No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

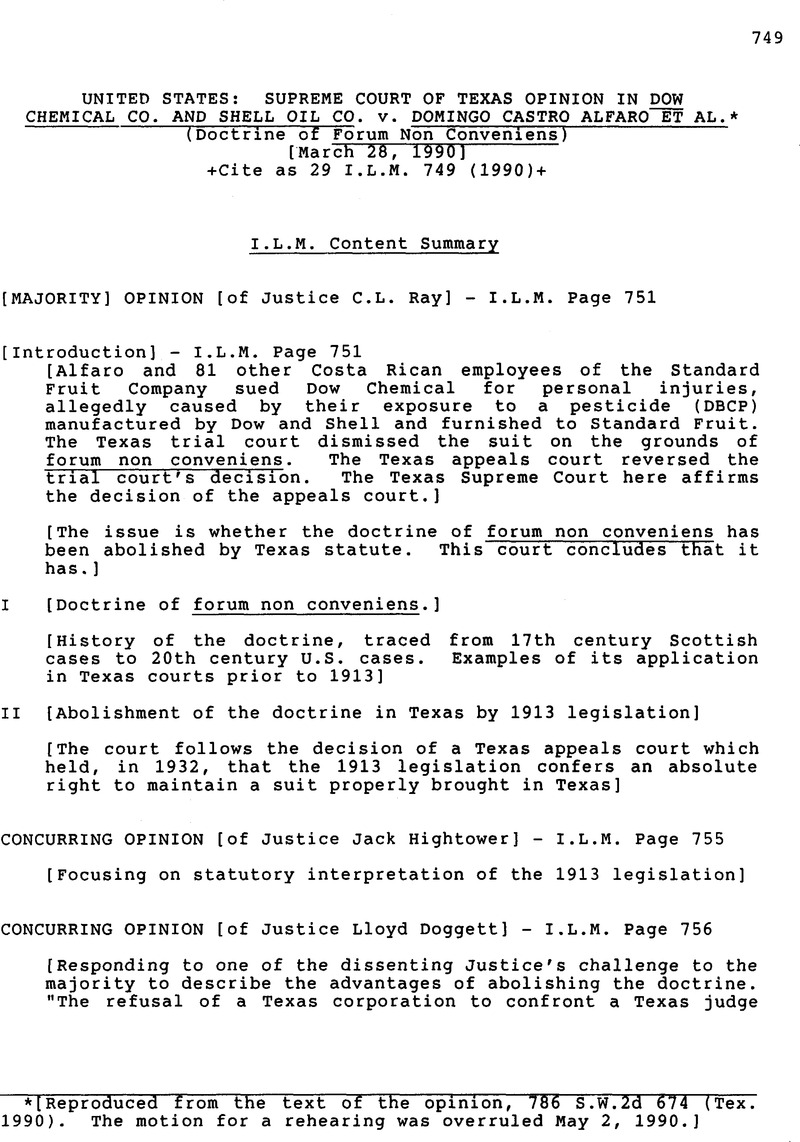

* [Reproduced from the text of the opinion, 786 S.W.2d 674 (Tex. 1990). The motion for a rehearing was overruled May 2, 1990.]

(*) Prospective members are listed under the above categories only for the purpose this Agreement. Recipient countries are referred to elsewhere in this Agreement as Central and Eastern European countries.

1 It is neither I nor the majority who find it necessary to have opinions or statutes “twisted.” Gonzalez dissent, 786 S.W.2d 692. Today's majority merely reconfirms the action of the legislature in abolishing the doctrine of forum non conveniens. I do agree with Justice Gonzalez that “sweeping implementations of social welfare policy” are sought here—not by my concurrence but in the unswerving determination of the dissenters to protect the welfare of multinational corporations.

