Evidence Convention protects the judicial sovereignty of the country in which evidence is taken, not the interests of the parties to the suit. Accordingly, its strictures apply regardless of the existence of personal jurisdiction.

4 The occupying powers gathered evidence freely from German and third-country nationals in connection with such matters as war crimes investigations, restitution cases, the location of missing persons, and other similar endeavors related to the war.

5 The orders in the instant case and in other cases (e.g., Volkswagenwerk, A.G. v. Superior Court, supra) have resulted in strong written and oral diplomatic protests from the FRG. In May 1983, representatives of the FRG and the United States Department of State informally agreed that the FRG would continue to permit United States consular officers to take voluntary testimony from non-United States nationals in Germany for a limited time, pending further formal clarification of the Exchange of Notes. It was also agreed that the United States would notify the German Federal Ministry of Justice in advance of all intended evidence taking, so that the FRG would have the opportunity to exercise its right of veto in a given case.

6 Since the FRG's protests are specifically directed at the Michigan trial court's orders, which the FRG considers inherently compulsory, we cannot predict whether the FRG would object to the voluntary testimony of appellant's employees in the FRG in the absence of such orders. Furthermore, of course, the Evidence Convention machinery remains available to appellees.

7 If the appeal is not otherwise dismissed for lack of jurisdiction (see note 1, supra), it should be dismissed on the ground that it does not present a substantial federal question at this stage of the litigation. For the same reason, the alternative petition for a writ of certiorari should be denied.

* This letter is reproduced at J.S. App. 72a-74a.