Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

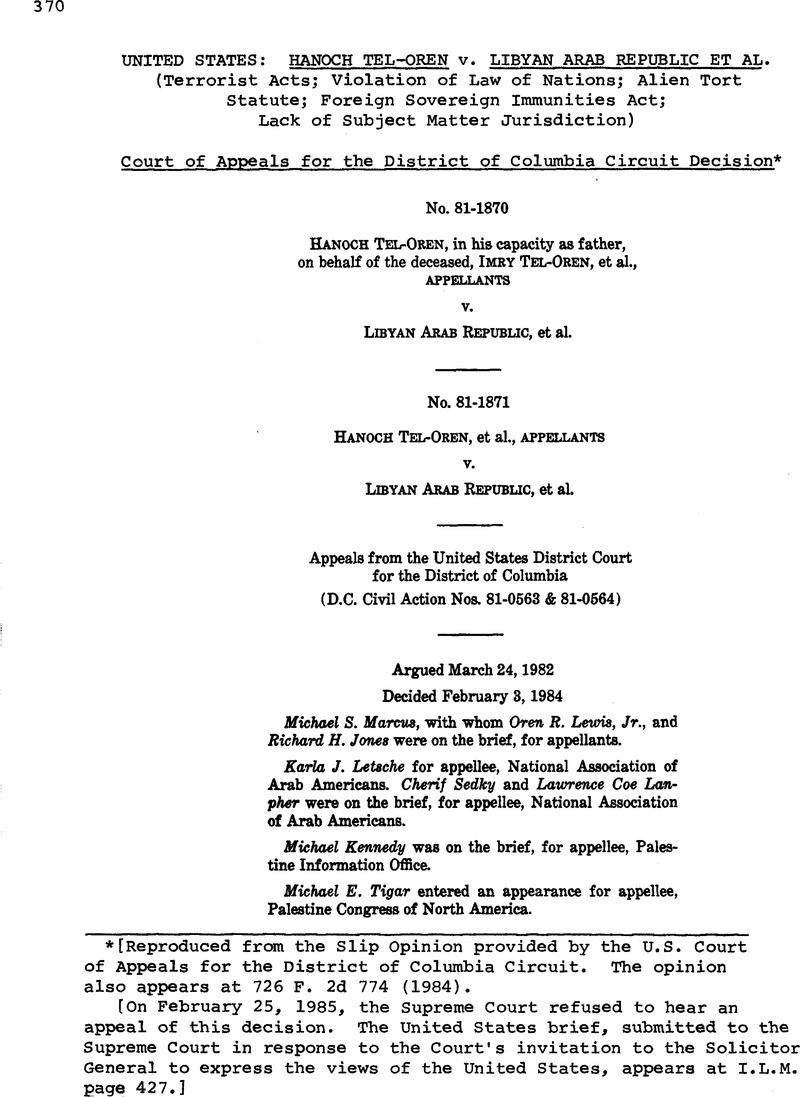

* [Reproduced from the Slip Opinion provided by the U.S. Courtof Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. The opinionalso appears at 726 F. 2d 774 (1984).

[On February 25, 1985, the Supreme Court refused to hear anappeal of this decision. The United States brief, submitted to theSupreme Court in response to the Court's invitation to the SolicitorGeneral to express the views of the United States, appears at I.L.M.page 427.]

1 That I confine my remarks to issues directly related tothe construction of § 1350 should in no respect be read as anendorsement of other aspects of my colleagues' opinions. Indeed,I disagree with much of the peripheral discussion they contain.

1 Plaintiffs do not pursue their claim against the Palestine Congress of North America on appeal.

2 [See I.L.M. pages 396 and 422.]

3 In obvious contrast is a treaty, which may create judicially enforceable obligations when that is the will of the parties toit. See People of Saipan v. Department of Interior, 502 F.2d90, 97 (9th Cir. 1974) (elaborating criteria to be used to determinewhether international agreement establishes affirmativeand judicially enforceable obligations without implementinglegislation), cert, denied, 420 U.S. 1003 (1975). Unlikethe law of nations, which enables each state to make an independentjudgment as to the extent and method of enforcinginternationally recognized norms, treaties establish both obligationsand the extent to which they shall be enforceable.8 It might be argued that in 1789 Congress had not enactedgeneral federal question jurisdiction, with its “arising under”provision, and could not have used that phraseology as areference point. Not until 1875 did Congress give federalcourts general original jurisdiction over federal question cases.Act of Mar. 3, 1875, ch. 137, § 1, 18 Stat. 470. However, in itsoriginal form, the predecessor to § 1350 did not contain theword “committed.” The pertinent part of the clause grantedjurisdiction “where an alien sues for a tort only in violationof the law of nations.” The word “committed” appears in a1948 recodification of the Judicial Code, Act of June 25, 1948,ch. 646, § 1350, 62 Stat. 869, 934, but was absent in earlierrecodifications. See, e.g., Act of Mar. 3, 1911, ch. 231, § 24,par. 17, 36 Stat. 1087,1093. By 1948 the term “arising under”was a well-established element of federal question jurisdiction, see American WeU Works Co. v. Layne & Bowler Co., 241 U.S.257, 260 (1916) (a suit “arises under” the law that createsthe action), and would have been the obvious choice of wordinghad Congress wished to make explicit that, in order to invoke§ 1350, a right to sue must be found in the law of nations.

4 I disagree both with Judge Bork and with plaintiffs inthis action that for purposes of the issues raised in this case,the jurisdictional requirements of § 1331 and § 1350 are thesame

5 The Second Circuit read § 1350 “not as granting new rightsto aliens, but simply as opening the federal courts for adjudicationof the rights already recognized by international law.” Filartiga, 630 F.2d at 887. I construe this phrase to meanthat aliens granted substantive rights under internationallaw may assert them under § 1350. This conclusion as to themeaning of this crucial yet obscure phrase results in partfrom the noticeable absence of any discussion in Filartiga onthe question whether international law granted a right ofaction.

