No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

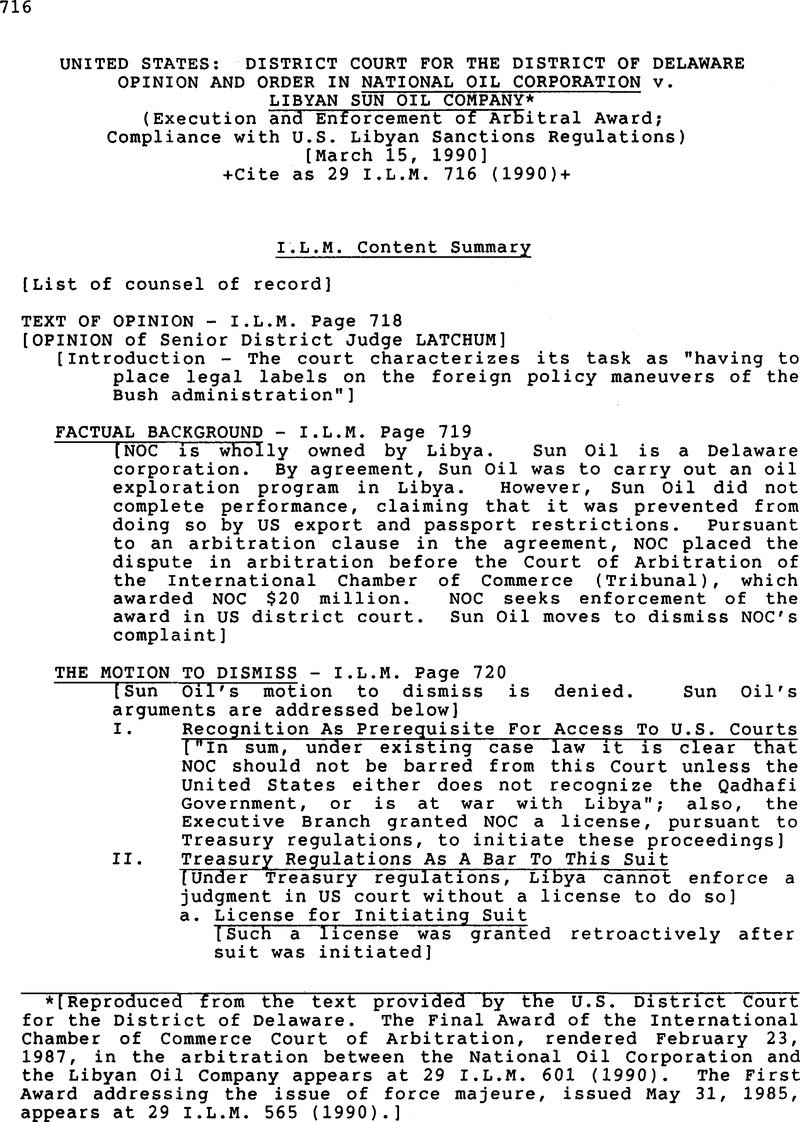

* [Reproduced from the text provided By the U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware. The Final Award of the International Chamber of Commerce Court of Arbitration, rendered February 23, 1987, in the arbitration between the National Oil Corporation and the Libyan Oil Company appears at 29 I.L.M. 601 (1990). The First Award addressing the issue of force majeure, issued May 31, 1985, appears at 29 I.L.M. 565 (1990).]

1 The arbitral award in dispute here was issued in Paris, France, under the auspices of the International Chamber of Commerce. France is a signatory of the Convention, and hence the requirement of reciprocity is satisfied. See 9 U.S.C. § 201 (West Supp. 1989).

2 That clause reads as follows:22.1 Excuse of Obligations Any failure or delay on the part of a Party in the performance of its obligations or duties hereunder shall be excused to the extent attributable to force majeure. Force majeure shall include, without limitation: Acts of God; insurrection; riots; war; and any unforeseen circumstances and acts beyond the control of such Party.(D.I.3, Exhibit A, Annex 1, EPSA 22.1, at 45-46.).

