No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

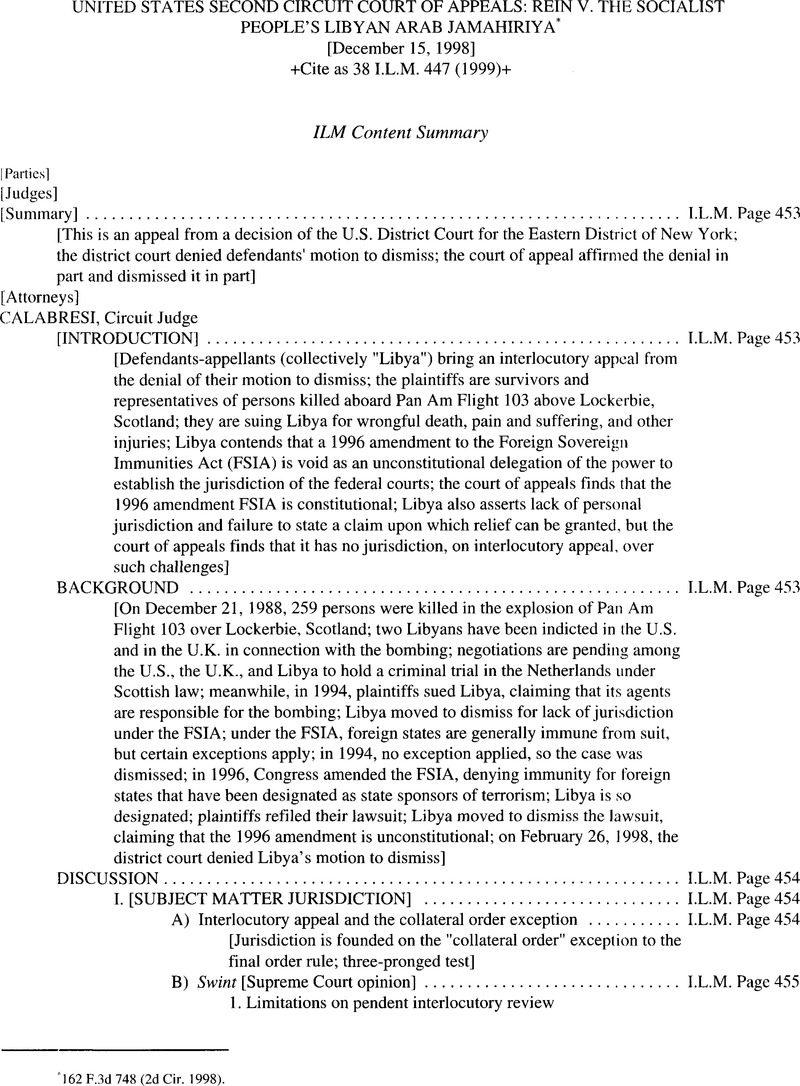

162F.3d748(2dCir. 1998).

[1] The Honorable Nicholas Tsoucalas, Judge of the United States Court of International Trade, sitting by designation.

[1] 28 U.S.C. § 1604 (1994), a provision of the FSIA, reads, in its entirety: “Subject to existing international agreements to which the United States is a party at the time of enactment of this Act a foreign state shall be immune from the jurisdiction of the courts of the United States and of the States except as provided in sections 1605 to 1607 of this chapter.“

[2] 28 U.S.C. § 1330(a) (1994), another provision of the FSIA, reads, in its entirety:“The district courts shall have original jurisdiction without regard to amount in controversy of any nonjury civil action against a foreign state as defined in section 1603(a) of this title as to any claim for relief in personam with respect to which the foreign state is not entitled to immunity either under sections 1605-1607 of this title or under any applicable international agreement.“Although this language could be read to mean that civil actions are divided into jury and nonjury actions, and that, under this section, the district courts have jurisdiction only in nonjury actions, we have in fact read it to mean (1) that the district courts have jurisdiction over civil actions against foreign states regardless of whether those actions, if brought against domestic defendants, would be jury or nonjury actions, and (2) that all such actions are to be tried without juries. See Bailey v. Grand Trunk Lines New England, 805 F.2d 1097, 1101 (2d Cir. 1986); Ruggiero v. Compania Peruana de Vapores “Inca Capac Yupanqui” 639 F.2d 872, 875-76 (2d Cir. 1981).

[3] 28 U.S.C. § 1605 (Supp. 1996), another provision of the FSIA, reads, in pertinent part:“(a) A foreign state shall not be immune from the jurisdiction of courts of the United States or of the States in any case- (7)… in which money damages are sought against a foreign state for personal injury or death that was caused by an act of torture, extrajudicial killing, aircraft sabotage, hostage taking, or the provision of material support or resources (as defined in section 2339A of title 18) for such an act if such act or provision of material support is engaged in by an official, employee, or agent of such foreign state while acting within the scope of his or her office, employment, or agency, except that the court shall decline to hear a claim under this paragraph - (A) if the foreign state was not designated as a state sponsor of terrorism under section 6(j) of the Export Administration Act of 1979 (50 U.S.C. App. 2405(j)) or section 620A of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (22 U.S.C. 2371) at the time the act occurred, unless later so designated as a result of such act[.]“

[4] The reason why denials of qualified immunity are generally appealed immediately is analogous to the reason why interlocutory review is available for denial of sovereign immunity. Qualified immunity, like sovereign immunity, is an immunity from litigation and not just from liability. See Mitchell v. Forsyth, All U.S.511, 526 (1985).

