Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

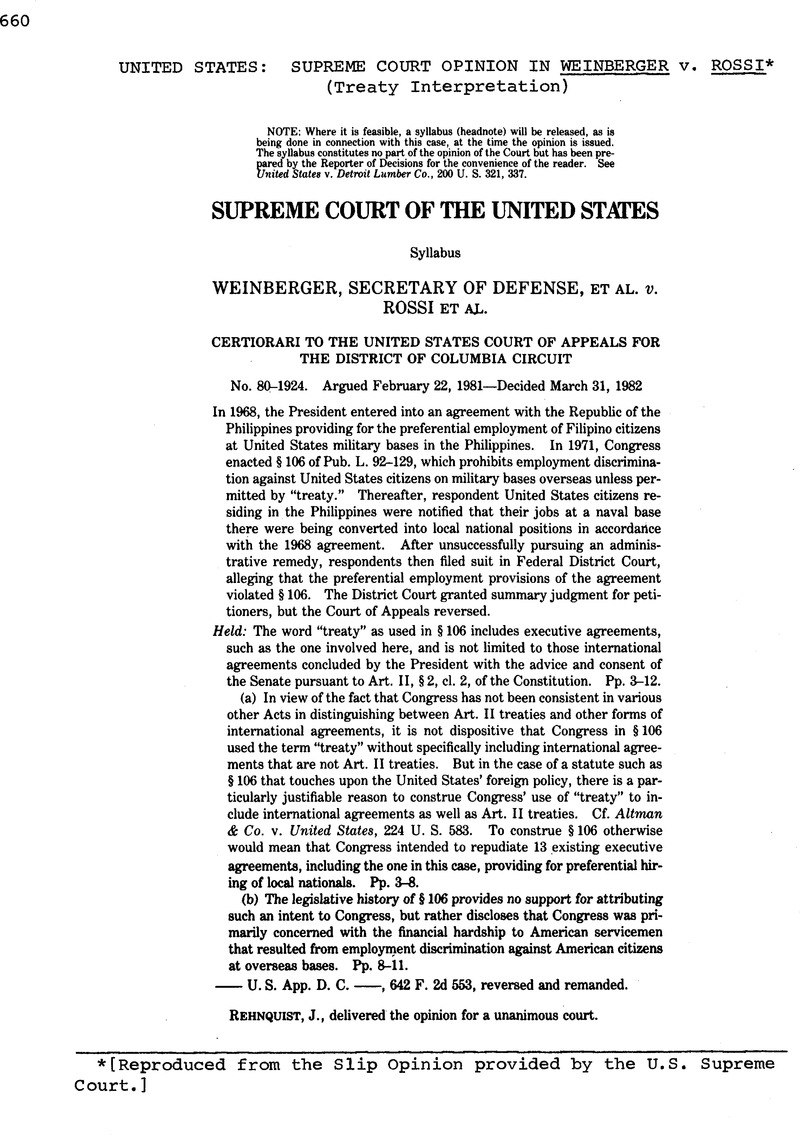

[Reproduced from the Slip Opinion provided by the U.S. Supreme Court.]

1 This agreement has been amended periodically, most recently on January 7, 1979. 30 U. S. T. 863, T.I.A.S. No. 9224.

2 In relevant part, Article I of the BLA provides:

“1. Preferential Employment.—The United States Armed Forces in the Philippines shall fill the needs for civilian employment by employing Filipino citizens, except when the needed skills are found, in consultation with the Philippine Department of Labor, not to be locally available, or when otherwise necessary for reasons of security of special management needs, in which cases United States nationals may be employed. . . .”

3 Section 106 provides in pertinent part:

“Unless prohibited by treaty, no person shall be discriminated against by the Department of Defense or by any officer or employee thereof, in the employment of civilian personnel at any facility or installation operated by the Department of Defense in any foreign country because such person is a citizen of the United States or is a dependent of a member of the Armed Forces of the United States.” 5 U. S. C. § 7201 note (1976 ed., Supp. Ill) (emphasis added).