6 While opinions of the Attorney General of course are notbinding, they are entitled to some deference, especially wherejudicial decisions construing a statute are lacking. See, e.g., Oloteo v. INS, 643 F.2d 679, 683 (9th Cir. 1981) (opiniondeserves some deference); Montana Wilderness Ass’n v. United States Forest Serv., 496 F. Supp. 880, 884 (D. Mont 1980) (opinions are given great weight although not binding), aff'd I ndeed, a 1907 opinion of the United States AttorneyGeneral suggests just the opposite. It asserts that section1350 provides both a right to sue and a forum. Respondingto an inquiry about the remedies available to Mexicanon two paths, depending on whether the plaintiff is a citizen or an alien.

7 Indeed, international law itself imposes limits on the extraterritorialjurisdiction that a domestic court may exercise.It generally recognizes five theories of jurisdiction, the objectiveterritorial, national, passive, protective and universal.See RESTATEMENT OF THE LAW OF FOBEIGN RELATIONS (REVISED)§ 402 (Tent Draft No. 2,1981); see also United States v. James-Robinson, 515 F. Supp. 1340, 1344 n.6 (S.D. Fla.1981). The premise of universal jurisdiction is that a state“may exercise jurisdiction to define and punish certain offensesrecognized by the community of nations as of universalconcern,” RESTATEMENT OF THE LAW OF FOREIGN RELATIONS(REVISED) , supra, § 404, even w here no other recognized basisof jurisdiction is present.

8 One § 1350 case, discussed at length, infra, has adoptedthis framework, see Adra v. Clift, 195 F. Supp. 857 (D. Md.1961), and one law review note has endorsed the approach. See Note, A Legal Lohengrin: Federal Jurisdiction Under the Alien Tort Claims Act of 1789, 14 U.S.F.L. REV. 105, 123(1979).

9 Despite confusion in an early case, Mason v. The Ship Blaireau, 6 U.S. (2 Cranch) 240, 264 (1804), by 1809 it wasclear that the Constitution bars extending diversity jurisdictionto suits between aliens. See Hodgson & Thompson v. Bowerbank, 9 U.S. (5 Cranch) 303 (1809).

10 It might also be argued that § 1350 addressed actions fortortious violations only of the law of nations, not domesticlaw, and that the 1789 Act's grant of diversity jurisdictioncovered domestic torts only. However, when the 1789 JudiciaryAct was drafted, lawyers had no doubt that the lawof nations was a part of the common law encompassed by thediversity jurisdiction statute. See Dickinson, The Law of Nations as Part of the National Law of the United States (pt. l), 101 U. PA. L. REV. 26, 27 (1952); 4 BLACKS-TONE’SCOMMENTARIES 66-67 (Welsby ed. 1854); see also Respublica v. De Longchamps, 1 U.S. (1 Dall.) I l l , 116-17 (1784) (commonlaw criminal prosecution for violation of law of nations); ef. Warren, New Light on the History of the Federal Judiciary Act of 1789, 37 HARV. L. REV. 49, 73 (1923) (arguing thatfederal courts were intended to assert both statutory and commonlaw criminal jurisdiction, including over law of nationsoffenses). Section 1350 therefore offered to aliens who couldmeet the diversity jurisdiction criteria, and therefore bringan action in the circuit court, an alternative forum, undersome circumstances. For aliens unable to meet those criteria,§ 1350 opened the district courts for assertion of their claims.

11 Brierly enumerates “corruption, threats, unwarrantabledelay, flagrant abuse of judicial procedure, a judgment dictatedby the executive, or so manifestly unjust that no courtwhich was both competent and honest could have given it” asinstances of a denial of justice. J. BRIERLY, THE LAW OPNATIONS 287 (6th ed. 1963).

12 Similarly, at the Virginia Convention James Madisonsaid, “We well know, sir, that foreigners cannot get justicedone them in these courts, and this has prevented manywealthy gentlemen from trading or residing among us.” 3ELLIOT’S DEBATES 583 (1888). See also P. BATOR, P. MISHKIN,D. SHAPIRO & M. WECHSLER, HART AND WECHSLER’STHE FEDERAL COURTS AND THE FEDERAL SYSTEM 17 (2d ed.1973) (concluding that “the need for a grant [of federaljudicial power] going beyond cases involving treaties andforeign representatives seems to have been undisputed“). But see Warren, supra note 10, at 56 & n.19 (1923) (amongthe proposed amendments to the Constitution was “the eliminationof all jurisdiction based on diverse citizenship andstatus as a foreigner“).

13 This formulation of § 1350's underlying intent casts doubton the appropriateness of federal jurisdiction over suits betweentwo aliens. The United States might be less concernedabout the appearance of condoning a wrongful act if its owncitizen were not the perpetrator, because the state of thewrong-doer should provide the forum for relief, or sufferthe consequences. However, let us assume a tort is committedby an alien against an alien of different nationality, and theinjured alien sues the offender under a state's tort law. Nodiversity jurisdiction exists. See Hodgson & Thompson v. Bowerbank, 9 U.S. (5 Cranch) 303 (1809). A denial ofjustice might create the perception that the United States issiding with one party, thereby affronting the state of the other.While the potential for retribution is not direct, it would seemto be present, particularly when the tort occurs on UnitedStates soil.