2 Stewart, Forum Non Conveniens: A Doctrine in Search of a Role, 74 Cal.L.Rev. 1259. 1264 n. 18 (1986).

3 Justice Hecht argues that Allen is not controlling because it has not been subsequently followed.After citing the decisions of this courtin Couch v. Chevron Inti Co., 682 S.W.2d 534, 535 (Tex. 1984) and Flaiz v. Moore, 359 S.W.2d 872, 876 (Tcx.1962), he adopts a strange new reading of opinions, stating that “Couch and Flaiz unmistakably disapproved of Allen v. Bass without even bothering to cite it.” Hecht dis-sent, 786 S.W.2d 706. In Texas, we have not subscribed to the theory that opinions may be overruled without even informing anyone of such action. The doctrine of stare decisis is not usually discarded in such a cavalier manner through rejection of longstanding precedent by mere implication. Nothing said by the court in Couch is at all inconsistent with Allen. Rather, due to the appellate rules requiring preservation of error, this court never reached the issue of forum non conveniens in Couch. See Couch, 682 S.W.2d at 535. Justice Gonzalez disregards Allen principally by reliance upon Flail v. Moore, 359 S.W.2d 872 (Tex.1962).This court did not reach the issue of forum non conveniens in Flaiz: It should be pointed out that we have not considered or attempted to decide in this case: (1) the extent to which the forum non conveniens principle is recognized in Texas; (2) whether article 4678 is mandatory and deprives the court of any discretion 359 S.W.2d at 876.Neither Couch nor Flaiz casts doubt upon the holding in Allen. Justice Gonzalez next attempts to distinguish Allen by arguing that the only doctrine it involved was that of comity, not forum non conveniens. A review of Allen and the subsequently refused application for writ of error indicates that the issue of forum non conveniens was presented and rejected. Even more ironic is the fact that Justice Gonzalez includes comity as one of his forum non conveniens public interest factors. See Gonzalez dissent, 786 S.W.2d 690.

4 In an apparent attempt to gain access to favorable federal forum non conveniens rules and to avoid Texas procedural law. Shell and Dow removed this case to the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas despite the clear absence of any basis for federal jurisdiction.United States District Judge DeAnda,in remanding the case, labeled Shell and Dow's efforts to distinguish plainly controlling authority against remova“specious.” Over three years after the plaintiffs filed this lawsuit in Houston, Shell and Dow obtained a dismissal of the action on forum non conveniens grounds. Extensive discovery had already been completed, interrogatories had already been answered by the individual plaintiffs and the individual plaintiffs had already agreed to appear in Houston for medical examinations and depositions. Many of the so-called “conve-nience” problems had already been resolved in this litigation prior to the dismissal under forum non conveniens.United States District Judge DeAnda,in remanding the case, labeled Shell and Dow's efforts to distinguish plainly controlling authority against removal “specious.” Over three years after the plaintiffs filed this lawsuit in Houston, Shell and Dow obtained a dismissal of the action on forum non conveniens grounds. Extensive discovery had already been completed, interrogatories had already been answered by the individual plaintiffs and the individual plaintiffs had already agreed to appear in Houston for medical examinations and depositions. Many of the so-called “convenience” problems had already been resolved in this litigation prior to the dismissal under forum non conveniens. United States District Judge DeAnda,in remanding the case, labeled Shell and Dow's efforts to distinguish plainly controlling authority against removal “specious.” Over three years after the plaintiffs filed this lawsuit in Houston, Shell and Dow obtained a dismissal of the action on forum non conveniens grounds. Extensive discovery had already been completed, interrogatories had already been answered by the individual plaintiffs and the individual plaintiffs had already agreed to appear in Houston for medical examinations and depositions. Many of the so-called “conve-nience” problems had already been resolved in this litigation prior to the dismissal under forum non conveniens.

5 Professor David Robertson of the University of Texas School of Law attempted to discover the subsequent history of each reported transna-tional case dismissed under forum non conve-niens from Gulf Oil v. Gilbert, 330 VS. 501, 67 S.Ct. 839, 91 L.Ed. 1055 (1947) to the end of 1984. Data was received on 55 personal injury cases and 30 commercial cases. Of the 55 per-sonal injury cases, only one was actually tried in a foreign court. Only two of the 30 commercial cases reached trial. See Robertson, supra, at 419.

6 Such a result in the name of “convenience” would undoubtedly follow a dismissal under forum non conveniens in the case at bar. The plaintiffs, who earn approximately one dollar per hour working at the banana plantation, clearly cannot compete financially with Shell and Dow in carrying on the litigation. More importantly, the cost of just one trip to Houston to review the documents produced by Shell would exceed the estimated maximum possible recovery in Costa Rica.In an unchallenged affidavit, a senior Costa Rican labor judge stated that the maximum possible recovery in Costa Rica would approximate 100,000 colones, just over $1,080 at current exchange rates. Assuming such a recovery were possible, no lawyer, in Costa Rica or elsewhere, could afford to take such a case—against two giant corporations vigilantly defending themselves in litigation. Further, Costa Rica permits neither jury trials nor depositions of nonparty witnesses. Attempting to depose a Dow representative concerning the company's knowledge of DBCP hazards will prove to be an impossible task as Dow is not required to produce that person in Costa Rica. It is not unlikely that Shell and Dow seek a forum non conveniens dismissal not in pursuit of fairness and convenience, but rather as a shield against the litigation itself. If successful, Shell and Dow, like many American multina-tional corporations before them, would have secured a largely impenetrable shield against meaningful lawsuits for their alleged torts causing injury abroad.

