No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

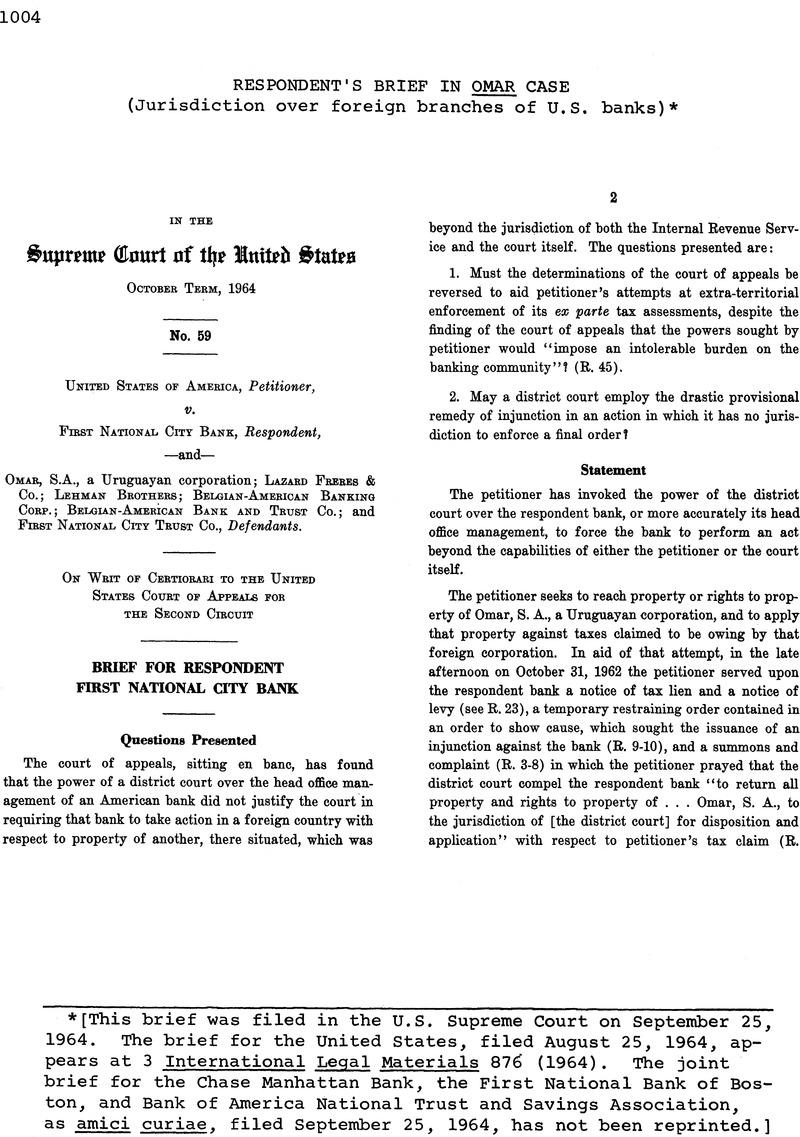

Respondent's Brief in Omar Case (Jurisdiction over foreign branches of U.S. banks)*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 May 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1964

Footnotes

[This brief was filed in the U.S. Supreme Court on September 25, 1964. The brief for the United States, filed August 25, 1964, appears at 3 International Legal Materials 876' (1964) . The joint brief for the Chase Manhattan Bank, the First National Bank of Boston, and Bank of America National Trust and Savings Association, as amici curiae, filed September 25, 1964, has not been reprinted.]

References

page 1005 note * For the purposes of argument, we will assume, as did the court appeals, that at the time of service of the papers Omar maintained account at the Montevideo branch of the respondent bank.

page 1005 note ** The decision of the court of appeals has been favorably reviewed legal periodicals. E.g., 64 Colum. L. Rev. 774 (1964); 62 Mich. Rev. 1084 (1964);

“The instant decision reaffirms and reinforces a body of law long recognized in the field of foreign branch banking. Without the separate entity doctrine, the stability of our branch banking system would be greatly altered. For reasons of precedent and practicality, this court [the Second Circuit] reached a sound decision in extending the doctrine to apply to an injunction proceeding.” 9 Vill. L. Rev. 339, 343 (1964).

page 1006 note * Petitioner's statement "We stress that this injunction was not equivalent to garnishment, seizure or attachment" (Pet. Br. pp. 11-12) is inconsistent with petitioner's subsequent arguments that "The dis trict court's exercise of jurisdiction over the debt" was proper (Pet. Br. p. 28), and that New York law could not prevent attachment or garnishment in this case (Pet. Br. pp. 29-30).

