Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

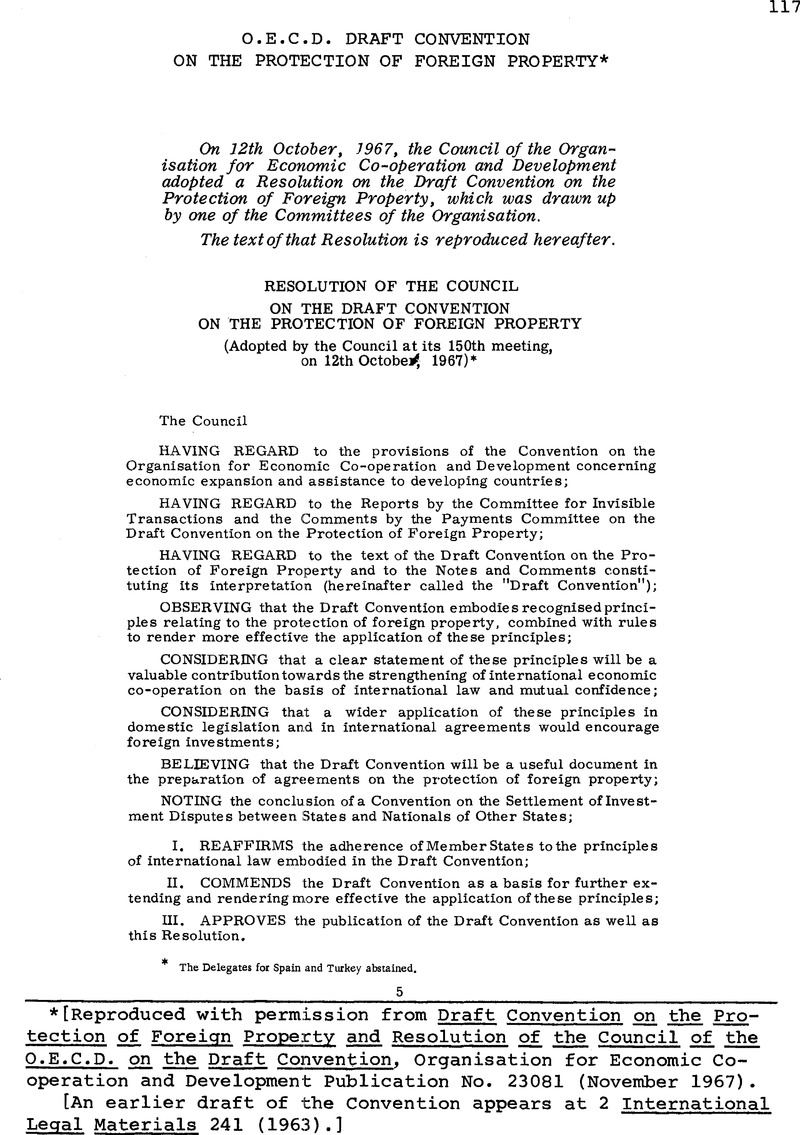

[Reproduced with permission from Draft Convention on the Protection of Foreign Property and Resolution of the Council of the O.E.C.D. on the Draft Convention, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development Publication No. 23081 (November 1967).

[An earlier draft of the Convention appears at 2 International Legal Materials 241 (1963).]

* The Panevezys-Saldutiskis Railway Case, quoted in Edvard Hambro, The Case Law of the International Court, Vol. I, (hereinafter referred to as “Hambro I”) No. 348, p. 289.

** Mavrommatis Case, quoted in Hambro I, No.347, p. 289.

*** See, for instance. United States-German Treaty, Article V (1); United States-Nicaraguan Treaty, Article VI(1); and also United Kingdom-Iranian Treaty, Article 8(1).

* Recent bilateral treaties frequently provide for the exclusion of unreasonable and discriminatory measures. See United States-Netherlands Treaty, Article VI (3); also United States-Japanese Treaty, Article V(l); United Kingdom-Iranian Treaty, Article 8 (2), etc.

