No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

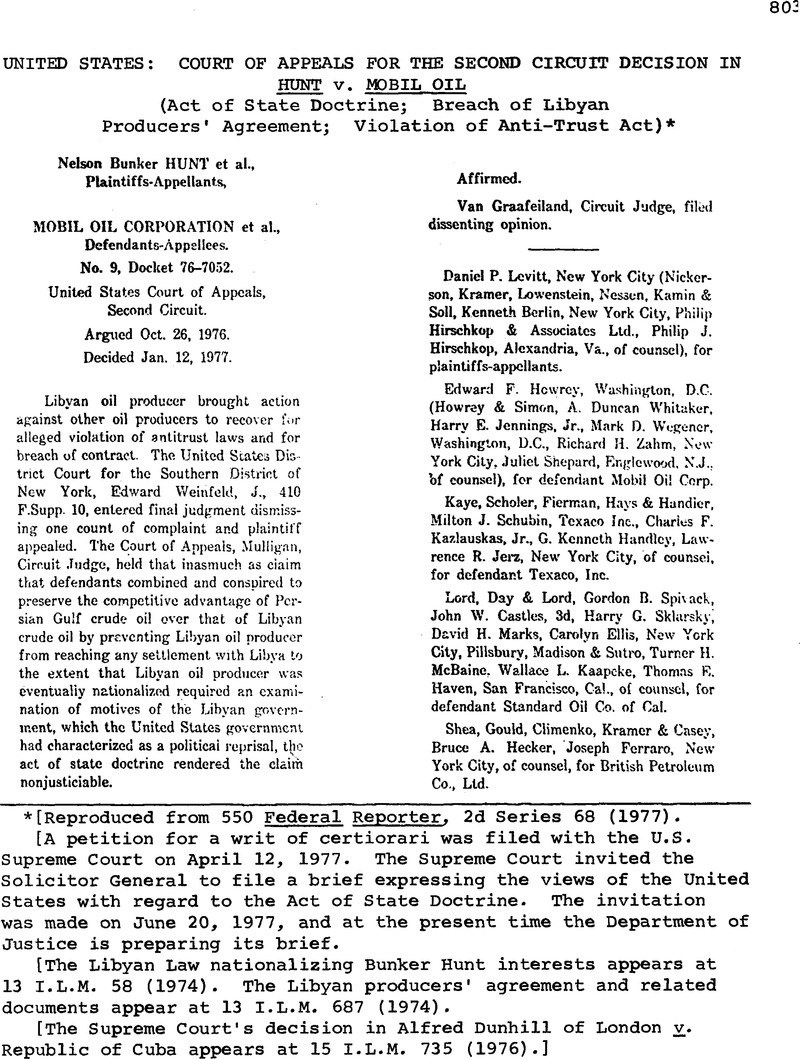

[Reproduced from 550 Federal Reporter, 2d Series 68 (1977).

[A petition for a writ of certiorari was filed with the U.S. Supreme Court on April 12, 1977. The Supreme Court invited the Solicitor General to file a brief expressing the views of the United States with regard to the Act of State Doctrine. The invitation was made on June 20, 1977, and at the present time the Department of Justice is preparing its brief.

[The Libyan Law nationalizing Bunker Hunt interests appears at 13 I.L.M. 58 (1974). The Libyan producers’ agreement and related documents appear at 13 I.L.M. 687 (1974).

[The Supreme Court's decision in Alfred Dunhill of London v. Republic of Cuba appears at 15 I.L.M. 735 (1976).]

* Of the Southern District of New York, sitting by designation.

1 The seven major oil producer defendants are Mobil Oil Corporation, Exxon Corporation, Shell Petroleum Corporation, Ltd., Texaco, Inc., Standard Oil Company of California, The British Petroleum Company, Ltd. and Gulf Oil Corporation. They explore for, produce and refine crude oil, transport both crude oil and refined petroleum products and market refined petroleum products. The bulk of their crude oil production (about 90%) is in the Persian Gulf area (Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait. Abu Dhabi, Qatar, Dubai and Oman). Gulf has no Libyan production. Defendants Occidental, Gelsenberg and Grace are diversified companies producing crude oil in Libya.

