No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

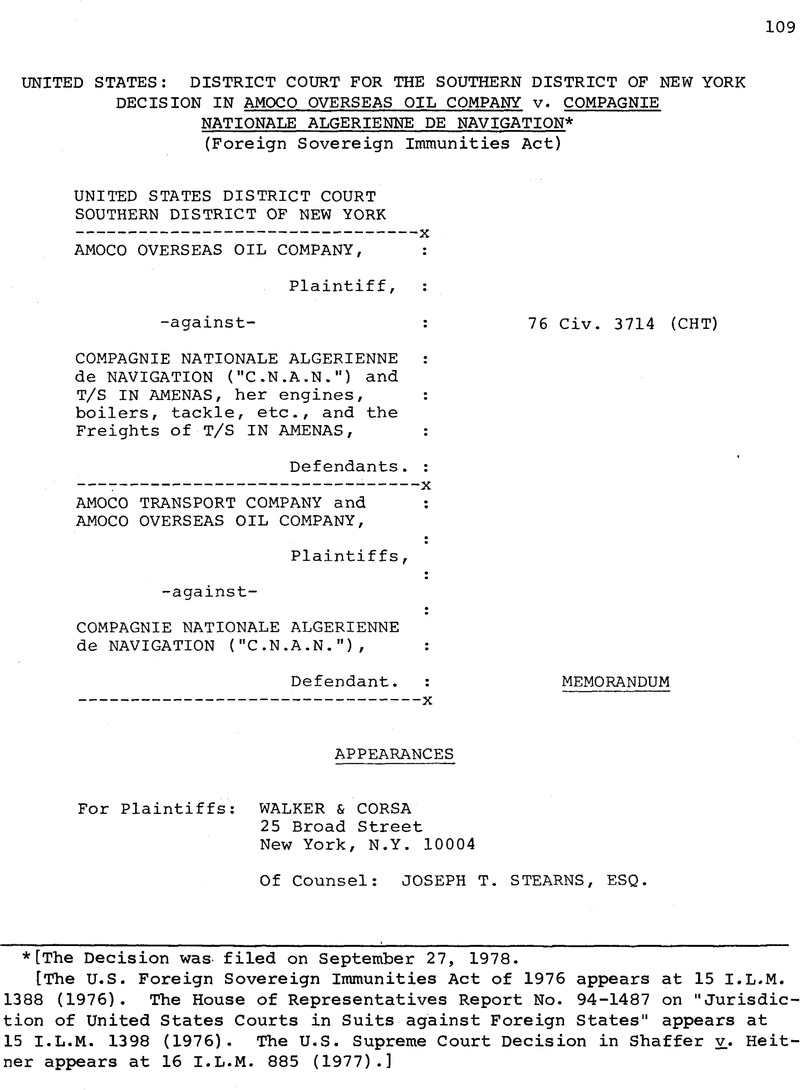

[The Decision was filed on September 27, 1978.]

[The U.S. Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976 appears at 15 I.L.M. 1388 (1976). The House of Representatives Report No. 94-1487 on "Jurisdiction of United States Courts in Suits against Foreign States" appears at 15 I.L.M. 1398 (1976). The U.S. Supreme Court Decision in Shaffer v. Heitner appears at 16 I.L.M. 885 (1977).]

1 The plaintiffs are mistaken in this contention. Rule 60(b) is directed, inter alia, at a “final judgment,” and it is clear that the “essence of a final judgment is that it leaves for the court nothing to do but order execution.” International Controls Corp. v. Vesco, 535 F.2d 742, 748 (2d Cir. 1976). Because damages had not yet been established in this action on October 27, 1976, the default judgment for inquest entered on that date was not “final”; that adjective is reserved for the April 1, 1977, amended default judgment in a sum certain. See note 7, infra.

2 In Carroll v. Manufacturers Trust Co., 202 F.2d 715 (2d Cir. 1953), the plaintiff attempted to circumvent the ninety-day attachment renewal stricture of former New York Civil Practice Act § 922(1) by invoking federal Rule 6(b), which provides that a court may enlarge the time in which an act is to be done. The court responded that it was “governed by New York law,” which at that time provided “that an extension may be made by order of the court only within the original ninety day period.” Id. at 716.

3 See note 2 supra.

4 Absent statutory authority, the traditional judicial concept of nunc pro tunc orders would not sanction the cure of a jurisdictional defect in this manner. “All courts have the inherent power to enter orders nunc pro tunc to show that their previous unrecorded acts ought to have been shown at that time.” Cairns v. Richardson, 457 F.2d 1145, 1149 (10th Cir. 1972). However, the nunc pro tunc order “cannot supply an order which in fact was not previously made.” Crosby v. Mills, 413 F.2d 1273, 1277 (10th Cir. 1969). Indeed, the New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division has stated that where “the subject matter is jurisdictional the error cannot be corrected by an order nunc pro tunc.” Smith v. State, 53 App. Div. 2d 756, 758, 384 N.Y.S.2d 517, 520 (3d Dep’t 1976) (statute of limitations on claim ran before plaintiff administratriv named to represent decedent’s estate; no cure by amendment nunc pro tunc). Here, however, the Court is dealing with a statute that explicitly permits the continuation of time to perfect otherwise validly acquired jurisdiction, and since the manner of perfection is, within the limits of due process, a matter of legislative discretion, the legislature had the power to promulgate a statute authorizing the courts to perfect jurisdiction nunc pro tunc. See Medina, Current Developments in Pleading, Practice and Procedure in the New York Courts, 30 Cornell L.Q. 449 (1945) (commenting on issuance of nunc pro tunc corrections under the predecessor to section 6214(e), which required that an extension be obtained before the initial ninety days elapsed: “Perhaps the courts may take a more lenient view, but I do not see how the validity of nunc pro tunc orders can be reconciled with the section as it now reads.” Id. at 459 (emphasis added)).

5 The statute makes no distinction between extensions on attachments made in aid of security or those obtained as a jurisdictional base.

6 It may be argued that the Seider res, a liability insurer’s contractual obligation to defend and indemnify, is peculiarly incapable of reduction to possession, and that the Seider extension was justified in a way that is not analogous to the facts at bar. Indeed, the defendants point to language in Seider that endorsed the extension “in view of the novelty of the question, the uncertain state of the law and the fact that the requirement of CPLR 6214 is largely ministerial as it relates to intangible property.” Seider v. Roth, supra, 28 App. Div. 2d at 699, 280 N.Y.S.2d at 1007. However, defendants’ argument addresses only the merits of this Court’s action in granting the extension, an attack on the correctness rather than the legitimacy of the decision. Rule 60(b) is not a substitute for appeal. Burnside v. Eastern Airlines, Inc., 519 F.2d 1127, 1128 (5th Cir. 1975). Furthermore, amended section 6214(e) makes no distinction between tangible or intangible property, nor does it condition the exercise of the court’s discretion in granting the extension upon the ease or difficulty with which possession can be effected.

7 According to the Court’s analysis concerning the validity of jurisdiction during the entire proceedings, the April 1, 1977, amended default judgment appears to have been a superfluity. However, since it was in the same amount as the valid March 23, 1977, default judgment, the error is harmless.