No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

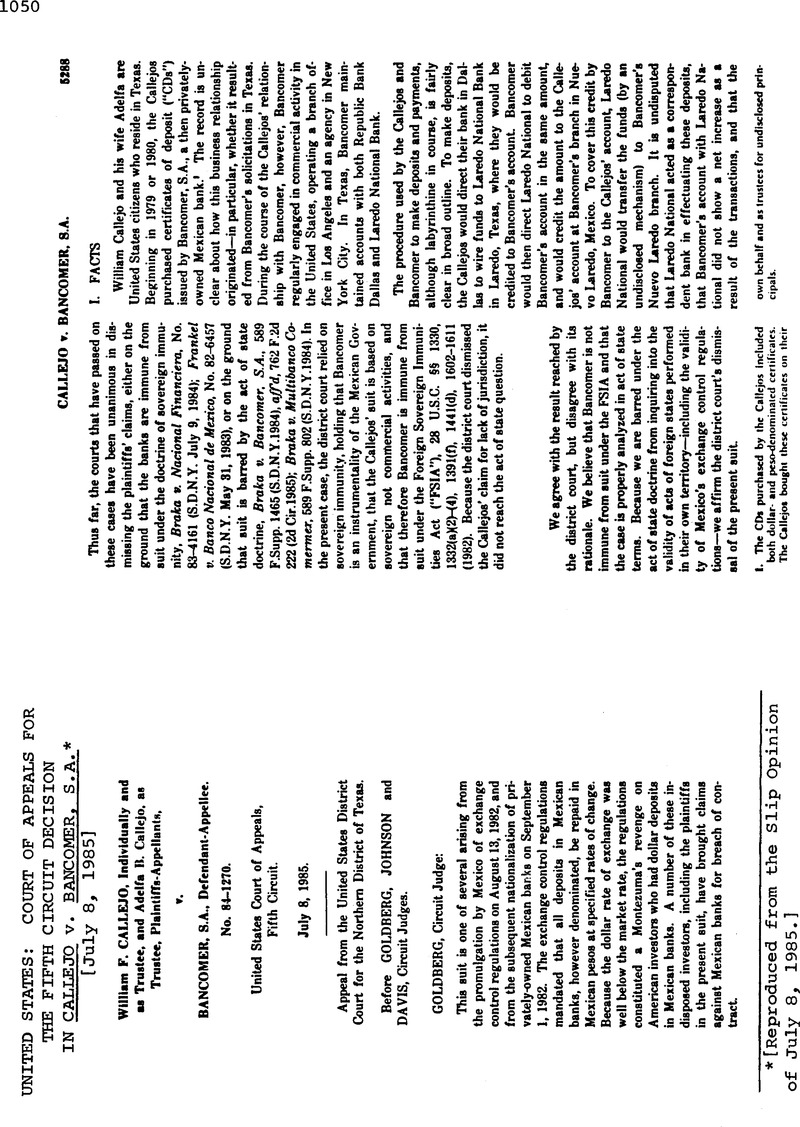

United States: Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit Decision in Callejo v. Bancomer, S.A.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Legislation and Regulations

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1985

References

* [Reproduced from the Slip Opinion of July 8, 1985.]

1 The CDs purchased by the Callejos included both dollar- and peso-denominaled certificates. The Callejos bought these certificates on their own behalf and as trustees for undisclosed principals.

2 The govcmmentally-established exchange rale was 70 pesos lo the dollar for all non-priority transactions. According to the Callejos, the market exchange rate in August 1982 was 114 pesos to the dollar. This rale subsequently rose to more than 130 pesos to the dollar in November 1982.

3 Initially, the Callejos brought this action in the 95th Judicial District Court for Dallas County, seeking money damages. On September 30, 1982, however. Bancomer removed the action, pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1441(d). to the United states District Court for the Northern District of Texas, on the ground that it was an “agency or instrumentality of a foreign state” as defined by the FSIA. 28 U.S.C. § 1603(b).

4 The Callejos claim that Bancomer's failure to register the certificates violated Section 12(1) of the Securities Act of 1933. IS U.S.C. § 77/(1) (1982) and Section 33A.1 of the Texas Securities Act, Tex.Rev.Civ.tat.Ann. art. 581-33 A.(1).

