Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

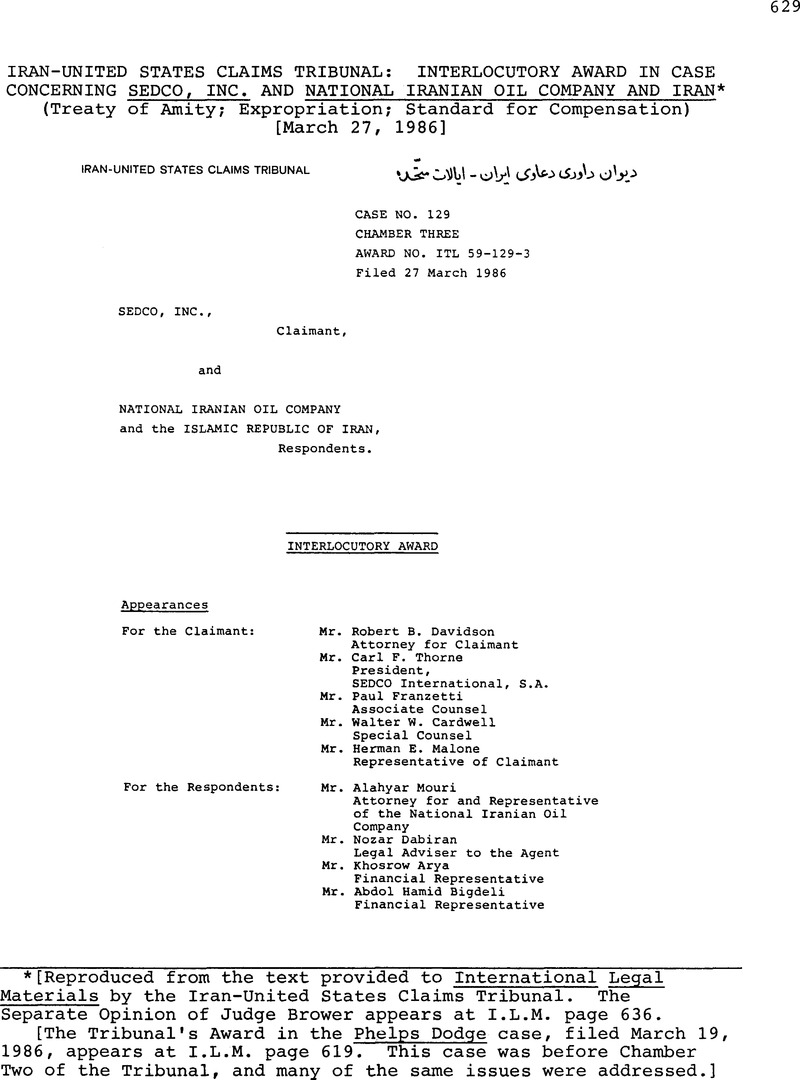

* [Reproduced from the text provided to International Legal Materials by the Iran-United States Claims Tribunal. The Separate Opinion of Judge Brower appears at I.L.M. page 636.[The Tribunal's Award in the Phelps Dodge case, filed March 19, 1986, appears at I.L.M. page 619. This case was before Chamber Two of the Tribunal, and many of the same issues were addressed.]

1 Treaty of Amity, Economic Relations, and Consular Rights between the United States of America and Iran , signed 15 August 1955, entered into force 16 June 1957, 284 U.N.T.S. 93, T.I.A.S. No. 3853, 8 U.S.T. 899.

