No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

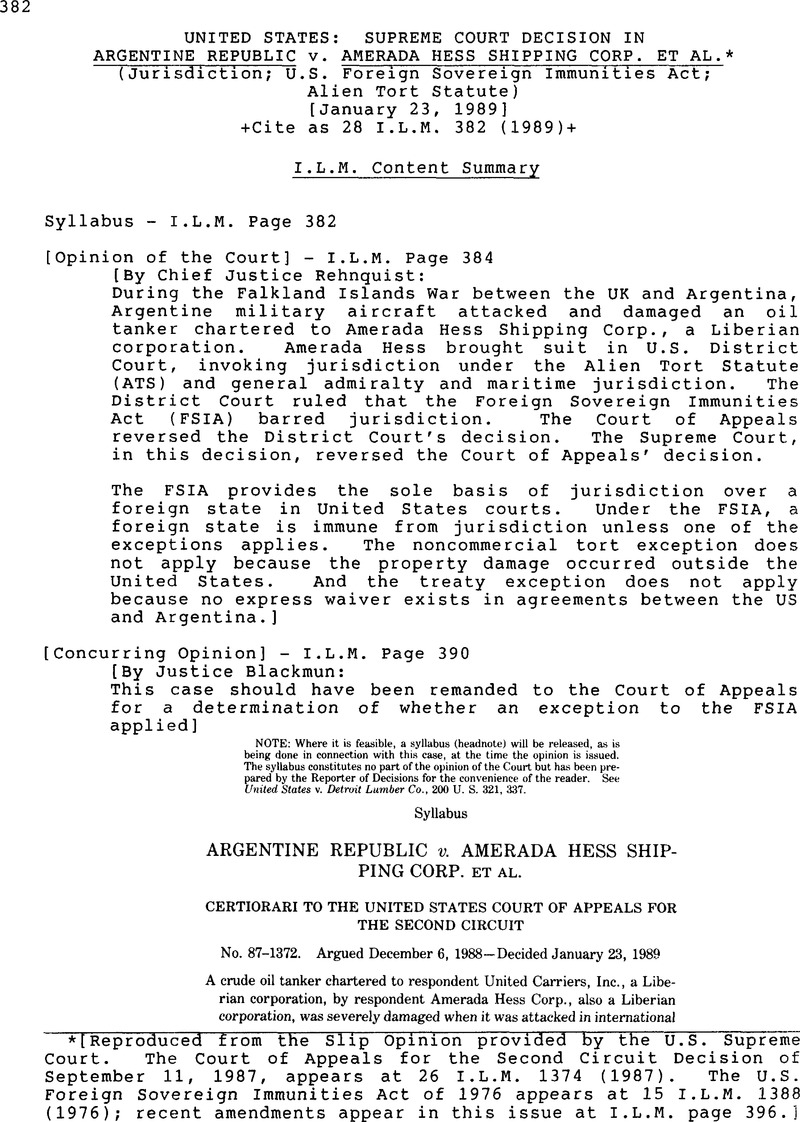

United States: Supreme Court Decision in Argentine Republic v. Amerada Hess Shipping Corp. et.al.(Jurisdiction; U.S. Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act; Alien Tort Statute)

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1989

References

* [Reproduced from the Slip Opinion provided By the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Decision of September 11, 1987, appears at 26 I.L.M.1374 (1987).The U.S.Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976 appears at 15 I.L.M.1388 (1976); recent amendments appear in this issue at I.L.M.page 396.]

1 From the Nation's founding until 1952, foreign states were “generally granted … complete immunity from suit” in United States courts, and the Judicial Branch deferred to the decisions of the Executive Branch on such questions. Verlinden B.V.v. Central Bank of Nigeria, 461 U.S. 480, 486 (1983). In 1952, the State Department adopted the view that foreign states could be sued in United States courts for their commercial acts, but not for their public acts. Id., at 487. “For the most part,” the FSIA “codifies” this so-called “restrictive” theory of foreign sovereign immunity. Id., at 488.

2 Respondents did not invoke the District Court's jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1330(a).They did, however, serve their complaints upon petitioner's Ministry of Foreign Affairs in conformity with the service of process provisions of 28 U.S.C. § 1608(a) of the FSIA, and the regulations promulgated thereunder by the Department of State, 22 CFR pt. 93 (1986). See App. to Pet. for Cert. 38a, 41a.