3 The passport regulation, issued pursuant to an executiveorder, stated that “United States passports shall cease to bevalid for travel to, in, or through Libya unless specifically validated for such travel under the authority of the Secretary of State.“ 46 Fed. Reg. 60,712 (1981).

4 The arbitration clause states: 23.2 Arbitration Any controversy or claim arising out of or relating to this Agreement, or breach thereof, shall, in the absence of an amicable arrangement between the Parties, be settled by arbitration, in accordance with the Rules of Conciliation and Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce, in Paris, France, by three arbitrators. Each Party shall appoint its arbitrator, and the International Chamber of Commerce shall appoint the third arbitrator who must be in no way related to either Party and who will be the chairman of the arbitration body.(D.I. 3, Exhibit A, Annex 1, EPSA J 23, at 47.).

5 The Libyan “government has been characterized by the Presi¬dent of the United States as an 'outlaw regime' and a 'pariah in the world community,'” and it has been “implicated in terrorist attacks throughout the world on United States citizens.” (D.I.12 at 14-15 [footnotes omitted].) Moreover, Libya's military forces have attacked U.S. forces, and U.S. forces have responded. The United States Embassy in Tripoli is closed as is the Libyan “Peoples' Bureau” in Washington, and virtually all economic transactions between the United States and Libya have been prohibited by the U.S. Government. The President has declared that there is currently a “national emergency” with respect to Libya… .(Id., at 15 [footnotes omitted].).

6 Sun Oil also argues that Pfizer. 434 U.S. at 319-20, presentsa more precise articulation of the recognition-access analysisapplied in Sabbatino. 376 U.S. 398.(See D.I. 16 at 2-5.)Pfizer, according to Sun Oil, establishes a two-part “test” fordetermining whether a foreign government is entitled to access toour courts: first, is the foreign government “recognized” and,secondly, is it “at peace” with the United States?See Pfizer.434 U.S. at 319-20; see also supra pp. 6-7. Sun Oil maintainsthat even if Libya were thought to be “recognized,” recentviolent exchanges between our two countries mean that we arenonetheless not “at peace.”(D.I. 16 at 3.) The Court rejects this argument because the Pfizer language is merely dicta, and the opinion does not otherwise demonstrate an intent to alter Sabbatino's reasoning. Moreover, as a practical matter, it is unlikely that this Court could determine whether the current level of tension in U.S.-Libyan relations was sufficient to warrant a finding that our countries are not “at peace,” given the lack of a formal declaration of war from Congress. Such a determination would be nonjusticiable under the political question doctrine. See E. Chemerinsky, Federal Jurisdiction § 2.6, at 136-37 (1989).

7 Only the Executive Branch has the power to recognize aforeign government and, hence,determine which nations areentitled to sue in U.S. courts.See Pfizer Inc. v. Government of India, 434 U.S. at 319-20.

8 When the President has declared a national emergency pursuant to 50 U.S.C. § 1701 of the IEEPA, he is authorized, “under such regulations as he may prescribe, by means of instructions, licenses, or otherwise,” to: (A) investigate, regulate, or prohibit— (i) any transactions in foreign exchange, (ii) transfers of credit or payments between, by, through, or to any banking institution, to the extent that such transfers or payments involve any interest of any foreign country or a national thereof, (B) investigate, regulate, direct and compel,nullify, void, prevent or prohibit, any acquisition, holding, withholding, use, transfer, withdrawal, transportation, importation or exportation of, or dealing in, or exercising any right, power, or privilege with respect to, or transactions involving, any property in which any foreign country or a national thereof has any interest; by any person, or with respect to any property, subject to the jurisdiction of the United States. 50 U.S.C. §1702(a)(1).

9 On January 4, 1990, in accordance with the requirements of the National Emergencies Act, 50 U.S.C. S 1622(d) (West Supp. 1989); see also IEEPA, 50 U.S.C. §§ 1703(d) t 1706 (West Supp. 1989), President Bush continued the state of emergency previously declared with respect to Libya. 55 Fed. Reg. 589 (1990).

10 Under the Regulations, the term “Government of Libya” specifically includes a corporation that, like NOC, is “substantially owned or controlled” by the Libyan Government. See 31 C.F.R. pt. 550, § 550.304(2).