2 In the event, however. Claimant has not sought the value of Sediran as a going concern. Instead it seeks only its 50 per cent share of what it calls “the Company's liquidation value as at 22 November 1979”, assuming, “in effect, the winding up of Sediran's affairs and the disposition of its assets - most of which were movable - on the open market.” The assets of Sediran consisted principally of ten drilling rigs and associated transportation equipment, spare parts and camps. Sediran's assets also included, however, warehouse facilities, land and other fixed assets. Furthermore, the assets of Sediran listed by Sedco in a reconstructed balance sheet as of 22 November 1979 encompass as well a substantial amount of receivables based on allegedly unpaid invoices submitted under two drilling contracts. With respect to the drilling rigs. Claimant additionally seeks damages for the loss of use of the rigs for a nine month period, the time allegedly needed to replace a rig. Claimant labels this part of its claim as damages for “lost profits.” This loss appears, however, to be a direct loss resulting from the unavailability of the rigs to Claimant for use elsewhere and as such is damnum emergens. According to Claimant, the liquidation value thus asserted constitutes “the absolute minimum measure of damages”, whereas “[a]ny considered analysis based upon the valuation of Sediran as an ongoing business enterprise as at 22 November 1979 … would yield a higher equity value.” Sedco also claims interest computed from the date of the taking. Claimant originally valued the property as of 30 June 1979, the last day of the last financial year for which Sediran's accounting records are fully available. After the Tribunal found that the expropriation took place on 22 November 1979, Claimant submitted on 13 December 1985 a new balance sheet adjusted to reflect the situation on the date of the taking. No adjustments have been made, however, to the alleged value of the oil rigs as of 30 June 1979. In addition to adjustments reflecting the finding concerning the date of expropriation. Claimant purported to make certain modifications (an increase of $4,602,072) to its earlier calculation of damages. These other changes were rejected as untimely in the Tribunal's Order of 6 January 1986.

3 But see note 2 supra.

4 The only objection raised in this Case not addressed by the award in Phelps Dodge, namely the application of the Treaty of Amity to non-U.S. nationals, is no longer relevant given the holding in the previous Interlocutory Award in this Case that the claim concerning the expropriation of Sediran is a direct shareholder claim of Sedco.

5 See note 2 supra.

6 See, e.g., Dolzer, “Expropriation and Nationalization”, in 8 Encyclopedia of Public International Law 214 (1985), who, when summarizing the current situation, has stated that “the opinions expressed by industrialized States and developing States with respect to the rules of international law are widely divergent, and the conduct of States in actual practice coincides with none of these expressed views.” Id. at 216.

7 As regards settlements between a State and a foreign company, the latter's practice in any case could not be interpreted necessarily to reflect opinio juris of the State of its nationality. P

8 See, e.g., Barcelona Traction (Belg. v. Spain), I.C.J. Rep. 1970, p. 3, at 40 (Judgement of 5 Feb. 1970).

9 See, e.g., Kuwait v. The American Independent Oil Company (“AMINOIL“), paras. 156-157 (Reuter, Sultan & Fitzmaurice arbs.. Award of 24 Mar. 1982), reprinted in 21 Int'l Legal Mat'Is 973, 1036 (1982).

10 Aminoil, supra note 9 at para. 157.

11 G.A. Res. 3201, 28 U.N. Gaor Supp. (No. 1) at 3, U.N. Doc. A/9559 (1974), reprinted in 13 Int'l Legal Mat'Is 715 (1974).

12 G.A. Res. 3281, 29 U.N. Gaor Supp. (No. 31) at 50, U.N. Doc. A/9631 (1974), reprinted in 14 Int'l Legal Mat'Is 251 (1975).

13 G.A. Res. 1803, 17 U.N. Gaor Supp. (No. 17) at 15, U.N. Doc. A/5344 (1962) , reprinted in 57 Am. J. Int'l L. 710 (1963).

14 According to Article 11 of the United Nations Charter they are only non-binding recommendations. Reprinted in I. Brownlie (ed.), Basic Documents in International Law 2 (1978). Nor are such resolutions included among the accepted sources of international law as listed in Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice. Reprinted id. 267.