7 It is interesting that Justice Hecht pronounces the doctrine as one founded in considerations of ‘fundamental fairness,” only to later reject the private factors—the doctrine's only focus on fairness to the parties.Nevertheless, he clings to the so-called doctrine of convenience, claiming that “[t]he public factors, however, deserve the same consideration now as when Gulf Oil was written.“ 786 S.W.2d 708.

8 Justice Cook seems to suggest that it may violate due process for Shell to be sued in Houston.It is an extremely novel holding, unprece- dented in American constitutional law, that a corporation could be denied due process by being sued in its hometown. Justice Cook argues in his dissent that “the due process test has not developed answers … to questions regarding considerations of fairness.“ He claims that forum non conveniens has “bridged the gap in the development of the due process test,” and concludes that “the majority shatters that bridge.“786 S.W.2d 702. Justice Cook is wrong on both counts. The due process test in personal jurisdiction cases, although admittedly complex, is developing fully and quickly. Since 1977, the Supreme Court has decided eleven major personal jurisdiction cases. See e.g., As- ahi Metal Indus. Co.w. Superior Court, 480 U.S. 102, 107 S.CL 1026, 94 LEd.2d 92 (1987); Phil-lips Petroleum Co. v. Shutts, All U.S. 797, 105 S.Ct. 2965, 86 L.Ed.2d 628 (1985); Burger King Corp. v. Rudzewicz, 471 U.S. 462, 105 S.Ct. 2174, 85 L.Ed.2d 528 (1985); Helicopteros Nacionales de Columbia, S.A. v. Hall, 466 U.S. 408, 104 S.Ct. 1868, 80 LEd.2d 404 (1984); Colder v. Jones, 465 U.S. 783, 104 S.Ct. 1482, 79 L.Ed.2d 804 (1984); Keeton v. Hustler Magazine, Inc., 465 VS. 770, 104 S.CL 1473, 79 L.Ed.2d 790 (1984); Insurance Corp. of Ireland v. Campagnie des Bauxites de Guinee, 456 U.S. 694, 102 S.Ct. 2099, 72 L.Ed.2d 492 (1982); Rush v. Savchuk, 444 U.S. 320, 100 S.Ct. 571, 62 LEd 516 (1980); World-Wide Volkswagen Corp. v. Woodson, AM VS. 286, 100 S.Ct. 559, 62 LED 2d 490 (1980); Kulko v. Superior Court, 436 U.S. 84, 98 S.Ct. 1690, 56 LEd Id 132 (1978); Shaffer v. Heitner, 433 US. 186, 97 S.CL 2569, 53 LEd.2d 683 (1977). Justice Cook confuses two distinct issues in suggesting that forum non conveniens should be used to “bridge the gap” in the development of the due process test. Forum non conveniens is never considered until and unless the personal jurisdictiondue process determination is complete. See Gulf Oil 330 U.S. at 504, 67 S.Ct. at 841. Justice Cook's backward reasoning illustrates a significant problem with relying on the doctrine of forum non conveniens, explained by one commentator as follows: Issues going to the existence of jurisdiction are conceptualised as turning on rules and principles which, however flexible and opentextured, lend an element of solidity that is wholly lacking for discretionary decisions to declineto exercise jurisdiction When judges have too much discretion-declining jurisdiction, they will inevitably not put in the hard work necessary to formulate and apply sensible jurisdictional rules.What has happened in American jurisprudence is a form of “buck passing” whereby the vague and amorphous “forum non conveniens doctrine has come to accomodate the collective shortcomings and excesses of modern rules governing jurisdiction, venue, and choice of law.” Robertson, supra, 103 L.Q.Rev. at 424 (citations omitted).The use of the “doctrine” in other jurisdictions has produced an incoherent and disordered body of case law as judges often have ignored the law concerning in personam jurisdiction in favor of the unbridled discretion they enjoy in dismissing cases under forum non conveniens.See Stein, Forum Non Conveniens and the Redundancy of CourtAccess Doctrine, 133 U.PaX.Rev. 781, 785 (1985) (forum non conveniens has resulted in “a crazy quilt of ad hoc, capricious, and inconsistent decisions.“). See also Stewart, Forum Non Conveniens:A Doctrine in Search of A Role, 74 Cal.L Rev. 1259, 1324 (1986) (arguing that forum non conveniens should be abolished because “[t]he factors and policies to which the doctrine calls the court's attention … are best considered in the jurisdictional contexts.“). The “considerations of fair;ness” discussed by Justice Cook may bestachieved “by following the jurisdictional rules strictly rather than construing a malleable doctrine with virtually no appellate review to negate the formal jurisdictional rules.” Note, An Economic Approach to Forum Non Conveniens Dismissals Requested by U.S. Multinational Corporations, 22 Geo.WashJ.Int'l L. & Econ. 215, 216 n. 11 (1988) [hereinafter “Economic Approach “].