11 Although apparently this is the first time the Libyan Regulations have been interpreted, the cases relied on by NOC are persuasive because the language of the pertinent provisions is so similar to that interpreted by these other courts. Compare 31 C.F.R. S 550.210(e) (Libyan Regulations) with 31 C.F.R. § 535.203(c) (Iranian Regulations).

12 The President had purported to act pursuant to his powers under the IEEPA and 22 U.S.C. § 1732, the “Hostage Act.” Exec. Order No. 12294, 46 Fed. Reg. 14111 (1981). The Court rejected the notion that either statute authorized suspension of claims in U.S. courts. Dames & Moore. 453 U.S. at 678. But the Court went on to conclude based on “inferences [that could] be drawn from the character of the legislation Congress ha[d] enacted in the area, such as the IEEPA and the Hostage Act, and from the history of acquiescence in executive claims settlement… that the President was authorized to suspend pending claims. …” Id. at 686.

13 Although NOC is petitioning to confirm an arbitral award, its claim merely seeks confirmation by this Court of Sun Oil's liability, albeit as established by the Arbitral Tribunal. The effect of entering judgment in this case would be the same as if NOC had sued Sun Oil for breach of contract, instead of moving for confirmation of an arbitral award finding Sun Oil liable for that breach.

14 Sun Oil makes reference to several other statutes, pursuant to which—along with the IEEPA—the President claimed to be acting when he ordered promulgation of the Libyan Regulations. (D.I. 25 at 11 n.ll.) Sun Oil has not argued that any statute other than the IEEPA provides the President with authority to regulate the entry of judgments. The Court would just note, however, that none of these other statutes furnishes any such authorization in this case. See, e.g.. National Emergencies Act, 50 U.S.C. §§ 1601 et seq. International Security and Development Cooperation Act of 1985, 22 U.S.C. §§ 2349aa-8 to 2349aa-9; Federal Aviation Act of 1958, 49 U.S.C. S 1514; 3 U.S.C. § 301.

15 see supra note 12.

16 Sun Oil argues that blocking regulations such as the Libyan Regulations have been upheld numerous times in the past. As stated previously, however, see infra pp. 15-17, virtually every time the regulations were upheld they were read as not barring the mere entry of judgment.

17 This result does not hamper the President's ability to meet foreign policy objectives that necessitate keeping undesirable foreign governments out of U.S. courts. The President can always refuse in the first instance to recognize such a government; or he can derecognize a recognized government that later displeases his administration. See supra pp. 5-11. Furthermore, as noted previously, see supra pp. 9-11, in this case at least, the Executive Branch has indicated that it prefers that the suit proceed.

18 The Court acknowledges what NOC has repeatedly pointed out: Sun Oil's various arguments, regarding the relationship between the Regulations and the jurisdiction of this Court, are arguably irreconcilable. (Compare D.I. 16 at 6 with D.I. 25 at 12-15.)

19 Sun Oil claims this first argument for urging non-recognition of the award is based on two of the Convention's enumerated defenses, namely sections 1(b) and 2(b) of Article V. Section 1(b) provides a defense against recognition of an award upon proof that "[t]he party against whom the award is invoked was not given proper notice of the appointment of the arbitrator or of the arbitration proceedings or was otherwise unable to present his case...." Section 2(b) provides that an award may be refused recognition if its enforcement or recognition "would be contrary to the public policy" of the country in which recognition is sought.

20 The Arbitral Tribunal concluded Mr. Blom's position as head of Eastern Hemisphere Exploration meant be was in charge of Occidental's Libyan operations. (See D.I. 3, Exhibit B, FirstAward at 51.)