14 Act of Mar. 8,1875, ch. 137, § 1,18 Stat. 470.

15 In the First Judiciary Act, district courts were grantedoriginal jurisdiction over a mixture of actions. The completeauthorization was as follows:Sec. 9. And be it further enacted, That the districtcourts shall have, exclusively of the courts of the severalStates, cognizance of all crimes and offences that shall becognizable under the authority of the United States, committedwithin their respective districts, or upon the highseas; where no other punishment than whipping, notexceeding thirty stripes, a fine not exceeding one hundreddollars, or a term of imprisonment not exceeding sixmonths, is to be inflicted; and shall also have exclusiveoriginal cognizance of all civil causes of admiralty andmaritime jurisdiction, including all seizures under lawsof impost, navigation or trade of the United States, wherethe seizures are made, on waters which are navigablefrom the sea by vessels of ten or more tons burthen, withintheir respective districts as well as upon the high seas;saving to suitors, in all cases, the right of a common lawremedy, where the common law is competent to give it;and shall also have exclusive original cognizance for allseizures on land, or other waters than as aforesaid, made,and of all suits for penalties and forfeitures incurred,under the laws of the United States. And shall also have cognizance, concurrent with the courts of the several States, or the circuit courts, as the case may be, of all causes where an alien sues for a tort only in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States. Andshall also have cognizance, concurrent as last mentioned,of all suits at common law where the United States sue,and the matter in dispute amounts, exclusive of costs, tothe sum or value of one hundred dollars. And shall alsohave jurisdiction exclusively of the courts of the severalStates, of all suits against consuls or vice-consuls exceptfor offences above the description aforesaid. And the aliens.The section 9 reference to concurrent jurisdictionwith the circuit courts therefore might reasonablyhave referred to actions by an alien “at common lawor in equity,” for a tort, involving more than five hundreddollars—in other words, to domestic torts cognitrialof issues in fact, in the district courts, in all causesexcept civil causes of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction,shall be by jury.

1 Stat 73, 76-77 (footnotes omitted) (emphasis added).

17 To be sure, the parallel is not perfect, since district courtscould hear actions for any amount in controversy if they metthe former § 1350's requirements.

18 As noted earlier, I have some misgivings about the proprietyof § 1350 actions between two aliens under this formulation. See note 13, supra.

19 Because even under this approach the Hanoch plaintiffsdo not allege a law of nations violation, it is unnecessary toconsider Article III implications of the formulation. It wouldappear, however, that there are no serious Article III problemsassociated with the Adra-type application of § 1350.

20 On the basis of international covenants, agreements anddeclarations, commentators have identified at least four actsthat are now subject to unequivocal international condemnation:torture, summary execution, genocide and slavery. SeeBlum & Steinhardt, Federal Jurisdiction over International Human Rights Claims: The Alien Tort Claims Act afterFilartiga v. Pena-Irala, 22 HARV. INT’L L.J. 53, 90 (1981); see also P. SIBGHART, THE INTERNATIONAL LAW OF HUMANRIGHTS 48 (1983) (cataloguing as recognized internationalcrimes certain war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide,apartheid and, increasingly, torture). Plaintiffs in this actionallege both torture and murder that amounts to summaryexecution. Filartiga accepted the view that official torture infact amounts to a law of nations violation. Analysis alongthe same lines would likely yield the conclusion that statesponsoredsummary executions are violations as well. However,by definition, summary execution is “murder conductedin uniform,” as opposed to lawful, state-imposed violence,Blum & Steinhardt, supra, at 95, and would be inapplicablehere. See id. at 95-96. Therefore, for purposes of this concurrence,I focus on torture and assume, arguendo, that tortureamounts to a violation of the law of nations when perpetratedby a state officer. I consider only whether non-state actorsmay be held to the same behavioral norms as states.

21 Our courts have in the past looked to the foreign policy ofthis nation, in particular to the recognition or non-recognitionof a foreign government, to determine the applicability of agiven legal doctrine. For example, in Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U.S. 398 (1964), the Supreme Court explicitlytied the application of the Act of State Doctrine to whetherthe foreign state was recognized by the United States. See376 U.S. at 401, 428. See also Oetjen v. Central Leather Co.,246 U.S. 297 (1918) (Supreme Court takes judicial noticeof Washington's recognition of Mexican government, appliesAct of State Doctrine retroactively to pre-recognition incidents). Indeed, the Court has made clear that the judiciaryis not to second guess the determination of the other branchesas to “[w]ho is the sovereign, de jure or de facto, of a territory.” Oetjen, 246 U.S. at 302. We therefore are bound bythe decision of the Executive not to recognize the PLO, andwe must apply international law principles accordingly.

22 Classical international law was predominantly statist.The law of nations traditionally was denned as “the body ofrules and principles of action which are binding upon civilized states in their relations with one another.” J. BRIERLY, supranote 11, at 1 (emphasis added); see also G. VON GLAHN, supranote 21, at 61-62; 1 C. HYDE, INTERNATIONAL LAW CHIEFLY ASINTERPRETED AND APPLIED BY THE UNITED STATES § 2A, at 4(2d ed. rev. 1945). Non-state actors could assert their rightsagainst another state only to the extent that their own stateadopted their claims, and as a rule they had no recourseagainst their own government for failure to assist or to turnover any proceeds. 1 C HYDE, supra, § 11B, at 36. See alsoSohn, The New International Law: Protection of the Rights of Individuals Rather than States, 32 AM. U.L. REV. 1, 9(1982). That the International Court of Justice permits onlyparty-states to appear in cases before the court highlights thisoutlook. Article 34(1), Statute of the International Court ofJustice, done June 26, 1945, 59 Stat. 1055, T.S. No. 993, 3Bevans 1153 (entered into force for United States October 24,1945)

23 For example, responding to a “following orders” defense,the court cited Article 8 of the Charter annexed to the agreementestablishing the Nuremberg Tribunal, which declared,“The fact that the defendant acts pursuant to orders of hisGovernment or a superior shall not free him from responsibility,but may be considered in mitigation of punishment.” 6F.R.D. at 110-11.