9 Evidence from the most recent and largest national study ever performed regarding the pace of litigation in urban trial courts suggests that there is no empirical basis for the dissen-ters’ argument that Texas dockets will become dogged without forum non conveniens. The state of Massachusetts recognizes forum non conveniens. See Minnis v. Peebles, 24 Mass pp. 467. 510 N.E.2d 289 (1987). Conversely, the state of Louisiana has explicitly not recognized forum non conveniens since 1967. See Kassapas v. Arkon Shipping Agency, Inc., 485 So.2d 565, 567 (L App.1986), writ denied, 488 So.2d 203 (1986), cert, denied, 479 U.S. 940, 107 S.Ct. 422, 93 LEd.2d 372 (1986); Trahan v. Phoenix Ins. Co., 200 So.2d 118, 122 (La.App.1967). Nevertheless, the study revealed the median filing-to-disposition time for tort cases in Boston to be 953 days; in New Orleans, with no forum non conveniens, the median time for the dispo¬sition of tort cases was only 405 days. The study revealed the median disposition time for contract cases in Boston to be 1580 days, as opposed to a mere 271 days in New Orleans where forum non conveniens is not used. J. Goerdt, C. Lomvardias, G. Gallas & B. Mahoney, Examining Court Delay—The Pace of Litigation in 26 Urban Trial Courts, 1987 20, 22 (1989).

10 A senior vice-president of a United States multinational corporation acknowledged that “[t]he realization at corporate headquarters that liability for any [industrial] disaster would be decided in the U.S. courts, more than pressure from Third World governments, has forced companies to tighten safety procedures, upgrade plants, supervise maintenance more closely and educate workers and communities.“Wall ST. J., Nov. 26, 1985, at 22, col. 4 (quoting Harold Corbett, senior vice-president for environmental affairs at Monsanto Co.).

11 Today's opinions reveal the legal monstrosity that would be created in Texas if forum non conveniens were applied.Justice Hecht and Justice Gonzalez each predict dire consequences of a Texas without forum non conveniens. Chief Justice Phillips correctly admits that nosuch predictions can be supported. The doctrine has been developing for over 100 years, yet Justice Gonzalez asserts that the doctrine “was at best incipient among the states” until 1947. Justice Hecht states that Texas is “the only juris¬diction on earth” with the position taken today; however, earlier in the same opinion, he admits that ten states in the United States have not adopted forum non conveniens. Each of the dissenters strongly advocates forum non conveniens for Texas. However, they cannot arrive at a collective decision regarding its application. While Justice Hechr correctly acknowledges that the private interest factors are outdated and useless, Justice Gonzalez and Chief Justice Phillips advocate both the private and public interest factors. While Justice Gonzalez correctly notes that before the doctrine may be applied, jurisdiction must be proper. Justice Cook argues that the doctrine is needed to help bridge the gap in the jurisdictional rules. The conflicting views of the dissenters surely portend the confused and unpredictable decisions which would inevitably result from at-tempts by Texas trial judges to apply the doctrine

12 As one commentator observed, U.S. multinational corporations adhere to a double standard when operating abroad.The lack of stringent environmental regulations and worker safety standards abroad and the relaxed enforcement of such laws in industries using hazardous processes provide little incentive for [multinational cor-porations] to protect the safety of workers, to obtain liability insurance to guard against the hazard of product defects or toxic tort exposure, or to take precautions to minimize pollution to the environment. This double standard has caused catastrophic damages to the environment and to human lives. Note, Exporting Hazardous Industries: Should American Standards Apply?, 20 Int'l L.& Pol. 777, 780-81 (1988) (emphasis added) (footnotes omitted) [hereinafter “Exporting Hazardous Industries“]. See also Diamond, The Path of Progress Racks the Third World, N.Y. Times, Dec. 12, 1984, at Bl, col. 1.

13 A subsidiary of Sterling Drug Company advertised Winstrol, a synthetic male hormone severely restricted in the United States since it is associated with a number of side effects that the F.D.A. has called “virtually irreversible”,in a Brazilian medical journal, picturing a healthy boy and recommending the drug to combat poor appetite, fatigue and weight loss. U.S. Exports Banned, supra, 6 Intl Tr.LJ. at 96. The same company is said to have marketed Dipy-rone, a painkiller causing a fatal blood disease and characterized by the American Medical As¬sociation as for use only as “a last resort,” as “Novaldin” in the Dominican Republic. “Noval-din” was advertised in the Dominican Republic with pictures of a child smiling about its agreeable taste. Id. at 97. “In 1975, thirteen children in Brazil died after coming into contact with a toxic pesticide whose use had been severely restricted in this country.” Hazardous Exports, supra, 14 Sw.U.L.Rev. at 82.