15 Schwebel, “The Legal Effect of Resolutions and Codes of Conduct of The United Nations,” 7 Forum Internationale (1985)

16 For a more detailed discussion presenting arguments for both views, see, on the one hand, Separate Opinion of Judge Holtzmann in INA Corporation and Islamic Republic of Iran, Award No. 184-161-1 (15 Aug. 1985), and, on the other hand. Separate Opinion of Judge Lagergren filed in the same case.

17 Such writers, in arguing for a standard of "partial" rather than "full" compensation, also have concentrated on discounting elements of damage not claimed here, such as lost profits or value as a going concern.

18 As some of these opinions are expressed in the context of large-scale nationalization cases, they should ji fortiori weigh heavily in a case such as the one here presented.

19 Cf. Clagett, "The Expropriation Issue Before the Iran-United States Claims Tribunal: Is 'Just Compensation' Required by International Law or Not?", L. & Pol'y Int' 1 Bus. 813, 858 (1984); Gann, "Compensation Standard for Expropriation," 23 Col. J. Transnat'l L. 615, 633 (1985).

20 Liamco, p. 32, 21 Int'l Legal Mat'Is at 67. This statement of principle was made in connection with a general discussion concerning international law on the subject, and was reached without regard to the fact that in that particular case the claimant's right to full compensation for its assets was further strengthened by a contractual provision according to which the concessionaire had the right to remove his physical assets after termination of the concession. Liamco, p. 155, 21 Int'l Legal Mat'Is at 79.

21 In practice this Tribunal has not applied "partial" or less than "full" compensation in any case. This was done neither in INA Corporation and Islamic Republic of Iran, Award No. 184-161-1 (13 Aug. 1985) , nor in American International Group and Islamic Republic of Iran, Award No. 93-2-3 (19 Dec. 1983), reprinted in 4 Iran-U.S.C.T.R. 96, both of which concerned nationalization of insurance companies. In Award No. 93-2-3 the Tribunal valued the company as a going concern, holding that "even in a case of lawful nationalization the former owner of the property is normally entitled to compensation for the value of the property taken." Id. at 14-15, 4 Iran-U.S.C.T.R. at 105.

22 Claimant also has claimed interest at the rate of 12 per cent from the date of the taking. In previous where a compensable taking of property has been found the Tribunal always has awarded interest from such date. In accordance with this practice and the relevant principles of international law Claimant is entitled to interest from the date of the taking, 22 November 1979. The rate of interest will be decided in the subsequent award on the quantum of damages.

1 This Award was issued by the same Chamber (Three) on the basis of a majority likewise including Chairman Mangard.

2 The applicability of the Treaty of Amity was not considered fully in INA Corporation and Islamic Republic of Iran, Award No. 184-161-1 at 9 (13 Aug. 1985), where Respondent did not contest the "continued validity and effect of the Treaty" and the Tribunal concluded that it "must therefore assume that for the purpose of the present case the Treaty remains binding as it is drafted."

3 Article XXIII of the Treaty of Amity provides:

1 ......

2 The present Treaty shall enter into force one month after the day of exchange of ratifications. It shall remain in force for ten years and shall continue in force thereafter until terminated as provided herein.

3 Each High Contracting Party may, by giving one year's written notice to the other High Contracting Party, terminate the present Treaty at the end of the initial ten-year period or at any time thereafter.

4 See Concurring Opinion of Judge Mosk in American International Group and Islamic Republic of Iran, Award No. 93-2-3 (19 Dec. 1983) , reprinted in 4 Iran-U.S. C.T.R. 96 at 112-116

5 Although not pleaded by Respondents, I note that the Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA) reported in “Ann. of Iran's Abrogation of U.S., Soviet Friendship Agreements,” 4 Daily News 18-19 (No. 259, 11 Nov. 1984) that “On November 10, 1979 IRAN's ‘Revolution Council’ Decided To Abrogate Iran's Agreements With Both The Superpowers …Following The Seizure Of The U.S. Den Of Spies In Tehran (On Nov. 4, 1979) And Rupture Of Diplomatic Relations Between Tehran And washington the friendship agreement of 1955 sounded as Something Virtually Unwanted And unjustified. the agreement was abrogated and rightly so because the united states had frozen iran's assets in american banks. the agreement has since been null and void. ” This single unilateral indication, accepted arguendo, does not by itself accomplish termination of the Treaty under either its own provisions or the Vienna Convention.

