No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

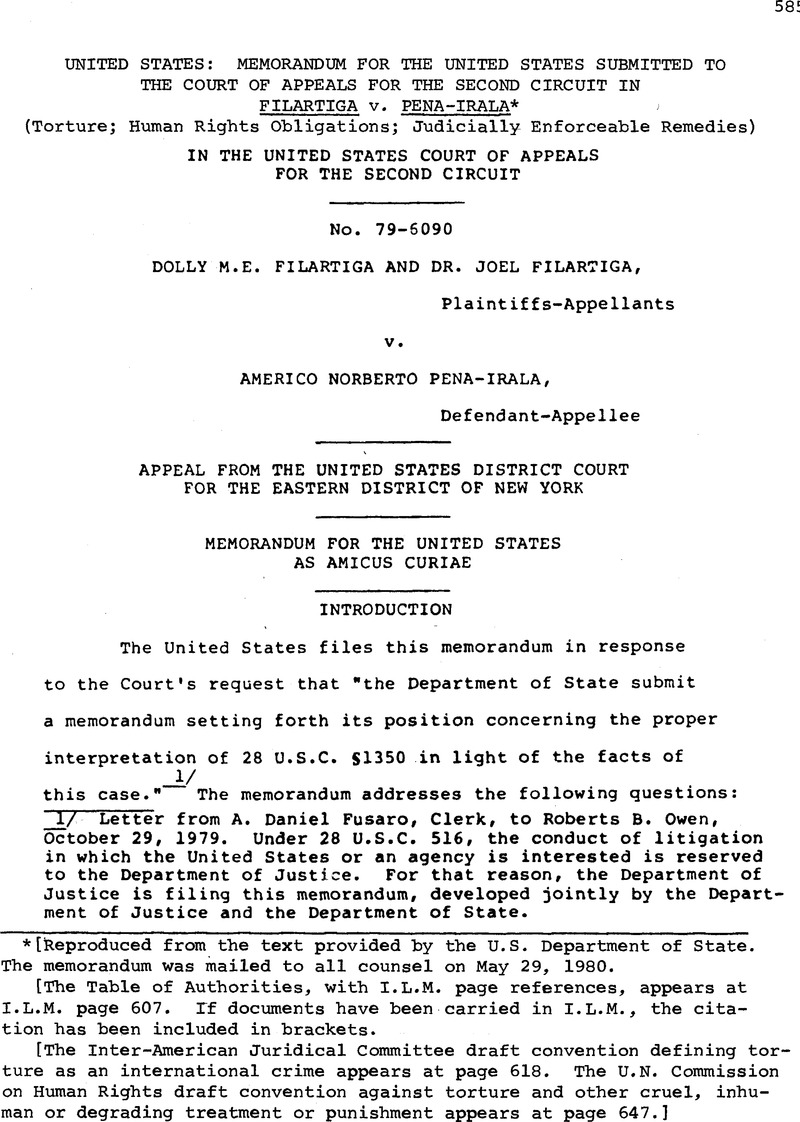

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Department of State. The memorandum was mailed to all counsel on May 29, 1980.

[The Table of Authorities, with I.L.M. page references, appears at I.L.M. page 607. If documents have been carried in I.L.M., the citation has been included in brackets.

[The Inter-American Juridical Committee draft convention defining torture as an international crime appears at page 618. The U.N. Commission on Human Rights draft conventionagainst torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment appears at page 647.]

1/ Letter from A. Daniel Fusaro, Clerk, to Roberts B. Owen, October 29, 1979. Under 28 U.S.C. 516, the conduct of litigation in which the United States or an agency is interested is reserved to the Department of Justice. For that reason, the Department of Justice is filing this memorandum, developed jointly by the Department of Justice and the Department of State.

2/ “AT” references are to the joint appendix.

3/ Maritime law has evolved significantly since 1789. See Moragne v. State Marine Lines, 398 U.S. 375 (1970) (overruling an 1886 decision and holding that maritime law affords a remedy for wrongful death on navigable waters).