24 Three other cases have suggested jurisdiction might beavailable under § 1350. Of these, two implicated private defendants.In Nguyen Da Yen v. Kissinger, 528 F.2d 1194 (9thCir. 1975), an action against the Immigration and NaturalizationService and others alleging the illegal seizure and removalof Vietnamese babies from Vietnam in the final hours of U.S.involvement there, the court noted in dicta that jurisdictionmight be available under § 1350, and that, if it were, privateadoption agencies that participated in the “babylift” might bejoined as joint tortfeasors. Id. at 1201 n.13. In a 1907 Opinion,26 Op. Att’y Gen. 250 (1907), the Attorney General indicatedthat a predecessor to § 1350 might provide a forum toMexican citizens seeking redress for damages suffered whenan American irrigation company altered the channel of theRio Grande River. The third case, O’Reilly de Camara v. Brooke, 209 U.S. 45 (1908), suggests that a United States officer's seizure of an alien's property in a foreign countrymight fall within § 1350.

25 At least one law review note has suggested that we decidethis case in favor of plaintiffs by identifying terrorism as alaw of nations violation. See Note, Terrorism as a Tort in Violation of the Law of Nations, 6 FORDHAM INT’L L.J. 236(1982).

26 Signed Feb. 2, 1971, 27 U.S.T. 3949, T.I.A.S. No. 8413(entered into force for United States Oct 20, 1976).

27 Adopted Dec. 17, 1979, GA. Res. 34/146, 34 UN. GAORSupp. (No. 39), UN. Doc A/34/819 (1979).

28 Signed Dec 16, 1970, 22 U.S.T. 1641, T.I.A.S. No. 7192,860 U.N.T.S. 105 (entered into force for United States Oct 18,1971).

29 1 C. HYDE, supra note 22, at 1.

30 To the extent that Judge Robb's reliance on political questionprinciples arises from his concern about court interventionin foreign affairs, the Act of State Doctrine delineatesthe bounds of proper judicial restraint. The doctrine arisesin cases which, under Judge Robb's formula, would be deemedpolitical question cases. Yet, we cannot ignore the fact thatthey are not treated as political question cases and rulednonjusticiable.

31 This case therefore is distinguishable from Crockett v. Reagan, 720 F.2d 1355 (D.C. Cir. 1988), in which a panelof this court recently affirmed the dismissal of an actionon political question grounds. In Crockett, we held that theinquiry into whether United States advisers stationed in ElSalvador were in a situation of imminent hostilities was beyondthe fact-finding power of this court and hence constituteda political question. That case, unlike this one, involved theapportionment of power between the executive and legislativebranches. The case was brought by a group of Congressmenchallenging the President's failure to report to Congress underthe War Powers Resolution. Our opinion adopted that of theDistrict Court, which had articulated an extremely narrowview of the political question doctrine. Even within that narrowview, it was apparent that Baker v. Carr's category of“judicially discoverable and manageable standards” wouldbar judicial interference in the dispute between the twobranches. Here we have no such dispute and no such factfindingproblems and, therefore, no legitimate grounds for afinding of nonjusticiability

1 Appellants have not pursued the appeal against a fifth defendantnamed in the complaint, the Palestine Congress ofNorth America (“PCNA“).

2 The district court dismissed the action against all defendantson the alternative ground that it was barred by the localone-year statute of limitations for certain torts. D.C. CodeAnn. §12-301(4) (1981). Hanoch Tel-Oren v. Libyan ArabRepublic, 517 F. Supp. 542, 550-51 (D.D.C. 1981). Becausewe agree that the complaint was properly dismissed on othergrounds, we need not reach this ground. Nor need we reachthe district court's dismissal of the action against the NAAAand PIO (as well as the PCNA) on the ground that the allegationsof the complaint were insufficiently specific. See note 4 infra.

3 In the district court, appellants also argued that jurisdiction rested on 28 U.S.C. § 1830 (1976) (Foreign SovereignImmunities Act) and on 28 U.S.C. § 1332 (1976) (diversity).The district court rejected both grounds of jurisdiction, 517F. Supp. at 549 n.3, and appellants have abandoned them onappeal.

4 The district court found the complaint's allegationsagainst the PIO and the NAAA (and against the PCNA) insubstantial,vague, and devoid of any factual detail. It thereforeheld those allegations insufficient to support a tort actionfor damages. 517 F. Supp. at 549.

5 Count I charges defendants with the torts of assault,battery, false imprisonment, and intentional infliction ofmental distress; it also charges defendants with a tort itdescribes as the intentional infliction of cruel, inhuman, anddegrading treatment Count IV charges defendants withtortious actions in violation of various criminal laws of theUnited States. Count V charges defendants with conspiracyto commit the torts specified in Counts I through IV.

6 The Tel-Oren plaintiffs are citizens of the United States,and the Drory plaintiffs are citizens of the Netherlands. Theother plaintiffs are citizens of Israel. Air the plaintiffs residein Israel.

7 The Supreme Court also discussed the act of state doctrinein First National City Bank v. Banco Nacional de Cuba, 406 The courts of appeals have likewise emphasized the decisiverole played, in applying the doctrine, by the tworelevant aspects of separation of powers: t n e potentialfor interference with the political branches' functionsand the fitness of an issue for judicial resolution.