6 Even if the Tribunal were, arguendo, to find the Treaty of Amity has been terminated since the signing of the Algiers Accords, such a termination would not affect rights which vested under the Treaty in the past. Article 70(1) of the Vienna Conevnetion, supra, provides: 1. Unless the treaty otherwise provides or the parties otherwise agree, the termination of a treaty under its provisions or in accordance with the present convention: Cl a. ... b. does not affect any right, obligation or legal situation of the parties created through the execution of the treaty prior to its termination.

7 The Tribunal therefore need not decide at present the applicability of the Treaty of Amity to the “interests” of U.S. nationals in property of non-U.S. nationals who may possess a direct claim.

8 See Art. 31, Vienna Convention, supra. The States Parties have declared in the past that the Vienna Convention, although not directly applicable by its terms, provides the governing law as to interpretation of the Algiers Accords.See,e.g., Transcript of 8 Mar. 1982 Hearing in Case Al at 88 (filed 11 Mar. 1982). I see no justification for distinguishing the task of interpreting the Treaty of Amity.

9 The Tribunal in INA Corporation at 10 further held that claimant there was entitled to interest on its judgment from the date of nationalization to the date of payment.

10 Letter from Mr. Harriman to Dr. Mossadegh, 15 September 1951, reprinted in British Royal Institute of International Affairs, Documents on International Affairs 510 (1951), quoted in G. White, Nationalisation of Foreign Property 184 (1961). It further seems clear that at the start of negotiations for the Treaty of Amity, the Iranian Foreign Ministry requested from the United States copies of similar treaties concluded by the United States. Message from U.S. Embassy, Tehran, to Secretary of State, U.S. Department of (Footnote Continued) State (16 July 1954). Likewise, during the negotiations the Iranian delegation made comparisons between drafts under consideration and other Treaties of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation concluded by the United States. See, e.g. , Message from U.S. Embassy, Tehran, to Department of State (16 October 1954). Mr. William M. Rountree, Deputy Chief and later Charge d'Affaires ad Interim of the United States Embassy in Iran (1953-55), and Mr. William H. Bray, Jr., Economic Counsellor at the United States Embassy in Iran (1954-56), apparently negotiated the Treaty of Amity on behalf of the United States. Sworn affidavits of theirs presented to this Tribunal state that “[b]ased on the Iranian's familiarity with these other [bilateral Friendship, Commerce and Navigation] treaties and discussions during the negotiations, I have no doubt that the Iranians were aware of the United States’ view of the requirements of international law and knew that the bilateral Treaties of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation entered into by the United States reflected this view.” These affidavits and diplomatic messages were filed in Case No. 56 before this Tribunal, in which both of the present Respondents also are Respondents and in which oral and written proceedings have been concluded. Under these circumstances, I believe it appropriate to refer to these here, while noting that my conclusions are arrived at independently of them.

11 “[A] ‘lump- sum’ … settlement involves an agreement arrived at by diplomatic negotiation between governments, to settle outstanding international claims by the payment of a given sum without resorting to international adjudication.” Re, “Domestic Adjudication and Lump Sum Settlement as an Enforcement Technique,” 58 Am. Soc'y Int'l L. Proceedings 39, 40 (1964). A particularly dramatic example of why such settlements are suspect as guides to the substance of customary international law is provided by United States settlements with Eastern European States following World War II. Most such settlements provided compensation at a rate of less than 40 cents on the dollar. See 1974 Digest of United States Practice in International Law 424. A proposed settlement of claims against Czechoslovakia at a rate of approximately 42 cents per dollar was rejected (see Section 408 of the Trade Act of 1974, Pub. L. 93-618), however, and the settlement eventually reached provided payment at 100 cents on the dollar. See Czechoslovakian Claims Settlement Act of 1981 Pub. L. 97-127 (not codified, reprinted in 22 U.S.C.A. §1642 note). Agreement Between the United States and Czechoslovakia on the Settlement of Certain Outstanding Claims and Financial Issues (not printed), entered into force 2 February 1982.