4/ E.g. , Oppenheim, L. International Law; A Treatise, Vol. 1, 362-369 (2d Ed. 1912)Google Scholar.

5/ Statute of the International Court of Justice, Article 38, June 26, 1945, 59 Stat. 1055, 1060 (effective October 24, 1945). See also, The Paquete Habana, supra, 175 U.S. at 700.

6/ The Covenant of the League of Nations, Articles 22, 23, June 28, 1919, reprinted in Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States of America 1776-1949, 2 Bevans 48, 5S-57U969).

7/ See, e.g., Treaty Between the Principal Allied and Associated Powers and Poland, signed at Versailles, June 28, 1919, reprinted in Treaties, Conventions, International Acts, Protocol and Agreements Between the United States of America and Other Powers 1910-1923, 3 Malloy-Redmond 3714 (1923). In addition, the general treaties of peace concluding the war included provisions aimed at guaranteeing minority rights. See, e.g., Treaty of Peace with Austria, Part 3, Sec. 5, signed at St. Germaine-en-Laye, September 10, 1919, reprinted in 3 Malloy-Redmond 3149.

8/ United Nations Charter, June 26, 1945, Arts. 55, 56, 59 Stat. 1031, 1045-1046, 3 Bevans 1153, 1166-1167 (1969).

9/ Charter of the Organization of American States, Articles 3(j), 16, 43(a) (entered into force December 13, 1951), as amended by the Protocol of Buenos Aires of 1967 (entered into force Feburary 27, 1970), OAS Treaty Series No. 1-C, OAS, OR, OEA/Ser.A/2 (English), Rev. (1970), 21 U.S.T. 607, T.I.A.S. 6847.See also American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, ch. 1 (1948), OAS, OR, OEA/Ser. L/V/E.23, Doc. 21, Rev. 2.

10/ General Assembly Resolution 2200 (XXI)A (December 16, 1966), entered into force March 23, 1976; Four Treaties Pertaining to Human Rights, Message from the President of the United States, S. Doc. No. Exec. C, D, E, and F, 95th Cong., 2d Sess. (197.8).

11/ Signed at San Jose, Costa Rica, November 22, 1969, entered into force July 18, 1978, OAS Treaty Series No. 36, OAS, OR,OEA/Ser.A/16(English).

12/ Signed November 4, 1950, entered into force September 3, 1953, Council of Europe, European Treaty Series No. 5 (1968), 213 U.N.T.S. 221.

13/ General Assembly Resolution 217 (III)A (December 10, 1948).

14/ See Addendum.

15/ See United Nations Action in the Field of Human Rights (1974), ST/HR/2 (Pub. Sales No. E.74.XIV.2), at 14-15.

16/ CQnference on Security and Cooperation in Europe; Final Act (Helsinki, 1975), 73 Dep't State Bull. 323, 325 (1975).

17/ As further evidence, see Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation among States in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, General Assembly Resolution 2625(XXV) (October 24, 1970). The Declaration proclaims that:

Every State has the duty to promote through joint and separate action universal respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms in accordance with the Charter.

It further states:

The principles of the Charter which are embodied in this Declaration constitute basic principles of international law ***.

18/ United Nations Action in the Field of Human Rights, supra, at 17-18.

19/ United Nations Action in the Field of Human Rights, supra, at 19.

20/ Nuclear Tests (Australia v. France), Judgment of December 20, 1974, [1974] I.C.J. 253, 303 (Opinion of Judge Petrer.. ; Advisory Opinion on Legal Consequences for States of the Continued Presence of South Africa in Namibia (South West Africa) Notwithstanding Security Council Resolution 276 (1970), [1971] I.C.J. 16.

21/ See Affidavit of Richard B. Lillich (A. 65-70); Affidavit of Thomas M. Franck (A. 63-64); Affidavit of Myres S. MacDougal (A. 71); Affidavit of Richard Anderson Falk (A. 61-62).

22/ Department of State, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 1979, published as Joint Committee Print, House Conun. on Foreign Affairs & Senate Comm. on Foreign Relations, 96th Cong., 2d Sess. (February 4, 1980) Introduction at 1.