5 Under the FSIA. where an exception to sovereign immunity applies, the federal courts have subject-matter jurisdiction over the dispute. 28 U.S.C. § 1330(a); see Verlinden B.V. v. Central Bank of Nigeria, 461 VS. 480. 103 S.Ct. 1962. 76 L.Ed.2d 81 (1983) (subject-matter jurisdiction over FSIA suits does not depend on diversity of citizenship; instead. FSIA claims fall within the judicial power of the United States because they “arise under” the laws of the United States, i.e., the FSIA itself)- Moreover, where subject matter jurisdiction exists and where service of process is made pursuant to 28 U.S.C. ” 1608. then personal jurisdiction exists. 28 U.S.C. § 1330(b). As with all suits, however, the exercise of personal jurisdiction must comply with the due process clause. See Texas Trading a) Milling Corp. v. Federal Republic of Nigeria, 647 F.2d 300. 308 (2d Cir.1981). cert, denied, 454 U.S. 1148. 102 SCI. 1012, 71 LEd.2d 301 (1982).

Here, Bancomer appears to concede that, if subject matter jurisdiction exists, Ihen personal jurisdiction also exists. Although Bancomer initially claimed that the Callejos failed to serve process in compliance with 28 U.S.C. f 1608, the Callejos reserved Bancomer by delivering a summons and a copy of their complaint both to the manager of Bancomer's New York agency and to The Subdirector/General Manager of Bancomer's Los Angeles branch office. On appeal, Bancomer has not reiterated its claim that the Callejos failed to comply wilh 28 U.S.C. § 1608, nor has it raised as a separate defense the argument that the exercise of personal jurisdiction would violate due process. To the extent that Bancomer contends that there are insufficient contacts for the exercise of personal jurisdiction, see Brief for Appellee at 18 n. 12, we hold that the contacts discussed in Part 11(B) below are sufficient to satisfy the requirements of due process.

6 The FSIA provides little guidance on this issue. The only discussion occurs in 28 U.S.C. § 1603(d), which states:

A “commercial activity” means either a regular course of commercial conduct or a particular commercial transaction or act. The commercial character of an activity shall be determined by reference to the nature of the course of conduct or particular transaction or act, rather than by reference to its purpose. While this is helpful so far as it goes, it is somewhat circular, since it defines “commercial activity” in terms of “commercial conduct” and “commercial transaction” but contains no independent definition of “commercial.” Generally, however, if an activity is of a type that a private person would customarily engage in for profit, it Is clearly commercial. See Lelelier v. Republic of Chile. 748 F.2d 790, 796-97 (2d Cir.1984); International Ass'n of Machinists & Aerospace Workers v. OPEC. 649 F.2d 1354, 1357 (9th Cir. 1981). cert, denied. 454 U.S. 1163. 102 S.Ct. 1036. 71 LF.dJd 319 (1982); House Report, supra, at 6614-15.

7 This interpretation is supported by the language or S 1603(d). that “[t]he commercial character of an activity shall be determined by reference to [its] nature ... rather than by reference to its purpose.” (Emphasis added). Here, the nature of Bancomer's breach of contract was commercial even though its purpose was to comply with the sovereign decrees of the Mexican Government. Cf. Arango v. Guzman Travel Advisors Corp., 621 F.2d 1371. 1379-80 (5lh Cir. 1980) (holding that commercial activity exception applied to plaintiffs contract claim, even though suit arose as a result of Dominican Republic's sovereign decision to deny plaintiffs entry).

