No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

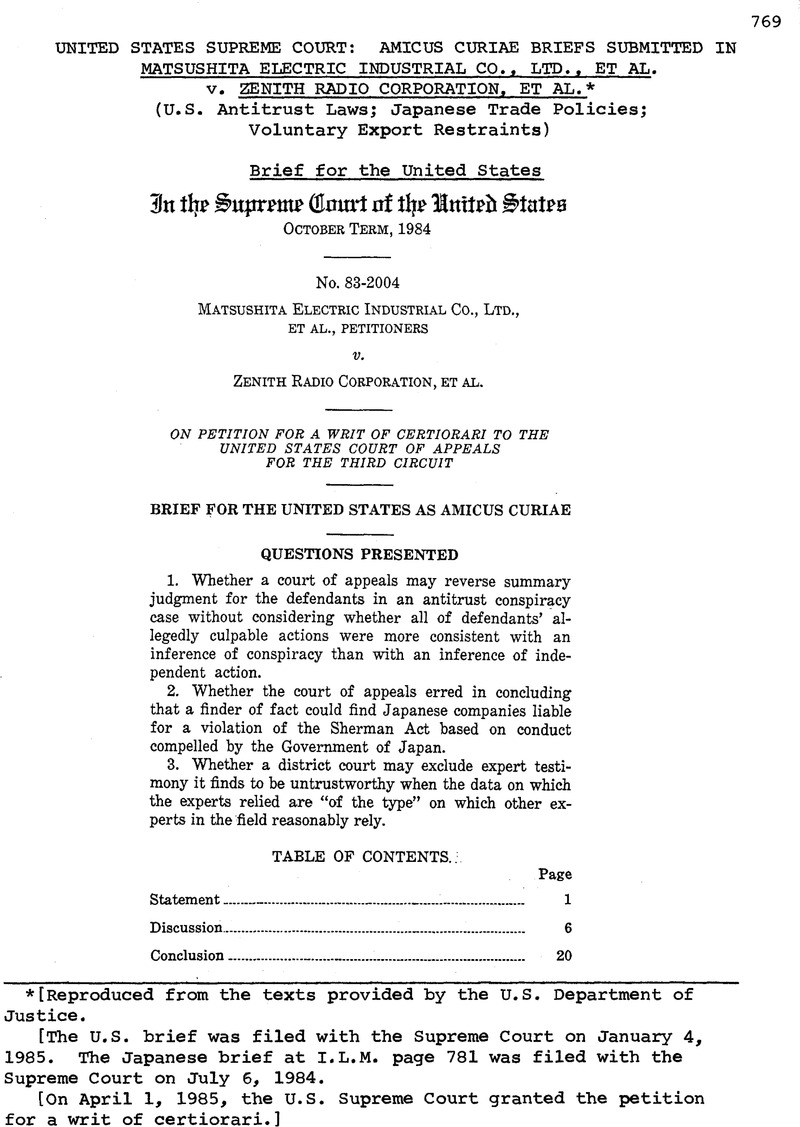

* [Reproduced from the texts provided by the U.S. Department of Justice.

[The U.S. brief was filed with the Supreme Court on January 4,1985. The Japanese brief at I.L.M. page 781 was filed with the Supreme Court on July 6, 1984.

[On April 1, 1985, the U.S. Supreme Court granted the petitionfor a writ of certiorari.]

1 Respondents also alleged that the purported conspiracy involvedthe sale of consumer electronic products other than television sets.However, the case has focused almost entirely on television sets.See Pet. App. 247a n.7.

2 Respondents' Final Pretrial Statement, which constituted theircomplete offer of proof on the antitrust claims, exceeded 17,000pages. See Pet. App. 268a.

3 In 1977 and 1978, at respondents' request, the Antitrust Divisionconducted a thorough examination of what respondents characterizedas the most probative evidence of the alleged conspiracy. Likethe district court, the Division found “no evidence of concertedpredatory conduct intended to destroy and supplant the U.S. colorTV industry, either at an earlier period of time or at the presenttime.” Pet. App. 23a (statement of Assistant Attorney GeneralJohn H. Shenefield).

