Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

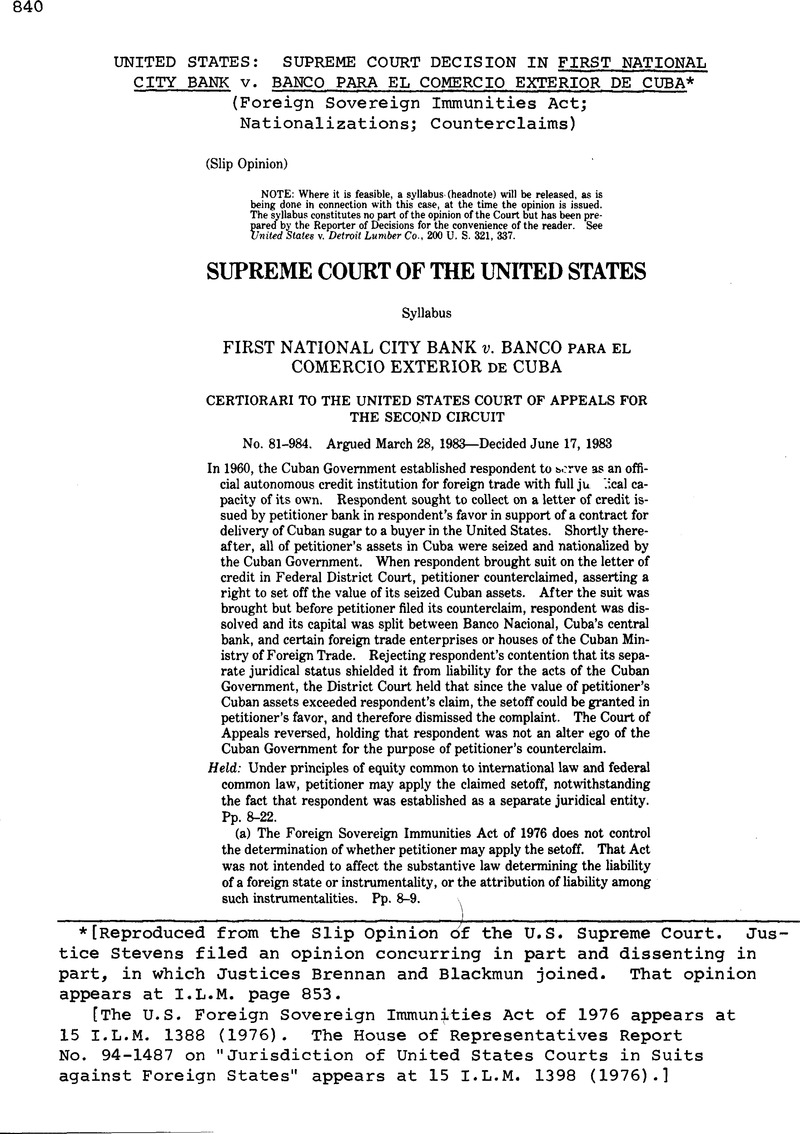

[Reproduced from the Slip Opinion df the U.S.Supreme Court.Justice Stevens filed an opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part, in which Justices Brennan and Blackmun joined. That opinion appears at I.L.M. page 853.

[The U.S. Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976 appears at 15 I.L.M. 1388 (1976). The House of Representatives Report No. 94-1487 on “Jurisdiction of United States Courts in Suits against Foreign States” appears at 15 I.L.M. 1398 (1976).]

1 Law No. 934 provides that “[a]ll the functions of a mercantile character heretofore assigned to [Bancec] are hereby transferred and vested in the foreign trade enterprises or houses set up hereunder, which are subrogated to the rights and obligations of said former Bank in pursuance of the assignment of those functions ordered by the Minister.” App. to Pet. for Cert. 24d.

2 Citibank’s answer alleged that the suit was “brought by and for the benefit of the Republic of Cuba by and through its agent and wholly-owned instrumentality,. . . which is in fact and in law and in form and function an integral part of and indistinguishable from the Republic of Cuba.” App. 113.