8 Although the facts necessary to determine that the breach had direct effects In the United States are undisputed, this is not true of the question of whether the activities on which the suit is based were “carried on in the United States.” The fact that Bancomer does business In the United States is insufficient to support a finding of jurisdiction under the first clause of § 1605(a)(2). Vencedora Oceanica Navigation v. Compagnie Nationalc Algerienne de Navigation, 730 F.2d 195. 202 (Slh Cir.1984). Instead, Bancomer's commercial activities in the United States must have a nexus with the act complained of in this lawsuit. Id. A defendant's general business activities in the forum may be sufficient to establish his “presence” for purposes of personal jurisdiction, but they are insufficient to establish the contacts necessary for the exercise of jurisdiction under the FSIA. Harris v. VAO Intourist, 481 F-Supp. 1056, 1059-61 (E.D.N.Y.I979). In the present case, it is unclear whether the acts complained of grew out of Bancomer's commercial activities within the United States. On the one hand, Bancomer utilized the services of American correspondent banks and the U.S. mails, and placed telephone calls to the Callejos in Texas regarding the purchase and renewal of the CDs. On the other hand, Bancomer does not appear to have advertised or otherwise solicited business in the United States In connection with the sale of the certificates. Cf. Wolf v. Banco National de Mexico, 739 F.2d 1458, 1460 (9th Cir.1984) (holding that where plaintiff purchased CDs as a result of defendant's advertisements in the U.S., the sale of the CDs was a commercial activity carried on in Ihe U.S.), cert, denied— U.S.—105 S.Ct. 784. 83 L.Ed.2d 778 (1985). Given the undeveloped state of the record and the fact that we need not reach this issue, we express no opinion about what activities in Ihe United States would be sufficient to satisfy the first clause of § 1605(a)(2).

9 Although we agree with the Texas Trading court that Congress's reference to § 18 is “a bil of a non sequitur” since that section relates to the extraterritorial effect of American substantive law, not to the extraterritorial jurisdictional reach of American courts, 647 F.2d at 311, we nonetheless view § 18 as evidence of Congressional intent. Accord Maritime Intl Nominees Establishment v. Republic of Guinea, 693 F.2d 1094. 1110-1111 (DCCir.1982) (applying § 18 in FSIA suit), cert, denied, VS. , 104 SCt. 71, 78 L.Ed.2d 84 (1983); Harris, 481 F.Supp. at 1063 (same).

10 In the sovereign immunity arena, we start from a premise of jurisdiction. Where jurisdiction would otherwise exist, sovereign immunity must be pleaded as an affirmative defense; it is not presumed. Venctdora Oceanica. 730 F.2d at 199; Arango v. Guzman Travel Advisors Corp. 621 F.2d 1371, 1378 (5th Cir.1980); House Report, supra, at 6616.

11 Although normally we do not consider issues not passed upon below. Singleton v. Wuiff, 428 U.S. 106. 120. 96 SCt. 2868, 2877, 49 LEd.2d 826 (1976). it is within our discretion to do so, id. at 121. 96 S.CI. at 2877; Texas v. United States. 730 F.2d 339. 358 n. 35 (5th Cir.), cert denied—US—105 S.Ct. 267, 83 LEd.2d 203 (1984). Here, Bancomer raised the act of state issue in its motion to dismiss, and the issue was fully argued by both sides before the district court and on appeal. Because resolution of the act of state issue does not depend on any disputed issues of fact, we believe that it is ripe for decision.

12 The exact relation between the sovereign immunity and act of stale doctrines has been the source of considerable controversy. Prior to Sabbatino, it was often thought that the act of state doctrine was based on the doctrine of sovereign immunity. See Oetjen v. Central Leather Co., 246 U.S. 297, 303. 38 S.Ct. 309. 311. 62 LEd. 726 (1918); Vnderhill v. Hernandez. 168 U.S. 250. 252. 18 S.Ct. 83. 84. 42 LEd. 456 (1897). Set generally Note, Rehabilitation and Exoneration of the Act of Stale Doctrine, 12 N.Y.U.U1. Int'l L. It Pol. 599, 600-10 (1980) (early history of doctrine). Sabbatino, however, rejected this notion, grounding the act of stale doctrine in prudential rather than jurisdictional terms. 376 U.S. at 421-23, 438. 84 S.Ct. at 936-38. 945; see also Restatement (Second) of Foreign Relations Law of the United States § 41 comment e, at 128-29 (1965). But cf. Alfred Dunhill of London, Inc. v. Republic of Cuba. 425 VS. 682. 705 n. 18. 96 S.CI. 1854. 1866 n. 18. 48 L.Ed 2d 301 (1976) (plurality opinion). Consequently, passage of the FSIA has not superseded the act of stale doctrine. International Ass'n of Machinists A Aerospace Workers v. OPEC. 649 F.2d 1354, 1359 (9th Cir. 1981), cert, denied. 454 U.S. 1163, 102 S.CI. 1036. 71 L.Ed 2d 319(1982).