21 Bonar v. Dean Witter Reynolds, Inc., 835 F.2d 1378 (llth Cir. 1988), on which Sun Oil relies, presents very different facts. First, as NOC emphasizes, the appellants in Bonar were not given advance notice that the expert in question was going to testify, while Sun Oil received information about Mr. Blom over half a year in advance. Secondly, the misperception as to the Bonar expert's credentials was caused bv the expert, who deliberately perjured himself on the stand. Even more importantly, however, the “expert” in fiojiar. turned out be an actual take. That is, he lied about all of his credentials—where he went to school, what degrees he had, and what jobs he had held. Mr. Blom, on the other hand, was completely truthful about his credentials. It was the Tribunal itself that drew the wrong conclusion. Moreover, this “error” was not material. Even though Mr. Blom was not in Libya or in charge of Occidental's Libyan operations during the period when the EPSA was negotiated and in effect, Sun Oil has not argued that he was not qualified to give an expert opinion as to the meaning of the EPSA or market conditions for qualified personnel for oil exploration activities in Libya. Unlike the Bonar “expert,” Mr. Blom did have legitimate credentials: he had previously lived and worked in Libya, and during the relevant period was still working as a vice president for Occidental.

22 As already explained, see supra p. 4, the first set of hearings were held in 1984 and resulted in the issuance of the Tribunal's “First Award,” which determined that Sun Oil had not properly invoked the Epsa's force maieure provisions. Subsequently, more hearings were held in December of 1985 and June of 1986. In February of 1987, the Tribunal issued its “Final Award,” which dealt with the issues of liability and damages. Mr. Blom testified initially during the pre-First Award hearings. A transcript is available of this testimony. (See D.I. 15A, Exhibit 6B.) Mr. Blom testified a second time in June of 1986. Apparently, no transcript of this testimony is available.

23 Even if this were viewed as an impropriety on NOC's part, such misconduct would not be sufficient grounds for refusing to recognize the Tribunal's award. In light of all of the facts, the Court finds that NOC's failure to act affirmatively to correct the Tribunal's misunderstanding regarding Mr. Blom's credentials is hardly the type of misconduct that would deprive Sun Oil of a fair hearing. Cf. Apex Fountain Sales, Inc. v. Kleinfeld, 818 F.2d 1089, 1094 (3d Cir. 1987) (“[M]isconduct apart from corruption, fraud, or partiality in the arbitrators justifies reversal only if it so prejudices the rights of a party that it denies the party a fundamentally fair hearing.“).

24 Contrary to Sun Oil's assertions, the Court concludes that Mr. Blom's inaccurate statement that Occidental had used some Canadian employees of its Canadian subsidiary was not material to the Arbitral Tribunal's decision. The Tribunal's own characterization of Mr. Blom's testimony illustrates the fact that the critical issue was whether any non-Americans, not necessarily Canadians, were available to replace Sun Oil's American personnel in Libya: Mr. BLOM has testified that Occidental Oil Corporation was able to continue its Libyan production and exploration operations despite the Passport Order by replacing, within a few months, no less than 230 American nationals by an equal number of non-U.S. personnel partly from within the Occidental group of companies, partly from outside sources. (D.I. 3, Exhibit B, First Award at 51 [emphasis added].)

25 Harre v. A.H. Robins Co., Inc., 750 F.2d 1501 (11th Cir. 1985), vacated in part. 866 F.2d 1303 (11th Cir. 1989), is therefore inapposite. The Harre court simply concluded that the appellant's Rule 60(b) motion for a new trial should have been granted where the record showed that “a material expert witness testified falsely on the ultimate issue in the case. …[and] the defense attorneys knew or should have known of the falsity of the testimony.“ Harre. 750 F.2d at 1503 (emphasis added). Here, the Court finds that the inaccurate testimony did not relate to an ultimate issue in the case.

26 NOC's counsel, Mr. Riedinger, objected during the June 1986 hearing before the panel to the introduction of any evidence on this subject [i.e. Mr. Blom's prior testimony], and objected to any questioning of Mr. Blom on this subject by either the panel or Sun's counsel. While one of the arbitrators had begun to question Mr. Blom, that inquiry stopped abruptly after Mr. Riedinger's objections. The panel thus received no evidence on this subject and expressed no views on it in its Awards or elsewhere.’ (D.I.16 at 15.)

27 Recognition may be denied if “[t]he award deals with a difference not contemplated by or not falling within the terms,of the submission to arbitration, or it contains decisions on matters beyond the scope of the submission to arbitration….“ Convention, art. V, sec. l(c).