4 The court of apgjlals affirmed the grant of summary judgmentin favor of defendants Motorola and Sears because there was noevidence that either company was aware of the resale price maintenanceconspiracy in Japan, the five-company rule, or the allegedconcerted action by the other defendants to evade the check priceagreements imposed by MITI (Pet. App. 176a, 180a-183a). Thecourt also affirmed summary judgment in favor of defendant Sonyon the grounds that Sony never gave rebates, never sold at dumpingprices, and occupied the high end of the price spectrum (id. at183a-185a).

5 None of the questions presented in the petition explicitlyaddresses the antidumping charges. However, petitioners statethat they challenge the antidumping decision insofar as it restson the same conspiracy evidence as the antitrust charges. Pet. 8.

6 We take no position on the third question raised by the petition, involving the admissibility of expert testimony.

7 Although the court of appeals held admissible much of theevidence the district court excluded, the two courts appear to haveconsidered essentially the same body of evidence, since the districtcourt was willing to assume the admissibility of much of respondents'evidence (see Pet. App. 253a-254a n.18). Even if the districtcourt failed to consider evidence the court of appeals held admissible,the court of appeals on remand could conclude that this washarmless error because application of the Cities Service standardto the admissible evidence leads to the conclusion that petitionerswere entitled to summary judgment in any event.The antitrust claims form the greater part of this litigationand present the more significant legal issues; moreover, guidancefrom this Court concerning the evaluation of evidence of the allegedantitrust conspiracy would assist on remand in dealing furtherwith the issue of specific intent in connection with the antidumpingclaims.

8 In Theatre Enterprises, Inc. v. Paramount Film Distributing Corp., 346 U.S. 537, 541-542 (1954), this Court rejected the contentionthat a conspiracy must be inferred where the plaintiffproved only parallel conduct and the defendants showed that theirbehavior was consistent with individual self interest. In casesin which this Court has approved inference of a conspiracy fromparallel behavior, that behavior was inconsistent with the hypothesisthat each defendant made an independent business decision to actas it did. See, e.g., American Tobacco Co. v. United States, 328U.S. 781, 800-808 (1946) ; Interstate Circuit, Inc. V. United States,306 U.S. 208, 222-225 (1939).

9 See Pet. App. 164a. Although the court of appeals did not mention Cities Service, it cited several Third Circuit decisions that applied the Cities Service principle.

10 For example, the court of appeals recognized that an agreementamong petitioners that fixed minimum prices for the UnitedStates market (i.e., the check price agreement) would tend to keepprices up and would “in isolation protect competitors like[respondents] from competition,” so that respondents could not,“absent other circumstances,” maintain this lawsuit “because theycould not show the requisite injury to their business or property.”Pet. App. 178a. In order to prove antitrust injury under theirtheory, respondents were required to prove that petitioners agreedto set predatory prices. See id. at 177a-179a.

11 We agree with the court of appeals that “direct evidence of some kinds of concert of action like price fixing in Japan may becircumstantial evidence of a broader conspiracy” (Pet. App. 165a).The issue here, however, is whether the existence of such evidencechanges the standard under which ambiguous evidence consistingof consciously parallel conduct is evaluated on motions forsummary judgment.

12 The court of appeals determined that petitioners were not entitled to summary judgment on respondents' Antidumping Act claims. See page 5, supra. We take no position on the correctness of that conclusion.

13 One commentator has concluded that such a theory makes no sense in the circumstances of this case. See Easterbrook, The Limits of Antitrust, 63 Tex. L. Rev. 1, 26-27 (1984) (“Thepredation-recoupment story [in this case] does not makesense, and we are left with the more plausible inference that theJapanese firms did not sell below cost in the first place. They wereiust engaged in hard conroetition.”).