13 Although the act of state doctrine is nol prescribed by international law, Sabbatino, 376 U.S. al 421-22, 84 S.Ct. al 937, most other nations have shown a similar solicitude for the feelings of their fellow stales. See Restatement (Revised) of Foreign Relations Law of the United Stales § 469 reporters' note 12 (Tent. Draft No. 6, I98S).

14 The act of state doctrine rests in part on separation of power principles. “It is ... buttressed by judicial deference to the exclusive power of the Executive over conduct of relations with other sovereign powers and the power of the Senate to advise and consent on the making of treaties.” First Nat'l City Bank, 406 U.S. at 76S. 92 S.Ct. al 1812. “(1)is continuing vitality depends on its capacity to reflect the proper distribution of functions between the judicial and political branches of the Government on mailers bearing upon foreign affairs.” Sabbatino, 376 U.S. al 427-28. 84 S.Ct. al 940. However, although the doctrine has “constitutional underpinnings,” in Sabbatino the Court held that it is not required by the Constitution. Id. al 423. 84 S.Cl. al 938; cf. Occidental of Umm al Qaywayn, 577 F.2d at 1200 n. 4 (better view is that doctrine constitutionally compelled). This has produced a continuing controversy concerning whether Ihe doctrine can be waived by the executive branch or is mandatory. Compare First Nat'l City Bank. 406 U.S. at 767-769, 92 S.Ct. at 1813-14 (plurality opinion) (applying Bernstein exception, under which ad of stale doctrine does not apply when executive states that application of the doctrine would not advance the interests of American foreign policy) with id at 787-89, 92 S.Ct. al 1823-24 (Brennan, J., dissenting) (interpreting act of state doctrine in terms of nonjusticiabillty, under which validity of act of foreign state is political question). We need nol decide here which of these conflicting interpretations to follow—the Interpretation based on judicial deference or on judicial incompetence—since the executive has not expressed any desire in this case that the act of stale doctrine not be applied.

15 Only four judges joined In this part of the Court's opinion. The majority decided the case on the ground that Cuba's actions in repudiating a commercial debt were not invested with the sovereign authority of the state and hence were not acts of state at all. Id at 694-95, 96 S.Ct. al 1861. As the Court noted, “No statute, decree, order, or resolution of the Cuban Government itself was offered in evidence indicating that Cuba had repudiated its obligations in general or any class thereof or that it had as a sovereign mailer determined to confiscate the amounts due three foreign importers.” Id at 695, 96 S.Ct. at 1861. Here, there is no question that Mexico's promulgation of the exchange control regulations was invested with Ihe sovereign authority of the state. The decrees announcing the imposition of the controls were issued by the Mexican Ministry of Treasury and Public Credit and by( President Lopez Portillo, and were later reiterated in legislative enactments.

16 Writing for the plurality. Justice White justified the commercial activity exception by slating. “(Subjecting foreign governments to the rule of law in their commercial dealings presents a much smaller risk of affronting their sovereignty than would an attempt to pass on the legality of their governmental acts. In their commercial capacities, foreign governments do not exercise powers peculiar to sovereigns. Instead, they exercise only those powers that can also be exercised by private persons. Subjecting them In connection with such acts to the same rules of law that apply to private citizens Is unlikely to touch very sharply on ‘national nerves.’” Id at 703-04, 96 S.Cl. at 1866.

17 The articulation in Dunhill of a commercial activity exception to the act of state doctrine has engendered considerable debate. Compart International Association of Machinists A Aerospace Workers v. OPEC, 649 F.2d 1354. 1360 (9th Cir.1981) (declining to adopt commercial activity exception), cert, denied, 454 U.S. 1163, 102 SCt. 1036, 71 L.Ed.2d 319 (1982) with Note, Foreign Sovereign Immunity and Commercial Activity, 83 Colum.L.Rev. 1440. 1445-51 (1983) (arguing in favor of commercial activity exception).