23/ Dreyfus mistakenly relied on Mr. Justice White's dissent in Sabbatmo for its conclusion. At one point in his opinion Mr. Justice White does distinguish several cases decided long before the turn of the century as cases where violations of international law were not present because the parties were nationals of the acting state. 376 U.S. at 442, n. 2. However, Mr. Justice White makes clear elsewhere in his opinion that this is not the law today. In discussing a case in which an individual brought suit to recover property expropriated by the Nazis, Mr. Justice White specifically explained that “racial and religious expropriations, while involving nationals of the foreign state and therefore customarily not cognizable under international law, had been condemned in multinational agreements and declarations as crimes against humanity.” Id. at 457 n. 18. Accordingly, Mr. Justice White concludedT “the acts could *** be measured in local courts against widely held principle rather than judged by the parochial views of the forum.” Ibid. Mr. Justice White's opinion thus reinforces our view that international law prohibits a nation from violating the fundamental human rights of its citizens.

24/ Article 5 provides in relevant part, that—“No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman, or degrading punishment or treatment.” OAS Treaty Series No. 36, supra, at 2.

25/ Article 7: “No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” General Assembly Resolution 2200 (XXI)A, supra.

26/ Article 3: “No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” Council of Europe, European Treaty Series No. 5 (1968), 213 U.N.T.S. 221.

27/ Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War of August 12, 1949, 6 U.S.T. 3316, T.I.A.S. No. 3364, Articles 3, 13, 129, 130.

28/ These treaty provisions, in conjunction with other evidence, are persuasive of the existence of an international norm that is binding as a matter of customary law on all nations, not merely those that are parties to the treaties. A, D’Amato, The Concept of Custom in International Law 103, 124-128 1971).

The United States has signed both the American Convention on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and those instruments await the advice and consent of the Senate. See Four Treaties Pertaining to Human Rights, supra. Only European countries are entitled to be parties to the third treaty.

29/ For instance, Article 20 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights prohibits “advocacy of national, racial, or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence ***.” Four Treaties Pertaining to Human Rights, supra, at 29. This provision conflicts with principles of free speech that are central to the political values of many democracies. A number of nations, including the United Kingdom, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Finland, expressed reservations to Article 20 upon ratifying the Covenant. Multilateral Treaties in Respect of Which the Secretary General Performs Depository Functions, UN Doc. ST/LEG/Ser. D/12 108, 112, 114 (1978). President Carter has proposed a similar reservation in connection with United States ratification. Four Treaties Pertaining to Human Rights, supra, at XI-XII.

30/ International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, Articles 7, 9. Four Treaties Pertaining to Human Rights, supra, at 15-16.

31/ Four Treaties Pertaining to Human Rights, supra, at X.

32/ Id.at IX.

33/ International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, Article 2(1), Four Treaties Pertaining to Human Rights, supra, at 14.

34/ See, e.g., Affidavit of Richard Anderson Falk (A. 62); Affidavit of; Thomas M. Franck (A. 64). In exchanges between United States embassies and all foreign states with which the United States maintains relations, it has been the Department of State's general experience that no government has asserted a right to torture its own nationals. Where reports of such torture elicit some credence, a state usually responds by denial or, less frequently, by asserting that the conduct was unauthorized or constituted rough treatment short of torture. The Department's Country Reports on Human Rights, supra, reports no assertion by any nation that torture is justified.

35/ General Assembly Resolution 217(III)A (December 10, 1948), Art. 5.

36/ General Assembly Resolution 3452(XXX) (December 9, 1975). Article 2 of the Declaration provides:

Any act of torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment is anoffence to human dignity and shall be condemned as a denial of the purposes of the Charter of the United Nations and as a violation of the human rights and fundamental freedomsproclaimed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Article 3 provides:

No State may permit or tolerate torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Exceptional circumstances such as a state of war or a threat of war, internal political instability or any other public emergency may not be invoked as a justification of torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

37/ General Assembly Resolution 3452 (XXX) (December 9, 1975), Annex, Art. 1 (1). The United Nations Human Rights Commission is now drafting a Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. That draft Convention would require each party to make torture criminally punishable within its jurisdiction. It contains a very similar definition of torture (E/CN.4/1367, Annex at 1):

For the purpose of this Convention, torture means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.

