No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

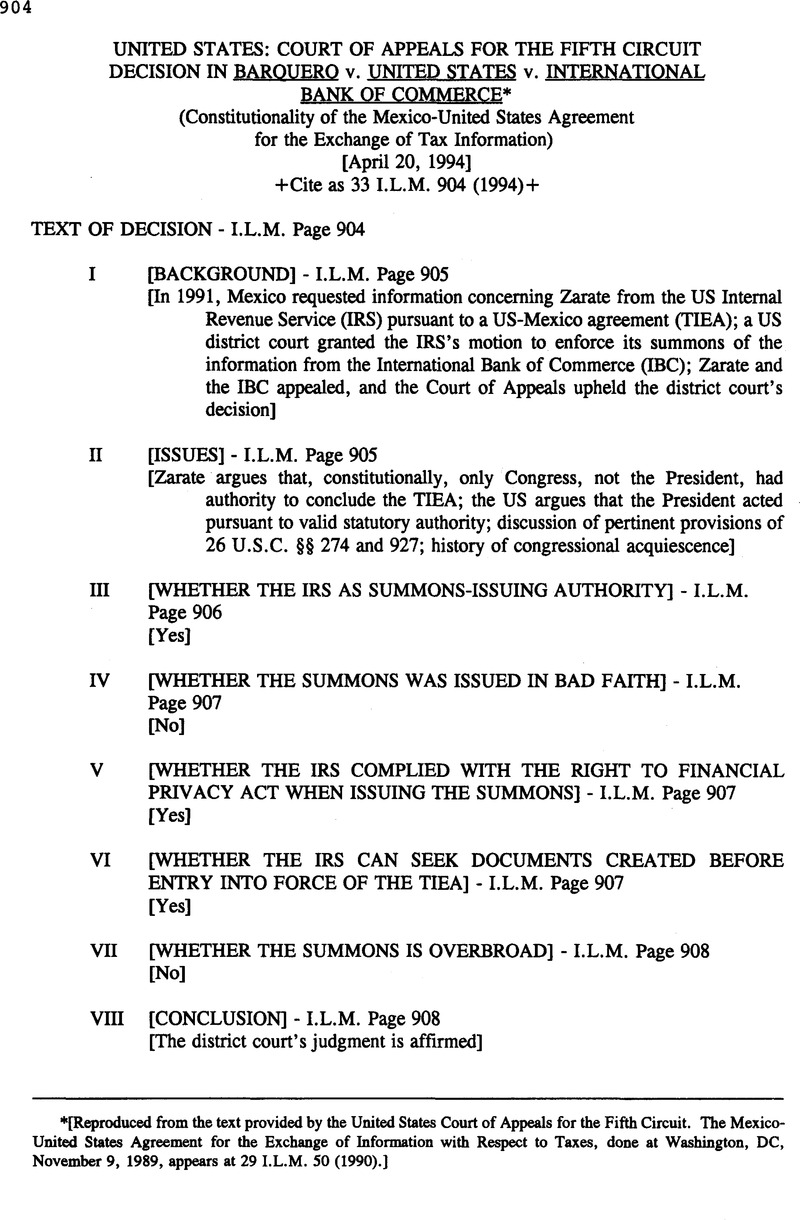

[Reproduced from the text provided by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. The Mexico- United States Agreement for the Exchange of Information with Respect to Taxes, done at Washington, DC, November 9, 1989, appears at 29 I.L.M. 50 (1990).]

1 As its name suggests, a TIEA is an agree ment providing for the exchange between two countries of tax or taxrelated information that may otherwise be subject to nondisclo sure laws of each country. 26 U.S.C § 274(h)(6XCXi). A TIEA allows both coun tries to obtain from each other information that “may be necessary or appropriate to car ry out and enforce the[ir] tax laws.“ Id.

2 Pursuant to a delegation from the Secretary of the Treasury, the IRS is the “competent authority” of the United States. The TIEA charges the competent authorities of each country with carrying out all exchanges of information between the two countries.

3 The Caribbean Basin Economic Recovery Act is also known as the Caribbean Basin Initiative (“CBI“). Beneficiary countries that enter into TIEAs with the United States gain several benefits, the most notable being that they become eligible for project financing un der § 936 of the Code.

4 The government did not argue in its brief that the President, pursuant to his own consti tutional authority, could lawfully enter into the TIEA.

5 Clause (ii) of § 274(hX6)(C) provides: An exchange of information agreement need not provide for the exchange of qualified confidential information which is sought only for civil tax purposes if— (I) the Secretary of the Treasury, after making all reasonable efforts to negotiate an agreement which includes the exchange of such information, determines that such an agreement cannot be negotiated but that the agreement which was negotiated will significantly assist in the administration and enforcement of the tax laws of the United States, and(II) the President determines that the agreement as negotiated is in the national security interest of the United States. 26 U.S.C. § 274(h)(6XC)(ii).