8 A plaintiff who has no cause of action is, according to Davis V. Passman, 442 U.S. at 240 n.18, not entitled to “invokethe power of the court” He is not entitled to a pronouncementon the legal merits of his claim. In that respect he is morelike a plaintiff who lacks standing than he is like a plaintifffacing a motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim. Thatis especially true in a case like this, where judicial considerationof the legal merits is of constitutional concern, so thatparties should not be able to waive the claim that no causeof action exists. In these circumstances, whether a cause ofaction exists is a threshold issue that involves a question ofthe limits of judicial powers.

9 “The state as a person of international law should possessHie following qualifications: a) a permanent population;b) a defined territory; c) government; and d) capacity toenter into relations with the other states.” Convention onRights and Duties of States, Dec. 26,1933, art 1,49 Stat 3097,T.S. No. 881,165 L.N.T.S. 19. See also Restatement (Second) of the Foreign Relations Law of the United States § 4 (1965).Furthermore, the act of state doctrine would still not apply,even if the PLO is said to have been the agent of Libya, sincethe attack did not take place “within [Libya's] own territory.” Sabbatino, 376 U.S. at 401.

10 If jurisdiction rested on section 1331, at least one necessaryrule of decision would have to be supplied by internationallaw, the federal law under which the case arose. See FranchiseTax Board v. Construction Laborers Vacation Trust for SouthernCalifornia, 103 S. Ct 2841, 2846-48 (1983). If jurisdictionrested on section 1350, there are three arguabletheories about what law would supply the rule of decision.The rule of decision might be the international law (treaty orcustomary international law) violated; it might be a federalcommon law of torts; or it might be the tort law of whateverjurisdiction applicable choice of law principles would pointto. Cf. Blum & Steinhardt, Federal Jurisdiction over International Human Rights Claims: The Alien Tort Claims Act after Filartiga v. Pena-Irala, 22 Harv. Int’l L.J. 53, 99-100(1981). Under the latter two constructions, of course, whetherinternational law was violated would have to be decided as ajurisdictional prerequisite.

11 A state-court suit that involved a determination of internationallaw would require consideration of much that I discusshere as well as the principle that foreign relations areconstitutionally relegated to the federal government and notthe states. See Zschernig v. Miller, 889 U.S. 429 (1968).

12 The existence of severe separation of powers problems inadjudicating appellants' claims reinforces my conclusion, see infra pp. 88-45, that international law affords appellants nocause of action. The potential for interference with governmentsconducting their foreign relations is central both toseparation of powers limits on jurisdiction and to internationallaw's general refusal to grant private rights of action. Theexistence of such a potential in any case must count stronglyagainst international law's providing a private right of actionfor that case.

13 “Libya must be dismissed from the case because theForeign Sovereign Immunities Act, 28 U.S.C. §§ 1330, 1602-1611 (1976), plainly deprives us of jurisdiction over Libya. See Verlinden B.V. v. Central Bank of Nigeria, 103 S. Ct1962 (1983) (court must decide immunity question, which isjurisdictional). Because the alleged actions of the PIO andthe NAAA all involve giving assistance to the PLO's allegedactions, an adjudication of the claims against them wouldrequire adjudication of the claims against the PLO. If, as Iconclude, the latter presents sufficiently serious problems thatno cause of action can be inferred, so too must the former.I therefore concern myself only with the PLO. Of course,adjudication of the complaint against Libya would presentmany of the same separation of powers problems as wouldadjudication of the complaint against the other defendants.

14 One aspect of this problem is the apparent assumption ofstate action in the definition of certain international legalprinciples. Thus, the United Nations General Assembly hasdefined torture as “any act by which severe pain or sufferingis intentionally inflicted by or at the instigation of a publicofficial.” G.A. Res. 3452, art. 1, 30 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 34)at 91, U.N. Doc. A/10034 (1975). This assumption of stateaction is one reason why it is by no means utterly obviousthat the torture alleged in appellants' complaint would beprohibited by international law.

15 It is worth noting that even the 1972 United StatesDraft Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of CertainActs of International Terrorism, 67 Dep't St. Bull. 431(1972), would present some problems to appellants. First, itmakes motive a key to violation. Second, like the EuropeanConvention on the Suppression of Terrorism, Jan. 27, 1977,15 I.L.M. 1272 (1976), the 1972 Draft Convention relies oncriminal remedies for the vindication of the rights specified,thus leaving the power to invoke remedies in the hands ofstates. Third, the 1972 Draft Convention does not protectcitizens of a state against attack within the state.

16 For example, private enforcement of what is perhaps thefundamental principle of the Charter—the nonaggressionprinciple of article 2, section 4—would flood courts throughoutthe world with the claims of victims of alleged aggression(claims that would be extremely common) and would seriouslyinterfere with normal diplomacy.

17 Because none of the treaties cited by appellants providesthem a cause of action, it is unnecessary to decide whetherany of the treaties imposes duties on parties such as appelleeshere. Thus, in particular, there is no need to inquire into thecontacts with the United States of appellees and their actions.That inquiry is also unnecessary for a decision on Count II ofappellants' complaint, as I conclude that appellants have nocause of action for that count on grounds independent of thecloseness of appellees' United States contacts.

18 The district court rejected it on the general ground that“an action predicated on … norms of international law musthave at its basis a specific right to a private claim” found ininternational law itself. 517 F. Supp. at 549. That formulationis very likely too strong, as it would seem to deny Congressthe power to provide individuals a statutory right ofaction to seek damages for international law violations notactionable under international law itself.