12 Respondents cite to Schachter, “Compensation for Expropriation,“ 78 Am. J. Int'l L. 121 (1984) and authorities cited therein.

13 compensation equalled the value of property at the date of taking plus interest); De Sabla (U.S. vs. Panama), VI Rep. Int'l Arb. Awards 358, 356-67 (Award of 29 June 1933) (“It is axiomatic that acts of a government in depriving an alien of his property without compensation impose international responsibility” and consequently “the proper measure of damages” is “to award to the claimant the full value … of her property“). See also Herz, “Expropriation of Foreign Property,” 35 Am. J. Int'1 L. 243, 265-55 (1941) (“only full and immediate compensation in cash fulfills the conditions of international law“) and Wetter & Schwebel, “Some Little-Known Cases on Concessions,” 40 Brit. Y. B. Int'l L. 183 (1964). I agree with recent commentators that although these cases did not per se adopt the exact phrase “prompt, adequate and effective” they did substantively award such full compensation. Robinson, “Expropriation in the Restatement (Revised),” 78 Am. J. Int'1 L. 176 (1984); Gann, “Compensation Standard for Expropriation,” 23 Col. J. Transnat'1 L. 615, 616 (1985); Mendelson, “Compensation for Expropriation: The Case Law,” 79 Am. J. Int’ 1 L. 414, 415 (1985). I also agree that these “cases stand on their own feet” and do not dictate expressly an “absolute general rule of full compensation in every case.” Schacter, “Compensation Cases-Leading and Misleading,” 79 Am. J. Int'l L. 420, 422 (1985). Given, however, that the Tribunal's immediate task is to decide the legal question of the standard of compensation existing as of 1955, it is not sufficient merely to state that in a practical sense the cases demonstrate “that foreign investors may get a fair award without asserting an absolute and inflexible rule.” Id. Nor can the Tribunal state that the rule is uncertain. See Lauterpacht, “Some Observations on the Prohibition of ‘Non-Liquet’ and the Completeness of Law,” reprinted in 2 H. Lauterpacht, Collected Papers 213 (1975).It is the duty of the Tribunal to decide the question using, inter alia, the above cases as evidence of customary law.

14 G.A. Res. 3171, 28 U.N. Gaor Supp. (No. 30) at 52, U.N. Doc. A/9030 (1973), reprinted in 13 Int'1 Legal Mat'Is 238 (1974).

15 G.A. Res. 3201, 28 U.N. Gaor Supp. (No. 1) at 3, U.N. Doc. A/9559 (1974), reprinted in 13 Int'l Legal Mat'Is 715 (1974).

16 G.A. Res. 3281, 29 U.N. Gaor Supp. (No. 31) at 50, U.N. Doc. A/9631 (1974), reprinted in 14 Int'1 Legal Mat'Is 252 (1975).’

17 See generally Schwebel, ‘The Legal Effect of Resolutions and Codes of Conduct of The United Nations,” 7 Forum Internationale (1985).

18 O Lissitzyn, International Law Today and Tomorrow 34-36 (1965).

19 See, e.g., de ArSchaga, “International Law in the Past Third of a Century,” 159 Recueil des Cours 1, 30-34 (1978); Akehurst, “Custom as a Source of International Law,” 47 Brit. Y.B. Int'l L. 1, 6-7 (1974-75); Bleicher, “The Legal Significance of Recitation of General Assembly Resolutions,” 63 Am. J. Int'l L. 444 (1969).