6 See 26 U.S.C. § 927(eX3) (1982).

7 The report was promulgated in 1988 when Congress corrected technical errors in the 1986 Tax Reform Act.

8 Zarate argues that the 1986 amendment to § 927(e)(3) “merely provides that if the Secre tary did enter into [TIEAs with nonbeneficia ry countries], the foreign countries who are party to those agreements could qualify as a host country [sic] for FSCs.“ In Zarate's opinion, before the Secretary actually could enter into a TIEA with a nonbeneficiary country, Congress would need to pass a stat ute specifically authorizing the proposed TIEA. We disagree. Section 927(eX3)'s crossreference to and incorporation of § 274(hX6XC) and redefinition of the term “beneficiary country“ demonstrates Con gress's intent to authorize the Secretary to negotiate and conclude a TIEA with “any foreign country.“ 26 U.S.C. § 927(eX3XA).

9 See State Dept. Rel. No. 9085 (noting that the TIEA at issue “was concluded pursuant to section 274(h)(6)(C) of the Code, which is incorporated by reference and implication in section 936(d) of the Code, as amended by .. the Tax Reform Act of 1986“).

10 This, of course, does not mean that every crossreference in the Code incorporates and amends the referenced provision.

11 See Restatement (Third) of Foreign Rela tions Law of the United States § 303 cmt. e (stating that “Congress may enact legislation that requires, or fairly implies, the need for an agreement”) (emphasis added).

12 See also 26 U.S.C. § 610300 (“A return or return information may be disclosed to a competent authority of a foreign government which has … [a] convention or bilateral agreement relating to the exchange of tax information!] with the United States“).

13 In addition to the U.S.—Mexico agree ment, the President has signed TIEAs with Columbia and Peru, both nonbeneficiary countries, without any indication of congres sional disapproval. See Financial Times, Oct. 1993. available in Lexis, Nexis Library (IRS announces the signing of a TIEA with Colum bia); U.S. Signs AntiDrug Pacts with Bolivia and Peru, Reuters, February 1990, available in LEXIS, Nexis Library. At one time, the Presi dent also was actively negotiating with Boliv ia regarding the possibility of entering into a TIEA. See Treasury Department Announce ment of Status of Negotiations of Income Ta Treaties and Tax Information Exchange Agret ments, Daily Report for Executives, April !1993, available in LEXIS, Nexis Library.

14 In September 1992, the United States an Mexico signed a comprehensive income ta convention. Article 27 of the conventio states that “[t]he competent authorities [c both countries] shall exchange information a provided in the Agreement Between the Unil ed States of America and the United Mexica: States for the Exchange of Information wit Respect to Taxes signed on November S 1989.” Convention Between the Governmer of the United States of America and the Gov eminent of the United Mexican States for th Avoidance of Double Taxation and the Prt vention of Fiscal Evasion with Respect Taxes on Income, September 18, 1992, U.S.Mex., art. 27, S. Treaty Doc. No. 7, 103 Cong., 1st Sess. 52 (1993). The Presiden transmitted the convention to the Senate ii May 1993, and the Senate advised and con sented to the ratification of the convention oi November 20. 1993. See 139 Cong.Rec S16857O1 (daily ed. Nov. 20, 1993).3.

15 Zarate, without citing any authority, complains that the IRS did not issue the summons in conformity with applicable statutes because the TIEA was not published in “a compilation entitled ‘United States Treaties and Other International Agreements,'” I U.S.C. § 112a, and was not transmitted to Congress within sixty days after the TIEA “entered into force,” I U.S.C. § 112b. However, Zarate did not contend before the district court that these facts demonstrated that the IRS issued the summons in bad faith. Accordingly, we need not address these issues. See Alford v. Dean Witter Reynolds. Inc., 975 F.2d 1161, 1163 (5th Cir.1992) (noting that we need not consider issues raised on appeal if they were not raised before the district court). While Zarate did raise these issues below regarding the validity of the TIEA. he does not argue on appeal that the TIEA is unconstitutional or invalid for these reasons. See United States v. ValdioseraGodinez, 932 F.2d 1093, 1099 (5th Cir. 1991) (“Any issues not raised or argued in the appellant's brief are considered waived and will not be entertained on appeal.“), cert. denied, — U.S., 113 S.Ct. 2369, 124 L.Ed.2d 275 (1993).

16 We note that neither Zarate nor IBC argued that the summons was overly burdensome. See Wyatt. 637 F.2d at 302 n. 16 (noting that the concept of burdensome is distinct from the concept of overbreadth).

17 Zarate further argues that the district court erred both by examining in camera the Mexican competent authority's request that the IRS obtain the information at issue and a letter from Mexican authorities demonstrating that their investigation Into Zarate's tax liability was not barred by any Mexican statute of limitations and by denying Zarate the opportunity to conduct discovery. However, “the method and scope of discovery allowed In summons enforcement proceedings are committed in large part to the discretion of the district court.” United States v. Johnson, 652 F.2d 475, 476 (5th Cir.1981). Here, the challenged actions do not constitute an abuse its discretion by the district court. See id.; cf. Barrett, 837 F.2d at 1349 (noting that summons enforcement “proceedings are intended to be summary In nature“).