page 1008 note * It is to be noted that the petitioner's attitude toward New York law is ambivalent. Petitioner urges with some vigor that Section 302 of the New York Civil Practice Law and Rules relating to the in personam jurisdiction of New York courts is available to confer juris diction upon a federal court in an action under a federal statute to collect a federal tax. (Pet. Br. pp. 17-18). With equal enthusiasm petitioner urges upon the court that the long-established New York rule as to the existence or non-existence of property and property rights is a "local rule [which] should not control in a federal tax-col lection proceeding". (Pet. Br. pp. 29-30)

page 1011 note * See e.g., McCloskey v. Chase Manhattan Bank, 11 N. Y. 2d 936, 183 N. E. 2d 227 (1962) ; Varga v. Credit-Suisse, 2 A. D. 2d 596, 157 N. Y. S. 2d 391 (App. Div., 1st Dept. 1956) ; Clinton Trust Co. v. Compania Azucarera Central Mahay, S. A., 172 Misc. 148, 14 N. V. S. 2d 743 (Sup. Ct., . Y. Co. 1939), aff'd without opinion, 258 App. Div. 780, 15 N. Y. S. 2d 721 (1st Dept. 1939) ; Gomales v. Pardo, N. Y. L. J. Nov. 30, 1950, p. 1380, col. 5 (Sup. Ct. . Y. Co., 1950) ; Newtown Jackson Co. v. Animashun, 148 N. Y. S. 2d 66 (Sup. Ct. Nassau Co., 1955) ; Cronan v. Schilling, 100 N. Y. S. 2d 474 (Sup. Ct. . Y. Co. 1950) ; Walsh v. Bustos, 46 N. Y. S. 2d 240 (City Ct., . Y. Co. 1943) ; Bluebird Undergarment Corp. v. Gomez, 139 Misc. 742,249 . Y. Supp. 319 (City Ct, . Y. Co. 1931).

These cases are entirely consistent with 12 U. S. C. 604, which requires respondent to "conduct the accounts of each foreign branch independently of the accounts of other foreign branches established by it and of its home office."

page 1012 note * This rule and this interpretation of Harris v. Balk represent the law today. The Copperfield, 7 F. 2d 499 (S. D. Ala. 1925), afd, sub nom. Aktieselskabet Dea v. Wrightson, 26 F. 2d 175 (5th Cir. 1928), cert. den. 278 U. S. 623 (1928) and Schlaefer v. Schlaefer, 112 F. 2d 177 (D. C. Cir. 1940) (dictum), cited by petitioner at pages 27 28 of its brief, neither alter nor erode the principle. In The Copper field, the court's decision was based, inter alia, upon a state statute which expressly authorized the proceeding,? in contrast to New York law which unequivocally prohibits this proceeding. In Schlaefer, the determinative reason for the court's decision was that all parties had appeared and submitted to the jurisdiction of the court.

page 1014 note * An injunction anticipates, but cannot exceed, the ultimate sanction which the court is authorized to impose. The extraordinary power of a district court to issue preliminary injunctions should only be exercised upon a showing that the prospect of the applicant's ultimate success is so great that the ultimate sanction of the court may be accelerated.

Hall Signal Co. v. General Ry. Signal Co., 153 Fed. 907 (2d Cir. 1907) ;

Yonkers Raceway v. Standardbred Owner's Ass'n., 153 F. Supp. 552 (S. D. N. Y. 1957) ;

Nadya, Inc. v. Majestic Metal Specialties, 127 F. Supp. 467 (S. D. N. Y. 1954).

In none of the approximately 50 cases we have found which cite Hall, culminating in H. E. Fletcher Co. v. Rock of Ages Corp., 326 F. 2d 13 (2d Cir. 1963), is there dissent from its holding that:

“It is a cardinal principle of equity jurisprudence that a pre liminary injunction shall not issue in a doubtful case. Unless the court be convinced with reasonable certainty that the com plainant must succeed at final hearing the writ should be denied.” 153 Fed. at 908.

page 1015 note * The court of appeals found that Omar's absence was significant, but only in terms of distinguishing one case, United States v. Ross, 302 F. 2d 831 (2d Cir. 1962? (Pet. Br. p. 11). Omar's absence was not, as petitioner suggests, the sine qua non of the decision.

page 1016 note * McGee v. International Lije Insurance Co., 355 U. S. 220 (1957) ; International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U. S. 310 (1945).

page 1016 note * "The future of American foreign banking is more important than collection of a few million dollars of a few million dollars of somebody's delinquent taxes-if indeed they ever can be collected."

page 1019 note * Editorial, The Journal of Commerce and Commercial (New York,. Y., June 11, 1964).

page 1020 note * The respondent alone is served with approximately 2,000 Federal tax levies each year.