19 Appellants argue that a citizen's access to federal courtsto seek damages for a tort committed in violation of internationallaw should be the same as an alien's access. Internationallaw's special concern for aliens might suggest to thecontrary, 8ee L. Henkin, R. Pugh, O. Schachter & H. Smit, supra, at 685-803, 805, and the restriction of section 1350 toaliens might reflect that concern. This question need not bepursued, however, since, for reasons having nothing to do withappellants' citizenship, they have no cause of action in thiscase.

20 Section 1350, the Alien Tort Claims Act, was enacted bythe First Congress in section 9 of the Judiciary Act of September 24,1789, ch. 20,1 Stat 73, 76-77. The original statuteread: “[T]he district courts … shall … have cognizance,concurrent with the courts of the several States, or the circuitcourts, as the case may be, of all causes where an alien sues fora tort only in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of theUnited States.”

21 In nearly two hundred years, jurisdiction has been predicatedsuccessfully under section 1350 only three times. Filartigav. Pena-Irala, 630 F.2d 876 (2d Cir. 1980) (jurisdictionover allegation of official torture not ratified by official'sstate); Adra v. Clift, 195 F. Supp. 857 (D. Md. 1961) (childcustody dispute between two aliens; wrongful withholding ofcustody is a tort, and defendant's falsification of child's passportto procure custody violated law of nations) ; Bolchos v.Darrel, 3 F. Cas. 810 (D.S.C. 1795) (No. 1607) (suit forrestitution of three slaves who were on board a Spanish shipseized as a prize of war; treaty with France superseded law ofnations; 1350 alternative basis of jurisdiction).

22 That Blackstone refers to these three classes of offensesas not only violations of the law of nations, but censured assuch by the municipal law of England does not require theconclusion that in America these three types of violations didnot carry with them a private cause of action for which section1350 gave the necessary jurisdiction to federal courts. Theformer colonies picked up the law of England as their own.As stated in the Preface to the American Edition of Blackstone:“The common law is as much the birth-right of anAmerican as of an Englishman. It is our law, as well as thelaw of England, it having been brought thence, and establishedhere as far forth as it was found fitted to our institutionsand the circumstances of the country.” W. Blackstone, Commentaries vii (1854) (emphasis in original). Englishstatutes, which were, of course, part of the municipal law,were also adopted as part of American common law, to theextent that their “collective and equitable principles hadbecome so interwoven with the common law, as to be scarcelydistinguishable therefrom.” Fitch v. Brainerd, 2 Conn. 163(1805), quoted in Jones, The Reception of the Common Law in the United States in H. Jones, J. Kernochan, & A. Murphy, Legal Method: Cases and Text Materials (1980). And atleast some offenses against the law of nations, such as violationsof safe-conducts, resulted not only in criminal punishmentbut in restitution for the alien out of the offender'seffects. W. Blackstone, Commentaries 69.

23 The crime of piracy was often defined as piracy jure gentium—piracy by the law of nations, as distinguished frompiracy by municipal law. E.g., 2 J. Moore, A Digest of International Law § 311, at 951-52 (1906); Dickinson, Is the Crime of Piracy Obsolete?, 38 Harv. L. Rev. 334, 335-36(1925) (“The Crime of Piracy“). The crime of piracy wasthought to be sufficiently defined by the law of nations. The Federalist No. 42 (J. Madison) (“The definition of piraciesmight, perhaps, without inconveniency, be left to the law ofnations; though a legislative definition of them is found inmost municipal codes. A definition of felonies on the highseas, is evidently requisite.”). Although the Congress, in definingpiracy in the Federal Crimes Act of 1790 confused theconcepts of piracy defined by the law of nations and piracydefined by municipal law, Act of Apr. 30, 1790, ch. 9, § 8, 1Stat 112,113-14; see The Crime of Piracy at 342-49, Congresslater changed the definition in reaction to the very firstSupreme Court case construing section 8, United States v.Palmer, 16 U.S. (8 Wheat) 610 (1818). The new statutepunished “the crime of piracy, as defined by the law of nations.”Act of Mar. 8, 1819, ch. 77, § 5, 3 Stat. 510, 513-14. See The Crime of Piracy at 342-49. Thus, Justice Story, inUnited States v. Smith, 18 U.S. (5 Wheat.) 71, 75 (1820),wrote that “whether we advert to writers on the commonlaw, or the maritime law, or the law of nations, we shall find,that they universally treat of piracy as an offence againstthe law of nations, and that its true definition by that law isrobbery upon the sea.” Furthermore, in a celebrated footnoteof more than eight and one-half pages, Justice Story showedthat “piracy is denned by the law of nations.” Id. at 75-84.

24 Nor is there any significance to the fact that in The Paquete Habana the court assumed a private cause of action toexist. That case involved a branch of the law of nations—prize jurisdiction under maritime law—which had long recognizedthe right of private enforcement. That, as will be shown,is not universally true of international law and most particularlyis not true of the area in which this case falls.

25 Further evidence that “the Law of Nations is primarilya law between States” is the key role played by nationality inthe availability to individuals of international legal protection.

1 L. Oppenheim, supra, at 640. Even nationals however, cannotthemselves generally invoke that protection: “if individualswho possess nationality are wronged abroad, it is, as a rule, their home State only and exclusively which has a rightto ask for redress, and these individuals themselves have nosuch right” Id.

26 The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rightsdirects states to provide a forum for private vindication ofrights under the Covenant. That provision, however, shouldnot be taken to suggest the Covenant grants or recognizes aprivate right of action in municipal courts in a case like this.First, the Covenant directs states to provide forums only forthe vindication of rights against themselves, not for the vindicationof rights against other states. It is only the latter thatraises all the political, foreign relations problems that liebehind international law's general rule against private causesof action; thus, even if the Covenant suggests recognition ofa private cause of action for the former, it does not do so forthe latter. Second, the Covenant does not itself say individuals can sue; rather, it leaves to states the fulfillment of an obligationto create private rights of action.