14 Regarding Leptophos, a powerful and haz-ardous pesticide that was domestically banned, S. Jacob Scherr stated that In 1975 alone, Velsicol, a Texas-based corporation exported 3,092,842 pounds of Leptophos to thirty countries. Over half of that was shipped to Egypt, a country with no procedures for pesticide regulation or tolerance setting. In December 1976, the Washington Post reported that Leptophos use in Egypt resulted in the death of a number of farmers and illness in rural communities.But despite the accumulation of data on Leptophos’ severe neurotoxicity, Velsicol continued to market the product abroad for use on grain and vegetable crops while proclaiming the product's safety. U.S. Exports Banned, 6 Int'l Tr.LJ. at 96.

15 Less than one percent of the imported fruits and vegetables are inspected for pesticides. General Accounting Office, Pesticides: Better Sampling and Enforcement Needed on Imported Food GAO/RCED-86-219 (Sept. 26, 1986), at 3. The GAO found that of the 7.3 billion pounds of bananas imported into the F.D.A.'s Dallas Dis-trict (covering Texas) from countries other than Mexico in 1984, not a single sample was checked for illegal pesticide residues such as DBCP. Id. at 53. Even when its meager inspection program discovers illegal pesticides, the F.D.A. rarely sanctions the shipper or producer. Id. at 4. The GAO found only eight instances over a six year period where any punitive action whatsoever was taken. Id. “United States con-sumers have suffered as pesticide-treated crops are imported to the United States, thus completing a circle of poison.” McGarity, supra, 20 Tex.Int'l LJ. at 334. As just one example, from 1972 to 1976 American imports of produce from Mexico contained residues of Leptophos, the neurotoxic pesticide discussed previously at note 14. U.S. Exports Banned, supra, 6 Int'l Tr.LJ. at 97 n. 19. 1.

1 As the United States Supreme Court recently observed: [Texas] may not apply the same, or indeed, any forum non conveniens analysis…. Rather, as the Court of Appeals noted, it is possible that Texas has constituted itself the world's forum of final resort, where suit for personal injury or death may always be filed if nowhere else.” Chick Kam Choo v. Exxon Corp., 486 VS. 140, 144-45, 108 S.Ct. 1684, 1688-89, 100 LEd.2d 127, 135 (1988).

2 For example, in July 1988, there was an oil rig disaster in Scotland. A Texas lawyer went to Scotland, held a press conference, and wrote letters to victims or their families. He advised them that they had a good chance of trying their cases in Texas where awards would be much higher than elsewhere. Houston Post, July 18, 1988, at 13A, col. 1; The Times (London), July 18, 1988, at 20A, col. 1; Texas Lawyer, Sept. 26, 1988 at 3.

3 Until today, the issue of whether the legisla ture or the supreme court had abolished the doctrine of forum non conveniens was an open question.

4 See Flaiz v. Moore, 359 S.W.2d 872, 876, (Tex.1962); Couch v. Chevron International Co., Inc., 682 S.W.2d 534, 535 (Tex.1984) (per curiam). 4. See Stein, Forum Non Conveniens and the Redundancy Court Access Doctrine, 133 U.Pa.LR.781, 796 (1985) [hereinafter Stein] (“Although bearing a Latin name, the forum non conveniens doctrine is of relatively recent origin. Not until 1948 was the doctrine accepted for general application in the federal courts and it received little or no attention in the state courts until after federal adoption.”); see also Comment, Forum Non Conveniens: The Need for Legislation in Texas, 54 Texj L Rev. 737, 740 (1976).

5 The current version, section 71.031 of the Civil Practice and Remedies Code, provides:(a) An action for damages for the death or personal injury of a citizen of this state, of the United States, or of a foreign country may be enforced in the courts of this state, although the wrongful act, neglect, or default causing the death or injury takes place in a foreign state or country, if:(1) a law of the foreign state or country or of this state gives a right to maintain an action for damages for the death or injury; (2) the action is begun in this state within the time provided by the laws of this state for beginning the action; and (3) in the case of a citizen of a foreign country, the country has equal treaty rights with the United States on behalf of its citizens.(b) All matters pertaining to procedure in the prosecution or maintenance of the action in the courts of this state are governed by the law of this state. (c) The court shall apply the rules of substantive law that are appropriate under the facts of this case.

6 It makes no sense to argue that the legislature in 1913 abolished the doctrine of forum non conveniens when the doctrine was not recognized in Texas at. that time.