14 Such considerations have led the courts of appeals to concludethat strong evidence of below-cost pricing is vital to a determinationthat a low-price strategy amounts to unlawful predation that violatesSection 2 of the Sherman Act. See, e.g., Southern Pacific Communications Co. V. American Telephone & Telegraph Co., 740F.2d 980, 1002-1007 (D.C. Cir. 1984); Adjusters Replace-A-Car. Inc. v. Agency Rent-A-Car, Inc., 735 F.2d 884, 888-891 (5th Cir.1984) ; Arthur S. Langenderfer, Inc. V. S.E. Johnson Co., 729 F.2d1050, 1056-1058 (6th Cir. 1984) ; William Inglis & Sons Baking Co. v. ITT Continental Baking Co., 668 F.2d 1014, 1031-1039 (9thCir. 1981), cert, denied, 459 U.S. 825 (1982); Northeastern Telephone Co. V. American Telephone & Telegraph Co., 651 F.2d 76, 86-88 (2d Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 455 U.S. 943 (1982). The FederalTrade Commission has reached a similar conclusion. See, e.g., International Telephone & Telegraph Co., 3 Trade Reg. Rep. (CCH)1f 22,188, at 23,081-23,085 (July 25, 1984) ; General Foods Corp., 3Trade Reg. Rep. (CCH) If 22,142, at 22,974-22,976 (Apr. 6, 1984).

15 Indeed, the court of appeals never considered whether respondentshad adduced any evidence that petitioners' prices were belowany measure of cost. Rather, the court merely summarily characterizedrespondents' evidence as indicating that petitioners sold“at prices below the prices at which [respondents] couldsuccessfully compete” and that “produced losses” for petitioners.Pet. App. 167a, 179a.The district court's opinions indicate that respondents' evidenceof “below cost” sales consisted solely of the testimony oftheir chief expert, Dr. DePodwin, that four petitioners sometimessold their products in the United States at prices below somemeasure of their costs. Pet. App. 473a, 1065a. Dr. DePodwin'stestimony, in turn, was “a mathematical construction” based ohcertain assumptions about petitioners' costs {ibid.). The districtcourt noted that “far more reliable evidence of [petitioners'] costswas available to [respondents] in discovery, but * * * they had notavailed themselves of it” {id. at 473a n.200; see id. at 1065a-1069a).

16 Respondents mistakenly suggest {e.g., Br. in Opp. 5, 22) thatif the Court grants review in this case it will be required to siftthrough the entire record. In fact, the Court would be requiredto decide only whether the court of appeals failed to apply the properlegal standard in evaluating the evidence of conspiracy. If theCourt should reverse on this point, it could remand the case tothe court of appeals for further proceedings consistent with theCourt's opinion.

17 In Continental Ore Co. v. Union Carbide & Carbon Corp.,antitrust defendants contended that the Canadian governmenthad compelled them to engage in the anticompetitive acts at issuethere. This Court concluded, however, that the defense was notavailable because there was “no indication that [any] official withinthe * * * Canadian Government approved or would have approvedof” the anticompetitive conduct, or that any Canadian law otherwisecompelled the conduct. 370 U.S. at 706-707. The Court hadno occasion to discuss a situation in which, as here, the recordincludes a statement by a foreign government that it has compelledsome or all of the allegedly anticompetitive conduct at issue.

I t appears that only one court has found that the facts of thecase before it would support a sovereign compulsion defense. SeeInteramerican Refining Corp. v. Texaco Maracaibo, Inc., supra.Other courts have concluded that the defendantjinvolved failed toprove that their conduct was compelled. See, e.g., Timberlane Lumber Co. v. Bank of America, 549 F.2d at 608; Linseman v.World Hockey Ass'n, 439 F. Supp. 1315, 1324 (D. Conn. 1977) ;United States v. Watchmakers of Switzerland Information Center, Inc., 1963 Trade Cas. (CCH) fi 70,600, at 77,456-77,457 (S.D.N.Y.1962).

18 The sovereign compulsion defense differs from the act ofstate doctrine, which “precludes the courts of this country frominquiring into the validity of the public acts a recognized foreignsovereign power committed within its own territory.” Banco National de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U.S. 398, 401 (1964). It differsalso from the state action doctrine applicable to domestic antitrustdisputes, which reflects the view that, while the Sherman Act'sproscription of anticompetitive conduct is the supreme law of theland, Congress generally did not intend by its silence in theSherman Act to prohibit action of a state that may restrain competition.See Parker V. Brown, 317 U.S. 341, 351 (1943).

19 Respondents contend (Br. in Opp. 22-23) that petitioners havenot preserved their argument concerning sovereign compulsion.However, the pleadings make it plain that petitioners did raise theargument in the court of appeals (see pages 37-44 & n.34 of the petitioners'brief filed in the court of appeals) and that respondentsdisputed it at length (see pages 79-88 of the respondents' replybrief filed in the court of appeals).