* Advisory Opinion on Conditions of Admission to the United Nations, ICJ Report 1947–48, p. 57 to p. 80 ; see also p. 83.

** Polish Upper Silesia Case and Free Zones of Upper Savoy Case, quoted in Hambro I, Nos. 100–101, p. 73.

*** See Hambro I, Nos 246 and 315, at pp. 201 and 261.

* See The Right Honourable Lord Shawcross, Q.C. : The Problems of Foreign Investment in International Law, in Hague Recueil, 1961.

** (1929) Series A, Nos. 20/21. In his lecture (ibidem) Lord Shawcross quotes other authorities in support of this principle.

* Sir Hersch Lauterpacht, Règles gènèrales du Droit de la Paix. In Hague Recueil, 1937 (iv), pp. 95 et seq., and p. 346.

** See e.g. United States-German Treaty, Article V (4); United States-Italian Treaty, Article V(2). Not all United States Bilateral Treaties refer, however, to “due process of law” as a requirement : see e.g. United States-Greek Treaty, Article 7(3).

* See Wortley, B.A., Expropriation in Public International Law, Cambridge, 1959, p. 139 Google Scholar.

** Arbitral Award in the United States-Cuban claim, Fletcher Smith, W., (1929) Reports of International Arbitral Awards, Vol. II, pp. 915–918 Google Scholar.

*** See Wilson, R.R., United States Commercial Treaties and International Law, New Orleans, La., 1960, p. 115 Google Scholar.

* See footnote** p. 24.

** See, for instance, German-Pakistan Treaty, Art. III (2) and German-Togoland Treaty, Art. 3(2).

*** United States-Japanese Treaty, Article VI(3); United States-German Treaty, Article V(4); United States-Netherlands Treaty, Article VI (4).

* United States-Ethiopian Treaty, Article VIII (2).

** See footnote ***, page 20.

* Chorzow Factory Case, (1928) Series A, No. 17, p. 47.

* Charles Rousseau, Principes Généraux du Droit International Public, Tome I. p. 573.

* “... Necessity may excuse the non-observation of international obligations.,, the plea of necessity . . . by definition implies the impossibility of proceeding by any other method than the one contrary to law”, declared Judge Anzilotti in the Oscar Chinn Case (P.C.I.I. Series A/B No. 63, P. 114).

** See, for example, United States-Italian Treaty, Article XXIV; United States-Greece Treaty, Article XXIII; United States-Federal Germany Treaty, Article XXIV; United States-Nicaraguan Treaty, Article XXI; and also Norwegian-Japanese Treaty, Article XVI.

* See The Permanent Court of International Justice in the Tunis and Morocco Nationality Decrees Case : “In the present state of international law, questions of nationality are . . . in principle . . . solely within the jurisdiction of a State” (P.C. I.J., Series B, No. 4, p. 24); also Sir Hersch Lauterpacht : “It is not for international law but for municipal law to determine who is, and who is not, to be considered a subject* (Oppenheim-Lauterpacht, International Law, Vol. I, 8th Ed., p. 643).

** See Strupp -Schlochauer, Wörterbuch des VSlkerrechts, Vol. I, p. 381; see also The Hague Convention of 1930 on Certain Questions relating to the Conflict of Nationality Laws, Article 14.

*** Sir Hersch Lauterpacht, The Development of International Law by the International Court, London, 1958, p. 183; for exceptions to this rule, see ibidem, p. 382 and Martin, andrew, Private Property Rights, and Interests in the Paris Peace Treaties, in (1947) B.Y.I.L., Vol. 24, p. 286 Google Scholar.

* Nottebohm Case (2nd phase), quoted in Hambto II. No. 138, pp. 193–195; see also The Hague Convention of 1930, Article 5.

** Parry, Clive, Nationality and Citizenship Laws of the Commonwealth, London, 1957, p. 26 Google Scholar.

*** See Bindschedler, R.L., La protection de la propriét’e privde en droit international public, in Hague Recueil, 1956 (ii), p. 179 Google Scholar, as to the tests applied in the post-war compensation treaties, see Foighel, I., Nationalisation, London, 1957, pp. 110–111 Google Scholar.