4 Brief for Petitioner 5-6 and nn. 3-4.

5 See Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, May 23, 1969, Art. 2, 11(a), reprinted in 63 Am. J. Int'l L. 875, 876 (1969); Restatement of the Foreign Relations of the United States, Introductory note 3, at 74 (Tent. Draft No. 1 April 1980) (“[I]nternational law does not distinguish between agreements designated as 'treaties' and other agreements”).

6 We have recognized, however, that the President may enter into certain binding agreements with foreign nations without complying with the formalities required by the Treaty Clause of the Constitution, even when the agreement compromises commercial claims between United States citizens and a foreign power. See, e. g., Dames & Moore v. Regan—U. S.—(1981); United States v. Pink, 315 U. S. 203 (1942); United States v. Belmont, 301 U. S. 324 (1937). Even though such agreements are not treaties under the Treaty Clause of the Constitution, they may in appropriate circumstances have an effect similar to treaties in some areas of domestic law.

7 In this context, it is entirely logical that Congress should distinguish between Article II treaties and other international agreements. Submission of Article II treaties to the Senate for ratification is already required by the Constitution.

8 Congress defined “treaty” to mean "any international fishery agreement which is a treaty within the meaning of section 2 of article II of the Constitution. 16 U. S. C. § 1802(23).

9 “[N]o action shall be taken under this chapter or any other law that will obligate the United States to disarm or to reduce or to limit the Armed Forces or armaments of the United States, except pursuant to the treaty making power of the President under the Constitution or unless authorized by further affirmative legislation by the Congress of the United States.” 22 U. S. C. §2573.

10 See 117 Cong. Rec. 14395 (1971) (remarks of Sen. Schweiker).

11 “I have never heard of anything so ridiculous in my life. We actually send our GFs to Europe at poverty wages. We do not pay to send the wives there. They have to beg or borrow that money. They get over there, and if they do bring their wives at their own expense, the wives cannot even go to the Army Exchange Service and get ajob, because a general has sent out a memorandum that says we are going to give those jobs to the nationals of the countries involved.” 117 Cong. Rec. 14395 (1971).

At another point, Sen. Schweiker commented: “Here is an American general saying that when the GPs go to their canteen or service post exchange and spend their money, they do not even have the right to have their wives working there because we should give these jobs to German nationals.” Id., at 16128.

12 See, e. g., 117 Cong. Rec. 14395 (1971) (remarks of Sen. Schweiker); id., at 16126 (remarks of Sen. Cook); ibid, (remarks of Sen. Hughes).

13 Agreement Concerning the Status of United States Personnel and Property (Annex), May 8, 1951, United States-Iceland, 2 U. S. T. 1533, T.I.A.S. No. 4296.

14 This NATO agreement is an Article II treaty.

15 The contemporaneous remarks of a sponsor of legislation are certainly not controlling in analyzing legislative history. Consumer Product Safety Comm'n v. GTE Sylvania, 447 U. S. 102, 118 (1980); Chrysler Corp. v. Brown, 441 U. S. 281, 311 (1979)

16 See H.R. Rep. No. 95-68, 95th Cong., 1st Sess. 25 (1977); H.R. Rep. No. 97-410, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. 54 (1981).

17 Although we do not ascribe it much weight, we note that a Conference Committee recently deleted a provision that would have prohibited the hiring of foreign nationals at military bases overseas when qualified United States citizens are available. H.R. Rep. No. 97-410, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. 54 (1981). In urging this provision's deletion, Sen. Percy explained that the provision would place the United States in violation of its obligations inter alia under the BLA with the Philippines. 127 Cong. Rec. S14110 (daily ed. Nov. 30, 1981). He argued:

“Some host nations might view enactment of 777 as a material breach of our agreements, thus entitling them to open negotiations on terminating, redefining or further restricting U. S. basing and use rights. Nations could, for example, retaliate by suspending or reducing our current rights to engage in routine military operations such as aircraft transits.” Ibid.

18 In view of its construction of § 106, the Court of Appeals found it unnecessary to determine whether the BLA in the instant case violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U. S. C. § 2000e. Rossi v. Brown, 642 F. 2d, at 561 n. 36. Because this question was neither raised in the petition for certiorari nor reached by the Court of Appeals, we do not consider it.