No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

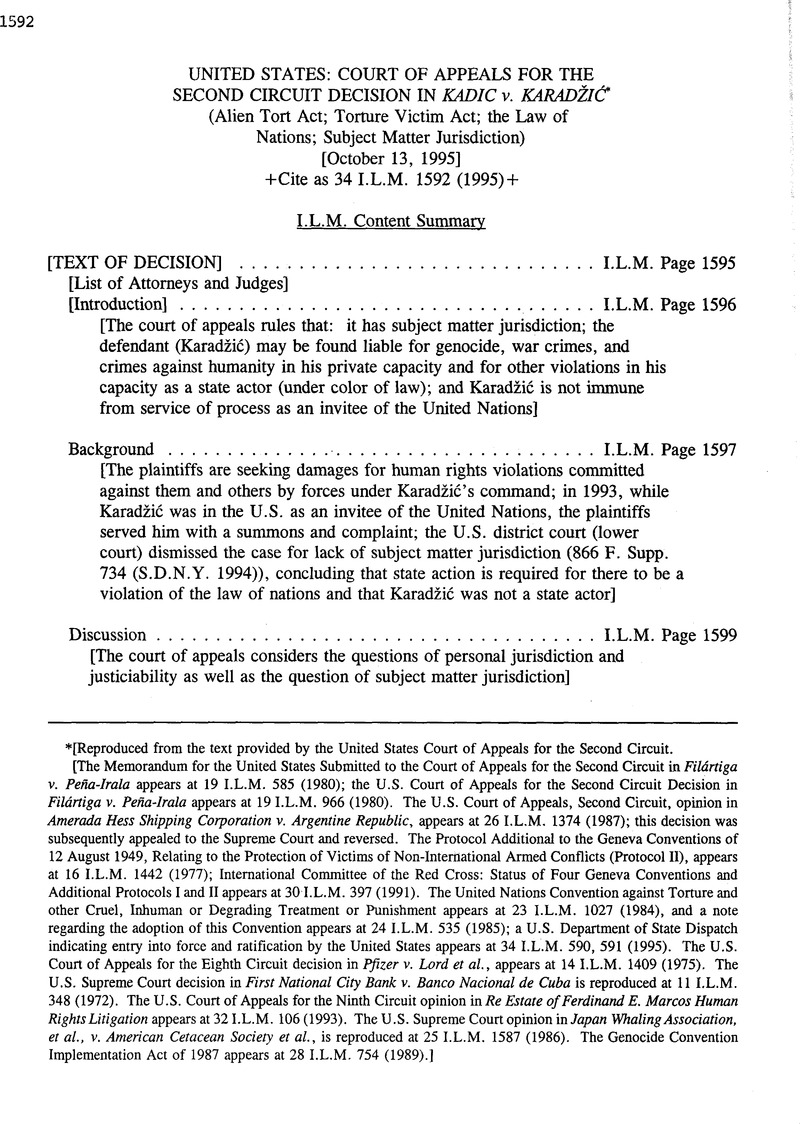

[Reproduced from the text provided by the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

[The Memorandum for the United States Submitted to the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in Filártiga v. Pena-Irala appears at 19 I.L.M. 585 (1980); the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Decision in Filártiga v. Peña-Irala appears at 19 I.L.M. 966 (1980). The U.S. Court of Appeals, Second Circuit, opinion in Amerada Hess Shipping Corporation v. Argentine Republic, appears at 26 I.L.M. 1374 (1987); this decision was subsequently appealed to the Supreme Court and reversed. The Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, Relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts (Protocol II), appears at 16 I.L.M. 1442 (1977); International Committee of the Red Cross: Status of Four Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocols I and II appears at 30 I.L.M. 397 (1991). The United Nations Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment appears at 23 I.L.M. 1027 (1984), and a note regarding the adoption of this Convention appears at 24 I.L.M. 535 (1985); a U.S. Department of State Dispatch indicating entry into force and ratification by the United States appears at 34 I.L.M. 590, 591 (1995). The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit decision in Pfizer v. Lord et al., appears at 14 I.L.M. 1409 (1975). The U.S. Supreme Court decision in First National City Bank v. Banco Nacional de Cuba is reproduced at 11 I.L.M. 348 (1972). The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit opinion in Re Estate of Ferdinand E. Marcos Human Rights Litigation appears at 32 I.L.M. 106 (1993). The U.S. Supreme Court opinion in Japan Whaling Association, et al., v. American Cetacean Society et al., is reproduced at 25 I.L.M. 1587 (1986). The Genocide Convention Implementation Act of 1987 appears at 28 I.L.M. 754 (1989).]

1 Filàrtiga did not consider the alternative prong of the Alien Tort Act: suits by aliens for a tort committed in violation of “a treaty of the United States.” See id. at 880. As in Filàrtiga, plaintiffs in the instant cases “primarily rely upon treaties and other international instruments as evidence of an emerging norm of customary international law, rather th[a]n independent sources of law,” id. at 880 n.7.