3 The bulk of the evidence at trial was directed to the question whether the value of Citibank’s confiscated branches exceeded the amount Citibank had already recovered from Cuba, including a setoff it had successfully asserted in Banco National de Cuba v. First National City Bank, 478 F. 2d 191 (CA2 1973) (Banco I), the decision on remand from this Court’s decision in First National City Bank v. Banco National de Cuba, 406 U. S. (1972). Only one witness, Raul Lopez, testified on matters touching upon the question presented. (A second witness, Juan Sanchez, described the operations of Bancec’s predecessor. App. 185-186.) Lopez, who was called by Bancec, served as a lawyer for Banco Nacional from 1953 to 1965, when he went to work for the Foreign Trade Ministry. He testified that “Bancec was an autonomous organization that was supervised by the Cuban government but not controlled by it.” App. 197. According to Lopez, under Cuban law Bancec had independent legal status, and could sue and be sued. Lopez stated that Bancec’s capital was supplied by the Cuban government and that its net profits, after reserves, were paid to Cuba’s Treasury, but that Bancec did not pay taxes to the Government. Id., at 196.

The District Court also took into evidence translations of the Cuban statutes and resolutions, as well as the July 1961 stipulation for leave to file a motion to file an amended complaint substituting the Republic of Cuba as plaintiff. The court stated that the stipulation would be taken “for what it is worth,” and acknowledged respondent’s representation that it was based on an “erroneous” interpretation of Cuba’s law. Id., at 207-209.

4 Judge van Pelt Bryan, before whom the case was tried, died before issuing a decision. With the parties’ consent, Judge Brieant decided the case based on the record of the earlier proceedings. 505 F. Supp. 412, 418 (1980).

5 The District Court stated that the events surrounding Bancec’s dissolution “naturally inject a question of ‘real party in interest’ into the discussion of Bancec’s claim,” but it attached “no significance or validity to arguments based on that concept.” 505 F. Supp., at 425. It indicated that when Bancec dissolved, the claim on the letter of credit was “the sort of asset, right and claim peculiar to the banking business, and accordingly, probably should be regarded as vested in Banco Nacional. . . . “ Id., at 424. Noting that the Court of Appeals, in Banco I, had affirmed a ruling that Banco Nacional could be held liable by way of setoff for the value of Citibank’s seized Cuban assets, the court concluded:

“[T]he devolution of [Bancec’s] claim, however viewed, brings it into the hands of the Ministry, or Banco Nacional, each an alter ego of the Cuban Government. . . . [W]e accept the present contention of plaintiff’s counsel that the order of this Court of July 6th [1961] permitting, but apparently not requiring, the service of an amended complaint in which the Republic of Cuba itself would appear as a party plaintiff in lieu of Bancec was based on counsel’s erroneous assumption, or an erroneous interpretation of the laws and resolutions providing for the devolution of the assets of Bancec. Assuming this to be true, it is of no moment. The Ministry of Foreign Trade is no different than the Government of which its minister is a member.” Id., at 425 (emphasis in original).

6 In a footnote, the Court of Appeals referred to Bancec’s dissolution and listed its successors, but its opinion attached no significance to that event. 658 F. 2d, at 916, n. 4.

7 In relevant part, 28 U. S. C. § 1607 provides:

“In any action brought by a foreign state . . . in a court of the United States or of a State, the foreign state shall not be accorded immunity with respect to any counterclaim—

. . . . .

(c) to the extent that the counterclaim does not seek relief exceeding in amount or differing in kind from that sought by the foreign state.”

As used in 28 U. S. C. § 1607, a “foreign state” includes an “agency or instrumentality of a foreign state. . . .“ 28 U. S. C. § 1603(a).

Section 1607(c) codifies our decision in National City Bank v. Republic of China, 348 U. S. 356 (1955). See H. R. Rep. No. 94-1487, p. 23 (1976).

8 See also H. R. Rep. No. 94-1487, p. 28 (in deciding whether property in the United States of a foreign state is immune from attachment and execution under 28 U. S. C. § 1610(a)(2), “[t]he courts will have to determine whether property ‘in the custody of an agency or instrumentality is property ‘of’ the agency or instrumentality, whether property held by one agency should be deemed to be property of another, [and] whether property held by an agency is property of the foreign state.”)

9 See also Hadari, The Choice of National Law Applicable to the Multinational Enterprise and the Nationality of Such Enterprises, 1974 Duke L. J. 1, 15-19.

10 Cf. anderson v. Abbott, 321 U. S. 349, 365 (1944) (declining to apply the law of the state of incorporation to determine whether a banking corporation complied with the requirements of federal banking laws because “no State may endow its corporate creatures with the power to place themselves above the Congress of the United States and defeat the federal policy concerning national banks which Congress has announced”).