28 When submitting a dispute to arbitration, the parties can request that the arbitrators act as amiable compositeurs, which means that the arbitrators can “tak[e] into consideration not only legal rules, but also what they believe justice, fairness, and equity direct[].” Lecuyer-Thieffry & Thieffry, Negotiating Settlement of Disputes Provisions in International Business Contracts; Recent Developments in Arbitration and Other Processes. 45 Bus. Law. 577, 591 (1990).

29 Sun Oil made the same jurisdictional argument before the Tribunal. It was rejected for reasons similar to those stated by this Court.(See D.I.3, Exhibit C, Final Award at 17-20.)

30 The Tribunal commented that although Article 8.2 of the EPSA could “lead to rather severe and rigid consequences for the party undertaking exploration operations… it must be kept in mind that…the EPSA is a risk contract.” (D.I. 3, Exhibit C, Final Award at 32 [emphasis added].) In return for a “tax-free percentage share” of any crude oil discovered and produced, Sun Oil “undertook an unconditional and absolute duty to render a counter-performance which consisted either in the timely completion of the exploration operations or, if SUN-OIL did not complete these operations within the prescribed time, in the payment by Sun-Oil of the costs of the uncompleted part thereof.” (Id.) Although this was a “heavy commitment,” it was not a burden sufficient “to deter one dozen other petroleum companies from entering into more or less identical EPSA's with N.O.C. in or about 1980.” (Id.)

31 Article 21 of the EPSA states: “This Agreement shall be governed by and interpreted in accordance with the laws and regulations of the Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, including the Petroleum Law.”(D.I. 3, Exhibit A, Annex 1, EPSA 1 21, at 45.)

32 To some extent, Sun Oil's due process argument is really a claim that the Tribunal erred in its interpretation of Libyan law. A mere error of law would not, however, be sufficient grounds to refuse recognition of the award. Restatement (Third) of the Foreign Relations Law of the United States § 488 comment a (1987); see. Northrop Corp. v. Triad Int'l Mktg. S.A., 811 F.2d 1265, 1269 (9th Cir.), cert, denied. 484 U.S. 914 (1987); cf. Brandeis Intsel Limited v. Calabrian Chemicals Corp., 656 F. Supp. 160, 165 (S.D.N.Y. 1987) (not even “manifest disregard of the law” would be sufficient to deny recognition of a foreign arbitral award based on the Convention's public policy exception) . Moreover, here there is no reason to believe the Tribunal made any error whatsoever.

33 The Court would also note that Sun Oil has revealed its own brand of hypocrisy. It portrays its behavior as an attempt to cooperate with the anti-terrorist foreign policy of the United States. But what Sun Oil conveniently overlooks is the fact that the Qadhafi Government was already considered to be hostile to U.S. interests when the EPSA was negotiated. For example, Sun Oil's own papers underscore that almost one year before the EPSA was entered into, the U.S. Embassy in Tripoli was set on fire by a Libyan mob, and the Libyan authorities did not respond to protect the Embassy. Numerous other Libyan guerilla and terrorist efforts were also known and documented. (See generally D.I. 16, Exhibit 1, Libya Under Oadha; A Pattern of Aggression at A1-A13 [State Department documents outlining Libyan activities].)

34 In light of the circumstances presented here, the Court need not express any opinion as to whether, when, or to what extent a foreign policy objective or dispute might ever be sufficiently compelling to warrant invocation of the Convention's public policy defense against confirmation of a foreign arbitral award.

35 It is also important to note that the U.S.Government hasdemonstrated that it is more than able to indicate when a company such as Sun Oil must abandon its international contractual obligations for the good of our country. In early 1986, over four years after Sun Oil first invoked the force maieure defense and suspended performance, the President of the United States directed the promulgation of the Libyan Sanctions Regulations. See supra pp. 11-12. These regulations expressly prohibit, inter alia, the performance by any U.S. person of any unauthorized “contract in support of an industrial or other commercial or governmental project in Libya.” 31 C.F.R. § 550.205.

36 Sun Oil asserts that Libyan law determines the appropriate rate of prejudgment interest. According to the Third Circuit, however, federal law controls this issue, and federal law calls for the district court to exercise its discretion. See Sun Ship, Inc. v. Hatson Navigation Co., 785 F.2d 59, 63 (3d Cir. 1986).