2 Two passages of the District Court's opinion arguably indicate that Judge Leisure found the pleading of a violation of the law of nations inadequate because Srpska, even if a state, is not a state “recognized” by other nations. “The current Bosnian-Serb warring military faction does not constitute a recognized state …. “Doe, 866 F. Supp. at 741; “[t]he Bosnian-Serbs have achieved neither the level of organization nor the recognition that was attained by the PLO [in Tel-Oren v. Libyan Arab Republic, 726 F.2d 774 (D.C. Cir. 1984)],” id. However, the opinion, read as a whole, makes clear that the Judge believed that Srpska is not a state and was not relying on lack of recognition by other states. See, e.g., id. at 741 n.12 (“The Second Circuit has limited the definition of ‘state’ to ‘entities that have a defined [territory] and a permanent population, that are under the control of their own government, and that engage in or have the capacity to engage in, formal relations with other entities.’ Klinghoffer v. S.N.C. Achille Lauro, 937 F.2d 44,47 (2d Cir. 1991) (quotation, brackets and citation omitted). The current Bosnian-Serb entity fails to meet this definition.” We quote Judge.

3 Section 702 provides:

A state violates international law if, as a matter of state policy, it practices, encourages, or condones

(a)genocide,

(b)slavery or slave trade,

(c)the murder or causing the disappearance of individuals,

(d)torture or other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or pun ishment,

(e)prolonged arbitrary detention,

(f) systematic racial discrimination, or

(g) a consistent pattern of gross violations of internationally recognized human rights.

4 Section 404 provides: A state has jurisdiction to define and prescribe punishment for certain offenses recognized by the community of nations as of universal concern, such as piracy, slave trade, attacks on or hijacking of aircraft, genocide, war crimes, and perhaps certain acts of terrorism, even where [no other basis of jurisdiction] is present.

5 Judge Edwards was the only member of the Tel-Oren panel to confront the issue whether the law of nations applies to non-state actors. Then Judge Bork, relying on separation of powers principles, concluded, in disagreement with Fildrtiga, that the Alien Tort Act did not apply to most violations of the law of nations. Tel-Oren, 726 F.2d at 798. Judge Robb concluded that the controversy was non-justiciable. Id. at 823.

6 The Senate Report merely repeats the language of section 1092 and does not provide any explanation of its purpose. See S. Rep. 333, 100th Cong., 2d Sess., at 5 (1988), reprinted at 1988 U.S.C.C.A.N. 4156,4160. The House Report explains that section 1092 “clarifies that the bill creates no new federal cause of action in civil proceedings.” H.R. Rep. 566, 100th Cong., 2d Sess., at 8 (1988) (emphasis added). This explanation confirms our view that the Genocide Convention Implementation Act was not intended to abrogate civil causes of action that might be available under existing laws, such as the Alien Tort Act.

7 Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field, entered into force Oct. 21,1950, for the United States Feb. 2, 1956, 6 U.S.T. 3114, T.I.A.S. 3362, 75 U.N.T.S. 31 (hereinafter “Geneva Convention I“); Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded, Sick, and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea, entered into force Oct. 21, 1950, for the United States Feb. 2, 1956, 6 U.S.T. 3217, T.I.A.S. 3363, 75 U.N.T.S. 85; Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, entered into force Oct. 21, 1950, for the United States Feb. 2, 1956, 6 U.T.S. 3316, T.I.A.S. 3364, 75 U.N.T.S. 135; Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, entered into force Oct. 21, 1950, for the United States Feb. 2, 1956, 6 U.S.T. 3516, T.I.A.S. 3365, 75 U.N.T.S. 287.

8 Appellants also maintain that the forces under Karadzic's command are bound by the Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, Relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-Interna¬tional Armed Conflicts, 161.L.M. 1442 (1977) (“Protocol II“), which has been signed but not ratified by the United States, see International Committee of the Red Cross: Status of Four Geneva Conventions and Addi-tional Protocols I and II, 301.L.M. 397 (1991). Protocol II supplements the fundamental requirements of common article 3 for armed conflicts that “take place in the territory of a High Contracting Party between its armed forces and dissident armed forces or other organized armed groups which, under responsible command, exercise such control over a part of its territory as to enable them to carry out sustained and concerted military operations and to implement this Protocol.” Id. art. 1. In addition, plaintiffs argue that the forces under Karadzic's command are bound by the remaining provisions of the Geneva Conventions, which govern international conflicts, see Geneva Convention I art. 2, because the self-proclaimed Bosnian-Serb republic is a nation that is at war with Bosnia-Herzegovina or, alternatively, the Bosnian-Serbs are an insurgent group in a civil war who have attained the status of “belligerents,” and to whom the rules governing international wars therefore apply. At this stage in the proceedings, however, it is unnecessary for us to decide whether the requirements of Protocol II have ripened intouniversally accepted norms of international law, or whether the provi¬sions of the Geneva Conventions applicable to international conflicts apply to the Bosnian-Serb forces on either theory advanced by plaintiffs. Act was not intended to abrogate civil causes of action that might be available under existing laws, such as the Alien Tort Act.

9 Conceivably, a narrow immunity from service of process might exist under section 11 for invitees who are in direct transit between an airport (or other point of entry into the United States) and the Headquarters District. Even if such a narrow immunity did exist—which we do not decide—Karadzic would not benefit from it since he was not served while traveling to or from the Headquarters District.

10 The Habib letter on behalf of the State Department added: We share your repulsion at the sexual assaults and other war crimes that have been reported as part of the policy of ethnic cleansing in Bosnia-Herzegovina. The United States has reported rape and other grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions to the United Nations. This information is being investigated by a United Nations Commission of Experts, which was established at U.S. initiative.