Although we have cited Dunhill on a number of occasions, see Compania de Gas de Nuevo Undo v. Enlex, Inc., 686 F.2d 322, 326 (5th Cir.1982). cert, denied 460 U.S. 1041. 103 S.Ct. 1435. 75 LEd 2d 794 (1983); Arango v. Guzman Travel Advisors Corp., 621 F.2d 1371, 1380 n. II (5lh Cir.1980); Industrial Inv. Dev. Corp. v. Mitsui A Co.. 594 F.2d 48, 52 (5lh Cir.1979). cert, denied 445 U.S. 903. 100 S.Ct. 1078. 63 L.Ed 2d 318 (1980), thus far we have not actually adopted the commercial activity exception, Airline Pilots Ass'n v. Taca Intl Airlines, 748 F.2d 965. 970 n. 2 (5th Cir.1984), cert, denied—U.S.—105 SCt. 2324. 85 L.Ed.2d — (1985). In Entex, we held that the actions in question were governmental rather than commercial, and thus never had the opportunity to determine whether, if they were commercial, Ihe act of state doctrine would apply. 686 F.2d at 326. Similarly, we held in Mitsui that the act of state doctrine did not apply for other reasons and thus did not reach the commercial activity exception issue. 594 F.2d at 52. Finally, in Arango, the commercial activities in question were not invested with the sovereign authority of the state; they consisted merely of the sale of airline tickets and tourist cards, and the activities in connection there with. 621 F.2d at 1380 n. 11.

18 Although the Court statedin a footnote that “[t]here are of course, ares of international in which consensus as to standards is greater and which do not represent a battleground for conflicting ideologies,” and went on to state that “(t)his decision in no way intimates that the courts of this country are broadly foreclosed from considering questions of international law.” Id. at 430 n. 34. 84 S.Ct. at 941 n. 34. to our knowledge this caveat has never been pursued. We are unaware of any cases since Sabbatino that have construed customary international law to invalidate a foreign act of state. See Restatement (Revised), supra note 13, at 5 469 comment b.

19 The term, “current international transactions” is defined in Article XXX(d) of the Fund Agreement, which states in pertinent part:

(d) Payments for current transactions means payments which are not for the purpose of transferring capital, and includes, without limitation:

(1) all payments due in connection with foreign trade, other current business, including services, and normal short-term banking and credit facilities;

(2) payments due as interest on loans and as net income from other investments; The Fund may, after consultation with the members concerned, determine whether specific transactions are to be considered current transactions or capital transactions.

20 The Callejos also argue for the first time on appeal that the exchange regulations violate Art. VIII, § 3 of the Fund Agreement. Generally, we do not consider issues that were not raised before the district court unless our failure to do so would result in grave injustice, Masai v. United states. 745 F.2d 985, 988 (5th Cir.1984). or unless the issue can be resolved as a matter of law or is otherwise beyond doubt, Texas v. United States, 730 F.2d 339. 358 n. 35 (5th Cir.). cerr. denied.—U.S.—.105 SO. 267, 83 L.Ed.2d 203 (1984). Here, the Callejos' failure to raise the Art. VIII, § 3 issue has prejudiced Bancomer by precluding it from obtaining evidence from the IMF that the exchange regulations do not violate that provision. Therefore, we decline to consider this argument.

21 Apart from the Fund Agreement, the Mexican exchange control regulations appear to be permissible under international law. The Restatement (Second), supra note 12, approves such measures when “reasonably necessary ... to protect the foreign exchange resources of the state,” and notes, “[T]he application to an alien of a requirement that foreign funds held within the territory of the stale be surrendered against payment in local currency at the official rale of exchange is not wrongful under international law, even though the currency is less valuable on the free market than the foreign funds surrendered.” Id at § 198 tt comment b; see also 8 M. Whiteman, Digest of International Law 981-82, 988-90 (1967). “This is not an era ... in which there is anything novel or internationally reprehensible about even the most stringent regulation of national currencies and the flow of foreign exchange. Such practices have been followed, as the exigencies of international economics have required—and despite resulting losses to individuals—by capitalist countries and communist countries alike, by the United States and its allies as well as by those with whom our country has had profound differences. They are practices which are not even of recent origin but which have been recognized as a normal measure of government for hundreds of years, if not, indeed, as long as currency has been used as the medium of international exchange.” French v. Banco National de Cuba, 23 N.Y.2d 46, 63, 295 N.Y.S.2d 433. 242 N.B.2d 704 (1968): accord Braka v. Bancomer, S.A.. 589 F.Supp. 1465. 1473 (S.D.N.Y1984), affd, 762 F.2d 222 (2d Cir. 1985).