2 Third Claim

61. Plaintiff Hunt realleges each and every allegation contained in paragraphs 1 through 45.

62. Since at least 1970, the seven majors along with co-conspirators named and not named, have engaged in a combination and/or conspiracy in unreasonable restraint of the foreign trade and commerce of the United States, in violation of the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1, and of Section 73 of the Wilson Tariff Act, 15 U.S.C. § 8.

63. As part of the unlawful conduct complained of, the seven majors have combined and conspired among themselves to preserve the competitive advantage of Persian Gulf crude oil relative to that of Libyan crude oil, and to diminish competition from Libyan crude oil producers. To these ends they have combined and conspired to prevent plaintiff Hunt and other Libyan producers from reaching any agreement with the Libyan government inconsistent with that competitive advantage, even where they knew that the necessary and foreseeable consequence of their conduct would be Hunt’s elimination as a Libyan crude uil producer.

64. In furtherance of this unlawful combination and conspiracy, the seven majors entered into written agreements with Hunt and other Libyan producers, manipulated the course of Libyan negotiations so as to advance their own interests in the Persian Gulf, and followed a course of action that led to Hunt’s nationalization and elimination from the production of Libyan crude oil.

65. By reason of this unlawful combination and conspiracy. Hunt has been and will continue to be injured in his business and property. He has sustained damages, the full extent of which cannot presently be calculated, but which include lost profits on his half interest in the 11 billion barrels of crude oil contained in the Sarir Field.

3 The dissenting opinion of Mr. Justice Marshall with whom Justices Brennan, Stewart and Blackmun joined would have held the acts complained of within the proscription of the act of state doctrine. 96 S.Ct. at 1871.

4 Statement of the State Department, Hearings before the Subcomm. on Multinational Corporations of the Senate Comm. on Foreign Relations, 93rd Cong., 2d Sess., pt. 6, at 316 17 (1974). The commentary that accompanied Libya’s Law 42 of 1973 that effectuated the seizure described the act as “a warning to the United States to end its recklessness and hostility to the Arab nation.” It further stated that. “In view of . . . American impudence and the continued disregard for Arab rights and destinies, it was necessary to strike a blow against U.S. policy. . .” A. Rovine, Digest of United States Practice in International Law 1973 at 334.

5 A. Rovine, Digest of United States Practice in International Law 1973 at 335.

6 Appellants argue that Mr. Justice Holmes had a uniquely narrow view of the Sherman Act. His disaffection for that legislation needs little documentation. E. g.. Letter from Justice Holmes to Harold J. Laski. March 4, 1920, in 1 Holmes-Laski Letters 248-49 (1953 ed. M. Howe). However, the comment is not really germane. The unanimous opinion of the Court is hardly suspect because of the possible animus of its author. In any event, as we shall develop, the antitrust and act of state elements of the decision are distinct.

7 Most commentators have also concluded that American Banana’s precedential value on the act of state doctrine was undiminished by Sisni 01 any other case cited for that proposition by appellants. E.,g., A.B.A., Antitrust Developments 365 (1975); K. Brewster. Antitrust and American Business Abroad 97 (1958); W. Fugate, Foreign Commerce and the Antitrust Laws § 2.21 (1973).

8 Appellants also contend that American Banana is inapplicable because Hunt relies on not only the Sherman Act but also the Wilson Tariff Act which “was not in existence when American Banana was decided.” Since the antitrust provision of the Wilson Tariff Act was , initially enacted in 1894. Act of Aug. 27, 1894, c. 349, § 73, 28 Stat. 570, in substantially the same language as appears presently. 15 U.S.C. § 8, the argument is fallacious. In any event, this argument only relates to jurisdiction and does not affect the act of state issue. In so far as the substantive antitrust provisions of the Wilson Tariff Act are concerned, they follow the same pattern as the Sherman Act. United States v. Cooper Corp., 312 U.S. 600, 608. 61 S.Ct. 742, 85 L.Ed. 1071 (1941); see W. Fugate, Foreign Commerce and the Antitrust Laws § 13.2 (2d ed. 1973).

