No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

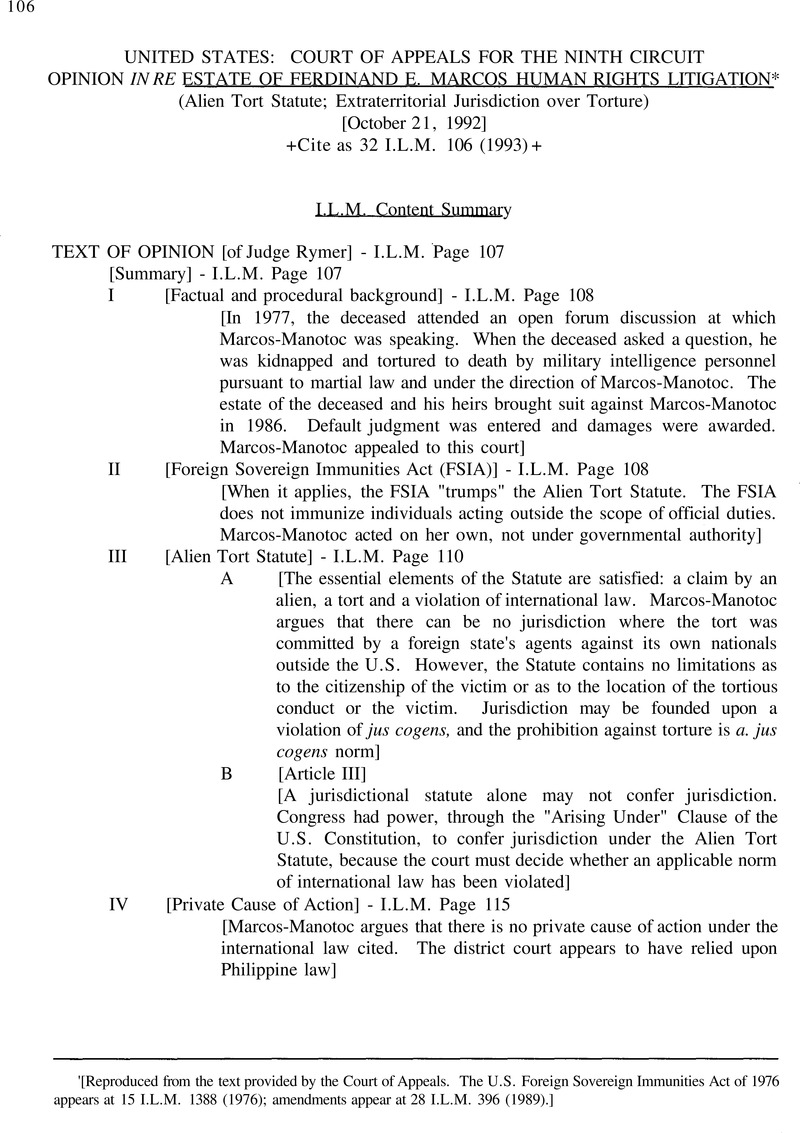

* '[Reproduced from the text provided by the Court of Appeals. The U.S. Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976 appears at 15 I.L.M. 1388 (1976); amendments appear at 28 I.L.M. 396 (1989).]

'This appeal pertains only to the action against Marcos-Manotoc. Several amici appear in support of Trajano: the Allard K. towenstcin International Human Rights Clinic, the Center for Constitutional Rights, and Human Righls Watch. The United States filed a brief as amicus curiae in connection with an earlier appeal from an order dismissing the action against Ferdinand Marcos on act of State grounds; the brief covers the issues raised in Marcos-Manotoc's appeal and we have considered it as well.

'Marcos-Manotoc also argues that the action is lime-barred by the two-year Hawaii statute of limitations. Haw. Rev. Stal. § 657-7, but this is an affirmative defense which was waived by virtue of her default. Because the statute of limitations is not jurisdictional, we do nol consider this issue. See United States v. DeTar, 832 F.2d 1110, 1114 (9th Cir. 1987). In her reply brief, Marcos-Manotoc claims that the district court did not have personal jurisdiction over her because she was not properly served. The district court found to the contrary. Because this issue was raised for the first time in her reply brief, Marcos-Manotoc has waived this issue as well. See Nevada v. Waikins, 914 F.2d 1545, 1560 (9th Cir. 1990), cen. denied. 111 S. Ct. 1105(1991).

3 M;ircos moved to dismiss on act of state grounds, and the district court's order granting that motion was reversed on appeal in light of our intervening decision in Republic of the Philippines v. Marcos, 862 F.2d 1355, 1360-61 (9th Cir. 1988) (en bane) (civil RICO action brought by the Philippines against Marcos not barred by act of state doctrine), cert, denied, 490 U.S. 1035 (1989). See Trajano v.Marcos,No. 86-2448 (9th Cir. July 10. 1989). The Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation then consolidated two other actions against Marcos in the District of Hawaii and two actions in the Northern District of California, and assigned them to the Honorable Manuel L. Real, silling pursuant to an intracircuit assignment under 28 U.S.C. § 292(b). The four actions consolidated with Trajano's are not before us at this time.

'The district court awarded the estate of Archimedes Trajano $236,000 for tost earnings pursuant to Article 2206( I ) of the Philippine Civil Code; $175,000 for moral damages including physical suffering, mental anguish, fright, bodily injury, and wrongful death pursuant to Articles 2217, 2204, and 2206 of the Philippine Civil Code; awarded Agapita Trajano $1,250,000 for mental anguish pursuant to Article 2206(3) of the Philippine Civil Code; and awarded both Mrs. Trajano and the estate $2,500,000 in punitive damages pursuant to Articles 2229 and 2231 of the Philippine Civil Code, as well as $246,966.99 in costs and attorneys’ fees pursuant to Article 2208(1), (5), (9) and (11) of the Code.