22 Significantly, the Court In Sabbatino articulated the treaty exception in negative rather than positive terms: It stated that “the Judicial Branch will not examine the validity of a (foreign act of stale] ... in the absence of a treaty or other unambiguous agreement,” id, but did not stale the converse, namely, that if a treaty exists then the act of state doctrine does not apply.

23 Compare H. Smit, N. Galston 4k S. Levitsky. International Contracts $ 6.06(1 Kb), at 165-66 (“current transactions” include international deposits) with Evans, Current and Capital Transactions: How the Fund Defines Them, 5 Fin. & Dev. 30, 34 (1968) (“current transactions” are those arising from International trading activities). See generally F. Mann, The Legal Aspect of Money 396 (4lh ed. 1982) (“extremely difficult” to determine meaning of “‘current transactions’ which is only very inadequately defined” by the Fund Agreement); J. Gold, The Cuban Insurance Cases and the Articles of the Fund 37-45 (IMF Pamphlet Series no. 8, 1966) (discussing confusion surrounding terms “capital” and “current” transactions).

24 The Callejos contend thai the Fund Agreement need not be unambiguous lo fall within the scope of the treaty exception, since the term “unambiguous” in the phrase, “treaties and other unambiguous agreements,” modifies only “other agreements” and not “treaties.” This reading of the treaty exception, however, not only strains the syntax of the sentence; it is also directly contrary to the policy considerations underlying the act of state doctrine, namely, to forestall the courts from adjudicating cases when there are no agreed upon controlling legal principles.

25 Although the Callcjos did not question the sufficiency of the Fund's May 3 letter before the district court, they argue on appeal that the letter is inadequate evidence of the Fund's position since, under Art. VIII. § 2(a) and Art. XXIX, only the Executive Board of the Fund can approve exchange regulations and offer interpretations of the Fund Agreement. In response, Bancomer attached as appendices to its brief copies of two letters, one from the Secretary of the IMF stating that the May 3 letter had been authorized by the Executive Board of the IMF, and the other from the Director of the Legal Department of the IMF stating that the Executive Board approved the Mexican exchange control regulations on December 23, 1982. Since these letters were not introduced into evidence in the court below, they cannot be considered by us on appeal. United States v. One 1978 Piper Navajo PA-il Aircraft, 748 F.2d 316. 319 (5th Cir.1984); Titus v. Mercedes Bent of North America, 695 F.2d 746, 756 n. 3 (3rd Cir.1982); Fed.R.App.P. 10(a). By the same token, however, we cannot consider arguments raised for the first time on appeal, especially where, as here, the failure to raise them before the district court has prejudiced the other side's ability to respond. See supra note 20.

Although the May 3 letter is not dispositive of the Fund's position, we believe that it is prima facie evidence. Because the Callejos failed to offer any evidence to rebut or otherwise undermine the letter, we believe that they failed to raise a genuine issue of fact regarding the Fund's approval of the Mexican regulations. This result is buttressed by the IMFs general interpretive view that currency regulations should be presumed to be in conformity with the Fund Agreement unless the Fund indicates otherwise. See I J. Ilorscfield, The International Monetary Fund, I94S-I965, at 210 (1969) (discussing the Legal Department's opinion letter of Oct. 29, 1948). Under this view, it is the plaintiffs burden to demonstrate that the IMF disapproved the currency regulations in question, rather than the defendant's burden to prove the converse. Here, the Callejos introduced no evidence that the Fund has disapproved the Mexican regulations.