7 Dow and Shell contend that the legislature's use of the word “may” makes the statute permis-sive. They argue that both Kansas and Iowa have statutes similar to section 71.031 that also use the word “may” and that each applies the doctrine of forum non conveniens. Compare Kan.Stat.Ann. § 6O-217(b) (1986) and Gon-Ztrfes v. Atchinson, Topeka, and Santa Fe Ry. Co.,189 Kan. 689. 371 P.2d 193 (1962) with IOWA Code § 616.8 (1939) and Silversmith v. Ke-nosha Auto Transport, 301 N.W 2d 725, 727 (Iowa 1981). The court shuns this persuasive reasoning and chooses to hold that the language “may be enforced” in section 71.031 is mandatory thus precluding forum non conveniens dismissals.

8 The court cites Morris v. Missouri Pac R.R., 78 Tex. 17, 14 S.W. 228, 230 (1890) as authority for the proposition that Texas courts had recog-nized forum non conveniens long before Gulf Oil Corp. v. Gilbert That decision did not involve the doctrine of forum non conveniens. The Morris court never described or engaged in a balancing of public and private interest factors. Instead, the court explained the application of the doctrine of comity and affirmed the dismissal of the case by the trial court because the facts “indicate[d] the impolicy of entertaining jurisdiction … upon principles of comity.” Id. at 230. Similarly, in the cases Mexican National Ry. Co. v. Jackson, 89 Tex. 107, 33 S.W. 857 (1896), Southern Pacific Co. v. Graham, 12 Tex.Civ.App. 565, 34 S.W. 135 (1896, writ ref d), and Missouri, Kansas Texas Ry. Co. of Texas v. Godair Comm'n Co., 87 S.W. 871 (Tex.Civ.App.1905, writ refd), cited by thecourt, none of the opinions indicate that the court engaged in the discretionary balancing of public and private interest factors that is necessary in a proper forum non conveniens analysis.

9 Comity does not rely on a balancing of interest factors.Rather, it “is a willingness to grant a privilege, not as a matter of right, but out of deference and good will.“Black's Law Dictionary, 5th ed. (1979). The principles of comity are not properly equated with the doctrine of forum non conveniens.

10 Until now, Alien v. Bass has been largely ignored.Imprecise language in the opinion is, regrettably, subject to manipulation. Accordingly, I would overrule Allen v. Bass in order to eradicate any possible confusion concerning the application of forum non conveniens to actions alleged under section 71.031.

2 I also observe with interest that there may someday be a “means short of finding jurisdic-tion unreasonable” to answer the potential problem of foreign plaintiffs suing American defendants in American courts. Those means could come in the form of a federal law. In 1987, a bill was introduced in the House to amend the Judicial Code to provide specifically for removal to federal court actions commenced in state courts by foreign citizens against a United States citizen “for injury that was sustained outside the United States and relates to manufacture, purchase, sale, or use of a product outside the United States.” See H.R. 3662, 100th Cong., 1st Sess., 133 Cong.Rec. 10,785-86 (1987). In the 101st Congress, the bill was revised somewhat and has been reintroduced. See H.R. 3406, 101st Cong., 1st Sess., 135 Cong.Rec. 1124 (1989).

1 Aquilar v. Dow Chem. Co.. No. 86-4753 JGD (C.D.Cal.1986), cited in Cabalceta v. Standard fruit Co., 667 F.Supp. 833, 837, aff'd in part and rev'd in part on other grounds, 883 F.2d 1553 (11th Cir.1989).

2 Sibaja v. Dow Chemical Co., 757 F.2d 1215 (11th Cir.), cert, denied, 474 U.S. 948, 106 S.Ct. 347, 88 LEd.2d 294 (1985); Cabalceta v. Standard Fruit Co., 667 F.Supp. 833 (S.D.Fla.1987), aff'd in part and rev'd in part on other grounds, 883 F.2d 1553 (11th Cir.1989) (holding that if the district court had jurisdiction of the action removed from state court, its dismissal on the grounds of forum non conveniens was appropriate, and that if it did not, the action must be remanded to state court).

3 Gulf Oil Co. v. Gilbert, 330 U.S. 501, 67 S.Ct. 839, 91 L.Ed. 1055 (1947); Piper Aircraft Co. v. Reyno, 454 U.S. 235, 102 S.Ct. 252, 70 L.Ed.2d 419 (1981).