[5] The Court in Swint discussed several prior cases in which courts had faced the issue of pendent jurisdiction on interlocutory appeal, and, in doing so, it did not differentiate between cases involving pendent issues and those involving pendent parties. An example is Abney v. United States, 431 U.S. 651 (1977).The petitioner in Abney was a criminal defendant who was authorized under the collateral order doctrine to bring an interlocutory appeal of the denial of his motion to dismiss an indictment on double jeopardy grounds. He also sought to raise another issue, challenging the sufficiency of the indictment. The Supreme Court held that the Court of Appeals lacked authority to review the latter claim on interlocutory appeal. See id., 431 U.S. at 662-63. Swint presented Abney as an illustration of the proper approach to questions of pendent jurisdiction on interlocutory appeal. See Swint, 514 U.S. at 49. But the motion challenging the sufficiency of the indictment and the motion alleging double jeopardy were both raised by the same party: the defendant. Thus, the rule of Swint seems not to be limited to the pendency of parties. It applies as well to the pendency of issues.

[6] Thus, we have held that the question of whether a public official defending against a civil suit is entitled to qualified immunity is inextricably intertwined with a determination of what the plaintiffs clearly established rights were. See McEvoy v. Spencer, 124 F.3d 92, 96 (2d Cir. 1997); Kaluczky v. City of White Plains, 57 F.3d 202, 207 (2d Cir. 1995).

[7] Earlier in the litigation, there had also been a challenge to personal jurisdiction on the grounds that service of process had been insufficient, but that issue disappeared after the district court allowed the plaintiff extra time to perfect its service. See Hanil Bank, 148 F.3d at 130.

[8] The Supreme Court has declined to hold that the “direct effects” requirement of the commercial activities exception incorporates the “minimum contacts” test. See Republic of Argentina v. Weltover, Inc., 504 U.S. 607, 619 (1992). (It has also declined to hold the contrary. See id.) It is thus possible that a foreign sovereign could be subject to subject matter jurisdiction under the commercial activities exception without being within the personal jurisdiction of an American court. But Hanil Bank did not present that scenario. The findings that underlay subject matter jurisdiction in Hanil Bank involved purposeful availment and hence minimum contacts. See Hanil Bank, 148 F.3d at 130, 132; see also Weltover, 504 U.S at 619-20 (foreign sovereign that issued debt instruments payable in U.S. currency, payable in New York, and appointed agent for transaction in New York had “purposefully availed itself of the privilege of conducting activities within the United States” (internal quotation marks and brackets omitted)).

[9] At oral argument, Libya in effect conceded as much.

[10] This remains so even if it turns out, on appeal, that the party was not subject to jurisdiction. See Van Cauwenberghe, 486 U.S. at 526. And it makes no difference whether the jurisdiction to which the party is not subject is personal jurisdiction or jurisdiction over the subject matter. As long as a defendant is not entitled to immunity, and therefore privileged against litigation itself, it suffers no legal wrong by the mere fact of suit. As a result, any lack of jurisdiction may be adequately addressed on appeal from a final order. See id.

[11] That would not be so if the argument that the plaintiffs failed to state a claim asserted that a necessary ground for deprivation of immunity under the FSIA were lacking. Thus, if a foreign sovereign were sued for an airline crash on a negligence theory, rather than on a theory of sabotage, the defendant could assert that even if everything in the complaint were taken as true, there would be no jurisdiction, because § 1605(a)(7) removes sovereign immunity only for claims arising out of aircraft sabotage and not for air disasters generally. In such circumstances, a defendant's motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim might well be inextricably intertwined with the issue of sovereign immunity and hence jurisdiction. Whether the question of immunity would then be sufficiently independent of the merits to meet the second prong of Cohen need not be considered today.

[12] The district court also appeared to suggest that § 1605(a)(7) delegated no more than advisory authority on jurisdiction, leaving the courts with discretion to entertain or ignore a defense of sovereign immunity in the case of countries designated as state sponsors of terrorism. See Rein, 995 F. Supp. at 329. This approach, however, misreads the statute, which provides that countries so designated “shall not be immune from the jurisdiction of courts of the United States” in cases arising from aircraft sabotage or the other circumstances there identified. 28 U.S.C. § 1605(a)(7) (emphasis added). The language of the statute leaves no room for a court to exercise discretion in the way envisioned by the district court.

[13] This position is consistent with the Court's recent jurisprudence of sovereign immunity in another context: that of suits against states in federal courts. See Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Florida, 517 U.S. 44 (1996) (holding that the sovereign immunity of states is a jurisdictional issue, not an affirmative defense).

[14] The district court also made another attempt to construe the FSIA in a way that would prevent § 1605(a)(7) from involving the power to determine jurisdiction: it maintained that the FSIA is actually not a jurisdiction-setting statute at all. Jurisdiction over suits against foreign sovereigns, the district court stated, is conferred on the federal courts by Article III of the Constitution, and the FSIA merely confirms that jurisdiction. Rein, 995 F. Supp. at 328-29. If that were the case, and the FSIA were not a jurisdictional statute, then delegating the power to determine the scope of the FSIA would not affect the bounds of federal jurisdiction. But it is well established that the FSIA is the source of jurisdiction over actions against foreign states, just as 28 U.S.C. § 1331 is the source of jurisdiction over federal question cases and 28 U.S.C. § 1332 is the source of jurisdiction over diversity claims. See Ruggiero, 639 F.2d at 876. Accordingly, the power to determine the applicability of the FSIA can indeed be the power to set the jurisdiction of the federal courts.