*

28 U.S.C. § 1603(b) defines an “agency or instrumentality of a foreign state” as any entity:

(1) which is a separate legal person, corporate or otherwise, and

(2) which is an organ of a foreign state or political subdivision thereof, or a majority or whose shares or other ownership interest is owned by a foreign state or political subdivision thereof, and

(3) which is neither a citizen of a State of the United States as defined in section 1332(c) and (d) of this title, nor created under the laws of any third country.

7 The Court held that the most pertinent FSIA exception to sovereign immunity — that for noncommercial torts, § 16O5(a)(5) — did not apply because it is limited to those cases in which the damage occurs in the United Stales. 488 U.S. at 439-40.

28 U.S.C. § 1604 provides: Subject to existing international agreements to which the United States is a party at the time of enactment of this Act a foreign state shall be immune from the jurisdiction of the courts of the United States and of the States except as provided in sections 1605 to 1607 of this chapter.

Amiens urges that the FSIA docs not immunize individuals at all, see Amerada Hess, 488 U.S. at 438 (the Alien Tort Statute “of course has the same effect after the passage of the FSIA as before with respect to defendants other than foreign states“), but this argument is forectosed by Chuidian

Section 1605(a)(5) provides: (a) A foreign stale shall not be immune from (lie jurisdiction of courts of the United States or of the States in any case— (5) nol otherwise encompassed in the commercial activity exception), in which money damages are sought against a foreign state for personal injury or death, or damage to or toss of property, occurring in (lie United States and caused by the tortious act or omission of Ihat foreign state or of any official or emptoyee of that foreign stale while acting within the scope of his office or emptoyment; except this paragraph shall not apply to— (A) any claim based upon the exercise or performance or the failure to exercise or perform a discretionary function regardless of whether the discretion be abused

10 This is consistent with our earlier decision thai the same allegations against former President Marcos arc not nonjusticiable “acts of state.” See Trajano v. Marcos, No. 86-2448 (9th Cir. July 10, 1989). In so holding, we implicitly rejected the possibility that the acts set out in Trajano's complaint were public acts of the sovereign. Marcos-Manotoc presented no evidence to the contrary; indeed, her affidavit in support of the motion to lift entry of default declares that she was not a member of the government or the military at the time of Trajano's murder.

The parties also disagree about whether the Philippine government's statement of non-objection to the litigation against former President Marcos amounts to a waiver of sovereign immunity for Marcos-Manotoc. Given our view that Marcos-Manotoc was not an official entitled to immunity, it is unnecessary to reach this issue.

28 U.S.C. § 1330(a) provides: The district courts shall have original jurisdiction without regard to amount in controversy of any nonjury civil action against a foreign state as defined in section 1603(a) of this title as to any claim for relief in personam with respect to which the foreign state is not entitled to immunity either under sections 1605-1607 of this title or under any applicable international agreement. Sections 1605-1607 set out the exceptions to immunity and the extent of liability. Because Marcos-Manotoc was not acting in an official capacity, she has no claim to sovereign immunity, no exceptions are applicable, and there can be no jurisdiction under § 133O(a).

14 Judiciary Act of September 24, 1789, ch. 20. § 9, 1 Stat. 73, 76-77. The original statute read: [T]he district courts shall … have cognizance, concurrent with the courts of the several States, or the circuit courts, as the case may be, of all causes where an alien sues for a tort only in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States.

15 These include the United Nations Charter, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, G. A. Res. 217A(III), 3 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 16), U.N. Doc. A/810 (1948); the American Convention on Human Rights, Nov. 22, 1969, 36 O.A.S.T.S. 1,O.A.S. Official Records OEA/Ser. 4 v/H 23, doc 21, rev. 2 (1975); the Declaration on the Protection of All Persons From Being Subjected to Torture, G. A. Res. 3452, 30 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 34) at 91, U.N. Doc. A/1034 (1975); and the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, G.A. Res. 39/46, 39 U.N. GAOR Supp. No. 51 at 197, U.N. Doc. A/RES/39/708 (1984), reprinted in 23 I.L.M. 1027 (1984).

16 Marcos-Manotoc does not contend that the actions alleged do not give rise to tort liability for wrongful death both in the Philippines and in Hawaii. Because the case comes to us after entry of a default judgment, and she does not appeal the district court's award of damages pursuant to Philippine law, we have no call to decide issues pertaining to choice of law.

Article 14 of the 1984 Convention provides: Each State Party shall ensure in its legal system that the victim of an act or torture obtains redress and has an enforceable right to fair and adequate compensation, including the means for as full rehabilitation as possible.In the event of the death of the victim as a result of an act of torture, his dependents shall be entitled to condensation. Nothing in this article shall affect any right of the victim or other persons to compensation which may exist under national law.

“The Senate's understanding under Article 14 reads: [I]t is the understanding of the United States that Article 14 requires a State Party to provide a private right of action for damages only for acts of torture committed in territory under the jurisdiction of that State Party.

136 Cong. Rec. S17486 (daily ed. Oct. 27, 1990).

“See, e.g.. The Torture Victim Protection Act of 1991, Pub. L. No. 102-256, 106 Slat. 73 (1992) (providing federal cause of action for redress of torture and extrajudicial killing, irrespective of nationality of parties or locus of activities)

“The Foreign Diversity Clause provides that the judicial power extends “to Controversies … between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.” U.S. Const. Art. III. § 2. cl. 1.

““The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases … arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United Stales, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority.” U.S. Const. Art. III, § 2, cl. 1.

“See supra Part II.

2 *Becaiise Congress passed the Torture Victim Protection Act, supra n.I8, after the district court's decision, we have no occasion to consider its applicability to the present case.