3 ‘Subsection (b) of 28 U.S.C. § 1330 provides that “[p]ersonal jurisdiction over a foreign state shall exist as to every claim for relief over which the district courts have [subject-matter] jurisdiction under subsection (a) where service has been made under [28 U.S.C. § 1608].” Thus, personal jurisdiction, like subject-matter jurisdiction, exists only when one of the exceptions to foreign sovereign immunity in §§ 1605-1607 applies. Verlinden, supra, at 485, 489, and n. 14. Congress’ intention to enact a comprehensive statutory scheme is also supported by the inclusion in the FSIA of provisions for venue, 28 U.S.C. § 1391(f), removal, §1441(d), and attachment and execution, §§ 1609-1611. Our conclusion here is supported by the FSIA's legislative history. See, e.g., H.R. Rep.No. 94-1487, p. 12 (1976) (H.R.Rep.); S. Rep.No. 94-1310, pp. 11-12 (1976) (S. Rep.) (FSIA “sets forth the sole and exclusive standards to be used in resolving questions of sovereign immunity raised by sovereign states before Federal and State courts in the United States,” and “prescribes … the jurisdiction of U.S. district courts in cases involving foreign states“).

4 ’ See Von Dardel v. Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, 623 F. Supp. 246 (DC 1985) (alternative holding). The Court of Appeals did cite its earlier decision in Filartiga v. Pena-Irala, 630 F. 2d 876 (CA2 1980), which involved a suit under the Alien Tort Statute by a Paraguayan national against a Paraguayan police official for torture; the Paraguayan Government was not joined as a defendant.

5 The FSIA amended the diversity statute to delete references to suits in which a “foreign stat[e]” is a party either as plaintiff or defendant, see 28 U.S.C. §§ 1332(a)(2) and (3) (1970), and added a new paragraph (4) that preserves diversity jurisdiction over suits in which foreign states are plaintiffs. As the legislative history explained, “[s]ince jurisdiction in actions against foreign states is comprehensively treated by the new section 1330, a similar jurisdictional basis under section 1332 becomes superfluous.” H.R. Rep., at 14; S.Rep.,at 13. Unlike the diversity statute, however, the Alien Tort Statute and the other statutes conferring jurisdiction in general terms on district courts cited in the text did not in 1976 (or today) expressly provide for suits against foreign states.

6 The Court of Appeals majority did not pass on whether any of exceptions to the FSIA applies here. It did note, however, that respondents’ arguments regarding § 1605(a)(5) were consistent with its disposition of the case. 830 F.2d, at 429, n.3. The dissent found none of the FSIA's exceptions applicable on these facts. Id., at 430 (Kearse, J. dissenting).

7 'See, e.g., 14 U.S.C. §89(a) (empowering Coast Guard to search and seize vessels “upon the high seas and waters over which the United States has jurisdiction” for “prevention, detection, and suppression of violations of laws of the United States“); 18 U.S.C. § 7 (“special maritime and territorial jurisdiction of the United States” in Federal Criminal Code extends to United States vessels on “[t]he high seas, any other waters within the admiralty and maritime jurisdiction of the United States, and out of the jurisdiction of any particular State“); 19 U.S.C. § 1701 (permitting President to declare portions of “high seas” as customs-enforcement areas).

8 The United States has historically adhered to a territorial sea of three nautical miles, see United States v. California, 332 U.S. 19, 32-34 (1947), although international conventions permit a territorial sea of up to 12 miles. See 2 Restatement (Third) of Foreign Relations Law of United States § 511 (1987). On December 28, 1988, the President announced that the United States would henceforth recognize a territorial sea of 12 nautical miles. See Presidential Proclamation, No. 5928, 54 Fed. Reg. 777 (1989).

9 ‘Section 1605(a)(2) provides, in pertinent part, that foreign states shall not be immune from the jurisdiction United States courts in cases “in which the action is based … upon an act outside the territory of the United States in connection with a commercial activity of the foreign state else where and that act causes a direct effect in the United States.

10 ” ‘“Article 22(1), (3), of the Geneva Convention on the High Seas, 13 U.S.T., at 2318-2319, for example, states that a warship may only board a merchant ship if it has a “reasonable ground for suspecting” the merchant ship is involved in piracy, the slave trade, or traveling under false colors. If an inspection fails to support the suspicion, the merchant ship “shall be compensated for any loss or damage that may have been sustained.” Article 23 contains comparable provisions for the stopping of merchant ships by aircraft. Similarly, Article 1 of the Pan-American Maritime Neutrality Convention, 47 Stat., at 1990, 1994, permits a warship to stop a merchant ship on the high seas to determine its cargo, and whether it has committed “any violation of blockade,” but the warship may only use force if the merchant ship “fails to observe the instructions given it.” Article 27 provides that “[a] belligerent shall indentify the damage caused by its violation of the foregoing provisions. It shall likewise be responsible for the acts of persons who may belong to its armed forces.“