27 See, e.g., Meeting with Hispanic, Labor, and ReligiousPress, 19 Weekly Comp. Pres. Doc. 1245, 1248-49 (Sept. 14,1983) (President Reagan's response to question: “[0]ne ofthe reasons why we would never negotiate with the PLO,[is] because they openly said they denied the right of Israelto be a nation.”); Foreign and Domestic Issues, Question-and-Answer Session with Reporters, 19 Weekly Comp. Pres. Doc.643, 647-48 (May 4, 1983) (President Reagan's response toquestion: “[A]re they going to stand still for their interestsbeing neglected on the basis of an action taken by this group,the PLO, which, as I say, was never elected by the Palestinianpeople?”) ; N.Y. Times, Nov. 10, 1983, at A12, col. 5 (remarksof Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs Lawrence S.Eagleburger). And, most recently, the New York Times reportedon its front page Secretary of State George P. Shultz'scomments that “the outcome of the struggle within the PalestineLiberation Organization was certain to have 'major implications’for the future of the American-sponsored peace effortsin the Middle East.” N.Y. Times, Nov. 20, 1983, at Al, col. 5.

1 See, e.g. Implementation of the Helsinki Accords, Hearing Before the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, The Assassination Attempt on Pope John Paul II, 97th Cong.,2d Sess. 20 (Statement of Michael A. Ledeen) (“[M]anyterrorist organizations get support from the Soviet Union andits many surrogates around the world. I do not think thereshould be much doubt about the matter. The Russians trainPLO terrorists in the Soviet Union, supervise the trainingof terrorists from all over the world in Czechoslovakia—or atleast they did until recently, according to a leading defector,General Jan Sejna—and work hand in glove with countrieslike Libya, Cuba, and South Yemen in the training of terroists.”) See also Adams, Lessons and Links of Anti-Turk Terrorism, Wall St J., Aug. 16, 1988, at 82, col. 6 (TheArmenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia “remainsa prime suspect for the charge of E68 manipulationof international terror. But in this area, one researcher in thefield advises, ‘You will never find the smoking gun’.”); Barron, KGB 151, 255-257 (1974); Barron, KGB Today: The Hidden Hand, 21-22, 255-256 (1983).

2 Note, Terrorism as a Tort in Violation of the Law of Nations, 6 Fordham Int’l L.J. (1982).

3 C. Sterling, The Terror Network (1981). Sterling repeatedlypoints out, and often criticizes, the reluctance ofWestern governments to openly detail the international cooperationthat girds most terrorist activities. She writes:No single motive could explain the iron restraint shownby Italy, West German, and all other threatened Westerngovernments in the face of inexorably accumulating evidence.… Both, and all their democratic allies, also hadcompelling reasons of state to avoid a showdown with theSoviet Union… . All were certainly appalled at thethought of tangling with Arab rulers… .[PJolitdcal considerations were almost certainly paramountfor government leaders under seige who …wouldn't talk.

4 See, e.g., Haig v. Agee, 453 U.S. 280, 292 (1981) (“Mattersintimately related to foreign policy are rarely proper subjectsfor judicial intervention.) ; Dames & Moore v. Regan, 453U.S. 654 (1981).

5 I do not doubt for a moment the good intentions behindJudge Eauffman's opinion in FUartiga. But the case appearsto me to be fundamentally at odds with the reality of the internationalstructure and with the role of United States courtswithin that structure. The refusal to separate rhetoric fromreality is most obvious in the passage which states that “forthe purposes of civil liability, the torturer has become—likethe pirate and slave trader before him— hostis humani generis,an enemy of all mankind.” 630 F.2d at 890. This conclusionignores the crucial distinction that the pirate and slave traderwere men without nations, while the torturer (and terrorist)are frequently pawns, and well controlled ones, in internationalpolitics. When Judge Kauff man concluded that” [oj ur holdingtoday, giving effect to a jurisdictional provision enacted byour First Congress, is a small but important step in the fulfillmentof the ageless dream to free all people from brutalviolence,” id., he failed to consider the possibility that ad hoeintervention by courts into international affairs may verywell rebound to the decisive disadvantage of the nation. Aplaintiff's individual victory, if it entails embarassing disclosuresof this country's approach to the control of the terroristphenomenon, may in fact be the collective's defeat Thepolitical question doctrine is designed to prevent just thissort of judicial gambling, however apparently noble it mayappear at first reading.

* [Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Department off Justice. The brief was filed on January 30, 1985. On February 25, 1985, the Supreme Court refused to hear the appeal.]

1 Although the caption of this case identifies Libya as theLibyan Arab Republic, the official name of the country is the Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya.

2 The complaint also asserted jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C.1330 and 1332, but petitioners abandoned these grounds of jurisdiction in the court of appeals (Pet. App. 54a n.3).

3 The district court did not reach the question whether theconduct complained of violated the law of nations. Pet. App.119a.

4 In addition to the PIO and the NAAA, petitioners' complaintalso named as a defendant a third Arab-Americangroup, the Palestine Congress of North America (PCNA).The district court dismissed the action against the PCNAon the same grounds as the action against the two other Arab-American groups, and petitioners did not pursue theirclaims against the PCNA on appeal (Pet. App. 2a n.l).