4 Milb v. Aetna Fire Underwriters Ins. Co., 511 A.2d 8 (D.C.1986).

5 Crowson v. Sealaska Corp., 705 P.2d 905 (Alas- ka 1985); Avila v. Chamberlain, 119 Ariz. 369, 580 P.2d 1223 (1978);Running v. Southwest Freight Lines, 227 Ark. 839, 303 S.W.2d 578 (1957); Archibald v. Cinerama Hotels, 15 Cal.3d 853,126 CaLRptr. 811, 544 P.2d 947 (1976); State v. District Court, 635 P.2d 889 (Colo. 1981); Miller v. United Technologies Corp., 40 Conn. Supp. 457, 515 A.1d 390 (1986);State Marine Lines v.Domingo, 269 A.2d 223 (Del.1970); Houston v. Caldwell, 359 So.2d 858 (Fla.1978); Allen v. Allen, 64 Haw. 553, 645 P.2d 300 (1982); Jones v. Searles Laboratories, 93 Id 366, 67IlLDec. 118, 444 N.E.2d 157 (1982); McCrocken v. Eli Lilly ii Co., 494 N.E.2d 1289 (Ind.CLApp. 1986); Silversmith v. Kenosha Auto Transport, 301 N.W.2d 725 (Iowa 1981); Quittin v. Hesston Corp., 230 Kan. 591, 640 PJd 1195 (1982); Carter v. Netherton, 302 S.W.2d 382 (Ky.1957); Stewart v. Litchenberg, 148 La. 195, 86 So. 734 (1920); Foss v. Richards, 126 Me. 419, 139 A. 313 (1927); Texaco v. Vanden Bosche, 242 Md. 334, 219 AJd 80 (1966); My v. Albert Laroque Lumber Ltd., 397 Mass. 43, 489 N.2Ed 698 (1986); Anderson v. Great Lakes Dredge & Dock Co., 411 Mich. 619, 309 N.W.2d 539 (1981); Johnson v. Chicago, Burlington & Quincy R.R., 243 Minn. 58, 66 N.WJ2d 763 (1954); Illinois Cent. Rd. Co. v. Moore, 215 So.2d 419 (Miss. 1968); Besse v. Missouri Pacific R.R., 721 S.W.2d 740 (Mo. 1986), cert, denied, 481 US. 1016, 107 S.Ct. 1894, 95 LEd.2d 501 (1987); Qualley v. Chrysler Credit Corp., 191 Neb. 787,217 N.W.2d 914 (1974); Payne v. Eighth Jud. Dis Court, 97 Nev. 228. 626 2A 1278 (1981); Van Dam v. Smit, 101 N.H. 508, 148 AJd 289 (1959); Gore v. United States Steel Corp., 15 N.H. 301, 104 AOd 670, cert, denied, 348 US. 861, 75 S.Ct. 84, 99 LEd. 678 (1954); McLam v. McLam, 85 N.M. 196, 510 P.2d 914 (1973); Islamic Republic of Iran v. Pahlavi, 62 N.Y.2d 474, 478 N.Y.S.2d 597, 467 N.E.2d 245 (1984); Motor Inn MgmL, Inc. v. Irvin-Fuller Dev. Co., 46 N.CApp. 707, 266 S.E.2d 368, review denied, 301 N.C. 93, 273 S.E.2d299 1980); N.D.R.CIVJRO. 4(b)(5); Chambers v. Merrell-Dow Pharm., 35 Ohio St.3d 123, 519 N.E.2d 370 (1988); Groendyke Transp., Inc. v. Cook, 594 P.2d 369 (Okla.1979); Homer v. Pleasant Creek Mining Corp., 165 Or 683, 107 P.2d 989 (1940); Rini v. New York Cent R.R. Co., 429 Pa. 235, 240 A.2d 372 (1968); Braten Apparel Corp. v. Bankers Trust Co., 273 S.C. 663, 259 S.E.2d 110 (1979); Zurick v. Inman, 221 Tenn. 393, 426 S.W.2d 767 (1968); Kish v. Wright, 562 P.2d 625 (Utah 1977); Burrington v.Ashland Oil. Co., 134 Vt 211, 356 A 2d 506 (1976); Werner v. Werner, 84 Washed 360, 526 P.2d 370 (1974); Wisstat-ann. § 262.19.

6 Of the nine states that have not recognized the rule of forum non conveniens, none have rejected it absolutely as the Court does today. As discussed below, Alabama did reject the rule of forum non conveniens at one time but has since recognized it by statute. Montana has refused to apply the rule of forum non conveniens in actions under the Federal Employers’ Liability Act, 45 U.S.C. §§ 51-60 (1986), but has expressly reserved the issue of the applicability of the rule to other actions. Labtlla v. Burlington North-em, Inc., 182 Mont 202, 595 2d 1184, 1187 (1979). An Idaho appellate court has suggested that the rule would apply in appropriate cases. Nelson v. Worldwide Lease, Inc., 110 Idaho 369, 716 V2d 513, 518 n. 1 (App.1986). Georgia, like Montana, would not apply the rule in FELA cases, see Brown v. Seaboard Coast Lines R.R., 229 Ga. 481, 192 SE 2d 382, 383 (1972), but has suggested that it might apply in other cases, Smith v. Board of Regents, 165 Ga-App. 565, 302 S.E.2d 124, 125 (1983). West Virginia also declines to apply the rule in FELA cases, but has not expressly ruled on its application in other contexts.Gardner v. Norfolk and W.Ry. Co., — W.Va., 372 S.E 2d 786 (W.Va.1988). Connecticut has applied forum non conveniens factors in a case without referring to the rule by name. Miller v. United Technologies Corp., 40 Conn-Supp, 457, 515 A 2d 390 (1986). Wyoming has not resolved the issue. Booth v. Magee Carpet Co., 548 PJd 1252, 1255 n.2 (Wyo.1976). Alaska has refused to reject one case on grounds of forum non conveniens, but did not absolutely reject the rule in all cases. Crowson v. Sealaska Corp., 705 P.2d 905 (Alaska 1985). Virginia, Rhode Island and South Dakota do not appear to have considered application of the rule.