26 According to some commentators, since Art. XXIX of the Fund Agreement makes interpretations by the Fund binding on signatory nations, they are subsidiarily binding on the courts of signatory nations, including those of the United States. See 1. Gold, Interpretation by the Fund 31-42 (IMF Pamphlet Series No. II, 1968) (discussing predecessor of Art. XXIX). We express no view on this question here, and employ the Fund's interpretation merely as persuasive rather than as binding authority. See Braka v. Bancomer, S.A., 589 F.Supp. 1465. 1473 (S.D.N.Y. 1984) (citing letter from Director of Legal Department of IMF as authority that Mexican exchange control regulations do not violate Fund Agreement), affd. 762 F.2d 222 (2d Cir.1985); Restatement (Revised), supra note 13, at § 325 reporters' note 4.

27 Bancomer contends that if the Mexican exchange control regulations were promulgated in conformity with the Fund Agreement, we must dismiss this case under Art. VIII. § 2(b) of that Agreement, which forbids courts from enforcing “exchange contracts” involving the currency of a Fund member that violate the member's currency regulations. See 22 U.S.C. § 286h (1982) (incorporating Art. VIII. § 2(b) into U.S. law). In essence, § 2(b) is an internationally imposed act of state doctrine. Since we already dismiss the case under our own domestic act of stale doctrine, we need not consider this additional defense. Cf. Libra Bank Ltd. v. Banco Nacional de Costa Rica, 570 F.Supp. 870, 896 n. I (S.D.N.Y. 1983) (discussing relation of Art. VIII. § 2(b) and act of stale doctrine).

28 The Fund itself, in recognition of the fact that it is not always possible to obtain prior approval when exchange controls are imposed to preserve national security, has adopted more flexible procedures under which members must merely give notice to the Fund of the imposition of exchange controls. Unless the Fund specifically disapproves the controls, members are entitled to assume that the Fund approves the controls. See 3 International Monetary Fund I94S-I96S: Documents 257 (J. Horsefield ed. 1969).

29 Even when an act of a foreign state affects property outside of its territory, however, we may still give effect to the act if doing so is consistent with United States public policy. Maltina. 462 F.2d at 1026-27; accord Banco National de Cuba v. Chemical Bank New York Trust Co., 658 F.2d 903, 908-09 (2d Cir. 1981); United Bank Ltd v. Cosmic Int'l. Inc., 542 F.2d 868. 872-73 A n. 7 (2d Cir. 1976); Republic of Iraq v. First Natl City Bank, 353 F.2d 47, 51 (2d Cir.1965). cert, denied 382 U.S. 1027, 86 S.Ct. 648. 15 I.Fd.2d 540 (1966); see also Libra Bank Lid. v. Banco Nacional de Casta Rica, 570 F.Supp. 870. 877, 882 (S.D.N.Y.I983); Restatement (Second), supra note 12. at § 43(2) (“A court in the United Stales will give effect to an act of a foreign state (with respect to a thing located, or an interest localized, outside of its territory) ... only if to do so would be consistent with the policy and law of the United States.”); cf. United States v. Belmont, 301 U.S. 324, 332, 57 S.Ct. 758, 761, 81 L.Ed. 1134 (1937) (applying Russian governmental decree to bank deposits in New York or. ground that this furthered United States policy). Although the fact that the property is located outside of the foreign state reduces the potential for offense, the considerations underlying the act of stale doctrine may still be present. See Maltina, 462 F.2d at 1029 (differences are only of degree). A foreign stale's interest in the enforcement of its laws does not always end at its borders. In the present case, however, since we find thai the situs of the certificates was Mexico and not the United states, we do not reach the second prong of the territorial limitation test, namely, whether recognizing Ihe Mexican decrees would be consistent with Ihe policy and law of Ihe United Stales. Cf. Allied Bank Intl v. Banco Credito Agricola. 757 F2d 516. 519-20 (2d Cir.1985) (on rehearing) (holding that Cosla Rican regulations suspending the repayment of external debt were contrary lo American public policy).

30 It is unclear what result would have been reached in Tabacalera if the American debtor had had assets in Cuba, since then Cuba would have been in a position to perform a fail accompli by seizing these assets. Arguably, the situs of the debt might still have been the United States on the ground that the assets in Cuba were not the same assets as those owed by the American company. However, this would depend on an independent test Tor locating the situs of the obligation; it would be circular to argue that Cuba could not collect the debt because the debt was not located in Cuba, if the location of the debt was itself defined in terms of where it could be collected.

