Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 May 2017

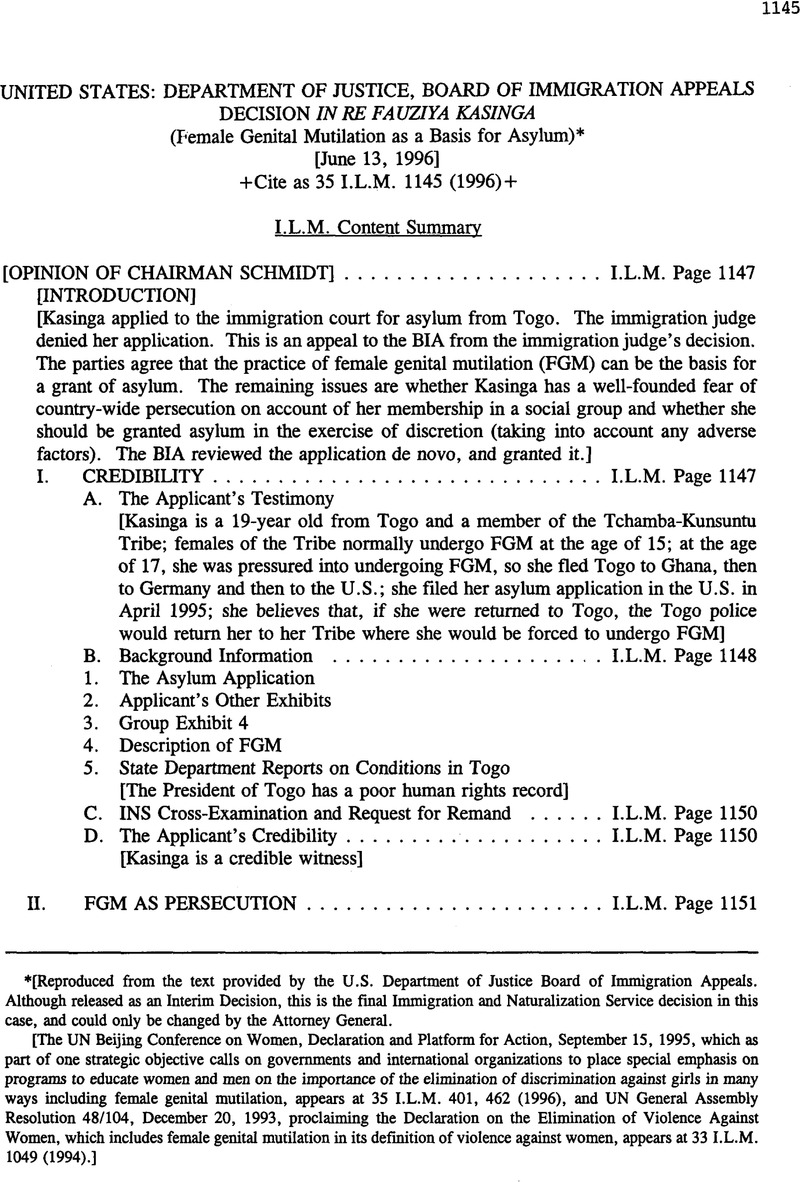

Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Department of Justice Board of Immigration Appeals. Although released as an Interim Decision, this is the final Immigration and Naturalization Service decision in this case, and could only be changed by the Attorney General.

[The UN Beijing Conference on Women, Declaration and Platform for Action, September 15, 1995, which as part of one strategic objective calls on governments and international organizations to place special emphasis on programs to educate women and men on the importance of the elimination of discrimination against girls in many ways including female genital mutilation, appears at 35 I.L.M. 401, 462 (1996), and UN General Assembly Resolution 48/104, December 20, 1993, proclaiming the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women, which includes female genital mutilation in its definition of violence against women, appears at 33 I.L.M. 1049 (1994).]

1 Although not before us, the applicant's detention obviously had an impact on the trial and presentation of this case. The INS General Counsel characterizes the applicant's case as a “venture into new and difficult territory” of great importance (INS Reply Brief at 12). In light of that characterization, the applicant's young age, and her lack of any known criminal record, it is not apparent how the resolution of such important issues was facilitated by the applicant's long-term detention. The Commissioner and the General Counsel might well wish to review this policy should future cases of this type arise.

1 This is not to say we are bound absolutely by the parties’ arguments. But we face here an issue of first impression, in relation to FGM claims, and we lack the benefit of either amicus briefing or supplemental briefing on questions we might pose. In the absence of any dispute of consequence between the parties, there is no need to resolve this particular question in order to decide the case.

2 It might also be anomalous if persons facing death in their homelands because of religious or political persecution were denied protection for having “assisted, or otherwise participated in the persecution”of their children simply by virtue of being parents of FGM victims and having followed tribal custom. See section 243(h)(2)(A) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. § 1253(h)(2)(A); 8 C.F.R. § 208.13(c).

3 But for the concession of the Service on this point, I would be inclined to remand this case for further development on the “social group” question. The meaning of the phrase “membership in a particular social group” has not been completely explained by our case law. Nevertheless, it is questionable whether the statute was meant to encompass groups that are defined principally in relation to the harm feared by the asylum applicant. See Bastanipour v. INS. 980 F.2d 1129, 1132 (7th Cir. 1992); Gomez v. INS. 947 F.2d 660, 663-64 (2d Cir. 1991). The record here sheds little light on this question.

4 Indeed, appropriate new legislation might prove to be the better answer if principles of asylum law in fact end up creating the types of anomalies identified by the Service.