20 G.A. Res. 1803, 17 U.N. Gaor Supp.(No. 17) at 15, U.N. Doc. A/5344 (1962), reprinted in 57 Am. J. Int'1 L. 710 (1963)

21 Schwebel, “The Story of the U.N.'s Declaration on Permanent Sovereignty Over Natural Resources”, 49 Am.B.A.J. 463, 465-66 (1963).

22 See U.N. Doc. A/C.2/L. 1386 (1979) at 2.

23 Accord, Chilean Copper Case (L.G. Hamburg 1973), reprinted in 12 Int'1 Legal Mat'Is 251, 276 (1973).

24 Particularly significant in this regard, too, is the statement of the Iranian delegate in voting for Resolution 3281. The Iranian delegate noted the benefits of protecting foreign investment and stated that his vote in favor of the resolution was without prejudice to the international obligations Iran had assumed in that field, including those respecting compensation in the event of nationalization of foreign property. See Legal Problems of Multinational Corporations 148 (Simmonds ed. 1977) (citing AIC. 2/SR.1650 at 10-11).This statement is evidence that the Iranian Government did not view Resolution 3281 as affecting the meaning to be attributed to its obligations under the Treaty of Amity.

25 Sapphire International Petroleum Ltd. v. NIOC (Cavin arb.. Award of 15 Mar. 1963), reprinted in 35 Int'1 L. Rep. 136, 185-86.

26 BP Exploration Co. (Libya Ltd.) v. Government of the Libyan Arab Republic (Lagergren arb., Award of 1 Aug. 1974), reprinted in 53 Int'1 L. Rep. 297, 347.

27 H. Lauterpacht, Private Law Sources and Analogies of International Law 147 (1929).

28 Topco, supra, para. 105, 17 Int'1 Leg. Mat'Is at 35.

29 See, AGIP Co. v. Popular Republic of Congo, 30 paras. 88, 98 (Trolle, Dupuy & Rouhani arbs., ICSID Award of 30 Nov. 1979), reprinted in 21.Int'l Leg. Mat'Is 726, 737-38 (1982); Benvenuti et Bonfant v. People's Republic of the Congo, paras. 4.63-4.82 (Trolle, Bystricky & Razafindralambo arbs., ICSID Award of 8 Aug. 1980) (damages ex aeguo et bono include lost profits), reprinted in 21 Int'1 Leg. Mat'Is 740, 759-60 (1982); Amco Asia Corp. v. Republic of Indonesia, paras. 265-68 (Goldman, Foighel & Rubin arbs., ICSID Award of 20 Nov. 1984) , reprinted in 24 Int'l Legal Mat'Is 1022, 1036-37 (1985). But see Libyan American Oil Co. and Libyan Arab Republic (Mahmassani sole arb., Award of 12 Apr. 1977) ,- reprinted in 20 Int’ 1 Legal Mat’ Is 1 (1981).

30 See American International Group and Islamic Republic of Iran, Award No. 93-2-3 (19 Dec. 1983), reprinted in 4 Iran-g.S. C.T.R. 96 at 105 and 109 (“it is a general principle of public international law that even in a case of lawful nationalization the former owner of the nationalized property is normally entitled to compensation for the value of the property taken.“); Tippets, Abbett, McCarthy, Stratton and Islamic Republic of Iran, Award No. 141-7-2 at 10 (29 June 1984) (Claimant is entitled under international law and general principles of law to compensation for full value of the property of which it is deprived“). See also Concurring Opinion of George K. Aldrich (26 May 1983) to ITT Footnote Continued) Industries and Islamic Republic of Iran, Award No. 47-156-2 (26 May 1983) , reprinted in 2 Iran-q.S. C.T.R. 348.The reference to “normally” in American International Group presumably was intended to acknowledge that certain exceptional circumstances, e.g., war or similar exigency, might dictate a different result. As expressly noted, however, in the Restatement of the Law, Foreign Relations Law of the United States (Revised) (Council Draft No. 8, 7 Feb. 1986) §712, Comment d: A departure from the general rule on the ground of “exceptional circumstances” is unwarranted if (a) the property taken had been used in a business enterprise that was specifically authorized or encouraged by the state; or (b) the property was an enterprise taken for operation as a going concern by the state; or (c) the taking program did not apply equally to nationals of the taking state; or (d) the taking itself was otherwise wrongful [because not for a public purpose or because discriminatory]