11 Pointing out that 28 U. S. C. § 1606, see ante, at 8-9, contains language identical to the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA), 28 U. S. C. § 2674 (1976 ed.), Bancec also contends alternatively that the FSIA, like the FTCA, requires application of the law of the forum state—here New York—including its conflicts principles. We disagree. Section 1606 provides that “[a]s to any claim for relief with respect to which a foreign state is not entitled to immunity. . . , the foreign state shall be liable in the same manner and to the same extent as a private individual in like circumstances.” Thus, where state law provides a rule of liability governing private individuals, the FSIA requires the application of that rule to foreign states in like circumstances. The statute is silent, however, concerning the rule governing the attribution of liability among entities of a foreign state. In Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U. S. 398, 425 (1964), this Court declined to apply the State of New York’s act of state doctrine in a diversity action between a United States national and an instrumentality of a foreign state, concluding that matters bearing on the nation’s foreign relations “should not be left to divergent and perhaps parochial state interpretations.” When it enacted the FSIA, Congress expressly acknowledged “the importance of developing a uniform body of law” concerning the amenability of a foreign sovereign to suit in United States courts. H. R. Rep. No. 94-1487, p. 32. See Verlinden B.V. v. Central Bank of Nigeria, U. S., (1983). In our view, these same considerations preclude the application of New York law here.

12 Although this Court has never been required to consider the separate status of a foreign instrumentality, it has considered the legal status under federal law of United States government instrumentalities in a number of contexts, none of which are relevant here. See e. g., Keifer & Keifer v. Reconstruction Finance Corp., 306 U. S. 381 (1939) (determining that Congress did not intend to endow corporations chartered by the Reconstruction Finance Corporation’ with immunity from suit).

13 Friedmann, , “Government Enterprise: A Comparative Analysis” in Government Enterprise: A Comparative Study 306–307 (Friedmann, W. & Garner, J.F. eds. 1970)Google Scholar. See Coombes, D., State Enterprise: Business or Politics? (1971) (United Kingdom)Google Scholar; Dallmayr, , Public and Semi-Public Corporations in France, 26 Law & Contemp. Prob. 755 (1961)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Quigley, J., The Soviet Foreign Trade Monopoly 48-49, 119–120 (1974)Google Scholar; Seidman, , “Government-sponsored Enterprise in the United States,” in The New Political Economy 85 (Smith, B. ed. 1975)Google Scholar; Supranowitz, , The Law of State-Owned Enterprises in a Socialist State, 26 Law & Contemp. Prob. 794 (1961)Google Scholar; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Organization, Management and Supervision of Public Enterprises in Developing Countries 63-69 (1974) (hereinafter United Nations Study); Walsh, A.H., The Public’s Business: The Politics and Practices of Government Corporations 313–321 (1978) (Europe)Google Scholar.

14 Friedmann, supra, at 334; United Nations Study, supra, at 63-65.

15 President Franklin D. Roosevelt described the Tennessee Valley Authority, perhaps the best known of the American public corporations, as “a corporation clothed with the power of government but possessed of the flexibility and initiative of a private enterprise.” 77 Cong. Rec. 1423 (1933). See also Thurston, J., Government Proprietary Corporations in the English-Speaking Countries 7 (1937)Google Scholar.

16 J. Thurston, supra, at 43-44. This principle has long been recognized in courts in common law nations. See Bank of the United States v. Planters’ Bank of Georgia, 9 Wheat. 904 (1824); Tamlin v. Hannaford, [1950] 1 K. B. 18, 24 (C. A.).

17 See Posner, , The Rights of Creditors of Affiliated Corporations, 43 U. Chi. L. Rev. 499, 516-517 (1976)Google Scholar (discussing private corporations).

18 The British courts, applying principles we have not embraced as universally acceptable, have shown marked reluctance to attribute the acts of a foreign government to an instrumentality owned by that government. In I Congreso del Partido, [1983] A. C. 244, a decision discussing the socalled “restrictive” doctrine of sovereign immunity and its application to three Cuban state-owned enterprises, including Cubazucar, Lord Wilberforce described the legal status of government instrumentalities:

“State-controlled enterprises, with legal personality, ability to trade and to enter into contracts of private law, though wholly subject to the control of their state, are a well-known feature of the modern commercial scene. The distinction between them, and their governing state, may appear artificial: but it is an accepted distinction in the law of English and other states. Quite different considerations apply to a state-controlled enterprise acting on government directions on the one hand, and a state, exercising sovereign functions, on the other.” Id., at 258 (citation omitted).

Later in his opinion, Lord Wilberforce rejected the contention that commercial transactions entered into by state-owned organizations could be attributed to the Cuban government. “The status of these organizations is familiar in our courts, and it has never been held that the relevant state is in law answerable for their actions.” Id., at 271. See also Trendtex Trading Corp v. Central Bank of Nigeria, [1977] Q. B. 529 in which the Court of Appeal ruled that the Central Bank of Nigeria was not an “alter ego or organ” of the Nigerian government for the purpose of determining whether it could assert sovereign immunity. Id., at 559.