31 These factors have been used on a number of occasions to determine the situs of debts owed by foreign banks. In Garcia, for example, the court located in the United States a certificate of deposit issued by Chase Manhattan's Cuban branch, on the ground that the certificate was guaranteed by Chase's New York office and could be repaid by presentation at any Chase branch. 735 F.2d at 650. Similarly, in Libra Bank, the court determined that the situs of a loan to a Costa Rican bank was the United States, since the loan agreement provided that New York law would govern, the Costa Rican bank consented to the jurisdiction of American courts, the place of payment was Chase Manhattan's New York branch, and the Costa Rican bank had substantial assets in the United States. 570 F.Supp. at 881-82. As the court noted. “The Costa Rican decrees attempted to alter the legal relations between the parties with respect to the debt by extinguishing the legal right to repayment, the only property in question, whose situs was in New York.” Id. at 882; see also Allied Bank, 757 F.2d at 521 (situs of promissory notes issued by Costa Rican banks to syndicate of 39 creditor banks was New York, where notes payable, negotiations held, and syndicate agent located); Weston Banking Corp. v. Turkiye Garanti Bankasi, 57 N.Y.2d 315. 456 N.Y.S.2d 684, 442 N.E.2d 1195 (1982) (situs of promissory note issued by Turkish bank to Panamanian bank was United States, since note designated New York as proper jurisdiction for the resolution of disputes and as place of payment); Restatement (Revised), supra note 13, at § 469 reporters' note 4; cf. Dunn v. Bank of Nova Scotia. 374 F.2d 876. 877-78 (5lh Cir.1967) (situs of deposit at place of deposit, unless alternative place of payment designated).

32 The Callejos claim that Ihe deposits were nevertheless sitused in Texas on Ihe ground that this was Ihe intent of the parties. This evidence, however, is inadmissible, given that the certificates of deposit were integrated contracts and are subject to the parol evidence rule. Where certificates of deposit clearly specify a place of payment, parol evidence thai a different place of payment was intended should be disregarded in the absence of fraud, duress, or mutual mistake. See 32A CJS. Evidtnct § 895 at 254 (1964).

33 In their revised complaint, the Callejos alleged violations of § 12(1) of the Securities Act of 1933. 15 U.S.C. f 77/(1)0982). and § 33A.(I) of the Texas Securities Act, Tex.Rev.Civ.Stal. Ann. art. 58I-33A.O), as well as breach of contract. We agree with the Callejos that these securities claims are not barred by the act of stale doctrine, since they are based on Bancomer's initial failure to register the certificates of deposit, not on Bancomer's later breach of the certificates by complying with Mexico's exchange control regulations. Adjudicating these claims would not involve reviewing the validity of the exchange control regulations. Cf. Arango v. Guzman Travel Advisors Corp., 621 F.2d 1371, 1380-81 (5th Cir.lSSO) (holding that act of state doctrine only barred plaintiffs' battery and false Imprisonment claims, not plaintiffs' contract and negligence claims since these did not necessitate an evaluation of the legitimacy of the Dominican Republic's acts of state). We dismiss these claims, however, on the ground that the certificates of deposit sold by Bancomer were not “securities” within the meaning of the federal and Texas securities laws. We agree with the recent opinion of the Ninth Circuit In Wolf v. Banco Nadonal de Mexico, 739 F.2d 1458 (9th Cir.1984), cert, denied,—US.—105 S.Ct. 784, 83 LEd.2d 778 (1985), that purchasers of certificates of deposit issued by Mexican banks are adequately protected by Mexican banking law and consequently do not require the protections afforded by federal securities laws. Id. at 1463. This conclusion also applies to Ihe Callejos' claims under the Texas Securities Act, since the decisions of federal courts construing the meaning of “securities” under the federal act arc considered by Texas courts to be a “reliable guide” to the definition of “securities” under the Texas Act. First Municipal teasing Corp. v. Blankenship, Polls, Aikman, Hagin & Stewart, 648 S.W.2d 410. 414 (Tex.App—Fort Worth 1983, writ refd n.r.e.).