31 I perceive no exception to this rule, whether under the Treaty of Amity or pursuant to customary international law, in the case of a programmatic nationalization, e.g., of an entire field of business. The Interdocutory Award addresses facts which Claimants assert constituted part of such a nationalization de facto, citing a meeting of the Iranian Board of Directors of Sediran in the fall of 1979 in which it was stated, regarding Iran's intention to form the National Iranian Drilling Company, that “all drilling activities in Iran will be taken over” and “there will be no job in Iran for Sediran.” Given Chairman Mangard's participation in American International Group and Islamic Republic of Iran, Award No. 93-2-3 (19 Dec. 1983), reprinted in 4 Iran-U.S. C.T.R. 96, which granted “going concern” value as “compensation for the value of the property taken” in what was described in the identical circumstances of INA Corporation, Award No. 184-161-1 (15 Sep. 1985) at 8, as “a classic example of a formal and systematic nationalisation by decree of an entire category of commercial enterprises considered of fundamental importance to the nation's economy,” and which the present Interlocutory Award cites with approval, no “nationalization exception” can be read into the Interlocutory Award. Any encouragement in that direction that might be drawn from the Separate Opinion of Judge Lagergren in INA Corporation and Islamic Republic of Iran, Award No. 184-161-1 (15 Sep. 1985), is, in my view, unjustified in light of the Award itself in that case and the thoughtful Separate Opinion of Judge Holtzmann. Likewise the fact that Claimant here, like the Claimant in-INA Corporation, has elected to measure the “full compensation” to which it is entitled by a method other than determining “going concern” value is of no consequence to the validity of the compensation standard itself.I perhaps should note, as is implicit in the Interlocutory Award's reference, at note 22, to interest and the “relevant principles of international law,” that full compensation, whether under the Treaty of Amity or customary international law, means not just an amount equivalent to the value of the property taken, but also the prompt payment of such amount, i.e., either at the time of taking or within a reasonable time thereafter with interest from the date of taking, in a form economically usable by the expropriated party (ordinarily convertible currency without restriction on repatriation).

32 See, e.g., Chilean Copper Case (L.G. Hamburg 1973), reprinted in 12 Int'l Legal Mat1Is 251, 276-77 (1973) (de facto discrimination found where the nationalization included only U.S.-owned mines and the nationalization consequently held to be illegal under international law) ; Seidl-Hohenveldern, “Chilean Copper Nationalization Cases Before German Courts,” 69 Am. J. Int'1 L. 110, 113 (1975).

33 See U.N. General Assembly Resolution 1803, supra; also Article IV(2) of the Treaty of Amity expressly prohibits such a taking.