In C. Czarnikow, Ltd. v. Rolimpex, [1979] A. C. 351, the House of Lords affirmed a decision holding that Rolimpex, a Polish state trading enterprise that sold Polish sugar overseas, could successfully assert a defense of force majeure in an action for breach of a contract to sell sugar. Rolimpex had defended on the ground that the Polish government had instituted a ban on the foreign sale of Polish sugar. Lord Wilberforce agreed with the conclusion of the court below that, in the absence of “clear evidence and definite findings” that the foreign government took the action “purely in order to extricate a state enterprise from contractual liability,” the enterprise cannot be regarded as an organ of the state. Rolimpex, he concluded, “is not so closely connected with the government of Poland that it is precluded from relying on the ban [on foreign sales] as government intervention. . . . “ Id., at 364.

19 See 1 W. M. Fletcher, Cyclopedia of the Law of Private Corporations § 41 (rev. perm ed. 1974):

“[A] corporation will be looked upon as a legal entity as a general rule, and until sufficient reason to the contrary appears; but, when the notion of legal entity is used to defeat public convenience, justify wrong, protect fraud, or defend crime, the law will regard the corporation as an association of persons.” Id., at 166 (footnotes omitted).

See generally, H. Henn, Handbook of the Law of Corporations § 146 (2d ed. 1970); I.M. Wormser, Disregard of the Corporate Fiction and Allied Corporate Problems 42-85 (1927).

20 In Case Concerning The Barcelona Traction, Light & Power Co., 1970 I.C. J. 3, the International Court of Justice acknowledged that, as a matter of international law, the separate status of an incorporated entity may be disregarded in certain exceptional circumstances:

“Forms of incorporation and their legal personality have sometimes not been employed for the sole purposes they were intended to serve; sometimes the corporate entity has been unable to protect the rights of those who have entrusted their financial resources to it; thus inevitably there have arisen dangers of abuse, as in the case of many other institutions of law. Here, then, as elsewhere, the law, confronted with economic realities, has had to provide protective measures and remedies in the interests of those within the corporate entity as well as those outside who have dealings with it: the law has recognized that the independent existence of the legal entity cannot be treated as an absolute. It is in this context that the process of ‘lifting the corporate veil’ or ‘disregarding the legal entity’ has been found justified and equitable in certain circumstances or for certain purposes. The wealth of practice already accumulated on the subject in municipal law indicates that the veil is lifted, for instance, to prevent misuse of the privileges of legal personality, as in certain cases of fraud or malfeasance, to protect third persons such as a creditor or purchaser, or to prevent the evasion of legal requirements or of obligations.

. . . . .

In accordance with the principle expounded above, the process of lifting the veil, being an exceptional one admitted by municipal law in respect of an institution of its own making, is equally admissible to play a similar role in international law. . . . “ Id., at 38-39.

On the application of these principles by European courts, see Cohn, and Simitis, , “Lifting the Veil” in the Company Laws of the European Continent, 12 Int. & Comp. L.Q. 189 (1963)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Hadari, , The Structure of the Private Multinational Enterprise, 71 Mich. L. Rev. 729, 771, n. 260 (1973)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

21 Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 4 Wheat. 514, 636 (1819).

22 Pointing to the parties’ failure to seek findings of fact in the District Court concerning Bancec’s dissolution and its aftermath, Bancec contends that the District Court’s order denying its motion to substitute Cubazucar as plaintiff precludes further consideration of the effect of the dissolution. While it is true that the District Court did not hear evidence concerning which agency or instrumentality of the Cuban Government, under Cuban law, succeeded to Bancec’s claim against Citibank on the letter of credit, resolution of that question has no bearing on our inquiry. We rely only on the fact that Bancec was dissolved by the Cuban Government and its assets transferred to entities that may be held liable on Citibank’s counter-claim—undisputed facts readily ascertainable from the statutes and orders offered in the District Court by Bancec in support of its motion to substitute Cubanzucar.

23 Law No. 930, the law dissolving Bancec, contains the following recitations:

“WHEREAS, the measures adopted by the Revolutionary Government in pursuance of the Program of the Revolution have resulted, within a short time, in profound social changes and considerable institutional transformations of the national economy.

“WHEREAS, among these institutional transformations there is one which is specially significant due to its transcendence in the economic and financial fields, which is the nationalization of the banks ordered by Law No. 891, of October 13,1960, by virtue of which the banking functions will hereafter be the exclusive province of the Cuban Government.