5 In a footnote, Judge Edwards agreed with the districtcourt that jurisdiction over Libya was barred by the ForeignSovereign Immunities Act, 28 U.S.C. 1330, 1602-1611, andthat petitioners' allegations against the Arab-American organizationswere “too insubstantial to satisfy the § 1350 requirementthat a violation of the law of nations be stated”(Pet. App. 4a n.l). Judge Edwards also disposed of petitioners’reliance on 28 U.S.C. 1331 in a footnote. He waswilling to assume for the sake of argument that the law of nationsconstitutes a “law of the United States” for purposesof the federal question statute, but he concluded that petitionerscould not identify any right to sue granted by the lawof nations and also observed that “the law of nations quitetenably does not provide these plaintiffs with any substantiveright that has been violated” (Pet. App. 13a n.4). JudgeEdwards expressed no view on the correctness of the districtcourt's statute of limitations ruling.

6 Judge Edwards also put forth an alternative hypothesiswith respect to the meaning of the alien tort statute. Underthat theory, the statute was simply intended “to assure aliensaccess to federal courts to vindicate any incident which, ifmishandled by a state court, might blossom into an internationalcrisis” (Pet. App. 19a). Even under this theory,however, Judge Edwards concluded that petitioners could notmaintain their suit because of the PLO's status as a nonstateand the absence of any international consensus thatpolitically-motivated terrorism is an international crime.

7 Because he found that the complaint was correctly dismissedon jurisdictional grounds, Judge Bork did not reachthe questions whether the district court had properly dismissedthe action against the Arab-American organizationson the grounds that the allegations of the complaint wereinsufficiently specific and the action was barred by the localstatute of limitations (Pet. App. 53a n.2). Judge Bork alsodeclined to decide the question whether the PLO, as a nonstate,should be subject to obligations imposed by internationallaw (id. at 67a-69a).

8 Petitioners' third question, regarding the applicability ofthe political question doctrine to cases of this kind (Pet. i,23-27), could be significant in another case but is not properlypresented here, because a majority of the panel votedto affirm the dismissal on other grounds, thereby avoidingapplication of the political question doctrine. See Pet. App.48a-52a (Edwards, J., concurring); id. at 63a n.8, 103a-104a(Bork, J., concurring).

9 Judges Edwards and Bork even disagreed about the extentof their disagreement. Although Judge Edwards identifiedfour central propositions over which he believed he and hiscolleagues differed (Pet. App. 7a-8a), Judge Bork stated that,in fact, he “accept [ed] the first three [propositions] entirelyand also agreefd] with the fourth, but in a more limitedform” (id. at 98a). For his part, Judge Edwards remarkedthat Judge Bork “has completely misread my opinion” (id.at 52a)

10 In Filartiga, the Second Circuit held that the alien tortstatute conferred federal jurisdiction over a suit brought byParaguayan nationals against a former Paraguayan policeofficial for wrongfully causing the death of their relative inParaguay, allegedly by the use of torture. Judge Bork concludedthat Filartiga differs from this case in three importantrespects: unlike the PLO in this case, the defendant in Filartiga,a state official acting in his official capacity and in directcontravention of the Paraguayan constitution and laws, “wasclearly the subject of international-law duties, the challengedactions were not attributed to a participant in Americanforeign relations, and the relevant international law principlewas one whose definition was neither disputed nor politicallysensitive” (Pet. App. 97a). These factual distinctions ledJudge Bork to conclude that “not all of the analysis employedhere would apply to deny a cause of action to the plaintiffs in Filartiga” (ibid.). Judge Bork's quarrel with Filartiga wasbased on an issue that the Second Circuit did not address—the question whether international law created a cause of actionthat the plaintiffs before it could enforce in United Statescourts. Similarly, Judge Edwards “adhere [d] to the legalprinciples established in Filartiga but [found] that factualdistinctions [relating to the PLCs status as a non-state actoras opposed to a person acting under color of state law] preclude[d] reliance on that case to find subject matter jurisdictionin the matter now before us” (Pet. App. 5a).

11 In our brief on appeal in Sanchez-Espinoza, we haveargued that the alien tort statute is purely jurisdictional andcannot be interpreted either to mandate the creation of afederal common law of international tort or to authorizeindividuals to enforce in domestic courts private rights ofaction derived directly from customary international law. SeeBr. for the Federal Appellees at 9, 32-40. We have also arguedthat the alien tort statute does not waive either the sovereignimmunity of the United States or the official immunities ofindividual government officials from alien tort claims arisingout of actions in foreign countries. See id. at 40-44.

12 In addition to the District of Columbia Circuit, otherfederal courts also are considering claims based on the alientort statute. See, e.g., Siderman de Blake v. Republic of Argentina,No. CV 82-1772-RMT (MCx) (CD. Cal. Sept. 28,1984) (awarding a default judgment to Argentinian plaintiffswho claimed official torture by the Argentinian government inArgentina, predicating jurisdiction on Section 1350). We areadvised that the district court is reconsidering its judgmentin Siderman de Blake in light of the Foreign Sovereign ImmunitiesAct.

13 As described by Judge Edwards, the alien tort statute is“an aged but little-noticed provision of the First JudiciaryAct of 1789” (Pet. App. 4a). It has been invoked only rarelyin its nearly 200-year history; indeed, “[t]his old but littleused section is a kind of legal Lohengrin; * * * no one seemsto know whence it came.” IIT v. Vencap, Ltd., 519 F.2d 1001,1015 (2d Cir. 1975). Clearly, further elucidation by the lowercourts of the issues raised in the petition would be of assistanceto this Court.

14 Judge Edwards specifically agreed with this aspect of thedistrict court's decision (Pet. App. 4a n . l ) . Judge Robb didnot discuss the issue, and Judge Bork declined to pass on it (id. at 53a n.2, 55a n.4). Nevertheless, Judge Bork confinedhis jurisdictional analysis wholly to petitioners' allegationsagainst the PLO (id. at 67a n.13)o[Reproduced from the Provisional Edition provided by the Councilof Europe.