34 Two additional grounds for unlawfulness occasionally cited are (1) denial of justice (see, e.g., Draft U.N. Code of Conduct for Transnational Corporations, Art. 52, reprinted in 1 Legal Problems of Codes of Conduct for Multinational Enterprises 502-503 (Horn ed., 1980)) and (2) failure promptly to pay the required compensation. I consider it unlikely that denial of justice in the customary sense constitutes a basis separate from those recognized above. For example, when the alleged denial of justice is lack of notice of the talcing or the lack of an opportunity to challenge judicially the propriety of the taking, the taking itself is not a damage resulting from the denial of justice. To the degree that the alien has a customary right to due process, the denial of justice does not render the previous taking unlawful, but rather is a wrong itself for which proximately caused damages may be sought. Although judicial review might have revealed discrimination or the lack of a public purpose, it is those aspects and not the lack of opportunity for municipal judicial review that render the taking unlawful. In some instances, the property protection provision of a bilateral investment treaty expressly requires, for example, prior notice of the proposed taking. In such situations, depending upon the wording of the provision, the lack of notice may render the taking itself unlawful or it may, as a breach of the treaty, constitute a separate unlawful act. Likewise I must express doubt as to whether, under customary international law, a State's mere failure, in the end, actually to have compensated in accordance with the international law standard set forth herein necessarily renders the underlying taking ipso facto wrongful. If, for example, contemporaneously with the taking the expropriating State provides a means for the determination of compensation which on its face appears calculated to result in the required compensation, but which ultimately does not, or if compensation is immediately paid which, though later found by a tribunal to fall short of the standard, was not on its face unreasonable, it would appear appropriate not to find that the taking itself was unlawful but rather only to conclude that the independent obligation to compensate has (Footnote Continued) not been satisfied. If, on the other hand, no provision for compensation is made contemporaneously with the taking, or one is made which clearly cannot produce the required compensation, or unreasonably insufficient compensation is paid at the time of ‘taking, it would seem appropriate to deem the taking itself wrongful. It is in such cases that restitutio in inteqrum may be appropriate as a remedy and that, in addition to that, or to a monetary award of damages, should that alternative be selected, a tribunal might consider an award of punitive damages. See note 35, infra.

35 See The Lusitania Cases, 7 Rep. Int'l Arb. Awards 32 (Parker umpire, Anderson & Kiesselbach comm., Opinion of 1 Nov. 1923) ; J. Ralston, International Arbitral Law and Procedure §3 6 9 (1910) (“While there is little doubt that in many cases the idea of punishment has influenced the amount of the award, yet we are not prepared to state that any commission has accepted the view that it possessed the power to grant anything save compensation.”) There are strong reasons in logic why it would be appropriate for an international tribunal to award punitive or exemplary damages against a State in such circumstances. In the absence of such damages being awarded against an unlawfully expropriating State, where restitution is impracticable or otherwise inadvisable, that State is required to furnish only the same full compensation as it would need to provide had it acted entirely lawfully. Thus, the injured party would receive nothing additional for the enhanced wrong done it and the offending State would experience no disincentive to repetition of unlawful conduct. If it is not deemed unseemly for the national courts of one State to “punish” at least certain entities of a foreign State, see U.S. Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, 28 U.S.C. §1606 (court award of punitive damages prohibited against a foreign state “except for an agency or instrumentality thereof,” defined in §1603(b) to include “a separate legal person … which is an organ of a foreign state”), it is questionable whether an international tribunal, particularly one formed by agreement of the only States Parties as to which it can adjudicate, need be so reticent.

36 Claimant has not argued strongly, however, either that the taking was not for a public purpose or that it was discriminatory.

37 It appears from the record before the Tribunal that Clause C was applied incorrectly to Sediran. The regulations implementing the Law for the Protection and Development Industries inter alia provide that Clause C shall be applied to factories and companies with substantial loans. By “substantial loan” is meant the sum total of two ratios: Long term loan divided by fixed assets before deducting amortization. Two times of the current debts divided by current assets in the balance sheet of the year 1356 (1977). Should the total of these two ratios be more than 2.5 such company shall be recognized as having a Only the second ratio is disputed by the Parties.I agree with Claimant that the sum of the two ratios equals 1.7 25 5 and that Clause C was therefore applied incorrectly. Such clear misapplication potentially opens to question the alleged public purpose underlying the taking. The lack of any provision for compensation having been made by Iran at any time also strongly implicates its responsibilities under both the Treaty of Amity and customary international law. By definition it is difficult to envision a de facto or “creeping” expropriation ever being lawful, for the absence of a declared intention to expropriate almost certainly implies that no contemporaneous provision for compensation has been made. Indeed, research reveals no international precedent finding such an expropriation to have been lawful.