No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

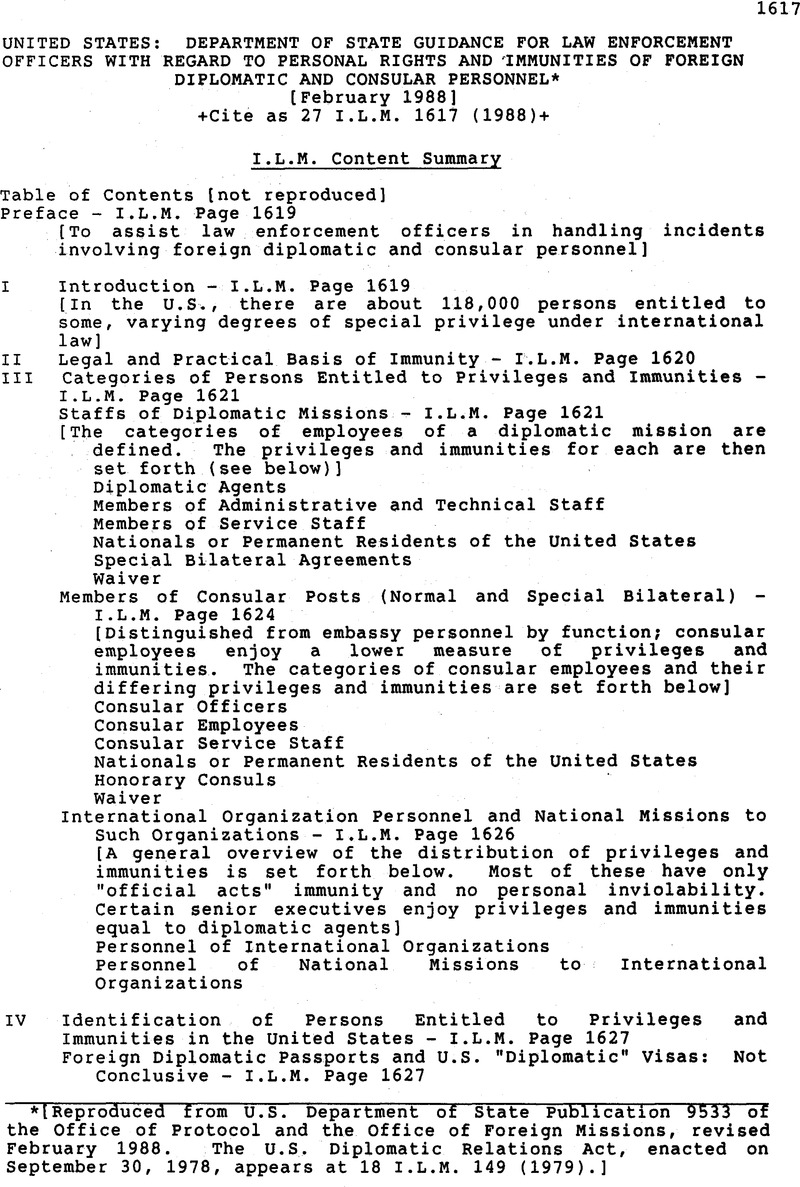

* [Reproduced from U.S. Department of State Publication 9533 of the Office of Protocol and the Office of Foreign Missions, revised February 1988. The U.S. Diplomatic Relations Act, enacted on September 30, 1978, appears at 18 I.L.M. 149 (1979).]

1 The definition of these categories is necessarily general since the category into which specific individuals fall may differ depending on reciprocal practices with the countries concerned. Law enforcement personnel, however, do not need to worry about these fine distinctions in operational situations. Their burden is simply to assure that the appropriate degree of immunity is afforded once the person concerned has been precisely identified.

2 The private servants of diplomatic personnel enjoy no jurisdictional immunity or inviolability in the United States and are therefore not discussed in this booklet.

3 The Department of State has placed limits on who may be considered “family” in this connection. In summary, it is only spouses, and children until the age of 21 (until the age of 23 if they are full-time students at an institution of higher learning), and such other persons expressly agreed to by the Department in extraordinary circumstances.

4 At present, there are such agreements with the U.S.S.R., China, and the German Democratic Republic (East Germany).

5 The United States has, however, concluded special Consular Conventions with such countries as the U.S.S.R.. China, Poland, East Germany (German Democratic Republic), and Hungary and a bilateral agreement with the Philippines under which certain of their consular personnel in the United States (and sometimes their families) obtain significantly higher privileges and immunities, in some cases approximating those afforded diplomatic agents. These arrangements are not uniform, so law enforcement officers will have to be governed by the official identity documents which have been issued by the Department of State to such personnel.

6 Police officers should note this distinction carefully. In connection with other categories discussed in this booklet, either a person is absolutely protected from arrest or, alternatively, he or she has no immunity from arrest what-soever. In the case of career consular officers, such arrest may be carried out only if the police officer is operating under the authority of a warrant or similar judicial authorization. Note, however, the discussion below of the public safety prerogatives of police authorities.

7 All foreign personnel assigned to official duty at bilateral diplomatic or consular missions in the U.S. would have A-category visas. G-category visas are the equivalent, which are issued to foreigners assigned to duty at an international organization in the U.S. or at a foreign country's mission to such organization.

1 This table presents general rules. Particularly in the cases indicated, the employees of certain foreign countries may enjoy higher levels of privileges and immunities on the basis of special bilateral agreements.

2 Reasonable constraints, however, may be applied in emergency circumatances involving self-defense, public safety, or the prevention of serious criminal acts.

3 A small number of senior officers are entitled to be treated identically to ‘diplomatic agents.”

4 Note that consular residences are sometimes located within the official consular premises. In such cases, only the official office space is protected from police entry.