No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

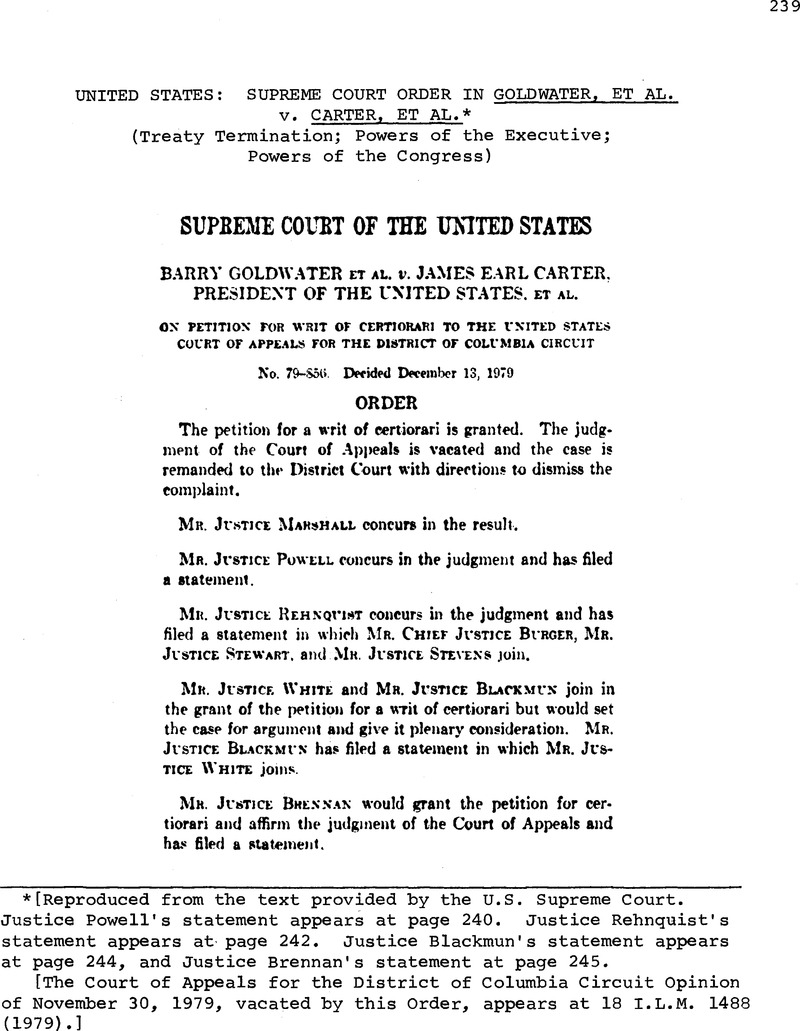

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Supreme Court. Justice Powell's statement appears at page 240. Justice Rehnquist's statement appears at page 242. Justice Blackmun's statement appears at page 244, and Justice Brennan's statement at page 245.

[The Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit Opinion of November 30, 1979, vacated by this Order, appears at 18 I.L.M. 1488 (1979).]

1 The Court has recognized that, in the area of foreign policy, Congress may leave the President with wide discretion that otherwise might run afoul of ihe nondelegation doctrine. United States v. Curtiss-W right Export Corp.. 299 V. S. 304 (193fi). As stated in tkat case, “the President alone has the power to speak or listen as a representative of the Nation. He main treatie with the advice and consent of the Senate; but he alone negotiate?.” Id., at 319 (emphasis in the original). Resolution of this case would interfere with neither the President's ability to negotiate treaties nor his duty to execute their provisions. We are merely being asked to decide whether a treaty, which cannot be ratified without Senate approval, continues in effect until the Senate or jicrhaps the Congress take further action.

2 Coleman v. Milter. 307 V. S. 433 (1939). is not relevant here. In that case, the Court was asked to review the legitimacy of a State's ratification of a constitutional amendment. Four Members of the Court stated that Congress has exclusive power over the ratification process Id at 456-460 (Black, J. concurring, with whom Roberts, Frankfurter, and Douglas, J.I., joined). Three Members of the Court concluded more narrowly that the Court could not pass upon the efficacy of state ratification. They also found no standards by which the Court could fix a reasonable time for the ratification of a proposed amendment. Id., at 452-454.

The proposed constitutional amendment at issue in Coleman would have overruled decisions of this Court. Compare id., at 435. n. 1 with Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Co.. 259 V. S. 20 (1922): Hammer v. Dageuhart. 257 U. S. 251 (1918). Thus, judicial'review of the legitimacy of a State's ratification would have compelled this Court to oversee the very constitutional process used to reverse Supreme Court decisions. In such circumstances it may be entirely appropriate for the Judicial Branch of government to step aside. See Seharpf. .Judicial Renew and Tin Political Question: A Functional Analysis, 75 Yale L. .1. 517. 589 (1966) The present case involves no similar principle of judicial nonintervention.

1 As observed by Judge Wright in his concurring opinion below:

“Congress has initiated the termination of treaties by directing or requiring the President to give notice of termination, without any prior presidential request. Congress has annulled treaties without any presidential notice. It luv conferred on the President the power to terminate a particular treaty, and it has enacted statutes practically nullifying the domestic effects of a treaty and thus caused the President to carry out termination. . . . [r] Moreover, Congress has a variety of powerful tools for influencing foreign policy decision- that bear on treaty matters. Under Article 1. Section S of the Constitution, it can regulate commerce with foreign nations, raise and supjort aniiirs, and declare war. It has power over the appointment of ambassador? and the funding of embassies and consulate?. Congress thus retains a strong influence over the President's conduct in treaty matters. [*] As pur political history demonstrates, treaty creation and termination are complex phenomena rooted in the dynamic relationship between the two political branches of our government. We thus should decline the invitation to set in concrete a particular constitutionally acceptable arrangement by which the President and Congress are to share treaty termination.” Petition, pp. 44A-45A (footnotes omitted).

2 This Court, of course, may not prohibit state courts from deciding political questions, any more than it may prohibit them from deciding quest ion? that are moot, Doremus v. Board of Education. 342 U S. 429, 434 (1952). so long as they do not trench upon exclusively federal questions of foreign policy. Znchtntig v. MilUr, 389 lT. S. 429, 441 (196S).