7 The original act provided “[t]hat whenever the death or personal injury of a citizen of this State or of a country having equal treaty rights with the United States on behalf of its citizens, has been or may be caused by a wrongful act, neglect or default in any State, for which a right to maintain an action and recover damages in re-spect thereof is given by a statute or by law of such State, territory or foreign country, such right of action may be enforced in the courts of the United States, or in the courts of. this State, within the time prescribed for the commence-ment of such action by the statute of this State, and the law of the former shall control in themaintenance of such action in all matters [per-taining] to procedure.” Act of Apr. 8, 1913, ch. 161. 1913 Tex.Gen.Laws 338-339, repealed by Revised Statutes, § 2, 1925 Tex.Rev.Civ.Stat. 2419. This act was amended in 1917 to apply to citizens of the United States as well as of this State and foreign countries, and to clarify that the actionable injury could occur not only in another state but also in a foreign country. Act of March 30, 1917, ch. 156, 1917 Tex.Gen.Uws 365, repealed by Revised Statutes, § 2, 1925 Tex. Rev.Civ.Stat. 2419.

8 Justice Doggett's concurring opinion objects that this analysis does not give proper deference to the doctrine of stare decisis. Justice Dooobit did not defend the doctrine quite so vigorously in his very first opinion as a member of this Court, which overruled two prior decisions of this Court.Sterner v. Marathon Oil Co., 767 S.W.2d 686, 690 (Tex.1989) (overruling, in part, Sakowitz. Inc. v. Steck, 669 S.W.2d 105 (Tex. 1984), and Black Lake Pipe Line Co. v. Union Construction Co., 538 S.WJd 80 (Tex.1976). Stare decisis cannot save Allen v. Bass. Its language simply cannot coexist consistently with Couch.

9 The issue for the Court is not whether the Legislature should have abolished forum non conveniens, but whether it did.If it did, it surely must be presumed to have acted in the best interests of the people of Texas. The purpose of examining the public policies which support the rule of forum non conveniens is not to argue for retention of the rule but to show that the Legislature would not be motivated to abolish the rule.

10 It is equally plain to me that defendants want to be sued in Costa Rica rather than Texas because they expect that their exposure will be less there than here. However, it also seems plain to me that the Legislature would want to protect the citizens of this state, its constituents, from greater exposure to liability than they would face in the country in which the alleged wrong was committed. This would be incentive for the Legislature not to abolish the rule of forum non conveniens.

11 Justice Dogceit's concurring opinion undertakes to answer these questions that the Court ignores. It suggests that there are essentially two policy reasons to abolish the rule of forum non conveniens: to assure that injured plaintiffs can recover fully, and to assure that American corporations will be fully punished for their misdeeds abroad. Neither reason is sufficient If the defendants in this case were Costa Rican corporations which plaintiffs could sue only in Costa Rica, plaintiffs would be limited to whatever recovery they could obtain in Costa Rican courts.The concurring opinion has not ex-plained why Costa Rican plaintiffs who claim to have been injured by American corporations are unjustly treated if they are required to sue in their own country where they could only sue if they had been injured by Costa Rican corporations. In other words, why are Costa Ricans injured by an American defendant entitled to any greater recovery than Costa Ricans injured by a Costa Rican defendant, or a Libyan defendant, or an Iranian defendant? Moreover, the concurring opinion does not explain why the American justice system should undertake to punish American corporations more severely for their actions in a foreign country than that country does. If the alleged conduct of the defendants in this case is so egregious, why has Costa Rica not chosen to afford its own citizens the recovery they seek in Texas? One wonders how receptive Costa Rican courts would be to the pleas of American plaintiffs against Costa Rican citizens* for recovery of all the damages that might be available in Texas, or anywhere else for that matter.

1 This statute is authorized by Article V, section 3-b of the Texas Constitution.