“WHEREAS, the consolidation and the operation of the economic and social conquests of the Revolution require the restructuration into a sole and centralized banking system, operated by the State, constituted by the [Banco Nacional], which will foster the development and stimulation of all productive activites of the Nation through the accumulation of the financial resources thereof, and their most economic and reasonable utilization....” App. to Pet. for Cert. 14d-15d.

24 The parties agree that, under the Cuban Assets Control Regulations, 31 CFR Part 515 (1982), any judgment entered in favor of an instrumentality of the Cuban Government would be frozen pending settlement of claims between the United States and Cuba.

25 See also Banco Nacional de Cuba v. First National City Bank, supra, 406 U. S., at 770-773 (Douglas, J., concurring in the result); Federal Republic of Germany v. Elicofon, 358 F. Supp. 747 (EDNY 1972), aff’d, 478 F. 2d 231 (CA2 1973), cert, denied, 415 U. S. 931 (1974). In Elicofon, the District Court held that a separate juridical entity of a foreign state not recognized by the United States may not appear in a United States court. A contrary holding, the court reasoned, “would permit non-recognized governments to use our courts at will by creating ‘juridical entities’ whenever the need arises.” 358 F. Supp., at 757.

26 See Banco I, supra, 478 F. 2d, at 194.

27 The District Court adopted, and both Citibank and the Solicitor General urge upon the Court, a standard in which the determination whether or not to give effect to the separate juridical status of a government instrumentality turns in part on whether the instrumentality in question performed a “governmental function.” We decline to adopt such a standard in this case, as our decision is based on other grounds. We do observe that the concept of a “usual” or a “proper” governmental function changes over time and varies from nation to nation. Cf. New York v. United States, 326 U. S. 572, 580 (1945) (opinion of Frankfurter, J.) (“To rest the federal taxing power on what is ‘normally’ conducted by private enterprise in contradiction to the ‘usual’ governmental functions is too shifting a basis for determining constitutional power and too entangled in expediency to serve as a dependable legal criterion”); id., at 586 (Stone, C. J., concurring); id., at 591 (Douglas, J., dissenting). See also Friedmann, The Legal Status and Organization of the Public Corporation, 16 Law & Contemp. Prob. 576, 589-591 (1951).

28 Bancec does not suggest, and we do not believe, that the act of state doctrine, see e. g., Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U. S. 398 (1964), precludes this Court from determining whether Citibank may set off the value of its seized Cuban assets against Bancec’s claim. Bancec does contend that the doctrine prohibits this Court from inquiring into the motives of the Cuban Government for incorporating Bancec. Brief for Respondent 16-18. We need not reach this contention, however, because our conclusion does not rest on any such assessment.

1 Law No. 930 provided, in part, that Bancec’s “trade functions will be assumed by the foreign trade enterprises or houses of the Ministry of Foreign Trade,” App. to Pet. for Cert. 16d, App. 104. Law No. 934, correspondingly, stated, “All the functions of a mercantile character heretofore assigned to said Foreign Trade Bank of Cuba are hereby transferred and vested in the foreign trade enterprises or houses set up hereunder, which are subrogated to the rights and obligations of said former Bank in pursuance of the assignment of those functions ordered by the Minister.” App. to Pet. for Cert. 24d. The preamble of Resolution No. 1 of 1961, issued on March 1, 1961, explained that Law No. 934 had provided “that all functions of a commercial nature that were assigned to the former Cuban Bank for Foreign Trade are attributed to the enterprises or foreign trade houses which are subrogated in the rights and obligations of said Bank.” Nothing in the affidavit filed by respondent in May 1975 elucidates the precise nature of these transactions, or explains how Bancec’s former trading functions were exercised during the six-day interval. App. 132-137.

1 Nor do I agree that a contrary result “would cause such an injustice.” Ante, at 21. Petitioner is only one of many American citizens whose property was nationalized by the Cuban Government. It seeks to minimize its losses by retaining $193,280.30 that a purchaser of Cuban sugar had deposited with it for the purpose of paying for the merchandise, which was delivered in due course. Having won this lawsuit, petitioner will simply retain that money. If petitioner’s contentions in this case had been rejected, the money would be placed in a fund comprised of frozen Cuban assets, to be distributed equitably among all the American victims of Cuban nationalizations. Ante, at 20, n. 24. Even though petitioner has suffered a serious injustice at the hands of the Cuban Government, no special equities militate in favor of giving this petitioner a preference over all other victims simply because of its participation in a discrete, completed, commercial transaction involving the sale of a load of Cuban sugar.