20 The court of appeals held that a fact-finder could concludethat the Government of Japan did not “determine” the minimumprice levels under the check price agreement and apparently rejectedpetitioners' sovereign compulsion defense on that basis. SeePet. App. 188a-189a. In so holding, the court erred in failing togive weight to the explanation in the MITI Statement that MITIexercised “direction and supervision concerning minimum pricesat which televisions could be sold for exportation to the UnitedStates * * * continuously from 1963 until February 28, 1973” (id.at 11a).

21 In conveying this explanation to the district court, the JapaneseGovernment properly sought to present its showing on the sovereigncompulsion issue directly to the court. This Court has approved aprocedure under which a foreign government may convey its viewsto the Court directly in cases in which it has an interest by thefiling of a brief as amicus curiae. See 73 Am. J. Intl L. 124 (1979).The State Department has encouraged foreign governments to communicatetheir views directly to United States courts. See ibid.; id. at 678-679.

The court of appeals nevertheless appears to have wholly disregardedthe MITI Statement in rejecting petitioners' foreign sovereigncompulsion defense. In declining to give weight to, or evento acknowledge, the MITI Statement, the court of appeals failed toaccord the proper respect due a foreign government that has takenappropriate steps to convey its views to a United States court inconnection with litigation.

22 The MITI Statement also explained that MITI had directedthe regulations of the Japan Machinery Exporters Association,which included the five-company rule. The court of appeals thereforeerred in concluding that there was “no record evidence” (Pet.App. 189a) suggesting that the five-company rule was compelledby the Japanese Government. The MITI Statement did not explicitlysingle out the five-company rule as an example of conductrequired by MITI. The Government of Japan recently transmitteda diplomatic Note Verbale that states unequivocally that the JapaneseGovernment did mandate the five-company rule. See Br. Ofthe Gov't of Japan 2a. However, the court of appeals did not havethe benefit of the Note Verbale.

23 We do not suggest that a court is precluded from consideringcompelled conduct for all purposes in an antitrust case. There arecircumstances in which it would be appropriate, e.g., to considerthe existence of compelled conduct as evidence that some otheralleged event has taken place. However, the court of appeals erredin relying on the compelled conduct in this case as a possible predicatefor liability, rather than merely as evidence of the existenceof some other fact.

24 For example, in establishing a government policy for the steelindustry, President Reagan recently directed the United StatesTrade Representative to “negotiate 'surge control’ arrangementsor understandings and, where appropriate, suspension agreementswith countries whose exports to the United States have increasedsignificantly in recent years due to an unfair surge in imports” andto “reaffirm existing measures with countries that have voluntarilyrestrained their exports to our market.” 49 Fed. Reg. 36813 (1984).

25 In imposing those controls, the Government of Japan may wellhave relied on the view that the defense of sovereign compulsionwould be available to Japanese automobile manufacturers that conformedtheir conduct to the controls. A letter dated May 7, 1981,from the Attorney General of the United States to the Ambassadorof Japan, advised the Government of Japan that the voluntaryrestraint arrangement involving- export of Japanese-built automobilesto the United States “would properly be viewed as having beencompelled by the Japanese government, acting within its sovereignpowers” and that, in the Justice Department's view, compliance ofJapanese automobile companies with the program “would not giverise to violations of United States antitrust laws” (Pet. App. 26a).We are advised by the United States Trade Representative thatextension of this arrangement, which has important implicationsfor this country's domestic economic and international trade policies,will be considered in the near future.

26 In addition to the Government of Japan (see Br. of the Gov'tof Japan la-4a), the Governments of Australia, Canada, France,the Republic of Korea, Spain, and the United Kingdom have formallyadvised the Department of State of their serious concern aboutthe potential adverse impact on their trade relations with theUnited States of the court of appeals' treatment of the sovereigncompulsion issue. We are lodging copies of the communicationsreceived by the State Department from these governments with theClerk of the Court and providing copies to counsel.1 “App.” refers to the Appendix attached to this brief.2 The Court may wish to request the views of the UnitedStates concerning the questions discussed in this brief amicuscuriae.