38/ 48 Revue Internationale de Droit Penal Nos. 3 and 4, at 208 (1977) Paraquay is one such nation.

39/ Id. at 208-209.

40/ Id. at 211.

41/ 22 U.S.C. 2304(a)(2), (d); 22 U.S.C. 2151.

42/ Affidavit of Richard Anderson Falk (A. 61-62); Affidavit of Thomas M. Franck (A. 63-64); Affidavit of Richard B. Lillich (A. 65-70); Affidavit of Myres S. MacDougal (A. 71).

43/ O’Boyle, Torture and Emergency Powers Under the European Convention on Human Rights: Irelan Rightc: Ireland v. The United Kingdom, 71 Am.J. Int'l L. 674, 687-688 (1977).

44/ In Matter of the Republic of the Philippines, 46 BVerfGE 342, 362 (2 BvM 1/76, December 13, 1977) translated from the German by Stefan A. Riesenfeld); see also Borovsky v. Commissioner of Immigration, Judgment of September 28, 1951 (S.Ct. Philippines), summarized in [1951] United Nations Yearbook on Human Rights 287-288; Chirskoff v. Commissioner of Immigration, Judgment of October 26,1951 (S.Ct. Philippines), summarized in id. at 288-289; Judgment of Court of First Instance of Courtrai (Belgium) of June 10, 1954, summarized in [1954] United Nations Yearbookon Human Rights 21 (courts relied on Universal Declaration of Human Rights in ordering release from detention).

45/ There are few decisions which base judgments against torturers dTrectly on customary international law. But this attests to the longstanding condemnation of torture under municipal law and the more recent evolution of ternational human rights law. Courts have, nonetheless, invoked customary international law along with municipal and treaty law in cases involving torture.Ireland v. United Kingdom, Judgment of January 18, 1978 (European Ct. of Human Rights) summarized in [1978] Y.B. Eur. Conv. on Human Rights 602 (Council of Europe) (UN Declaration of Torture relied on in interpreting the European Convention of Human Rights);Auditeur Militaire v. Krumkamp, Pasicrisie Beige, 1950.3.37 (February 8, 1950) (Belgian Counseil de guerre de Brabant), summarized in 46 Am.J. Int'l L. 162-163 (1952) (Article 5 of Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which prohibits torture and cruel treatment, cited as authority that under customary international law the defendant accused of war crimes was not free to use torture).

46/ Article 45 of the Paraguayan Constitution.

47/ A. 51-53, 80.

48/ Because the lower court dismissed for lack of jurisdiction, it did not decide whether the case should be dismissed on the groundof forum non conveniens. Although we agree with plaintiffs that this question should be addressed by the district court first, we note that when the parties and the conduct alleged in the complaint have as little contact with the United States as they have here, abstention is generally appropriate. Romero v. International Terminal Operating Co., 358 U.S. 354 (1959); Lauritzen v. Larsen, 345 U.S. 571 (1953). Plaintiffs assert that abstention is inappropriate because a tort suit in Paraguay would be a sham. For reasons of comity among nations, however, such an assertion should not be accepted absent a very clear and persuasive showing. In determining whether abstention is appropriate, the court should also consider the fact that the defendant has been deported. Compare United States v. Castillo, 615 F.2d 878, 882 (9th Cir. 1980).

49/ Defendant erroneously suggests (Br. 4-16) that Section 1350 Is” unconstitutional in conferring jurisdiction on federal courts to entertain tort actions under the law of nations. Customary international law is federal law, to be enunciated authoritatively by the federal courts. Sabbatino, supra, 376 U.S. at 425; see The Paquete Habana, supra, 175 U.S. at 700. An action for tort under international law is therefore a case “arising under *** the laws of the United States” within Article III of the Constitution. See Note, Federal Common Law and Article III: A Jurisdictional Approach to Erie, 74 Yale L.J. 325, 331-336 (1964).