9 Occidental in fact supports the holding below and the discussion here on the vitality of American Banana. Thus the court, while recognizing that the restrictive view of Mr. Justice Holmes in American Banana as to the territorial reach of the Sherman Act has not survived subsequent Supreme Court holdings, found that the act of state holding there applied has endured unscathed. 331 F.Supp. at 109-10.

10 ¶¶ 34, 40, 41 of the complaint.

11 Appellants urge on appeal that the interpretation of the third claim below was unduly narrow since ¶ 63 of the complaint, supra, note 2, also charged that the defendants conspired to preserve the competitive advantage of Persian Gulf crude oil over that of Libyan and thus to diminish competition by preventing Hunt from reaching any agreement with the Libyan government inconsistent with that advantage. However, Hunt’s first claim which alleges a conspiracy among the defendants in violation of both the Sherman and Wilson Tariff Acts states in ¶ 50(b) of the complaint that the major producers took steps to restrain competition by, “Negotiation and administration of the Libyan Producers’ Agreement so as to disadvantage Libyan oil relative to Persian Gulf oil.” That claim was not dismissed and Hunt is therefore not precluded from raising the issue at trial. Judge Weinfeld specifically found the act of state doctrine unavailable to the defendants on this count. 410 F.Supp. at 20-21.

12 The importance of a unified national voice on foreign policy has been recognized since the founding of the republic. See The Federalist No. 42 (J. Madison). The judiciary, even when it has had jurisdiction, has traditionally been reluctant to infringe on the executive’s authority in the area of foreign affairs. This has resulted in the application of the political question doctrine to find such issues non-justiciable. See Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186, 211-13. 82 S.Ct. 691, 7 L.Ed.2d 663 (1962).

13 See Holtzman v. Schlesmger, 484 F.2d 1307, 1310-11 (2d Cir. 1973), cert. denied. 416 U.S. 936, 94 S.Ct. 1935, 40 L.Ed.2d 286 (1974), and Mitchell v. Laird, 159 U.S.App.D.C. 344, 488 F.2d 611, 616 (1973), which emphasize the difficulty of a judicial tribunal in making determinations of political and diplomatic dimensions in the arena of foreign affairs, an area entrusted to the discretion of the President and the Department of State.

14 Our dissenting brother parts company with us when we say that in order to prove their damages, plaintiffs will be required to establish the motivation for the Libyan expropriation and that this inevitably involves its validity. He further argues that Libya is shielded from antitrust liability. We agree that Libya cannot be guilty of a Sherman Act violation. This is certainly so here since it is not a party and, in any event, it could not be because it is not a person or corporation within the terms of the Act but a sovereign state, intcramerican Refining Corp. v. Texaco Maracaibo, Inc., 307 F.Supp. 1291, 1298 (D.Del. 1970); Fugate, Antitrust Jurisdiction and Foreign Sovereignty, 49 Va.L.Rev. 925, 932 (1962); K. Brewster. Antitrust and American Business Abroad 94 (1958). (There is no claim here that Libya was performing a purely commercial act.) When we have discussed the “validity” of the act of confiscation we are not using the term in an antitrust sense but rather in an international law context. The plaintiffs admittedly can only succeed if they establish the motivation of Libya in making the seizure. The United States has characterized it as an act of political reprisal. We are now asked to determine that Libya would not have so acted had it not been for the conspiracy of the defendants. As recently indicated in Timberlane Lumber Co. v. Bank of America, 549 F.2d 597 (9th Cir. 1976), “We wish to avoid ‘passing on the validity’ of foreign acts. Sabbatino, 376 U.S. at 423, [84 S.Ct. 923]. Similarly, we do not wish to challenge the sovereignty of another nation, the wisdom of its policy, or the integrity and motivation of its action.” See The Restatement, Second, Foreign Relations Law of the United States, § 41 (1965), “[A] court in the United States . . . will refrain from examining the validity of an act of a foreign state by which that state has exercised its jurisdiction to give effect to its public interests.”

The dissent also urges that Libya’s authorization, approval, encouragement or participation in restrictive private conduct confers no antitrust immunity on the wrongdoer. But this is not a case of Libyan participation in antitrust wrongdoing. The complaint is rather thru Libya like Hunt was a “victim” of the conspiracy.